Abstract

We present a new method to efficiently estimate very large numbers of p-values using empirically constructed null distributions of a test statistic. The need to evaluate a very large number of p-values is increasingly common with modern genomic data, and when interaction effects are of interest, the number of tests can easily run into billions. When the asymptotic distribution is not easily available, permutations are typically used to obtain p-values but these can be computationally infeasible in large problems. Our method constructs a prediction model to obtain a first approximation to the p-values and uses Bayesian methods to choose a fraction of these to be refined by permutations. We apply and evaluate our method on the study of association between 2-way interactions of genetic markers and colorectal cancer using the data from the first phase of a large, genome-wide case–control study. The results show enormous computational savings as compared to evaluating a full set of permutations, with little decrease in accuracy.

Keywords: Bayesian testing, Genome-wide association studies, Interaction effects, Permutation distribution, p-value distribution, Random Forest

1. INTRODUCTION

We consider here the problem of estimating empirical p-values for a very large number of test statistics, when the true distributions of the test statistics are unknown and when the true distributions may vary across the test statistics. The crucial assumption behind our work is that accurate approximations to the p-values are most important for the small p-values; we are willing to tolerate imprecise estimates of large p-values. Conceptually, therefore, we are building on the work of Besag and Clifford (1991) who proposed a sequential strategy for permutation tests, in which permutations were simulated until a fixed number of simulated test statistics had exceeded the observed one, so that small p-values received more permutations than did large ones.

There is one subtle difference between the motivation for our approach and that of previous sequential approaches. Others (e.g. Besag and Clifford, 1991,) define the p-value to be the Monte Carlo or empirical p-value x/N, where the observed test statistic is the xth largest when included in a random sample of N − 1 test statistics simulated under the null hypothesis. We adopt the point of view that this is just an approximation to the true p-value, that is, the value that would be obtained by enumerating the complete permutation distribution, or equivalently the limiting value of the empirical p-value as N→∞. One of the key ideas of this paper is to treat the true p-values as parameters to be estimated using computationally efficient methods.

Our work was motivated by a desire to test for interactions between haplotypes in a case–control study of genetic predictors of colorectal cancer (the ARCTIC study). This study includes approximately 1200 colorectal cases and 1200 controls from Ontario, Canada; for this research, we focus on marker genotypes at 1363 markers in 212 candidate genes. Haplotypes are sequences of marker alleles on the same chromosome for a chosen set of markers (see Table 1). We use a test of interaction similar to a recently proposed general goodness-of-fit statistic (Becker, Schumacher, and others, 2005).

Table 1.

Genotypes and potential haplotypes for 3 SNP markers. The 2 true haplotypes are ACG and TCC. However, only the genotype data are observed. Two possible haplotype pairs are consistent with the observed genotypes

| Marker 1 | Marker 2 | Marker 3 | |

| True haplotype pair | |||

| Chromosome 1 | A | C | G |

| Chromosome 2 | T | C | C |

| Observed genotypes | AT | CC | CG |

| Second potential haplotype pair | |||

| Chromosome 1 | A | C | C |

| Chromosome 2 | T | C | G |

Asymptotic estimates of statistical significance for tests of haplotype interactions are unlikely to be valid for 3 reasons. First, the haplotypes are not directly observed but are estimated from genotype data, and therefore the haplotype counts may contain fractional entries associated with the probabilities of each haplotype combination. Second, the tables tend to be very sparse, with many haplotype combinations observed rarely or at low probabilities. Third, each individual has 2 chromosomes and can therefore contribute at least twice to the counts, violating the assumption of independence. In simulations, the null distributions of our test statistics are highly variable depending on the number of sparse cells and the number of possible haplotypes.

In the statistical genetics literature, several approaches have been developed for obtaining empirical significance levels for functions of a set of p-values or test statistics. For example, Dudbridge and Koeleman (2004) showed that − ∑k = 1Rlogp(k), summing over the smallest R p-values, should follow an extreme-value distribution. The parameters of this distribution can be estimated from a reasonably sized set of permutations and can lead to increased accuracy at very small significance levels. Another approach is to work directly with the distribution of minP, the smallest p-value in a group (Becker, Cichon, and others, 2005), (, beckerSchumacher05), especially when there is a small region of interest with a limited number of markers (and hence tests). When asymptotically normal score tests can be used, Monte Carlo simulation of standard normal variates can be combined with the score tests to obtain a null distribution with the same correlation pattern as the original data (Lin, 2005), (, seaman05), this can lead to more efficient ways of estimating significance levels. All these methods depend on the ability to accurately calculate small p-values for the individual tests in the set, and this is precisely our focus in this paper.

