Abstract

Broken symmetry density functional theory (BS-DFT) has been used to address the hyperfine parameters of the single atom ligand X, proposed to be coordinated by six iron ions in the center of the paramagnetic FeMo-cofactor (FeMoco) of nitrogenase. Using the X = N alternative, we recently found that the any hyperfine signal from X would be small (calculated Aiso(X=14N) = 0.3 MHz), due to both structural and electronic symmetry properties of the [Mo-7Fe-9S-X] FeMoco core in its resting S = 3/2 state. Here we extend our BS-DFT approach to the 2e− reduced S = 1/2 FeMoco state. Alternative substrates coordinated to this FeMoco state effectively perturb the electronic and/or structural symmetry properties of the cofactor. Using an example of an allyl alcohol (H2C=CH-CH2-OH) product ligand, we consider three different binding modes at single Fe site and three different BS-DFT spin state structures, and show that this binding would enhance the key hyperfine signal Aiso(X) by at least one order of magnitude (3.8 ≤ Aiso(X=14N) ≤ 14.7 MHz) and this result should not depend strongly on the exact identity of X (N, C, or O). The interstitial atom, when nucleus has a nonzero magnetic moment, should therefore be observable by ESR methods for some ligand-bound FeMoco states. In addition, our results illustrate structural details and likely spin-coupling patterns for models for early intermediates in the catalytic cycle.

1. INTRODUCTION

To benefit from the ∼78% abundance of molecular nitrogen in the atmosphere, nature has developed a class of prokaryotes called diazotrophs. Hosted in vivo solely by diazotrophs, the nitrogenase metalloenzyme performs a multielectron/multiproton reduction of relatively inert dinitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3). An iron-molybdenum cofactor1 FeMoco which is unique to nitrogenases, see Figure 1, is the site for reduction of N2 and a variety of nonphysiological substrates.

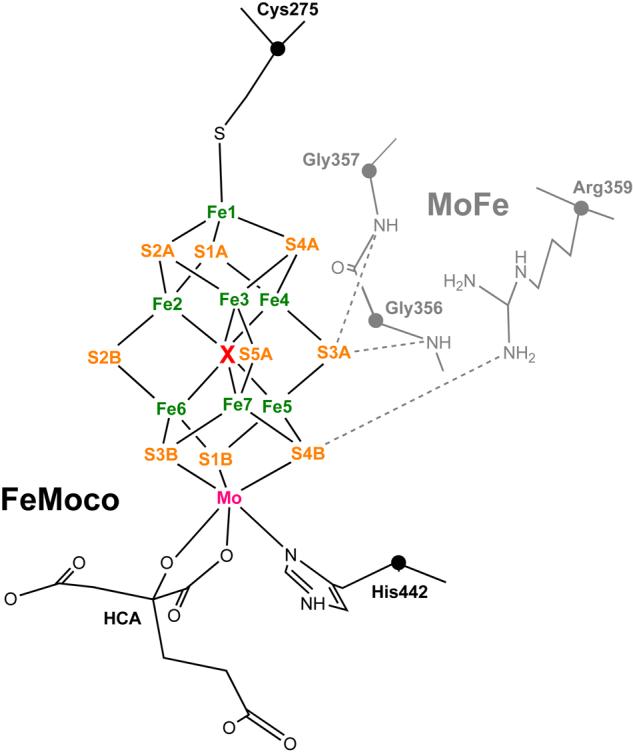

FIGURE 1.

FeMoco of nitrogenase with its interstitial ligand X coordinated by the six iron atoms Fe2-7. The covalent ligands (in black) to the cofactor [Mo-7Fe-9S-X] core are Cys275, His442 and homocitrate (HCA). First shell MoFe protein ligands (in gray) Arg359 and Gly356/357 are tentative origins of N1 and N2 nitrogen hyperfine signals, respectively (see Section 1 of the text). FeMoco atom namings follow their crystallographic notation.2 Cα carbons are given as spheres.

In 2002, electron density was resolved inside the FeMoco iron trigonal prismane ([6Fe]) which can be ambiguously associated with a single N, C, or O atom2. Despite intensive efforts from both the experimental and theoretical sides, the identity of this interstitial atom (denoted X) is still open to debate3. X = N has been supported by most theoretical studies,4,5 but experiments using electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) or electron spin-echo envelope modulation (ESEEM) have not detected any observable signals from 14,15N in the resting S = 3/2 state of FeMoco (called MN or E0, proposed [Mo4+4Fe2+3Fe3+] oxidation state for the metals).6-8 Isotropic hyperfine signals of Aiso(14N) = 1.05 MHz and Aiso(14N) = 0.5 MHz were reported for the MoFe protein containing FeMoco bound, but these signals were not seen for the cofactor extracted into N-methyl formamide (NMF) solvent.6,7,9 Called N1 and N2, the two above modulations were assigned to nitrogens of the polypeptide, tentatively side chain nitrogen of Arg359 and backbone nitrogen of Gly356/357, see Figure 1. No strong natural abundance 13C signals have been detected either,6 precluding X = C identification. Recent ENDOR/ESEEM measurements put upper bounds on the interstitial atom hyperfine signal, if present: for X = N, Aiso(X=14N) ≤ 0.05 MHz, and for X = C, Aiso(X=13C) ≤ 0.1 MHz.8 These upper bounds essentially reflect state of the art sensitivity of the most recent experiments. No 17O ENDOR/ESEEM assessment for X = O candidate has yet been reported; 17O experimental setup would be prohibitively expensive.

