Abstract

Hypoxia/reoxygenation stress induces the activation of specific signaling proteins and activator protein 1 (AP-1) to regulate cell cycle regression and apoptosis. In the present study, we report that hypoxia/reoxygenation stress activates AP-1 by increasing c-Jun phosphorylation and DNA binding activity through activation of Polo-like-kinase 3 (Plk3) resulting in apoptosis. The specific effect of hypoxia/reoxygenation stress on Plk3 activation resulting in c-Jun phosphorylation was the opposite of UV irradiation-induced responses that are meanly independent on activation of the stress-induced JNK signaling pathway in human corneal epithelial (HCE) cells. The effect of hypoxia/reoxygenation stress-induced Plk3 activation on increased c-Jun phosphorylation and apoptosis was also mimicked by exposure of cells to CoCl2. Hypoxia/reoxygenation activated Plk3 in HCE cells to directly phosphorylate c-Jun proteins at phosphorylation sites Ser-63 and Ser-73, and to increase DNA binding activity of c-Jun, detected by EMSA. Further evidence demonstrated that Plk3 and phospho-c-Jun were immunocolocalized in the nuclear compartment of hypoxia/reoxygenation stress-induced cells. Increased Plk3 activity by overexpression of wild-type and dominantly positive Plk3 enhanced the effect of hypoxia/reoxygenation on c-Jun phosphorylation and cell death. In contrast, knocking-down Plk3 mRNA suppressed hypoxia-induced c-Jun phosphorylation. Our results provide a new mechanism indicating that hypoxia/reoxygenation induces Plk3 activation instead of the JNK effect to directly phosphorylate and activate c-Jun, subsequently contributing to apoptosis in HCE cells.

Adequate oxygen supply is required for normal tissue function. Vascular deficiency and physical isolation from oxygen sources are the usual causes of oxygen deprivation in tissues (hypoxia). Hypoxic conditions develop in most solid tumors as a result of insufficient blood supply. Cancer cells acquire genetic and adaptive changes allowing them to survive and proliferate in a hypoxic microenvironment. In the cornea, hypoxia leads to pathological conditions in the cornea, such as neovascularization, re-epithelialization attenuation, and apoptosis (1–5). Hypoxia-induced cellular responses include activation of signaling events and gene expression that control important cellular function affecting cell cycle progression and apoptosis. Cellular responses to hypoxia are complex and dependent upon different levels of oxygen tension (6). Furthermore, these cellular responses determine hypoxia-affected organs. The signaling pathways underlying the cellular response to hypoxic stress most likely consist of sensors, signal transducers, and effectors (7). Although the hypoxic sensors have been identified (8, 9), the molecular entities responsible for transducing damage signals to specific effectors are just beginning to be revealed. Recent studies indicate that both ATM/ATR and Chk were activated in hypoxia-treated cells, suggesting that there may be DNA damage. Further downstream, hypoxia stimulates increased phosphorylation of p53, a major molecule executing DNA damage (10, 11). In addition, hypoxia-induced cellular responses resemble the effects of other stress stimuli, including UV irradiation, reactive oxygen species (ROS),2 and osmotic shock (12, 13). For example, hypoxic stress activates MAP kinases including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) that may subsequently activate c-Jun and may also interact with hypoxiainducible factor 1 (Hif-1) (14–17). Other cellular responses involve transcriptional changes in hypoxia-responsive genes by Hif-1 and AP-1 (18–21). The transcription factor AP1 is a homodimer/heterodimer formed by c-Jun and c-Jun/c-Jun and c-Fos or ATF-2 etc. However, there is no firm evidence to date indicating the linkage of hypoxia-induced AP-1/c-Jun activation to a particular signaling pathway.

Mammalian cells from different tissues contain at least four Polo-like kinases (Plk1, Plk2, Plk3, and Plk4) that exhibit marked sequence homology to Drosophila Polo (22–26). As cells progress through the cell cycle, Plk proteins undergo substantial changes in abundance, kinase activity, or subcellular localization. Plk3 shares one or two stretches of conserved amino acid sequences termed Polo box, and contains similar phospho-serine/threonine-containing motifs for interactions with phosphoserine and phosphothreonine. Plk3 is a multifunctional protein and involves stress-induced signaling pathways in various cell types (27–30). Plk3 proteins are rapidly activated upon stress stimulation including ionizing radiation (IR), ROS, and methylmethane sulfonate (MMS) (31). Plk3 is predominantly localized around the nuclear membrane. In Plk3-activated cells, Plk3 appears to be localized to mitotic apparatuses such as spindle poles and mitotic spindles (27). The function of Plk3 involves regulation of programmed cell death. Expression of a constitutively active Plk3 results in rapid cell shrinkage, frequently leading to the formation of cells with an elongated, unsevered midbody. Ectopic expression of constitutively active Plk3 induces apparent G2/M arrest followed by apoptosis (32, 33). These studies strongly suggest that Plk3 plays an important role in the regulation of microtubule dynamics, centrosomal function, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis (34). In previous studies, we found that UV stress-induced c-Jun phosphorylation through activation of the JNK signaling pathway and Plk3; however, JNK plays a dominant role in the stress-induced apoptotic effect (35). In the present study, we provide interesting and definitive evidence in corneal epithelial cells that hypoxia-induced activation of AP-1 and c-Jun results in apoptosis of these cells through a Plk3-mediated mechanism independent from activation of the JNK signaling pathway, indicating that Plk3 plays a significant role in hypoxia-induced signaling pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Culture of Corneal Epithelial Cells—Human corneal epithelial (HCE) cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 (1:1) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 5 μg/ml insulin in an incubator supplied with 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The medium was replaced every 2 days, and cells were subcultured by treatment of cells with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA. For hypoxia experiments, confluent corneal epithelial cells were placed in an incubator supplemented with 1% O2, 5%CO2, 94% N2 at 37 °C for 4 h. For reoxygenation experiments, culture of the hypoxia-treated cells was continued for another 4 or 16 h under normal culture conditions.

