Abstract

Two new neoclerodane diterpenes, salvinicins A (4) and B (5), were isolated from the dried leaves of Salvia divinorum. The structures of these compounds were elucidated by spectroscopic techniques, including 1H and 13C NMR, NOESY, HMQC, and HMBC. The absolute stereochemistry of these compounds was assigned on the basis of single crystal X-ray crystallographic analysis of salvinicin A (4) and a 3,4-dichlorobenzoate derivative of salvinorin B.

The genus Salvia is one of the most widespread members of the Lamiaceae (formerly Labiatae) family and is featured prominently in the pharmacopeias of many countries throughout the world.1 Among these is Salvia divinorum Epling & Játiva, a sage native to Oaxaca, Mexico. An infusion prepared from four or five pairs of fresh or dried leaves is used by the Mazatec Indians to stop diarrhea, relieve headache and rheumatism, and to treat a ‘semi-magical’ disease known as panzón de barrego or swollen belly.2 S. divinorum is also used in traditional spiritual practices of the Mazatecs to produce “mystical” or hallucinogenic experiences.2

The active ingredient in S. divinorum is salvinorin A (1a) (Figure 1).3,4 Salvinorin A as well as salvinorin B (1b), were identified nearly simultaneously by Ortega and Valdés III, et al.5,6 A dose of 200 to 500 μg, when smoked, produces profound hallucinations lasting up to one hour.7,8 Interestingly, 1a does not act at the presumed molecular target responsible for the actions of classical hallucinogens, the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.9–11 Rather, 1a is a potent and selective κ opioid receptor agonist in vitro and in vivo.12,13

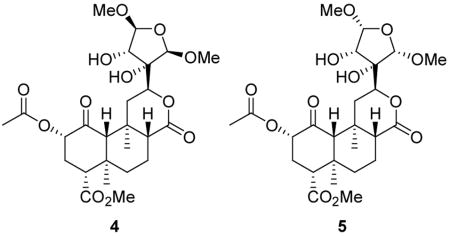

Figure 1.

Structures of salvinorin A (1a), B (1b), LSD (2), morphine (3), salvinicin A (4), salvinicin B (5), and dichlorobenzoyl derivative 6.

Presently, 1a and S. divinorum are gaining popularity as recreational drugs.14,15 Advertisements for dried S. divinorum leaves, as well as recipes for leaf extracts, elixirs and tinctures may be found posted on the internet.16 Young adults and adolescents have begun to smoke the leaves and leaf extracts of the plants to induce powerful hallucinations.17

Currently, S. divinorum is unregulated in most countries and available throughout the world for purchase over the internet. However, it is listed as a controlled substance in Denmark, Australia, and Italy. Obtaining S. divinorum is easy in countries where it is unregulated, and it represents a cheap, easy solution for those who wish to experiment with drugs and perception altering substances. To date, U.S. laws for controlled substances do not ban the sale of S. divinorum or its active components. This has resulted in various on-line botanical companies advertising and selling S. divinorum as a legal alternative to other regulated plant hallucinogens. Therefore, it is predictable that its misuse will increase.

As a hallucinogen, 1a is structurally unique. It bears no similarity to classical hallucinogens, such as LSD (2). Furthermore, it has no similarity to other opioid ligands, such as morphine (3). Given its potential for abuse, as well as, its unique pharmacological properties, we18–20 and others21–23 have begun to study the chemistry and pharmacology associated with constituents from S. divinorum.

Previous phytochemical investigation of S. divinorum resulted in the identification of several neoclerodane diterpenes present in the leaves, salvinorins A – F and divinatorins A – C.5,6,8,24,25 Here, we report the identification of two new neoclerodane diterpenes present in commercially available S. divinorum leaves.

