Abstract

Champagne coat color in horses is controlled by a single, autosomal-dominant gene (CH). The phenotype produced by this gene is valued by many horse breeders, but can be difficult to distinguish from the effect produced by the Cream coat color dilution gene (CR). Three sires and their families segregating for CH were tested by genome scanning with microsatellite markers. The CH gene was mapped within a 6 cM region on horse chromosome 14 (LOD = 11.74 for θ = 0.00). Four candidate genes were identified within the region, namely SPARC [Secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich (osteonectin)], SLC36A1 (Solute Carrier 36 family A1), SLC36A2 (Solute Carrier 36 family A2), and SLC36A3 (Solute Carrier 36 family A3). SLC36A3 was not expressed in skin tissue and therefore not considered further. The other three genes were sequenced in homozygotes for CH and homozygotes for the absence of the dilution allele (ch). SLC36A1 had a nucleotide substitution in exon 2 for horses with the champagne phenotype, which resulted in a transition from a threonine amino acid to an arginine amino acid (T63R). The association of the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) with the champagne dilution phenotype was complete, as determined by the presence of the nucleotide variant among all 85 horses with the champagne dilution phenotype and its absence among all 97 horses without the champagne phenotype. This is the first description of a phenotype associated with the SLC36A1 gene.

Author Summary

The purpose of this study was to uncover the molecular basis for the champagne hair color dilution phenotype in horses. Here, we report a DNA base substitution in the second exon of the horse gene SLC36A1 that changes an amino acid in the transmembrane domain of the protein from threonine to arginine. The phenotypic effect of this base change is a diminution of hair and skin color intensity for both red and black pigment in horses, and the resulting dilution has become known as champagne. This is the first genetic variant reported for SLC36A1 and the first evidence for its effect on eye, skin, and hair pigmentation. So far, no other phenotypic effects have been attributed to this gene. This discovery of the base substitution provides a molecular test for horse breeders to test their animals for the Champagne gene (CH).

Introduction

Many horse breeders value animals with variation in coat color. Several genes are known which diminish the intensity of the coloration and are phenotypically described as “dilutions”. Two of these are a result of the Cream (CR) locus and Silver (Z) locus. The molecular basis for Cream is the result of a single base change in exon 2 of the SLC45A2 (Solute Carrier 45 family A2, aka MATP for membrane associated transport protein) on ECA21 [1],[3]. This change results in the replacement of a polar acidic aspartate with a polar neutral asparagine in a putative transmembrane region of the protein coded for by this gene [3],[2]. CR has an incompletely dominant mode of expression. Heterozygosity for CR dilutes only pheomelanin (red pigment) whereas homozygosity for CR results in extreme dilution of both pheomelanin and eumelanin (black pigment) [4].

The Silver dilution is the result of a missense mutation of PMEL17 (Premelanosomal Protein) on ECA6. The base change causes replacement of a cytosolic polar neutral arginine with non-polar neutral cysteine in PMEL17 [2]. In contrast to CR, the Z locus is fully dominant and affects only eumelanin causing little to no visible change in the amount of pheomelanin regardless of zygosity. The change in eumelanin is most apparent in the mane and tail where the black base color is diluted to white and gray [5].

The coat color produced by the CH locus is similar to that of the CR locus in that both can cause dilution phenotypes affecting pheomelanin and eumelanin. However, the effect of CH differs from CR in that; 1) CH dilutes both pheomelanin and eumelanin in its heterozygous form and 2) heterozygotes and homozygotes for CH are phenotypically difficult to distinguish. The homozygote may differ by having less mottling or a slightly lighter hair color than the heterozygote. Figure 1 displays images of horses with the three base coat colors chestnut, bay and black and the effect of CH upon each. Figure 2 shows that champagne foals are born with blue eyes, which change color to amber, green, or light brown and pink “pumpkin skin which acquires a darker mottled complexion around the eyes, muzzle, and genitalia as the animal matures [6]. Foals with one copy of CR also have pink skin at birth but their skin is slightly darker and becomes black/near black with age. The champagne phenotype is found among horses of several breeds, including Tennessee Walking Horses and Quarter Horses. Here we describe family studies that led to mapping the gene and subsequent investigations leading to the identification of a genetic variant that appears to be responsible for the champagne dilution phenotype.

