Abstract

The purpose of this study was to characterize the Night Eating Syndrome (NES) and its correlates among non-obese persons with NES, and to compare them to non-obese healthy controls. Nineteen non-obese persons with NES were compared to 22 non-obese controls on seven-day, 24-hour prospective food and sleep diaries, the Eating Disorder Examination and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Diagnoses interviews, and measures of disordered eating attitudes and behavior, mood, sleep, stress, and quality of life. Compared to controls, persons with NES reported significantly different circadian distribution of food intake, greater depressed mood, sleep disturbance, disordered eating and body image concerns, perceived stress, decreased quality of life, and more frequent Axis I comorbidity, specifically anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders. These findings are the first to describe the clinical significance of night eating syndrome among non-obese individuals in comparison to a non-obese control group, and they suggest that NES has negative health implications beyond that associated with obesity.

Keywords: night eating syndrome, eating disorders, sleep, mood, stress, clinical significance

1.0 Introduction

Night Eating Syndrome (NES) is concived as a delay in the circadian pattern of food intake (Stunkard, Grace, & Wolf, 1955). The original definition of NES, based on clinical observation of obese persons, operationalized the syndrome as evening hyperphagia (the consumption of ≥ 25% of total daily food intake after dinner), morning anorexia, and depressed mood that worsens in the evening (Stunkard, Grace, & Wolf, 1955). Since this definition was proposed, over 50 publications on the characterization and prevalence of NES have been presented. Naturally, as the circadian eating patterns of additional populations have been studied, the operational definition of NES has evolved (Birketvedt et al., 1999; O’Reardon et al., 2004). Currently, NES is operationalized as engaging in evening hyperphagia (consumption of ≥ 25% of total daily calories after completion of the evening meal) and/or nocturnal awakenings accompanied by ingestions of food (≥ 3 episodes/week) (Allison, Grilo, Masheb, & Stunkard, 2005). Morning anorexia and depressed mood that worsens in the evening are considered associated features of the syndrome (Engel, 2005).

NES was originally seen as a behavioral phenotype of obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m2); the earliest description of NES noted a prevalence of 64% among difficult to treat obese patients (Stunkard, Grace, and Wolf, 1955). Current research supports the association between NES and excess weight for some people. For example, we found (Lundgren et al., 2006) found that obese psychiatric outpatients were five times more likely than non-obese psychiatric outpatients to meet criteria for NES. Also, Andersen and colleagues (2004) found that obese women enrolled in the longitudinal Danish MONICA study who endorsed the question “do you get up at night to eat” gained significantly more weight over six years than did obese women who did not endorse the night eating question; no weight differences across time were found for men or non-obese women.

The association between NES and obesity has also been supported with prevalence estimates suggesting that NES is more common among obese persons (6–16%) (Ceru-Björk, Andersson, & Rössner, 2001; Adami, Campostano, Marinari, Ravera, Scopinaro, 2002) as compared to the general population (1.5%) (Rand, Macgregor, Stunkard, 1997).

Despite this elevated incidence among obese samples, not all persons with NES are obese or overweight (Marshall, Allison, O’Reardon, Birketvedt, & Stunkard 2004; Birketvedt et al., 1999; de Zwaan, Roerig, Crosby, Karaz, & Mitchell, 2006; Striegel-Moore, Franko, Thompson, Affenito, & Kraemer, 2006). Most literature has focused on obese night eaters1; Marshall and colleagues (2004), however, noted that 40 non-obese night eaters who completed an online version of the Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ; Allison et al., in press) responded similarly to obese night eaters who completed the NEQ online or in an outpatient clinic. No differences were found between non-obese and obese night eaters for morning appetite, evening hyperphagia, difficulty with sleep and mood, perceived need to eat in order to fall asleep, or cravings and control over eating in the evening and upon awakening in the middle of the night. The only differences were that non-obese night eaters were significantly younger and reported significantly more nocturnal awakenings and nocturnal ingestions of food.