Commercially available dried leaves of S. divinorum were extracted with acetone, and the acetone extract was subjected to repeated flash column chromatographies using a variety of solvent mixtures to afford salvinicins A (4) (65 mg) and B (5) (14 mg). Compound 4 gave a pseudomolecular ion peak at m/z 551.2080 ([M+Na]+) in the HRESIMS suggesting a molecular formula of C25H36O12 and an index of unsaturation of 8. Its IR spectrum showed absorption bands for hydroxyl (3426 cm−1, broad), carbonyl (1718 cm−1), and alkene (1646 cm−1) functionalities.

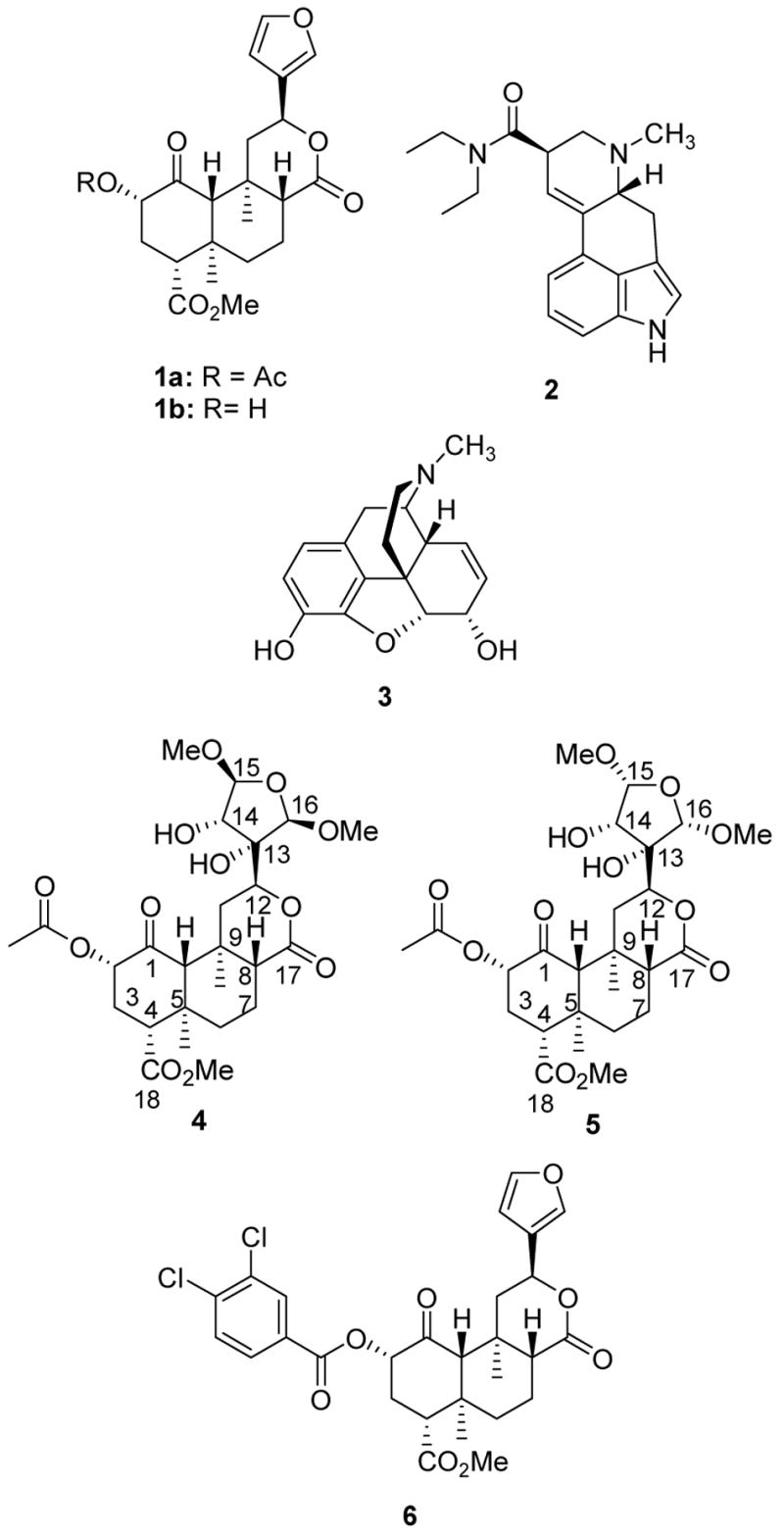

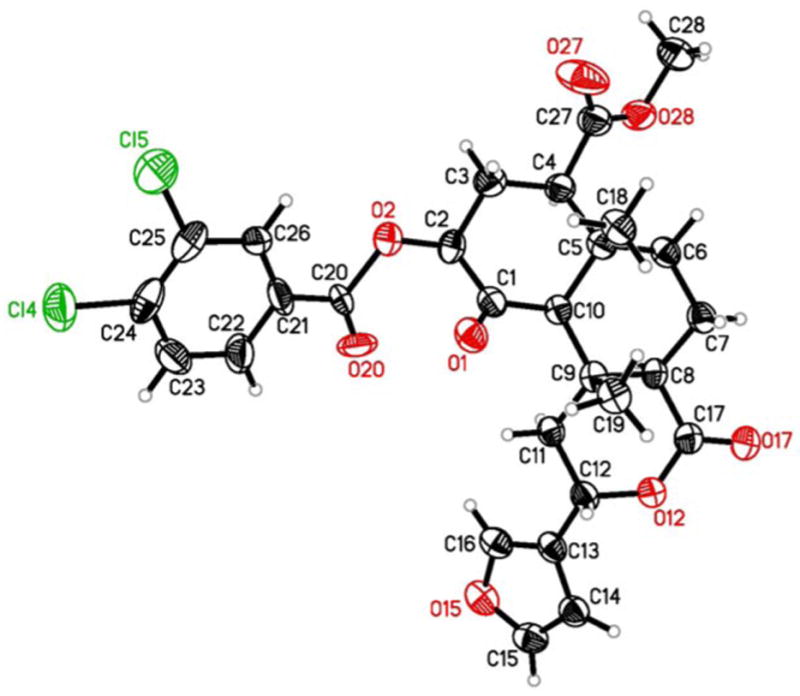

Comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 4 with those of 1a5,6 suggested that these compounds were structurally similar. Thus, most chemical shift assignments for the trans-decalin portion and ring A substituents of 4 could be determined readily by comparison with 1a. The most striking features of the 1H NMR spectrum of 4 were the absence of furanoid protons and the presence of two additional methoxyl signals (δ 3.47 and 3.36) and three additional oxymethine protons (δ 4.93, 4.70, and 4.43) as compared to 1a.5,6 The 13C NMR spectrum showed resonances typical of dioxygenated carbons at δ 110.6 and 107.9. Two oxygen-linked carbons were observed at δ 80.4, of which one was quaternary and one was tertiary, as deduced from the DEPT-135 spectrum. HMQC analysis indicated that carbons at δ 110.6 and 107.9 were attached directly to protons at δ 4.93 and 4.70, respectively. Signals at δ 3.68 and 3.40 disappeared on addition of D2O, suggesting the presence of two hydroxyl groups. The aforementioned spectral data suggested that 4 had lost the furan ring present in 1a due to oxygenation. Presence of HMBC crosspeaks between the methoxyl signals at δH 3.47 and 3.36 and carbons at δC 110.6 and 107.9, respectively, allowed for placement of these groups at the α positions of the reduced furan ring. Further HMBC, HMQC, and COSY analysis enabled gross structural assignment of 4 deducing the structure shown. Assignment of relative stereochemistry of C-14 to C-16 was achieved with the aid of NOESY data. In the NOESY experiment, crosspeaks were observed between the α-tetrahydrofuran (THF) protons. A NOESY correlation was also observed between H-12 and H-14. No NOESY crosspeaks were seen between either of the α-THF protons and H-14, suggesting that the α-THF protons and H-14 were on opposite sides of the ring. Although such negative data are not conclusive, this assignment was confirmed by single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of 4 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results from the X-ray analysis on 4 drawn from the experimentally determined coordinates with the thermal parameters at the 20% probability. There was some disorder in the crystal structure that was successfully modeled. This figure represents the major component of that disorder.