Transfection—Various PLK3 kinase or its mutants, including constitutively active pEGFP-Plk3-Polo box domain (amino acids 312–652 termed pEGFP-Plk3-PBD), kinase-defective Plk3K52R (a mutant that had a substitution of lysine 52 with arginine), and kinase-defective Plk3 (EGFP-Plk3-T219E termed pEGFP-Plk3-WV) (33, 36) were transfected to human corneal epithelial cells for 16 h using a Lipofectamine-mediated method (Invitrogen). After treatment, the transfected cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis, cell survival assay, or AP-1 activity examination. Transfection of JNK1-specfic siRNA (Qiagen, cat. SI02758637) and Plk3-specific siRNA (Qiagen, cat. SI02223473) were done by adding JNK1- or Plk3-specific siRNA (a final concentration of 25 nm) and 12 μl of HiPerFect (Qiagen, cat. 301705) in 100 μl of culture medium without serum. Transfection complexes in the mixture were formed after 10 min of incubation at 22 °C. The mixture was evenly dropped into cultured cells. Transfected cells were cultured under normal growth conditions for 48–84 h before performing experiments. Control cells were transfected with nonsilencing siRNA using the same method as described above.

Cell Survival Index Determined by MTT Assays—A tetrazolium component (MTT) assay was performed following an established protocol in the laboratory (37). Briefly, a colorimetric assay system was used to measure the reduction of MTT to an insoluble formazan product by the mitochondria of viable viable cells. The culture medium was replaced with 1 ml of serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 (1:1), and 100 μl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml in PBS) were added to each well and incubated for 1 hi n a moisturized CO2 incubator. Acidic isopropyl alcohol (0.4 ml of 0.04 m HCl in absolute isopropyl alcohol) was added to dissolve the colored crystals. All samples were placed into an ELISA plate reader (Beckman DU-600 Spectrophotometer) at a wavelength of 595 nm with background subtraction. The amount of color produced, normalized with the background, is directly proportional to the number of viable cells.

Measurement of DNA Fragmentation—HCE cells were washed twice with PBS. Lysis buffer (200 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mm EDTA, 1% SDS, and 100 μg/ml proteinase-K) was added, and cells were then incubated for 4 h at 55 °C. The nuclear lysates were extracted twice with an equal volume of phenol and then extracted with an equal volume of phenolchloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). DNA was precipitated with 0.05 volume of 5 m NaCl and 2.5 volumes of absolute ethanol, incubated overnight at –20 °C, and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The DNA pellet was dried and dissolved in TE buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA) containing 20 μg/ml RNase A and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The DNA was extracted with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). DNA samples were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels, and the results were visualized by staining with 1 μg/ml ethidium bromide.

Immunocytochemistry Experiments—For Western analysis, corneal epithelial cells (2 × 105) were lysed in SDS sample buffer containing 62.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% W/V SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mm dithiothreitol, 0.01% (w/v) bromphenol blue, or phenol red. After denaturing, cell lysates were size-fractionated by PAGE. Proteins were electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. They were exposed to blocking buffer containing 5% nonfat milk in TBS-0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with the primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was applied in TBS-T buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Western blots were developed by an ECL Plus System (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and visualized by exposure of x-ray films. For immunostaining, corneal epithelial cells were grown on glass slides and treated as indicated in the figures. The cells were permeated and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies in PBS-T overnight. Slides were washed with PBS and incubated with FITC/Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG antibody. For immunoprecipitation, corneal epithelial cells (5 × 107) were rinsed with PBS, followed by incubation in 1 ml of lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 137 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm, 2 mm EDTA, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 25 mm glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin) on ice for 30 min. The cell lysates were spun at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and incubated with antibodies against Plk3 or c-Jun (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4 °C overnight. The immunocomplexes were recovered by incubation with 50 μl of 10% protein A/G-Sepharose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The immunocomplex beads were washed twice with lysis buffer and once with kinase buffer, and then, subjected to immunoblot and kinase assay. For Plk3 kinase assays, the experiments were carried out by incubation of the immunocomplex of Plk3 with GST-c-Jun fusion protein in 30 μl of kinase buffer (20 mm HEPES pH 7.6, 20 mm MgCl2, 25 mm glycerophosphate, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 20 μm ATP, and, 10 μCi of [32P]ATP) for 30 min at room temperature. Equal volumes of samples were displayed on 12% SDS-PAGE and visualized by exposure on x-ray film.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)—Nuclear proteins were extracted by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 20 min. The consensus oligonucleotide for AP-1 transcription factor (5′-CGCTTCATGAGTCAGCCGGAA-3′) was 5′-end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. DNA probes were used to hybridize with extracted nuclear proteins. Reactions were conducted by adding 1 pm γ-32P-labeled DNA probe to each sample. DNA-protein complexes were displayed by electrophoresis on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. For the supershift assay, DNA-protein complexes were further incubated with a specific antibody against c-Jun. Specific competition experiments were performed using unlabeled oligonucleotides to compete with the labeled oligonucleotides for AP-1. Nonspecific competition experiments were performed using unlabeled Sp1 oligonucleotides to interact with the labeled AP-1 oligonucleotides.