Similarly, Birketvedt and colleagues (1999) found no differences between non-obese and obese night eaters on 24-hour circadian levels of melatonin, cortisol, blood glucose, and plasma insulin in an inpatient sleep and eating study. Plasma leptin levels, as expected, were lower among non-obese than among obese night eaters.

The limited number of studies describing NES among non-obese persons suggests that additional investigation among this group is warranted. For example, it is important to know if NES is a clinically significant syndrome among persons of all levels of body mass. This question can be approached in two ways: 1) comparing non-obese night eaters to obese night eaters and 2) comparing non-obese night eaters to non-obese healthy controls. In the former comparison, the impact of weight on abnormal circadian eating behavior can be examined; in the latter comparison, the effect of eating behavior on psychosocial functioning, when controlling for BMI, can be examined. The reports by Birketvedt and colleagues (1999) and Marhsall and colleagues (2004) have addressed the first approach. In this study we address the second approach, describing the nature and correlates of NES among non-obese night eaters in comparison to weight matched control group. We hypothesize that non-obese night eaters will differ significantly from nonobese healthy controls on circadian eating and sleeping patterns, disordered eating attitudes and behavior, mood and stress, quality of life, and psychiatric histories. In sum, we propose to establish the clinical significance of NES among non-obese persons.

2.0 Method

2.1 Participants

Nineteen non-obese night eaters (BMI < 25.0 kg/m2) and 22 non-obese controls enrolled in an outpatient study of the characterization of NES at the University of Pennsylvania. This study was reviewed and approved by the University Institutional Review Board. Demographic comparisons are presented in Table 1. Night eaters did not differ significantly from controls on age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, or BMI.

Table. 1.

Demographic comparison of Night Eaters and Controls

| Variable | Night Eaters N = 19 |

Controls N = 22 |

Statistic, Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years; M, sd) | 42.0 (15.5) | 36.5 (12.1) | t (39) = 1.3, p = 0.21 |

| Gender (% Female) | 84.2 | 86.4 | χ2(1) = 0.0, p = 0.85 |

| Ethnicity | χ2(3) = 4.8, p = 0.20 | ||

| % Caucasian | 94.7 | 81.8 | |

| % African American | 0.0 | 4.5 | |

| % Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.0 | 13.6 | |

| %Hispanic/Latino | 5.3 | 0.0 | |

| Marital Status | χ2(3) = 1.1, p = 0.75 | ||

| % Single | 47.4 | 54.5 | |

| % Married | 26.3 | 31.8 | |

| % Divorced/Separated | 21.1 | 9.1 | |

| % Widowed | 5.3 | 4.5 | |

| %High School Graduate | 100.0 | 100.0 | -- |

| BMI (m/kg2) (M, sd) | 22.5 (1.7) | 21.7 (1.9) | t (39) = 1.4, p = 0.17 |

2.2 Procedure

Participants with Night Eating Syndrome were recruited by television and newspaper advertisements seeking persons endorsing night eating behaviors. The ads asked for persons who were “troubled by overeating at nighttime,” and either ate at least a quarter of their daily food intake after dinner or woke up during the night to eat. Control participants were recruited from flyers posted in the Health System of the University of Pennsylvania asking for persons who did not overeat after dinner or wake up at night to eat. Exclusion criteria for both groups included: pregnancy, current night shift work, current participation in a weight reduction program or active attempts to lose weight, and diagnosis of diabetes, sleep apnea, current diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, lifetime history of bipolar disorder or psychotic disorder, substance abuse or dependence within the past three months or current major depression of greater than moderate severity as diagnosed on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Diagnosis (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, & Benjamin, 1996).

All participants were screened with the NEQ (Allison et al., in press), and the diagnosis of Night Eating Syndrome was made using the Night Eating Syndrome History and Inventory (NESHI; unpublished semi-structured interview) in conjunction with ten day, 24-hour prospective food and sleep records kept on an outpatient basis. The middle seven days of the food record were used in diagnosis and the statistical analyses; the first two days of the food record were considered practice and the last day included incomplete data.

