Abstract

Human uterine fibroblasts (HuF) isolated from the maternal part (decidua parietalis) of a term placenta provide a useful model of in vitro cell differentiation into decidual cells (decidualization), critical for successful pregnancy. After isolation, the cells adhere to plastic and have either a small round or spindle-shaped morphology which later changes into a flattened pattern in culture. HuF robustly proliferate in culture until passage 20 and form colonies when plated at low densities. The cells express the mesenchymal cell markers fibronectin, integrin-β1, ICAM-1 (CD54), and collagen I. Flow cytometry of HuF detected the presence of CD34, a marker of hematopoietic stem cell lineage, and an absence of CD10, CD11b/Mac, CD14, CD45, and HLA type II. Furthermore, they also express the pluripotency markers SSEA-1, SSEA-4, Oct-4, Stro-1, and TRA-1−81 as detected by confocal microscopy. Treatment for 14−21 days with differentiation-inducing media led to the differentiation of HuF into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes. The presence of α-smooth muscle actin, calponin, and myosin light chain kinase in cultured HuF implies their similarity to myofibroblasts. Treatment of the HuF with DMSO causes reversion back into the spindle-shaped morphology and a loss of myofibroblast characteristics, suggesting a switch into a less differentiated phenotype. The unique abilities of HuF to exhibit multipotency, even with myofibroblast characteristics, and their ready availability and low maintenance requirements make them an interesting cell model for further exploration as a possible tool for regenerative medicine.

Keywords: placenta, adult stem cells, mesodermal lineages, myofibroblast pluripotency markers, human

Introduction

The human term placenta has been recently described as an attractive source of pluripotent “adult stem cells” (In 't Anker et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2004; Yen et al. 2005; Li et al. 2005; Portmann-Lanz et al. 2006; Battula et al. 2007). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) isolated from the placenta have similar characteristics to widely used bone marrow-derived MSC. Moreover, maternal MSC from term deciduae showed a significantly higher expansion capacity than MSCs from adult bone marrow (In 't Anker et al. 2004). Finally, their isolation from discarded placentas is non-invasive, abundant, and ethically unbiased.

Fibroblasts isolated from the maternal part (decidua parietalis) of the term placenta represent a proliferating population of non-differentiated cells, which are maintained in the decidualized uterine endometrium (Markoff et al. 1983; Richards et al. 1995). These cells were used by different investigators (Markoff et al. 1983; Richards et al. 1995; Brar AK et al. 2001; Eyal O et al. 2007; Kessler CA et al., 2006), including ourselves (Strakova et al. 2000; Ihnatovych et al. 2007), as a useful model of in vitro cell differentiation into decidual cells (decidualization). This process of differentiation is critical for successful implantation and pregnancy. We have termed them human uterine fibroblasts (HuF); they are also referred to by other investigators as decidual stromal cells.

These cells have been shown to express antigens associated with hematopoietic cells (Montes et al. 1996), although it was suggested that they are more closely related to bone marrow stromal precursors (García-Pacheco et al. 2001). Their morphology and phenotype was described to be similar to myofibroblasts (Oliver et al. 1999; Kimatrai et al. 2003), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expressing fibroblastic cells with contractile activity that are involved in wound retraction.

The purpose of our study was to further characterize the presence of pluripotency markers in HuF, as well as to evaluate the ability of HuF to differentiate into mesodermal lineages.

Materials and methods

Materials

The ES Cell Marker Sample kit (Cat#SCR002) containing antibodies for the detection of stage-specific embryonic markers (SSEA-1 and SSEA-4), tumor recognition antigens (TRA-1−60 and TRA-1−81) and Oct-4; The Mesenchymal Stem Cell Characterization kit (Cat#SCR018) for detection of integrin β1, CD54, collagen type I, fibronectin, CD14 as well as antibodies against Stro-1 (mouse monoclonal MAB4315) were from Chemicon, Millipore Corporation (Billerica, MA). Mouse monoclonal anti-human α-SMA antibody clone 1A4 was from Dako (Glastrup, Denmark). Antibodies against CD11b/Mac-1 (mouse monoclonal Cat#555386), CD34 (mouse monoclonal, Cat#555820), CD45 (mouse monoclonal, Cat#555480), CD10 (mouse monoclonal, Cat#555373) and HLA-DR, DP, DQ (mouse monoclonal, Cat#555557) were from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Monoclonal β-actin antibody clone AC 15 was purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Rabbit polyclonal antibody to MLCK was kindly provided by Dr. De Lanerolle (University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL) and its preparation and characterization was described previously (De Lanerolle et al., 1981). Vimentin antibody was from Zymed Laboratories (San Francisco, CA) and calponin antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Prolong Antifade mounting medium containing DAPI was purchased from Molecular Probes, (Eugene, OR). All cell culture supplies were obtained from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Other reagents of cell culture grade were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Itasca, IL) or Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Isolation and culture of cells from decidua parietalis of term placenta

