Abstract

Benzodiazepines in intravenous sedation are useful, owing to their outstanding amnesic effect when used for oral surgery as well as dental treatments on patients with intellectual disability or dental phobia. However, compared with propofol, the effect of benzodiazepine lasts longer and may impede discharge, especially when it is administered orally because of fear of injections. Although flumazenil antagonizes the effects of benzodiazepine quickly, its effect on the equilibrium function (EF) has never been tested. Since EF is more objective than other tests, the purpose of this study is to assess the sedation level and EF using a computerized static posturographic platform. The collection of control values was followed by the injection of 0.075 mg/kg of midazolam. Thirty minutes later, 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg of flumazenil was administered, and the sedation level and EF were measured until 150 minutes after flumazenil administration. Flumazenil antagonized sedation, and there was no apparent resedation; however, it failed to antagonize the disturbance in EF. This finding may be due to differences in the difficulty of assessing the sedation level and performing the EF test, and a greater amount of flumazenil may effectively antagonize the disturbance in EF.

Keywords: Midazolam, Equilibrium function, Flumazenil, Reversal, Sedation

Sedation and general anesthesia are often used for oral surgery as well as dental treatments in patients with intellectual disability or dental phobia.1–3 In intravenous sedation, benzodiazepine injection is useful owing to its outstanding amnesic effect. Propofol has become a major anesthetic drug for intravenous sedation as well as general anesthesia in the last decade because of its short half-life. However, the amnesic effect of propofol is considered weaker than that of benzodiazepines, and vessel pain occurs when it is administered for induction. Thus, midazolam and propofol are used mainly for induction and maintenance, respectively, to alleviate these disadvantages. Although midazolam has the shortest half-life of benzodiazepine injections, its effects occasionally last longer than necessary. In addition, significant midazolam can be administered orally, if a patient cannot tolerate injections or inhale volatile anesthetics because of fear or lack of understanding. In this case, prolonging the effect of midazolam causes an unnecessary stay in the hospital or longer monitoring and care.

The residual effect of anesthetics has been evaluated by the investigator's subjective assessment, psychomotor tests, response to verbal commands, and so on. In clinical situations, the equilibrium function (EF) test, an established method to judge the recovery from anesthetics,4–6 is easier to apply and more objective compared with other tests. Flumazenil, a specific antagonist of benzodiazepines,7 acts by the competitive inhibition of binding these drugs to the central gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–benzodiazepine receptor complex, and reverses the sedative effects of benzodiazepines8,9; however, because of its relatively short β-elimination half-life compared with other benzodiazepines,10 resedation should be considered after treatment with flumazenil.11–13 At present, there has been no research on the effects of flumazenil against midazolam sedation using the EF test; therefore, the purpose of this study is to test EF objectively after the administration of midazolam and flumazenil using a computerized static posturographic platform, in addition to assessment of the sedative level. In addition, since resedation after flumazenil is considered to be induced due to the shorter duration of action of flumazenil compared with benzodiazepine remaining active, it raises the suggestion that a large amount of flumazenil may be effective in preventing resedation; therefore, we compared the effect of flumazenil 1.0 mg with flumazenil 0.5 mg in a double-blind manner.

Methods

Eight healthy male volunteers participated in this prospective, double-blind test. All participants were confirmed not to have histories of psychiatric illnesses or drug use. No subjects were taking any medications. The participants were instructed to refrain from coffee and solid food for 4 hours before the experiment. This study was approved by the ethical committee at Okayama University. The purpose of the study was explained to the subjects, and they gave written informed consent before participation. The median age of subjects was 25 (range 24 to 29) years, and their median weight was 60.5 (range 51 to 85) kg. All subjects were tested with both flumazenil 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg with an interval of at least 1 week. The allocation of the amounts of flumazenil was determined with a code sheet available to the anesthetist, but both the participant and the judge who assessed recovery were blind to the identity of the amount. All assessments were performed by one judge.

The sedation level was assessed on a 4-point scale as follows: 0 - awake and alert; 1 - drowsy; 2 - sedated, arousable when spoken to; 3 - sedated, not arousable. The EF test was made by using a computerized static posturographic platform (Gravicorder GS10, Anima, Tokyo Japan), which can record the extent of movement of the body's center of gravity (CG). Subjects stood on the platform in the heel position with feet spread at an angle of approximately 30° and with eyes open for 1 minute. The area of CG was automatically calculated by the platform (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gravicorder GS10. As shown in this picture, subjects stood on the platform in the heel position with feet spread at an angle of approximately 30°.