Participants were given detailed instructions on the completion of the food record, and were provided measuring cups for home use. Participants were instructed to record the following for each eating episode, regardless of the time of day: the type and amount of food, details of the food preparation, brand name if a prepackaged food, and time of the eating episode. Participants recorded their sleep and wake times so that nocturnal eating episodes could be analyzed. Data collected from the food records were entered into Food Processor (ESHA Research, Salem, OR) by a registered dietician, and caloric intake data were used in the calculation of total daily calories, evening hyperphagia and frequency of nocturnal ingestions of food.

Participants were classified as NES positive if they reported evening hyperphagia (consumption of 25% or more of total daily food intake after supper until the final awakening the following morning) and/or nocturnal awakening and ingestion of food three or more times per week. To calculate the average percentage of evening hyperphagia, calories consumed after supper were divided by the total daily calories and were averaged across the seven days. Any food, but not liquid, consumption after a participant had reported falling asleep but before awakening the following morning was coded as a nocturnal ingestion of food.

Of the 19 persons diagnosed with NES, 16 met criteria for both evening hyperphagia and nocturnal awakening and ingestion of food, one met criteria for evening hyperphagia only, and two met criteria for nocturnal awakening with ingestion of food only. The absence of these behaviors was confirmed in the control participants.

The following additional assessments were conducted with all participants: Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993), Eating Inventory (EI; Stunkard & Messick, 1985), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, 1996), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983), Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (QLES-Q; Endicott, Nee, Harrison, & Blumenthal, 1993), Morningness-Eveningness Scale (ME; Smith, Reilly, & Midkiff, 1989), Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer,1989), and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS; Johns, 1994).

2.3 Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the overall circadian eating patterns of non-obese night eaters, including percentage of energy consumed (1) from commencement of dinner (defined as the evening meal) until awakening the next morning, (2) after dinner until awakening the next morning, (3) between dinner and bedtime, and (4) after bedtime until awakening the next morning. The number of nocturnal awakenings, nocturnal ingestions of food, and level of morning hunger are also described.

Using the average cumulative caloric intake data from 6:00 a.m. through 5:59 a.m. the following morning, we first derived the time (in hours) to intake of 75% of the total daily calories, and then examined the survival curves to 75% of caloric intake over the 24-hours. The Cox PHREG (Proportion Hazards Regression) procedure in SAS (Allison, 1995) was used to compare the curves between the NES and control groups. The PHREG procedure performs regression analyses of survival data, based on the Cox proportional hazards model (Cox & Snell, 1984). Cox’s semi-parametric model is widely used in the analysis of survival data to explain the effect of explanatory variables on survival times.

Independent samples t-tests and chi square tests were used to compare the groups on psychosocial variables assessed by surveys and interviews. Variables were theoretically grouped into families (Jaccard, 1990) as follows: (a) eating patterns (percentage of evening hyperphagia, nocturnal awakenings and nocturnal ingestions of food, morning hunger, and total daily energy intake), (b) eating attitudes (EDE, EI), and (c) mood, sleep, stress, and quality of life (BDI, PSS, ESS, PSS, ME, and QLES-Q). When t-tests were used, the Holm-modified Bonferroni correction controlled for experiment-wise error within each family of variables (Holm, 1979; Jaccard, 1990). The Holm method uses a variable adjusted alpha level. First, p values are ranked from smallest to largest. Next, the comparison with the smallest p value is evaluated at p = 0.05 / number of contrasts; the next smallest p value is evaluated at p = 0.05 / (number contrasts – 1). This adjustment continues until comparisons are no longer significant at the adjusted alpha level (Holm, 1979; Jaccard, 1990).