The placenta tissue was obtained from the Human Female Reproductive Tissue bank in the Center for Women's Health and Reproduction at the University of Illinois at Chicago. All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Illinois. Human uterine fibroblasts (HuF) were isolated from the decidua parietalis dissected from the placental membranes after normal vaginal delivery at term. Decidua parietalis tissue was scraped with a cell scraper from the chorion of placental membranes and digested in 0.5% collagenase and 0.02% DNase in calcium- and magnesium-free Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) for 30 minutes at 37 °C in a shaking water bath. The supernatant was recovered and placed at 4 °C. The remaining tissue was further digested in 0.5% collagenase, 0.02% DNase, 0.1% hyaluronidase and 0.1% pronase solution in HBSS for another 30 minutes. The cell suspensions from both digestions were centrifuged at 150g for 10 minutes and the pellet was resuspended in HBSS. The suspensions were filtered through a series of nylon mesh filters of decreasing size, starting with 250μm, followed by 70 μm and then twice through 20 μm nylon mesh (Small Parts, Inc., Miami Lakes, FL). The filtrates were centrifuged at 150g for 10 minutes. The pellet of isolated cells was resuspended in phenol red-free RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 0.1mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum depleted of steroids by treatment with dextran-coated charcoal (S-FBS). Cells were seeded on 4 culture plates (100mm diameter) and placed into an incubator at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The following day, the plates were extensively washed with PBS to remove nonadherent cells (mainly decidual cells and red blood cells). At confluence, cells were trypsinized and used for experiments in passage numbers 3 to 5. The cell purity of confluent cells was assessed by immunocytochemistry using antibodies against cytokeratin (Dako, Glastrup, Denmark) and vimentin (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, CA). Cells were negative for cytokeratin, and fibroblast positivity, as estimated by vimentin staining, was greater than 97%. The cells proliferate robustly and it is possible to freeze and grow them again after defrosting. Cells undergo senescence after approximately 20 passages.

Colony forming assay

HuF cells in passages 3−4 were plated in different densities (4−10 cells/cm2 or 500 cells/cm2) in triplicate and allowed to grow in culture medium for 21d. The culture medium was exchanged every 2−3 days and the experiment was repeated three times. The cultures were stained with 1% (v/v) Crystal Violet (Sigma) in 10% ethanol for 5 minutes. The cells were washed twice with distilled water and the number of colonies with a diameter bigger than 2mm was counted using Quantity One 1-D analysis software on ChemiDoc XRS System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Flow cytometry

80−90% confluent HuF cells (p. 2−3), cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% S-FBS, were used for the analysis of cell-surface molecules. The cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and the cell suspension was adjusted to a concentration of 1.5 × 106 − 2 × 106 cells/ml in ice-cold 3% BSA/PBS. HuF cells were incubated for 2h at room temperature with mouse anti-human CD54, CD34, CD14, CD11b, CD10, CD45, HLA-DR, DP, and DQ monoclonal antibodies (1μg antibody/106 cells). Antibodies with a matching isotype were used to detect a nonspecific fluorescence. The cells were washed three times by centrifugation at 400g for 5 min and resuspending in ice-cold PBS. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in 3% BSA/PBS was applied for 30 min in the dark. After incubation, HuF cells were washed 3 times with ice-cold PBS, resuspended in 0.2 ml of 2% formalin and analyzed for the aforementioned human antigens by using a Beckman-Coulter Elite ESP flow cytometer. Cytofluorimetric data were processed with WinMDI software (Joe Trotter, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA).

Immunofluorescence staining

HuF grown on glass coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, then blocked with 5% BSA at room temperature. Incubations with primary antibodies against pluripotency markers [Oct-4, SSEA-1, SSEA-4, TRA-1−81, (all used at 1:10 concentrations), and Stro-1 (1:200)] or mesenchymal cell markers [ICAM-1 (1:100) integrin β1 (1:500), collagen I (1:500) and fibronectin (1:1500)] or mouse IgG and rabbit IgG (at appropriate concentrations, negative controls) were carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendations, followed by incubation for 1h with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:100). Coverslips were mounted with Prolong Antifade mounting medium containing DAPI. The images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 510 laser confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY).

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) detection

Cells were lysed with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carslbad, CA) and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed in a final volume of 20μl with 2 μg total cellular RNA containing 200U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). PCR primers specific for osteopontin (according to Zhang et al. 2004; 169 bp product), fatty acid binding protein-4, FABP-4 (according to Larson et al. 2004; 387bp product), and collagen II (according to Zhang et al. 2004; 394 bp product) were used in 50pmol concentration. The constitutively expressed histone H3.3 was used in 10 pmol primer concentration (primers according to Kim et al. 1998). PCR products were created using 32 cycles consisting of at 94 °C (1min), then 60 °C (55 °C for osteopontin) (2min), then 72 °C (3min), followed by 15 min of final extension at 72 °C. The PCR products were then analyzed by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels. Digital images were captured by Quantity One 1-D analysis software on ChemiDoc XRS System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Differentiation of cells into osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondrocytes

HuF cells were plated in passages 3−4 at a density 2.7 × 104 cells/cm2. After 4 days in culture (at confluency), the cells were subjected to differentiation treatments according to a variation of the original protocol of Pittenger et al. 1999. The differentiation experiments were repeated at least three times each.

Osteogenic differentiation

was achieved by incubating the cells in DMEM-high glucose (HG) medium supplemented with 5% FBS (Premium Select, Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), penicillin/streptomycin, sodium pyruvate, 50 nM dexamethasone, ascorbic acid (100μg/ml), 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate for 2 to 3 weeks. The medium was replaced every 2−3d. Cells were lysed with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carslbad, CA) for RNA preparation or washed with PBS and fixed in 10% formalin. To assess mineralization, calcium deposits in cultures were stained with 2% Alizarin Red S (Sigma) in PBS or by the von Kossa method. For von Kossa staining the fixed plates were washed with distilled water and then treated with 1% AgNO3 for 1h, washed again with distilled water, and treated with 2.5% sodium thiosulfate for 5 min. The staining was examined under a light microscope.