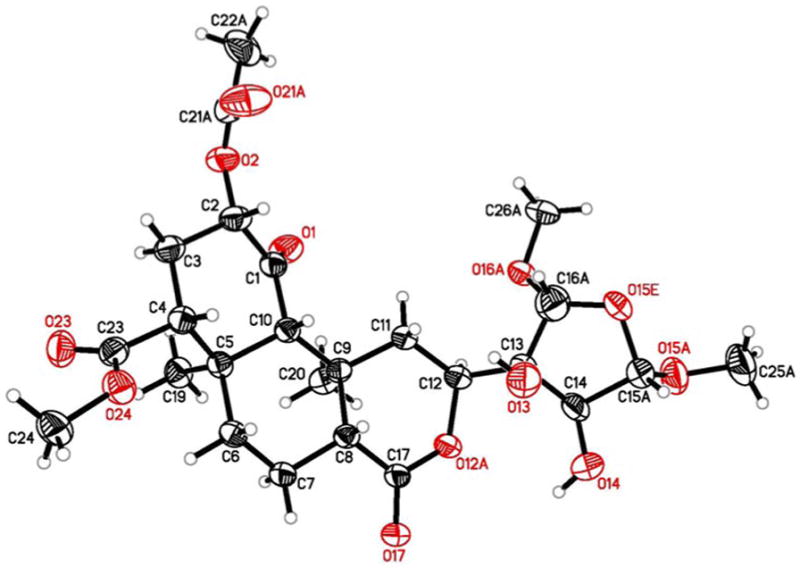

A molecular formula of C25H36O12 was determined by HRESIMS (m/z 551.2089 [M+Na]+) for compound 5 indicating an index of unsaturation of 8. Gross comparison of the NMR spectra of 4 and 5 suggested that they were structurally similar. Like compound 4, the 1H NMR spectrum of 5 was devoid of aromatic signals and showed oxymethines (δ 4.94 and 4.92), which could be assigned to the α positions of the reduced furan ring. A D2O exchange experiment indicated that 5 also possessed two hydroxyl groups; signals at δ 4.15 and 2.37 disappeared on addition of D2O, and this was accompanied by resolution of the broad signal at δ 4.02 to a clean doublet. In an HMBC experiment, methoxyl protons at δH 3.47 and 3.42 correlated to dioxygenated carbons at δC 111.3 and 108.4, respectively, indicating a similar substitution pattern to that seen in 4. Further HMBC analysis enabled elucidation of the structural connectivity of 5. As in the NOESY spectrum of 4, the NOESY spectrum of 5 showed crosspeaks between H-12 and H-14 (Figure 3). In addition, H-14 showed crosspeaks to H-15 and H-16 suggesting that H-14, H-15, and H-16 are on the same face of the tetrahydrofuran ring. Thus, the structure of 5 is proposed for salvinicin B.

Figure 3.

NOESY correlations in salvinicin B (5).