Figure 1. Effect of Champagne gene action on base coat colors of horses (chestnut, bay, and black).

A) Chestnut – horse only produces red pigment. B) Chestnut diluted by Champagne = Gold Champagne. C) Bay – black pigment is limited to the points (e.g. mane, tail, and legs) allowing red pigment produced on the body to show. D) Bay diluted by Champagne = Amber Champagne. E) Black – red and black pigment produced, red masked by black. F) Black diluted by Champagne = Classic Champagne.

Figure 2. Champagne Eye and Skin traits.

A, B and C) Eye and skin color of foals. D and E) Eye color and skin mottling of adult horse.

Results

Linkage Analyses

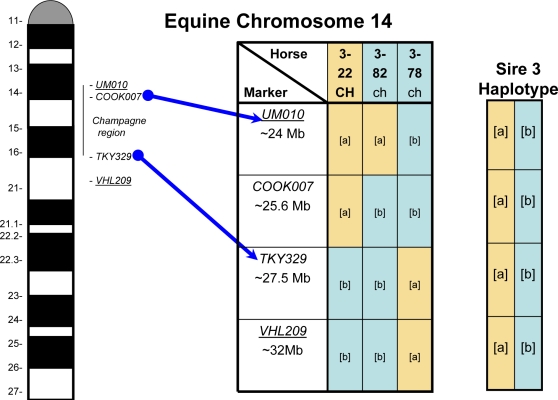

Table 1 summarizes the evidence for linkage of the CH gene to a region of ECA14. The linkage phase for each family was apparent based on the number of informative offspring in each family. Recombination rates (θ) were based on the combined recombination rate from all families. Four microsatellites showed significant linkage to the CH locus: VHL209 (LOD = 6.03 for θ = 0.14), TKY329 (LOD = 3.64 for θ = 0.10), UM010 (LOD = 5.41 for θ = 0.04) and COOK007 (LOD = 11.74 for θ = 0.00).

Table 1. Linkage Analysis between the Champagne Dilution and Microsatellite Markers; UM010, COOK007, TKY329 and VHL209.

| alleles | Sire contribution | Statistics | ||||||||

| Sire Family | (CH) | microsatellite | a/b | N | a+ | a− | b+ | b− | LOD score | Θ |

| 3 | (+/−) | UM010 | 124/108 | 23 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 5.41 | |

| Σ = | 5.41 | 0 | ||||||||

| 1 | (+/−) | COOK007 | 332/334 | 14 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4.21 | |

| 2 | (+/−) | COOK007 | 332/334 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.41 | |

| 3 | (+/−) | COOK007 | 332/324 | 17 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 5.12 | |

| Σ = | 11.74 | 0 | ||||||||

| 1 | (+/−) | TKY329 | 117/139 | 15 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1.92 | |

| 2 | (+/−) | TKY329 | 111/137 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1.34 | |

| 3 | (+/−) | TKY329 | 117/139 | 18 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 3.64 | |

| Σ = | 6.9 | 0.1 | ||||||||

| 1 | (+/−) | VHL209 | 95/93 | 13 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1.49 | |

| 2 | (+/−) | VHL209 | 91/93 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0.46 | |

| 3 | (+/−) | VHL209 | 95/93 | 24 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 4.08 | |

| Σ = | 6.03 | 0.14 | ||||||||

N = the number of informative meiosis.

Θ = recombination frequency between that microsatelite and the champagne gene for all families combined.

Σ = LOD score for which 1/10Σ = the odds the association between the phenotype and the marker is due to chance.

Figure 3 identifies the haplotypes for offspring of a single sire showing recombination between the genetic markers and the CH locus. Pedigrees of the three sire families and haplotype information are provided in Figure S1 and Table S1 respectively. The CH locus maps to an interval between UM010 and TKY329 with microsatellite. No recombinants were detected among 39 informative offspring between the CH and COOK007 locus.

Figure 3. Example of Recombinant Haplotypes.

