Abstract

TSG-6 is an inflammation-induced protein that is produced at pathological sites, including arthritic joints. In animal models of arthritis, TSG-6 protects against joint damage; this has been attributed to its inhibitory effects on neutrophil migration and plasmin activity. Here we investigated whether TSG-6 can directly influence bone erosion. Our data reveal that TSG-6 inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation/activation from human and murine precursor cells, where elevated dentine erosion by osteoclasts derived from TSG-6-/- mice is consistent with the very severe arthritis seen in these animals. However, the long bones from unchallenged TSG-6-/- mice were found to have higher trabecular mass than controls, suggesting that in the absence of inflammation TSG-6 has a role in bone homeostasis; we have detected expression of the TSG-6 protein in the bone marrow of unchallenged wild type mice. Furthermore, we have observed that TSG-6 can inhibit bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2)-mediated osteoblast differentiation. Interaction analysis revealed that TSG-6 binds directly to RANKL and to BMP-2 (as well as other osteogenic BMPs but not BMP-3) via composite surfaces involving its Link and CUB modules. Consistent with this, the full-length protein is required for maximal inhibition of osteoblast differentiation and osteoclast activation, although the isolated Link module retains significant activity in the latter case. We hypothesize that TSG-6 has dual roles in bone remodeling; one protective, where it inhibits RANKL-induced bone erosion in inflammatory diseases such as arthritis, and the other homeostatic, where its interactions with BMP-2 and RANKL help to balance mineralization by osteoblasts and bone resorption by osteoclasts.

TSG-6,4 the ∼35-kDa secreted product of TNF-stimulated gene-6 (1), is expressed in response to various inflammatory mediators and growth factors (2). It is comprised almost entirely of contiguous Link and CUB modules and binds to a diversity of protein and glycosaminoglycan ligands, including pentraxin-3, thrombospondin-1, thrombospondin-2, aggrecan, versican, inter-α-inhibitor, bikunin, bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2), fibronectin, hyaluronan (HA), heparin, heparan sulfate, chondroitin 4-sulfate, and dermatan sulfate (1, 3–16). The three-dimensional structure of the Link module from human TSG-6 (produced in Escherichia coli and termed Link_TSG6 (17)) has been determined by both NMR spectroscopy and x-ray crystallography (13, 14, 18), where the ligand binding sites for HA, bikunin, and heparin have been mapped onto this domain (8, 19, 20). In addition, we have recently expressed the CUB_C domain from human TSG-6 (termed CUB_C_TSG6 (12)), which comprises the CUB module and C-terminal region of the protein, and have used this material to obtain an x-ray structure for the TSG-6 CUB module.5

Current data suggest that TSG-6 is not constitutively expressed in normal adult tissues, but rather that it is associated with inflammatory diseases (2, 21, 22) such as asthma (23) and arthritis (24, 25). However, TSG-6 is produced in ovulating ovarian follicles, where it has an essential physiological role in female fertility (26, 27). TSG-6 has been most extensively studied in the context of articular joint disease; it has been detected in the synovial fluid, cartilage, and synovia of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients but not in the corresponding normal tissues (24, 25). It is likely that TSG-6 is produced locally at disease lesions in joints, as its expression can be induced in cultured human chondrocytes by TNF, IL-1, IL-6, TGF-β, and platelet-derived growth factor (28, 29), and it is constitutively expressed by synoviocytes from RA patients, where its production is further enhanced by treatment with IL-1, TNF (24), and IL-17 (30). A number of studies have revealed that TSG-6 has a protective role in experimental models of arthritis (31–35). For example, in collagen-induced arthritis (an autoimmune polyarthritis with a histopathology similar to human RA) there was delayed onset of symptoms and reduction of both disease incidence and joint inflammation/destruction in TSG-6 transgenic mice or wild type mice treated systemically with recombinant human TSG-6 (31, 32), where the TSG-6 transgene mediated an effect comparable with anti-TNF antibody treatment in mice (32). In cartilage-specific TSG-6 transgenic mice, the instigation of antigen-induced arthritis (a model of monoarticular arthritis) resulted in delayed cartilage damage compared with controls, with reduced degradation of aggrecan by matrix metalloproteinases and aggrecanases (34). Furthermore, there was evidence of cartilage regeneration 4–5 weeks after the onset of disease in these animals. Similar chondroprotective effects were seen in wild type mice where recombinant murine TSG-6 was injected directly into the affected joint in antigen-induced arthritis or intravenously in proteoglycan-induced arthritis (a model of human RA) (33). The anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective effects of TSG-6 observed in these studies are likely to be due to more than one mechanism (22). For example, TSG-6 is a potent inhibitor of neutrophil extravasation in vivo (36–38) and has also been implicated in the inhibition of the protease network through its potentiation of the anti-plasmin activity of inter-α-inhibitor (8, 36, 37), where plasmin is a key regulator of proteolysis during inflammation, e.g. via its activation of matrix metalloproteinases. In this regard, TSG-6-/- mice develop an accelerated and much more severe form of proteoglycan-induced arthritis than controls, having extensive cartilage degradation and bone erosion, which was attributed to increased neutrophil infiltration and plasmin activity in the inflamed paw joints (35).

The data presented here demonstrate that TSG-6 inhibits bone erosion by osteoclasts and that this is likely to be mediated via a mechanism that involves its direct interaction with RANKL (the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand), the major regulator of osteoclast activity and of joint destruction in arthritis. We have also shown that TSG-6 binds to osteogenic bone morphogenetic proteins (i.e. BMP-2, -4, -5, -6, -7, -13, and -14) and provide evidence that TSG-6 has a physiological role in bone homeostasis via the regulation of both bone formation and resorption.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Recombinant TSG-6 Proteins—Full-length recombinant human (rh)TSG-6 was expressed in Drosophila S2 cells and purified as described previously (39). Link_TSG6 (the Link module of human TSG-6, corresponding to residues 36–133 of the pre-protein (1)) and CUB_C_TSG6 (the CUB domain and C-terminal 27 amino acids; i.e. residues 129–277 of the human pre-protein) were expressed in E. coli, purified, and characterized as described in Day et al. (17), Kahmann et al. (40), and in Kuznetsova et al. (12), respectively.

Effect of TSG-6 on RANKL-induced Human Osteoclast Formation—To determine the effects of TSG-6 on RANKL-induced human osteoclast formation, human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy male volunteers (age range 25–35 years) as described in Sabokbar and Athanasou (41). Briefly, blood was collected in EDTA-treated tubes and diluted 1:1 in α-minimum essential medium (αMEM) (Invitrogen), layered over Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich), then centrifuged (693 × g), washed, and resuspended in αMEM with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Invitrogen). PBMCs were counted after lysis of red cells with 5% (v/v) acetic acid and seeded (at 5 × 105 cells/well) into 96-well tissue culture plates containing either dentine slices or coverslips. After 2 h of incubation, dentine slices and coverslips were removed from the wells and washed vigorously in αMEM to remove non-adherent cells before transfer into 24-well tissue culture plates containing 1 ml/well αMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 10 mm l-glutamine, antibiotics (100 IU/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml streptomycin), 25 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; R&D Systems Europe), and 50 ng/ml soluble (s)RANKL (PeproTech). After the addition of rhTSG-6 (30.1 kDa (39)) at 0–50 ng/ml or equimolar concentrations of Link_TSG6 (10.9 kDa (17)) or CUB_C_TSG6 (16.8 kDa (12)), cultures were maintained for up to 21 days, during which time the entire culture medium containing all factors was replenished every 2–3 days.

Osteoclast formation was assessed cytochemically by determining the number of multinucleated tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive cells after 14 days in culture. Cells on coverslips were fixed in 10% (v/v) formalin and stained using napthol AS-BI as a substrate in the presence of 1.0 m acetate-tartrate; the reaction was stopped with 0.5 m NaF. Bone resorptive activity, an indicator of osteoclast activation, was determined by the measurement of resorption lacunae on dentine slices. After 21 days in culture dentine slices were removed from the wells, rinsed in PBS, placed in 1.0 m NH4OH overnight, and then sonicated for 5–10 min; this resulted in complete removal of cells from the dentine slice, permitting examination of its surface. The slices were washed in distilled water, stained with 0.5% (w/v) aqueous toluidine blue, pH 5.0, and examined by light microscopy. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase staining was analyzed using ImageJ software (rsb.info.nih.gov/ij), whereas for lacunar resorption the data were expressed as the mean percentage area resorbed from four dentine slices per treatment. Each set of experiments was repeated at least three times.