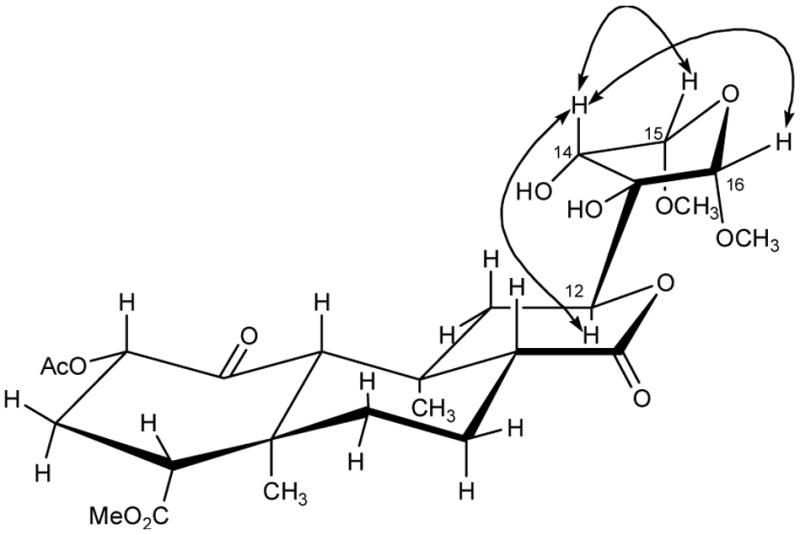

The absolute stereochemistry of 1a and 1b were determined previously through use of a non-empirical exciton chirality circular dichroism (CD) method.26 However, the absolute sterochemistry has not been confirmed unambiguously by X-ray crystallographic analysis. In an effort to confirm the stereochemistry of 1a and 1b unequivocally, as well as that of salvinicins A and B, a 3,4-dichlorobenzoyl derivative (6) was prepared. This compound was obtained in 70% yield by reacting 1b with 3,4-dichlorobenzoyl chloride under conditions described previously.18 A single crystal X-ray diffraction study of 6 was carried out, from which its absolute stereochemistry was determined (Flack parameter27 = 0.00(3)) and is as shown (Figure 4). Thus, the absolute stereochemistry of 1a and 1b was determined unambiguously and by extension, the absolute stereostructure of 4 is proposed as depicted.

Figure 4.

Results from the X-ray analysis on 6 drawn from the experimentally determined coordinates with the thermal parameters at the 20% probability. There was some disorder in the crystal structure that was successfully modeled. This figure represents the major component of that disorder.

The 3,4-dihydroxy-2,5-dimethoxytetrahydro-3-furyl moiety seen in 4 and 5 is rare. This moiety has been reported previously in diterpenes of the clerodane and labdane classes, as well as in other classes of natural products.28–33 However, this is the first report of this highly oxygenated tetrahydrofuran ring system in compounds isolated from the Salvia genus. In addition, this description is the first report of an X-ray crystallographic structure of this type of reduced furan ring system.

Pharmacologic evaluation of these compounds at μ, κ, and δ opioid receptors was then conducted using a [35S]GTPγS assay.34 Initial screening at 10 μM indicated that 4 and 5 showed activity at κ and μ receptors, respectively. Further work indicated that salvinicin A (4) exhibited partial κ agonist activity with an EC50 value of 4.1 ± 0.6 μM (Emax = 80% relative to (−)-U50,488H). Interestingly, salvinicin B (5) exhibited antagonist activity at μ receptors with a Ki of > 1.9 μM. This is the first report of a neoclerodane diterpene with opioid antagonist activity and represents a new lead in the development of opioid receptor antagonists.

At present, there are few methods for the synthesis of neoclerodane diterpenes, including 1a. Recently, the first total synthesis of the neoclerodane (−)-methyl barbascoate from an (R)-(−)-Weiland-Meischer ketone analogue was reported.35 This unique architecture, and the potential biological activity of these compounds, make them attractive targets for the synthetic chemist.

In conclusion, two novel neoclerodane diterpenes with opioid receptor activity have been isolated from commercially available S. divinorum leaves. Salvinicins A (4) and B (5) are unique neoclerodanes which possess a 3,4-dihydroxy-2,5-dimethoxytetrahydrofuran ring. The absolute stereochemistry of these molecules has been assigned through X-ray crystallographic analysis of 6.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details on the isolation of 4 and 5; physical and spectral data of 4, 5, and 6; and X-ray data of 4 and 6. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Table 1.