Adipogenic differentiation

was induced by incubating the cells in DMEM-HG medium supplemented with 5% heat inactivated FBS (Invitrogen, Carslbad, CA), penicillin/streptomycin, sodium pyruvate, insulin, transferrin, selenious acid, bovine serum albumin fraction V (ITS+1 supplement, Sigma), 1 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 mM isobutyl methylxanthine, 0.2 mM indomethacin for 7−14d. The medium was replaced every 2−3d. Cells were lysed with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carslbad, CA) for RNA preparation or washed with PBS and fixed in 10% formalin. Cytoplasmic inclusions of neutral lipids were stained for 30 min with fresh Oil-Red-O solution (stock: 0.5% in isopropanol, 3 parts stock mixed with 2 parts water and filtered through a 0.2μm filter). After washing plates with water, the lipid vacuoles were identified as bright red inclusions within the cells.

Chondrogenic differentiation

Cells were grown in a micromass pellet seeded into 15 ml conical tubes (0.25×106cells/tube). The cultures were maintained in DMEM high glucose media supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin, sodium pyruvate, 2% heat inactivated FBS, 10ng/ml TGF-β3 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml), ITS+1 supplement. The medium was replaced every 2−3d, after low-speed centrifugation of cells. After 14−21d in culture the chondrocyte pellet was fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. The presence of extracellular matrix proteoglycans was visualized with Alcian blue staining.

Treatment of cells with DMSO

HuF cells were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates and allowed to grow until confluency. The medium was exchanged into RPMI 1640 with 10% heat inactivated FBS with penicillin/streptomycin and sodium pyruvate. DMSO was added at a final concentration of 0.1%−2.5%. The medium was exchanged every 2d and the treatment with DMSO was repeated. On d8 of treatment, the experiment was terminated, HuF were rinsed twice with PBS and lysed on ice with lysis buffer as previously described (Strakova et al. 2000). The protein concentration was estimated by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Webster, TX). Equal amounts of total protein (2.5 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Following the transfer, the blots were probed with specific antibodies against α-SMA (1:8000), β-actin (1:8000), MLCK (1:3000), vimentin (1:10), and calponin (1:1000). The immunoreactive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence and digital images were captured by Quantity One 1-D analysis software on ChemiDoc XRS System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Cell viability assay

Cells growing in 6-well plates were subjected to 2.5% treatment with DMSO for 8d with regular exchanges of media every 2d as described above. The attached cells (lifted by 0.4% trypsin treatment) and freely floating cells in cell supernatants were stained with 0.05% trypan blue. Live and dead cells from at least 3 wells in 3 independent experiments were counted using a hemocytometer. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. The difference between the control and DMSO treated cells was evaluated by statistical analysis using SPSS12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). One-way ANOVA was used to test the null hypothesis, followed by a two-tailed t test for pairwise comparison.

Results

Characteristics of HuF

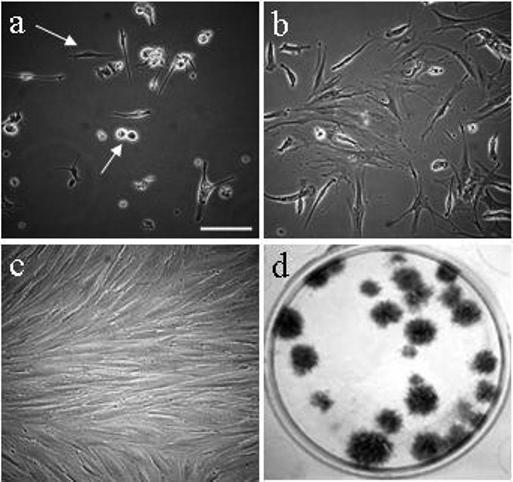

The method for isolation of HuF cells from the decidua parietalis of a term placenta is simple (digestion followed by size filtration) and the cells are cultured in common medium supplemented with dextran-coated charcoal stripped fetal bovine serum. HuF cells are extensively washed of any non-adherent cells 24h after isolation. Adherent cells have heterogeneous shapes: most with a spindle-shaped morphology (some cells showing dendrites) and lesser amounts of highly reflective small, rounded, rapidly-proliferating cells (Fig. 1a). The cells later change into a flattened pattern (Fig. 1b, d5 of culture), and confluent cells form a monolayer (passage 3, Fig. 1c). Cells are able to form colonies, when plated at a low density (passage 3, Figure 1d). For plating at a density of 4−10 cells/cm2 the average ability to form colonies was approximately 35%. An increase in the plating density to 500 cells/cm2 results in a decline in the ability to form colonies to approximately 10%.

Fig. 1. Characteristics of HuF cells.

Morphology of HuF cells on day 1 after isolation, passage 0 (a), day 5 after isolation, passage 0 (b), confluent cells in passage 3 (c). Formation of colonies as illustrated by staining of colonies formed 21d after plating 50 cells in one well of 6-well plate (d). The arrows point to spindle-like and round dividing cells (a). Images a-c were taken at same magnification. The scale bar depicted on the image (a) represents 200 m.

