Abstract

Bisubstrate analog inhibitors in which a nicotinamide mimic is attached to a series of structurally diversified guanidines (arginine mimics) were synthesized and evaluated for inhibition of cholera toxin. The mechanism-based bisubstrate inhibitors were up to 1400-fold more potent than the natural substrate NAD+ and 400-fold more potent than the artificial substrate diethylamino (benzylidine-amino) guanidine (DEABAG) in an assay toward an intrinsically active mutant of wild-type cholera toxin.

Cholera is a devastating diarrheal disease that is caused by infection of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It is responsible for thousands of deaths each year.1 People are usually infected by drinking contaminated water and they often suffer from profuse watery diarrhea.2–4 The massive intestinal fluid loss is primarily due to the release of the heterohexameric cholera toxin (CT). CT is composed of a catalytically active A subunit and five identical B subunits responsible for receptor binding.5 CT binds to the exterior of the human epithelial cell by its B subunits and gets internalized into the cell.6 It is first transported retrograde from the plasma membrane to the trans-Golgi6,7 and then to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)6,8,9. In the ER, the A subunit separates from the B subunits and the A1 chain is reduced,10,11 freed from the carrier holotoxin, and gets translocated to the cytosol,12,13 where the active A1 domain gains access to its substrate, including the α subunit of the stimulatory G protein (Gsα). A1 modifies Gsα through an NAD-dependent ADP-ribosylation reaction.14 ADP-ribosylation of Arg201 of Gsα locks the G protein in its GTP-bound state and persistently stimulates adenylyl cyclase. The consequent dramatic production of cAMP activates the Cl− ion channels.7,15 The imbalance of ions causes an efflux of cellular water to the gut, which eventually produces host dehydration and diarrhea.

Oral rehydration therapy is the most important treatment for cholera,16 however, its applications are limited by its reliance on large amounts of clean water in areas where outbreaks occur. On the other hand, substantial efforts have been made to develop vaccines, but they are only effective for a short period of time;17 there has been no known marketed drug that directly targets cholera toxin. Several promising strategies have been revealed for the design of therapeutic agents for CT. These include blocking the enzyme active site in the A subunit,18,19 disrupting the assembly of the AB5 holotoxin,20 intercepting the receptor binding of the B pentamer,21–24 and inhibiting adenylate cyclase.25

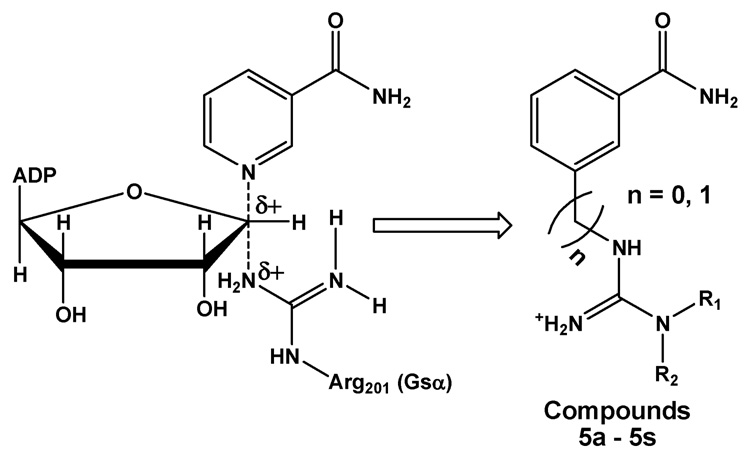

Since very few studies have focused on the inhibition of the enzymatically active cholera toxin A subunit (CTA), our goal was to design inhibitors to block the CT active site that resides in A1. There have been disagreements regarding the reaction mechanism of ADP-ribosylation by CTA.26–28 However, the latest study on kinetic isotope effects suggested that the reaction followed a dissociative concerted mechanism (i.e. SN2).28 Lacking the crystal structure of substrate-bound CT when we initiated our work, we designed a series of bisubstrate analogs as potential inhibitors, which incorporate key moieties from both the ADP-ribose donor (NAD+) and the ADP-ribose acceptor (Arg201 of Gsα). Our design of bisubstrate analogs is shown below (Figure 1). In this work, we selected benzamide as the analog for the nicotinamide moiety of NAD+, which is subsequently linked to a substituted guanidine, mimicking Arg201 of Gsα. The substitutions on the guanidine moiety allow one to test diverse molecular moieties to improve inhibitor potency. Our design is based on the assumption that both NAD+ and guanidine have a well defined binding site and that linking them together could be an effective strategy to enhance inhibitor affinity.