Extent of Osteoclast Formation in TSG-6-deficient Mice—TSG-6-/- mice were generated as described previously (27) and back-crossed into the BALB/c background (35). Age-matched pairs of female TSG-6-/- and wild type (WT) BALB/c mice (between 18 and 25 weeks of age) were used for experiments. All procedures carried out on animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL). Bone marrow cells from the long bones of TSG-6-/- mice were isolated as previously described (42). Briefly, mice were killed by CO2 inhalation, and the femora and tibiae were aseptically removed and dissected free of adherent soft tissue. The bone ends were cut, and the marrow cavity was flushed out into a Petri dish by slowly injecting αMEM at one end of the bone using a sterile 21-gauge needle. The bone marrow suspension was carefully agitated with a plastic Pasteur pipette to obtain a homogeneous suspension of cells, and these were incubated for 2 h at a density of 5 × 104 cells/ml in 96-well plates containing dentine slices. Non-adherent cells were removed from the dentine slices (by vigorous washing in αMEM), which were then transferred to 24-well plates containing αMEM with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated serum and antibiotics (as described above). Cultures on dentine slices were maintained in the presence of 25 ng/ml M-CSF (R&D Systems Europe) and 30 ng/ml murine sRANKL (PeproTech) for 10 days during which the culture media and factors were replenished every 2–3 days. The extent of lacunar resorption was then determined as described above.

Micro-computerized Tomography (CT) Analysis of Long Bones from TSG-6-deficient and WT Mice—Micro-CT analysis of the long bones in TSG-6-deficient and WT mouse femurs was performed to determine any differences in trabecular bone; four pairs of age-matched male mice (24–28 weeks) were analyzed. Briefly, plastic-wrapped knees were mounted vertically on a Skyscan 1172 micro-CT scanner and scans (6.77 μm with a voxel resolution of 6.9 μm2) were performed using a 20–100-kV microfocus x-ray source with a 10-megapixel digital x-ray camera. The images obtained were subjected to three-dimensional angular resampling (using Skyscan 3D-creator software), and morphometric parameters were calculated for trabecular regions of interest using a Marching Cubes model (43) as described previously (44).

Immunolocalization of TSG-6 in the Mouse Knee Joint—Mouse knee joints were prepared for confocal immunohistochemistry essentially as described in Plaas et al. (45). Briefly, mouse legs were fixed in 10% (v/v) neutral-buffered formalin for 48 h, skin and muscle tissue were removed, and joints were decalcified in 5% (w/v) EDTA in PBS for 14 days. Specimens were then processed and embedded in paraffin. Thin sections (4 μm) were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and exposed to a rabbit anti-TSG-6 polyclonal antibody (prepared in collaboration with Dr. J. D. Sandy (Rush University, Chicago, IL) and Affinity Bioreagents (Golden, CO) against the peptide ASVTAGGFQIK, affinity-purified, and shown to recognize recombinant murine TSG-6 (R&D Systems) and rhTSG-6 (39) by Western blotting; see supplemental Fig. 1) at 10 μg/ml (IgG) in 1.5% (v/v) goat serum in PBS for 30 min, washed in PBS for 5 min, and then incubated with AlexaFluor-568 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes; 1:250 in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were co-stained for HA using 5 μg/ml biotinylated bovine cartilage HA-binding protein/link protein complexes (isolated in the A1A1D6 fraction after CsCl gradient centrifugation) followed by AlexaFluor-488-streptavidin (Molecular Probes) as described in Plaas et al. (45). Nuclei were stained with TOTO-3 (Molecular Probes; 1:500 in PBS), and sections were examined by confocal microscopy as detailed previously (45).

Effect of TSG-6 on BMP-2-induced Osteoblast Differentiation—Murine MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells (European Collection of Cell Cultures) (46) and MBA-15.4 pre-osteoblastic marrow-derived cells (47) were seeded on 24-well plates (1.25 × 104 cells/ml) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 10 mm l-glutamine, and antibiotics (100 IU/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml streptomycin). Differentiation into osteoblasts was induced with 100 ng/ml BMP-2 (R&D Systems Europe), and the effects of adding rhTSG-6 (0–10000 ng/ml) or molar equivalents of Link_TSG6 or CUB_C_TSG6 proteins were determined. Cells were cultured for 7 days in a humidified atmosphere with 5% (v/v) CO2 at 37 °C, during which time the culture media (including all factors) was replaced every 72 h. Cells were washed in PBS and freeze-thawed 3 times, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was released by scraping cells into 50 μl of 0.2% (v/v) Nonidet P-40 (Fluka) and subsequent sonication (5 s at 6 watts). ALP activity (pmol/μl of material) was determined using the fluorescent substrate 4-methyl umbelliferyl phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, 10 μl of cell lysate was diluted in 50 μl of 0.16% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, in the wells of a Nunclon Delta (Nunc) plate, and 100 μl of 0.2 mm methyl umbelliferyl phosphate was added. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 45 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of 0.6 m Na2CO3 to each well. Fluorescence was measured using an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and an emission wavelength of 450 nm (with a 435 nm cutoff) on a SPECTRAmax GEMINI microplate spectrofluorometer. The yield of ALP was calculated by the preparation of a standard curve of 0–1000 pmol of 4-methyl umbelliferyl phosphate (Sigma) on the same plate and standardized against the total amount of protein/well (in μg), determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce).

TSG-6 Binding ELISA—The BMP and sRANKL binding activities of TSG-6 and its individual domains were determined colorimetrically using ELISAs. All dilutions, incubations, and washes were performed in standard assay buffer (SAB; PBS containing 0.2% (v/v) Tween 20) and at room temperature unless otherwise indicated. BMPs (-2, -13, and -14 from PeproTech; -3, -4, -5, -6, and -7 from R&D Systems Europe) or sRANKL (PeproTech) were coated overnight on Polysorp (Nunc) microtiter plates (0–30 pmol/well) in PBS at room temperature. After this and all subsequent steps, wells were washed three times with SAB. All wells were blocked for 90 min at 37 °C in SAB containing 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin and then incubated for 4 h with rhTSG-6, Link_TSG6, or CUB_C_TSG6 at 2 or 5 pmol/well for the BMP and sRANKL assays, respectively. Bound TSG-6 and CUB_C_TSG6 were compared by incubation for 45 min with a rabbit polyclonal antiserum (RAH-1) (48) diluted 1:4000 followed by incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich) for an additional 45 min. Bound Link_TSG6 and TSG-6 were compared using the monoclonal antibody Q75 (49) at 1.25 μg/ml followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich), where these were incubated for 45 min each. Disodium p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1 mg/ml in 0.05 m Tris-HCl, 0.1 m NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2·6H2O, pH 9.3, was added, and absorbance values at 405 nm were measured after 30 or 60 min of incubation (for BMP and sRANKL ELISAs, respectively) and corrected against control wells (i.e. those containing no immobilized protein).

sRANKL Binding ELISA—TSG-6 or its individual protein domains (0–30 pmol/well) were coated overnight onto microtiter plates, blocked, and washed as described above. All wells were incubated with 30 ng/well biotinylated-sRANKL (PeproTech) for 4 h, and bound sRANKL was detected with ExtrAvidin alkaline phosphatase (Sigma-Aldrich) as described in Mahoney et al. (19) except that absorbance values at 405 nm were measured after a 60-min development time.

Surface Plasmon Resonance—All experiments were performed on a BIACore 2000 system in HEPES-EP running buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 3 mm EDTA, 0.005% (v/v) surfactant P20) at a constant flow rate of 10 μl/min. BMPs or sRANKL (0.37–0.5 μm in 40 μl of 10 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.0) were coupled onto commercially available CM5 sensor chips preactivated with N-hydroxysuccinimide and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide. After immobilization of these proteins, binding analyses were performed using 0–10 μm rhTSG-6, Link_TSG6, or CUB_C_TSG6, where 100 μl of the protein solution was passed over the sensor chip surface, and maximum equilibrium binding was determined 600 s after the start of the injection. Scatchard analysis was performed to determine the validity of the 1:1 Langmuir association/dissociation model, and data were analyzed with Origin software (MicroCal) using a sum of least squares iterative improvement method. These experiments were performed twice, and an average dissociation constant was calculated.