Linear relationship from top to bottom between the microsatellites, phenotype, and genotype of recombinant offspring for study sire #3. Phenotype is noted in top row with offspring's ID #.

Candidate Genes

Candidate genes were selected on the basis of proximity to the marker COOK007 and as genes previously characterized in other species as influential in the production or migration of pigment cells.

SPARC was located closest at ∼90 kb downstream from COOK007 and is coded for on the plus strand of DNA. It has been implicated in migration of retinal pigment epithelial cells in mice [7].

SLC36A family members are solute carriers and other solute carrier families have been found to play a role in coat color. SLC36A1 is located ∼250 kb downstream from COOK007. It is the first and most proximal to COOK007 of three genes in this family and is coded for on the minus strand of DNA.

SLC36A2 and SLC36A3 are coded for on the plus strand of DNA and are approximately 350 k and 380 k downstream from COOK007 respectively. A2 and A3 have been found to be expressed in a limited range of tissues in humans and mice [8].

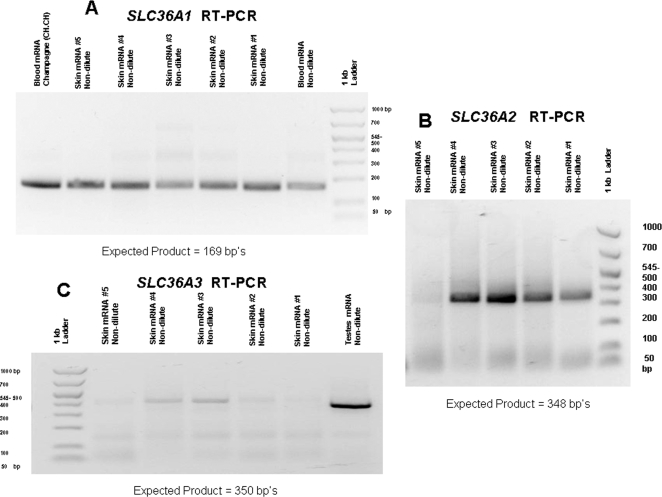

RT-PCR

RT-PCR (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction) was used to determine if SLC36A1, SLC36A2 or SLC36A3 were expressed in skin. SLC36A1 and SLC36A2 were expressed in skin and their genomic exons were sequenced. SLC36A3 was not detected in skin and therefore not investigated for detection of SNPs. Results for RT-PCR of these three genes are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. RT-PCR product results for SLC36A1, A2 and A3.

A) RT-PCR results for SLC36A1. B) RT-PCR results for SLC36A2. C) RT-PCR results for SLC36A3. (Faint bands observed above 400 bp on gel C were sequenced and did not show homology to SLC36A3.)

Sequencing

All 9 exons of SPARC were sequenced. Three SNPs were found in exons but none showed associations with the champagne phenotype and are shown in Table S2.

SLC36A2 was sequenced with discovery of 9 SNPs in exons. None of the SNPs showed associations with CH. These SNPs and all other variations detected are described in Table S2.

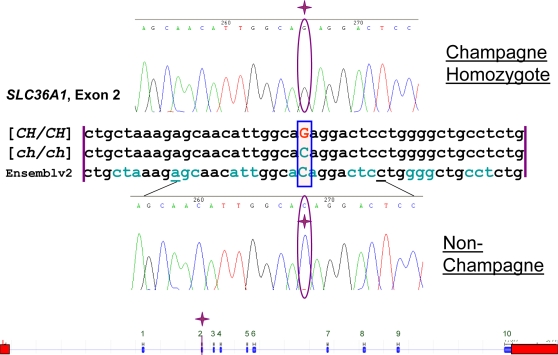

SLC36A1 was sequenced. Only one SNP was found, a missense mutation involving a single nucleotide change from a C to a G at base 76 of exon 2 (c.188C>G) (Figure 5). These SLC36A1 alleles were designated c.188[C/G], where c.188 designates the base pair location of the SNP from the first base of SLC36A1 cDNA, exon 1. Sequencing traces for the partial coding sequence of SLC36A1 exon 2 with part of the flanking intronic regions for one non-champagne horse and one champagne horse were deposited in GenBank with the following accession numbers respectively: EU432176 and EU432177. This single base change at c.188 was predicted to cause a transition from a threonine to arginine at amino acid 63 of the protein (T63R).

