Abstract

The hydroxymethyl group of serine is a primary source of tetrahydrofolate (THF)-activated one-carbon units that are required for the synthesis of purines and thymidylate and for S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet)-dependent methylation reactions. Serine hydroxylmethyltransferase (SHMT) catalyzes the reversible and THF-dependent conversion of serine to glycine and 5,10-methylene-THF. SHMT is present in eukaryotic cells as mitochondrial SHMT and cytoplasmic (cSHMT) isozymes that are encoded by distinct genes. In this study, the essentiality of cSHMT-derived THF-activated one-carbons was investigated by gene disruption in the mouse germ line. Mice lacking cSHMT are viable and fertile, demonstrating that cSHMT is not an essential source of THF-activated one-carbon units. cSHMT-deficient mice exhibit altered hepatic AdoMet levels and uracil content in DNA, validating previous in vitro studies that indicated this enzyme regulates the partitioning of methylenetetrahydrofolate between the thymidylate and homocysteine remethylation pathways. This study suggests that mitochondrial SHMT-derived one-carbon units are essential for folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism in the cytoplasm.

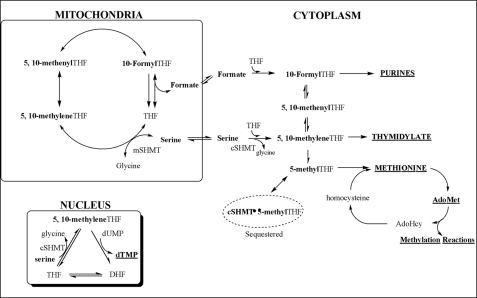

Tetrahydrofolates (THF)3 are present in cells as a family of metabolic cofactors that carry and chemically activate single carbons for a network of biosynthetic pathways referred to as folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism (Fig. 1) (1, 2). Folate metabolism is compartmentalized in the cytoplasm, mitochondria, and the nucleus (2–5). In the cytoplasm, folate-activated carbons are incorporated into the 2nd and 8th positions of the purine ring and are required for the conversion of uridylate to thymidylate and for the methylation of homocysteine to methionine. Methionine can be converted to a methyl donor through its adenosylation to S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet), a required cofactor for the methylation of DNA, RNA, proteins, lipids, and numerous small molecules. Disruptions in folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism, resulting from nutritional deficiencies and/or common genetic variations, impair both DNA synthesis and chromatin methylation (1). Decreased rates of thymidylate synthesis result in increased rates of uracil misincorporation into DNA, whereas decreases in cellular methylation capacity affect both histone and cytosine methylation in chromatin. These genomic alterations are associated with genome instability, altered gene expression, and increased risk for certain cancers, developmental anomalies, and vascular and neurological disorders. However, definitive molecular mechanisms underlying these pathologies have yet to be established.

FIGURE 1.

Folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism. Folate-activated one-carbons are utilized in the synthesis of purines, thymidylate (dTMP), and the methylation of homocysteine to methionine. Methionine can be converted to a methyl donor through its adenosylation to AdoMet. Mitochondria-derived formate traverses to the cytoplasm where it is incorporated into the folate-activated one-carbon pool. Nuclear folate metabolism occurs through the small ubiquitin-related modifier-dependent import of the de novo thymidylate synthase pathway from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (3, 4). SHMT isozymes are present in each of these three compartments and function to generate single carbons from the hydroxymethyl group of serine in the form of 5,10-methylene-THF. The one-carbon unit is labeled in boldface.

Folate-activated one-carbons are derived from serine, histidine, glycine, choline, and purine catabolism, although serine is the primary source of activated carbons for folate- and AdoMet-dependent one-carbon transfer reactions (6) (Fig. 1). The hydroxymethyl group of serine enters the folate-activated one-carbon pool through its THF-dependent conversion to glycine and 5,10-methylene-THF in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT). SHMT is present in both the cytoplasm (cSHMT) and mitochondria (mSHMT), and the SHMT isozymes are encoded on distinct genes, Shmt1 and Shmt2, respectively (7, 8).

Mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism generates formate, a single-carbon molecule, from the amino acids serine, glycine, sarcosine, and dimethylglycine (Fig. 1) (2). Formate effluxes to the cytoplasm where it is incorporated into the folate-activated one-carbon pool through the activity of 10-formyl-THF synthetase. Nuclear folate metabolism occurs through the small ubiquitin-related modifier-dependent translocation of the de novo thymidylate synthase pathway from the cytoplasm to the nucleus during S-phase (3, 4). SHMT isozymes are present in each of these three compartments. Whereas mSHMT is expressed ubiquitously among mammalian cell types, cSHMT exhibits tissue-specific expression patterns (5, 7, 8).

A definitive role for the essentiality of mitochondria in generating folate-activated single carbons for cytoplasmic metabolism has yet to be established. Although the genes that encode the mitochondrial pathway for the folate-dependent conversion of serine to glycine and formate are expressed in mammalian embryonic and tumor cells, the enzyme responsible for the conversion of 5,10-methylene-THF to 5,10-methenyl-THF has yet to be identified in differentiated, nontransformed cells (5). Furthermore, it has been proposed that mitochondria and the mSHMT enzyme may function to generate serine from glycine for gluconeogenesis in adult cells, indicating that mitochondria may not serve as the source of formate for cytoplasmic one-carbon metabolism in all cell types. Although suggested, the ability of cSHMT to serve as a primary source of one-carbons for cytoplasmic one-carbon metabolism has never been investigated. Previous studies in cell cultures have indicated that cSHMT generates methylene-THF for dTMP synthesis through the compartmentation of de novo thymidylate synthesis in the nucleus and serves to inhibit homocysteine remethylation in the cytoplasm by sequestering 5-methyl-THF (9) (Fig. 1). In this study, the metabolic role and essentiality of cSHMT in one-carbon metabolism was investigated in mice.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Shmt1/loxβgeo Targeting Vector—The pKO Scrambler V907 plasmid (Lexicon Genetics, Inc.) was used to generate the targeting vector. First, two synthetic oligonucleotides containing loxP sites were cloned into the BglII/ClaI and BamHI/EcoRI sites of pKO Scrambler; only the BglII site was left intact. Genomic sequences from the Shmt1 gene were amplified by PCR using AB2.2-prime ES cell (Lexicon Genetics) DNA as the template. The 5′ homologous Shmt1 sequence corresponding to 970 bp of intron 6 was cloned into the HpaI and BglII sites of the pKO Scrambler plasmid. The 3′ homologous arm corresponding to 5.0 kb of sequence, including most of intron 7, exon 8, and intron 8, was cloned into the KpnI and SmaI sites, 3′ of the loxP sites of the plasmid. The Shmt1 sequence targeted for deletion was a 355-bp sequence, including 73 bp of intron 6, the 213 bp of exon 7, and 69 bp of intron 7. This fragment was cloned into the XhoI site located between the two loxP sites. Subsequently, the BglII/SalI fragment from the vector pGT1.8IresBgeo (10), which included the IRESβgeo cDNA, was flanked with AscI linkers then cloned into the AscI site of pKO Scrambler, placing the IRESβgeo cDNA between the loxP sites. Finally, the negative selection marker diphtheria toxin A was cloned as an RsrI fragment from the vector pKO SelectDT (Lexicon Genetics, Inc.) into the flanking RsrI site of the targeting vector.