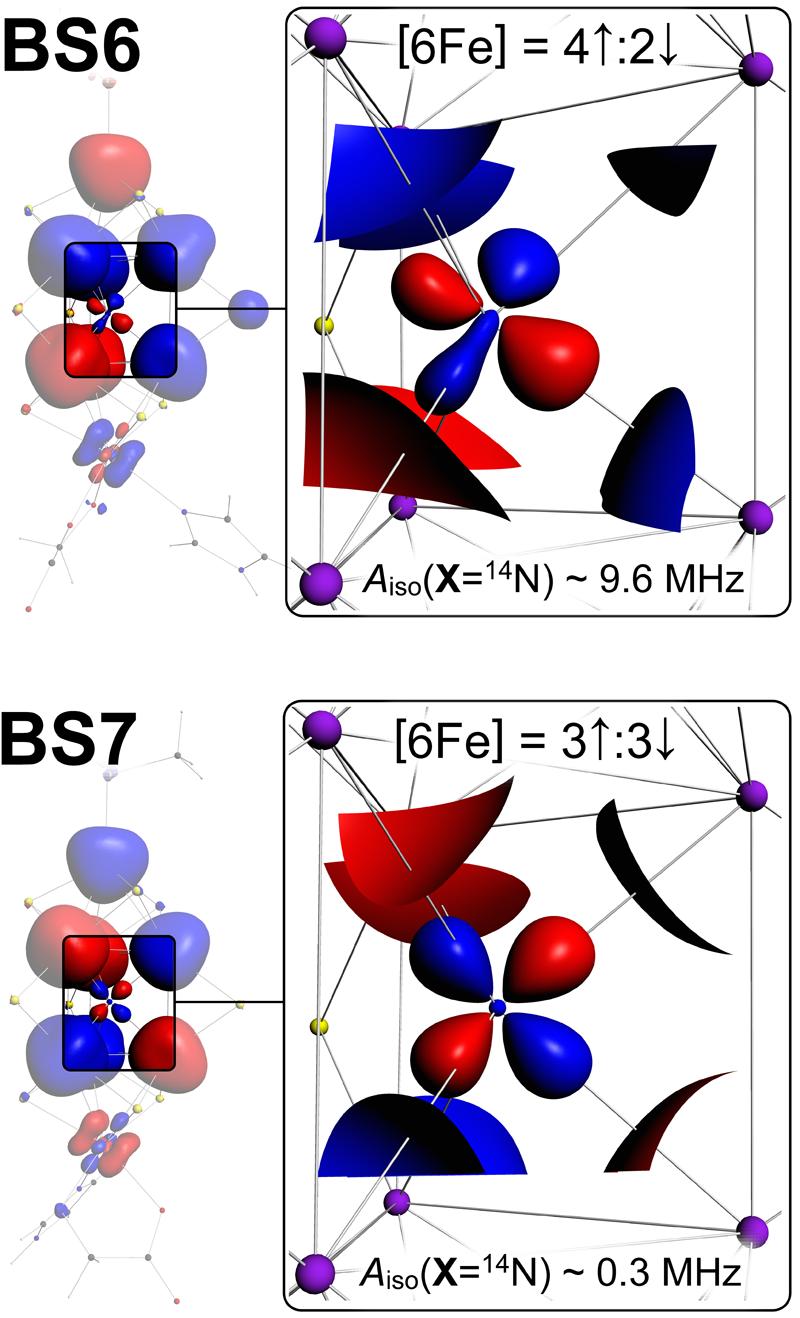

Using density functional theory (DFT) calculations in combination with the broken symmetry (BS) approach for spin coupling, small Aiso(X=14N/13C/17O) = 0.3/1.0/0.1 MHz were obtained recently for X candidates N, C, and O in the resting FeMoco oxidation state.8 The absence of a strong X hyperfine signal was rationalized as an outcome of the electronic and structural symmetry properties of the [6Fe] prismane, formed by the six irons adjacent to X: a cancellation of [6Fe] irons electron spin densities in a 3↑:3↓ (3 − 3 = 0) spin coupling, in concert with the symmetry of the prismane structure, results in a very small point spin density ρ = 0.4·10−2 a.u. (atomic units, or electrons per cubic bohr) at the X nucleus location. In contrast, 4↑:2↓ (4 − 2 = 2) spin coupling of the six prismane irons yields significantly larger ρ = −2.5·10−2 a.u. Notably, all the ten ‘simple’ (parallel or antiparallel) spin alignments (called broken symmetry (BS) states, see Section 2.3) available for the resting state FeMoco possess either 3↑:3↓ or 4↑:2↓ pattern within [6Fe]10 (see Chart 2, the first BSx column). For the two lowest energy BS states, BS7 (≡0.0 kcal/mol, 3↑:3↓) and BS6 (+6.6 kcal/mol, 4↑:2↓), our calculated Aiso(X=14N) values are 0.3 and 9.6 MHz respectively, 8 see Figure 2. For the resting state FeMoco, BS7 spin coupling is therefore now favored because it (i) gives the lowest energy among the BS states and (ii) conforms to the lack of an observed X hyperfine signal. While our Aiso(X=14N) = 0.3 MHz for BS7 is several times larger than the experimental Aiso(X=14N) = 0.05 MHz upper bound,8 combined uncertainties in the BS-DFT approach may easily result in ∼0.3 MHz absolute error in the computed X isotropic hyperfine constant.

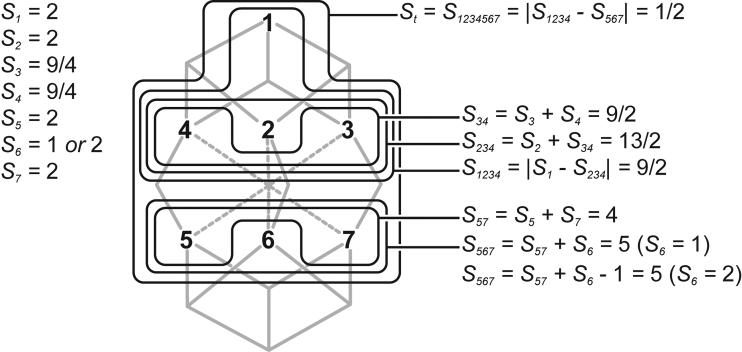

CHART 2.

Spin coupling alignments (BS states) available for the seven Fe sites of FeMoco in the resting state (BSx, x = 1-10), and 2e− reduced state (BSx, x = 1-10; BSx-, x = 1-10; BSNx, x = 1-6). The energies (kcal/mol), when available, are given for the 2e− reduced state relatively to the most stable spin coupling, BS2.

FIGURE 2.

3D spin density maps for the resting state FeMoco BS6 and BS7 spin couplings. Point spin density ρ = ±0.01 a.u. (atomic units, or electron per cubic bohr) isosurfaces correspond to the hyperfine coupling |Aiso(X=14N)| ∼ 5 MHz. Blue/red surfaces are for the positive/negative ρ contour values, correspondingly. For BS7, the node (|ρ| < 0.01 a.u.) of the spin density at the X position is manifested in small Aiso(X=14N) ∼ 0.3 MHz. Contrary to BS7, |ρ| > 0.01 a.u. at the X position for BS6, manifested in Aiso(X=14N) ∼ 9.6 MHz. 3D isosurfaces were generated using ADF View, based on our recent DFT calculations.8

We thus expect that the hyperfine coupling of X to the FeMoco spin can be significantly enhanced by either electronic or structural symmetry perturbations of the [6Fe] prismane. A ligand binding at one of the [6Fe] irons would potentially lead to such perturbations. However, no species are known to coordinate at the iron prismane of the cofactor in its resting state. Some substrates can be trapped in a paramagnetic S = 1/2 state, generated via 2e− reduction and, presumably, 2H+ protonation of the cofactor.11,12 Notably, the 2e− reduced FeMoco itself has been characterized as S = 1/2 state12 in the absence of any extra substrate. Also, 57Fe ENDOR hyperfine data for S = 1/2 states named “SEPR1” and “lo-CO” which trap different ligands C2H4 (resulting from reductive binding of C2H2) and CO, correspondingly, indicate that the electronic properties, including magnetic coupling on 57Fe, of these two intermediates are similar.6 Based on the above considerations, we will first assume that the electronic structure of the [Mo-7Fe-9S-X] core is generally similar for all relevant S = 1/2 2e− reduced FeMoco core species, regardless of ligand binding. We will provide our further support for this assumption below.

Elucidating ligand binding modes at FeMoco is anticipated to shed light onto the nitrogenase reaction mechanism. Despite intensive research in this area, there is limited information at the molecular level about precise geometry of species when bound to FeMoco. Substrates featuring unsaturated C=C/C≡C bonds are thought to coordinate at the [6Fe] prismane face, formed by Fe numbers 2, 3, 6, and 7 (all the atom names here follow their crystallographic notations).13 In this study we consider allyl alcohol (CH2=CH-CH2-OH), proposed to coordinate to FeMoco as Fe6-η2(C=C) ferracycle product upon reductive binding of propargyl alcohol (CH≡C-CH2-OH),12-16 see Chart 1. Notably, in context of the Thorneley-Lowe kinetic scheme17 using EnHk notation for the nitrogenase catalytic intermediates, the allyl alcohol bound cofactor would be described as E4H4 state; here, n is the number of electrons and k is the number of protons delivered to the MoFe protein. The ‘electron inventory’ concept6 relates the number of electrons accepted by the MoFe protein from the Fe protein (n) to the net number of electrons that are delivered to FeMoco (m), plus those transmitted to the substrate (s), and also counting the electrons transferred to FeMoco from the P cluster (p): n + p = m + s. With the assumption that p = 0, we obtain n = 4 for the allyl alcohol bound FeMoco using m = 2 (2e− reduced FeMoco) and s = 2 (2e− required to reduce the propargyl alcohol substrate). Similarly, k = 4 results from the two protons delivered to FeMoco and two protons required to complete the reduction of the propargyl alcohol.

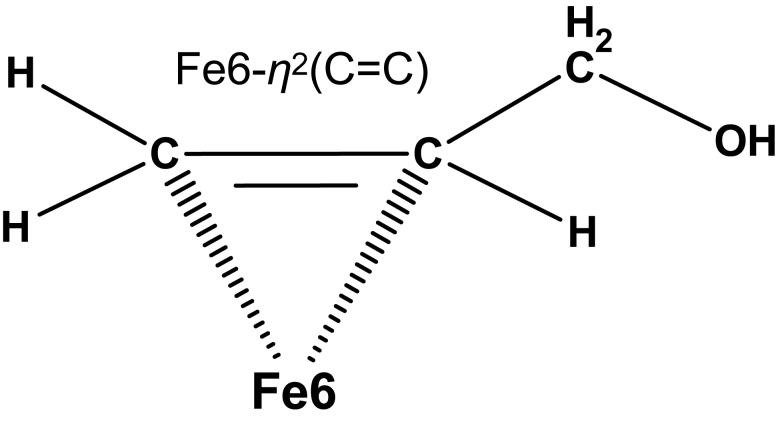

CHART 1.