After obtaining control results, a suitable vein was cannulated and midazolam, 0.075 mg/kg, was administered intravenously. Thirty minutes later the test drug (flumazenil 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg) was administered intravenously. The subjects were assessed for their sedation level before the test drug, and at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes after the administration of the test drug. After each assessment of the sedation level, subjects were tested with the force platform at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes after the drug. The EF test was not performed just before the injection of flumazenil because it was difficult for the participants to continue standing for 1 minute on the platform in a preliminary test.

The results within groups were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttests. And, for comparisons between groups, 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni posttests were used. A P value <.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

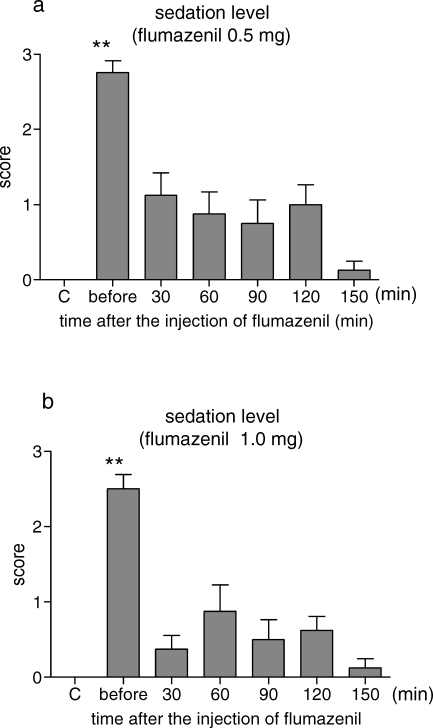

Sedation Level

Just before the injection of 0.5 mg of flumazenil, all of the cases were judged as a score of 2 or 3. The values were significantly higher than those of the control. After the administration of flumazenil, the sedation levels were clearly improved. The sedation scores were kept low without significance compared with the control, although some of the cases were judged as a score of 1 or 2 (Figure 2a). The changes in the sedation level after 1.0 mg of flumazenil were similar to those after 0.5 mg of flumazenil. The sedation scores were decreased after the injection of 1.0 mg of flumazenil (Figure 2b). There was no significant difference between groups.

Figure 2.

Changes in the sedation level. The results are expressed as the mean ± SE (n = 8). Midazolam 0.075 mg/kg was administered intravenously, and 30 minutes later, the test drug (flumazenil 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg) was administered. The sedation level was assessed on a 4-point scale as follows: 0 - awake and alert; 1 - drowsy; 2 - sedated, arousable when spoken to; 3 - sedated, not arousable. (a) Effects of 0.5 mg of flumazenil. (b) Effects of 1.0 mg of flumazenil. C indicates control; before, before an injection of flumazenil. ** Significantly different from the control values, P < .01.

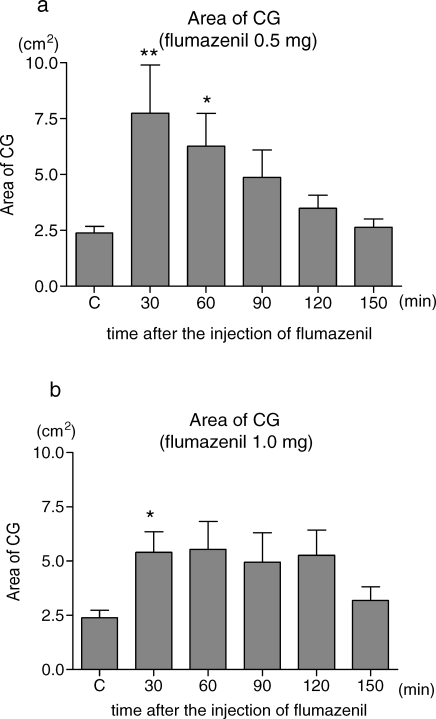

Equilibrium Function Tests

The EF test showed different results from that of the sedation level. The area of CG was significantly larger than the control values after the injection of flumazenil. The injection of 0.5 mg flumazenil was not able to antagonize the effect of midazolam, and the values were significantly higher than the control 30 and 60 minutes after the flumazenil injection. But there was no significant difference 90, 120, and 150 minutes after the flumazenil injection (Figure 3a). After the administration of 1.0 mg of flumazenil, the EF was significantly disturbed 30 minutes after the flumazenil injection. Sixty, 90, and 120 minutes after the flumazenil injection, the mean values of the area of CG were higher than those of the control, although there was no significance (Figure 3b). There was no significant difference between groups.