In Section 2.1, we describe the test statistic used in our example. Section 2.2 describes a method for quickly obtaining approximate estimates of the p-values associated with the test statistics, using a Random Forest (RF) model. Then, Section 2.3 describes a Bayesian scheme for deciding which tests are of most interest and where permutations could be effectively used to improve the p-value estimates. Section 2.4 describes how this approach is evaluated. Results are shown in Section 3. The ideas behind this approach are applicable to different test statistics, and in fact, to any context where massive numbers of tests are being performed yet asymptotic significance levels are not appropriate and permutation is needed to estimate significance.

2. METHODS

For illustration of our methods, we examine tests of interactions among a very large set of haplotypes. Since haplotypes are unobserved, the popular PHASE algorithm of Stephens and others (2001) was used to estimate haplotypes within overlapping “windows” consisting of 3 adjacent markers within each gene. This choice is arbitrary, and our approaches would work for a variety of window lengths. For each window of 3 markers, there could be a maximum of 8 possible haplotypes among the cases and controls, although for any individual, only a few haplotypes are likely to have nonzero probability. We restrict our attention to interactions between those haplotype windows, where the triplets lie in different genes, and the term “window pair” will be used to refer to a particular haplotype pair, with 1 haplotype from each gene. For the data we consider here, the data from separate genes can be considered independent since 2 genes rarely lie close to each other. For each individual, the probabilities will sum to 4 (or slightly less due to rounding and truncation by PHASE), as each triplet window occurs on both copies of the chromosome, and we create all possible pairings of the windows in the 2 genes.

As described in Becker, Schumacher, and others (2005), for each interaction of 2 haplotype windows, a table of estimated counts, with a maximum dimension of 64 × 2, can be constructed from the haplotype probability distributions. Table 2 gives an example and it can be easily seen that many of the counts are very small and few of them are integers. In Section 2.1, we will make extensive use of row totals: these refer to 64 totals of probabilities for all haplotype pairs (5th and 10th columns in Table 2). We will refer to tables like Table 2 as “haplotype-pair count” tables.

Table 2.

Sample table of haplotype-pair counts, rounded to 1 decimal place

| Win1 | Win2 | Case | Control | Total | Win1 | Win2 | Case | Control | Total |

| CCC | CAC | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.4 | TCC | CAC | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| CCC | CAG | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | TCC | CAG | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| CCC | CGC | 9.5 | 6.9 | 16.4 | TCC | CGC | 4.6 | 2.9 | 7.4 |

| CCC | CGG | 4.9 | 2.0 | 6.9 | TCC | CGG | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.6 |

| CCC | TAC | 5.8 | 3.4 | 9.2 | TCC | TAC | 1.5 | 1.7 | 3.3 |

| CCC | TAG | 1.1 | 1.9 | 3.0 | TCC | TAG | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| CCC | TGC | 6.5 | 4.4 | 10.9 | TCC | TGC | 1.6 | 2.2 | 3.8 |

| CCC | TGG | 2.5 | 3.3 | 5.8 | TCC | TGG | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| CCT | CAC | 8.4 | 11.1 | 19.5 | TCT | CAC | 7.6 | 3.7 | 11.3 |

