Abstract

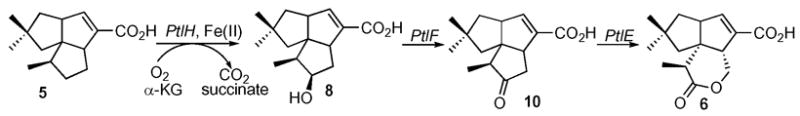

The hydroxylase encoded by theptlH (SAV2991) gene from the pentalenolactone gene cluster ofStreptomyces avermitilis was cloned by PCR and expressed inEscherichia colias an N-terminal-His6-tag protein. Incubation of recombinant PtlH with (±)-1- deoxypentalenic acid (5) in the presence of Fe(II), α-ketoglutarate, and O2 gave (−)-11β-hydroxy-1-deoxypentalenic acid (8), whose structure and stereochemistry were determined by a combination of1H,13C, COSY, HMQC, HMBC, and NOESY NMR. The steady state kinetic parameters werekcat 4.2±0.6 s−1 andKm (5) 0.57±0.19 mM.8 is a new intermediate in the conversion of the sesquiterpene pentalenene (3) to pentalenolactone (1).

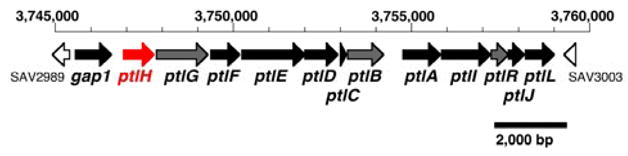

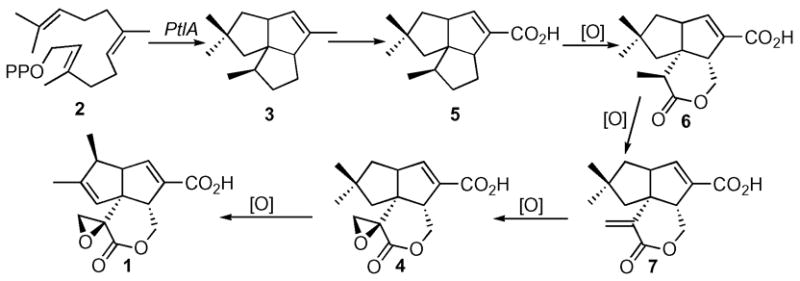

Streptomyces avermitilis is a Gram-positive soil organism that is responsible for the production of the widely used anthelminthic macrolide avermectins. (S. avermectinius is a junior homotypic synonym of S. avermitilis.) The 9.03 Mb linear chromosome harbors 7,575 open reading frames (ORFs), including some 30 gene clusters thought to be related to secondary metabolism, corresponding to 7% of the genome.1 We have recently reported the molecular genetic and biochemical identification of the gene cluster for the biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene antibiotic pentalenolactone (1), in a 13.4-kb segment centered at 3.75 Mb in the S. avermitilis genome that contains 13 unidirectionally-transcribed ORFs (Figure 1).2 Among these ORFs, the 1011-bp ptlA (SAV2998), encodes pentalenene synthase, a protein of 336 amino acids that catalyzes the cyclization of farnesyl diphosphate (2) to pentalenene (3), the established parent hydrocarbon of the pentalenolactone family of antibiotics (Scheme 1).2,3 The gap1 (SAV2990) gene, which encodes a pentalenolactone-insensitive glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, corresponds to the pentalenolactone resistance gene.2,4 A typical farnesyl diphosphate synthase is apparently encoded by ptlB, while ptlR and ptlG have been assigned as a putative transcriptional regulator and a transmembrane efflux protein, respectively. All of the remaining 8 ORFs correspond to redox enzymes, among which is a cytochrome p450 (CYP183A1, ptlI),5 a dehydrogenase (ptlF), and six monooxygenases and dioxygenases.

Figure 1.

Pentalenolactone biosynthetic gene cluster from S. avermitilis. See the website of the S. avermitilis Genome Project http://avermitilis.ls.kitasato-u.ac.jp/ for annotations and detailed sequence alignments.