Statistical Analysis—For Western analysis, signals in the films were scanned digitally, and the optical densities (OD) were quantified with Image Calculator software. Data were shown as fractions of original values in the MTT assay or relative OD for Western blot experiments as mean ± S.E. Significant differences between the control group and treated groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance and Student's t test at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

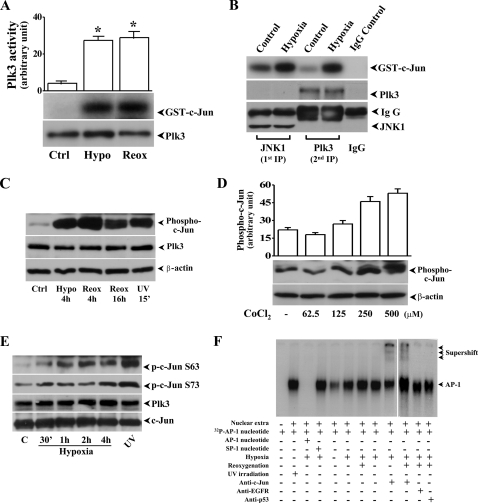

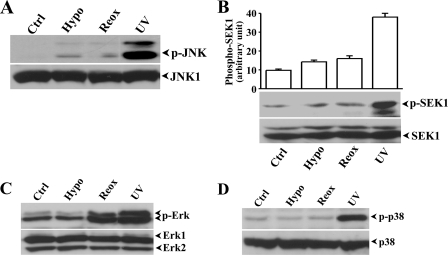

Hypoxia-induced Activation of Plk3 and c-Jun Phosphorylation—We investigated hypoxic stress-induced signaling events in hypoxia and reoxygenation-exposed HCE cells and found that hypoxic stress including hypoxia and reoxygenation elicited increased Plk3 kinase activities by detection of increased phosphorylation of c-Jun fusion protein in immunocomplex kinase assays (Fig. 1A). The specific effect of hypoxia-induced Plk3 activation on c-Jun phosphorylation was further determined by two-step immunocomplex kinase assays. In step 1, JNK-1 protein in cell lysates was removed by immunoprecipitation, and then Plk3 was further immunoprecipitated from the cell extracts in that JNK-1 protein had been depleted. The precipitated Plk3 from the extracts was used in immunocomplex kinase assays to determine the effect of hypoxia-induced Plk3 activation on phosphorylation of c-Jun fusion proteins (Fig. 1B). Results indicate that hypoxic stress activated Plk3, resulting in c-Jun protein phosphorylation in the absence of JNK activity. We also found that there were increased phosphorylation levels of the endogenous c-Jun in HCE cells exposed to hypoxia, reoxygenation, and UV irradiation (Fig. 1C). Increased phosphorylation levels of endogenous c-Jun proteins in response to hypoxic stress were mimicked by treating cells with various concentrations of CoCl2 (Fig. 1D). Hypoxic stress-induced site-specific phosphorylation of c-Jun was detected using Ser-63 and Ser-73 site-specific and antiphosphorylated c-Jun antibodies following a time course from 30 min to 4 h (Fig. 1E). We observed increased phosphorylation of c-Jun protein in both sites, while there was no change in the expression level of Plk3 during a 4-h hypoxic treatment period. The potential role of c-Jun in hypoxic stress-induced cells was further verified by detection of c-Jun activity in AP-1 complex in cell nuclei. In hypoxia- and reoxygenation-treated cells, there were increased AP-1 binding activities and supershift bands found in lanes treated with the c-Jun-specific antibody in EMSA (Fig. 1F). Control experiments were done by competing AP-1 binding with unlabeled AP-1 nucleotides and nonspecific SP-1 nucleotides and by exposure of HCE cells to UV irradiation. In addition, non-specific antibodies against epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and p53 were used in supershift experiments as the control. Previously, we reported that activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) results in phosphorylation of c-Jun protein and cellular apoptotic responses in HCE cells (38, 39). Here, we found that hypoxic stress-induced Plk3 activation phosphorylated c-Jun, suggesting that hypoxic stress may activate c-Jun through multiple pathways, such as both the Plk3 and JNK signaling pathways. We then investigated whether hypoxic stress also induced c-Jun activation through the JNK signaling pathway in corneal epithelial cells. JNK activity was determined by measuring the phosphorylation levels of JNK using the phospho-JNK specific antibody in hypoxia and reoxygenation-induced HCE cells (Fig. 2A). In a parallel control experiment, UV irradiation induced marked activation of JNK. However, there was minor activation of JNK represented by much weaker bands in hypoxic stress-induced cells. The effect of hypoxic stress on JNK activity was further verified by measuring hypoxic stress-induced activation of SEK1, an immediate upstream kinase of JNK in the kinase cascades. We found that there was a detectible and minor SEK1 phosphorylation in hypoxia/reoxygenation-exposed HCE cells (Fig. 2B). In previous studies, we demonstrate that in addition to the JNK pathway, UV irradiation can activate other MAP kinase pathways including ERK and p38 cascades. We found that Erk phosphorylation was not changed by hypoxic treatment, but the phosphorylation level was markedly increased in cells treated with hypoxia followed by reoxygenation (Fig. 2C). However, there were no significant changes in p38 activity in hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced HCE cells (Fig. 2D). These results provide supportive evidence suggesting that a novel signaling pathway, other than the JNK signaling pathway, is involved in hypoxic stress-induced c-Jun phosphorylation and AP-1 activation in HCE cells.