3.0 Results

3.1 Circadian Eating Patterns and NES Symptomatology

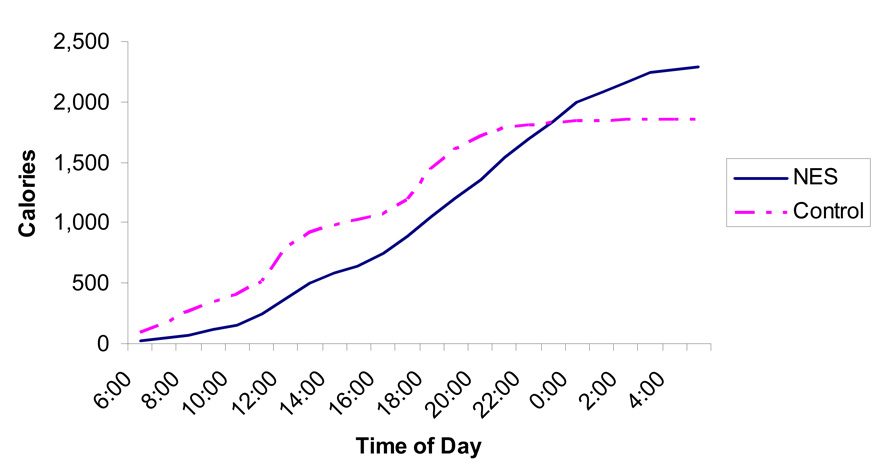

As Figure 1 shows, the pattern of cumulative caloric intake beginning at 6:00 a.m. and ending at 5:59 a.m. the following day differs greatly between night eaters and healthy controls. The night eater’s early intake is less than that of controls, and steadily increases throughout the day and into the night. Controls, however, show a small increase at breakfast time, the expected increases in cumulative caloric intake at traditional U.S. lunch and dinner times, and have a plateau in cumulative caloric intake around 10:00 p.m. At the end of the 24-hour period (5:59 a.m.) the night eaters had consumed significantly more total calories than had controls (night eater = 2284.5 ± 620.3 kcal; control = 1856.2 ± 545.2 kcal; t (39) = 2.5, p = 0.015).

Figure 1. Cumulative Daily Caloric Intakes for Night Eaters and Controls.

This figure shows the 7-day average cumulative daily food intake for night eaters and controls beginning at 6:00 a.m. and ending at 5:59 a.m. the following morning. Night eaters show a different circadian pattern of food intake and consume significantly more calories during the 24-hour period.

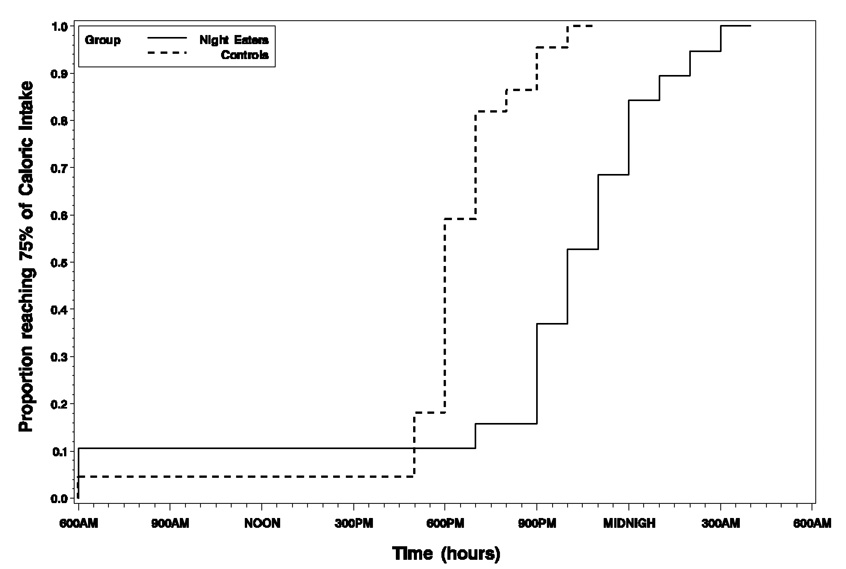

There was a statistically significant difference when comparing the time to 75% of caloric intake between the night eaters (median 17 hours; 11:00 p.m.) and the control group (median 13 hours; 7:00 p.m.), yielding a four hour delay for the night eaters (Chisquare = 17.2, p < 0.001). Although the hazard functions for night eaters and controls cross at approximately 5:00 p.m., there was no statistically significant evidence of a violation in the proportional hazards assumption (Chi-square = 1.04, p = 0.31). Figure 2 plots the survival curves to 75% of total cumulative intake for both groups.