Figure 3.

Changes in the area of CG (center of gravity). The results are expressed as the mean ± SE (n = 8). Measurement of the area of CG was performed just after the assessment of the sedation level. Subjects stood on the platform with their eyes open for 1 minute. The values were automatically calculated by the platform. (a) Effects of 0.5 mg of flumazenil. (b) Effects of 1.0 mg of flumazenil. C indicates control; before an injection of flumazenil. * Significantly different from the control values, P < .05, ** P < .01.

Discussion

Both amounts of flumazenil antagonized the hypnotic effects of midazolam after the administration, and the recovery patterns in the sedation level were quite similar to each other. Additionally, resedation was not observed in both groups within the time of observation. On the other hand, the EF remained disturbed after the administration of flumazenil in both groups, especially after a lower dose of flumazenil. Thus, although the hypnotic effect of midazolam was antagonized without resedation by flumazenil of both amounts, the disturbance of the EF after the flumazenil injection did not recover. In previous reports, resedation was not observed when the sedation level was assessed by the investigator's subjective assessment.14,15 However, in psychomotor tests, impairments were observed even 3 hours after the administration of flumazenil.16,17 It was also reported that standing independently was more sensitive than both spontaneous eye opening and response to a verbal command.18 Therefore, the difference in sensitivity may lead to a gap in the recovery pattern between the assessment of the sedation level and the EF test.

Another possible mechanism of the gap was the specific selectivity in receptor binding of flumazenil. The affinities of 21 kinds of benzodiazepines to the glycine receptor were demonstrated to vary widely, and the effects of muscle relaxation by benzodiazepines are highly correlated with the affinity to the glycine receptor.19,20 Since the muscle relaxant by benzodiazepine is considered to mainly be mediated by the glycine receptor,20,21 it is possible that midazolam disturbs the EF partly via the glycine receptor, at which flumazenil does not antagonize with high affinity. Psychomotor tests have been used also to judge the recovery from anesthetics. Among them, only the critical flicker fusion threshold did not show a significant antagonistic effect of flumazenil.16,22 This raises a possibility that the effects of flumazenil may be specific to a part of the effect of benzodiazepines in psychomotor tests as well.

The benzodiazepine receptor is divided into 2 types. One is the central type benzodiazepine receptor (CBR), which is located in neurons and coupled with GABA receptors.23 The other is called the peripheral type benzodiazepine receptor (PBR), which is localized in the CNS and most peripheral organs.24 Midazolam binds to both the CBR and the PBR, while flumazenil binds specifically to the CBR.25,26 Therefore, flumazenil is considered not to antagonize the effect of midazolam to the PBR. This difference in binding to the PBR may be partly related to the disturbance of the EF after flumazenil injection. However, since there is no research on the relationship between the PBR and the EF, further study is necessary to describe it in detail.

From a clinical point of view, although they are fully awake, patients given flumazenil against light sedation should be warned as to their decision of leaving the hospital because of the prolonged disturbance to their EF, even after 1.0 mg of flumazenil. In addition, since 1.0 mg of flumazenil was comparatively more effective in this study, a greater amount of flumazenil may be able to work more effectively against the disturbance of the EF caused by midazolam. However, the number of participants in this study is limited, and individual β-elimination of half-life is reported to vary widely even in healthy volunteers.10 Therefore, in order to evaluate precise clinical pharmacological effect of flumazenil, there will be a future study with a greater sample size to assess the effects of flumazenil upon EF that stratifies the population in terms of age, sex, weight, or other criteria.

Conclusion

Following 0.075 mg/kg midazolam intravenous sedation, both 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg doses of flumazenil antagonized the level of sedation after 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes with no evidence of re-sedation. However, the 0.5 dose of flumazenil failed to reverse the disturbance of EF at 30 and 60 minutes. The 1.0 mg dose of flumazenil failed to reverse the disturbance of EF at 30 minutes.