Figure 5. Sequence Alignment and Gene Diagram.

Alignment is between homozygous champagne, non-dilute, and horse genome assembly. Reading frame is marked by alternating colors of codons. Bottom is diagram of SLC36A1 with the identified SNP in exon 2. Sequence and gene layout have been verified on Ensembl genome browser equine assembly v2. Blue blocks of gene layout are exons and red boxes are the 5′ and 3′ UTRs.

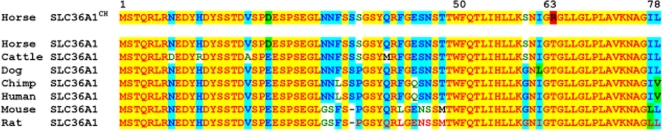

Protein Alignment

Figure 6 shows the alignment of the protein sequence for exons 1 and 2 of SLC36A1 for seven mammalian species with sequence information from Genbank (horse, cattle, chimpanzee, human, dog, rat and mouse). Alignment was performed using AllignX function of Vector NTI Advance 10 (Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, California). The alignment demonstrates that this region is highly conserved among all species. At position 63, the amino acid sequence is completely conserved among these species, with the exception of horses possessing the champagne phenotype. This replacement of threonine with arginine occurs in a putative transmembrane domain of the protein [9].

Figure 6. Seven Species Protein Sequence Alignment for SLC36A1 exons 1 and 2.

The R highlighted in red is the amino acid replacement associated with the champagne phenotype.

Population Data

The distribution of c.188G allele among different horse breeds and among horses with and without the champagne phenotype was investigated. Table 2 is a compilation of the population data collected via the genotyping assay. All dilute horses (85) which did not have the CR gene, tested positive for the c.188G allele with genotypes c.188C/G or c.188G/G. No horses in the non-dilute control group (97) possessed the c.188G allele. The horses used for the population study were selected for coat color and not by random selection; therefore measures of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium are not applicable and were not calculated.

Table 2. Genotyping Results for c.188(C/G) locus.

| Champagne (CH/CH or CH/ch) | Non-Dilute (ch/ch, cr/cr) | |||

| Horse Breeds | G/G | G/C | C/C | Total |

| American Cream Draft Cross | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| American Miniature Horse | 0 | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| American Quarter Horse | 1 | 26 | 1 | 28 |

| American Paint Horse | 0 | 13 | 32 | 45 |

| American Saddlebred | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Appaloosa | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Kentucky Mountain | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Part Arabian | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Pinto | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Pony | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Missouri Foxtrotter | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Mule | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Spanish Mustang | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Spotted Saddle Horse | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Tennessee Walking Horse | 3 | 17 | 20 | 40 |

| Thoroughbred | 0 | 0 | 35 | 35 |

| Total | 4 | 82 | 97 | 183 |

Discussion

Family studies clearly showed linkage of the gene for the champagne dilution phenotype within a 6 cM region on ECA14 [10] (Table 1). Based on the Equine Genome Assembly V2 as viewed in ENSEMBL genome browser (http://www.ensembl.org/Equus_caballus/index.html) this region spans approximately 2.86 Mbp [11]. Within that region, four candidate genes were investigated; one based on known effects on melanocytes (eg. SPARC) and three for their similarity to other genes previously shown to influence pigmentation (eg, SLC36A1, A2, and A3). While SNPs were found within the exons of SPARC, none were associated with CH. Of the other 3 candidate genes, only SLC36A1 and SLC36A2 were found to be expressed in skin cells. Therefore, the exons of those two genes were sequenced. A missense mutation in the second exon of SLC36A1 showed complete association with the champagne phenotype across several breeds. While SNPs were found for SLC36A2, none showed associations at the population level for the champagne dilution phenotype.