AB2.2 prime ES cells were cultured according to the instructions of The Mouse Kit™ (Lexicon Genetics, Inc.). The targeting vector was linearized with NotI, and 20 μg was electroporated into the ES cells, following the protocols (Lexicon Genetics, Inc.). The transfected ES cells were grown in selection media containing 175 μg/ml G418 for 13 days. Surviving clones were picked and screened for homologous recombination by PCR (Fig. 2A). ES cell DNA was purified according to the instructions of The Mouse Kit™. The forward primer was 5′-GCCTGCTTTGTTGTTTTGATTAGTC-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-AATTGATAACTTCGTATAGCATACATTATACGAAGTTATA-3′. The PCR conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 45 s, 54 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 2 min. The forward primer corresponds to a sequence in intron 6 that is upstream of the sequence included in the targeting vector. The reverse primer corresponds to parts of the loxP oligonucleotide cloned 5′ of exon 7. The presence of a 1.5-kb PCR product indicated that homologous recombination had taken place between the Shmt1 gene and the targeting vector. Over 90% of the G418-resistant clones tested positive for homologous recombination.

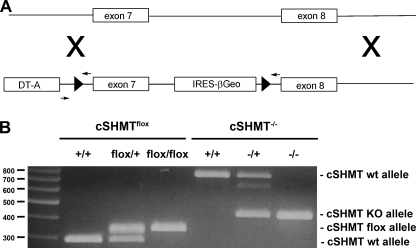

FIGURE 2.

Generation of Shmt1–/– mice. A, Shmt1/loxβgeo targeting vector was inserted into the Shmt1 gene by homologous recombination. The Shmt1/loxβgeo cassette allows for conditional disruption of functional cSHMT protein synthesis and the detection of endogenous Shmt1 transcription via the lacZ reporter gene. Gene disruption is achieved when Shmt1flox/+ mice are mated to CMV-Cre-expressing mice resulting in the deletion of exon 7, which encodes the amino acid sequence for PLP binding, which is essential for the activity of cSHMT. B, homologous recombination of the Shmt1/loxβgeo cassette into the Shmt1 gene is detected as a 348-bp PCR product, whereas the wild type (wt) allele is detected as a 293-bp PCR product. Crossing the Shmt1flox/+ mice to CMV-Cre-expressing mice results in the deletion of exon 7 in the Shmt1 gene. PCR-based genotyping of the wild type Shmt1 allele results in the generation of a 740-bp PCR product, whereas the disrupted allele generates a 460-bp PCR product. PCR primers are indicated by small arrows, loxP sites are designated by filled triangles. KO, knock-out.

Generation of Shmt1flox/+ and Shmt1–/– Mice—A G418-resistant cell line that tested positive for homologous recombination of the targeting vector was injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts at the Cornell Core Transgenic Mouse Facility (Ithaca, NY). Six chimeric B6;129-Shmt1(flox)tm1Stov male founders (referred to as Shmt1flox/+ mice) were obtained. Shmt1flox/+ mice were genotyped by PCR using purified tail genomic DNA (Qiagen) as a template using the forward primer 5′-GACACTGTTCACATCCCTC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-ATGGTAGTGTCAAAGATCC-3′. Both primers correspond to intron 6 sequences that flank the loxP insertion (Fig. 2B). Disruption of the Shmt1 gene in the germ line was achieved by crossing Shmt1flox/+ mice with BALB/c-Tg(CMV-Cre)1Cgn/J (CMV-Cre; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) mice. Mice with a disrupted Shmt1 allele (referred to as Shmt1–/+ mice) were genotyped using the same forward primer as above and the reverse primer 5′-CAAAACATTCGGGAGCCTC-3′. The reverse primer corresponds to an intron 7 sequence located downstream of the 3′ loxP site. Presence of the Cre allele was determined by PCR using the forward primers 5′-CTAGGCCACAGAATTGAAAGATCT-3′ (Il2 internal control) and 5′-ACCAGCCAGCTATCAACTCG-3′ (Cre) and the reverse primers 5′-GTAGGTGGAAATTCTAGCATCATCC-3′ (Il2 internal control) and 5′-TTACATTGGTCCAGCCACC-3′ (Cre) (The Jackson Laboratory). The Cre allele was removed from the germ line by crossing Shmt1–/+ mice with 129SvEv wild type mice; only Shmt1–/+ mice that lacked the Cre allele were chosen for subsequent use and backcrossing.

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation. Blood was collected into heparin-coated tubes by cardiac puncture, and plasma was isolated by centrifugation. Tissues were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with standard use protocols and animal welfare regulations. All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cornell University and conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the National Institutes of Health.