References

- Dionne R.A, Yagiela J.A, Moore P.A, Gonty A, Zuniga J, Beirne O.R. Comparing efficacy and safety of four intravenous sedation regimens in dental outpatients. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:740–751. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki T, Kohjitani A, Maeda S, et al. Intravenous sedation for dental patients with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2004;48:764–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korttila K. Clinical effectiveness and untoward effects of new agents and techniques used in intravenous sedation. J Dent Res. 1984;63:848–852. doi: 10.1177/00220345840630060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Ledin T, Larsen L.E, Lennmarken C, Odkvist L.M. Computerized dynamic posturography: a new method for the evaluation of postural stability following anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1991;66:667–672. doi: 10.1093/bja/66.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledin T, Gupta A, Larsen L.E, Odkvist L.M. Randomized perturbed posturography: methodology and effects of midazolam sedation. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;113:245–248. doi: 10.3109/00016489309135801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korttila K, Ghoneim M.M, Jacobs L, Lakes R.S. Evaluation of instrumented force platform as a test to measure residual effects of anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 1981;55:625–630. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198155060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunkeler W, Mohler H, Pieri L, et al. Selective antagonists of benzodiazepines. Nature. 1981;290:514–516. doi: 10.1038/290514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H, Richards J.G. Agonist and antagonist benzodiazepine receptor interaction in vitro. Nature. 1981;294:763–765. doi: 10.1038/294763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauven P.M, Schwilden H, Stoeckel H, Greenblatt D.J. The effects of a benzodiazepine antagonist Ro 15-1788 in the presence of stable concentrations of midazolam. Anesthesiology. 1985;63:61–64. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198507000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short T.G, Young K.K, Tan P, Tam Y.H, Gin T, Oh T.E. Midazolam and flumazenil pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics following simultaneous administration to human volunteers. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1994;38:350–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1994.tb03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghouri A.F, Ruiz M.A, White P.F. Effect of flumazenil on recovery after midazolam and propofol sedation. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:333–339. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199408000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausen N.O, Juhl O, Sorensen J, Ferguson A.H, Neumann P.B. Flumazenil in total intravenous anaesthesia using midazolam and fentanyl. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1988;32:409–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1988.tb02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger T.J, Morawetz R.F, Mitterschiffthaler G. Additional subcutaneous administration of flumazenil does not shorten recovery time after midazolam. Br J Anaesth. 1990;64:53–58. doi: 10.1093/bja/64.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S, Knudsen L, Kirkegaard L, Kruse A, Knudsen E.B. Flumazenil used for antagonizing the central effects of midazolam and diazepam in outpatients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1989;33:26–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1989.tb02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson M.S, Skeie B, Emhjellen S, Wickstrom E, Steen P.A. Antagonism of diazepam-induced sedative effects by Ro15-1788 in patients after surgery under lumbar epidural block. A double-blind placebo-controlled investigation of efficacy and safety. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1987;31:629–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1987.tb02634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews P.J, Wright D.J, Lamont M.C. Flumazenil in the outpatient. A study following midazolam as sedation for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Anaesthesia. 1990;45:445–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1990.tb14330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders L.D, Piggott S.E, Isaac P.A, et al. Reversal of benzodiazepine sedation with the antagonist flumazenil. Br J Anaesth. 1991;66:445–453. doi: 10.1093/bja/66.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratila M.G, Fischer M.E, Alagesan R, Reinsel R.A, Pratilas D. Propofol versus midazolam for monitored sedation: a comparison of intraoperative and recovery parameters. J Clin Anesth. 1993;5:268–274. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(93)90117-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder S.H, Enna S.J, Young A.B. Brain mechanisms associated with therapeutic actions of benzodiazepines: focus on neurotransmitters. Am J Psychiatry. 1977;134:662–665. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.6.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A.B, Zukin S.R, Snyder S.H. Interaction of benzodiazepines with central nervous glycine receptors: possible mechanism of action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:2246–2250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.6.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter J.J. Current theories about the mechanisms of benzodiazepines and neuroleptic drugs. Anesthesiology. 1981;54:66–72. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J.C. Flumazenil reverses a paradoxical reaction to intravenous midazolam in a child with uneventful prior exposure to midazolam. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:369–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield P.R, Darlison M.G, Fujita N, et al. Sequence and functional expression of the GABA A receptor shows a ligand-gated receptor super-family. Nature. 1987;328:221–227. doi: 10.1038/328221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braestrup C, Squires R.F. Specific benzodiazepine receptors in rat brain characterized by high-affinity (3H)diazepam binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:3805–3809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reves J.G, Fragen R.J, Vinik H.R, Greenblatt D.J. Midazolam: pharmacology and uses. Anesthesiology. 1985;62:310–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak J.C, Barnes P.J. Peripheral type benzodiazepine receptors in human and guinea pig lung: characterization and autoradiographic mapping. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;252:880–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]