This observation is the first demonstration for a role of SLC36A1 in pigmentation. Orthologous genes in other species are known to affect pigmentation. For example, the gene responsible for the cream dilution phenotypes in horses, SLC45A2 (MATP), belongs to a similar solute carrier family. In humans, variants in SLC45A2 have been associated with skin color variation [12] and a similar missense mutation (p.Ala111Thr) in SLC24A5 (a member of potassium-dependent sodium-calcium exchanger family) is implicated in dilute skin colors caused from decreased melanin content among people of European ancestry [13]. The same gene, SLC24A5 is responsible for the Golden (gol) dilution as mentioned in the review of mouse pigment research by Hoekstra (2006) [14]

It is proposed, here, that the missense mutation in exon 2 of SLC36A1 is the molecular basis for champagne dilution phenotype. While this study provides evidence that this is the mutation responsible for the champagne phenotype, the proof is of a statistical nature and a non-coding causative mutation can not be ruled out at this point. SLC36A1, previously referred to by the name PAT1 (proton/amino acid transporter 1) in human and mouse [15], is a proton coupled small amino acid transporter located and most active in the brush border membranes of intestinal epithelial cells. This protein has also been characterized in rats under the name LYAAT1 (lysosomal amino acid transporter 1). LYAAT1 is localized in the membrane of lysozomes in association with LAMP1 (lysosomal associated protein 1) and in the cell membrane of post-synaptic junctions. In lysozomes it allows outward transport of protons and amino acids from the lysozome to the cytosol [16]. During purification and separation of early-stage melanosomes LAMP1 is found in high concentrations in the fraction containing stage II melanosomes [17],. Perhaps SLC36A1 plays a role in transitions from lysozome-like precursor to melanosome. Since organellular pH affects tyrosine processing and sorting [18], an amino acid substitution in this protein may affect pH of the early stage melanosome and the ability to process tyrosine properly. There must be an increase in pH, before the tyrosinase can be activated. The cytosolic pH gradient must also be maintained for proper sorting and delivery of the other proteins required for melanosome development [19]. Thus, the pH gradient of the cell may be altered by this mutation.

This variant, discovered in association with a coat dilution in the horse, is the first reported for the SLC36A1 gene. The phenotype resulting from this mutation, a reduction of pigmentation in the eyes, skin and hair, illustrates previously unknown functions of the protein product of SLC36A1. Furthermore, now that a molecular test for champagne dilution is established, the genotyping assay can be used in concert with available tests for cream dilution and silver dilution to clarify the genetic basis of a horse's dilution phenotype. This will give breeders a new tool to use in developing their breeding programs whether they desire to breed for these dilutions or to select against them.

Materials and Methods

Horses

Three half-sibling families, designated 1, 2 and 3, were used for mapping studies. Family 1 consisted of a Tennessee Walking Horse (TWH) stallion, known heterozygous at the Champagne locus (CH/ch), and his 17 offspring out of non-dilute mares (ch/ch). Family 2 consisted of an American Paint Horse stallion (CH/ch) and his 10 offspring out of non-dilute (ch/ch) mares. Family 3 consisted of a TWH stallion (CH/ch), 23 offspring and their 12 non-dilute dams (ch/ch) and 1 dilute (buckskin) dam (ch/ch, CR/cr).

To investigate the distribution of the gene among dilute and non-dilute horses of different horse breeds, 97 non-champagne horses were chosen from stocks previously collected and archived at the MH Gluck Equine Research Center. These horses were from the following breeds: TWH (20), Thoroughbreds (TB, 35), American Paint Horses (APHA, 32), Pintos (5), American Saddlebreds (ASB, 2), one American Quarter Horse (AQHA), one pony, and one American Miniature (AMH) Horse.

Hair and blood samples from horses with the champagne dilution phenotype were submitted by owners along with pedigree information and photographs showing the champagne color and characteristics of each horse. Samples were collected from the following breeds (85 total): American Miniature Horse (9), American Cream Draft cross (1), American Quarter Horse (27), American Paint Horse (13, in addition to the family), American Saddlebred (2), Appaloosa (1), ASB/Friesian cross (1), Arabian crossed with APHA or AQHA horses (3), Missouri Foxtrotter(4), Mule (2), Pony (1), Spanish Mustang 1), Spotted Saddle Horse (1), Tennessee Walking Horse (20, in addition to the families).