Diets—Mice were fed either a standard chow diet (Harlan Teklad LM-485), AIN93G (referred to as control diet), or AIN-93G diet lacking folic acid and choline (Dyets, Inc., Bethlehem, PA). For studies involving dietary folate deficiency, 129SvEv-Shmt1(N10) mice were randomly weaned at 3 weeks of age onto either the control (AIN-93G) diet or to the modified AIN-93G diet lacking folic acid and choline. The control diet contained 2 mg/kg folic acid and 2.5 g/kg choline bitartrate, and the folate/choline-deficient diet contained 0 mg/kg folic acid and choline bitartrate (Dyets, Inc.). Mice were maintained on the diet for 5, 22, or 32 weeks, as indicated.

Immunoblotting—Total protein was extracted and quantified from tissue (11). Tissue lysis was achieved by sonication in lysis buffer (2% SDS, 100 mm dithiothreitol, 60 mm Tris (pH 6.8)). Proteins (40 μg/well) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred at 4 °C to an Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Corp.) using a Transblot apparatus (Bio-Rad). Following transfer, membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) nonfat skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h followed by overnight incubation in primary antibody at 4 °C. The membranes were washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated overnight with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The membranes were visualized using the SuperSignal® West Pico chemiluminescent substrate system (Pierce). For actin detection, polyclonal rabbit anti-actin antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Abcam) was diluted 1:40,000. For cSHMT detection, sheep anti-mouse cSHMT antibody (12) was diluted 1:10,000, and rabbit anti-sheep IgG secondary antibody (Pierce) was diluted 1:20,000.

Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast Culture—Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from female 129SvEv-Shmt1–/+(N10) mice bred to male 129SvEv-Shmt1–/+(N10) mice at 10–14 days postcoitus. Briefly, embryos were dissected from the uterus into cold sterile PBS. The heads were taken for genotyping, and the eviscerated bodies were cut into 1–2-mm pieces and digested in 0.05% trypsin at 37 °C. Cells were cultured in α-minimal essential medium (Hyclone Laboratories) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories), 0.1 mm nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 1 mm sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

For AdoMet and S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoHcy) analysis in cells, confluent MEFs were washed twice with PBS and cultured for 4 h in defined minimal essential medium (Hyclone Laboratories) that lacked methionine, vitamin B6, and folic acid but supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (dialyzed and charcoal treated), 25 nm leucovorin, and 1 μg/ml pyridoxal phosphate (PLP). The absence of methionine from the culture medium ensures that AdoMet levels reflect homocysteine remethylation capacity and not exogenous methionine availability. The cells were harvested and cell pellets stored at –80 °C.

Determination of AdoMet and AdoHcy Concentrations—The animal feeding cycle was synchronized prior to tissue harvest to ensure AdoMet levels reflected homocysteine remethylation capacity with minimal contributions from dietary methionine. Food was removed 24 h prior to killing the animals. After 12 h, each animal was given one food pellet, and the animals were killed 12 h later by cervical dislocation. Tissues were harvested and immediately flash-frozen and stored at –80 °C until analysis. Frozen tissues or cell pellets were sonicated in 500 μl of 0.1 m NaAcO buffer (pH 6), and protein was precipitated by adding 312 μl of 10% perchloric acid to each sample. After vortexing, samples were centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. AdoMet and AdoHcy were determined as described previously (9). AdoMet and AdoHcy values were normalized to cellular protein content (11).

Plasma and Tissue Folate Concentration—Folate concentration of plasma and tissues was quantified using the Lactobacillus casei microbiological assay as described previously (9).

Uracil Content in Nuclear DNA—Genomic DNA was extracted from 25 to 50 mg of tissue using DNeasy Tissue and Blood Kit (Qiagen), including an incubation with RNase A (Sigma) and RNase T1 (Ambion) for 30 min at 37 °C. 10 μg of DNA was treated with 1 unit of uracil DNA glycosylase (Epicenter) for 1 h at 37 °C. Immediately following incubation, 10 pg of [15N2]uracil (Cambridge Isotopes) was added to each sample as an internal standard, and the sample was dried completely in a speed vacuum. 50 μl of acetonitrile, 10 μl of triethylamine, and 1 μl of 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzyl bromide were added to each sample and incubated for 25 min at 30 °C with shaking at 500 rpm. 50 μl water followed by 100 μl of isooctane were added to each sample. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged. Organic extraction of derived uracil was completed by the removal of the aqueous phase and analysis of the organic phase.

Analysis of uracil-3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzyl bromide was carried out on a Shimadzu QP2010. 1 μl of sample or standard was analyzed in the splitless mode with a purge activation time of 1 min and split vent flow of 50 ml/min with an injection port temperature of 280 °C. Ultrapurity helium gas was used as carrier gas with a linear velocity of 55 ml/min. Separation of derived uracil was obtained by using an XTI-5, 30 m, 0.25-mm inner diameter, 0.25-μm column (Restek), using the following temperature cycles for the oven: 100 °C for 1 min, ramping to 280 °C at 25 °C/min, holding for 5 min, ramping to 300 °C at 5 °C/min, and holding for 5 min. The interface temperature was held at 300 °C with an ion source temperature of 260 °C. Ionization was achieved using the NCI mode using methane as the reagent gas and monitoring for ions 337 m/z for uracil and 339 m/z for [15N2]uracil.

Metabolite Profile from Plasma—Total homocysteine, cystathionine, total cysteine, methionine, glycine, serine, α-aminobutyric acid, N,N-dimethylglycine, and N-methylglycine were assayed in mouse plasma by stable isotope dilution capillary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry as described previously (13, 14).

Statistical Analyses—Differences in genotype distribution were analyzed by the χ2 test. Differences between two groups were determined by Student's t test analysis. Differences among more than two genotypes were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test using the wild type genotype as the control group. Diet × genotype effects were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post hoc test. Groups were considered significantly different when the p value ≤ 0.05. All statistics were performed using JMP IN software, release 5.1.2.