Proposed Fe6-η2(C=C) ferracycle binding mode of allyl alcohol (CH2=CH-CH2-OH) at Fe6 of FeMoco.

Prior to introducing the ligand-bound complex, FeMoco spin couplings compatible with S = 1/2 and 2e− reduced oxidation level are considered in detail. We optimize three alternative conformations of allyl alcohol intermediate and predict the corresponding Aiso(X) values. Finally, the correlation between our calculated and 57Fe ENDOR experimental hyperfine parameters for the seven FeMoco iron sites is provided.

2. COMPUTATIONAL DETAILS

2.1. Modeling

Coordinates for the FeMoco structure were taken from the 1.16 Å resolution 1M1N PDB file.2 The structural model includes [Mo-7Fe-9S-X] core and its covalent ligands Cys275, His442, and R-homocitrate (HCA) (see Figure 1) simplified to methylthiolate, imidazole, and glycolate (−OCH2-COO−), respectively. While the X = N3− (also referred to as NX below) alternative was used for the interstitial atom, our results should qualitatively hold for X = C4−/O2− as well. The charge model corresponds to formal oxidation states [Mo4+3Fe3+4Fe2+] for the metals in the resting state of FeMoco, as proposed elsewhere.5,18 The 2e− reduced cofactor considered here would therefore correspond to [Mo4+1Fe3+6Fe2+] formal oxidation states, assuming that the molybdenum remains Mo4+ (see also Section 3.1). The sulfurs S2B and S3A (see Figure 1) were selected as protonation sites, in agreement with some recent studies favoring μ2S-H FeMoco protonations19,20 and our own earlier work.21 The ligand-bound FeMoco was constructed first placing allyl alcohol (CH2=CH-CH2-OH) at Fe6 (as Fe6-η2(C=C) ferracycle, see Chart 1) and then geometry-optimizing the complex. The starting geometry of the cofactor was intentionally perturbed to allow three different local minima, as discussed in Section 3.4 below.

2.2. Density Functional Methods

The calculations were done using the parameterization of electron gas data given by Vosko, Wilk and Nusair (VWN, formula version V)22 for the local density approximation (LDA), and the corrections proposed in 1991 by Perdew and Wang (PW91)23 for the generalized gradient approximation (GGA), as implemented in the Amsterdam Density Functional (ADF)24 package. During the geometry optimizations by ADF, triple-ζ plus polarization (TZP) basis sets were used for Fe and Mo metal sites, while double-ζ plus polarization (DZP) basis sets were used other atoms. The inner shells of Fe (1s22s22p6) and Mo (1s22s22p63s23p64s23d10) were treated by the frozen core approximation. Accurate single point wave functions, used to report the properties of the ligand-bound FeMoco state (relative energies, spin densities and spin populations, hyperfine couplings), were obtained using TZP basis set on all the atoms, with the frozen core used only for Mo as described above. Effects of the polar protein environment were considered using conductor-like screening model (COSMO)25 with the dielectric constant set to ε = 4.0.

2.3. Spin Coupling and Broken-Symmetry (BS) States

The FeMoco of nitrogenase includes eight metal sites, all of them potentially carrying unpaired electrons. For this type of system a set of the site spin vectors, satisfying a given set of metal oxidation states and a given total spin, is generally not unique. For the resting state FeMoco ([Mo4+3Fe3+4Fe2+], S = 3/2), ten spin alignments were constructed earlier10 (see Chart 2, BSx column) using a “simple” spin-collinear (“up” ↑ or “down” ↓) approach for three high spin ferric (Fe3+, d5, S = 5/2) and four high spin ferrous (Fe2+, d6, S = 2) sites. This approach yields all the spin alignments which bear ΣMSi = MS = St = 3/2 total FeMoco spin projection, implying that Fe site spin vectors Si are collinear with the total spin vector St, |MSi| = Si, i = 1…7. Notably, the [Mo-7Fe-9S-X] core possesses pseudo C3 structural symmetry around the rotational axis formed by the atoms Fe1, X, and Mo. Three rotamers for some of the spin alignments can be found. The presence of the covalent terminal ligands (Cys275, His442, HCA) to [Mo-7Fe-9S-X] results in small variations of these rotamer energies by ∼1 kcal/mol.10 When the protein environment is included as well (via continuum electrostatics approach), the rotamer energies are found to be split by ∼2 kcal/mol at most using our earlier modeling.26 We therefore consider only single rotamer for each spin alignment here. Because these spin orderings do not represent pure S = 3/2 spin states but rather broken-symmetry (BS) states,27 the nomenclature BS1 to BS10 was originally applied. We have now developed a utility code which generates BS states automatically. This utility takes user-defined number of spin sites and their types as input. For every site type, a set of its possible formal ionic charges Qi is given, and for every ionic charge a set of possible formal site spin projections MSi is defined. A programmed combinatorial search is then performed, with the two restraints set for the total charge (ΣQi = Qt) and total spin projection (ΣMSi = MS = St). We used this utility to address spin couplings for FeMoco at its 2e− reduced oxidation level, see Sections 3.1 below. Notably, application of our new utility confirmed that the set of formerly introduced spin couplings BS1 to BS1010 is complete for the resting state FeMoco; for the 2e− reduced FeMoco, new BS states were found, see Chart 2. When using ADF, a desired BS state was achieved first converging the ferromagnetic high-spin (7↑:0↓, HS) state (S = 31/2 for the resting, and S = 29/2 for the 2e− reduced state FeMoco), then exchanging α (↑) and β (↓) electron densities associated with the desired spin-down Fe atoms, and finally restarting the calculation. For both collinear and non-collinear spin states, the connection between the BS state spin density distribution and the hyperfine properties is provided by the spin coupling scheme and spin projection coefficients, see Equations 1-6 below. Unless specifically stated (see Section 3.1), all the BS states were geometry optimized using the methodology described above in Section 2.2.

2.4. Calculation of the Hyperfine Coupling Parameters

Electronic spin densities obtained from ADF28 were used to calculate hyperfine coupling A-tensors. The isotropic contribution AisoUBS to the calculated unrestricted broken symmetry (UBS) (‘raw’) A-tensor, also called the Fermi or contact interaction, is proportional to the point electron spin density, |ψ(0)|2 at the nucleus:

| [1] |

where St is the total electron spin of the system. In case of an X atom confined within [6Fe] prismane of FeMo-co, this “raw” result must be projected onto the total system spin. Quantitatively, this can be expressed as follows:29,30

| [2] |

where Aiso(X) is the calculated spin-coupled isotropic hyperfine parameter (which can be compared to experiment) and the sum runs over the six Fe ions adjacent to X. Here, Ki is a spin projection coefficient of the local Fe site spin Si onto the total FeMoco spin St:

| [3] |

The Ki to be used in Equation 3 were obtained applying spin projection chain and sum rules,10,29 Equations 4 and 5 below. The chain rule allows expressing Ki as the product of site spin projection coefficient onto a subunit spin, Kiq, and the subunit spin projection coefficient onto the total system spin, Kqt:

| [4] |

The sum rule states that the sum of the projection coefficients over all the sites is one:

| [5] |

Transition metal hyperfine parameters directly computed by DFT are generally known to be prone to error.31 For this reason, semiempirical calculations for the 57Fe site hyperfine couplings (Aicalc, see Table 1 and Table 2) were performed based on the following equation:30 where

| [6] |

P3d(Fei) is the calculated 3d Mulliken spin population of site i, and dB(Fei) = |P3d(Fei)|/2Si is the covalency factor, which is the ratio of the P3d(Fei) spin population to the 2Si maximum expected spin population in the valence-bond limit. dB(Fei) = 1 in the ionic limit, and decreases with increasing covalency, dB(Fei) < 1. For a given BS state, dB(Fei) ≥ 1 indicates an Si assignment inconsistent with the electronic structure; dB(Fei) values for some relevant structures of the present study are discussed in the text and listed in Table S3 of the Supporting Information. aionic in [6] is the intrinsic site hyperfine parameter for a purely ionic Fe, which depends on the Fe oxidation state:30

This procedure was originally developed to interpret iron hyperfine constants in iron-sulfur ([FeS]) clusters,30,32 and is expected to provide a good qualitative picture of how couplings from the individual sites are manifested in the experimental (coupled) spectrum. The quality of the semiempirical Fe hyperfine parameters can be assessed by considering the sum of the calculated Aicalc over all the sites, called atest:

| [7] |

For a number of [FeS] clusters, atest values in the range of −16 to −25 MHz were previously found.30 Values significantly outside of this range may be indicative of incorrect spin coupling.