Figure 1.

Design of bisubstrate analog targeting CTA. This analog prototype includes three features: 1. benzamide would mimic the nicotinamide portion of the substrate NAD+; 2. incorporation of substituted arginine (R1 and R2), mimicking Arg201 moiety of Gsα as ADP-ribosyl receptor; 3. insertion of the methylene group as a spacer (in parentheses).

The guanidine library was synthesized on the solid phase using Rink amide MBHA resin and the synthesis is summarized in Scheme 1, taking advantage of the solid phase synthetic method developed in our laboratory that employed an arylsulfonylthiourea-assisted guanidine synthesis.29 In a typical synthesis shown in reaction sequence 1, 3-(N-Fmoc-aminomethyl) benzoic acid was coupled to the solid support under standard PyBOP/DIPEA conditions in DMA. After the removal of Fmoc, resin-supported 1 was suspended in methylene chloride and reacted with pentafluorophenyl chlorothioformate. The resin-bound thiocarbamate 2 reacted with 2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyl-dihydrobenzofuran-5-sulfonamide (Pbf-NH2) in DMSO with the presence of potassium tert-butoxide and formed thiourea 3. Subsequent reaction with an amine nucleophile and EDC in DMF gave the target molecule. Following reaction sequence 2, target compounds can also be prepared by the reaction of resin-bound 1 under either EDC or Mukaiyama reagent conditions with the corresponding thiourea precursors that are prepared in solution phase. Guanidine compounds without an alkyl linker were synthesized using the same method, with the only difference being the use of 3-(N-Fmoc-amino) benzoic acid instead. The product was cleaved off the solid support by a cocktail mixture (TFA/TIS/H2O v/v 94:3:3), and purified using reversed-phase HPLC in the presence of 0.1% TFA. The structural interpretation of the desired compounds was carried out by 1H NMR and mass spectrometry.

Scheme 1.

Solid phase synthesis of CT inhibitors. For analogs without alkyl linker, 3-(N-Fmoc-amino) benzoic acid was used in step b instead. Both sequence 1 and sequence 2 are applicable. Reagents: a) 20% piperidine/DMA; b) PyBOP, DIPEA, DMA; c) EDC or Mukaiyama reagent, DMF; d) 94:3:3 TFA:H2O:TIS; e) pentafluorophenyl chlorothioformate, DIPEA, CH2Cl2; f) PbfNH2, potassium tert-butoxide, DMSO.

The target compound library was examined in an enzymatic assay toward inhibiting CTY30S (Table 1), an intrinsically active CT mutant which has displayed similar activity as wild-type CT.30 An artificial substrate diethylamino(benzylidine-amino)guanidine (DEABAG) was used as an alternative ADP-ribose acceptor.27 The reaction progress was monitored by analytical HPLC because all important components in the assay are chromogenic. Calibrated by the UV absorbance of the internal standard theophylline (Figure 2), the inhibitory activity of our compounds can be evaluated by the progress of ADP-ribosylation as compared to the control. The library compounds were screened at 1.0 mM concentration in 200 mM PBS buffer at 37°C and pH 7, and the screening results are described in Table 1. Kinetic studies were conducted for those compounds that demonstrated a percentage inhibition of over 90%. The Km values of NAD+ and DEABAG were determined to be 14 and 4.0 mM respectively, which are in good agreement with previous reports;31–34 while the IC50 values of compound 5a, 5j, 5l, 5m, and 5q varied in a range between 40 and 270 µM (Table 1), with 5q35 being the most potent. Its estimated Ki is ~10 µM and this result is better than the best CT inhibitors reported previously.18

Table 1.

Summary of screening results of all bisubstrate analogsa and IC50 and estimated Ki for selected compounds.