Statistical Analysis—All data were normalized and expressed as percentages relative to controls. Each set of experiments was repeated at least three times unless otherwise stated. For in vitro work, differences between groups were analyzed using the unpaired Student's t test or a Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test. p < 0.01 was considered significant. For the histomorphometric analysis of distal femurs, a non-parametrical Kruskall-Wallis test was used; p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

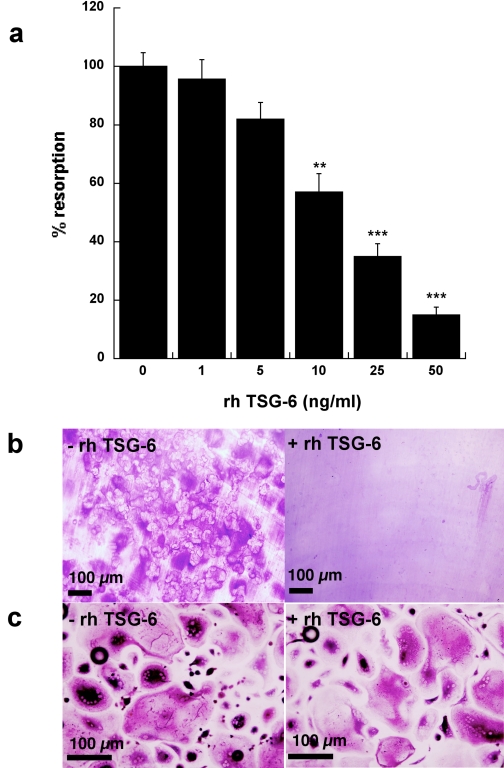

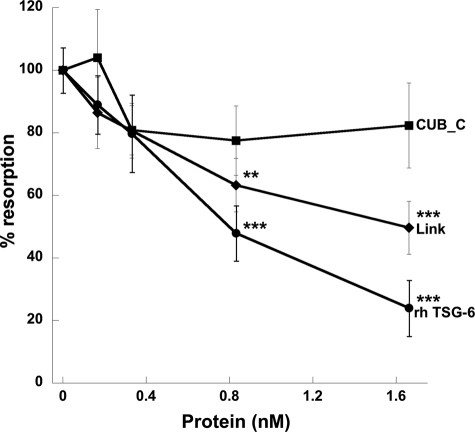

Effect of TSG-6 on sRANKL-induced Osteoclast Formation and Activity—Human PBMCs were incubated with M-CSF and sRANKL for 14 days on coverslips to allow visualization of newly differentiated osteoclasts or for 21 days on dentine slices to assay for activity in the form of lacunar resorption. The addition of full-length rhTSG-6 to these cultures resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of osteoclast-mediated dentine erosion, with an IC50 value of ∼15 ng/ml (∼0.5 nm), as illustrated in Figs. 1, a and b. There was no apparent reduction in the number or the size of the multinucleated osteoclasts formed in TSG-6-treated cultures, as assessed by staining of cells grown on coverslips for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (Fig. 1c); in contrast, lacunar resorption was markedly reduced in the presence of TSG-6 (Fig. 1b). Overall these findings suggest that TSG-6 affects osteoclast activation rather than differentiation. A comparison of the effects of rhTSG-6 with equimolar quantities of Link_TSG6 and CUB_C_TSG6 on sRANKL-induced lacunar resorption (see Fig. 2) revealed that the isolated CUB_C domain has little effect on osteoclast function. In contrast, the Link module retains significant activity, although this is less than that of the intact protein.

FIGURE 1.

TSG-6 inhibits RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis. a, human PBMCs were cultured with sRANKL and M-CSF in the absence or presence of rhTSG-6 (0–50 ng/ml) for 21 days on dentine slices. Lacunar resorption was assessed by light microscopy following staining with toluidine blue. Data are expressed as mean percentage resorption (n = 9) ± S.E., compared with RANKL/M-CSF alone, where ** and *** = p < 0.01, p < 0.001, respectively. b and c, human PBMCs were cultured with sRANKL and M-CSF on dentine slices (b) or coverslips (c) for 21 or 14 days, respectively, in the absence (-) or presence (+) of rhTSG-6 (50 ng). Osteoclast formation or activation was assessed by determining the extent of lacunar resorption (b) or the number of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive multinucleated cells (c), respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Full-length TSG-6 and its isolated Link module inhibit RANKL-induced lacunar resorption. rhTSG-6 (0–50 ng/ml) or equimolar concentrations of Link_TSG6 (Link) or CUB_C_TSG6 (CUB_C) were added to cultures of human PBMCs in the presence of sRANKL and M-CSF. The extent of lacunar resorption of dentine slices was assessed after 21 days. Data are expressed as the mean percentage of resorption with RANKL alone (n = 12) ± S.E., where ** and *** = p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively.

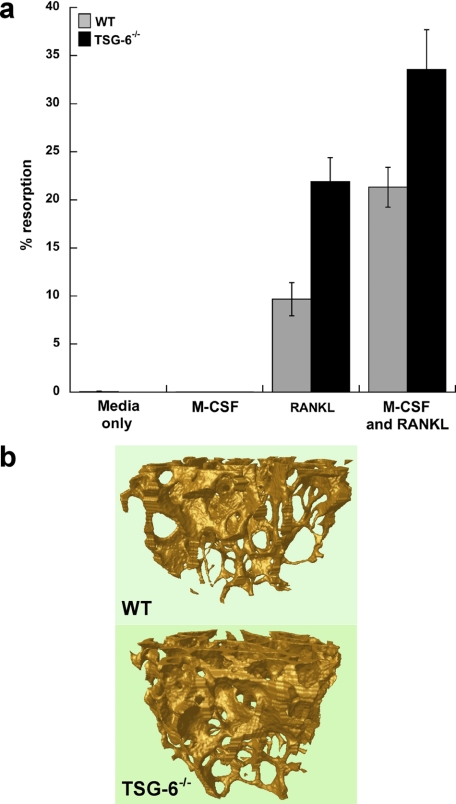

sRANKL-mediated Osteoclastogenesis in TSG-6-deficient Mice—Cells isolated from the marrow of long bones of TSG-6-/- mice or wild type BALB/c animals (WT) were cultured on dentine slices in the presence of M-CSF and sRANKL for 10 days. In the case of the cells derived from TSG-6-deficient mice there was substantially elevated osteoclast-mediated lacunar resorption compared with controls (Fig. 3a), which is consistent with the severe arthritis and tissue damage reported in these animals (35).

FIGURE 3.

TSG-6-/- mice exhibit elevated osteoclast resorptive activity in response to RANKL/M-CSF but greater trabecular bone mass in the absence of challenge. a, osteoclast precursors from the long bone marrow of TSG-6-/- and wild type BALB/c (WT) mice were cultured on dentine slices in the absence (Media) or presence of M-CSF and/or murine sRANKL for 10 days before the determination of lacunar resorption. Data are plotted as mean percentage resorption (n = 4) ± S.E. for WT (black bars) and TSG-6-/- (gray bars) mice. Lacunar resorption was significantly greater in the presence of cells isolated from TSG-6-/- mice as compared with WT; p = 0.03 for cultures containing sRANKL alone and p = 0.004 for those with M-CSF and sRANKL. b, three-dimensional models of the trabecular bone were generated after micro-CT scanning of the hind limb distal femurs of WT (upper panel) and TSG-6-/- (lower panel) male mice. Four mice were analyzed in each case, and representative models are shown.

Micro-CT Analysis of Bones from TSG-6-/- and WT Mice—Micro-CT was used to determine the histomorphometric parameters of the distal femurs from the knees of TSG-6-/- mice and WT controls (both on a BALB/c background). Preliminary analysis on two pairs of mice indicated that the TSG-6 null animals had approximately twice the bone mass of controls (data not shown). More detailed comparisons on four different pairs confirmed that the percentage trabecular volume (Bv/Tv) of the TSG-6-deficient animals (∼17%) is significantly greater than that of the WT mice (∼13%, p = 0.02). TSG-6 knock-out animals also show significant increases in trabecular number (Tb/N) and trabecular thickness (Tb/Th) but not trabecular separation (Tb/Sp) (see Table 1). This is illustrated in Fig. 3b, which compares three-dimensional reconstructions of the trabecular bone network for the TSG-6 null and WT animals. Taken together these findings show that TSG-6-/- mice have increased bone mass compared with wild type littermates, which is contrary to what we had expected based on the effects of TSG-6 on osteoclastic resorption described above and suggests a role for TSG-6 in normal bone homeostasis that might involve modulation of osteoblast differentiation/activity.