Scheme 1.

Several presumptive intermediates as well as a number of shunt metabolites in the conversion of pentalenene to pentalenolactone have been isolated from cultures of a wide variety of pentalenolactone-producing Streptomyces species.6 Pentalenolactone F (4), has also recently been isolated from S. avermitilis,2 confirming that the pentalenolactone pathway is functional in this organism. Along with 1-deoxypentalenic acid (5),6a pentalenolactone D (6),6g and pentalenolactone E (7),6e these metabolites can be organized into a plausible biosynthetic pathway (Scheme 1). Beyond the conversion of labeled pentalenene (3) to pentalenolactone (1),3b these proposed biosynthetic relationships have yet to be demonstrated experimentally, and none of the enzymes linking pentalenene (3) to pentalenolactone (1) have been identified. We report below the biochemical characterization of PtlH (SAV2991), a non-heme iron, α-ketoglutate dependent hydroxylase that catalyzes the conversion of 1-deoxypentalenic acid (5) to a new biosynthetic intermediate, 11β-hydroxy-1-deoxypentalenic acid (8).

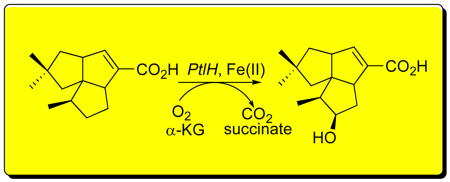

BLAST searching indicates that ptlH has 26% amino acid sequence identity and 44% similarity over 244 residues to phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (PhyH, Genbank Accession No. YP_086787). PhyH, which catalyzes the α-hydroxylation of phytanoyl-CoA, belongs to the sub-family of Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylases.7 We therefore hypothesized that PtlH might be responsible for hydroxylation of the methylcyclopentane ring of 1-deoxypentalenic acid (5) in the oxidative conversion of 5 to pentalenolactone D (6) (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

PtlH was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from DNA of S. avermitilis cosmid CL_216_D07 and cloned into the vector pET28e. The resulting construct pET28e-PtlH was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). After induction with IPTG, the expressed PtlH protein, carrying an N-terminal His6-tag, was purified to homogeneity by Ni-NTA chromatography. The purified protein had a subunit MD by MALDI-TOF MS of m/z 37139±19 (calc. 37121). The presence of a second peak at m/z 73965 suggested that PtlH may be a homodimer.

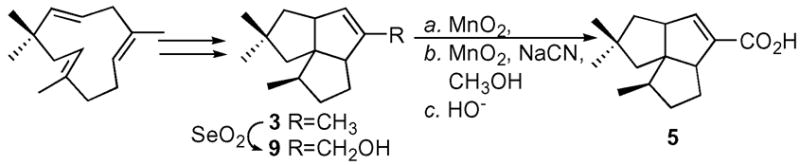

The requisite substrate (±)-1-deoxypentalenic acid (5) was synthesized from α-humulene by way of (±)-pentalenene (3) and (±)-pentalen-13-ol (9), as previously described (Scheme 3).8 A mixture (1.5 mL) of recombinant PtlH (1.66 μM), α-ketoglutarate (2 mM), L-ascorbic acid (2 mM), FeSO4 (1 mM), DTT (1.5 mM), and bovine catalase (1 mg/mL) in 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.3) was incubated with (±)-(5) (0.64 mM) overnight at room temperature. After acidification with HCl, the mixture was extracted with diethyl ether and the organic extract was treated with TMS-CHN2 to generate the methyl ester. GC-MS analysis (HP5ms, 30 m × 0.25 mm) revealed a single new peak with m/z 264, indicating the formation of the hydroxylated product. Chiral GC-MS analysis (Hydrodex-β-6-TBDM, 25 m × 0.25 mm), under conditions in which the methyl esters of (±)-deoxypentalenic acid were well resolved. confirmed that the enzymatic reaction product was a single enantiomer. Control incubations that omitted α-ketoglutarate or Fe(II) showed no turnover of 5. Neither (±)-pentalenene (3) (0.5 mM) nor (±)-pentalen-13-ol (9) (0.1 mM) underwent PtlH-catalyzed hydroxylation.