RESULTS

Shmt1 Null Mice Are Viable and Fertile—The targeting vector (Fig. 2A) was designed both to disrupt conditionally the production of functional cSHMT protein and to insert a reporter gene to enable detection of endogenous Shmt1 transcription. To achieve gene disruption, loxP sites were placed both 5′ and 3′ of mouse Shmt1 exon 7, which encodes the amino acid sequence for PLP binding, which is necessary for the activity of cSHMT enzyme (15). To detect endogenous Shmt1 transcriptional activity, a cassette containing the βgeo gene flanked by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and a polyadenylation (poly(A)) signal was inserted 5′ to the loxP site and 3′ to exon 7. The βgeo gene product is a fusion protein consisting of the neomycin resistance gene (neoR) and the lacZ gene, which allowed for G418 selection in transfected ES cells, and serves as the transcriptional reporter to quantify cSHMT transcription in cells. The presence of the IRES enables translation of βgeo following excision of intron 7. The poly(A) signal was placed 3′ of βgeo to enhance the stability of the spliced intron 7.

Successful homologous recombination of the Shmt1/loxβgeo cassette into the Shmt1 gene was demonstrated by PCR-based genotyping. The presence of the Shmt1/loxβgeo (floxed) allele was confirmed by a 348-bp PCR product, whereas the wild type allele was confirmed by a 293-bp PCR product (Fig. 2B). Mice that are heterozygous and homozygous for the floxed allele (Shmt1flox/+ and Shmt1flox/flox) are viable and fertile.

The Shmt1 allele was disrupted by crossing Shmt1flox/+ mice to CMV-Cre-expressing mice, which resulted in the deletion of exon 7 in the Shmt1 gene (Fig. 2B). PCR-based genotyping of the wild type Shmt1 allele results in the generation of a 740-bp PCR product, whereas the disrupted allele generates a 460-bp PCR product (Fig. 2B).

To determine whether Shmt1–/– mice were viable, the Shmt1 genotype distribution was determined from Shmt1–/+ intercrosses (Table 1). A total of 452 pups from 84 litters were examined. The average litter size was 5.4 pups. We found that the Shmt1 genotypes were distributed as expected for Mendelian inheritance of the alleles. The respective ratios of Shmt1+/+, Shmt1–/+, and Shmt1–/– mice were 25.4:49.3:25.2. Both sexes were found at the expected frequency.

TABLE 1.

Shmt1 null mice are viable

Shmt1–/+ mice were intercrossed and their progeny genotyped. The expected genotype distribution was calculated based on a Mendelian distribution. Differences between observed and expected genotype and sex distributions were analyzed by χ2 analysis. p values ≤0.05 were considered significantly different. The number of litters observed was 84. The mean litter size (mean ± S.E.) was 5.4 ± 0.2. p value observed versus expected genotype distribution was not significant, and the p value observed versus expected sex distribution was not significant.

|

Genotype |

Observed genotype distribution |

Expected genotype distribution |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| Shmt1+/+ | 63 | 52 | 115 | 56.5 | 56.5 | 113 |

| Shmt1-/+ | 110 | 113 | 223 | 113 | 113 | 226 |

| Shmt1-/- | 62 | 52 | 114 | 56.5 | 56.5 | 113 |

| Total | 235 | 217 | 452 | 226 | 226 | 452 |

Fertility and maternal lethality of Shmt1 nullizygosity were determined. Shmt1–/– mice were intercrossed, and a total of 90 pups from 13 litters were generated (Table 2). Genotyping indicated that all pups were null for the Shmt1 gene. The expected ratio of male to female pups was observed. The mean litter size was 6.9, and both sexes were observed at the expected distribution. The difference in litter size between the two sets of matings was likely strain-dependent (heterozygous intercrosses are 129SvEv; homozygous intercrosses are on a mixed background of C57Bl/6, BALB/c, and 129SvEv). The data demonstrate that the loss of cSHMT does not affect fertility or result in embryonic lethality.

TABLE 2.

Shmt1 null mice are fertile and do not demonstrate maternal lethality

Shmt1–/– mice were intercrossed and their progeny genotyped to determine fertility and litter size. Differences between observed and expected sex distributions were analyzed by χ2 analysis. p values ≤0.05 were considered significantly different. The number of litters observed was 13. The mean litter size (mean ± S.E.) was 6.9 ± 0.5. p value, observed versus expected sex distribution was not significant.

| Genotype | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shmt1-/- | 41 | 49 | 90 |

| Expected sex distribution | 45 | 45 | 90 |

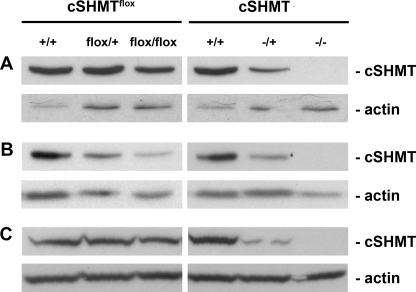

cSHMT Protein Expression in Shmt1flox/+ and Shmt1 Null Mice—The Shmt1flox/+ and Shmt1flox/flox mice demonstrate variable tissue-dependent hypomorphic cSHMT protein levels, as detected by immunoblotting. Liver and kidney tissues from Shmt1flox/+ and Shmt1flox/flox mice exhibit reductions in cSHMT protein levels compared with their Shmt1+/+ siblings, ranging from 0 to an approximate 25% reduction in protein (Fig. 3, A and C). The colon demonstrates the greatest reduction in cSHMT protein, which is reduced by ∼50% in Shmt1flox/+ and by 75–80% in Shmt1flox/flox mice relative to their wild type counterparts (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

cSHMT protein expression in liver (A), colon (B), and kidney (C) of Shmt1flox/+ and Shmt1–/– mice. Tissue lysates were probed with polyclonal anti-cSHMT antibody and polyclonal anti-actin antibody, which served as a loading control.

