Abstract

The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) from Torpedo electric organ is a pentamer of homologous subunits. This receptor is generally thought to carry two high affinity sites for agonists under equilibrium conditions. Here we demonstrate directly that each Torpedo nAChR carries at least four binding sites for the potent neuronal nAChR agonist, epibatidine, i.e., twice as many sites as for α-bungarotoxin. Using radiolabelled ligand binding techniques, we show that the binding of [3H]-(±)-epibatidine is heterogeneous and is characterized by two classes of binding sites with equilibrium dissociation constants of about 15 nM and 1 µM. These classes of sites exist in approximately equal numbers and all [3H]-(±)-epibatidine binding is competitively displaced by acetylcholine, suberyldicholine and d-tubocurarine. These results provide further evidence for the complexity of agonist binding to the nAChR and underscore the difficulties in determining simple relationships between site occupancy and functional responses.

Keywords: acetylcholine, nicotinic, epibatidine, α-bungarotoxin, suberyldicholine

Introduction

Detailed characterization of the Torpedo nAChR, the prototype of the ‘cys-loop’ family of ligand-gated ion channels [see 1], has been facilitated by its abundance in the electric organ and its defined subunit structure (α2βγδ). The binding of agonists and competitive antagonists to the nAChR has been extensively scrutinized. It is now generally agreed that, under equilibrium conditions, each receptor carries two high affinity binding sites and that these sites are formed by discrete ‘loops’ of amino acids that lie at the α–γ and α–δ subunit interfaces [2–4]. The location of these sites has been corroborated by elucidation of the crystal structures of related acetylcholine binding proteins (AChBPs) [e.g. 5–7]. There is, however, a body of information to indicate that the binding sites may be more complex than is readily apparent from static structures. In early studies, for example, the binding of bisquaternary amines to solubilized receptors suggested multiple subsites for ligand interaction [8]. Additionally, the ability of various monoclonal antibodies to differentially block the binding of different classes of cholinergic ligands suggested the presence of multiple, possibly three, distinct subsites within each high affinity binding domain [9]. Later, studies of the kinetics of association and dissociation of radiolabelled ACh and the bisquaternary agonist, suberyldicholine (SbCh), again suggested that each high affinity site may be made up of two subsites [10,11].

In addition to the complexity of subsites within the high affinity site, we have previously presented evidence for distinct agonist binding sites on the nAChR. We identified low affinity agonist-specific sites, which displayed properties that were consistent with the involvement of these sites in channel activation [12–14]. Supporting evidence for multiple binding sites has come from studies of α-dendrotoxin binding [15], photoaffinity labeling [16] and from flux studies of pre-formed receptor-ligand complexes [17]. In this report, we have characterized the binding of an agonist, epibatidine [18], to the Torpedo nAChR and directly demonstrate the presence of four agonist binding sites under equilibrium conditions.

Materials and methods

Unlabelled Ligands

(±)-Epibatidine HCl was obtained from Tocris (Ballwin, MO), Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd (Oakville, Ontario) or RBI (Natick, MA). (+)-Epibatidine L-tartrate, carbamylcholine chloride, acetylcholine chloride, diethyl-p-nitrophenylphosphate (DNPP), chlorpromazine hydrochloride and d-tubocurarine (d-TC) were also from Sigma. Suberyldicholine dichloride was from Aldrich and methyltriphenylphosphoium bromide (MTPPBr) from Pfaltz and Bauer, Inc. β-Erythroidine was a generous gift from Dr. Virgil Boekelheide (University of Oregon, OR).