Scheme 3.

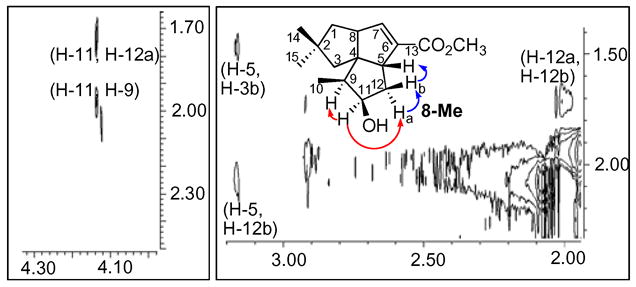

A preparative-scale incubation was carried out with PtlH and 1-deoxypentalenic acid (5). The isolated product was converted to the methyl ester 8-Me, which was purified by preparative TLC and analyzed by 1H, 13C, COSY, HMQC, HMBC, and NOESY NMR as well as EI-MS.9 In the 13C NMR spectrum of 8-Me the C-11 methylene of 5 was replaced by a new methine signal at 76.0 ppm that was correlated with the H-11 carbinyl proton signal at δ 4.10 (m), consistent with the introduction of the hydroxyl group at C-11. This assignment was corroborated by the HMBC spectrum, which exhibited the expected cross peak between C-11 and the H-10 methyl protons at δ 0.99 (d, J=7 Hz, 3H). The configuration of the 11β-hydroxyl group of 8-Me was readily established by the NOESY spectrum, which showed correlations between H-11 and both H-9 (δ 1.92) and H-12a (δ 1.72) as well as between H-12b (δ 2.05) and H-12a and H-5 (δ 3.19) (Figure 2).10

Figure 2.

Details of NOESY spectrum of methyl (−)-11β-hydroxy-1-deoxypentalenate (8-Me).

PtlH showed a pH optimum of 6.0. The steady-state kinetic parameters were determined by carrying out a series of 30-min incubations with 0.097 – 0.97 mM (±)-1-deoxypentalenic acid (5) and quantitation of the product 8-Me by calibrated GC-MS. Fitting of the initial velocities to the Michaelis-Menten equation gave kcat 4.2±0.6 s−1 and a Km (5) of 0.57±0.19 mM.

These results firmly establish the biochemical function of the ptlH gene product, which is shown to catalyze the Fe(II)- and α-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylation of 5 to 11β-hydroxy-1-deoxypentalenic acid (8) (Scheme 2). Further conversion of 5 to pentalenolactone D (6) may involve oxidation of 5 to the ketone 10 by PtlF, an apparent NAD+-dependent dehydrogenase, followed by Baeyer-Villiger-like oxidaton of 10 mediated by PtlE, which has 49% identity and 62% similarity over 591 aa to the cyclodecanone–lauryl lactone dioxygenase of Rhodococcus ruber (Genbank AY052630.1).

Supplementary Material

Expression of recombinant PtlH, spectroscopic data for 8-Me, and kinetic assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. See any current masthead page for ordering information and Web access instructions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Russell Hopson for assistance with the NMR experiments and Dr. Tun-Li Shen for obtaining the mass spectra. This work was supported by NIH grant GM30301 to DEC, by Grant of the 21st Century COE Program, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan to H.I and S.O, and by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science No. 17510168 to H.I