The Shmt1–/+ and Shmt1–/– mice consistently exhibited a decrease or absence of cSHMT protein levels in all tissues examined, respectively (Fig. 3, A–C). The Shmt1–/+ mice exhibited a 50–80% decrease in cSHMT protein levels in kidney, liver, and colon. No truncated forms of the cSHMT protein were observed in any tissue examined. This indicates that if truncated protein is expressed, it is rapidly degraded because the antibody epitope is located on the amino terminus of the cSHMT protein.

cSHMT Regulates the Remethylation of Homocysteine—Hepatic AdoMet and AdoHcy levels were determined in Shmt1–/– mice on a mixed strain background at ∼6 weeks of age fed the standard chow diet. Livers from Shmt1 wild type 129SvEv, C57Bl/6, and BALB/c mice were used for comparisons. Liver AdoMet levels were elevated 2-fold in the Shmt1–/– mice compared with wild type mice (1.02 versus 0.46 pmol of AdoMet/μg of protein; Table 3). AdoHcy was significantly decreased by 60% in Shmt1–/– mice compared with wild type mice (0.72 versus 1.92 pmol of AdoHcy/μg of protein; Table 3). The cellular methylation potential, represented as the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio, was 4-fold higher in liver from Shmt1–/– mice than observed in wild type mice on a chow diet (1.50 versus 0.38 AdoMet/AdoHcy; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

AdoMet, AdoHcy, and the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio in the liver of Shmt1 null mice on an ad libitum chow diet

The Shmt1 null mice were on a mixed background of C57Bl/6, BALB/c, and 129SvEv. Data represent means ± S.E. Differences between genotypes were analyzed by Student's t test. p values ≤0.05 were considered significantly different.

| Strain | Shmt1 genotype | n | AdoMet | AdoHcy | AdoMet/AdoHcy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmol/μg protein | pmol/μg protein | ||||

| C57Bl/6 | Shmt1+/+ | 9 | 0.33 ± 0.07 | 0.51 ± 0.12 | 0.66 ± 0.08 |

| 129SvEv | Shmt1+/+ | 8 | 0.32 ± 0.07 | 2.64 ± 0.51 | 0.13 ± 0.03 |

| BALB/c | Shmt1+/+ | 9 | 0.71 ± 0.16 | 2.70 ± 0.39 | 0.32 ± 0.07 |

| All strains | Shmt1+/+ | 26 | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 1.92 ± 0.29 | 0.38 ± 0.06 |

| 129SvEv. C57Bl/6.BALB/c | Shmt1-/- | 11 | 1.02 ± 0.32 | 0.72 ± 0.24 | 1.50 ± 0.12 |

| p value, all strains Shmt1+/+vs. Shmt1-/- | 0.02 | 0.02 | <0.0001 |

Hepatic AdoMet and AdoHcy levels were also determined in isogenic 129SvEv-Shmt1–/+(N10) and 129SvEv-Shmt1–/–(N10) mice and their wild type littermates fed a control AIN-93G or folate/choline-deficient diet for 22 or 32 weeks from weaning. Both plasma and liver folate concentrations were significantly reduced in mice fed the folate/choline-deficient diet for 22 and 32 weeks (Table 4). The decrease in plasma and liver folate was independent of Shmt1 genotype except in the case of Shmt1–/+ mice, which demonstrated an increase in liver folate concentration in comparison with Shmt1 wild type mice at 32 weeks.

TABLE 4.

Plasma and liver folate in Shmt1 null mice

Differences between genotypes and diets were analyzed by Student's t test. Genotype × diet effects were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using Tukey's HSD post hoc analysis. Data represent means ± S.E. values. p values ≤0.05 were considered significantly different. n = 3 per group for plasma and n = 4–7 for liver.

|

Age |

22 weeks |

32 weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | Shmt1 genotype | Plasma | Liver | Plasma | Liver |

| ng/ml | fmol/μg protein | ng/ml | fmol/μg protein | ||

| AIN-93G | Shmt1+/+ | 42.27 ± 11.15 | 60.85 ± 8.60 | 35.72 ± 2.26 | 46.00 ± 5.02 |

| Shmt1-/+ | 26.53 ± 1.71 | 56.43 ± 7.72 | 35.29 ± 1.17 | 57.49 ± 6.29 | |

| Shmt1-/- | 31.35 ± 4.25 | 51.11 ± 4.21 | 40.85 ± 2.04 | 41.87 ± 2.13 | |

| AIN-93G minus folate and choline | Shmt1+/+ | 1.06 ± 0.60 | 20.26 ± 4.79 | 1.15 ± 0.10 | 12.82 ± 1.57 |

| Shmt1-/+ | 2.25 ± 0.48 | 29.27 ± 3.97 | 3.15 ± 0.18 | 26.57 ± 5.23 | |

| Shmt1-/- | 2.38 ± 0.22 | 37.60 ± 2.91 | 1.02 ± 0.22 | 21.28 ± 5.37 | |

| p value, diet effect | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| p value, genotype effect | NSa | NS | NS | 0.03b | |

| p value, diet × genotype effect | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

NS means not significant.

Shmt1+/+ is significantly different from Shmt1-/+, p < 0.05, as analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post hoc test for genotype effect.

The folate/choline-deficient diet also resulted in a significant 50% decrease in AdoMet, a significant 65% increase in AdoHcy, and consequently an overall 66% decrease in the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio in all mice after 22 weeks on diet (Table 5). At 32 weeks, AdoMet and the AdoMet/AdoHcy were also significantly decreased by ∼60 and 75%, respectively (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Liver AdoMet, AdoHcy, and the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio values in isogenic Shmt1 null mice

Differences between diets were analyzed by Student's t test. Differences among genotypes were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using Tukey's HSD post hoc analysis. Genotype × diet effects were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using Tukey's HSD post hoc analysis. Data represent mean ± S.E. values. p values ≤0.05 were considered significantly different. n = 3–7 per group, except n = 2 for Shmt1–/– mice on the control AIN-93G, as two samples failed during analysis.