Radiolabelled Ligands

[125I]-αBTx was from DuPont Canada or DuPont USA and was calibrated as previously described [19]. [3H]-ACh (specific activity = 46.9 mCi/mmol) was from DuPont-NEN Canada and [3H]-SbCh (74 mCi/mmol) was synthesized and its specific activity determined as described [10]. [3H]-(±)-epibatidine (two batches of 33.8 Ci/mmol and 66.6 Ci/mmol) was obtained from New England Nuclear Life Sciences (Boston, MA) and was isotopically diluted to make stock solutions of 1 mM with a specific activity of 48 - 50 mCi/mmol. The concentration of labeled (±)-epibatidine was determined by its absorbance at 268 nm (EmM = 0.384) and at 217 nm (EmM = 0.96). The results presented here rely on the accurate calibration of the [3H]-(±)-epibatidine stock solutions. Extinction coefficients were, therefore, determined independently in our two laboratories using unlabelled (±)-epibatidine of different batches from three different sources. The purity of tritiated ligands was examined by paper (Whatman #1) chromatography in 70% propanol. Staining for amines using the Dragendorff reagent [20] and counting of strips for radioactivity identified one location, demonstrating isotopic purity.

Preparation of nAChR-Enriched Membrane Fragments

Membranes were prepared from frozen electric organ of Torpedo californica (Biomarine, San Pedro, CA or Aquatic Consultants, San Pedro, CA) as described previously [21] and stored frozen at −85°C. Prior to use, the membranes were alkali-extracted to remove peripheral proteins [22, 23] and were finally resuspended in Ca2+ free Torpedo Ringers (20 mM Hepes, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.02% NaN3, pH 7.4). Protein concentrations were measured by the BioRad assay and the concentration of [125I]-αBTx sites was measured by DEAE-disc assay [24]. Specific activities of the Torpedo receptor preparations were in the range of 1–3 nmol of [125I]-αBTx sites per milligram of protein.

Equilibrium Radiolabelled Ligand Binding Measurements

Prior to binding experiments, acetylcholinesterase activity was inhibited by incubating concentrated membrane preparations (approximately 10 µM in α-BTx binding sites) with 0.5% volume of a stock solution of 0.3 M DNPP in isopropanol for 3 minutes at room temperature [10]. Following treatment, the membranes were diluted approximately 50-fold in Torpedo Ringers containing 4 mM CaCl2 and stored on ice until use. The equilibrium binding of radiolabelled ligands was routinely measured by centrifugation assays [25]. In saturation binding experiments, the radioligand was incubated with DNPP-treated Torpedo membranes for 30 min at room temperature followed by centrifugation for 20 minutes in a microcentrifuge at 12000g and 4°C. Total and free radioligand concentrations were estimated from counting duplicate aliquots (75 µl each) of the original sample and of the supernatant after centrifugation. Nonspecific binding was estimated from the results of parallel samples in which a large excess of unlabelled ligand was included in the incubation mixture. The displacement of radioligands by unlabelled ligands was measured in competition experiments using a similar centrifugation assay.

In experiments in which higher concentrations of receptor were used, binding was measured by equilibrium dialysis using microdialysis chambers (Chemical Rubber Company) and 50 K molecular weight cutoff dialysis tubing (SpectraPor). The DNPP-treated membranes (0.4 ml per sample) were dialysed against 0.4 ml radiolabelled ligand for 6 hours with rocking at 4° C [10]. Total and free radioligand concentrations were estimated by taking duplicate 50 µl samples from each compartment and counting for radioactivity. Nonspecific binding was measured in the presence of a large excess of unlabelled ligand.

Data analysis

All data were analysed using Prism 3 software (GraphPad Inc., San Diego). Saturation binding data were analysed using either a one-site or two-site hyperbolic function:

where [B] is the concentration of bound radioligand, [F] is the concentration of free radioligand, Bmax1 and Bmax2 are the concentrations of the two classes of binding sites, Kd1 and Kd2 are their corresponding equilibrium dissociation experiments and NSP is non-specific binding. Competition binding data were fit by either a competition model with variable Hill coefficient (nH):

or a two component model:

where [B] is bound radioligand, Bmin and Bmax are the minimum and maximum amount of bound radioligand, [X] is the total concentration of competing ligand, FH is the fraction of high affinity sites and IC50(1) and IC50(2) are the IC50 values for the high and low affinity components respectively.