NMR Data for compounds 4 and 5 in CDCl3

| entry | 4δC | 4 δH (J in Hz) | HMBCa | 5 δC | 5 δH (J in Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 201.9 | 2, 3, 10 | 201.9 | ||

| 2 | 74.9 | 5.17 dd (7.9, 12.3) | 3, 4, 10 | 74.9 | 5.12 dd (8.1, 12.1) |

| 3 | 30.9 | 2.27 m; 2.32 m | 2 | 30.9 | 2.28 m; 2.31 m |

| 4 | 53.4 | 2.74 dd (4.0, 12.8) | 3, 10, 19 | 53.4 | 2.76 dd (4.3, 12.5) |

| 5 | 42.0 | 3, 4, 6, 10, 19 | 42.1 | ||

| 6 | 38.0 | 1.55 m; 1.77 ddd (2.9, 2.9, 10.1) | 4, 8, 10, 19 | 38.1 | 1.57 m; 1.75 m |

| 7 | 18.1 | 1.57 m; 2.08 m | 8 | 18.2 | 1.57 m; 2.09 m |

| 8 | 50.2 | 2.08 m | 7, 11, 20 | 50.4 | 2.04 dd (2.9, 11.7) |

| 9 | 34.6 | 7, 10, 11, 20 | 34.7 | ||

| 10 | 64.1 | 2.18 s | 4, 6, 11, 19, 20 | 64.0 | 2.22 s |

| 11 | 35.2 | 1.67 dd (10.7, 12.8); 2.20 dd (6.2, 12.8) | 12 | 35.6 | 1.57 m; 2.13 dd (6.1, 11.6) |

| 12 | 80.4 | 4.82 dd (6.2, 10.7) | 11, 14 | 77.2 | 4.90 dd (6.1, 11.6) |

| 13 | 80.4 | 80.7 | |||

| 14 | 80.0 | 4.43 dd (3.5, 4.5) | 12, 15, 16 | 76.2 | 4.02 br s |

| 15 | 110.6 | 4.93 d (3.5) | 14, 16, 15-OCH3 | 111.3 | 4.92 d (3.4) |

| 16 | 107.9 | 4.70 s | 12, 15, 16-OCH3 | 108.4 | 4.94 s |

| 17 | 172.2 | 7, 8 | 171.6 | ||

| 18 | 171.6 | 3, 4 | 171.7 | ||

| 19 | 16.1 | 1.08 s | 4 | 16.2 | 1.07 s |

| 20 | 15.3 | 1.33 s | 8 | 15.1 | 1.35 s |

| 2-OCOCH3 | 169.8 | 2 | 170.7 | ||

| 2-OCOCH3 | 20.6 | 2.17 s | 20.6 | 2.18 s | |

| 15-OCH3 | 56.5 | 3.47 s | 15 | 56.3 | 3.47 s |

| 16-OCH3 | 55.2 | 3.36 s | 16 | 55.2 | 3.42 s |

| 18-OCH3 | 51.9 | 3.72 s | 51.9 | 3.72 s | |

| 13-OH | 3.68 s | 16 | 4.15 br s | ||

| 14-OH | 3.40 d (4.5) | 2.37 br s |

Protons correlating with carbon shift. These correlations were observed for both molecules.

Acknowledgments

The authors (WWH, KT, TEP) thank the Biological Sciences Funding Program of the University of Iowa for financial support. The X-ray crystallographic work was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH, DHHS, and the Office of Naval Research.