Flow cytometric analysis revealed a strong positivity of cells for the mesenchymal cell marker CD54 (ICAM-1), as well as CD34, an antigen detected on the precursors of hematopoietic lineage. On the other hand, there was no positivity for the common leucocyte antigen CD45, myelomonocytic antigen CD11b/Mac-1, monocyte and granulocyte marker CD14, neutral endopeptidase CD10 and major histocompatibility Class II HLA-DR, DP and most DQ antigens (data not shown).

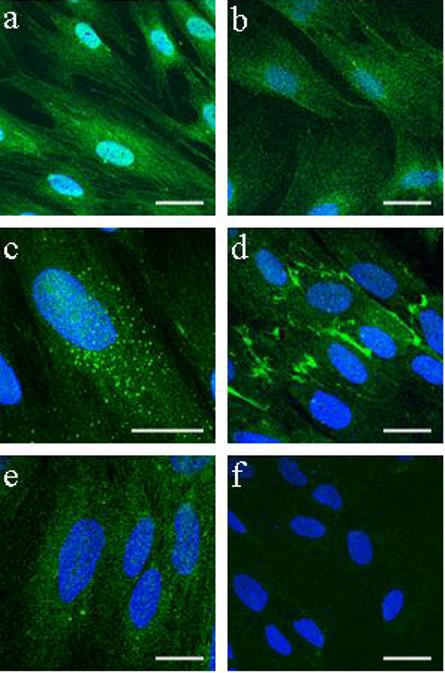

Presence of pluripotency markers Oct-4, Stro-1, SSEA-1, SSEA-4 and TRA-1−81 in HuF

Confocal microscopy of fixed cells stained with antibodies against Oct-4, Stro-1, a stage-specific embryonic antigen-1 and -4 (SSEA-1, SSEA-4), and keratin sulphate-associated antigen TRA-1−81 demonstrated the presence of these pluripotency markers in the cells (Fig. 2). We did not detect staining for TRA-1−60.

Fig. 2. Presence of pluripotency markers in HuF cells.

Confocal microscopy of immunofluorescent staining of Oct-4 (a), Stro-1 (b), SSEA-1 (c), SSEA-4 (d), TRA-1−81 (e) and negative control mouse IgG (f) in HuF cells grown on coverslips. Scale bar, 20 μm. Nuclear DAPI staining is in blue.

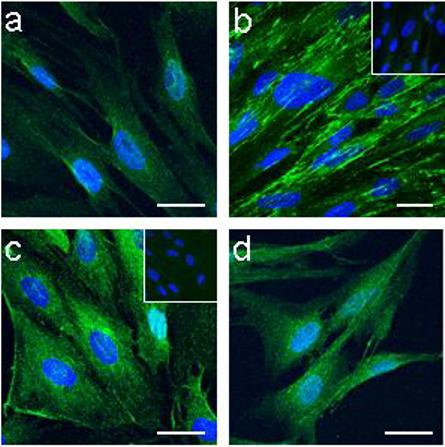

Presence of mesenchymal cell markers

The presence of ICAM-1 demonstrated by flow cytometry was further confirmed by immunocytochemical staining (Fig. 3c). In addition, HuF revealed strong positivity for collagen I (Fig. 3a), integrin β1 (Fig. 3d) and fibronectin (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Presence of mesenchymal cell markers in HuF cells.

Confocal microscopy of immunofluorescent staining for collagen I (a), fibronectin (b) ICAM-1 (CD54) (c), and integrin β1 (d). Inserts in (b) and (c) represent control rabbit IgG and control mouse IgG, respectively. Scale bar, 20 μm. Nuclear DAPI staining is in blue.

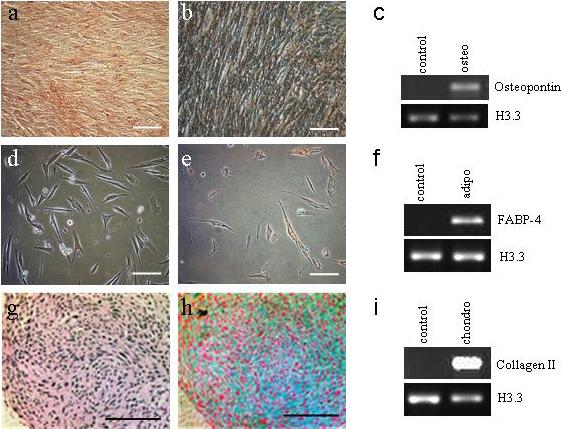

Osteogenic, adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of HuF

HuF were tested for their ability to undergo differentiation into mesenchymal lineages. After treatment with osteogenic differentiation inducing media for 14−21d, HuF cells were able to differentiate into the osteocyte phenotype. Calcium deposits in fixed cells were detected by Alizarin Red (Fig. 4a) and von Kossa (Fig. 4b) stainings. The cells cultured in osteogenic differentiation media expressed mRNA for the osteogenic marker, osteopontin, as detected by RT-PCR (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. Differentiation of HuF into osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondrocytes.