| CCT | CAG | 3.5 | 3.1 | 6.7 | TCT | CAG | 3.3 | 0.4 | 3.7 |

| CCT | CGC | 79.1 | 93.4 | 172.4 | TCT | CGC | 57.8 | 57.2 | 115.0 |

| CCT | CGG | 26.6 | 28.7 | 55.3 | TCT | CGG | 24.9 | 24.1 | 49.0 |

| CCT | TAC | 69.0 | 74.1 | 143.1 | TCT | TAC | 47.0 | 46.5 | 93.5 |

| CCT | TAG | 46.3 | 37.0 | 83.3 | TCT | TAG | 27.1 | 29.0 | 56.1 |

| CCT | TGC | 77.9 | 68.5 | 146.4 | TCT | TGC | 41.4 | 44.6 | 86.1 |

| CCT | TGG | 41.7 | 34.8 | 76.4 | TCT | TGG | 28.9 | 27.9 | 56.8 |

| CGC | CAC | 80.4 | 77.8 | 158.2 | TGC | CAC | 13.1 | 9.6 | 22.7 |

| CGC | CAG | 22.0 | 17.7 | 39.7 | TGC | CAG | 2.9 | 2.2 | 5.1 |

| CGC | CGC | 731.9 | 789.5 | 1521.4 | TGC | CGC | 107.3 | 110.9 | 218.2 |

| CGC | CGG | 293.8 | 305.0 | 598.9 | TGC | CGG | 39.5 | 43.9 | 83.5 |

| CGC | TAC | 705.6 | 660.0 | 1365.6 | TGC | TAC | 90.3 | 95.7 | 186.1 |

| CGC | TAG | 397.9 | 366.6 | 764.5 | TGC | TAG | 52.0 | 48.3 | 100.3 |

| CGC | TGC | 609.2 | 616.0 | 1225.3 | TGC | TGC | 81.3 | 75.5 | 156.8 |

| CGC | TGG | 373.7 | 355.4 | 729.1 | TGC | TGG | 39.3 | 43.7 | 83.0 |

| CGT | CAC | 7.6 | 11.4 | 19.0 | TGT | CAC | 8.6 | 8.8 | 17.4 |

| CGT | CAG | 2.9 | 2.4 | 5.3 | TGT | CAG | 2.6 | 2.8 | 5.4 |

| CGT | CGC | 83.0 | 89.5 | 172.5 | TGT | CGC | 73.5 | 78.3 | 151.8 |

| CGT | CGG | 36.5 | 25.0 | 61.5 | TGT | CGG | 39.2 | 25.8 | 65.0 |

| CGT | TAC | 64.8 | 86.9 | 151.8 | TGT | TAC | 59.7 | 77.8 | 137.5 |

| CGT | TAG | 46.7 | 42.2 | 89.0 | TGT | TAG | 49.8 | 44.5 | 94.3 |

| CGT | TGC | 65.5 | 60.2 | 125.7 | TGT | TGC | 52.9 | 50.8 | 103.7 |

| CGT | TGG | 45.0 | 28.0 | 73.0 | TGT | TGG | 38.0 | 30.3 | 68.3 |

| Total | 4949.6 | 4897.5 | 9847.1 |

2.1. A test statistic for detecting interactions

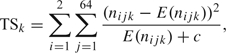

The statistic (2.1) below is proposed to test for association between the haplotype pairs and the disease state in each window pair k = 1,…,K. It is a modification of a chi-square test for independence. This statistic can detect both marginal associations for either one of the haplotypes and interactions between the 2 haplotypes and the disease. Let nijk be the counts for haplotype pair j of case (i = 1) or control (i = 2) in window pair k.

|

(2.1) |

where E(nijk) stands for the expectation of nijk under the independence hypothesis, which is calculated as

The constant c in the denominator of (2.1) was set to 0.5. This has the effect of reducing the contribution of rare haplotype pairs to TSk, similar to the effect of pooling cells with low counts.

A very similar statistic was used by Becker, Schumacher, and others (2005). Their statistic did not use the constant c in the denominator and divided the overall result by 2.0. The method described below will be appropriate for any choice of test statistic defined on data like that in Table 2; the general principles will apply to many large collections of tests.

2.2. Machine learning approach for estimating p-values

In this section, we describe how to use permutations on a small training set of window pairs to obtain initial approximations for all window pairs k = 1,…,K, based on the observed summary table of nijk counts for that pair. These estimates will then be improved by using the algorithms described in Section 2.3 to run permutations on selected window pairs.

A simple prediction strategy is used for obtaining  k. For each of the window pairs in the training set, a true null distribution is obtained by permutation of the case/control labels. This constructs a “reference set” of null distributions. A prediction rule is then defined by modeling the empirical distributions as functions of marginal characteristics of the haplotype-pair count table; this is then used to obtain

k. For each of the window pairs in the training set, a true null distribution is obtained by permutation of the case/control labels. This constructs a “reference set” of null distributions. A prediction rule is then defined by modeling the empirical distributions as functions of marginal characteristics of the haplotype-pair count table; this is then used to obtain  k from the observed statistic for all tests.

k from the observed statistic for all tests.