Figure 2. Plot of survival curves to 75% of cumulative caloric intake for night eaters and controls.

This figure shows the survival curves to 75% of caloric intake over the 24-hours for night eaters and controls. Groups were statistically significantly different, with the median time to consumption of 75% of total daily intake at 11:00 p.m. for night eaters and 7:00 p.m. for controls.

In proportion to their total daily food intake, night eaters, compared to controls, reported significantly more evening and nocturnal food consumption. Table 2 shows the percentage of total daily caloric intake, averaged over 7 days, for the following: (a) from (including) dinner until awakening the next morning, (b) after dinner until awakening the next morning, (c) between dinner and bedtime, and (d) after bedtime until awakening the next morning. Also shown in Table 2, night eaters, compared to controls, reported significantly more nocturnal awakenings, nocturnal ingestions of food, and less morning hunger. All analyses, including the total cumulative caloric intake reported above, remained statistically significantly different after adjustment for experimentwise error.

Table 2.

Comparison of evening and nocturnal food intake for night eaters and controls.

| Variable | Night Eater M ± SD |

Control M± SD |

Statistic, Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dinner to awakening (% of TDCI) | 65.3 ± 13.9 | 41.6 ± 8.3 | t (39) = 6.8, p < 0.001 |

| After dinner to awakening (% of TDCI) | 49.8 ± 14.6 | 13.3 ± 11.8 | t (39) = 8.9, p < 0.001 |

| After dinner to bedtime (% of TDCI) | 32.2 ± 18.6 | 13.2 ± 11.8 | t (39) = 4.0, p < 0.001 |

| After bedtime to awakening (% of TDCI) | 17.9 ± 13.4 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | t (39) = 6.3 p < 0.001 |

| Nocturnal Awakenings per Week | 12.6 ± 8.3 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | t (39) = 6.1, p < 0.001 |

| Nocturnal Ingestions per Week | 9.6 ± 7.8 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | t (39) = 5.8, p < 0.001 |

| Morning Hunger before 1st meal (0–100) | 26.4 ± 24.3 | 58.0 ± 20.2 | t (35) = 4.3, p < 0.001 |

Note. Dinner refers to the evening meal, defined as the first meal initiated between 17:00 and 20:00 hrs. If no meal was eaten during this time on a given day, the average dinner time across the remaining days was taken, and any intake after that time was considered “after dinner”; TDCI = total daily caloric intake.

3.2 Eating Attitudes

Compared to controls, night eaters scored significantly higher on all subscales of the Eating Disorder Examination: Dietary Restraint, Weight Concern, Shape Concern, and Eating Concern (Table 3). Accordingly, they also scored higher than controls on the EDE global score. All analyses remained statistically significantly different after adjustment for experiment-wise error.

Table 3.

Comparison of night eaters and controls on eating attitudes and disordered eating behavior.

| Variable | Night Eaters N = 19 M ± SD |

Controls N = 22 M± SD |

Statistic, Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDE Subscales | |||

| Weight concern | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | t (1,39) = 5.5, p < 0.001 |

| Shape concern | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 0.3 ± 0.4 | t (1,39) = 6.1, p < 0.001 |

| Eating Concern | 1.5 ± 1.4 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | t (1,39) = 4.8, p < 0.001 |

| Dietary Restraint | 2.1 ± 1.6 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | t (1,39) = 5.5, p < 0.001 |

| Global Score | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | t (1,39) = 7.3, p < 0.001 |

| EDE Compensatory Behaviors | |||

| Days Intense Exercise | 5.4 ± 10.7 | 1.3 ± 5.1 | t (1,39) = 1.6, p = 0.12 |

| Days Vomit | 0.3 ± 1.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | t (1,38) = 1.4, p = 0.18 |

| Days Diuretic Use | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | -- |

| Days Laxative Use | 0.6 ± 2.4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | t (1,38) = 1.1, p = 0.27 |

| EDE Fear of Weight Gain | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | t (1,39) = 5.2, p < 0.001 |

| Eating Inventory (M, SD) | |||

| Cognitive Restraint | 12.6 ± 5.7 | 7.7 ± 3.7 | t (1,37) = 3.1, p = 0.004 |

| Disinhibition | 9.0 ± 4.0 | 3.3 ± 2.5 | t (1,38) = 5.4, p < 0.001 |

| Hunger | 6.9 ± 2.7 | 2.7 ± 2.3 | t (1,38) = 5.2, p < 0.001 |

Note. EDE = Eating Disorder Examination.

