Abstract

Colon muscle strips and cells from female patients with slow-transit constipation (STC) exhibit impaired motility, signal transduction abnormalities characterized by downregulation of Gq/11 and upregulation of Gs proteins, decreased cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and thromboxane (Tx)B2 levels, increased COX-2 and PGE2 levels, and overexpression of progesterone receptors (PGR). Progesterone (P4) treatment of normal cells reproduced these motility and signal transduction abnormalities. The purpose of the study was to examine whether overexpression of PGR-B reproduces these abnormalities by rendering the cells more sensitive to physiological concentrations of P4. Cultured human colon muscle was transfected with a plasmid DNA expressing PGR-B. The mRNAs of PGR, COX-1, COX-2, and Gq/11 were determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Their protein expression was determined by Western blot, and prostaglandins were measured by radioimmunoassay. Cultured muscle cells maintained their phenotypic features determined with myosin light chain (MLC) and h-caldesmon antibodies. Control and transfected muscle cells responded to 10−6 M P4. In contrast, muscle cells transfected with PGR-B responded to lower P4 concentration (10−7 M). This P4 concentration reduced MLC phosphorylation induced by CCK-8 (10−8 M), downregulated Gq/11, and decreased COX-1 and TxB2 levels. It upregulated Gs proteins. It also increased COX-2 and PGE2 levels. We conclude that overexpression of PGR-B renders the cells more sensitive to physiological concentrations of P4. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that overexpression of PGR-B contributes to the motility and signal transduction abnormalities observed in female patients with STC and normal serum levels of P4.

Keywords: G proteins, cyclooxygenase enzymes, prostaglandins

idiopathic constipation is prevalent in young women and is characterized by slow transit time (3, 16, 41). Female sex hormones have been suggested as possible etiologic factors in the pathogenesis of slow-transit constipation (STC) because of the higher incidence of constipation in young women than in men (29, 35) as well as during the last two trimesters of pregnancy, when the levels of progesterone (P4) are highest (2, 5, 11, 13, 26, 28, 42). This type of constipation correlates with prolonged gastrointestinal transit time (14, 22). Some studies have also shown that colonic transit time is longer during the luteal phase than during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (1, 39, 40). Furthermore, the propagation velocity of phase III in the small intestine in young women is slower in both phases of the menstrual cycle compared with men (4). However, the correlation between abnormal bowel patterns and the menstrual cycle is controversial (36). Despite these controversies, these observations suggested that sex hormones, particularly P4, which relax gastrointestinal and other smooth muscle cells (7, 33), may contribute to sex differences in the prevalence of STC in young women. However, the serum P4 levels in female patients with STC are normal (21). These conflicting data may be due to the inclusion of mixed female populations with a variable sensitivity to serum P4 levels caused by differing gastrointestinal smooth muscle responsiveness to this hormone. Variable sensitivity of colonic muscle cells to P4 may also explain why the incidence of constipation during pregnancy is ∼20% despite the high P4 levels in the last two trimesters.

We previously showed (43) that muscle strips from the colon of female patients with STC have a reduced basal motility index and an impaired muscle contraction in response to agonists that act on G protein-coupled receptors such as cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK-8) and ACh or to GTPγS, which stimulates G proteins directly. The reduced motility index is associated with lower levels of cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 mRNA and protein expression as well as decreased levels of thromboxane (Tx)B2 and PGF2α, prostaglandins (PGs) that contract colonic muscle cells (10). Reduced motility is also associated with higher mRNA and protein expression of COX-2 levels as well as higher concentrations of PGE2, a PG that relaxes colonic circular muscle cells. We have also shown that the impaired contraction in response to CCK-8 and ACh is associated with downregulation of Gq/11 proteins. Receptors that mediate muscle contraction couple with this G protein, since antibodies against Gq/11 protein block agonist-induced contraction. However, these muscle cells contract normally when stimulated by agonists that are receptor- and G protein independent such as potassium chloride or by diacylglycerol, which bypasses receptors and G proteins to stimulate protein kinase C (8). The defective muscle contraction is also associated with upregulation of Gs proteins and increased muscle relaxation in response to VIP and other inhibitory neurotransmitters whose receptors couple with this protein (15). However, muscle cells relax normally when stimulated with cAMP that is G protein independent.

P4 acts on two nuclear receptors, A and B, with each one appearing to have specific functions (15, 27). Receptor B appears to be responsible for P4-induced downregulation of Gq/11 protein that mediates agonist-induced contraction and receptor A for the upregulation of Gs proteins that mediate agonist-induced relaxation. It is therefore conceivable that overexpression of P4 receptors, particularly receptor B, by altering the signal transduction that mediates muscle contraction may contribute to the development of STC.