|

Age |

22 weeks |

32 weeks |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | Shmt1 genotype | AdoMet | AdoHcy | AdoMet/AdoHcy | AdoMet | AdoHcy | AdoMet/AdoHcy |

| pmol/μg protein | pmol/μg protein | pmol/μg protein | pmol/μg protein | ||||

| AIN-93G | Shmt1+/+ | 1.27 ± 0.17 | 1.39 ± 0.20 | 1.00 ± 0.16 | 1.36 ± 0.26 | 1.21 ± 0.31 | 1.37 ± 0.33 |

| Shmt1-/+ | 1.11 ± 0.15 | 0.71 ± 0.17 | 1.81 ± 0.35 | 1.10 ± 0.22 | 0.70 ± 0.21 | 2.16 ± 0.45 | |

| Shmt1-/- | 1.44 ± 0.35 | 0.86 ± 0.10 | 1.65 ± 0.21 | 0.85 ± 0.17 | 0.85 ± 0.30 | 1.29 ± 0.32 | |

| AIN-93G minus folate and choline | Shmt1+/+ | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 2.29 ± 0.24 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 1.52 ± 0.21 | 0.27 ± 0.02 |

| Shmt1-/+ | 0.69 ± 0.14 | 1.23 ± 0.20 | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.16 | 0.97 ± 0.14 | 0.66 ± 0.19 | |

| Shmt1-/- | 1.01 ± 0.26 | 1.37 ± 0.15 | 0.78 ± 0.18 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.27 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | |

| p value, diet effect | 0.0004 | 0.002 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NSa | <0.0001 | |

| p value, genotype effect | 0.11 | 0.0005b | 0.0009b | NS | NS | 0.03c | |

| p value, diet × genotype effect | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

NS means not significant.

Shmt1+/+ is significantly different from Shmt1-/+ and Shmt1-/-, p < 0.05, as analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post hoc test for genotype effect.

Shmt1-/+ is significantly different from Shmt1-/-, p < 0.05, as analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post hoc test for genotype effect.

Shmt1 genotype also influenced liver AdoMet, AdoHcy, and the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio after 22 weeks on diet. Shmt1–/– mice tended to have increased AdoMet (p = 0.11; Table 5) in comparison with their wild type littermates. Wild type mice had increased AdoHcy and a decreased AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio in comparison with Shmt1–/+ and Shmt1–/– mice. The genotype-dependent differences observed in these markers of homocysteine remethylation were more pronounced in animals fed the folate/choline-deficient diet. Shmt1–/– mice had significantly more AdoMet than wild type mice fed the folate/choline-deficient diet (1.01 versus 0.37 pmol of AdoMet/μg of protein; p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's HSD post-hoc analysis). Wild type mice had significantly more liver AdoHcy and a decreased AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio in comparison with both Shmt1–/+ and Shmt1–/– mice (2.29 versus 1.23 and 1.37 pmol of AdoHcy/μg of protein; 0.17 versus 0.55 and 0.78 AdoMet/AdoHcy; p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's HSD post-hoc analysis; Table 5).

No changes in AdoMet, AdoHcy, and the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio were observed in wild type and Shmt1–/+ mice on either diet at 32 weeks in comparison with mice on diet for 22 weeks (Table 5). Also, no differences in AdoHcy or the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio were observed between Shmt1–/– mice fed either diet for 22 or 32 weeks. However, at 32 weeks, Shmt1–/– mice demonstrated a significant decrease in AdoMet on both diets in comparison with their Shmt1–/– counterparts at 22 weeks (0.53 versus 1.22 pmol of AdoMet/μg of protein; p = 0.005, Student's t test; Table 5). Consequently, a similar timedependent decrease in the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio was also observed in Shmt1–/– mice (0.76 versus 1.20; p = 0.03, Student's t test; Table 5). As a result, Shmt1–/– mice had a significantly reduced AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio in comparison with Shmt1–/+ mice at 32 weeks (0.76 versus 1.41; p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's HSD post-hoc analysis; Table 5).

Finally, AdoMet and AdoHcy levels were also determined in MEFs derived from 129SvEv-Shmt1–/+(N10) mice. Three independent MEF lines for each Shmt1 genotype were derived by intercrossing Shmt1–/+ mice. No significant differences in AdoMet or AdoHcy were observed among the Shmt1 genotypes (Table 6). However, the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio tended to be higher when comparing Shmt1–/+ or Shmt1–/– MEFs to Shmt1+/+ MEFs. When the AdoMet/AdoHyc ratios from the Shmt1–/– and Shmt1–/– MEF lines were combined, the ratio was significantly higher in comparison with wild type MEFs (0.87 versus 0.74; Table 6).

TABLE 6.

AdoMet, AdoHcy, and the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio in Shmt1 null mouse embryonic fibroblasts

At confluency, MEFs were methionine-starved for 4 h. Data represent mean ± S.E. values derived from three independent MEF lines per genotype. Each line was cultured in duplicate. Differences among genotypes were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with the Dunnet's post hoc test using Shmt1 wild-type cells as the reference. When Shmt1–/+ and Shmt1–/– values were combined, differences between groups were analyzed by Student's t test. p values ≤0.05 were considered significantly different.

| Shmt1 genotype | AdoMet | AdoHcy | AdoMet/AdoHcy |

|---|---|---|---|

| pmol/μg protein | pmol/μg protein | ||

| Shmt1+/+ | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 0.74 ± 0.03 |

| Shmt1-/+ | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.03 |

| Shmt1-/- | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 0.87 ± 0.05 |

| Shmt1-/+ + Shmt1-/- | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.02 |

| p value, Shmt1+/+vs. Shmt1-/+ | 0.97 | 0.68 | 0.07 |

| Shmt1-/- | 0.41 | 0.89 | 0.08 |

| p value, Shmt1+/+vs. Shmt1-/+ + Shmt1-/- | 0.34 | 0.80 | 0.02 |

Shmt1 Heterozygosity Is Associated with Increased Uracil Misincorporation in Liver Nuclear DNA—The folate/choline-deficient diet was not associated with increased uracil in liver genomic DNA at 32 weeks (Table 7). However, Shmt1–/+ mice tended to have increased uracil incorporation in genomic DNA relative to both wild type and Shmt1–/– mice (p = 0.08) on the AIN93G diet. The difference in uracil content was significant when comparing Shmt1+/+ and Shmt1–/+ mice fed the control AIN-93G diet (0.13 versus 0.58 pg of uracil/μg of DNA; p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA, Tukey's HSD post-hoc analysis; Table 7). Under conditions of folate deficiency, the Shmt1–/– exhibited the lowest levels of uracil in nuclear DNA.