FIGURE 1.

Hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced activation of Plk3 and c-Jun phosphorylation in HCE Cells. A, effect of hypoxia (Hypo) and reoxygenation (Reox) on Plk3 activity. Immunocomplex kinase assays were performed to determine Plk3 kinase activity, and hypophosphorylated GST-c-Jun fusion protein was used as a substrate. B, effect of hypoxia-activated Plk3 on c-Jun phosphorylation after removing JNK. JNK protein was removed from cell lysates by immunoprecipitation, and Plk3 activity was measured by immunocomplex kinase assay. C, hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced Plk3 activation and c-Jun phosphorylation. Western blots were used to detect Plk3 expression and phosphorylated c-Jun using antibody specific to phospho-c-Jun. D, dose-dependent response of CoCl2-induced phosphorylation of c-Jun. E, time course of hypoxia-induced site-specific phosphorylation of c-Jun at Ser-63 and Ser-73. F, effect of hypoxia and reoxygenation on AP-1 DNA binding activity detected by EMSA and supershift. UV irradiation-induced phosphorylation of c-Jun and AP-1 activation were detected as positive controls.

FIGURE 2.

Hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced activation of MAP kinases. Effect of hypoxia (Hypo) and reoxygenation (Reox) on: A, JNK phosphorylation; B, SEK phosphorylation; C, Erk phosphorylation; and D, p38 phosphorylation. UV irradiation-induced MAP kinase activation served as positive controls. Activation of SEK and MAP kinases were determined by detecting hypoxia-induced changes in phosphorylation levels of these proteins with specific anti-phospho-antibodies. Statistical significance was indicated by symbols of * and ** for p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively.

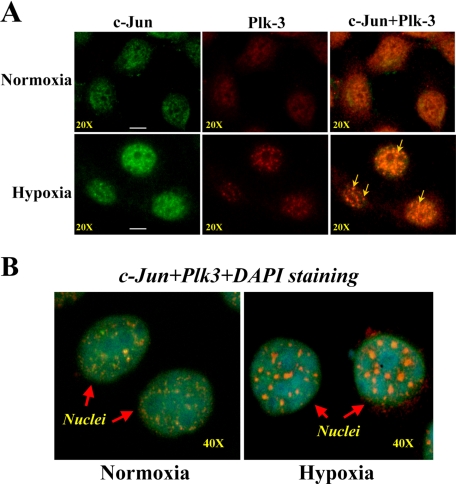

Hypoxia-induced Nuclear Co-localization of Plk3 with c-Jun—Hypoxic stress-induced activation of Plk3 phosphorylated c-Jun fusion protein in vitro, suggesting that c-Jun may be a downstream target protein for Plk3 in the hypoxia-induced signaling pathway in HCE cells. To verify the interaction between Plk3 and c-Jun in the hypoxia-induced pathway, we examined the potential co-localization of Plk3 and c-Jun in subcellular compartments. Immunostaining experiments were performed to map the protein locations of Plk3 and c-Jun in hypoxia-induced HCE cells. Data obtained from double immunostaining and immunofluorescent microscopy showed that there were significant changes in immunoactivities by forming dense regions that were co-localized in the nuclear region of hypoxia-induced cells. In contrast, Plk3 was observed mainly in the surrounding region of nuclei without overlapped immunoactivities with c-Jun in control cells (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, hypoxia-induced Plk3 and c-Jun activities were co-localized in cell nuclei, indicated by DAPI staining and double immunostaining (Fig. 3B). The results of immunostaining experiments indicate hypoxic stress-induced changes of Plk3 in subcellular compartments and suggest interactions between Plk3 and c-Jun in cell nuclei.