Whether the motility and signal transduction abnormalities detected in women with STC are caused by an overexpression of P4 receptors (PGR) in the colon, however, is not known. Muscle cells from control female subjects with normal expression of PG do not respond to physiological serum concentrations of P4 and therefore do not develop STC. In the present studies we therefore examined the hypothesis that overexpression of PGR induced by transfecting normal human colon muscle cells with PGR-B renders these cells more sensitive to physiological levels of P4. In these muscle cells with overexpressed PGR-B, concentrations of P4 that normally do not affect healthy human colon muscle cells impair myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation (the molecular basis of contraction) in response to CCK-8 and alter the signal transduction that is observed in colon muscle cells from female patients with STC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens were obtained from healthy margins of colonic resections from four female patients with adenocarcinoma of the colon, age 53–62 yr, treated at the Rhode Island Hospital. None of the patients had a history of constipation or was taking drugs that affect the gastrointestinal motility. None of the patients had any neuromuscular or collagen disorders. The muscle cells were obtained from the descending sigmoid colon away from the area involved by the carcinoma. Muscle cells from each colon specimen were kept separately, and control and experimental results were obtained in muscle cells from the same specimen. The Human Protection Committee of the Rhode Island Hospital approved the study.

Isolation and culture of human colon smooth muscle cells.

Smooth muscle cells were cultured according to a previously described method (23, 24, 30, 31). Immediately upon resection muscle tissues were transported to the motility research laboratory in ice-cold RPMI 1640 medium and incubated with 95% ethanol for 3 min. The specimen was then washed three times with RPMI 1640 and kept overnight at 4°C. The next day, removing the serosal and mucosal layers carefully isolated the circular muscle layer. The tissue was incubated with 0.2% trypsin at 37°C for 30 min in a shaking water bath, after which the tissue was again cleaned with a cotton swab (Q-tip) to ensure complete removal of the inner and outer layers. The tissue was finely minced with scissors, resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% collagenase, and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in a shaking water bath to allow dissociation of the muscle cells. The suspension was centrifuged at 900 g for 5 min, and the pellet was resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS and centrifuged at 250 g for 5 min to remove fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and tissue debris. The supernatant containing the muscle cells was cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS in a humidified atmosphere of 95% O2-5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every 3 days. Once cell confluence was attained, primary cultures were seeded at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/ml. All subsequent studies were performed on first-passage cultured cells on the third to fifth days of culture, at which time the cells attained confluence. The purity of the smooth muscle cells was identified by immunostaining an aliquot of the cell preparation with antibodies against myosin heavy chain (MHC) kinase (17–20, 32, 34) (Fig. 1) and against h-caldesmon (6, 20). These antibodies demonstrated that the cells retain the phenotypic characteristic of smooth muscle cells. These cells express the phenotypic characteristics of colon smooth muscle as determined by immunostaining for smooth muscle markers using MHC kinase and by Western blot for the expression of h-caldesmon, a protein that is specific to smooth muscle cells (37, 38). In addition, an increase in myosin phosphorylation in response to 10−5 M CCK-8 was measured in freshly dissociated and cultured cells. There were no differences in the optical density-to-milligram of protein ratio of the h-caldesmon protein bands determined by a monoclonal antibody or by the magnitude of myosin phosphorylation induced by CCK-8 between freshly isolated and cultured cells. Endothelial cells and neurons were not detected in these cultures. Furthermore, fibroblasts or endothelial cells lack h-caldesmon protein and do not respond to CCK-8.

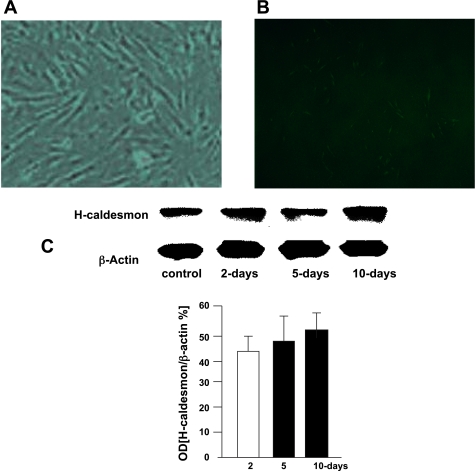

Fig. 1.