Color Determination

To be characterized as possessing the champagne phenotype, horses exhibited a diminished intensity of color (dilution) in black or brown hair pigment and met at least two of the three following criteria: 1) mottled skin around eyes, muzzle and/or genitalia, 2) amber, green, or light brown eyes, or 3) blue eyes and pink skin at birth [6]. This was accomplished by viewing photo evidence of these traits or by personal inspection. Due to potential confusion between phenotypes of cream dilution and champagne dilution, all DNA samples from horses with the dilute phenotype were tested for the CR allele and data from those testing positive were not included in the population data.

DNA Extraction

DNA from blood samples was extracted using Puregene whole blood extraction kit (Gentra Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) according to its published protocol. Hair samples submitted by owners were processed using 5–7 hair bulbs according to the method described by Locke et al. (2002). The hair bulbs were placed in 100 µl lysis solution of 1× FastStart Taq Polymerase PCR buffer (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Roche), 0.5% Tween 20 (JT Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ) and 0.01 mg proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and incubated at 60°C for 45 minutes, followed by 95°C for 45 min to deactivate the proteinase K.

Microsatellite Genome Scan

The genome scan was done in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) multiplexes of 3 to 6 microsatellites per reaction. The 102 microsatellite markers used are listed in Table S3. Primers for these microsatellites were made available in connection with the USDA-NRSP8 project [20]. Two additional microsatellites were used; TKY329 [21] was selected based on its map location between two microsatellites used for genome scanning (UM010 and VHL209) and COOK007 was developed in connection with this study based on DNA sequence information from the horse genome sequence viewed in the UCSC genome browser [8] in order to investigate linkage within the identified interval. Primers for COOK007 were designed using Primer 3 software accessed online (Forward, 5′- 6FAM-CATTCCAAACACCAACAACC - 3′), (Reverse, 5′ – GGACATTCCAGCAATACAGAG – 3′) [22]. The initial scan was conducted on a subset of samples from Family 3; including sire 3, five non-champagne offspring and five champagne offspring. When the microsatellite allele contribution from the sire was not informative, (e.g. the sire and offspring had the same genotype), dams from family 3 were typed to determine the precise contribution from the sire. When the inheritance of microsatellite markers in family 3 appeared to be correlated with the inheritance of the CH allele, then the complete families A, B and C were typed and the data analyzed for linkage by LOD score analysis [23].

Amplification for fragment analysis was done in 10 µl PCR reactions using 1× PCR buffer with 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 µM of each dNTP, 1 µl genomic DNA from hair lysate, 0.1 U FastStart Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) and the individual required molarity of each primer from the fluorescently labeled microsatellite parentage panel primer stocks at the MH Gluck Equine Research Center. Samples were run on a PTC-200 thermocycler (MJ research, Inc., Boston, MA) at a previously determined optimum annealing temperature for each multiplex. Capillary electrophoresis of product was run on an ABI 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems Inc. ABI, Foster City, CA). Results were then analyzed using the current version of STRand microsatellite analysis software (http://www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/informatics/STRand/).

Sequencing

PCR template for sequencing was amplified in 20 µl PCR reactions using 1× PCR buffer with 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 µM of each dNTP, 1 µl genomic DNA from hair lysate, 0.2 U FastStart Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer) and 50 nM of each primer. Exon 2 of SLC36A1 was sequenced with the following primers: Forward (5′-CAG AGC CTA AGC CCA GTG TC-3′) and Reverse (5′-GGA GGA CTG TGT GGA AAT GG-3′) at an annealing temperature of 57°C. Primers used to sequence the other SLC36A1 exons and primers for sequencing genomic exons of SLC36A2 are provided in parts 1 and 2 respectively of Table S4. Template product was quantified on a 1% agarose gel, then amplified with BigDye Terminator v1.1 cycle sequencing kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems), cleaned using Centri-Sep columns (Princeton Separations Inc., Adelphia, NJ), and run on and ABI 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Six samples were initially sequenced: 2 suspected homozygous champagnes (based on production of all champagne dilution offspring when bred to at least 10 non-dilute dams), 2 heterozygotes, and 2 non-dilute horses. The results were analyzed and compared by alignment using ContigExpress from the Vector NTI Advance 10.3 software package (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, California).