FIGURE 3.

Immunocolocalization of Plk3 and c-Jun. A, co-localization of Plk3 and c-Jun in hypoxia-induced cells. B, co-localization of Plk3 and c-Jun in nuclei. Cellular Plk3 and c-Jun proteins in control and hypoxia-induced HCE cell were stained using monoclonal antibodies specific to Plk3 and c-Jun, respectively. Cell nuclei were stained by DAPI.

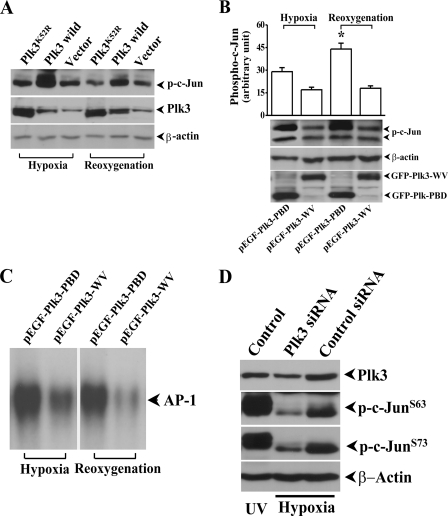

Activation of AP-1 by Hypoxia-induced Plk3 Activation—Although Plk3 and c-Jun were co-localized in hypoxia-induced cell nuclei, it is important to know whether Plk3 is functionally associated with c-Jun activation in response to hypoxic stress. We transfected HCE cells with wild-type Plk3 (Plk3wild) using lipofection and found that overexpression of Plk3 effectively increased the level of hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced c-Jun phosphorylation (Fig. 4A). However, transfection of HCE cells with a kinase-defective Plk3 mutant (Plk3K52R) and the control vector did not affect hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced c-Jun phosphorylation in HCE cells. Next, the affect of hypoxia/reoxygenation on c-Jun activity was studied in HCE cells transfected with constitutively active Plk3-PBD and defective Plk3-WV, respectively. 20-h post-transfection, cells were first analyzed for expression of GFP-tagged Plk3 mutants, and then the changes of c-Jun phosphorylation in transfected cells were determined by Western analysis using an antibody against phosphorylated c-Jun (Fig. 4B). It appeared that there was a much higher level of hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced c-Jun phosphorylation in HCE cells transfected with constitutively active Plk3-PBD than those defective Plk3-WV-transfected cells. Further downstream, hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced AP-1 DNA binding activity in EMSA was markedly increased in Plk3-PBD transfected HCE cells compared with those cells transfected with Plk3-WV (Fig. 4C). In addition, hypoxic stress induced a much lower phosphorylation level of c-Jun at both Ser-63 and Ser-73 sites in cells where Plk3 mRNA was knocked-down by transfecting the cell with Plk3-specific siRNA (Fig. 4D). These results strongly support the initial observation that hypoxic stress-induced Plk3 activation results in increases in c-Jun phosphorylation and AP-1 activation.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of Plk3 mutants on c-Jun phosphorylation and AP-1 activation. A, effect of overexpressing wild-type Plk3 and kinase-defective Plk3 mutant (Plk3K52R) on c-Jun phosphorylation. B, effect of overexpressing constitutively active Plk3 (Plk3-PBD) and defective Plk3 (Plk3-WV) on c-Jun phosphorylation. C, effect of overexpressing constitutively active Plk3 (Plk3-PBD) and defective Plk3 (Plk3-WV) on AP-1 activation detected by EMSA. Control experiments were performed by transfecting HCE cells with GFP-tagged Plk3 and the vector only. D, effect of knocking-down Plk3 using siRNA on hypoxia-induced c-Jun phosphorylation. UV irradiation-induced c-Jun phosphorylation served as positive controls. The symbol * indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05, n = 3).