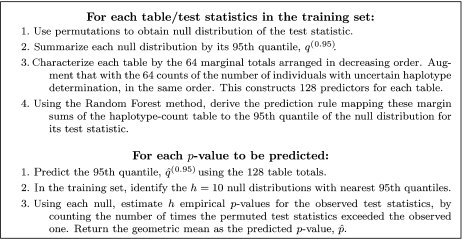

Figure 1 summarizes the p-value prediction algorithm. The motivation for using the margin counts of Table 2 as predictors is as follows. If the haplotype-pair count table were actual counts based on classifying independent individuals and all cells had nonzero expected counts, then (2.1), with c = 0, would be a standard Pearson chi-square statistic testing for independence with asymptotic null distribution χ(63)2. However, if some haplotype combinations do not occur or occur with very low frequency, then the null distribution will be better approximated with fewer degrees of freedom. The distribution might also be influenced by the proportion of individual haplotype counts to which PHASE attributed low probabilities (the dispersion of the distribution). Finally, we order the sums by their magnitudes separately for each haplotype-count table, since there is no meaningful matching of haplotypes across such tables. We use the Random Forest (RF; Breiman, 2001,) machine learning tool as implemented by Liaw and Wiener (2002) in R (R Development Core Team, 2007) for deriving predictions.

Fig. 1.

p-value prediction algorithm.

2.3. Bayesian updating of p-value estimates

We have K window pairs to examine, k = 1,2,…,K. If we wished to evaluate all p-values using N permutations of the case–control labels, we would require KN constructions of tables of nijk values and evaluations of (2.1). However, most of the K window pairs are of limited interest to us, we want to accurately estimate only the small p-values.

We start by representing the RF predictions from Section 2.2 as a prior distribution πk(·) for the true p-value pk, with details described later. We will obtain permutation draws TSkl*, l = 1,…,nk, from the null distributions for TSk. After nk permutation draws, resulting in xk simulated statistics exceeding the observed one, the posterior distribution for pk is

| (2.2) |

We want to minimize the sum of nk‘s over all window pairs, without compromising the “inferential characteristics” of the procedure.

We assume that nk may be capped by a fixed N; if we ran N permutations on all pairs, we would have sufficiently accurate determinations of the p-values to proceed with inference. We also assume that there is some target p-value, p0, and those window pairs with pk < p0 are of particular interest. (In fact, the procedure we describe below is relatively insensitive to the precise value of p0, provided it is not too large.) The relation between N and p0 is based on our precision requirements. For example, if we are interested in estimating p-values in the neighborhood of a small p0 with a standard error of p0/10, we would set N≈100/p0. In our calculations, we chose N = 104 and p0 equal to 5×10 − 5,10 − 4, and 10 − 3.

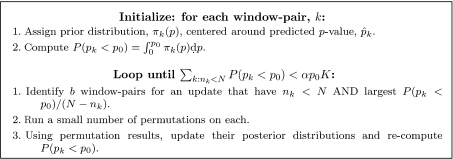

The update algorithm is presented in Figure 2. In each iteration, it attempts to maximally decrease the total estimated number of “missed” p-values that have not been estimated with full precision:

| (2.3) |

where the probabilities in (2.3) are taken with respect to the corresponding posterior density πk(·|TSk·*). By targeting window pairs with nk < N and the largest P(pk < p0)/(N − nk), we are performing a greedy minimization of Kmiss.

Fig. 2.

p-value Bayesian update algorithm. K is the number of p-values to consider, N is a cap for the number of permutations for each p-value, p0 is a target p-value, b is a batch size for the updates, and nk is the number of permutations done for window pair k so far.

We are interested in the p-values with pk < p0. Assuming a uniform distribution of pk values, we would expect p0K elements in this set; the algorithm stops when we have done the full set of permutations on all but a proportion α of these, that is, when Kmiss < αp0K. We used α = 0.01 in our simulations.