TABLE 1.

Histomorphometric parameters for the trabecular regions of distal femurs from TSG-6–/– and WT mice

| Mice | Trabecular volume (Bv/Tv) | Trabecular number (Tb/N) | Trabecular thickness (Tb/Th) | Trabecular separation (Tb/Sp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTa | 12.8 (±0.81) | 2.23 (±0.13) | 0.057 (±0.001) | 0.288 (±0.019) |

| TSG-6–/–a | 17.0 (±0.42)b | 2.66 (±0.04)b | 0.064 (±0.002)b | 0.256 (±0.012) |

Average values shown (n = 4 ± S.E.)

Mean values were compared using a non-parametrical Kruskall-Wallis test and found to differ significantly from WT (p ≤ 0.02)

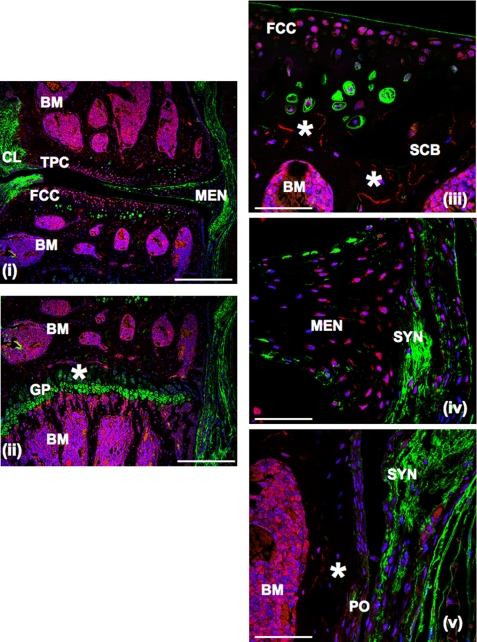

Immunolocalization of TSG-6 in Wild Type Mouse Knee Joints—Immunohistochemistry of wild type murine knee joints (Fig. 4) with anti-TSG-6 antibody showed immunoreactive TSG-6 to be associated with cells in the superficial and midzones of the articular cartilage (panels i and ii) and the lower region of hypertropic cartilage in the epiphyseal growth plate (panel ii) as well as with meniscal fibrochondrocytes (panel iv). In the synovium and periosteum only a few positively stained cells were detected, where these have a flattened or fusiform shape (panels iv and v). Notably, the strongest immunostaining was associated with the cells in the epiphyseal and metaphyseal bone marrow of both the femur and tibia (panels i, ii, iii, and v), at the margins of bone marrow and trabecular bone, and in the extracellular matrix of calcified cartilage adjoining the trabecular bone (indicated by asterisks in panels ii and iii).

FIGURE 4.

Immunolocalization of TSG-6 in normal mouse knee joints. Sections were immunostained for TSG-6 and HA, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Images were taken at 10× (panels i and ii; scale bars = 400 μm) and 63× (panels ii, iv, and v; scale bars = 100 μm) magnifications. TSG-6 immunoreactivity is shown as red, HA as green, and nuclei as blue fluorescence. BM, bone marrow; FCC, femoral condyle cartilage; GP, epiphyseal growth plate cartilage; MEN, meniscus; PO, periosteum; SCB, subcondral bone; SYN, synovium; TPC, tibial plateau cartilage; CL, cruciate ligament.

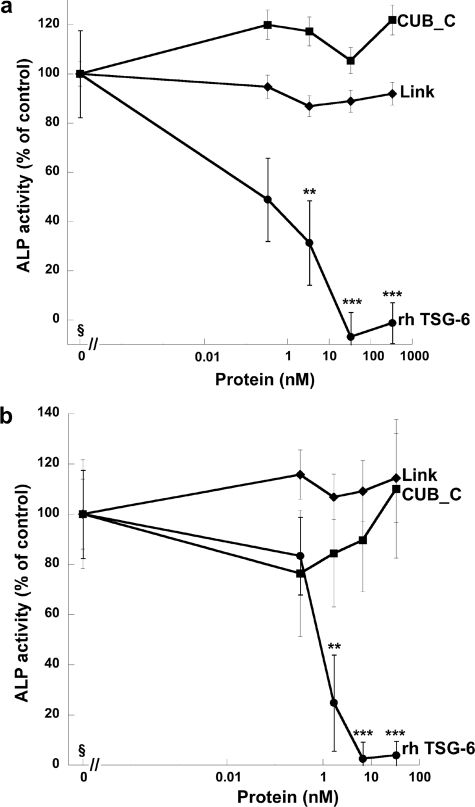

Effect of TSG-6 on BMP-2-induced Osteoblast Differentiation—As a model of BMP-2-induced osteoblast differentiation, we measured the production of ALP (50) by two murine pre-osteogenic cell lines (i.e. stromal MBA-15.4 cells (Fig. 5a) and calvaria-derived MC3T3.E1 cells (Fig. 5b)) cultured in the presence of BMP-2 with and without the addition of TSG-6 proteins. The full-length protein caused a dose-dependent reduction in BMP-2-induced ALP activity, with essentially complete inhibition of differentiation seen at 33 and 6.6 nm TSG-6 for the MBA-15.4 and MC3T3.E1 cell lines, respectively. In contrast, neither Link_TSG6 nor CUB_C_TSG6 had significant effects on ALP release by these cells (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

TSG-6 inhibits BMP-2-induced osteoblastogenesis. The murine pre-osteoblast cell lines MBA-15.4 (a) and MC3T3-E1 (b) were cultured for 7 days with BMP-2 in the absence or presence of rhTSG-6 (at 0–10000 ng/ml) or molar equivalents of Link_TSG6 or CUB_C_TSG6. ALP activity was measured, and values were plotted as the mean ALP activity as a percentage of control (n = 8 ± S.E.) where the addition of BMP-2 alone was normalized to 100%; ** and *** = p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively, compared with BMP-2 alone. MBA-15.4 cells (a) were more responsive to BMP-2 than MC3T3-E1 cells (b), with ALP activity up-regulated by 272 and 37%, respectively. §, data for control cells with no added rhTSG-6, Link_TSG6, or CUB_C_TSG6 are shown as 0 pm protein; data from cells with added TSG-6 proteins are plotted on a log scale.