Reverse Transcription (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR was performed in 25 µl reactions a Titan One Tube RT-PCR Kit (Roche) according to enclosed protocol with the primers listed in part 3 of Table S4. RNA from different tissues of non-dilute horses was used to acquire partial cDNAs containing the first two exons for SLC36A1, first three exons SLC36A2 and first 4 exons of SLC36A3. The cDNA acquired was sequenced and the resulting sequences were verified for their respective genes with a BLAT search using the equine assembly v2 in ENSEMBL (http://www.ensembl.org/Equus_caballus/index.html) genome browser. RT-PCR was also performed utilizing RNA extracted from skin, kidney and testes of non-dilute animals currently in lab stocks. SLC36A1 cDNA was produced from the skin and blood using 50 ng RNA per reaction. SLC36A2 cDNA was produced from testes using 1 mRNA per RT-PCR reaction then following up with a nested PCR for shorter product. SLC36A2 cDNA was produced from skin using 50 ng mRNA per RT-PCR reaction. Nested PCR was not necessary. SLC36A3 cDNA was produced from testes using 1 ug mRNA per reaction. 9 µl of initial reaction was visualized on a 2% agarose gel to check for visible bands of product. When product was not initially detected an additional 20 µl PCR was performed in reactions as outlined above using 5 µl of RT product in the place of hair lysate per reaction. Detected product was then sequenced with the protocol listed above. Sequences were then used in a BLAST search using equine genome assembly 2 on ENSEMBL genome browser to verify the correct cDNA was amplified.

Custom TaqMan Probe Assay

A Custom TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems) was designed for c.188C/G SNP in filebuilder 3.1 software (Applied Biosystems) to test the population distribution of the SLC36A1 alleles. A similar assay was also designed to test for the cream SNP. These assays were run on a 7500HT Fast Real Time-PCR System (Applied Biosystems). All dilute horses tested for SLC36A1 variants were concurrently tested for SLC45A variants. Horses testing positive for CR alleles were not used in the dataset to avoid any confusion over the origin of their dilution phenotype.

Supporting Information

Pedigrees of Three Sire Families used in Genome Scan.

(0.55 MB TIF)

Haplotype Data for Three Sire Families.

(0.25 MB DOC)

Sequence Variants Detected in SPARC, SLC36A1, and SLC36A2.

(0.14 MB DOC)

Microsatellite Markers used For Genome Scan.

(0.20 MB DOC)

Sequencing and RT-PCR Primers.

(0.07 MB DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Katie Mroz-Barrett for work on the project, Bea Kinkade, Val Kleinhetz, Pam Capurso, Carolyn Sheperd and all the other horse owners who submitted samples from horses with different hair color phenotypes and to Dr. Teri Lear for critically reading the manuscript. The microsatellites used for genome scanning were provided through the auspices of the USDA-NRSP8 program and the Dorothy Russell Havemeyer Foundation. This work was conducted in connection with a project of the Morris Animal Foundation and the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of Kentucky and is published as paper number 08-14-019.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work was funded by Morris Animal Foundation.