Results

Epibatidine binds to four sites per receptor molecule

Initial experiments to characterize the equilibrium binding of [3H]-(±)-epibatidine to the Torpedo nAChR were carried out using centrifugation assays and relatively low receptor concentrations (0.1 – 0.5 µM in [125I]-αBTx sites). The binding of [3H]-(±)-epibatidine was obviously heterogeneous and non-linear regression curve fitting indicated the presence of two populations of sites that existed in approximately equal proportions (Figure 1A). A Scatchard plot of these data (Figure 1B) more clearly illustrates this binding site heterogeneity. Averaged data gave affinity estimates of 15.2 ± 3.1 nM and 0.42 ± 0.05 µM (mean ± s.e.m., n = 6) for the two classes of sites. The most important finding is that the total number of binding sites exceeds those for α-BTx by a factor of 2. Since α-BTx is known to bind to two sites per receptor, these results indicate that there are four measurable sites for [3H]-(±)-epibatidine on each nAChR. In order to eliminate complications that could possibly have arisen from inaccurate determinations of the toxin specific activity, most experiments included parallel studies of [3H]-ACh and [3H]-SbCh binding and the results demonstrated that, as expected, these ligands bind to an equivalent number of sites as [125I]-α-BTx. Thus the presence of four measurable binding sites for epibatidine has been independently verified using four radiolabelled ligands whose specific activities have been accurately determined [10, also see Methods section].

Fig. 1.

The equilibrium binding of [3H]-(±)-epibatidine to Torpedo membranes (0.5 µM in α-BTx binding sites) was measured by a centrifugation assay. (A) The dashed line represents the best fit for binding to a single population of sites with Bmax = 0.88 µM and Kd = 34 nM. The solid line shows a better fit to a two component model with Bmax1 = 0.56 µM, Kd1 = 13.5 nM, Bmax2 = 0.38 µM and Kd2 = 0.29 µM. (B) A Scatchard transformation of the data in (A) with the solid line calculated using the parameters obtained from the two component model in (A).