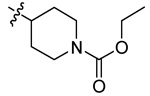

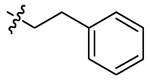

| Structure | Compounds | R1 | R2 | nb | % Inhibitionc | IC50 (µM) | Est. Ki36,d (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

5ae | iPr | iPr | 1 | 94 | 115±18 | 30±5 |

| 5b | Et | Et | 1 | 24 | - | - | |

| 5c | tBu | H | 1 | 39 | >2000 | >500 | |

| 5d |  |

H | 0 | 22 | - | - | |

| 5ee | Ph | H | 1 | 57 | - | - | |

| 5f |  |

H | 1 | 68 | - | - | |

| 5g |  |

H | 1 | 76 | - | - | |

| 5h |  |

H | 1 | 34 | - | - | |

| 5i |  |

H | 1 | 57 | - | - | |

| 5j |  |

H | 1 | 93 | 272±16 | 71±4 | |

| 5k |  |

H | 1 | 97f | - | - | |

| 5le |  |

H | 1 | 96 | 49±6 | 13±2 | |

| 5m | Bn | H | 1 | 93 | 192±7 | 50±2 | |

| 5n | iPr | iPr | 0 | 15 | 350 | 90 | |

| 5o | tBu | H | 0 | 77 | - | - | |

| 5p | Ph | H | 0 | 12 | >2000 | >500 | |

| 5qe |  |

H | 1 | 98 | 31±12 | 8±3 | |

| 5r | Bn | H | 0 | 10 | - | - | |

| 5s |  |

H | 0 | 58 | - | - |

All the synthetic compounds were evaluated as opposed to a random non-inhibitor, galactose, which serves as negative control.

n respresents the number of methylene group as a spacer (also see Figure 1).

The screening was performed at 1 mM in PBS buffer; only selected compounds were studied for IC50 measurement.

The Ki values are estimated from the equation: Ki = IC50 / ( 1 + [S] / Km).36 The IC50 are those at 40 mM NAD+. Km = 14 mM was used in the calculation.

These compounds have already been examined in dynamic light scattering (DLS) studies.

IC50 of this compound was not studied due to insufficient amount of materials.

Figure 2.

A typical chromatogram for an HPLC-based assay of CT. The one in blue is a control run; the one in red is a run with 0.33 mM of 5q. Each peak has been labeled. The two peaks overlapped in the product area have both been verified by mass spectrometry and 1H NMR to be the reaction product.37 As a result, they were both monitored.

On the basis of these results, bisubstrate analog 5q is 1400-fold more potent than natural substrate NAD+ and 400-fold more potent than DEABAG toward CT. Data analyses indicate that hydrophobic functionalities are preferred as R group. However, when we introduced some other hydrophobic groups, such as biphenyl and 1-naphthyl into our analog, no affinity gain was obtained (data not shown). We did observe that analogs with a one-carbon alkyl linker inserted between benzamide and guanidine are consistently more potent in their inhibitory activities than those who share the same R yet without any spacer. It is worth mentioning that dynamic light scattering studies (DLS) have been carried out for some of the inhibitors with high potency to check for potential compound aggregation caused non-specific inhibition.38 The DLS results indicated that the polydispersity of CT control was around 10.5% and the intensity of the CT peak represented 83% of all solution species. The DLS results for the assay mixture of 5q, CT (at 70 nM), and all the other components showed a polydispersity of 12% and a percent intensity of 92% for CT. To verify the solubility of 5q, its 2-bromo and 3-bromo isomers were also prepared. DLS measurements of solutions of CT with these isomers showed low polydispersity and high percentage intensity too (data not shown). This suggested that these mixtures are free of inhibitor aggregation, ruling out the possibility of nonspecific inhibition in kinetic assays with compound 5q.38 As a comparison, DLS of assay mixtures with compound 5a showed an additional peak and the intensity of the CT peak dropped dramatically to 12.5% of all species. The new particle was calculated to be 2.2 µm in diameter, indicative of the existence of compound induced aggregation.

In summary, we have designed, synthesized, and evaluated a series of bisubstrate analog inhibitors toward CT. Our results demonstrated that the best compound 5q is 1400-fold more potent than natural substrate NAD+. With the recently published crystal structure of a quaternary CTA1-NAD+: ARF6-GTP complex, it could shed new light on designing optimized bisubstrate analog inhibitors with improved potency.

Acknowledgement

I acknowledge the NIH for financial support (AI34501). I thank Profs. Erkang Fan, Christophe Verlinde, and Wim Hol for their stimulating discussions. I thank Dr. Claire O’Neal for providing the CTY30S mutant. I also thank Drs. Zhongsheng Zhang and Jason Pickens for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological record. 2006;81:297.