References

- 1.Mariat D, Taourit S, Guerin G. A Mutation in the MATP gene causes the cream coat colour in the horse. Genet Sel Evol. 2002;35(1):119–133. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-35-1-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunberg E, Andersson S, Cothran G, Sandberg K, Mikko S, et al. A missense mutation in PMEL17 is associated with the Silver coat color in the horse. BMC Genet. 2006 doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-7-46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locke M, Ruth LS, Millon LV, Penedo MCT, Murray JD, et al. The cream dilution gene, responsible for the palomino and buckskin coat colours, maps to horse chromosome 21. Anim Genet. 2001;32:340–343. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2001.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adalsteinsson S. Inheritance of the palomino color in Icelandic horses. J Hered. 1974;65:15–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a108448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowling A. Genetics of Color variation. In: Bowling AT, Ruvinsky A, editors. New York: CABI Publishing; 2000. p. 62. In the Genetics of the Horse Edited by: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sponenberg D. Equine Color Genetics. 2nd Edition. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 2003. pp. 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheridan CM, Magee RM, Hiscott PS, Hagan S, Wong DH, McGalliard JN, Grierson The role of matricellular proteins thrombospondin-1 and osteonectin during RPE cell migration in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2002;25(5):279–85. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.25.5.279.13492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bermingham J, Pennington J. Organization and expression of the SLC36 cluster of amino acid transporter genes. Mamm Genome. 2004 doi: 10.1007/s00335-003-2319-3. DOI:10.1007/s00335-003-2319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boll M, Foltz M, Rubio-Aliaga I, Daniel H. A cluster of proton/amino acid transporter genes in the human and mouse genomes. Genomics. 2003;82:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penedo MCT, Millon LV, Bernoco D, Bailey E, Binns M, et al. International Equine Gene Mapping Workshop Report: A comprehensive linkage map constructed with data from new markers and by merging four mapping resources. Cytogenet and Genome Res. 2005;111:5–15. doi: 10.1159/000085664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, et al. The Human Genome Browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graf J, Hodgson R, van Daal A. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the MATP gene are associated with normal human pigmentation variation. Hum Mutat. 2005;25(3):278–84. doi: 10.1002/humu.20143. 2005 Mar; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamason RL, Mohideen MA, Mest JR, Wong AC, Norton HL, et al. SLC24A5, a putative cation exchanger, affects pigmentation in zebrafish and humans. Science. 2005;310:1782–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1116238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoekstra HE. Genetice, development and evolution of adaptive pigmentation in vertebrates. Heredity. 2006;97:222–234. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, Fei YJ, Anderson CM, Wake KA, Miyauchi S, et al. Structure, function and immunolocalization of a proton-coupled amino acid transporter (hPAT1) in the human intestinal cell line Caco-2. J Physiol. 2003;15;546(Pt 2):349–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wreden CC, Johnson J, Tran C, Seal RP, Copenhagen DR, et al. The H+-coupled electrogenic lysosomal amino acid transporter LYAAT1 localizes to the axon and plasma membrane of hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;15;23(4):1265–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01265.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kushimoto T, Basrur V, Valencia J, Matsunaga J, Vieira W, et al. A model for melanosome biogenesis based on the purification and analysis of early melanosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;Vol. 98 no. 19:10698–10703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191184798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watabe H, Valencia JC, Yasumoto K, Kushimoto T, Ando H, et al. Regulation of Tyrosinase Processing and Trafficking by Organellar pH and by Proteasome Activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;279:7971–7981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watabe H, Valencia JC, LePape E, Yamaguchi Y, Nakamura M, et al. Involvement of Dynein and Spectrin with Early Melanosome Transport and Melanosomal Protein Trafficking. J Invest Dermatol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701019. DOI: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guérin G, Bailey E, Bernoco D, Anderson I, Antczak DF, et al. Report of the international equine gene mapping workshop: male linkage map. Anim Genet. 1999;30:341–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.1999.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tozaki T, Mashima S, Hirota K, Miura N, Choi-Miura NH, Tomita M. Characterization of equine microsatellites and microsatellite-linked repetitive elements (eMLREs) by efficient cloning and genotyping methods. DNA Res. 2001;8(1):33–45. doi: 10.1093/dnares/8.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rozen S, Skaletsky HJ. Primer3. 1998. Code available at http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/genome_software/other/primer3.html. Accessed at: http://biotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Morton NE. Sequential tests for the detection of linkage. Amer. J. Hum. Genet. 1956;7:277–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Pedigrees of Three Sire Families used in Genome Scan.

(0.55 MB TIF)

Haplotype Data for Three Sire Families.

(0.25 MB DOC)

Sequence Variants Detected in SPARC, SLC36A1, and SLC36A2.

(0.14 MB DOC)

Microsatellite Markers used For Genome Scan.

(0.20 MB DOC)

Sequencing and RT-PCR Primers.

(0.07 MB DOC)