Because night eaters consumed significantly more total daily calories (approximately 400 calories) than controls, yet had the same BMI, compensatory behaviors and the fear of weight gain were analyzed, as measured on the Eating Disorder Examination. No significant differences were found for days of vomiting, laxative use, or diuretic use. Night eaters engaged in more days of intense exercise than did controls (5.4 days vs. 1.3 days), but this analysis did not reach statistical significance. Although groups were of similar BMI, night eaters endorsed higher levels of fear of weight gain than controls (Table 3). On the Eating Inventory, night eaters reported higher levels of Cognitive Restraint, Disinhibition, and Hunger than controls (Table 3). All Eating Inventory analyses remained significantly different after adjustment for experiment-wise error.

3.3 Mood and Stress, Quality of Life, and Sleep

Night eaters, compared to controls, reported more depressed mood and perceived stress and significantly lower quality of life; all remained significant after controlling for experiment-wise error. Mean scores and statistical analyses for the Beck Depression Inventory, Perceived Stress Scale, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Scale are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of night eaters and controls on mood, stress, quality of life, and sleep, and circadian preference.

| Variable | Night Eaters N = 19 |

Controls N = 22 |

Statistic, Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDI (M, sd) | 17.3 ± 11.9 | 2.2 ± 2.8 | t (1,39) = 5.7, p < 0.001 |

| PSS (10 item; M, sd) | 22.2 ± 9.1 | 10.7 ± 4.6 | t (1,38) = 5.1, p < 0.001 |

| QLES-Q (M, sd) | 47.7 ± 11.5 | 56.4 ± 6.7 | t (1,38) = 3.1, p = 0.003 |

| PSQ (M, sd) | |||

| Subjective Sleep Quality | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | t (1,38) = 7.1, p < 0.001 |

| Sleep Latency | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | t (1,37) = 5.5, p < 0.001 |

| Sleep Duration | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | t (1,37) = 2.7, p = 0.007 |

| Habitual Sleep Efficiency | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | t (1,36) = 4.6, p < 0.001 |

| Sleep Disturbance | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | t (1,37) = 3.9, p < 0.001 |

| Use of Sleep Medication | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | t (1,38) = 3.8, p = 0.001 |

| Daytime Dysfunction | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | t (1,38) = 4.0, p < 0.001 |

| Global Score | 10.2 ± 3.7 | 2.9 ± 1.5 | t (1,35) = 8.6, p < 0.001 |

| ESS | 6.8 ± 4.9 | 5.7 ± 3.5 | t (1,39) = 1.1, p = 0.27 |

| M-E Scale (M, sd) | 32.6 ± 9.8 | 40.0 ± 7.7 | t (1,39) = 2.7, p = 0.009 |

Note. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, PSS = Perceived Stress Scale, QLESQ = Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, PSQ = Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire, ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale, M-E Scale = Morningness-Eveningness Scale.

Although there were no differences between groups on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, suggesting no significant excessive daytime sleepiness, the sleep of night eaters was impaired as evidenced by the consistently elevated scores in comparison to controls on the Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ) (Table 4). Night Eaters had significantly lower scores on the Morningness-Eveningness (ME) scale, indicating that they considered themselves to function better in the latter part of the day than the controls. All PSQ and ME analyses remained significantly different after controlling for experiment-wise error.