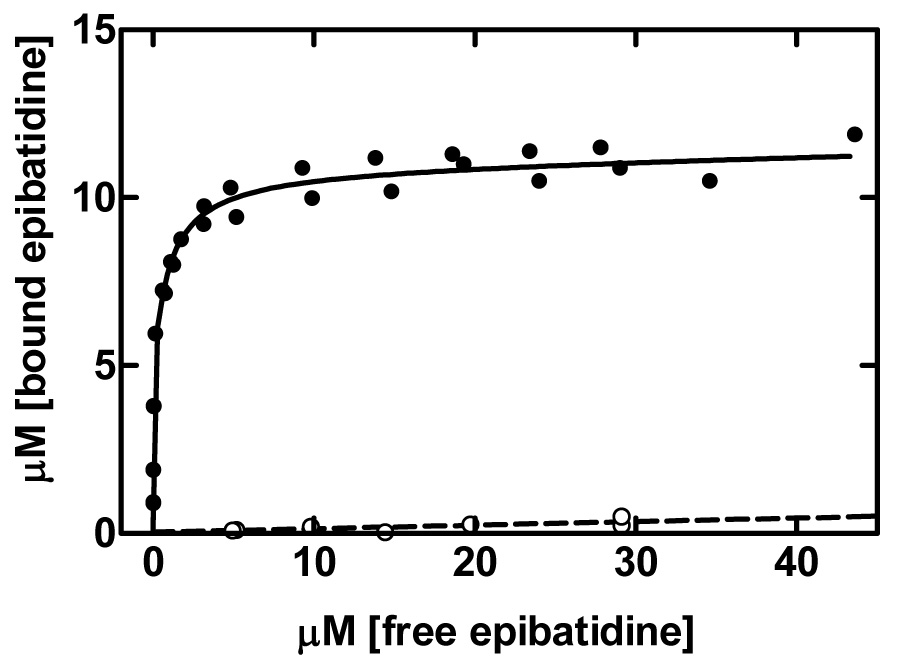

For better determination of the binding parameters for the lower affinity sites, we further performed equilibrium binding experiments using an equilibrium dialysis method and higher concentration of receptors. Equilibrium dialysis reduces the complications that arise from the necessity of separating bound and free ligand in centrifugation or filtration assays [26]. Figure 2 shows representative data using a nAChR concentration of 5 µM (in α-BTx binding sites). The maximum concentration of bound [3H]-(±)-epibatidine was again twice that of [125I]-α-BTx binding, confirming a stoichiometry of four sites per receptor. Dissociation constants obtained from equilibrium dialysis studies were 12.4 ± 2.5 nM and 1.1 ± 0.4 µM (n = 5).

Fig. 2.

The binding of [3H]-(±)-epibatidine to Torpedo membranes (5 µM in α-BTx sites) was measured by equilibrium dialysis. [3H]-(±)-epibatidine binds to approximately twice as many sites as α-BTx and fitting by a two state model gave Bmax1 = 4.96 µM, Kd1 = 10.4 nM, Bmax2 = 5.95 µM, Kd2 = 0.98 µM. The curve for total binding (●) includes a non-specific binding (○) component of 0.0106 µM bound/µM free measured the presence of excess unlabelled ligand. Data are averaged from two independent experiments and are representative of five similar assays carried out using high concentrations of nAChR (2.5 – 5 µM in α-BTx sites).

These experiments, in a straightforward manner, demonstrate that epibatidine binds to four sites per nAChR molecule with two classes of sites that differ in affinity by approximately 50-fold.

Radioligand displacement studies with cholinergic agonists

To examine the relationship of the measured epibatidine binding sites to the two well characterized high affinity binding sites, we conducted equilibrium competition binding assays with several radiolabeled agonists. Figure 3A shows representative data for the displacement of [3H]-ACh by unlabelled ligands. As expected from previous studies [10], ACh displaced [3H]-ACh in an apparently competitive fashion. Displacement of [3H]-ACh by (±)-epibatidine was also complete but the curves were clearly biphasic giving IC50 values of 148 nM and 8.05 µM with an approximately equal number of sites. As described [27], it is very difficult to convert these IC50 values to KI constants in cases (such as this) where the receptor concentration is high, the binding is complex and the free concentration of unlabelled ligand cannot be determined readily. Overall, however, the estimated IC50 values are in agreement with direct determinations of affinities as shown in Figure 1. Figure 3A also shows data for displacement of [3H]-ACh by (+)-epibatidine. The results suggest that this isomer has lower affinity for both classes of sites than the racemic mixture suggesting that (−)-epibatidine has higher affinity for the Torpedo receptor. Since the major observation of this report is on the number of sites rather than the differential affinities of the binding sites, we have not pursued this issue further. However, the biphasic displacement of [3H]-ACh by both (±)-epibatidine and (+)-epibatidine clearly demonstrates that the two classes of binding sites measured in direct [3H]-(±)-epibatidine binding studies cannot be simply attributed to the racemic nature of the radiolabelled ligand.

Fig. 3.