References

- 1.Kintzios SE. Sage: The Genus Salvia. Harwood Academic Publishers; Amsterdam: 2000. pp. 1–296. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valdes LJ, III, Diaz JL, Paul AG. J Ethnopharmacol. 1983;7:287–312. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(83)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siebert DJ. J Ethnopharmacol. 1994;43:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valdes LJ., III J Psychoact Drugs. 1994;26:277–283. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1994.10472441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortega A, Blount JF, Manchand PS. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1982:2505–2508. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valdes LJ, III, Butler WM, Hatfield GM, Paul AG, Koreeda M. J Org Chem. 1984;49:4716–4720. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siebert DJ. J Ethnopharmacol. 1994;43:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valdes LJ, III, Chang HM, Visger DC, Koreeda M. Org Lett. 2001;3:3935–3937. doi: 10.1021/ol016820d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glennon RA, Titeler M, McKenney JD. Life Sci. 1984;35:2505–2511. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Titeler M, Lyon RA, Glennon RA. Psychopharmacology. 1988;94:213–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00176847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egan CT, Herrick-Davis K, Miller K, Glennon RA, Teitler M. Psychopharmacology. 1998;136:409–414. doi: 10.1007/s002130050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth BL, Baner K, Westkaemper R, Siebert D, Rice KC, Steinberg S, Ernsberger P, Rothman RB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11934–11939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182234399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butelman ER, Harris TJ, Kreek MJ. Psychopharmacology. 2004;172:220–224. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Drug Intelligence Center. Information Bulletin: Salvia divinorum; 2003-L0424-003. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giroud C, Felber F, Augsburger M, Horisberger B, Rivier L, Mangin P. Forensic Sci Int. 2000;112:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valdes III, L. J., personal communication. In 2003.

- 17.Hazelden Foundation. www.research.hazelden.org 2004.

- 18.Tidgewell K, Harding WW, Schmidt M, Holden KG, Murry DJ, Prisinzano TE. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:5099–5102. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt MS, Prisinzano TE, Tidgewell K, Harding WW, Butelman ER, Kreek MJ, Murry DJ. J Chromatogr B. 2005;818:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harding WW, Tidgewell K, Byrd N, Cobb H, Dersch CM, Butelman ER, Rothman RB, Prisinzano TE. J Med Chem. 2005;48 doi: 10.1021/jm048963m. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chavkin C, Sud S, Jin W, Stewart J, Zjawiony JK, Siebert DJ, Toth BA, Hufeisen SJ, Roth BL. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:1197–1203. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munro TA, Rizzacasa MA, Roth BL, Toth BA, Yan F. J Med Chem. 2005;48:345–348. doi: 10.1021/jm049438q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Tang K, Inan S, Siebert D, Holzgrabe U, Lee DY, Huang P, Li JG, Cowan A, Liu-Chen LY. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:220–230. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munro TA, Rizzacasa MA. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:703–705. doi: 10.1021/np0205699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bigham AK, Munro TA, Rizzacasa MA, Robins-Browne RM. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:1242–1244. doi: 10.1021/np030313i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koreeda M, Brown L, Valdes LJ. Chem Lett. 1990:2015–2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flack HD. Acta Cryst. 1983;A39:876–881. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin TS, Ohtani K, Kasai R, Yamasaki K. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:1729–1736. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed M, Ahmed AA. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:2715–2716. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hungerford NL, Sands DPA, Kitching W. Aus J Chem. 1998;51:1103–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrow CJ, Blunt JW, Munro MHG. J Nat Prod. 1989;52:346–359. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Q, Hao X, Chen Y, Zou C. Chinese Chem Lett. 1996;7:25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ono M, Yanaka T, Yamamoto M, Ito Y, Nohara T. Tennen Yuki Kagobutsu Toronkai Koen Yoshishu. 42. 2000. pp. 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu H, Hashimoto A, Rice KC, Jacobson AE, Thomas JB, Carroll FI, Lai J, Rothman RB. Synapse. 2001;39:64–69. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<64::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagiwara H, Hamano K, Nozawa M, Hoshi T, Suzuki T, Kido F. J Org Chem. 2005;70:2250–2255. doi: 10.1021/jo0478499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crystallographic data for salvinicin A (4) (deposition no. CDCC 265522) and the 3,4-dichlorobenzoyl derivative of salvinorin B (6) (deposition no. CDCC 265523) have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge, on application to the Director, CDCC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK [Fax: 44-(0)1223-306033 or email: deposit@cdcc.cam.ac.uk].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details on the isolation of 4 and 5; physical and spectral data of 4, 5, and 6; and X-ray data of 4 and 6. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.