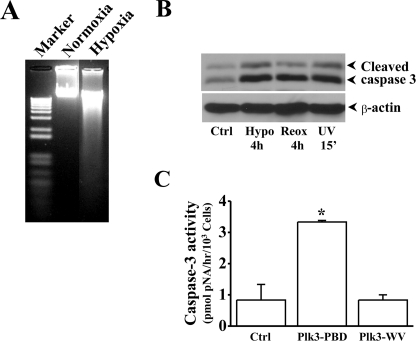

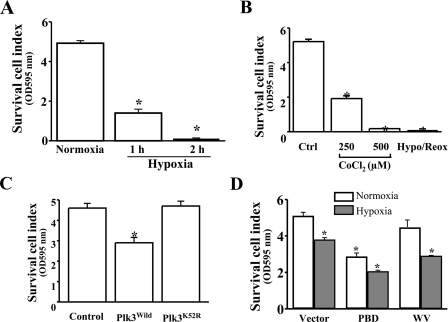

Mediation of Hypoxic Stress-induced Apoptosis by Plk3—We demonstrated that Plk3 was rapidly activated in response to hypoxic stress, resulting in c-Jun/AP-1 activation. Previously, we have shown that activation of c-Jun/AP-1 by UV irradiation is associated with apoptosis in HCE cells. To investigate the effect of hypoxic stress on apoptosis, HCE cells were induced by hypoxia in the presence of 1% O2 in cultures. There was significantly increased apoptosis in hypoxia-induced cells, determined by measuring DNA fragmentation and caspase 3 activation, respectively (Fig. 5, A and B). The effect of Plk3 activity on apoptosis was observed in HCE cells transfected with the constitutively active Plk3-PBD and defective Plk3-WV. There were significantly increased caspase 3 activities observed in cells overexpressing constitutively active Plk3, suggesting that Plk3 activity is associated in triggering apoptosis in these cells (Fig. 5C). To further verify the effect of hypoxic stress-induced Plk3 activation on cell death, cell viabilities were also determined by MTT assays (Fig. 6). Survival cell index of hypoxia-induced cells were significantly suppressed within 1 h and continuously decreased to a very low level in 2 h (Fig. 6A). In the other group experiments, CoCl2 (250–500 μm) was applied to HCE cells to mimic hypoxic stress. Consistent with the observation in hypoxia-induced cells, CoCl2 treatment induced decreases in survival cell index to very low levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). To investigate the effect of Plk3 on cell viability, HCE cells were transfected with the wild-type Plk3 (Plk3wild) and kinase-defective Plk3 mutant (Plk3K52R). Overexpression of Plk3wild induced a significant decrease in survival cell index (Fig. 6C). However, transfection of cells with Plk3K52R had no affect on the cell viability compared with control cells. The effect of Plk3 activity on hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced decreases in cell viability was studied in cells transfected with the constitutively active Plk3 (pEGFP-Plk3-PBD) and defective Plk3 (pEGFP-Plk3-WV). Survival cell index was significantly decreased in constitutively active Plk3-transfected HCE cells compared with control (normoxia) cells that were transfected with defective Plk3 mutants and the vector (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that Plk3 activation by hypoxia/reoxygenation plays an important role in hypoxic stress-induced apoptotic responses in HCE cells.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of Plk3 on hypoxia-induced apoptosis. A, detection of hypoxia-induced DNA fragmentation. B, activation of caspase 3 induced by hypoxia and reoxygenation. UV irradiation-induced caspase 3 activation served as the positive control. C, effect of overexpressing constitutively active Plk3 (Plk3-PBD) and defective Plk3 (Plk3-WV) on caspase 3 activation. The symbol * indicates a significant difference (p < 0.01, n = 4).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of Plk3 on hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced changes in survival cell index detected by MTT assay. A, hypoxia-induced decrease in survival cell index. B, CoCl2 induced a decrease in survival cell index. C, effect of overexpressing wild-type Plk3 and kinase-defective Plk3 mutant (Plk3K52R) on survival cell index. D, effect of overexpressing constitutively active Plk3 (Plk3-PBD) and defective Plk3 (Plk3-WV) on hypoxia-induced survival cell index. The symbol * indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05, n = 4).

DISCUSSION

As a member of a proto-oncogene family, c-Jun involves formation of AP-1 transcription factor dimers with other members in the Jun, Fos, and ATF families. Activity of c-Jun is upregulated by growth factors, cytokines, and UV irradiation (35, 40–42). It has been known that c-Jun is the downstream target protein and substrate of JNK in response to cytokine and environmental stress stimulation. We found that both SEK-1 and JNK are slightly activated by hypoxia/reoxygenation, while c-Jun is strongly phosphorylated by hypoxia/reoxygenation in HCE cells (Fig. 2, A and B). This is opposite to UV irradiation-induced cells in that both JNK and c-Jun were highly phosphorylated, suggesting that there should be other protein kinases involving hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced phosphorylation of c-Jun. In HCE cells, Western analysis using the anti-phospho-p38 antibody demonstrated that there is no p38 activation after exposing the cells to hypoxia/reoxygenation, suggesting that the p38 signaling pathway may not play a main role in hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced AP1 activation. However, it seems that the Erk signaling pathway is involved in the reoxygenation-induced response, because the phosphorylation level of Erk is increased only in the reoxygenation process (Fig. 2C). Our data in measuring MAP kinase pathways in hypoxic stress-induced HCE cells provide additional information to support the initial hypothesis that there may be another signaling mechanism involving hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced phosphorylation of c-Jun in these cells.