The prior distribution πk(·) needs to take into account the information coming from the RF estimation and to facilitate the computations described above. An ideal approach would be to determine the distribution of  k conditional on the true pk and combine that with prior knowledge about window pair k to compute a true posterior distribution of pk given data

k conditional on the true pk and combine that with prior knowledge about window pair k to compute a true posterior distribution of pk given data  k. However, this calculation is difficult and would likely yield integrals of (2.2) that were intractable. We sought a computationally convenient approximation.

k. However, this calculation is difficult and would likely yield integrals of (2.2) that were intractable. We sought a computationally convenient approximation.

A Beta prior is conjugate to the Bernoulli (pk) updates but we found that it did not match observations. However, a mixture of 2 Beta distributions worked well.

We used the following process to choose the parameters. First, we selected Hp = 3000 pairs at random from the full set of pairs and ran 10 000 permutations on each of them. We also computed the RF predictions for each. Then in an exploratory step, we fit the parameters of a 2-component Beta-binomial mixture with the Beta parameters (αik,βik) and component proportions γik, i = 1,2, k = 1,…,3000, all depending smoothly on  k. As described in Section 3, this resulted in fits where the parameters appeared to have fairly simple parametric relations to

k. As described in Section 3, this resulted in fits where the parameters appeared to have fairly simple parametric relations to  k; we then fit those relations and used them to assign priors to the full set of pairs.

k; we then fit those relations and used them to assign priors to the full set of pairs.

Using a mixture of Beta distributions, the posterior distribution after observing xk successes in nk trials will be a mixture of Beta(αik + xk,βik + nk − xk) distributions (i = 1,2) with component proportions γik′ = dik/(d1k + d2k), where dik = γikB(αik + xk,βik + nk − xk)/B(αik,βik). Here, B(·,·) is the Beta function.

2.4. Evaluation of model performance

We compare our 2-stage strategy, which we call BUaP (for Bayesian update after prediction) to 2 other alternatives:

Besag(n): Besag method (Besag and Clifford, 1991) run until n successes are observed.

Classical: All p-values are estimated using separate permutation exercises with N = 10000 permutations.

We need a common basis of comparison to evaluate these approaches. We suppose that one use for a p-value will be simple comparison against one or more fixed levels (or thresholds) pT. If we knew the true p-values pk and each method produced fixed estimates  k, we could define the sensitivity of a procedure at threshold pT as

k, we could define the sensitivity of a procedure at threshold pT as  and the specificity as

and the specificity as  .

.

However, we do not know the true pk values and our approach produces posterior distributions for pk, not simple estimates. But both the Besag(n) and the Classical methods allow easy posterior calculations with a uniform prior: xk successes out of nk trials produces a Beta (xk + 1,nk − xk + 1) posterior.

Thus, we adopted the following approach. We approximated the true p-values by running 10 000 permutations for all window pairs and an additional 30 000 permutations for those window pairs which had fewer than 1200 successes in the first run. (We call these the “reference permutations.”) We then imagined the following experiment: draw a window pair k at random, draw  k from the posterior distribution of pk under the method being evaluated, and independently draw pk from the posterior based on the reference permutations. The sensitivity is the conditional probability

k from the posterior distribution of pk under the method being evaluated, and independently draw pk from the posterior based on the reference permutations. The sensitivity is the conditional probability  under this sampling scheme. This conditional probability is evaluated as

under this sampling scheme. This conditional probability is evaluated as

| (2.4) |

where Ptest is the posterior arising from the approach being examined and Pref is the posterior arising from the reference permutations. Specificity is defined analogously.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Simple validation of RF p-value estimates

The RF model for predicting p-values was built on 3000 randomly chosen window pairs, for which reference p-values were obtained using 10 000 permutations. The model was then used to predict all 410 108 p-values and these predictions were compared to p-value estimates xk/nk on all window pairs based on the reference permutations described in Section 2.4. The RF procedure has a number of tuning parameters which could be used to optimize model performance. As our main goal is to provide a sensible initial p-value estimate, we have not attempted to fully optimize the RF model and have used the default settings in the R implementation of the model. We used h = 10 nearest neighbors for p-value prediction.