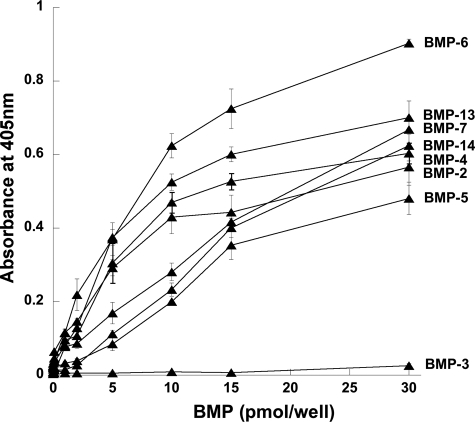

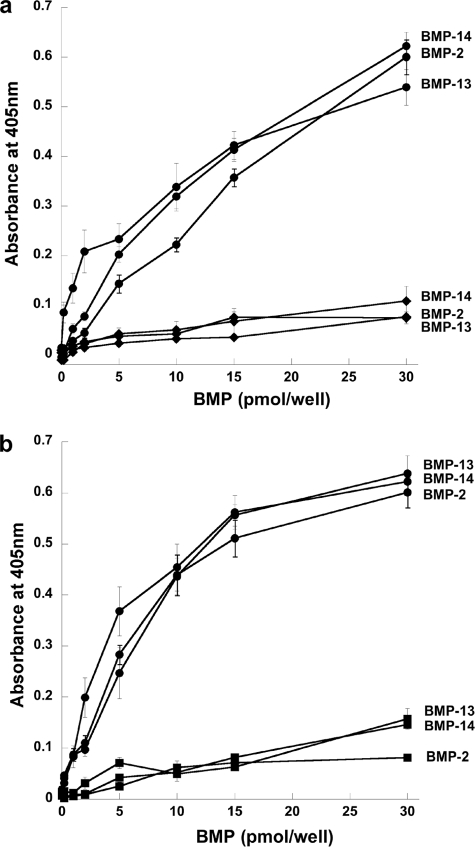

Interactions of TSG-6 with BMPs and sRANKL—The interactions of TSG-6 with BMP-2 and other BMPs were investigated using ELISAs. As illustrated in Fig. 6, BMP-2 and the structurally and functionally related BMP-4, -5, -6, -7, -13, and -14 all interact with TSG-6, whereas there is no apparent binding to the more distantly related BMP-3. Further analysis of BMP-2 and two other representative BMPs (i.e. BMP-13 and -14) revealed that Link_TSG6 and CUB_C_TSG6 (Fig. 7) have a lower level of binding to these immobilized proteins compared with full-length TSG-6. Surface plasmon resonance experiments, where TSG-6 or its individual domains were flowed over BMP-coupled chips, allowed determination of the affinities for these interactions. The dissociation constants for TSG-6 binding to BMP-2, -13, and -14 are all ∼0.2 μm (Table 2). In the case of BMP-2, its interactions with the Link module and CUB_C domain are both ∼11-fold weaker, suggesting that BMP-2 interacts with a composite binding surface on TSG-6 that involves both these domains. Similarly, BMP-13 and -14 have lower affinities for the isolated domains of TSG-6 compared with the full-length protein. However, these BMPs both bind more strongly to the Link module than the CUB_C domain, perhaps indicating that the Link module makes a greater contribution to the interaction surfaces in these cases.

FIGURE 6.

TSG-6 interacts with members of the BMP superfamily. The binding of rhTSG-6 to BMP-coated wells was determined colorimetrically. Values are plotted as the mean absorbance at 405 nm (n = 4 ± S.E.) after a 30-min development time. These data are representative of two or three independent experiments.

FIGURE 7.

BMPs exhibit tighter binding to full-length TSG-6 than to its Link and CUB_C domains. The interactions of full-length rhTSG-6 (•) with immobilized BMP-2, -13, or -14 were compared with Link_TSG6 (♦) (a) or CUB_C_TSG6 (▪) (b). Protein binding was detected using antibodies specific for the Link module or CUB_C domain as appropriate. Values are plotted as the mean absorbance at 405 nm (n = 8 ± S.E.) after 60-min (a) or 30-min (b) development times.

TABLE 2.

Dissociation constants for the interactions of TSG-6 and its isolated domains with BMPs and sRANKL, determined by surface plasmon resonance

| Proteina | Kd TSG-6 | Kd Link_TSG6 | Kd CUB_C_TSG6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | μm | |

| BMP-2 | 0.220b | 2.43 | 2.54 |

| BMP-13 | 0.236 | 2.84 | 6.88 |

| BMP-14 | 0.184 | 1.10 | 10.8 |

| sRANKL | 1.97 | 8.25 | —c |

Each experiment was performed in duplicate with the average values shown here; all interactions conformed to a 1:1 Langmuir model

Dissociation constants are expressed to three significant figures

A value could not be obtained due to the low level of signal (response units) detected, combined with nonspecific binding to the sensor chip

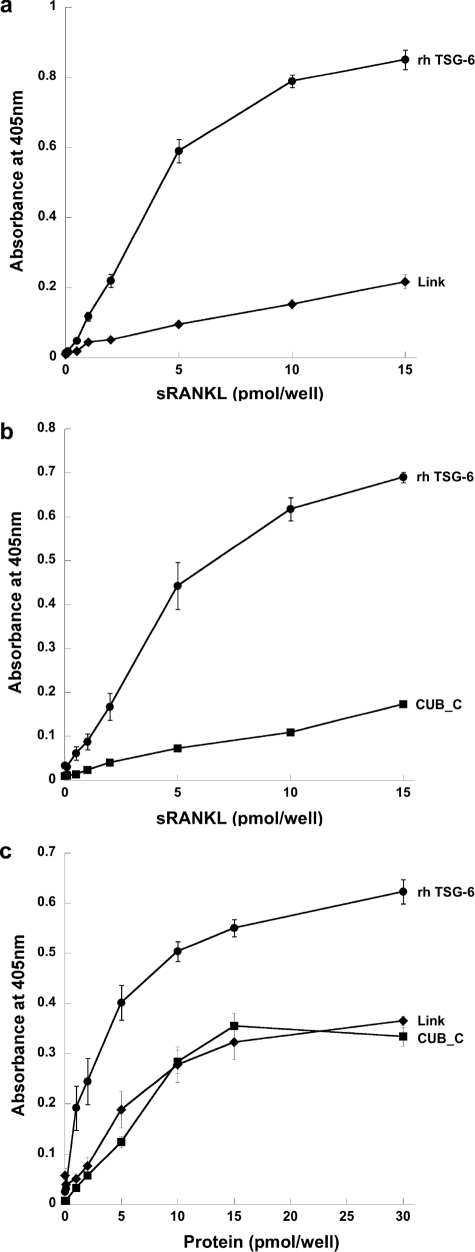

We also investigated the interactions TSG-6, Link_TSG6, and CUB_C_TSG6 with sRANKL by ELISA and surface plasmon resonance. As can be seen from Fig. 8, a and b, full-length TSG-6 binds well to immobilized sRANKL, whereas equivalent amounts (5 pmol/well) of Link_TSG6 or the CUB_C domain show less binding. Similarly, when sRANKL was incubated with plates coated with the TSG-6 proteins (Fig. 8c), the extent of binding to Link_TSG6 and CUB_C_TSG6 was lower than that seen for the full-length protein. These data suggest that, like BMP-2, -13, and -14, sRANKL binds to a composite interaction surface involving both the Link and CUB_C domains of TSG-6. Consistent with this, surface plasmon resonance analysis revealed that full-length TSG-6 bound to immobilized sRANKL with an ∼4-fold higher affinity than the isolated Link module (i.e. about 2 and 8 μm, respectively), although we were unable to obtain a Kd value for CUB_C_TSG6 (see Table 1).

FIGURE 8.

TSG-6 interacts with sRANKL via its Link and CUB_C domains. The interactions of rhTSG-6, Link_TSG6, or CUB_C_TSG6 with sRANKL were compared where either the sRANKL (a and b) or TSG-6 proteins (c) were immobilized on microtiter plates. Absorbance values at 405 nm were measured after 20 min (a), 30 min (b), or 60 min (c) and are plotted as mean values (n = 8 ± S.E.).

As described above, BMP-2 and sRANKL both bind with higher affinity to the intact TSG-6 protein compared with its isolated domains. In addition, the full-length protein has more potent biological effects than the Link_TSG6 or CUB_C_TSG6 domains (see Figs. 2 and 5). Together this provides evidence that TSG-6-mediated inhibition of osteoblastogenesis and of osteoclastic resorption is likely to be mediated via its direct interaction with BMP-2 and RANKL, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Although it is well established that TSG-6 is protective in various experimental models of arthritis (31–35), the exact mechanism(s) by which its effects are mediated remains unclear. Here we have identified two novel functions for TSG-6; it inhibits both sRANKL-induced bone resorption by osteoclasts and BMP-2-induced osteoblast differentiation, which may have a key role in protecting joint tissues during disease and in the regulation of bone homeostasis.

Our functional and ligand binding studies suggest that these activities of TSG-6 are mediated through its interactions with RANKL or BMP-2 (and possibly other BMPs), respectively, where both of these are likely to require composite binding surfaces involving the Link module and CUB_C domain of TSG-6. In this respect, the new binding partners reported here differ from most other TSG-6 ligands (e.g. HA, heparin, bikunin, pentraxin-3, and thrombospondin-1), which have binding sites within the Link module (22). At present, the only known ligand that binds outside this region of TSG-6 is fibronectin, which interacts with the CUB_C domain (12).

In this study we have shown that osteoclasts derived from TSG-6-/- mice give rise to a marked elevation in dentine resorption compared with those from wild type controls, which is consistent with the severe bone erosion seen in TSG-6-/- mice with proteoglycan-induced arthritis (35). These experiments also demonstrate that TSG-6 is produced by bone marrow-derived cells (e.g. pre-osteoclasts and/or stromal cells) in response to stimulation with sRANKL/M-CSF and, thus, that TSG-6 has an autocrine and/or paracrine function in this tissue.