HuF cells cultured in osteogenic differentiation medium for 21d were fixed and calcium deposits were visualized by staining with Alizarin Red (a) and Van Kossa staining (b). (c) The presence of osteopontin mRNA was detected in cells cultured in osteogenic differentiation medium (osteo), but not in control cells (control). (d) Live image of HuF cells after 14d in adipogenic differentiation medium. (e) Oil-red-O staining of fixed cells treated for 14d in adipogenic differentiation medium. (f) Presence of mRNA for adipocyte marker FABP-4 detected in cells treated with adipogenic differentiation medium (adipo). Morphological analysis of cells treated for 14d with chondrogenic differentiation medium embedded in paraffin and stained with Gomori's stain (g) and Alcian blue with nuclear fast Red staining (h). (i) Presence of mRNA for collagen II detected in cells treated with chondrogenic differentiation medium (chondro). Scale bar, 100 μm.

The presence of lipid vacuoles in cells cultured in adipogenic medium for 7−14d was detected by staining with Oil-Red-O (Fig. 4e). The mRNA for the adipocyte marker FABP-4 was detected by PCR in cells treated with adipogenic medium, but was not present in the control cells (Fig. 4f).

Chondrogenic differentiation was tested in cells grown in micromass. The cells in the culture medium without factors inducing chondrogenic differentiation were dispersed and not able to sustain a cohesive mass. In contrast, the cells with media inducing chondrogenesis were sticking together and it was possible to fix the whole mass in formalin and embed it in paraffin. The presence of proteoglycans was detected in the fixed cells by staining with Alcian Blue (Fig. 4h). The mRNA for the chondrogenic marker collagen II was detected in cells treated with chondrogenic medium (Fig. 4i).

Regulation of HuF phenotype in presence of DMSO

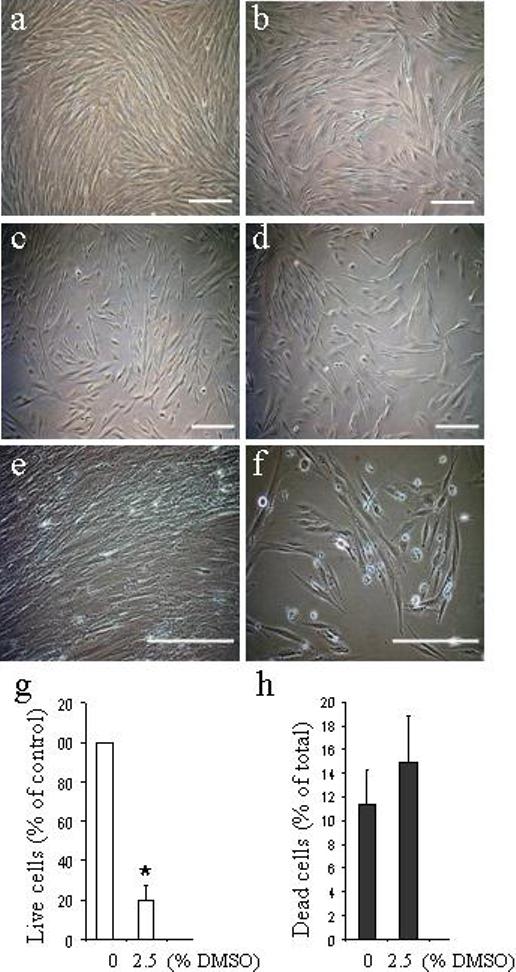

The cells growing in the long-term culture exhibit a smooth muscle-like morphology with prominent stress fibers. They spontaneously express α-SMA, the marker of smooth muscle cells. Treatment of such confluent cells with the polar solvent DMSO caused significant changes in the overall cell morphology. The morphological changes in the cells, proportional to the DMSO dose (0.5%−2.5%), were already noticeable after 24h of DMSO treatment. Under the DMSO treatment, the HuF shape changed from the original flattened pattern (Fig. 5a) to a more spindle-like or round shape (Fig. 5b-d). The round cells, after being detached from the plates by stringent washing and re-plated, were able to attach, spread, form actin filaments, and proliferate (data not shown). However, the 2.5% DMSO treatment caused a significant decline in the ability of cells to further proliferate in comparison with control (data not shown), resulting in a decrease of live cells to about 1/5th of control levels (Fig. 5g) on d8 of treatment (Fig. 5e of live control “packed” cells in comparison to 5f). Treatment of HuF with 2.5% DMSO (Fig. 5f) for 8d did not result in an increased amount of dead cells if estimated as a percentage of total cells (Fig. 5h), in comparison with untreated HuF.

Fig. 5. Regulation of HuF phenotype in presence of DMSO.

Live microscopy images of confluent HuF cells (passage 4) exposed for 24h (a-d) or 8d (e,f) to 0.5% DMSO (b), 1.25% DMSO (c) and 2.5% DMSO (d,f) or untreated (control, a,e). Scale bar, 200 μm. Graphic illustration of live (g) and dead cells (h) after 8d of DMSO treatment as estimated by trypan blue staining shown as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments done at least in triplicate. (*, p<0.05).