3.4 Lifetime Psychiatric Histories

Psychiatric histories were assessed with the SCID; only full threshold diagnoses are described. Night eaters (73.7%) were significantly more likely than controls (18.2%) to meet lifetime criteria for Axis I disorders (χ2 (1) = 12.7, p= 0.001). Unipolar mood disorders and anxiety disorders were the most common lifetime diagnosis among the night eaters (52.6% and 47.4%, respectively). Night eaters (52.6%) were significantly more likely to meet lifetime full criteria for a unipolar mood disorder compared to controls (9.1%) (χ2 (1) = 9.3, p = 0.002); in all cases of unipolar mood disorder, persons met criteria for major depressive disorder. Persons with NES (47.4%) were also significantly more likely to meet criteria for anxiety disorders than were controls (9.1%) (χ2 (1) = 7.6, p = 0.006).

Twenty-six percent of night eaters, compared to none of the controls, met lifetime criteria for substance abuse or dependence (Fischer’s Exact Test p = 0.02). There were no differences between groups for any other class of disorder; of note, persons with lifetime histories of bipolar disorder and psychotic spectrum disorders or current substance abuse or dependence were excluded from the study.

4.0 Discussion

This is the first weight controlled study to characterize fully the circadian distribution of food intake and the psychosocial correlates of NES among non-obese adults. These findings show that NES is associated with an abnormal circadian pattern of food intake, disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, mood and sleep disturbance, elevated perceived stress, decreased quality of life, and greater likelihood of Axis I psychopathology. They support the clinical significance of this diagnosis, independent of the presence of obesity.

Several of this study’s findings are worthy of further discussion, including its replication of previous research showing increased Axis I psychopathology among night eaters. Similar to a recent study by de Zwaan and colleagues (2006), NES was associated with increased rates of unipolar mood disorders and anxiety disorders. Previous research has found increased rates of NES among persons diagnosed with substance use disorders (Lundgren et al., 2006). This was the first study to find increased rates of substance use disorders among persons with a primary complaint of night eating syndrome, suggesting the co-occurrence of these disorders is bi-directional.

Although the rates of co-morbid mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders are high among this NES group, the abnormal eating pattern exhibited by the NES group cannot be accounted for by these co-morbidities. Specifically, there were no differences in the degree of evening hyperphagia, nocturnal awakenings, or nocturnal ingestions of food for night eaters with and without lifetime unipolar mood disorders, anxiety, disorder, or substance use disorders. Similarly, when controlling for BDI scores, most of the analyses between groups remained significant, including the global scores of the PSQ and EDE, EI Cognitive Restraint, Hunger, and Disinhibition, as well as the percentage of evening hyperphagia, frequency of nocturnal awakenings, and frequency of nocturnal ingestions of food (data available upon request).

As would be expected, the delay in the circadian pattern of eating among night eaters was highlighted with the cumulative food intake curves and the survival analysis. As the diagnostic criterion we used for evening hyperphagia was at least 25% of food consumed after the evening meal, we used time to consumption of 75% of intake to compare the groups. The four-hour delay highlights the extent of the circadian differences between the groups in respect to eating, further suggesting that NES is clinically significant among the non-obese.

The nearly 400 calorie difference in total daily food intake between night eaters and controls (Figure 1) raises additional questions, such as the potential role of compensatory behaviors in NES and for weight gain over time. It is apparent, with 50% of total daily intake consumed after the evening meal, that these non-obese night eaters must be restricting food intake during the day. While part of this may be due to lack of hunger upon awakening in the morning, many did not eat anything until the afternoon, and some did not eat until the evening meal. Longitudinal research is necessary to determine if NES leads to weight gain over longer periods of time and whether compensatory behaviors, such as excessive exercise and caloric restriction (successful or unsuccessful), accounts for weight maintenance among those who do not gain weight over time.

NES among non-obese persons appears to share commonalities with the traditional eating disorders, such as increased rates of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Not all non-obese night eaters, however, experience these co-morbid disorders; future studies should assess co-morbid Axis II disorders as well.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and the possibility that persons responding to recruitment advertisements may have higher levels of psychopathology than persons with NES in the community who did not respond. Despite the small sample size, most comparisons were statistically significantly different, even upon adjustment with the Holm-modified Bonferroni.