RANKL, the major regulator of osteoclast differentiation (51, 52), is expressed on osteoblasts as well as on dendritic cells and T cells (53, 54) in response to calciotropic factors such as prostaglandin E2, IL-1, and TNF (55). The combination of IL-1 or TNF with IL-17 is particularly potent at inducing RANKL expression, e.g. in synoviocytes (56). RANKL binds to its receptor RANK on mononuclear osteoclast precursors (57), where this interaction not only induces osteoclast differentiation but also stimulates the bone resorbing activity of mature osteoclasts (58). We have shown here that TSG-6 inhibits RANKL-induced bone resorption by human osteoclasts in a dose-dependent manner. Our data suggest that TSG-6 acts at the point of osteoclast activation, since we observed inhibition of dentine erosion, but no reduction in osteoclast number or size when TSG-6 was added to PBMC cultures. It seems reasonable to suggest that TSG-6 might mediate this effect by binding directly to RANKL, thereby blocking its association with RANK; however, further studies are required to demonstrate this definitively.

At present, osteoprotegerin (OPG), a soluble decoy receptor for RANKL, is the only known antagonist of the RANKL/RANK interaction that can effectively inhibit osteoclast maturation and activation in vitro (59). Furthermore, studies on rats with antigen-induced arthritis showed RANKL (expressed on the surface of synovial effector T cells) to be the key mediator of joint damage and bone erosion, where treatment with OPG provided protection against these effects (60). The ability of TSG-6 to inhibit RANKL-induced osteoclast activity, possibly in a manner similar to OPG (i.e. via a direct interaction with RANKL), thus makes it a potential model for the development of therapeutics. The dissociation constant observed here for the TSG-6/sRANKL interaction (∼2 μm) is 3 orders of magnitude higher than that reported for the binding of OPG to RANKL (61). However, as noted by Schneeweis et al. (61), the tight binding observed for OPG/RANKL (Kd = 10 nm) is likely to be due the formation of 1:1 complexes between homodimers of OPG and homotrimers of RANKL, i.e. leading to a high avidity (61). Interestingly, a truncated form of OPG containing the RANKL-binding site but lacking the dimerization domain bound RANKL with a Kd of ∼3 μm. Our study utilized monomeric sRANKL, and it is possible that the interaction of TSG-6 with trimeric RANKL might have a considerably higher affinity; however, this remains to be investigated. In the lacunar resorption assay used here, sRANKL (Mr = 20 kDa) is present at a concentration of 50 ng/ml (2.5 nm), and we observed that rhTSG-6 inhibited dentine erosion with an IC50 of ∼15 ng/ml (∼0.5 nm). By comparison, human recombinant OPG (R&D Systems; 43.5 kDa) was found to have an IC50 value of ∼0.25 nm in this assay.6 This is consistent with a previous investigation of osteoclast formation from arthrosplasty-derived macrophages, showing that human OPG inhibited lacunar resorption with an IC50 of between 50 and 100 ng/ml (∼1.5 nm) (62). Overall this indicates that TSG-6 has a similar potency to OPG in the in vitro inhibition of osteoclastic resorption.

Our observation that unchallenged TSG-6-/- mice have higher trabecular bone mass than wild type controls might at first glance appear to be at odds with the inhibitory effect of TSG-6 on bone erosion described above. However, we hypothesize that, although TSG-6 inhibits osteoclast activity at inflammatory sites, it also has a pivotal role in normal bone homeostasis. This is supported by our finding that TSG-6 is expressed in normal joint tissue (e.g. in bone marrow) and that it significantly reduces the production of ALP (a marker of differentiation) by osteoblast precursors stimulated with BMP-2. Tsukahara et al. (63) have also described inhibition of BMP-2-mediated osteoblastogenesis after overexpression of TSG-6 in human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC) or by the addition of partially purified recombinant TSG-6 proteins to hMSC cultures; binding of TSG-6 to BMP-2 was detected in these systems by immunoprecipitation. The authors proposed that the Link module of TSG-6 is responsible for inhibition of osteoblast differentiation via interaction with BMP-2, based on semiquantitative experiments using deletion mutants where, for example, protein lacking the Link module was found to be inactive. This conclusion is inconsistent with our results that were obtained using defined amounts of pure, highly characterized protein preparations (12–14, 18). It should be noted that, although Tsukahara et al. (63) report little or no inhibition of ALP expression or immunoprecipitation of BMP-2/TSG-6 complex with their deletion mutant lacking the Link module, their data also show a substantial reduction in these effects (compared with full-length TSG-6) with the ΔCUB deletion mutant. We suggest that our data and that of Tsukahara et al. (63) are consistent with BMP-2 binding to a surface that involves both the Link and CUB modules of TSG-6.

The ability of TSG-6 to interact with members of the TGFβ/BMP superfamily closely related to BMP-2 (64), namely BMP-4, -5, -6, -7, -13, and -14, further supports the hypothesis that TSG-6 has a role in bone homeostasis. BMP-2, -6, -7, and -9 are important in inducing the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts (65, 66), whereas most other BMPs are able to stimulate osteogenesis in mature osteoblasts (67–71). TSG-6 might also have regulatory roles in other contexts, e.g. BMP-4 has been implicated in tooth development (72), BMP-2 and -4 are required for limb patterning (73), and BMP-2 is essential for the initiation of fracture repair (74). In this regard TSG-6 may function like some of the known BMP antagonists, i.e. those of the chordin family, noggin (75), gremlin (76), and brorin (77), as well as SOST (78), GDF3 (79), and the recently discovered suppressors of mineralization such as asporin (80), Nov (81), and osteoclast inhibitory lectin (82). Interestingly, we have shown that TSG-6 does not bind to BMP-3, an antagonist of osteogenic BMPs that blocks differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells into osteoblasts (83).

In addition to its role in osteogenesis, BMP-2 can induce cartilage formation and is expressed at elevated levels around lesions (e.g. in osteoarthritis), suggesting that it might contribute to cartilage repair (84). A recent study, looking at the effects of BMP-2 overexpression in murine knee joints, has shown that this protein promotes matrix turnover in cartilage with increased proteoglycan synthesis and aggrecan degradation (85). Furthermore, blocking of BMP-2 activity (by gremlin) in IL-1-damaged cartilage gave rise to an overall decrease in proteoglycan content. It is not yet known whether TSG-6, which is expressed by chondrocytes in response to IL-1 (28, 29), can inhibit BMP-2-mediated functions in cartilage and if so whether this contributes to its protective effects in arthritis.

The significantly higher bone mass that we have observed in the present study in TSG-6-/- mice compared with wild type animals provides compelling evidence that TSG-6 has an in vivo role in the regulation of bone formation. Although we have demonstrated that TSG-6 can inhibit BMP-2-mediated osteoblast differentiation in vitro, we cannot rule out that TSG-6 may also affect the activities of other modulators of osteoblastogenesis (e.g. l-ascorbate and 1,25-(OH)-2-vitamin D3 (86, 87)), which will require further investigation.

In this study we have shown that TSG-6 is expressed in mouse knee joints, where the strongest TSG-6 immunostaining was associated with the cells in the epiphyseal and metaphyseal bone marrow and at the margins of bone marrow and trabecular bone. Our in vitro cell culture experiments are also consistent with TSG-6 being produced by bone marrow-derived cells in mice. OPG and RANKL have been shown to co-localize in the bone marrow lining cells, osteoblasts, and newly embedded osteocytes at sites of bone remodeling in rats (88). In addition, in rat tibiae, ALP activity (a marker of BMP-2-mediated differentiation) has been detected on osteoblasts and some bone marrow fibroblastic stromal cells, in particular those cells closest to the bone surface (89). These observations are indicative that TSG-6 is present within the bone marrow at similar localizations to BMP-2, RANKL, and OPG during bone remodeling.

The above data have led us to hypothesize that TSG-6 might coordinately regulate the activities of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, thus having a key role in bone turnover. The molecular basis for these opposing functions and how they are differentially controlled remains to be determined. What is clear is that TSG-6 is a novel regulator of bone cell biology with potent effects on two processes that are central to both normal physiology and articular joint disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Phil Salmon (SkyScan, Belgium) for micro-CT analysis, Dr. Rachel Locklin (Nuffield Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Oxford) for advice on ALP assays, and Marilyn Rugg (MRC Immunochemistry Unit, Oxford) for production of rhTSG-6 and the Western blot analysis.