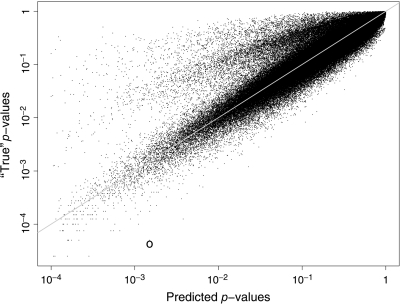

Figure 3 shows reference versus predicted p-values for all window pairs using the BUaP approach. The plot shows that the p-value prediction scheme works well; there are very few significant window pairs which would have been missed. For example, in the BUaP run described below with the p0 target equal to 10 − 4, all pairs with predicted p-values below about 0.02 were targeted at least once for permutation updates. Among all window pairs with predicted p-values over 0.02, none had a true p-value below the p0 level. The same result holds for the BUaP runs with other p0 targets. The circle in the plot displays one of the most significant overpredictions; here, a p-value was predicted over 0.001 while its true value is below 0.0001. Such instances are rare and a more common bias is to underpredict the p-value. This is likely a result of focusing the RF model on the 95th percentile and reflects our desire to optimize sensitivity of the prediction step with a consequent loss of specificity.

Fig. 3.

p-value estimates based on the reference permutations and as predicted by the RF model on all 410 181 window pairs.

The window pair from Table 2 had a test statistic equal to 35.66 with a predicted p-value of 0.785. Its reference permutation p-value was 0.85 (with 8537 successes in the first 10 000 permutations).

3.2. Prior selection in the Beta mixture model

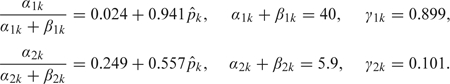

Using locally weighted maximum likelihood, we found that the Beta mean parameters αik/(αik + βik), i = 1,2, were approximately linearly related to the RF predictions  k. The sums αik + βik were highest at the extremes

k. The sums αik + βik were highest at the extremes  k = 0 or 1, indicating more concentrated distributions there, but rather than attempting a precise fit, we took a conservative approach and fixed the more precise component to have α1k + β1k = 40 (near the low end of the observed range). We then refit the model linearly in the means, with constant precision and γik, resulting in the following parameters for πk(p):

k = 0 or 1, indicating more concentrated distributions there, but rather than attempting a precise fit, we took a conservative approach and fixed the more precise component to have α1k + β1k = 40 (near the low end of the observed range). We then refit the model linearly in the means, with constant precision and γik, resulting in the following parameters for πk(p):

|

One interpretation of these parameters is that the RF fit was taken to be as informative as running somewhere between α2k + β2k = 5.9 and α1k + β1k = 40 Bernoulli trials. We emphasize that this is likely a conservative approximation to the information provided by RF.

3.3. Sensitivity and specificity of the methods

This section shows the main results of our study. Our hypothesis is that the BUaP strategy has a strong computational advantage without a large decrease in accuracy.

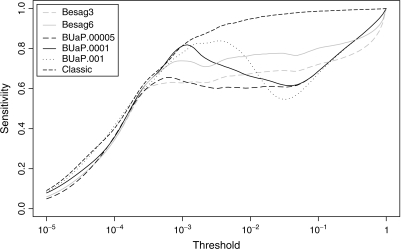

In Figure 4, we compare sensitivity across a range of p-value thresholds for the different strategies. The sensitivity curves in these plots were calculated as explained in Section 2.4. All methods have very similar sensitivities up to a threshold around 2×10 − 4; BUaP with p0 = 10 − 4 continues to rise in sensitivity up to about 10 − 3. In the crucial range of small p-values, it exceeds the sensitivity of the Besag methods. Sensitivities of different strategies.

Fig. 4.

Sensitivities of different strategies.

Table 3 compares the number of permutations needed for each method. (This does not include those used in training the BUaP methods: that would be a relatively fixed cost, the numbers shown in Table 3 could be expected to be roughly proportional to the number of tests.) We see here that BUaP with p0 = 10 − 4 required fewer permutations than Besag(3), even though its sensitivity is much higher in the low range. We also show the effect of changing p0: larger values rapidly increase the required number of permutations. Sensitivities (not shown) followed the same pattern as for p0 = 10 − 4 but the peak sensitivity moved according to the value of p0.

Table 3.

Numbers of permutations used by each strategy

| Method | Permutations (millions) |

| Besag(3) | 15.2 |

| Besag(6) | 28.7 |

| BUaP (p0 = 0.00005) | 8.4 |

| BUaP (p0 = 0.0001) | 13.4 |

| BUaP (p0 = 0.001) | 31.4 |

| Classic | 4101.8 |

| PO | 0.0 |

We also computed specificities, which were very high for all methods shown in Figure 4 (greater than 0.995 for thresholds up to 0.01).