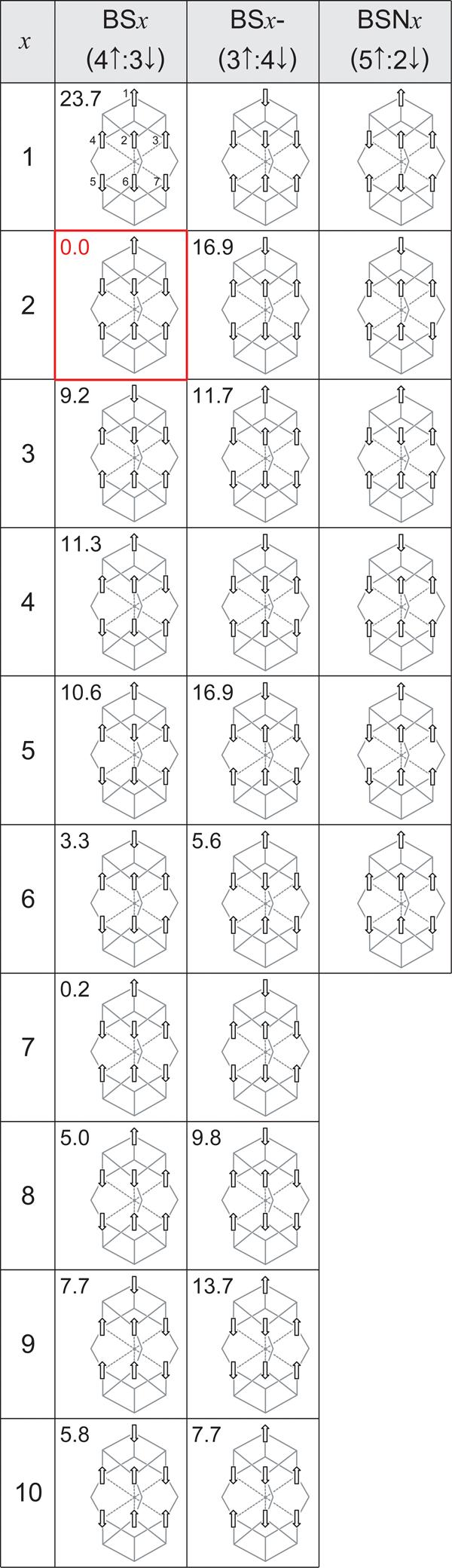

TABLE 1.

Assigned oxidation states, formal spin vector magnitudes Si, their projection values MSi, and calculated spin projection coefficients Ki for the seven Fe sites in 2e− reduced FeMoco.

| i | Oxidation state |

MSi = ±Si | Ki |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2+ | +2 | +12/11 |

| 2 | 2+ | −2 | −180/143 |

| 3 | 2.5+ | −9/4 | −405/286 |

| 4 | 2.5+ | −9/4 | −405/286 |

| 5 | 2+ | +2 | +22/15 |

| 6 | 2+ | +1* | +16/15 |

| 7 | 2+ | +2 | +22/15 |

| Sum | +1/2 | +1 |

exception: MSi ≠ Si = 2 for site i = 6 due to ‘canting’, see Section 3.2.

TABLE 2.

Calculated structural (Fei-NX internuclear distances), electronic (P(Fei) net electron spin populations), and semiempirical hyperfine (Aicalc) parameters of the seven Fe sites of FeMoco for allyl alcohol intermediate structures 1, 2 and 3 (see Figure 4). The electronic state is BS2 and the spin coupling is ‘canted’ at Fe6 (S6 = 2, MS6 = 1, see Figure 3). The matching experimental hyperfine coupling constants6 and their spectroscopic notations18 for the ethylene bound state SEPR1 are given in the last two columns.

| i | Fei-NX (Å)* |

P(Fei) (e) |

Aicalc (MHz) |

Aiexp |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | value (MHz) |

site type |

|

| 1 | - | - | - | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.8 | −27.1 | −25.4 | −26.2 | −23 to −26 | β4 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | −2.6 | −3.1 | −2.9 | 27.7 | 33.1 | 31.1 | 32 | α3 |

| 3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | −2.6 | −3.0 | −2.7 | 26.4 | 30.4 | 27.2 | 32 | α3 |

| 4 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | −2.7 | −2.7 | −2.4 | 27.7 | 27.9 | 24.6 | 32 | α3 |

| 5 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.1 | −32.3 | −27.5 | −25.8 | −33 | α4 |

| 6 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 2.0 | −9.9 | −26.9 | −18.2 | −18 | β3 |

| 7 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | −32.2 | −33.2 | −32.7 | −33 | α4 |

| Sum | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.6 | −19.7 | −21.6 | −20.0 | −11 to −14 | ||||

The reported Fei-NX distances precision is set to 0.1 Å in order to simplify their comparison (higher precision structural data is available from the Supporting Information).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The organization of this section is as follows. We first consider the electronic structure of the ligand-free 2e− reduced FeMoco using BS-DFT approach (with no μ2S cluster sites protonated at this stage). Spin alignments compatible with S = 1/2 and 2e− reduced oxidation level are constructed and assessed by their relative energies. Using the selected BS state, a spin coupling model in 2e− reduced FeMoco is developed. Based on the ligand-free electronic structure, we then construct and optimize three alternative local minima of the allyl alcohol intermediate. The interstitial atom hyperfine coupling parameter, Aiso(X), is calculated for X = 14N in all the intermediate alternatives. We then provide further justification of our results comparing the calculated semiempirical Fe hyperfine parameters to the relevant 57Fe ENDOR data. Finally, we test three alternative BS states for each of the three local minima of the ligand-bound FeMoco.

3.1. Fe Spin Alignment in 2e− reduced FeMoco

Combined analysis of 95,97Mo ENDOR and Mo EXAFS data suggests that the molybdenum is spinless in 2e− reduced FeMoco.33 Our results on the ligand-bound FeMoco species 1-3 considered below in Section 3.3 show that the calculated Mo spin densities correspond to approximately half of the unpaired electron based on the Mulliken spin populations, see Table S4. While this can be interpreted as mixed oxidation state molybdenum between Mo4+ (d2, S = 0) and Mo3+ (d3, S = 1/2). If Mo4+ oxidation favored by the experiment is assumed, only the seven iron sites would participate in spin coupling for both resting ([Mo4+3Fe3+4Fe2+], S = 3/2) and 2e− reduced ([Mo4+1Fe3+6Fe2+], S = 1/2) FeMoco states. Since the three irons (Fe5, Fe6, and Fe7) spin vectors neighboring to Mo are large, the effect of transferring 1e− to Mo4+ from Fe2+ and then antiferromagnetically coupling Mo3+ (S = 1/2) to Fe3+ (S = 5/2 or 3/2) will not change the overall spin coupling picture significantly.

For the resting state, there are only ten “simple” collinear spin alignments satisfying formal [Mo4+3Fe3+4Fe2+] oxidation states for the metals and MS = 3/2 when constraining the Fe sites to high-spin (ferric Fe3+, d5, S = 5/2 and ferrous Fe2+, d6, S = 2), see Section 2.3 and Chart 2. Notably, all the ten BSx states, x = 1…10, have a 4↑:3↓ spin coupling pattern. In 2e− reduced [FeS] clusters, ferric Fe3+ site is often considered as a part of 2Fe2.5+ mixed-valence pair.33 The 2e− reduced state FeMoco valencies can then be reformulated as [Mo4+2Fe2.5+5Fe2+]. For a Fe2.5+ site, the formal high spin is given as S = ½ (2 + 5/2) = 9/4, which is the average between S = 2 of Fe2+ and S = 5/2 of Fe3+. Our automated procedure (see Section 2.3) predicts that for [Mo4+2Fe2.5+5Fe2+], no BS states with total MS = 1/2 can be found when accepting only collinear high-spin mixed-valence (2Fe2.5+, S = 9/2) and ferrous (Fe2+, S = 2) sites. The combinatorial search satisfying ΣMSi = MS = St = 1/2 is successful only if at least one Fe2+ site spin vector projection becomes MSi = 1. This can be achieved if the corresponding ferrous site is (i) high-spin ‘canted’, so that Si and St vectors are no longer collinear or (ii) converted into the true intermediate spin Si = 1. Three subsets of BS states were found for the 2e− reduced FeMoco, see Chart 2: (i) the ten “classic” BS states, accessible if one MSi = 1 Fe2+ site is present; (ii) ten inverted 3↑:4↓ BS states (named BS1- to BS10-, “-“ for inverted), allowed if two MSi = 1 Fe2+ sites are present; (iii) finally, six new 5↑:2↓ BS states (named BSN1 to BSN6, “N” for new), requiring five MSi = 1 Fe2+ sites. Notably, decomposing the mixed-valence 2Fe2.5+ into Fe3+ + Fe2+ pair and considering whole [Mo4+1Fe3+6Fe2+] valencies instead produces the same set of BS states.