Optical microscopy (optical density, OD) showing the presence of dissociated culture colon muscle cells demonstrating the phenotypic features of human colon muscle cells. A: presence of myosin heavy chain (MHC) is shown by an antibody against MHC in cultured muscle cells and detected with a secondary fluorescence-labeled antibody. A goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC secondary antibody highlighted in green the presence of the antibody against MHC (A) compared with a negative control without secondary antibody (B). C: these phenotypic features were also demonstrated with a specific antibody against h-caldesmon proteins. Western blot analysis shows that the specific antibody against h-caldesmon detected no differences in OD of h-caldesmon between freshly dissociated muscle cells (control) and cells cultured for 2, 5, and 10 days.

Transfection of human colon smooth muscle cells.

Human PGR-A and -B cDNA was ligated into the pcDNA 3.1 vector (graciously provided by Dr. L. J. Blok, NV Organon, Oss, The Netherlands) that expressed the genes of PGR-A and PGR-B (10, 12, 25). Parallel cultures seeded with 105 cells/well (35 mm2) were transiently transfected with 2 μg of plasmid DNA expressing PGR and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The use of Lipofectamine 2000 resulted in transfection efficiencies of 70–80% in smooth muscle cells, as demonstrated by cotransfection with a green fluorescent protein reporter construct and fluorescence microscopy. In cells transfected with pLuc, assays of luciferase activity (Promega, Madison, WI) demonstrated peak levels of gene expression 24–48 h after the transfer of the gene.

For studies using Gq/11 antibody, colon muscle cells were permeabilized with saponin (75 mg/ml) for 3 min according to previously described methodology (10, 43). Permeable cells were then treated with the antibody for 1 h before treatment with PG, and the results were compared with permeable cells treated with P4 alone.

Immunocytochemistry.

Muscle cells were seeded and cultured in chamber slides (Nunc, Rochester, NY) to be used for immunocytochemistry (9). The cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and placed on slides to be dried out completely and fixed in −20°C acetone for 10 min. The cell area was labeled by encircling it with a PAP pen. The slides were then washed three times with fresh PBS buffer, and the sections were incubated with 3% blocking serum for 30 min. After the blocking serum was rinsed from the slides, the primary antibody was quickly added and incubated for 60 min. After the slides were washed three times with PBS, they were incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 min. They were again washed three times with PBS and then examined with fluorescence microscopy. The primary antibody was MHC(G-4) raised against full-length smooth muscle MHC (data not shown). h-Caldesmon was determined by Western blot analysis using monoclonal antibodies (C-4562) (Fig. 1).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) studies were performed according to a previously published methodology (10, 12). qPCR was used to measure the quantity of mRNA of PGR-A and PGR-B, Gq/11 protein, and COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes. S18 measurements were performed in parallel to determine the relative levels of each mRNA expressed as a ratio (e.g., mRNA PGR-B/S18). Total RNA was isolated from smooth muscle cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples containing 2 μg of RNA were reverse transcribed with a Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen, catalog no. 18080044) and oligo (dT)12-18 primer (Invitrogen). PCR amplifications were performed in 25-μl reactions containing 2 μl of cDNA of samples, 0.5 μM each of gene specific forward and reverse primers, and 21 μl of Platinum PCR Supermix (Invitrogen, catalog no. 11306-016). Reactions were carried out in a PTC-100 Programmable Thermal Controller (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) for one cycle at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. The RT-PCR products were determined in 2% agarose gel.

RT-PCR studies.

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) from control or P4-treated muscle cells (10, 43); 1.5 μg of total RNAs was reverse transcribed with a Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System Kit for RT-PCR (Invitrogen).

The primers for PGR-A and PGR-B, COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes, Gq/11 proteins, S18, and GAPDH are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in detection of mRNAs of PGR-A/B, COX-1, COX-2, Gq/11, GAPDH, and S18

| Product | Direction | Primer | Size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGR-AB | Forward | TGGAAGAAATGACTGCATCG | |

| Reverse | TAGGGCTTGGCTTTCATTTG | 195 | |

| PGR-B | Forward | ACACCTTGCCTGAAGTTTCG | |

| Reverse | CTGTCCTTTTCTGGGGGACT | 196 | |

| COX-1 | Forward | CCTCATGTTGCCTTCTTTGC | |

| Reverse | GGCGGGTACATTTCTCCATC | 207 | |

| COX-2 | Forward | ACCATCAATGCAAGTTCTTCCCGC | |

| Reverse | TGCAGTGGCTCCACCACCTTAATA | 889 | |

| Gq/11 | Forward | ACAAGTACGAGCAGAACAAGGCCA | |

| Reverse | AGGGCGACGAGAAACATGATGGAT | 394 | |

| GAPDH | Forward | TGAACGGGAAGCTCACTGG | |

| Reverse | TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA | 307 | |

| S18 | Forward | AGACTGTGTCCCTGTGGAGA | |

| Reverse | GGACACGGACAGGATTGACA | 50 |

PGR, progesterone receptor; COX, cyclooxygenase.