References and Notes

- 1.Omura S, Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, Hanamoto A, Takahashi C, Shinose M, Takahashi Y, Horikawa H, Nakazawa H, Osonoe T, Kikuchi H, Shiba T, Sakaki Y, Hattori M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12215–12220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211433198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, Hanamoto A, Shinose M, Kikuchi H, Shiba T, Sakaki Y, Hattori M, Omura S. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:526–531. doi: 10.1038/nbt820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tetzlaff CN, You Z, Cane DE, Takamatsu S, Omura S, Ikeda H. Biochemistry. 2006 doi: 10.1021/bi060419n. submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Cane DE, Sohng JK, Lamberson CR, Rudnicki SM, Wu Z, Lloyd MD, Oliver JS, Hubbard BR. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5846–5857. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cane DE, Oliver JS, Harrison PHM, Abell C, Hubbard BR, Kane CT, Lattman R. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4513–4524. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Frohlich KU, Kannwischer R, Rudiger M, Mecke D. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:179–186. doi: 10.1007/BF01692859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cane DE, Sohng JK. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;270:50–61. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamb DC, Ikeda H, Nelson DR, Ishikawa J, Skaug T, Jackson C, Omura S, Waterman MR, Kelly SL. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307:610–619. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) 5 has been isolated as the glucuronate ester: Takahashi S, Takeuchi M, Arai M, Seto H, Otake N. J Antibiot. 1983;36:226–228. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.226.Seto H, Yonehara H. J Antibiot. 1980;33:92–93. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.92.Seto H, Sasaki T, Uzawa J, Takeuchi S, Yonehara H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978:4411–4412.Seto H, Sasaki T, Yonehara H, Uzawa J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978:923–926.Cane DE, Rossi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979:2973–2974.Williard PG, Sohng JK, Cane DE. J Antibiot. 1988;41:130–133. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.130.Cane DE, Sohng JK, Williard PG. J Org Chem. 1992;57:844–851.

- 7.Mihalik SJ, Rainville AM, Watkins PA. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:545–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.545zz.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Ohfune Y, Shirahama H, Matsumoto T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976:2869–2872. [Google Scholar]; b) Ohtsuka T, Shirahama H, Matsumoto T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:3851–3854. [Google Scholar]; c) Cane DE, Tillman AM. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:122–124. [Google Scholar]; Tillman AM. PhD Thesis. Brown University; Providence, RI: 1984. pp. 60–115. [Google Scholar]

- 9.8-Me: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.66 (1H, H-7, m); 4.10 (1H, H-11, m); 3.74 (3H, OCH3, s); 3.19 (1H, H-5, m); 2.93 (1H, H-8, m); 2.05 (1H, H-12, m); 1.92 (2H, H-3, d, J=13.5 Hz, H-9, m);1.72 (2H, H-1, H-12, m); 1.45 (1H, H-3, d, J=13.5 Hz); 1.31(1H, H-1, dd, J=5.26, 12.78 Hz); 1.02 (3H, H-14 or H-15). 13C NMR 75.47 MHz, CDCl3) 166.0 (C-13); 147.9 (C-7); 137.7 (C-6); 76.0 (C-11); 62.8 (C-4); 59.5 (C-8); 55.9 (C-5); 51.8 (OCH3); 50.2 (C-3); 48.5 (C-9); 45.7 (C-1), 41.26 (C-2); 38.4 (C-12), 30.2 (C-14 or C-15); 29.5 (C-14 or C-15); 10.6 ppm (C-10). δD22 = −10.5° (CH2Cl2, c=0.1 g/100 mL). HRMS 264.1718; calc. C16H22O3: 264.1725.

- 10.The 11α-hydroxyl epimer of 8-Me has a signal for H-11 at δ 370 (ref 8b).

- 11.Kinetic assays were carried at 23 °C with PtlH (0.093 μM) in MES (95 mM, pH 6.0) containing α-ketoglutarate (2.67 mM), L-ascorbate (2.67 mM), FeSO4 (1.33 mM), catalase (0.95 mg/mL), DTT (1 mM) in a total vol. of 200 μL. Reactions were initiated by adding a solution of (±)-deoxypentalenic acid (5) in DMSO to a concentration of 0.097 - 0.97 mM (final DMSO conc. 4%). The reactions were quenched with HCl at 30 min, and the mixtures were extracted with ether, treated with TMS-CHN2 and analyzed by GC-MS.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression of recombinant PtlH, spectroscopic data for 8-Me, and kinetic assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. See any current masthead page for ordering information and Web access instructions.