The relative energies within each BS subset (BSx, BSx-, or BSNx) are largely influenced by the number of antiferromagnetic interactions between the μ2S and μ3S sulfur-bridged Fe pairs, as noted before for the resting FeMoco state.10 The number of the formal intermediate spin projection MSi = 1 ferrous sites is, however, different in the three BS subsets, and grows in line BS (1) → BS- (2) → BSN (5), which introduces another factor in relative energies. BS- states were found to be typically higher in energy than ‘classic’ BS states (these two subsets however overlap on the energy scale, see Chart 2). We were unable to converge any of the six BSN states, probably due to the significant instability of this subset. All attempts to achieve DFT solution for a 5↑:2↓ coupling (after exchanging α (↑) and β (↓) electron densities as described in Section 2.3) resulted in either BS (4↑:3↓) or BS- (3↑:4↓) states. The convergence of BSx- states is not trivial as well: no solutions for BSx- numbers x = 1, 4, and 7 were found. The final result is that for S = 1/2 2e− reduced FeMoco, BS2 coupling gives the lowest energy (≡0.0 kcal/mol) with BS7 only 0.2 kcal/mol less stable, see Chart 2. The accuracy of the modern DFT methods does not allow us to discriminate between BS2 and BS7 based on such a small energies difference only; in Sections 3.4 and 3.5 below we provide additional arguments favoring BS2 vs. BS7.

Our comparative result on BS, BS-, and BSN relative energies is in good agreement with a recent DFT study19 which used a two-component spinor description of the wave function (nonbiased to conventional collinear spin calculations). In this study, it was found that noncollinear spin arrangements in FeMoco result in energetically unfavorable states. Alternatively, BS- and BSN subsets provide a larger number of true intermediate (S = 1) or low (S = 0) spin ferrous sites than BS, while the high-spin (S = 2) Fe2+ is generally favored in the tetrahedral coordination environment of iron-sulfur ([FeS]) clusters.34

3.2. Spin Coupling and Projection Coefficients

Fe spin-projection coefficients Ki (see Section 2.4) must be obtained in order to calculate hyperfine parameters. Spin-projection coefficients have been calculated earlier for [Mo4+1Fe3+6Fe2+], S = 3/2, BS610 and recently for [Mo4+3Fe3+4Fe2+], S = 3/2, BS7.8 Analogous approach is applied below for the 2e− reduced FeMoco core [Mo4+1Fe3+6Fe2+], S = 1/2, BS2. To use this approach, tentative Si values for the seven Fe centers must be assigned first.

There is high degree of spin delocalization in FeMoco, as confirmed by generally homogeneous P(Fei) iron Mulliken spin populations, i = 1…7. There is also non negligible spin transfer from irons to other atoms, see Table S4 of the Supporting Information section. This is confirmed by deviations of the P(Fei) sum from 1 (corresponding to one net unpaired electron for S = ½), see Table 2, and deviations of the covalency factors dB(Fei) from 1, see Table S3. Spin delocalization and transfer preclude us from assigning site charges and spins based only on P(Fei) values. The two following guidelines were used to do the assignment for the Fe sites: (i) to comply with BS2 coupling, MSi = 1 is necessary for at least one of the ferrous sites (see above in Section 3.1); here we choose to place the MSi = 1 spin vector at Fe6 which is the unique ligand-binding site and might be the subject to spin “canting” (S6 = 2, MS6 = 1) or intermediate spin (S6 = 1, MS6 = 1) (ii) if only one MSi = 1 ferrous site is allowed, 2Fe2.5+ mixed-valence pair spin vectors must be antiparallel to the total spin vector, as follows from the combinatorial search; for BS2 this implies that the two Fe2.5+ sites are among the three spin-down (↓) Fe numbers 2, 3, and 4; Fe3 and Fe4 were presently selected. The four remaining sites (i = 1, 2, 5, 7) are then high-spin ferrous. We used a coupling model where spin vectors are generally collinear (not ‘canted’), so that adding spins SA and SB would yield either SAB = SA + SB or |SA − SB|. The main coupling model however involves ‘canting’ at the single Fe6 site (S6 = 2, MS6 = 1), see the list of Fe spins Si in Table 1; an alternative Si assignment does not involve ‘canting’ at Fe6 but requires its conversion into the intermediate spin (S6 = 1, MS6 = 1) ferrous site, see Table S1 of the Supporting Information section. The graphic representation showing the nested structure of the current spin coupling model is given in Figure 3. To derive the spin-projection coefficients Ki, spin projection chain (Equation 4) and sum (Equation 5) rules were applied to our coupling model. The resultant Ki values for the main spin assignment (S6 = 2 case) are given in Table 1, and for the alternative assignment (S6 = 1 case) in Table S1. According to Equation 2, the scaling factor for the central X atom isotropic hyperfine Aiso(X) is then PX = 0.32 for the main spin assignment, and PX = 0.36 for the alternative.

FIGURE 3.

The presently used nested spin vector coupling model for the seven Fe sites in 2e− reduced FeMoco. Fe sites numbering is given. The two options for the Fe6 site spin S6 = 2 (main assignment, “canting” at Fe6) and S6 = 1 (alternative assignment, intermediate spin at Fe6) are considered.

3.3. Allyl Alcohol binding Modes at FeMoco and Aiso(X)

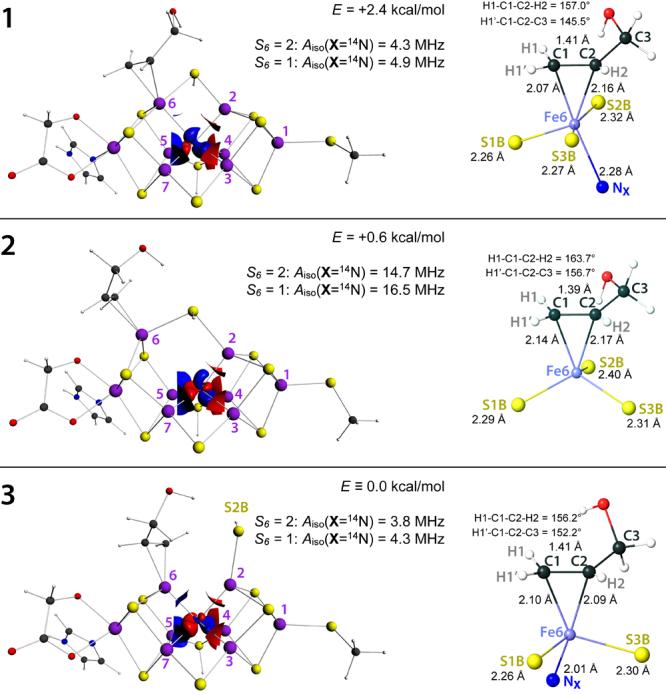

Alkyne species were proposed to bind reductively at Fe-2,3,4,7 face of the [6Fe] prismane, most probably at Fe6, resulting in Fe6-η2(C=C) ferracycle,13-16 see Section 1 and Chart 1. Even when limited to Fe6-η2(C=C) coordination, multiple configurations are available for allyl alcohol bound FeMoco, depending on the relative orientation of the ligand and the cofactor, as well as FeMoco conformation itself.15 Using the methodology described above in Section 2.2, we have analyzed three local minima (named 1, 2, and 3) for allyl alcohol Fe6-η2(C=C) coordination at FeMoco, see Figure 4. The C=C bond of the allyl alcohol was initially placed on the extension of the Fe6-X bond, perpendicular to it. The ligand was rotated around Fe6-X axis in a manner to receive the most stabilization from Allyl-OH⋯S2B hydrogen bonding. This type of alkene coordination at FeMoco approximately persisted through the geometry optimizations, and has been considered as favorable by a recent combined DFT and molecular mechanics (MM) study.13 We will first assume that [Mo-7Fe-9S-X] core electronic structures of a ligand-bound and (hypothetic) non-bound 2e− reduced cofactor states are similar (see also Section 1), so that they will share the same lowest energy spin coupling of the Fe sites. BS2 spin alignment, shown to be the most favorable in Section 3.1 above, was therefore used for the intermediate. A limited test of this assumption is provided in Section 3.5 below.