TABLE 7.

Liver uracil content in genomic DNA

Differences between diets were analyzed by Student's t test. Differences among genotypes and genotype × diet effects were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using Tukey's HSD post hoc analysis. Data represent mean ± S.E. values. p values ≤0.05 were considered significantly different. n = 4–7 per group.

|

Age |

32 weeks, liver uracil |

|

|---|---|---|

| Diet | Shmt1 genotype | |

| pg uracil/μg DNA | ||

| AIN-93G | Shmt1+/+ | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

| Shmt1-/+ | 0.58 ± 0.16 | |

| Shmt1-/- | 0.33 ± 0.08 | |

| AIN-93G minus folate and choline | Shmt1+/+ | 0.36 ± 0.07 |

| Shmt1-/+ | 0.32 ± 0.08 | |

| Shmt1-/- | 0.15 ± 0.02 | |

| p value, diet effect | NSa | |

| p value, genotype effect | 0.08 | |

| p value, diet × genotype effect | 0.03b | |

NS means not significant.

Shmt1+/+ is significantly different from Shmt1-/+ on control diets, p < 0.05, as analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post hoc test for genotype effect.

cSHMT Influences Metabolic Markers of the Trans-sulfuration Pathway—Plasma metabolites associated with homocysteine remethylation and metabolism were analyzed in wild type, Shmt1flox/+, and Shmt1flox/flox mice fed either a control or folate/choline-deficient diet for 5 weeks. The folate/choline-deficient diet significantly increased plasma homocysteine in all mice by ∼25–30% (Table 8). The folate/choline-deficient diet was also associated with a significant decrease in plasma methionine, N,N-dimethylglycine, and N-methylglycine (Table 8). Neither diet nor Shmt1 genotype influenced plasma serine or glycine. Shmt1 genotype influenced three markers of the transsulfuration pathway, which results in the metabolism of homocysteine to cysteine. Cystathionine was significantly decreased in Shmt1flox/+, and to a lesser degree in Shmt1flox/flox mice, fed the folate/choline-deficient diet in comparison with wild type mice fed the same diet. Also, Shmt1flox/flox mice had increased plasma cysteine in comparison with Shmt1+/+ mice. Furthermore, Shmt1flox/flox mice exhibited mildly elevated increased α-aminobutyric acid when fed the folate/choline-deficient diet.

TABLE 8.

Metabolic profile of plasma from hypomorphic Shmt1flox/+ mice

Differences between diets were analyzed by Student's t test. Differences among genotypes and genotype × diet effects were analyzed by one or two-way ANOVA using Tukey's HSD post hoc analysis. Data represent mean ± S.E. values. p values ≤0.05 were considered significantly different. n = 5–7 per group.

|

Diet |

p value |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Metabolite |

AIN-93G |

AIN-93G minus folate and choline |

|||||||

| Shmt1+/+ | Shmt1flox/+ | Shmt1flox/flox | Shmt1+/+ | Shmt1flox/+ | Shmt1flox/flox | Diet effect | Genotype effect | Diet × genotype effect | |

| Homocysteine (μm) | 4.0 ± 1.6 | 4.2 ± 1.9 | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 5.3 ± 2.2 | 4.9 ± 2.2 | 6.3 ± 2.6 | 0.0003 | NSa | NS |

| Cystathionine (nm) | 1120 ± 457 | 1226 ± 548 | 1169 ± 442 | 1391 ± 568 | 971 ± 434 | 1228 ± 501 | NS | NS | 0.05b |

| Cysteine (μm) | 160 ± 65 | 165 ± 74 | 182 ± 69 | 150 ± 61 | 174 ± 78 | 177 ± 72 | NS | 0.007c | NS |

| α-Aminobutyric acid (μm) | 7.4 ± 3.0 | 9.0 ± 4.0 | 5.0 ± 1.9 | 7.8 ± 3.2 | 6.8 ± 3.1 | 9.9 ± 4.1 | NS | NS | 0.03d |

| Methionine (μm) | 59.5 ± 24.3 | 60.5 ± 27.1 | 43.1 ± 16.3 | 44.5 ± 18.2 | 41.5 ± 18.6 | 43.4 ± 17.7 | 0.01 | NS | NS |

| Glycine (μm) | 349 ± 143 | 395 ± 177 | 348 ± 132 | 358 ± 146 | 359 ± 161 | 314 ± 128 | NS | NS | NS |

| Serine (μm) | 185 ± 75 | 188 ± 84 | 149 ± 56 | 161 ± 66 | 153 ± 69 | 159 ± 65 | NS | NS | NS |

| Dimethylglycine (μm) | 7.78 ± 3.18 | 6.57 ± 2.94 | 6.90 ± 2.61 | 6.37 ± 2.60 | 6.38 ± 2.85 | 5.31 ± 2.17 | 0.05 | NS | NS |

| Methylglycine (μm) | 1.39 ± 0.57 | 1.50 ± 0.67 | 1.45 ± 0.55 | 1.48 ± 0.60 | 1.23 ± 0.55 | 1.04 ± 0.42 | 0.03 | NS | NS |

NS means not significant.

Folate/choline-deficient Shmt1+/+ is significantly different from Shmt1flox/+, p < 0.05, as analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post hoc test for diet × genotype effect.

Shmt1+/+ is significantly different from Shmt1flox/flox, p < 0.05, as analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post hoc test for genotype effect.