Plk3 is a multifunctional protein kinase that is activated in response to various environment stresses (27). The effect of hypoxia/reoxygenation on Plk3 activation has not been previously reported in the published literature. In this study, our results revealed, for the first time, that Plk3 is activated by hypoxia/reoxygenation, and that active Plk3 phosphorylates c-Jun protein, resulting in a decreasing survival cell index and increasing cell apoptosis. We previously reported that, in addition to JNK activation, Plk3 was in parallel activated by UV irradiation stress, resulting in c-Jun phosphorylation (35). In this case, it is very likely that Plk3 also plays a role in hypoxic stress-induced c-Jun phosphorylation. The results of this study demonstrate that Plk3 is indeed activated by hypoxia/reoxygenation, and active Plk3 directly phosphorylates c-Jun protein as its substrate. Further evidence indicates that hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced c-Jun phosphorylation is significantly enhanced by overexpression of wild-type or constitutively active Plk3 in HCE cells (Fig. 4). In contrast, knocking-down Plk3 mRNA to suppress Plk3 expression had a profound effect on Jun phosphorylation at both Ser-63 and Ser-73 residues, suggesting that there may be other mechanisms involved in the hypoxia-induced signaling. Details about this requires further investigation. As expected, AP1 activity is also greatly increased by overexpression of wild-type or constitutively active Plk3. These results indicate that Plk3 plays a major role in hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced c-Jun activation. The question remaining to be answered in our future research is how hypoxia/reoxygenation activates Plk3. It has been shown that ATM/ATR is activated by hypoxia and reoxygenation. In response to DNA damage, activated ATM/ATR induced Chk1 and Chk2 activation, which then activated Plk3. We found Chk1 and Chk2 were phosphorylated by hypoxia stress (data not shown). It is very possible that hypoxia and reoxygenation activate ATM/ATR-Chk1/Chk2, thus leading to Plk3 activation.

There is no doubt that our findings in the present study provide important evidence establishing that hypoxia/reoxygenation-activated Plk3 plays a critical role in mediating c-Jun activation. On the other hand, transfection of Plk3-PBD, but not its mutants, causes significant activation of c-Jun, which correlates with enhanced capspase-3 activity. Given that PBD is known to function as a motif interacting with serine/threonine-phosphorylated residues (43), it is also possible that Plk3-PBD specifically recognizes and interacts with phosphorylated/activated c-Jun. We observed that Hif1 expression increased with hypoxia treatment (data not show), indicating that the hypoxia condition is successful or proven. Whether Hif1 affects Plk3-mediated c-Jun activation was not researched in this study; however, the time course of c-Jun phosphorylation was shown to be consistent with the time course of Hif1 activation from 0.5 to 4 h under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1D). It seems that posttranslational regulation is dominant in c-Jun activation. The correlation between hypoxic stress-induced Plk3 and c-Jun activation is evidenced by direct phosphorylation of c-Jun protein by active Plk3 and using immunostaining to co-localize active Plk3 and c-Jun in the nuclei of HCE cells after hypoxic stimulation (Fig. 3). Finally, interaction between Plk3 and c-Jun in response to hypoxic stress stimulation has functional meaning because: 1) increased Plk3 activity parallels increased c-Jun phosphorylation in response to hypoxic stress; 2) hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis is affected by excessive Plk3 activity in exogenous Plk3-transfected cells; and 3) the effect of hypoxic stress-induced Plk3 activation on apoptosis is enhanced by transfecting cells with wild type and constitutively active Plk3. Hypoxia and reoxygenation cause major damage to human organs and various cells types, including cancer cells. In fact, hypoxia can be found in many disease stages and is considered to be one of the stress stimuli that induces cellular responses directly related to cellular function and apoptosis. Thus, to study the effect of hypoxic stress on cellular signaling pathways is of clinical importance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants EY12953 (to L. L.) and CA074229 (to W. D.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ROS, reactive oxygen species; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; GST, glutathione S-transferase; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GFP, green fluorescent protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; Plk3, Polo-like-kinase 3; Hif, hypoxia-inducible factor; MAP, mitogen-activated protein.