This work was supported by Arthritis and Research Campaign Grants 16539 and 17950 (to A. J. D. and C. M. M. and to A. S., A. J. D., and C. M. M., respectively) and ISIS Innovation, Oxford Grant POC 228 (to A. S. and A. J. D.). This work was also supported by National Institutes of Health NIAMS Grant AR051163 (to K. M.). Funding was also received from the CellProm Project, FP6th of the European Community (NMP4-CT-2004-500039 (to D. B.)). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

Author's Choice—Final version full access.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TSG-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-stimulated gene 6; rhTSG-6, recombinant human TSG-6; SAB, standard assay buffer; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; CUB, complement C1r/C1s, Uegf, Bmp1; CUB_C_TSG6, recombinant CUB_C domain of TSG-6; HA, hyaluronan; Link_TSG6, recombinant Link module of TSG-6; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; OPG, osteoprotegrin; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; (s)RANKL, (soluble) receptor activator of NF-κB ligand; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; WT, wild type; IL, interleukin; αMEM, α-minimum essential medium; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; CT, micro-computerized tomography; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; OPG, osteoprotegerin.

D. C. Briggs, T. Ali, D. J. Mahoney, C. M. Milner, and A. J. Day, unpublished information.

D. J. Mahoney, C. M. Milner, A. J. Day, and A. Sabokbar, unpublished information.

References

- 1.Lee, T. H., Wisniewski, H. G., and Vilcek, J. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 116 545-557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milner, C. M., and Day, A. J. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116 1863-1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salustri, A., Garanda, C., Hirsch, E., De Acetis, M., Maccagno, A., Bottazzi, B., Doni, A., Bastone, A., Mantovani, G., Beck Peccoz, P., Salvatori, G., Mahoney, D. J., Day, A. J., Siracusa, G., Romani, L., and Mantovani, A. (2004) Development 131 1577-1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuznetsova, S. A., Day, A. J., Mahoney, D. J., Mosher, D. F., and Roberts, D. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 30899-30908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkar, A. A., Kahmann, J. D., Howat, S. L. T., Bayliss, M. T., and Day, A. J. (1998) FEBS Lett. 428 171-176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuznetsova, S. A., Issa, P., Perruccio, E. M., Zeng, B., Sipes, J. M., Ward, Y., Seyfried, N. T., Fielder, H. L., Day, A. J., Wight, T. N., and Roberts, D. D. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119 4499-4509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wisniewski, H. G., Burgess, W. H., Oppenheim, J. D., and Vilcek, J. (1994) Biochemistry 33 7423-7429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahoney, D. J., Mulloy, B., Forster, M. J., Blundell, C. D., Fries, E., Milner, C. M., and Day, A. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 27044-27055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanggaard, K. W., Karring, H., Valnickova, Z., Thogersen, I. B., and Enghild, J. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 11936-11942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rugg, M. S., Willis, A. C., Mukohpadhyay, D., Hascall, V. C., Fries, E., Fülöp, C., Milner, C. M., and Day, A. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 25674-25686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue, I., Ikeda, R., and Tsukahara, S. (2006) J. Pharmacol. Sci. 100 205-210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuznetsova, S., Mahoney, D. J., Mosher, D. F., Nentwich, H. A., Ali, T., Day, A. J., and Roberts, D. D. (2008) Matrix Biol. 27 201-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohda, D., Morton, C. J., Parkar, A. A., Hatanaka, H., Inagakai, F. M., Campbell, I. D., and Day, A. J. (1996) Cell 86 767-775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blundell, C. D., Mahoney, D. J., Almond, A., DeAngelis, P. L., Kahmann, J. D., Teriete, P., Pickford, A. R., Campbell, I. D., and Day, A. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 49261-49270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahoney, D. J., Whittle, J. D., Milner, C. M., Clark, S. J., Mulloy, B., Buttle, D. J., Jones, G. C., Day, A. J., and Short, R. D. (2004) Anal. Biochem. 330 123-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parkar, A. A., and Day, A. J. (1997) FEBS Lett. 410 413-417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day, A. J., Aplin, R. T., and Willis, A. C. (1996) Protein Expression Purif. 8 9-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higman, V. A., Blundell, C. D., Mahoney, D. J., Redfield, C., Noble, M. E. M., and Day, A. J. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 371 669-684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahoney, D. J., Blundell, C. D., and Day, A. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 22764-22771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blundell, C. D., Almond, A., Mahoney, D. J., DeAngelis, P. L., Campbell, I. D., and Day, A. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 18189-18201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wisniewski, H. G., and Vilcek, J. (2004) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 15 129-146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milner, C. M., Higman, V. A., and Day, A. J. (2006) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34 446-450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forteza, R., Casalino-Matsuda, S., Monzon-Medina, M. E., Rugg, M. S., Milner, C. M., and Day, A. J. (2007) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 36 20-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wisniewski, H. G., Maier, R., Lotz, M., Lee, S., Klampfer, L., Lee, T. H., and Vilcek, J. (1993) J. Immunol. 151 6593-6601 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayliss, M. T., Howat, S. L. T., Dudhia, J., Murphy, J. M., Barry, F. P., Edwards, J. C. W., and Day, A. J. (2001) Osteoarthritis Cartilage 9 42-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochsner, S. A., Day, A. J., Rugg, M. S., Breyer, R. M., Gomer, R. H., and Richards, J. S. (2003) Endocrinology 144 4376-4384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fülöp, C., Szántó, S., Mukhopadhyay, D., Bárdos, T., Kamath, R. V., Rugg, M. S., Day, A. J., Salustri, A., Hascall, V. C., Glant, T. T., and Mikecz, K. (2003) Development 130 2253-2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier, R., Wisniewski, H. G., Vilcek, J., and Lotz, M. (1996) Arthritis Rheum. 39 552-559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margerie, D., Flechtenmacher, J., Buttner, F. H., Karbowski, A., Puhl, W., Schleyerbach, R., and Bartnik, E. (1997) Osteoarthritis Cartilage 5 129-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kehlen, A., Pachnio, A., Thiele, K., and Langner, J. (2003) Arthritis Res. Ther. 5 186-192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mindrescu, C., Thorbecke, G. J., Klein, M. J., Vilcek, J., and Wisniewski, H. G. (2000) Arthritis Rheum. 43 2668-2677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mindrescu, C., Dias, A. A. M., Olszewski, R. J., Klein, M. J., Reis, L. F. L., and Wisniewski, H. G. (2002) Arthritis Rheum. 46 2453-2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bárdos, T., Kamath, R. V., Mikecz, K., and Glant, T. T. (2001) Am. J. Pathol. 159 1711-1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glant, T. T., Kamath, R. V., Bárdos, T., Gál, I., Szántó, S., Murad, Y. M., Sandy, J. D., Mort, J. S., Roughley, P. J., and Mikecz, K. (2002) Arthritis Rheum. 46 2207-2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szántó, S., Bárdos, T., Gál, I., Glant, T. T., and Mikecz, K. (2004) Arthritis Rheum. 50 3012-3022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wisniewski, H. G., Hua, J. C., Poppers, D. M., Naime, D., Vilcek, J., and Cronstein, B. N. (1996) J. Immunol. 156 1609-1615 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Getting, S. J., Mahoney, D. J., Cao, T., Rugg, M. S., Fries, E., Milner, C. M., Perretti, M., and Day, A. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 51068-51076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao, T., La, M., Getting, S. J., Day, A. J., and Perretti, M. (2004) Microcirculation 11 615-624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nentwich, H. A., Mustafa, Z., Rugg, M. S., Marsden, B. D., Cordell, M. R., Mahoney, D. J., Jenkins S. C., Dowling, B., Fries, E., Milner, C. M., Loughlin, J., and Day, A. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 15354-15362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kahmann, J. D., Koruth, R., and Day, A. J. (1997) Protein Expression Purif. 