Myosin light chain phosphorylation.

Smooth muscle cells with or without plasmid cDNA PGR-A or -B were serum starved for 12 h, followed by treatment with P4 for 6 h (18). The cells were then stimulated with CCK-8 (10−8 M) for 30 s. They were washed once in cold PBS and lysed in Laemmli buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol) containing protease inhibitors [1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM NaF, 0.5 mM Na3VO4]. The extraction was added to 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) transfer membrane (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA). After the nonspecific binding sites were blocked with SuperBlock-TBS (Pierce, Rockford, IL), the blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with an antibody against phosphorylated MLC (MLC-p; 1:400). After the blots were washed, the immunoreactivity was detected with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated IgG (Pierce), an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Amersham International), and film autoradiography. Immunoreactivity was quantified with a Kodak Digital Science Image Station. The loading difference of MLC-p bands was normalized by reblotting the membranes with an antibody against total MLC (1:400). The signal density was measured, analyzed with NIH Image analysis software (version 1.55), and expressed as the ratio of MLC-p to total MLC.

Western blot analysis.

Cell lysates were prepared in M-PER mammalian protein extraction buffer (Pierce, catalog no. 78503). The supernatants obtained after centrifuging the samples at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C were used for Western blot analysis. Protein concentration was measured by colorimetric analysis (Bio-Rad, Melville, NY) according to the method of Cheng et al. (9). Proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF transfer membrane (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences), and nonspecific binding sites were blocked with SuperBlock-TBS (Pierce). The membranes were then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation. The immunoreactivity was detected with HRP-conjugated IgG (Pierce), an ECL kit (Amersham International), and film autoradiography. Immunoreactivity was quantified with a Kodak Digital Science Image Station.

PGE2 and TxB2 measurements.

Cell lysates were prepared in M-PER mammalian protein extraction buffer (Pierce) (10). The supernatants obtained after centrifuging the samples at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C were used for PGE2 and TxB2 measurements. PGE2 and TxB2 concentrations were quantified with PGE2 and TxB2 Competitive Enzyme Immunoassay kits (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

Drugs and chemicals.

CCK-8 was obtained from Bachem (Torrance, CA); P4 and antibodies against h-caldesmon and MHC kinase (C-4562) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); antibodies against the G protein subunit, COX-1, COX-2, MLC, and MLC-p were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); PCR primers were purchased from Invitrogen; plasmids containing PGR were kindly provided by Dr. L. J. Blok, Department of Reproduction and Development, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Statistical analysis.

On the basis of previous work with colon muscle cells, we found statistically significant differences between control and experimental samples by using three or four samples per experiment. In this study, each sample (n = 1) was obtained from a different colon specimen. The number of experiments to achieve significance was chosen based on our previous experimental work and by performing coefficient of variation analyses in the same muscle strips and cell samples. The present studies were performed in triplicate in cells from the same specimen. Statistical analysis was performed by one- and two-factorial repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing values between transfected muscle cells with PGR-B and control muscle cells (buffer, culture medium, empty vector, and transfection with PGR-A). P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

RESULTS

Maintenance of the phenotypic characteristics of human colon muscle cells was demonstrated in cultured muscle cells by using two antibodies against key smooth muscle cell proteins and by the ability to respond to CCK-8. We used antibodies against MHC (G-4, s-6956, Santa Cruz) and against h-caldesmon (C-4562, Santa Cruz, CA). The presence of the antibody against MHC in these cultured muscle cells was detected by using a fluorescence-labeled secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC; Sc-2010, Santa Cruz). This secondary antibody highlighted in green the presence of the antibody against MHC in muscle cells (Fig. 1, A and B). h-Caldesmon protein was determined by Western blot analysis using a monoclonal antibody. There were no differences in the optical density-to-protein ratio of h-caldesmon protein between freshly dissociated muscle cells and cultured cells up to 10 days (Fig. 1C). Moreover, CCK-8 increased the myosin phosphorylation in freshly dissociated muscle cells and cultured muscle cells. These phenotypic features are absent in fibroblasts or myofibroblasts.