FIGURE 4.

DFT optimized model structures of allyl alcohol bound at Fe6 of FeMoco (2e− reduced state; μ2S sulfurs S2B and S3A are protonated), illustrating electronic (1), structural (2), and complex (3) perturbation of the [6Fe] symmetry. The relative energies are reported. The calculated isotropic hyperfine couplings Aiso(14NX) for the interstitial X = 14N atom are given for the two options of the Fe6 site spin: S6 = 2 (main assignment, “canting” at Fe6) and S6 = 1 (alternative assignment, intermediate spin at Fe6), see Figure 3. Point spin density isosurfaces inside the [6Fe] cage are shown using ρ = ±0.005 a.u. isovalues. The coordination sphere of the Fe6 site is shown in detail, with Fe6-ligand distances reported. H1-C1-C2-H2 and H1'-C1-C2-C3 dihedral angles illustrate deviation of the bound ethylene fragment from the planar conformation.

Notably, spin populations of the Fe6-bound alkene carbon atoms were found to be small, |P(Ci)| < 0.1e (i =1, 2, see Figure 4) for the intermediate alternatives 1-3 considered below, and this observation favors Fe6-C π-(C=C) vs. σ-(C) bonding assignment. C1-C2 bond lengths of 1.41/1.39/1.41 Å obtained for 1/2/3, see Figure 4, are closer to alkene C=C (1.34 Å) than to alkane C-C (1.54 Å) carbon-carbon bond length limit, which would again favor π-(C=C) bonding. There is, however, some degree of pyramidalization of the bound ethylene fragment which can be characterized measuring H1-C1-C2-H2 and H1'-C1-C2-C3 dihedral angles (see Figure 4), which are both equal to 179° in the optimized non-bound allyl alcohol, while H1-C1-C2-H2 = 157.0/163.7/156.2° and H1'-C1-C2-C3 = 145.5/156.7/152.2° were obtained for structures 1/2/3. In summary, the geometric parameters of the Fe6-η2(C=C) fragment are consistent with synergic bonding situation where the carbon atoms hybridization is somewhat between sp2 (corresponding to π-(C=C) bonding) and sp3 (corresponding to σ-(C) bonding), with more preference to sp2. The three ferracyclic bonding distances we obtained for the Fe6-η2(C=C) fragment (see Figure 4) are very similar to those experimentally determined for Pt-η2(C=C) fragment in the classic olefin-metal complex, Zeise's salt (K[PtCl3(C2H4)]·H2O): C1-C2 = 1.44 Å, Pt-C1 = 2.16 Å, Pt-C2 = 2.15 Å.35

The native FeMoco conformation is retained in the first considered structure 1 of Fe6-η2(C=C) alkene coordination. The [6Fe] prismane structure in 1 is well retained, with only moderate elongation of Fe6-NX by 0.3 Å with respect to the rest of Fei-NX = 2.0 Å, i = 2…7, in [6Fe], see Table 2. The coordination of Fe6 in 1 can be considered as either pseudo trigonal bypyramidal (C=C fragment and NX as axial, and S1B, S2B, S3B as equatorial ligands) or distorted octahedral, see Figure 4. This Fe6 coordination is different from the rest of the tetrahedral Fe sites in 1. The difference in the coordination types causes inhomogeneity in spin populations: P(Fe6) = 1.1e vs. the remaining irons which all bear |P(Fei)| ≥ 2.6e (Table 2). As previously proposed,6 the dative π-(C=C) bonding here might yield intermediate- or low-spin Fe. The calculated P(Fe6) = 1.1e likely corresponds to MS6 = 1 which can be achieved via (i) canting of the high-spin S6 = 2 ferrous site or (ii) its conversion into the true intermediate spin S6 = 1. 1 is therefore an intermediate where largely the electronic (not structural) symmetry of the [6Fe] prismane is perturbed. The outcome of this perturbation is Aiso(14NX) = 4.3 MHz in the case of canting and Aiso(14NX) = 4.9 MHz in the case of the intermediate Fe6 spin (the spin projection factors used for Aiso(X) are PX = 0.32 (S6 = 2) and 0.36 (S6 = 1), correspondingly, see Section 3.2).

The FeMoco core is plastic and a Fe-NX bond can be elongated significantly without a severe energetic penalty.15,19 In the second optimized local minimum 2, the coordination of NX to Fe6 is lost: Fe6-NX= 3.4 Å as compared to Fe-NX ≤ 2.0 Å for the rest of the prismane irons. In contrast to 1, Fe6 remains tetrahedral high-spin in 2, exchanging the NX ligand trans with the alkene, and P(Fei) spin populations are relatively homogeneous. It is therefore primarily the structural [6Fe] symmetry perturbation, which yields a large predicted Aiso(14NX) = 14.7 MHz calculated for 2 (using the spin projection factor PX = 0.32).

In line with a proposal that protonated μ2S-H bridge opening at the substrate binding Fe site will facilitate the reduction,19,36 Fe6-S2B coordination is no longer present in the third optimized conformation 3 of the allyl alcohol intermediate. There are no such prominent Fe-NX or P(Fe) variations within [6Fe] obtained for 3 as those described above for 1 and 2. Aiso(14NX) = 3.8 MHz calculated for 3 (using the spin projection factor PX = 0.32) can therefore be considered as the result of combined electronic and structural [Fe6] symmetry perturbation.

The three modes of allyl alcohol binding to FeMoco considered above were found nearly equienergetic. The order of the preference between the three local minima is as follows: 3 (≡0.0 kcal/mol), followed by 2 (+0.6 kcal/mol) and then by 1 (+2.4 kcal/mol). With such small energy differences for the present models, any of the above cofactor conformations may be found in the actual protein.

3.4. Fe Hyperfine Couplings

An alternative approach to discriminate between the three local minima 1-3 is to compare their semiempirical iron hyperfine parameters to the available 57Fe ENDOR values of SEPR1 state. We find SEPR1 relevant for the comparison because, like 1-3, this FeMoco state presumably carries Fe6-η2(C=C) fragment. Using the derived Ki spin projection coefficients (Section 3.2), semiempirical Fe isotropic hyperfine couplings Aicalc for allyl alcohol bound states 1, 2, and 3 are calculated via Equation 6 and provided in Table 2. Four types of Fe sites were reported for SEPR1 by 57Fe ENDOR, with ±1 MHz uncertainty in Aiexp isotropic hyperfine couplings: (i) α3, |Aiexp| = 32 MHz; (ii) α4, |Aiexp| = 33 MHz; (iii) β3, |Aiexp| = 18 MHz; (iv) β4, |Aiexp| = 23 to 26 MHz.6 The structural and electronic symmetry of the allyl alcohol bound FeMoco suggests a distribution of the seven Fe sites into four groups: (i) i = 1, unique terminal Fe coordinating Cys275; (ii) i = 2, 3, 4, the only spin-down Fe sites in BS2; (iii) i = 5, 7, spin-up Fe sites in BS2 not binding the ligand; (iv) i = 6, the only ligand-binding Fe site. Here we infer that, due to the pseudo three-fold rotational symmetry of BS2 FeMoco shown in Chart 2, Fe numbers 2, 3, and 4 can be clustered into the group of three equivalent sites; the ligand binding at Fe6 presumably results in splitting of the symmetry cluster arranged from Fe numbers 5-7 into two groups, 5 & 7 and 6.