Changes in cytoskeletal protein expression related to cell morphology

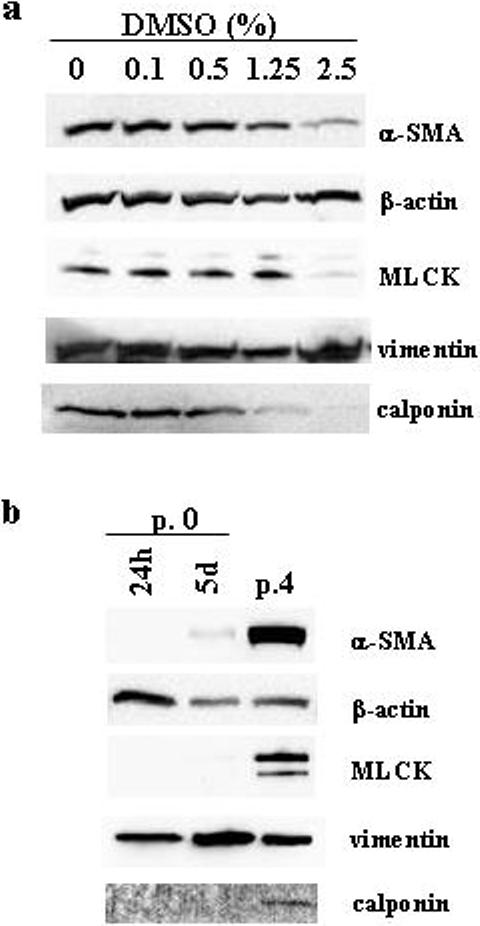

Western blot analysis of cell lysate proteins (p. 3−4) after 8d of treatment with DMSO (resulting in more spindle-like and round-shaped cells at lower cell density) demonstrated a dose-dependent decline in levels of α-SMA and the actin-binding protein calponin (Fig. 6a). HuF cells are known to express short (130kDa) and long (214 kDa) myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) isoforms (Ihnatovych et al. 2007). Treatment with DMSO caused a decline in the short form of MLCK, while the levels of cytoplasmic β-actin and the intermediate filament protein vimentin remained unchanged (Fig. 6a). The connection of the round and spindle-like phenotype (as seen in the cells 24h after isolation, passage 0, illustrated in Fig. 1a) with the lower content of α-SMA and calponin was confirmed by Western blot (Fig 6b). There was no detectable α-SMA in cell lysates from passage 0 cells, 24h after plating. However, increased time in culture (5d after isolation, p. 0) and acquisition of a flattened phenotype (as illustrated in Fig.1b) resulted in increased levels of α-SMA as well as calponin and MLCK, but unchanged levels of β-actin and vimentin (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6. Changes in cytoskeletal proteins expression related to cell morphology.

Western blot detection of α-SMA, β-actin, MLCK, vimentin and calponin in total HuF (p. 4) cell lysates (2.5 μg protein) after 8d of treatment with different DMSO concentrations. Distribution of α-SMA, β-actin, MLCK, vimentin and calponin in total HuF (p. 0) cell lysates (2.5 μg protein) after 24h (24h), 5d (5d) after cell isolation (passage 0, p.0) or in passage 4 (p. 4).

Discussion

The human placenta is an organ with a maternal and a fetal portion. In this paper we describe novel properties of the cells isolated from the maternal part of the placental membrane - the decidua parietalis. Because of their ability to differentiate into decidual cells, these cells were used for many years as a model system of in vitro decidualization (Markoff et al. 1983; Richards et al. 1995; Strakova et al. 2000; Brar AK et al. 2001; Kessler CA et al. 2006; Eyal O et al. 2007; Ihnatovych et al. 2007). They are easy to obtain from the human term placenta. They have non-demanding culture requirements and they consistently show similar properties.

The cells contain mesenchymal cell markers (integrin β1, ICAM-1, collagen I, fibronectin, vimentin) much like those observed in mesenchymal cells from bone marrow (Conget et al. 1999; Seshi et al. 2000; Silva et al. 2003). However, the flow cytometric analysis of HuF detected positive antibody binding for CD34. The presence of this early hematopoietic marker was not described in MSC isolated from fetal parts of the placenta (Zhang et al. 2004; Portmann-Lanz et al. 2006), but it was similarly observed in isolations from first trimester human decidua parietalis (García-Pacheco et al. 2001).

This is the first report of expression of the stem/progenitor cell markers SSEA-1, SSEA-4, Oct-4, Stro-1, and TRA-1−81 in cells isolated from the maternal part (decidua parietalis) of placental membranes. The presence of Oct-4, SSEA-4, and TRA-1−81 were described on MSC derived from the whole placenta (Yen et al. 2005, Battula et al. 2007), or from amniotic fluid (Delo et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2007). The presence of pluripotency markers, as well as hematopoietic and mesenchymal markers on HuF, suggest that these cells are less differentiated than classical bone marrow derived MSC.

The initial culture of HuF contains a majority of spindle-shaped cells and a minority of small round cells rapidly proliferating, similar to what was described in cultures of MSC from bone marrow (Prockop et al. 2001; Colter et al. 2000; Colter et al. 2001). It was suggested that these small, rapidly self-renewing cells (RS) are apparently the earliest progenitors and the most rapidly replicating cells in cultures of MSCs (Prockop et al. 2001).

The changes in the cell morphology (from spindle-like to a flattened pattern) with increasing time in culture are connected to changes in the cytoskeleton. α-SMA is required for the initial formation of the cortical filament bundles in spreading rat lung myofibroblasts (Hinz et al. 2003). In contrast to the ubiquitously expressed cytoplasmic γ and β non-muscle actins, α-SMA is a tissue specific actin isoform (Khaitlina et al. 2001). During lung myofibroblast cell spreading, the rate of incorporation of α-SMA into actin filaments is much slower than the incorporation of β-actin (Khaitlina et al. 2001). This agrees with our observation that there is no detectable α-SMA, MLCK or calponin in the initial spindle-shaped and round cells after isolation, but the expression of these proteins increases as the cells spread into a flattened pattern and actin fibers appear. It is notable that levels of the ubiquitously expressed β-actin or the intermediate filament protein vimentin are detectable in cells just after isolation.