References

- 1.Singh, N., Amin, S., Richter, E., Rashid, S., Scoglietti, V., Jani, P. D., Wang, J., Kaur, R., Ambati, J., Dong, Z., and Ambati, B. K. (2005) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46 1647–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh, N., Jani, P. D., Suthar, T., Amin, S., and Ambati, B. K. (2006) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47 4787–4793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cursiefen, C., Maruyama, K., Jackson, D. G., Streilein, J. W., and Kruse, F. E. (2006) Cornea 25 443–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mwaikambo, B. R., Sennlaub, F., Ong, H., Chemtob, S., and Hardy, P. (2006) Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47 4356–4364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang, M. C., Wang, Y., and Yang, Y. (2006) Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 14 359–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond, E. M., Denko, N. C., Dorie, M. J., Abraham, R. T., and Giaccia, A. J. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 1834–1843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou, B. B., and Elledge, S. J. (2000) Nature 408 433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruick, R. K., and McKnight, S. L. (2001) Science 294 1337–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appelhoff, R. J., Tian, Y. M., Raval, R. R., Turley, H., Harris, A. L., Pugh, C. W., Ratcliffe, P. J., and Gleadle, J. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 38458–38465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahams, P. J., Schouten, R., van Laar, T., Houweling, A., Terleth, C., and van der Eb, A. J. (1995) Mutat. Res. 336 169–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smirnova, I. S., Yakovleva, T. K., Rosanov, Y. M., Aksenov, N. D., and Pospelova, T. V. (2001) Cell Biol. Int. 25 1101–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bindra, R. S., Schaffer, P. J., Meng, A., Woo, J., Maseide, K., Roth, M. E., Lizardi, P., Hedley, D. W., Bristow, R. G., and Glazer, P. M. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 8504–8518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budanov, A. V., Shoshani, T., Faerman, A., Zelin, E., Kamer, I., Kalinski, H., Gorodin, S., Fishman, A., Chajut, A., Einat, P., Skaliter, R., Gudkov, A. V., Chumakov, P. M., and Feinstein, E. (2002) Oncogene 21 6017–6031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comerford, K. M., Cummins, E. P., and Taylor, C. T. (2004) Cancer Res. 64 9057–9061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dougherty, C. J., Kubasiak, L. A., Frazier, D. P., Li, H., Xiong, W. C., Bishopric, N. H., and Webster, K. A. (2004) Faseb J. 18 1060–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, H., Ma, Y., Pagliari, L. J., Perlman, H., Yu, C., Lin, A., and Pope, R. M. (2004) J. Immunol. 172 1907–1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCloskey, C. A., Kameneva, M. V., Uryash, A., Gallo, D. J., and Billiar, T. R. (2004) Shock 22 380–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laderoute, K. R., Calaoagan, J. M., Gustafson-Brown, C., Knapp, A. M., Li, G. C., Mendonca, H. L., Ryan, H. E., Wang, Z., and Johnson, R. S. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 2515–2523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishi, H., Nishi, K. H., and Johnson, A. C. (2002) Cancer Res. 62 827–834 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laderoute, K. R., Calaoagan, J. M., Knapp, M., and Johnson, R. S. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 4128–4137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seagroves, T. N., Ryan, H. E., Lu, H., Wouters, B. G., Knapp, M., Thibault, P., Laderoute, K., and Johnson, R. S. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 3436–3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donohue, P. J., Alberts, G. F., Guo, Y., and Winkles, J. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 10351–10357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamanaka, R., Smith, M. R., O'Connor, P. M., Maloid, S., Mihalic, K., Spivak, J. L., Longo, D. L., and Ferris, D. K. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 21086–21091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, B., Ouyang, B., Pan, H., Reissmann, P. T., Slamon, D. J., Arceci, R., Lu, L., and Dai, W. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 19402–19408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, W., Lu, L., Wang, Z., Wang, L., Fung, J. J., Thomson, A. W., and Qian, S. (2001) Transplantation 72 1423–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simmons, D. L., Neel, B. G., Stevens, R., Evett, G., and Erikson, R. L. (1992) Mol. Cell. Biol. 12 4164–4169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai, W. (2005) Oncogene 24 214–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bahassi el, M., Conn, C. W., Myer, D. L., Hennigan, R. F., McGowan, C. H., Sanchez, Y., and Stambrook, P. J. (2002) Oncogene 21 6633–6640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie, S., Wu, H., Wang, Q., Cogswell, J. P., Husain, I., Conn, C., Stambrook, P., Jhanwar-Uniyal, M., and Dai, W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 43305–43312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie, S., Wu, H., Wang, Q., Kunicki, J., Thomas, R. O., Hollingsworth, R. E., Cogswell, J., and Dai, W. (2002) Cell Cycle 1 424–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouyang, B., Pan, H., Lu, L., Li, J., Stambrook, P., Li, B., and Dai, W. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 28646–28651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conn, C. W., Hennigan, R. F., Dai, W., Sanchez, Y., and Stambrook, P. J. (2000) Cancer Res. 60 6826–6831 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, Q., Xie, S., Chen, J., Fukasawa, K., Naik, U., Traganos, F., Darzynkiewicz, Z., Jhanwar-Uniyal, M., and Dai, W. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 3450–3459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruan, Y. W., Ling, G. Y., Zhang, J. L., and Xu, Z. C. (2003) Brain Res. 982 228–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, L., Dai, W., and Lu, L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 32121–32127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang, N., Wang, X., Jhanwar-Uniyal, M., Darzynkiewicz, Z., and Dai, W. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 10577–10582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, T., and Lu, L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 12988–91295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, L., Xu, D., Dai, W., and Lu, L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 3678–3685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu, L., Wang, L., and Shell, B. (2003) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44 5102–5109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karin, M., Liu, Z., and Zandi, E. (1997) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9 240–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, T., Dai, W., and Lu, L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 32668–32676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou, H., Gao, J., Lu, Z. Y., Lu, L., Dai, W., and Xu, M. (2007) Cell Prolif. 40 431–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elia, A. E., Rellos, P., Haire, L. F., Chao, J. W., Ivins, F. J., Hoepker, K., Mohammad, D., Cantley, L. C., Smerdon, S. J., and Yaffe, M. B. (2003) Cell 115 83–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]