Displacement of radiolabelled agonist by unlabelled ligands. In each case the receptor concentration was 0.3 µM in α-BTx sites. (A) Displacement of [3H]ACh (1 µM) by ACh (○) was well described by a simple sigmoidal curve giving IC50 = 0.60 µM and nH = 1 whereas the effects of (±)epibatidine (■) was biphasic giving IC50(1) = 0.148 µM, IC50(2) = 8.05 µM and FH = 0.528. Corresponding data for (+)-epibatidine (▲) gave IC50(1) = 0.307 µM, IC50(2) = 61.6 µM and FH = 0.56. (B) Displacement of [3H]-(±)-epibatidine (0.5 µM) by ACh (○) was biphasic and curve fitting gave IC50(1) = 0.36 µM, IC50(2) = 11.5 µM and FH = 0.644. In contrast displacement by (±)-epibatidine (■) can be described by a one-component fit with IC50 = 0.47 µM and nH = 1. (C) Displacement of [3H]-SbCh (1 µM) by ACh (○) was best described by a sigmoidal curve with IC50 = 1.39 µM and nH = 0.733. The effects of (±)-epibatidine (■) were described by a similar model with IC50 = 2.34 µM and nH = 0.598.

We next performed competition experiments with radiolabeled epibatidine. (±)-Epibatidine displaced [3H]-(±)-epibatidine in a monophasic manner with an IC50 value of about 0.5 µM and a Hill coefficient not significantly different from 1 (Figure 3B). In contrast, Ach displacement was biphasic with IC50s differing by about 30-fold (0.36 and 11.5 µM in this representative experiment) and with the higher affinity component accounting for about 64% of the total. Thus although (±)-epibatidine binds to twice as many sites as ACh under equilibrium conditions, all radiolabelled epibatidine binding is displaced by ACh. This suggests that there are cooperative interactions amongst the sites.

We have previously proposed that each high affinity site in the nAChR is made up of two subsites that could be bridged by SbCh [10,11]. In order to investigate whether the “extra” binding sites for [3H]-(±)-epibatidine may be one of the subsites, we studied the ability of Ach and (±)-epibatidine to displace [3H]-SbCh from its receptor sites. As shown in Figure 3C, all bound [3H]-SbCh was displaced by ACh and (±)-epibatidine. Analysis using a two-site model did not statistically improve the fits, but using sigmoidal curve fitting, the Hill coefficient in each case was less than one, again suggesting cooperative interactions among sites.

The effects of competitive and non-competitive antagonists

The competitive cholinergic antagonist, d-TC, displaced all [3H]-(±)-epibatidine binding (Figure 4) with an IC50 of 22.1 µM. Again the shallow Hill coefficient suggests heterogeneity but this may be attributable, at least in part, to the known heterogeneity in d-TC binding [28]. Another competitive inhibitor, β-erythroidine, which is essentially half a d-TC molecule that carries only one positive charge, caused partial displacement of [3H]-(±)-epibatidine but only at very high concentrations. The noncompetitive inhibitors, chlorpromazine-HCl and MTPP-Br, had little effect on [3H]-(±)-epibatidine binding. It is thus unlikely that the “extra” sites for (±)- epibatidine are the sites for noncompetitive blockers that are found, at least in part, within the vestibule of the ion channel.

Fig. 4.

The effects of receptor inhibitors on the binding of [3H]-(±)-epibatidine. [3H]-(±)-epibatidine (0.5 µM) was incubated with nAChR enriched membranes (0.3 µM in α-BTx sites) and the effects of d-tubocurarine (●), β-erythroidine (○), chlorpromazine HCl (▼) and MTPP-Br (◇) were measured using a centrifugation assay. Only d-tubocurarine caused significant displacement below 100 µM and the data were best fit by a sigmoidal competition curve with IC50 = 22.1 µM and nH = 0.681.

Discussion

The novelty of this report is that the agonist [3H]-(±)-epibatidine binds to four sites on the Torpedo nAChR i.e., twice as many sites as for α-BTx and ACh. The epibatidine sites are heterogeneous and are characterized by two populations that exist in equal numbers and have affinities of approximately 15 nM and 1.0 µM. We show that this heterogeneity cannot be explained by the racemic nature of the radioligand used. Competitive binding studies have shown that all [3H]-(±)-epibatidine binding is displaced by the agonists, ACh and SbCh and by the competitive antagonist, d-TC. However, displacement curves were either biphasic or displayed low Hill coefficients, suggesting that there are cooperative interactions amongst the sites.