The expression of α-SMA, which is apparent in HuF during long term cell culture, is considered to be a phenotypic marker for myofibroblasts (Wang et al. 2006). The term ‘myofibroblast’ was proposed many years ago for fibroblastic cells located within granulation tissue and exhibiting an important cytoplasmic microfilamentous apparatus (Gabbiani 2003). The myofibroblasts are present in healing wounds, scars, and fibrocontractive lesions where they contribute to fibrosis (Wang et al. 2006). The presence of α-SMA was not detected in mesenchymal progenitor cells isolated from the placenta, where placental membranes were removed (Zhang et al. 2004). We are demonstrating that even with myofibroblast characteristics (presence of α-SMA and other markers of smooth-muscle cells), the HuF cells are able to further differentiate into mesenchymal lineages of osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondrocytes, displaying their plasticity and multipotency.

DMSO is an efficient solvent for water-insoluble compounds. It is frequently used in biological studies and in cryopreservation of various cell types. DMSO was approved in the USA by the Federal Drug Administration in 1977 as an intravesical therapy for patients with interstitial cystitis, demonstrating a therapeutic benefit in approximately 50−70% of cases (Moldwin et al. 2007). In spite of its clinical application, the mechanism of DMSO action is still poorly understood.

Numerous cellular and molecular effects of DMSO have been reported, including its effect on cell differentiation (please see review by Santos et al. 2003). Depending on the cell type, DMSO either induced or inhibited cell differentiation. In HuF cells, changes in cells induced by DMSO are connected with a loss of α-SMA, the short isoform of MLCK, and calponin, while β-actin and vimentin remain in uniform amounts. A similar transition to a less differentiated state after DMSO treatment was described in myofibroblasts originating from bone-marrow derived MSC with mTOR suggested as a participant in the transition regulation (Hegner et al. 2005). It was proposed that regulating the phenotype of human MSCs may be of relevance for novel therapeutic approaches in arterosclerosis and intimal hyperplasia after vascular injury (Hegner et al. 2005).

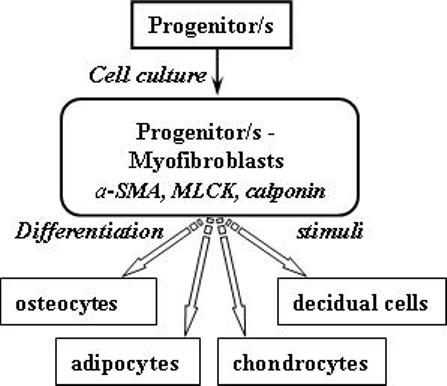

In conclusion, we suggest that myofibroblast-like HuF cells may provide an interesting cell model (please see Fig. 7) to further explore as a possible tool for regenerative medicine. This is based upon their easy availability from the term placenta, low maintenance requirements for cell culture, and their capacity to differentiate into decidual cells, osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes.

Fig. 7. Proposed model of HuF differentiation.

Huf cells (p. 0) in the progenitor form exhibit a spindle-like or rounded morphology after isolation. They do not express cytoskeletal proteins (α-SMA, calponin, MLCK). After longer terms in cell culture (p. 3−4), they express mesenchymal markers (ICAM-1, integrin β1, fibronectin, collagen I) and are CD34 positive. However, they still retain stem/progenitor cell markers (Oct-4, SSEA-1, SSEA-1, Stro-1, TRA-1−81). Their morphology changes to a flattened pattern and they also exhibit myofibroblast characteristics (positive for α-SMA, calponin, MLCK). These myofibroblast-like cells are able to further differentiate into osteocytes, adipocytes, chondrocytes and decidual cells when cultured in specific media.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD-44713 (to Z. S.). We thank S. Ferguson-Gottschall for obtaining placenta and cell preparation, P. Mavrogianis for expert technical assistance with histology and Dr. K. Narayanan for helpful technical advice.