9 315-318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabokbar, A., and Athanasou, N. A. (2003) Methods Mol. Med. 80 101-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wani, M. R., Fuller, K., Kim, N. S., Choi, Y., and Chambers, T. (1999) Endocrinology 140 1927-1935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorensen, W. E., and Cline, H. E. (1987) ACM SIGGRAPH Comp. Graphics 21 163-169 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parfitt, A. M., Drezner, M. K., Glorieux, F. H., Kanis, J. A., Malluche, H., Meunier, P. J., Ott, S. M., and Recker, R. R. (1987) J. Bone Miner. Res. 2 595-610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plaas, A., Osborn, B., Yoshihara, Y., Bai, Y., Bloom, T., Nelson, F., Mikecz, K., and Sandy, J. D. (2007) Osteoarthritis Cartilage 15 719-734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sudo, H., Kodama, H. A., Amagai, Y., Yamamoto, S., and Kasai, S. (1983) J. Cell Biol. 96 191-198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benayahu, D., and Sela, J. (1996) Calcif. Tissue Int. 59 254-258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fujimoto, T., Savani, R. C., Watari, M., Day, A. J., and Strauss, J. F. (2002) Am. J. Pathol. 160 1495-1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lesley, J., English, N. M., Gál, I., Mikecz, K., Day, A. J., and Hyman, R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 26600-26608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bonucci, E., and Nanci, A. (2001) Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 106 129-133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quinn, J. M., Elliott, J., Gillespie, M. T., and Martin, T. J. (1998) Endocrinology 139 4424-4427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asagiri, M., and Takayanagi, H. (2007) Bone (NY) 40 251-264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lacey, D. L., Timms, E., Tan, H. L., Kelley, M. J., Dunstan, C. R., Burgess, T., Elliott, R., Colombero, A., Elliott, G., Scully, S., Hsu, H., Sullivan, J., Hawkins, N., Davy, E., Capparelli, C., Eli, A., Qian, Y. X., Kaufman, S., Sarosi, I., Shalhoub, V., Senaldi, G., Guo, J., Delaney, J., and Boyle, W. J. (1998) Cell 93 165-176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kong, Y. Y., Yoshida, H., Sarosi, I., Tan, H. L., Timms, E., Capparelli, C., Morony, S., Oliveira-dos- Santos, A. J., Van, G., Itie, A. Khoo, W., Wakeham, A., Dunstan, C. R., Lacey, D. L., Mak, T. W., Boyle, W. J., and Penninger, J. M. (1999) Nature 397 315-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suda, T., Takahashi, N., Udagawa, N., Jimi, E., Gillespie, M. T., and Martin, T. J. (1999) Endocr. Rev. 20 345-357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Page, G., and Miossec, P. (2005) Arthritis Rheum. 52 2307-2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakagawa, N., Kinosaki, M., Yamaguchi, K., Shima, N., Yasuda, H., Yano, K., Morinaga, T., and Higashio, K. (1998) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 253 395-400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tanaka, S., Nakamura, K., Takahasi, N., and Suda, T. (2005) Immunol. Rev. 208 30-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simonet, W. S., Lacey, D. L., Dunstan, C. R., Kelley, M., Chang, M. S., Luthy, R., Nguyen, H. Q., Wooden, S., Bennett, L., Boone, T., Shimamoto, G., DeRose, M., Elliott, R., Colombero, A., Tan, H. L., Trail, G., Sullivan, J., Davy, E., Bucay, N., Renshaw-Gegg, L., Hughes, T. M., Hill, D., Pattison, W., Campbell, P., Sander, S., Van, G., Tarpley, J., Derby, P., Lee, R., and Boyle, W. J. (1997) Cell 89 309-319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kong, Y. Y., Feige, U., Sarosi, I., Bolon, B., Tafuri, A., Morony, S., Capparelli, C., Li, J., Elliott, R., McCabe, S., Wong, T., Campagnuolo, G., Moran, E., Bogoch, E. R., Van, G., Nguyen, L. T., Ohashi, P. S., Lacey, D. L., Fish, E., Boyle, W. J., and Penninger, J. M. (1999) Nature 402 304-309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schneeweis, L. A., Willard, D., and Milla, M. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 41155-41164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Itonaga, I., Sabokbar, A., Murray, D. W., and Athanasou, N. A. (2000) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 59 26-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsukahara, S., Ikeda, R., Goto, S., Yoshida, K., Mitsumori, R., Sakamoto, Y., Tajima, A., Yokoyama, T., Toh, S., Furukawa, K., and Inoue, I. (2006) Biochem. J. 15 595-603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen, D., Zhao, M., and Mundy, G. R. (2004) Growth Factors 22 233-241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng, H., Jiang, W., Phillips, F. M., Haydon, R. C., Peng, Y., Zhou, L., Luu, H. H., An, N., Breyer, B., Vanichakarn, P., Szatkowski, J. P., Park, J. Y., and He, T. C. (2003) J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 85 1544-1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kang, Q., Sun, M. H., Cheng, H., Peng, Y., Montag, A. G., Deyrup, A. T., Jiang, W., Luu, H. H., Luo, J., Szatkowski, J. P., Vanichakarn, P. Park, J. Y., Li, Y., Haydon, R. C., and He, T. C. (2004) Gene Ther. 11 1312-1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Benayahu, D., Fried, A., Shamay, A., Cunningham, N., Blumberg, S., and Wientroub, S. (1994) J. Cell. Biochem. 56 62-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Benayahu, D., Fried, A., and Wientroub, S. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 210 197-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fried, A., and Benayahu, D. (1996)) J. Cell. Biochem. 62 476-483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kingsley, D. M. (2001) Novartis Found. Symp. 232 213-222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reddi, A. H. (2001) Arthritis Res. 3 1-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ohazama, A., Tucker, A., and Sharpe, P. T. (2005) J. Dent. Res. 84 603-606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bandyopadhyay, A., Tsuji, K., Cox, K., Harfe, B. D., Rosen, V., and Tabin, C. J. (2006) PLoS Genet. 2 2116-2130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsuji, K., Bandyopadhyay, A., Harfe, B. D., Cox, K., Kakar, S., Gerstenfeld, L., Einhorn, T., Tabin, C. J., and Rosen, V. (2006) Nat. Genet. 38 1424-1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wan, D. C., Pomerantz, J. H., Brunet, L. J., Kim, J. B., Chou, Y. F., Wu, B. M., Harland, R., Blau, H. M., and Longaker, M. T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 26450-26459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gazzerro, E., Pereira, R. C., Jorgetti, V., Olson, S., Economides, A. N., and Canalis, E. (2005) Endocrinology 146 655-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koike, N., Kassai, Y., Kouta, Y., Miwa, H., Konishi, M., and Itoh, N. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 15843-15850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kusu, N., Laurikkala, J., Imanishi, M., Usui, H., Konishi, M., Miyake, A., Thesleff, I., and Itoh, N. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 24113-24117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Levine, A. J., and Brivanlou, A. H. (2006) Cell Cycle 5 1069-1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamada, S., Tomoeda, M., Ozawa, Y., Yoneda, S., Terashima, Y., Ikezawa, K., Ikegawa, S., Saito, M., Toyosawa, S., and Murakami, S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 23070-23080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rydziel, S., Stadmeyer, L., Zanotti, S., Durant, D., Smerdel-Ramoya, A., and Canalis, E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 19762-19772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nakamura, A., Ly, C., Cipetić, M., Sims, N. A., Vieusseux, J., Kartsogiannis, V., Bouralexis, S., Saleh, H., Zhou, H., Price, J. T., Martin, T. J., Ng, K. W., Gillespie, M. T., and Quinn, J. M. W. (2007) Bone (NY) 40 305-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Daluiski, A., Engstrand, T., Bahamonde, M. E., Gamer, L. W., Agius, E., Stevenson, S. L., Cox, K., Rosen, V., and Lyons, K. M. (2001) Nat. Genet. 27 84-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blaney Davidson, E. N., Vitters, E. L., van der Kraan, P. M., and van den Berg, W. B. (2006) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65 1414-1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Blaney Davidson, E. N., Vitters, E. L., van Lent, P. L. E. M., van de Loo, F. A. J., van den Berg, W. B., and van der Kraan, P. M. (2007) Arthritis Res. Ther. 9 R102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Takeuchi, Y., Matsumoto, T., Ogata, E., and Shishiba, Y. (1993) J. Bone Miner. Res. 8 823-830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Partridge, N. C., Frampton, R. J., Eisman, J. A., Michelangeli, V. P., Elms, E., Bradley, T. R., and Martin, T. J. (1980) FEBS Lett. 115 139-142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhu, W. Q., Wang, X., Wang, X. X., and Wang, Z. Y. (2007) J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 35 103-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kondo, Y., Irie, K., Ikegame, M., Ejiri, S., Hanada, K., and Ozawa, H. (2001) J. Bone Miner. Metab. 19 352-358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.