Sine and colleagues [29,30] previously reported heterogeneity of epibatidine binding to the homologous fetal and adult muscle receptors with apparent affinities that are generally consistent with those reported here. In these earlier studies, affinities for epibatidine isomers were measured indirectly by their ability to inhibit the initial rate of [125I]-α-BTx binding and thus no direct determination of the number of epibatidine sites could be made. By studying epibatidine binding to intracellular complexes of subunit pairs (αγ, αδ, αε) and subunit-deficient receptors (α2βγ2, α2βε2,α2βδ2) expressed on the cell surface, convincing evidence was provided to suggest that the higher affinity epibatidine binding was conferred by a site lying at the α−γ (or α−ε) interface and that lower affinity binding could be attributed to a site at the α−δ interface [29]. However, in the case of epibatidine binding to the intracellular dimers or subunit-depleted receptors, the Hill coefficients were less than one, suggesting that there may be heterogeneity of binding sites within each interface. These earlier results may be explained, as suggested [29], by the formation of a mixed population of receptor complexes or by the presence of different receptor conformations. However, based on the above evidence for four epibatidine sites on each native Torpedo receptor, we suggest that there are two epibatidine binding sites associated with each of the α−γ and α−δ interfaces.

Binding sites within the nAChR are sufficiently flexible to accommodate ligands with diverse chemical structures. The specific subset of residues with which different ligands interact may overlap but are not necessary identical, as illustrated in the crystal structures of the Aplysia AChBP complexed with ligands [6, 7]. Further, our kinetic studies [10, 11] suggested that each high affinity binding site is associated with a secondary site lying approximately 15Å away. Although, under equilibrium conditions, these sites were mutually exclusive for ACh, it appeared that the large bis-functional agonist, SbCh could physically bridge the two subsites. The present data, demonstrating the presence of four (±)-epibatidine binding sites are consistent with the possibility that, unlike ACh, epibatidine can simultaneously occupy both of the subsites associated with each high affinity binding domain.