References

- Battula VL, Bareiss PM, Treml S, Conrad S, Albert I, Hojak S, Abele H, Schewe B, Just L, Skutella T, Bühring HJ. Human placenta and bone marrow derived MSC cultured in serum-free, b-FGF-containing medium express cell surface frizzled-9 and SSEA-4 and give rise to multilineage differentiation. Differentiation. 2007;75:279–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brar AK, Handwerger S, Kessler CA, Aronow BJ. Gene induction and categorical reprogramming during in vitro human endometrial fibroblast decidualization. Physiol Genomics. 2001;7:135–48. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00061.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colter DC, Class R, DiGirolamo CM, Prockop DJ. Rapid expansion of recycling stem cells in cultures of plastic-adherent cells from human bone marrow. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3213–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070034097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colter DC, Sekiya I, Prockop DJ. Identification of a subpopulation of rapidly self-renewing and multipotential adult stem cells in colonies of human marrow stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7841–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141221698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conget PA, Minguell JJ. Phenotypical and functional properties of human bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:67–73. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199910)181:1<67::AID-JCP7>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lanerolle P, Adelstein RS, Feramisco JR, Burridge K. Characterization of antibodies to smooth muscle myosin kinase and their use in localizing myosin kinase in nonmuscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:4738–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delo DM, De Coppi P, Bartsch G, Atala A. Amniotic fluid and placental stem cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;419:426–38. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)19017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyal O, Jomain JB, Kessler C, Goffin V, Handwerger S. Autocrine prolactin inhibits human uterine decidualization: a novel role for prolactin. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:777–783. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast in wound healing and fibrocontractive diseases. J Pathol. 2003;200:500–503. doi: 10.1002/path.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Pacheco JM, Oliver C, Kimatrai M, Blanco FJ, Olivares EG. Human decidual stromal cells express CD34 and STRO-1 and are related to bone marrow stromal precursors. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:1151–1157. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.12.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegner B, Weber M, Dragun D, Schulze-Lohoff E. Differential regulation of smooth muscle markers in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1191–1202. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000170382.31085.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B, Dugina V, Ballestrem C, Wehrle-Haller B, Chaponnier C. Alpha-smooth muscle actin is crucial for focal adhesion maturation in myofibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2508–2519. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihnatovych I, Hu W, Martin JL, Fazleabas AT, de Lanerolle P, Strakova Z. Increased phosphorylation of myosin light chain prevents in vitro decidualization. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3176–3184. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In 't Anker PS, Scherjon SA, Kleijburg-van der Keur C, de Groot-Swings GM, Claas FH, Fibbe WE, Kanhai HH. Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells of fetal or maternal origin from human placenta. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1338–1345. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler CA, Schroeder JK, Brar AK, Handwerger S. Transcription factor ETS1 is critical for human uterine decidualization. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12:71–76. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaitlina SY. Functional specificity of actin isoforms. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;202:35–98. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)02003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lee Y, Kim H, Hwang KJ, Kwon HC, Kim SK, Cho DJ, Kang SG, You J. Human amniotic fluid-derived stem cells have characteristics of multipotent stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2007;40:75–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Jaffe RC, Fazleabas AT. Comparative studies on the in vitro decidualization process in the baboon (Papio anubis) and human. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:160–168. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimatrai M, Oliver C, Abadía-Molina AC, García-Pacheco JM, Olivares EG. Contractile activity of human decidual stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:844–849. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson BL, Vuoristo JT, Cui JG, Prockop DJ. Adipogenic differentiation of human adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma (MSCs). J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:256–264. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CD, Zhang WY, Li HL, Jiang XX, Zhang Y, Tang PH, Mao N. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from human placenta suppress allogeneic umbilical cord blood lymphocyte proliferation. Cell Res. 2005;15:539–547. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoff E, Zeitler P, Peleg S, Handwerger S. Characterization of the synthesis and release of prolactin by an enriched fraction of human decidual cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;56:962–968. doi: 10.1210/jcem-56-5-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldwin RM, Evans RJ, Stanford EJ, Rosenberg MT. Rational approaches to the treatment of patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2007;69:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes MJ, Alemán P, García-Tortosa C, Borja C, Ruiz C, García-Olivares E. Cultured human decidual stromal cells express antigens associated with hematopoietic cells. J Reprod Immunol. 1996;30:53–66. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(96)00954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver C, Montes MJ, Galindo JA, Ruiz C, Olivares EG. Human decidual stromal cells express alpha-smooth muscle actin and show ultrastructural similarities with myofibroblasts. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1599–1605. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.6.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portmann-Lanz CB, Schoeberlein A, Huber A, Sager R, Malek A, Holzgreve W, Surbek DV. Placental mesenchymal stem cells as potential autologous graft for pre- and perinatal neuroregeneration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:664–673. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ, Sekiya I, Colter DC. Isolation and characterization of rapidly self-renewing stem cells from cultures of human marrow stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2001;3:393–396. doi: 10.1080/146532401753277229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards RG, Brar AK, Frank GR, Hartman SM, Jikihara H. Fibroblast cells from term human decidua closely resemble endometrial stromal cells: induction of prolactin and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 expression. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:609–615. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos NC, Figueira-Coelho J, Martins-Silva J, Saldanha C. Multidisciplinary utilization of dimethyl sulfoxide: pharmacological, cellular, and molecular aspects. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:1035–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshi B, Kumar S, Sellers D. Human bone marrow stromal cell: coexpression of markers specific for multiple mesenchymal cell lineages. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2000;26:234–246. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2000.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva WA, Covas DT, Panepucci RA, Proto-Siqueira R, Siufi JL, Zanette DL, Santos AR, Zago MA. The profile of gene expression of human marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2003;21:661–669. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-6-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakova Z, Srisuparp S, Fazleabas AT. Interleukin-1β induces the expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 during decidualization in the primate. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4664–4670. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zohar R, McCulloch CA. Multiple roles of alpha-smooth muscle actin in mechanotransduction. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen BL, Huang HI, Chien CC, Jui HY, Ko BS, Yao M, Shun CT, Yen ML, Lee MC, Chen YC. Isolation of multipotent cells from human term placenta. Stem Cells. 2005;23:3–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li C, Jiang X, Zhang S, Wu Y, Liu B, Tang P, Mao N. Human placenta-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells support culture expansion of long-term culture-initiating cells from cord blood CD34+ cells. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:657–664. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]