Control diet Shmt1flox/flox is significantly different from control diet Shmt1flox/+ and folate/choline-deficient Shmt1flox/flox, p < 0.05, as analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post hoc test for diet × genotype effect.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms the metabolic role of cSHMT in a mammalian model system, and it establishes the essentiality of the cSHMT enzyme in mammalian systems. The Shmt1–/– mice are viable and fertile and exhibit no obvious phenotype, indicating Shmt1 is not an essential gene. This result is in contrast to a study of Caenorhabditis elegans where Shmt1 disruption elicited a maternal lethal phenotype (16). Previous studies in MCF-7 cell culture models indicated that cSHMT regulates the partitioning of 5,10-methylene-THF between the homocysteine remethylation and de novo thymidylate synthesis pathway (9). Increased expression of cSHMT in these cells facilitated the synthesis of thymidylate and depressed levels of AdoMet because of the sequestration of 5-methyl-THF by cSHMT, which makes this folate cofactor unavailable for methionine synthase (Fig. 1). Consistent with these results, Shmt1–/– mice exhibited elevated levels of AdoMet and decreased levels of AdoHcy, which exists in equilibrium with homocysteine. The differences observed between Shmt1+/+ and Shmt1–/– mice were most pronounced in mice fed a folate/choline-deficient diet for 22 weeks. The magnitude of this effect was more subtle in MEFS, which is not surprising given the high levels of cSHMT in liver (and kidney) relative to other tissues (8).

Shmt1–/– mice appear to lose the ability to accumulate AdoMet overtime, as these mice exhibited a time-dependent decrease in hepatic AdoMet after 32 weeks on diet. The decrease in liver AdoMet was not associated with decreased plasma or hepatic folate concentrations. It is known that AdoMet regulates a number of enzymes involved in the synthesis and catabolism of methionine (reviewed in Ref. 17). For example, cystathionine-β-synthase and cystathionase, members of the unidirectional catabolism of homocysteine, and thus its removal from the methionine cycle, are activated by AdoMet. AdoMet also acts as an inhibitor of methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase, which is the enzyme responsible for the production of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, the substrate of methionine synthase. cSHMT, by regulating cellular AdoMet concentrations, may affect rates of homocysteine catabolism, as indicated by the Shmt1 genotype-dependent changes in cystathionine, cysteine, and α-aminobutyric acid.

We have previously shown that cSHMT acts to preferentially shuttle one-carbons into thymidylate biosynthesis (9), which may result from the nuclear translocation of cSHMT and the de novo thymidylate synthase pathway during S-phase of the cell cycle (3). Consistent with these previous findings, here we observed an increase in DNA uracil content in the livers of Shmt1–/– and Shmt1–/+ mice compared with wild type mice, but only when fed the folate-sufficient AIN93G diet (Table 7). Surprisingly, Shmt1–/– mice fed the folate/choline-deficient diet had the lowest levels of uracil in DNA compared with Shmt1+/+ and Shmt1–/+ mice fed the same folate/choline-deficient diet. These data suggest that cSHMT prevents uracil misincorporation into DNA under folate sufficient conditions presumably through nuclear thymidylate synthesis, but that this protection is lost under folate-deficient conditions. Loss of cSHMT expression under conditions of folate deficiency may promote efficient de novo thymidylate synthesis in the cytoplasm by mechanisms yet to be established.

Finally, this study affirms the importance of mitochondrial folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism in the generation of formate for cytoplasmic folate-dependent biosynthetic pathways. Although cSHMT has been shown to preferentially supply one-carbons for thymidylate biosynthesis (3, 9), cSHMT is not an essential source of folate-activated one-carbons. The data do support a regulatory role for cSHMT in the remethylation of homocysteine and maintenance of AdoMet levels. Ongoing studies will determine whether loss of cSHMT in the context of dietary folate deficiency sensitizes mice to folate-related pathologies and developmental anomalies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sylvia Allen, Rachel Slater, Donald Anderson, and Anna Beaudin for technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK58144 from the USPHS. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: THF, tetrahydrofolate; AdoMet, S-adenosylmethionine; AdoHcy, S-adenosylhomocysteine; SHMT, serine hydroxymethyltransferase; cSHMT, cytoplasmic serine hydroxymethyltransferase; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; mSHMT, mitochondrial serine hydroxymethyltransferase; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PLP, pyridoxal phosphate; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ES, embryonic stem; IRES, internal ribosome entry site.

References

- 1.Stover, P. J. (2004) Nutr. Rev. 62 S3–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appling, D. R. (1991) FASEB J. 5 2645–2651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woeller, C. F., Anderson, D. D., Szebenyi, D. M., and Stover, P. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 17623–17631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson, D. D., Woeller, C. F., and Stover, P. J. (2007) Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 45 1760–1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen, K. E., and MacKenzie, R. E. (2006) BioEssays 28 595–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townsend, J. H., Davis, S. R., Mackey, A. D., and Gregory, J. F., III (2004) Am. J. Physiol. 286 G588–G595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stover, P. J., Chen, L. H., Suh, J. R., Stover, D. M., Keyomarsi, K., and Shane, B. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 1842–1848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girgis, S., Nasrallah, I. M., Suh, J. R., Oppenheim, E., Zanetti, K. A., Mastri, M. G., and Stover, P. J. (1998) Gene (Amst.) 210 315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbig, K., Chiang, E. P., Lee, L. R., Hills, J., Shane, B., and Stover, P. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 38381–38389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mountford, P., Zevnik, B., Duwel, A., Nichols, J., Li, M., Dani, C., Robertson, M., Chambers, I., and Smith, A. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 4303–4307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bensadoun, A., and Weinstein, D. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 70 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, X., Szebenyi, D. M., Anguera, M. C., Thiel, D. J., and Stover, P. J. (2001) Biochemistry 40 4932–4939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stabler, S. P., Lindenbaum, J., Savage, D. G., and Allen, R. H. (1993) Blood 81 3404–3413 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen, R. H., Stabler, S. P., and Lindenbaum, J. (1993) Metabolism 42 1448–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szebenyi, D. M., Liu, X., Kriksunov, I. A., Stover, P. J., and Thiel, D. J. (2000) Biochemistry 39 13313–13323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vatcher, G. P., Thacker, C. M., Kaletta, T., Schnabel, H., Schnabel, R., and Baillie, D. L. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 6066–6073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelstein, J. D. (2000) Semin. Thromb. Hemostasis 26 219–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]