Acknowledgments

We thank David K. Okita (Minnesota), Brian Tancowny (Alberta) and Isabelle Paulsen (Alberta) for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (SMJD) and by NIDA Program Project Grant DA08131 (MAR).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lester HA, Dibas MI, Dahan DS, Leite JF, Dougherty DA. Cys-loop receptors: new twists and turns. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corringer PJ, Le Novere N, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptors at the amino acid level. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000;40:431–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sine SM. The nicotinic receptor ligand binding domain. J. Neurobiol. 2002;53:431–446. doi: 10.1002/neu.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karlin A. Emerging structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrn731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brejc K, van Dijk WJ, Klassen RV, Schuurmans M, van Der Oost J, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2001;411:269–276. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celie PH, Kasheverov IE, Mordvintsev DY, Hogg RC, van Nierop P, van Elk R, van Rossum-Fikkert SE, Zhmak MN, Bertrand D, Tsetlin V, Sixma TK, Smit AB. Crystal structure of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor homolog AChBP in complex with an alpha-conotoxin PnIA variant. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:582–588. doi: 10.1038/nsmb951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen SB, Sulzenbacher G, Huxford T, Marchot P, Taylor P, Bourne Y. Structures of Aplysia AChBP complexes with nicotinic agonists and antagonists reveal distinctive binding interfaces and conformations. EMBO J. 2005;24:3635–3646. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bode J, Moody T, Schimerlik M, Raftery MA. Uses of fluorescent cholinergic analogues to study binding sites for cholinergic ligands in Torpedo californica acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry. 1979;18:1855–1861. doi: 10.1021/bi00577a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watters D, Maelicke A. Organization of ligand binding sites at the acetylcholine receptor: a study with monoclonal antibodies. Biochemistry. 1983;22:1811–1819. doi: 10.1021/bi00277a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn SMJ, Raftery MA. Agonist binding to the Torpedo acetylcholine receptor. 1. Complexities revealed by dissociation kinetics. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3846–3853. doi: 10.1021/bi961503d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn SMJ, Raftery MA. Agonist binding to the Torpedo acetylcholine receptor. 2. Complexities revealed by association kinetics. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3854–3863. doi: 10.1021/bi9615046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunn SMJ, Raftery MA. Activation and desensitization of Torpedo acetylcholine receptor: evidence for separate binding sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1982;79:6757–6761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.22.6757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn SMJ, Raftery MA. Multiple binding sites for agonists on Torpedo californica acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6264–6272. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn SMJ, Raftery MA. Cholinergic binding sites on the pentameric acetylcholine receptor of Torpedo californica. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8608–8615. doi: 10.1021/bi00084a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conti-Tronconi BM, Raftery MA. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor contains multiple binding sites: evidence from binding of alpha-dendrotoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1986;83:6646–6650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tine SJ, Raftery MA. Photoaffinity labeling of Torpedo acetylcholine receptor at multiple sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:7308–7311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn SMJ, Raftery MA. Roles of agonist-binding sites in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;279:358–362. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spande TF, Garraffo HM, Yeh HJ, Pu QL, Pannell LK, Daly JW. A new class of alkaloids from a dendrobatid poison frog: a structure for alkaloid 251F. J. Nat. Prod. 1992;55:707–722. doi: 10.1021/np50084a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchard SG, Quast U, Reed K, Lee T, Schimerlik MI, Vandlen R, Claudio T, Strader CD, Moore H-P, Raftery MA. Interaction of [125I]-alpha-bungarotoxin with acetylcholine receptor from Torpedo californica. Biochemistry. 1977;15:1875–1883. doi: 10.1021/bi00577a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heftmann E. Chromatography. second ed. New York: Reinhold Chemistry Textbook Series; 1967. p. 607. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott J, Blanchard SG, Wu W, Miller J, Strader CD, Hartig P, Moore HP, Racs J, Raftery MA. Purification of Torpedo californica post-synaptic membranes and fractionation of their constituent proteins. Biochem. J. 1980;185:667–677. doi: 10.1042/bj1850667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neubig RR, Krodel EK, Boyd ND, Cohen JB. Acetylcholine and local anesthetic binding to Torpedo nicotinic postsynaptic membranes after removal of nonreceptor peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1979;76:690–694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.2.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott J, Dunn SMJ, Blanchard SG, Raftery MA. Specific binding of perhydrohistrionicotoxin to Torpedo acetylcholine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1979;76:2576–2579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.6.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt J, Raftery MA. A simple assay for the study of solubilized acetylcholine receptors. Anal. Biochem. 1973;52:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunn SMJ, Blanchard SG, Raftery MA. Kinetics of carbamylcholine binding to membrane-bound acetylcholine receptor monitored by fluorescence changes of a covalently bound probe. Biochemistry. 1980;19:5645–5652. doi: 10.1021/bi00565a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies M, Dunn SMJ. Characterization of receptors by radiolabeled ligand binding techniques. In: Boulton AA, Baker GB GB, Bateson AN, editors. Neuromethods. Volume 34. New Jersey: Vitro Neurochemical Techniques, Humana Press; 1999. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motulsky HJ, Christopoulos A. A practical guide to curve fitting. San Diego, CA: GraphPad Software Inc.; 2003. Fitting models to biological data using linear and nonlinear regression. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neubig RR, Cohen JB. Equilibrium binding of [3H]tubocurarine and [3H]acetylcholine by Torpedo postsynaptic membranes: stoichiometry and ligand interactions. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5464–5475. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prince RJ, Sine SM. Epibatidine binds with unique site and state selectivity to muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7843–7849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennington RA, Gao F, Sine SM, Prince RJ. Structural basis for epibatidine selectivity at desensitized nicotinic receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;67:123–131. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.003665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]