The occurrence of only four distinct Fe hyperfine signals in SEPR1 is likely to impose selection rules on the possible allyl alcohol intermediate BS states. In Section 3.1 above (and Section 3.5 below) we find that BS2 and BS7 energies differ insignificantly and we need to provide additional arguments to discriminate between these states. Consistent with the ENDOR results, Fe sites of BS2 can be separated into the four groups, as discussed in the previous paragraph. Using the similar approach for analyzing BS7, five groups of spectroscopic sites are expected, because the group of Fe sites 2, 3, 4 equivalent in BS2 (all three spin-down) would now be split into two groups, 2 & 4 (spin-up) and 3 (spin-down) in BS7. For the ligand-bound FeMoco, this argument favors spin alignment BS2 vs. BS7.

In Table 2, we provide the match between the above four groups of SEPR1 experimental Aiexp and our calculated Aicalc isotropic hyperfine couplings. Notably, the signs for Aiexp must be deduced from the spin coupling model because only the absolute values of hyperfine couplings can be obtained by ENDOR. In line with the previous approach,6 we will restrict ourselves to assignments where only positive or only negative values are used for every observed type of Aiexp.

While atest = −11 to −14 MHz for the present assignment of SEPR1 57Fe ENDOR |Aiexp| data (measuring the quality of the Fe hyperfine values, see Section 2.4) is slightly outside of the −16 ≤ atest ≤ −25 MHz expected range, reasonably good overall fit was obtained. Notably, atest values (obtained from the computed Aicalc, i = 2…7, see Table 4) for the three local minima 1/2/3 are −19.7/−21.6/−20.6 MHz, correspondingly, which is in the middle of the expected atest range. The major difference between Aicalc value sets for structures 1-3 is observed at the Fe6 ligand-binding site: −9.9 MHz for 1, −26.9 MHz for 2, and −18.2 MHz for 3. |Aiexp| = 18 MHz assigned to Fe6 β3 site apparently favors structure 3 of the allyl alcohol intermediate. An alternative assignment of |Aiexp| values, exchanging β3 and β4 sites between Fe1 and Fe6 (see Table 2), would favor structure 2 with Aiexp = −23 to −26 MHz (β4) for Fe6. However, this would produce much worse correspondence between Aicalc and |Aiexp| at the terminal Fe1 site, for which our calculated values are in the −25.4 to −27.1 MHz range, and the experimental value of the alternative assignment would be −18 MHz (β3). Structure 1 has a very low A6calc = −9.9 MHz value resulting from the corresponding low covalency factor at Fe6, dB(Fe6) = 0.27. In summary, Fe hyperfine properties analysis for the coupling where Fe6 ferrous spin is ‘canted’ (S6 = 2, MS6 = 1) is most consistent with the following order of preference between the three local minima: 3, followed by 2, and then by 1.

Consideration of an alternative spin coupling model where Fe6 converts to the intermediate spin (S6 = 1 vs. ‘canted’ S6 = 2, see Sections 3.2 and 3.3) would actually favor structure 1 of the Fe6-η2(C=C) intermediate. Only this local minimum passes the covalency factor test (dB(Fei) < 1, see Section 2.4) for Fe6. Only for 1 does intermediate spin at Fe6 yields a reasonable hyperfine A6calc = −14.8 MHz, see Table S2. For 2 and 3, the calculated covalency factors are dB(Fe6) = 1.48 and 1.00, correspondingly, see Table S3. Via Equation 6, large dB(Fe6) also results in A6calc = −40.4 and −27.3 for 2 and 3, correspondingly, which significantly deviate from the assigned Aiexp = −18 MHz, see Table S2. Moreover, atest < −30 MHz for all the three local minima when using the alternative coupling are too negative, when compared to atest = −11 to −14 MHz of the fitted 57Fe ENDOR values and also to −16 ≤ atest ≤ −25 MHz expected range.

One more alternative assignment for the Fe site hyperfine parameters accompanies the 57Fe ENDOR study of SEPR1 state.6 This assignment, largely based on the best fit of −17 to −20 MHz to atest, is as follows: (i) α3, Aiexp = −32 MHz, 1 × Fe2.5+; (ii) α4, Aiexp = −33 MHz, 1 × Fe2.5+; (iii) β3, Aiexp = 18 MHz, 4 × Fe2+; (iv) β4, Aiexp = −23 to −26 MHz, 1 × Fe2+. All Fe sites were proposed to be high-spin. According to Equations 3 and 6, spin-up sites correspond to negative Aicalc and spin-down sites correspond to positive Aicalc. The earlier assignment would therefore exhibit a 3↑:4↓ spin coupling of the seven FeMoco iron sites, called BS- state here. However, our present results favor 4↑:3↓ spin coupling (namely, BS2); as explained above, a 3↑:4↓ spin coupling is accessible for the 2e− reduced S = 1/2 cofactor only when at least two MSi = 1 (intermediate spin) or highly ‘canted’ Fe2+ sites are present.

3.5. Alternative Spin Couplings for the Ligand-Bound States

Allyl alcohol binding in structures 1-3 provides a substantial electronic and structural perturbation to the [Mo-7Fe-9S-X] core, as reflected in Table 2 and Figure 4. Tentative usage of BS2 spin coupling for states 1-3 in Section 3.3 above thus needs additional justification: while we show that BS2 is the lowest energy state for the free 2e− reduced FeMoco (see Section 3.1 and Chart 2), alternative spin couplings might be preferred when a ligand binds at Fe6. In order to avoid an excessive umber of calculations, we provide a limited exploration of the ‘BS space’ for structures 1-3: only the three most stable spin couplings, as obtained from the free 2e− reduced FeMoco analysis, will be considered. These couplings are BS2 (≡0.0 kcal/mol), BS7 (0.2 kcal/mol), and BS6 (3.3 kcal/mol). The relative energies for the resulting optimized nine states (3 structures × 3 spin couplings = 9 states) are compared in Tables S5a-c. From Table S5b it can be deduced that, for all the three spin couplings considered, local minimum 3 remains more stable than 1 or 2. Table S5c shows that BS2 is the most stable spin coupling for local minima 1 and 2; for 3, BS7 is the most stable coupling, with BS2 only 1.6 kcal/mol above BS7. In summary, for allyl alcohol bound FeMoco species, the above results support (i) structure 3 as the most stable local minima and (ii) BS2 and BS7 as the generally most preferred spin couplings based on the relative energies.

Calculated central atom hyperfine parameter Aiso(14NX) for the above nine states, see Table S6, all show significant increase as compared to the resting state Aiso(14NX) = 0.3 MHz value obtained earlier.8 For the three alignments BS2, BS6, and BS7, the observed trend in magnitude of Aiso(14NX) is increase in the 3 < 1 < 2 line. For simplicity, when calculating X hyperfine value for BS6 and BS7 alignments, we used the same spin projection factor PX = 0.32 as derived below in Section 3.2 for BS2.

4. CONCLUSIONS

BS-DFT calculations have been used to address the 2e− reduced state of FeMoco cofactor of nitrogenase. The calculations provide а framework for understanding the [Mo-7Fe-9S-X] core electronic structure in freeze-trapped S = 1/2 paramagnetic states observed upon various ligands coordination to FeMoco.

We have used a new combinatorial approach that generates all the possible spin configurations of the metal sites (BS states) compatible with their given bulk oxidation level and total spin. For 2e− reduced S = 1/2 FeMoco, we show that ten 4↑:3↓, ten 3↑:4↓, and six 5↑:2↓ spin couplings of the seven Fe sites are available (Chart 2). Combined consideration of the relative energies, FeMoco symmetry, and comparison of the calculated vs. experimental Fe hyperfine parameters favor BS2 (one of the 4↑:3↓ couplings) as the most appropriate spin alignment from the BS pool.

The three local minima 1-3 (Figure 4) considered for the allyl alcohol intermediate all share Fe6-η2(C=C) ferracycle mode of the ligand binding (Chart 1), where Fe6-C π-(C=C) bonding character was found to prevail over σ-(C). 1, 2, and 3 illustrate the following three types of [6Fe] FeMoco iron prismane perturbation (Table 2): (i) minor structural effects, but significant electronic influence on the Fe6 spin state in 1; (ii) dissociation of the Fe6-X bond in favor of the Fe6-ligand bond trans to it, with little change of the Fe6 spin state in 2; (iii) opening of the protonated μ2S2B-H bridge from the Fe6 side, introducing moderate level of both structural and electronic perturbation in 3. Calculated relative energies and iron hyperfine parameters suggest that 3 is the most favored binding mode, followed by 2, and then by 1.