3.4. Note on running times and computational complexity

Our method has 2 advantages: it provides an ability to focus the p-value estimation process on interesting cases while greatly reducing the total number of permutations compared to Classical and Besag approaches. We focus the discussion of computational complexity on the total number of permutations, since this is common to all methods and it contributes the lion's share of the running time. Building the RF model on the 3000 pairs took about a minute and producing all 410 108 predictions from this model about 30 min, once the full data set (i.e. 128 predictors for each pair and their corresponding test statistics) was assembled. In contrast, running BUaP (p0 = 10 − 4) took about 4 h, while Classical took about 9 days, “after” careful hand optimization of the permutation code used by Classical. As with Classical, running times of the Besag family of methods are roughly proportional to the total number of permutations required.

The BUaP method has another important computational advantage. With a large genomic data set, such as the ARCTIC data considered in this paper, one will need to process the data in chunks, repeatedly accessing a remote database server for reading and writing. Since the vast majority of pairs (about 98% for BUaP [p0 = 0.0001] in our case) do not require any permutations at all, one saves a huge amount of database traffic while still predicting all p-values. The RF predictions require only a summary table for each pair which can be precomputed and stored within the database or computed on the fly using a stored procedure. In contrast, running permutations will require transferring large amounts of individual-level data from the database.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we have used the RF algorithm to estimate p-values and then used the empirical behavior of those p-value estimates to construct prior distributions in the Bayesian estimation step. We see 2 advantages of this 2-stage approach: it modularizes the procedure so that different approaches to both prediction and Bayesian update could be used; it is much easier to use a large number of covariates to predict a single response than to predict several parameters of the prior distribution.

The output of our procedure is a posterior distribution of the p-value for each window pair. These posteriors could be used in further computations. For example, to estimate the false-discovery rate (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995), (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003) of the testing procedure, we would need an estimate of the distribution of all the p-values. This may be obtained by averaging (and perhaps smoothing) the posteriors across the full set of window pairs.

This paper has concentrated on the computation of p-values in one part of the ARCTIC project. Readers who are interested in the conclusions of that study about the relationship between genetic markers and colon cancer are referred to Zanke and others (2007).

A software package implementing the algorithm is available from the first author on request.

FUNDING

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grants to R.K. and D.J.M.; Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute, by Génome Québec, the Ministère du Développement Économique et Régional et de la Recherche du Québec and the Ontario Cancer Research Network to ARCTIC project; National Program on Complex Data Structures to R.K. and X.S. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (NSERC).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the Centre for Applied Genomics, Hospital for Sick Children. This work was made possible through collaboration and cooperative agreements with the Colon Cancer Family Registry (CFR) and PIs (RFA CA-95-011). The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute or any of the collaborating institutions or investigators in the Colon CFR, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government or the Colon CFR. Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Becker T, Cichon S, Jönson E, Knapp M. Multiple testing in the context of haplotype analysis revisited: application to case-control data. Annals of Human Genetics. 2005;69:747–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Schumacher J, Cichon S, Baur M, Knapp M. Haplotype interaction analysis of unlinked regions. Genetic Epidemiology. 2005;29:313–322. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Besag J, Clifford P. Sequential Monte Carlo p-values. Biometrika. 1991;78:301–304. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L. Random forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dudbridge F, Koeleman B. Efficient computation of significance levels for multiple associations in large studies of correlated data, including genomewide association studies. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;75:424–435. doi: 10.1086/423738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News. 2002;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lin D. An efficient Monte Carlo approach to assessing statistical significance in genomic studies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:781–787. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman S, Müller-Myhsok B. Rapid simulation of P values for product methods and multiple testing adjustment in association studies. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;76:399–408. doi: 10.1086/428140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M, Smith N, Donnelly P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;68:978–989. doi: 10.1086/319501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey J, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanke BW, Greenwood CMT, Rangrej J, Kustra R, Tenesa A, Farrington SM, Prendergast J, Olschwang S, Chiang T, Crowdy E. A colorectal cancer susceptibility locus on chromosome 8q24 identified by a genome-wide association scan. Nature Genetics. 2007;39:989–994. doi: 10.1038/ng2089. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]