- 2.De SN. Nature. 1959;183:1533. doi: 10.1038/1831533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutta NK, Panse MV, Kulkarni DR. J. Bacteriol. 1959;78:594. doi: 10.1128/jb.78.4.594-595.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein RA, Norris HT, Dutta NK. J. Infect. Dis. 1964;114:203. doi: 10.1093/infdis/114.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang R-G, Scott DL, Westbrook ML, Nance S, Spangler BD, Shipley GG, Westbrook EM. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;251:563. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lencer WI. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 1994;293:491. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn RA, Fu H, Roy CR. Trends in Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:308. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majoul IV, Bastiaens PI, Soling HD. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:777. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lencer WI, Constable C, Moe S, Jobling MG, Webb HM, Ruston S, Madara JL, Hirst TR, Holmes RK. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:951. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.4.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai B, Rodighiero C, Lencer WI, Rapoport TA. Cell. 2001;104:937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bastiaens PI, Majoul IV, Verveer PJ, Soling HD, Jovin TM. EMBO J. 1996;15:4246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitz A, Herrgen H, Winkeler A, Herzog V. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148 doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teter K, Holmes RK, Schmitz A, Herrgen H, Winkeler A, Herzog V. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:6172. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6172-6179.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai B, Rapoport TA. J. Cell Biol. 2002;159:207. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salmond RJ, Luross JA, Williams NA. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2002 October 1;:1. doi: 10.1017/S1462399402005057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pulungsih SP, Punjabi NH, Rafli K, Rifajati A, Kumala S, Simanjuntak CH, Lesmana M, Subekti D, Sutoto FO. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2006;24:107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological record. 2004;79:281.

- 18.Zhou GC, Parikh SL, Tyler PC, Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Zubkova OV, Benjes PA, Schramm VL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5690. doi: 10.1021/ja038159+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parikh SL, Schramm VL. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1204. doi: 10.1021/bi035907z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovey B, Verlinde CLMJ, Merritt EA, Hol WGJ. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:1169. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan E, Zhang Z, Minke WE, Hou Z, Verlinde CLMJ, Hol WGJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2663. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z, Merritt EA, Ahn M, Roach C, Hou Z, Verlinde CLMJ, Hol WGJ, Fan E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12991. doi: 10.1021/ja027584k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan E, Merritt EA, Verlinde CLMJ, Hol WGJ. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:680. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pukin AV, Branderhorst HM, Sisu C, Weijers CAGM, Gilbert M, Liskamp RMJ, Visser GM, Rol HZ, Pieters J. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zenser TV. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1976;152:126. doi: 10.3181/00379727-152-39342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oppenheimer NJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:4907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soman G, Narayanan J, Martin BL, Graves DJ. Biochemistry. 1986;25:4113. doi: 10.1021/bi00362a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rising KA, Schramm VL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Zhang G, Zhang Z, Fan E. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:1611. doi: 10.1021/jo026807m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Neal CJ, Amaya EI, Jobling MG, Holmes RK, Hol WGJ. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3772. doi: 10.1021/bi0360152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larew JS, Peterson JE, Graves DJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galloway TS, Van Heyningen S. Biochemistry. 1987;244:225. doi: 10.1042/bj2440225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss J, Manganiello VC, Vaughan M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1976;73:4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.12.4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mekalanos JJ, Collier RJ, Romig WR. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:5849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.N-(4-bromobenzyl)-N'-(3-aminocarbonylbenzyl)guanidine (18). From 0.078 mmole of resin-supported A, 18 was obtained in 82% yield as the TFA salt (30 mg). MS:361.0 and 363.0 (M+H)+. 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 4.46 (2H, s, CH2), 4.55 (2H, s, CH2), 7.31 (2H, d), 7.62 (4H, m), 7.95 (2H, m).

- 36.Segel IH. Enzyme kinetics: behavior and analysis of rapid equilibrium and steady state enzyme systems. New York: Wiley; 1975. p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Both product peaks were collected separately, and N-(ADP-ribose)-N'-diethylamino(benzylidine-amino) guanidine was verified by both MS and 1H NMR: MS: 775.2 (M+H)+. 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.04 (6H, t), 1.81 (4H, q), 3.93–4.55 (8H, m), 5.53 (1H, m), 6.05 (1H, d), 7.52 (2H, m), 7.85 (2H, m), 7.86–8.17 (1H, m), 8.18–8.27 (1H, m), 8.30–8.51 (1H, m).

- 38.Seidler J, McGovern SL, Doman TN, Shoichet BK. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:4477. doi: 10.1021/jm030191r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]