In conclusion, these results are the first to describe the degree and breadth of negative psychosocial correlates of NES among non-obese persons in comparison to a weight matched control group. These findings complement the Birketvedt et al. (1999) and Marshall et al. (2004) reports showing that non-obese night eaters are not clinically different from obese night eaters. The current findings, however, make clear that nighttime eating behavior among non-obese persons is not benign, even though obesity does not constitute a problem. To the contrary, the current findings show that regardless of BMI, NES is associated with pathological eating attitudes, mood and sleep disturbance, and co-morbid psychopathology.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Reneé Moore, Ph.D. of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Weight and Eating Disorders and the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Jesse Chittams, M.S. of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics for their assistance with the data analyses. Thanks also go to Lisa Basel-Brown, M.S., R.D. of the University of Pennsylvania’s Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC) for analysis of the food records.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK056735 to AJS and M01-RR00040 to the CTRC. KCA was supported by the NIH grant K12 HD043459.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

In this paper, non-obese refers to persons with a BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, as it would be a misnomer to refer to people with a BMI in this range as “normal” or “average” weight given the current prevalence of overweight and obesity in the U.S.

References

- Adami GF, Campostano A, Marinari GM, Ravera G, Scopinaro N. Night eating in obesity: a descriptive study. Nutrition. 2002;18:587–589. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(02)00761-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison KC, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Stunkard AJ. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome: a comparative study of disordered eating. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(6):1107–1115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O’Reardon JP, Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ. The night eating questionnaire (NEQ): Psychometric properties of a screening tool for the diagnosis of night eating syndrome. Eating Behaviors. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.03.007. (In press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using the SAS System. A Practical Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GS, Stunkard AJ, Sorensen TIA, Pedersen L, Heitman BL. Night eating and weight change in middle-aged men and women. Interntional Journal of Obesity. 2004;28:1138–1143. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. The Beck Depression Inventory II. San Antonio: Harcort Brace; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Birketvedt G, Florholmen J, Sundsfjord J, Osterud B, Dinges D, Bilker W, Stunkard AJ. Behavioral and neuroendocrine characteristics of the night-eating syndrome. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:657–663. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceru-Björk C, Andersson I, Rössner S. Night Eating and nocturnal eating—two different or similar syndromes among obese patients? International Journal of Obesity. 2001;25:365–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR, Snell EJ. Analysis of Survival Data. London: Chapman & Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- de Zwaan M, Roerig DB, Crosby RD, Karaz S, Mitchell JE. Nighttime eating: a descriptive study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:224–232. doi: 10.1002/eat.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q): A new measure. Psychopharmachology Bulletin. 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel S. Item response theory of the night eating syndrome. Talk presented at the Annual Meeting of the Eating Disorder Research Society; Toronto, Canada. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. 12th Ed. New York: Guilford; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, Benjamin L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV- Patients edition (with psychotic screen, version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J. Interaction effects in factorial analysis of variance. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1990. pp. 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Johns MW. Sleepiness in different situations measured by the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1994;17:703–710. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.8.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Crow S, O’Reardon JP, Berg KC, Galbraith J, Martino NS, Stunkard AJ. Prevalence of the night eating syndrome in a psychiatric population. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:156–158. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall HM, Allison KC, O’Reardon JP, Birketvedt G, Stunkard AJ. Night eating syndrome among nonobese persons. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:217–222. doi: 10.1002/eat.10241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand CSW, Macgregor MD, Stunkard AJ. The night eating syndrome in the general population and among post-operative obesity surgery patients. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22:65–69. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199707)22:1<65::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CS, Reilly C, Midkiff K. Evaluation of three circadian rhythm questionnaires with suggestions for an improved measure of morningness. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1989;74:728–737. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.74.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, Thompson D, Affenito S, Kraemer HC. Night Eating: Prevalence and Demographic Correlates. Obesity Research. 2006;14:139–147. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ, Grace WJ, Wolff HG. The night-eating syndrome: A pattern of food intake among certain obese patients. American Journal of Medicine. 1955;19:78–86. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(55)90276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]