The comparison of the BS-DFT semiempirical vs. 57Fe ENDOR experimental Fe hyperfine coupling parameters for the Fe6-η2(C=C) intermediate supports the spin coupling where the ligand-binding Fe6 site is ‘canted’ high-spin (S6 = 2, MS6 = 1) ferrous ion (see Tables 1 and 2); A6calc = −18.2 MHz (for the allyl alcohol binding mode 3) is then in the good agreement with the smallest |Aiexp| = 18 MHz reported for SEPR1 (which is FeMoco freeze-trapped spectroscopic state with C2H4 bound). An alternative spin coupling model assigning true intermediate spin to Fe6 (S6 = 1, MS6 = 1) would pass the Fe6 covalency factor test (dB(Fei) < 1, see Section 2.4) only for structure 1 among the three alternatives analyzed. While the corresponding A6calc = −14.8 MHz is reasonable, S6 = 1 assignment results in too negative atest < −30 MHz (see Table S2) values for all the three allyl alcohol binding modes.

One further extension of our study is the analysis of the hyperfine parameters for allyl alcohol atoms when bound to the S = 1/2 cofactor. The experimental 13C and 1,2H ENDOR characterization for this FeMoco ligand is already available.14 Our preliminary results are that the ligand hyperfine parameters are significantly sensitive to (i) the ligand orientation relatively to FeMoco and (ii) hydrogen bonding to the ligand atoms from the protein environment. The reported pH-dependence of the allyl alcohol intermediate EPR signal intensity was interpreted in favor of the hydrogen bonding between the protonated His195 imidazole and allyl-OH oxygen.12,13 BS-DFT calculations incorporating His195 into the model are in progress.

A major conclusion of the present study is that coordination of a ligand at one of the [6Fe] prismane irons most likely perturbs the symmetry in such a way that Aiso(X) increases at least one order of magnitude (Aiso(14NX) = 4.3/14.7/3.8 MHz for structures 1/2/3, correspondingly), as compared to the ligand-free resting state FeMoco (Aiso(14NX) = 0.3 MHz, see Section 1). Shown for X = N, this trend is likely to be qualitatively correct for other X alternatives C and O. In summary, certain ligands coordinating to FeMoco are expected to generate X hyperfine signal large enough to be detected, and differentiated from the protein atoms, by techniques such as ENDOR and ESEEM. An experimental examination of this computational result, capable of casting light on the identity of X, is anticipated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the financial support by NIH Grant GM39914 (to D.A.C. and L.N.). We thank E. J. Baerends for ADF codes, W.-G. Han for computational assistance, and B. M. Hoffman for valuable discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available:

The details of the alternative spin coupling, covalency factors for the Fe sites, net electron spin populations for the non-iron FeMoco core atoms, relative energies and Aiso(X = 14N) values for the allyl alcohol bound FeMoco structures 1-3 in BS2, BS6, and BS7 spin alignments, and optimized XYZ coordinates for 1-3. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Shah VK, Brill WJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1977;74:3249–3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rawlings J, Shah VK, Chisnell JR, Brill WJ, Zimmermann R, Munck E, Orme-Johnson WH. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:1001–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Einsle O, Tezcan FA, Andrade SL, Schmid B, Yoshida M, Howard JB, Rees DC. Science. 2002;297:1696–700. doi: 10.1126/science.1073877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard JB, Rees DC. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:17088–17093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603978103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinnemann B, Norskov JK. Topics in Catalysis. 2006;37:55–70. [Google Scholar]; Dance I. Inorganic Chemistry. 2006;45:5084–5091. doi: 10.1021/ic060438l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cao ZX, Jin X, Zhang QN. Journal of Theoretical & Computational Chemistry. 2005;4:593–602. [Google Scholar]; Huniar U, Ahlrichs R, Coucouvanis D. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:2588–2601. doi: 10.1021/ja030541z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hinnemann B, Norskov JK. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:3920–3927. doi: 10.1021/ja037792s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Vrajmasu V, Munck E, Bominaar EL. Inorganic Chemistry. 2003;42:5974–5988. doi: 10.1021/ic0301371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hinnemann B, Norskov JK. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:1466–1467. doi: 10.1021/ja029041g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dance I. Chemical Communications. 2003:324–325. doi: 10.1039/b211036a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovell T, Liu T, Case DA, Noodleman L. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8377–83. doi: 10.1021/ja0301572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee HI, Sorlie M, Christiansen J, Yang TC, Shao JL, Dean DR, Hales BJ, Hoffman BM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:15880–15890. doi: 10.1021/ja054078x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee HI, Benton PMC, Laryukhin M, Igarashi RY, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:5604–5605. doi: 10.1021/ja034383n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukoyanov D, Pelmenschikov V, Maeser N, Laryukhin M, Yang TC, Noodleman L, Dean DR, Case DA, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Inorganic Chemistry. 2007;46:11437–11449. doi: 10.1021/ic7018814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomann H, Morgan TV, Jin H, Burgmayer SJN, Bare RE, Stiefel EI. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1987;109:7913–7914. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lovell T, Li J, Liu TQ, Case DA, Noodleman L. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2001;123:12392–12410. doi: 10.1021/ja011860y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barney BM, Lee HI, Dos Santos PC, Hoffmann BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Dalton Transactions. 2006:2277–2284. doi: 10.1039/b517633f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dos Santos PC, Igarashi RY, Lee HI, Hoffman BM, Seefeldt LC, Dean DR. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2005;38:208–214. doi: 10.1021/ar040050z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Igarashi RY, Dos Santos PC, Niehaus WG, Dance IG, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34770–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HI, Igarashi RY, Laryukhin M, Doan PE, Dos Santos PC, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:9563–9569. doi: 10.1021/ja048714n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dance I. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:11852–11863. doi: 10.1021/ja0481070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dos Santos PC, Mayer SM, Barney BM, Seefeldt LC, Dean DR. J Inorg Biochem. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorneley RNF, Lowe DJ. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 1996;1:576–580. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo SJ, Angove HC, Papaefthymiou V, Burgess BK, Munck E. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2000;122:4926–4936. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kastner J, Blochl PE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2998–3006. doi: 10.1021/ja068618h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dance I. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6328–6340. doi: 10.1021/bi052217h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovell T, Li J, Case DA, Noodleman L. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:4546–4547. doi: 10.1021/ja012311v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vosko SH, Wilk L, Nusair M. Canadian Journal of Physics. 1980;58:1200–1211. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perdew JP, Chevary JA, Vosko SH, Jackson KA, Pederson MR, Singh DJ, Fiolhais C. Physical Review B. 1992;46:6671–6687. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.46.6671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velde GT, Bickelhaupt FM, Baerends EJ, Guerra CF, Van Gisbergen SJA, Snijders JG, Ziegler T. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2001;22:931–967. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pye CC, Ziegler T. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts. 1999;101:396–408. [Google Scholar]; Klamt A, Jonas V. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1996;105:9972–9981. [Google Scholar]; Klamt A. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1995;99:2224–2235. [Google Scholar]; Klamt A, Schuurmann G. Journal of the Chemical Society-Perkin Transactions. 1993;2:799–805. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovell T, Li J, Case DA, Noodleman L. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2002;7:735–749. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noodleman L. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1981;74:5737–5743. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Lenthe E, van der Avoird A, Wormer PES. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1998;108:4783–4796. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noodleman L, Peng CY, Case DA, Mouesca JM. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 1995;144:199–244. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mouesca JM, Noodleman L, Case DA, Lamotte B. Inorganic Chemistry. 1995;34:4347–4359. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaupp M, Bühl M, Malkin VG. Calculation of NMR and EPR parameters : theory and applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mouesca JM, Noodleman L, Case DA. Inorganic Chemistry. 1994;33:4819–4830. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee HI, Hales BJ, Hoffman BM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1997;119:11395–11400. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beinert H, Holm RH, Munck E. Science. 1997;277:653–659. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Black M, Mais RHB, Owston PG. Acta Crystallographica Section B-Structural Crystallography and Crystal Chemistry. 1969;B 25:1753. &. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kastner J, Blochl PE. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:4568–75. doi: 10.1021/ic0500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.