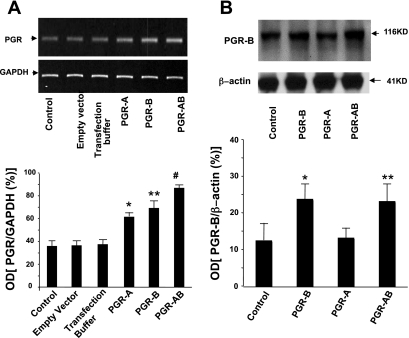

Colon muscle cells were transfected with a plasmid DNA of PGR-A or PGR-B and with both PGR-A and PGR-B after 48 h in tissue culture. The transfection increased the mRNA levels of PGR-B determined by qPCR expressed as PGR-to-S18 ratios (Fig. 2) and by RT-PCR expressed as PGR-B-to-GADPH ratios (Fig. 3) compared with controls (basal levels, tissue culture medium, and empty vectors). Western blot studies also confirmed that transfection increased the protein expression of receptor B in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B compared with controls (muscle cells treated with tissue culture medium only or with empty vectors). The protein level of PGR-B was higher than in controls when the muscle cells were transfected with a vector containing PGR-B or with PGR-AB (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Progesterone (P4) receptor (PGR)-B in colon muscle cells transfected with a plasmid containing DNA of PGR-B and PGR-AB for 48 h in tissue culture. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) shows that the expression of PGR-B is significantly higher compared with that of controls (incubated with buffer, tissue culture medium, or empty vector) (*,**P < 0.005, determined by ANOVA). Values are means ± SE; n = 4.

Fig. 3.

RT-PCR and Western blot detected the presence of PGR in freshly dissociated muscle cells (controls) and in cells cultured in tissue medium with empty vector or transfection buffer or transfected with plasmids containing PGR-A, PGR-B, and PGR-AB. A: RT-PCR shows an increase in PGR-to-GADPH ratios of PGR-A, PGR-B, and PGR-AB in muscle cells transfected with PGR-A, PGR-B, and PGR-AB compared with all control cells (*P < 0.02, **P < 0.01, #P < 0.001, determined by ANOVA). B: PGR-B-to-β-actin OD ratios determined by Western blot show an increase in the protein expression of PGR-B in muscle cells transfected with plasmid DNA of PGR-B or PGR-AB compared with controls or cells transfected with PGR-A (*,**P < 0.01 determined by ANOVA). Values are means ± SE; n = 3/group.

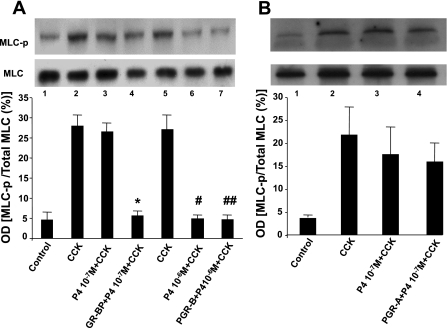

We then studied whether overexpression of PGR-B made the cells more sensitive to physiological concentrations of P4. We examined the effect of two doses of P4 on myosin phosphorylation (MLC-p) induced by CCK-8 (10−8 M). MLC-p was determined because it reflects contraction of smooth muscle cells. Pharmacological P4 concentrations (10−6 M) decreased MLC-p in response to CCK-8 in controls and in muscle cells transfected with plasmid DNA of PGR-B receptor (Fig. 4A). In contrast, physiological P4 concentrations (10−7 M) had no effect on MCL-p in control muscle cells but significantly reduced MLC-p induced by CCK-8 in cells transfected with PGR-B. Furthermore, 10−7 M P4 had no effect on MLC-p in response to CCK-8 (10−8 M) in controls or in muscle cells transfected with PGR-A, whereas 10−6 M P4 inhibited MLC-p in response to 10−8 M CCK-8 in both control and muscle cells transfected with PGR-A (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK-8, 10−8 M) stimulation of MLC phosphorylation (MLC-p) after muscle cells were treated with 2 doses of P4. A: P4 (10−6 M) inhibited MLC-p induced by CCK-8 in normal cells and muscle cells transfected with plasmid DNA of PGR-B receptor (#,##P < 0.02, determined by ANOVA.). Values are means ± SE; n = 3. P4 (10−7 M) significantly reduced MLC-p induced by CCK-8 (10−8 M) only in cells transfected with PGR-B (*P < 0.03, determined by ANOVA), but this concentration had no effect on normal muscle cells. B: 10−7 M P4 had no effect on MLC-p in response to 10−8 M CCK-8 in controls and muscle cells transfected with PGR-A. There were no significant differences by ANOVA between CCK-8 alone and 10−7 M PG + CCK-8 and PGR-A + 10−7 M P4 + CCK-8. Values are means ± SE; n = 3.

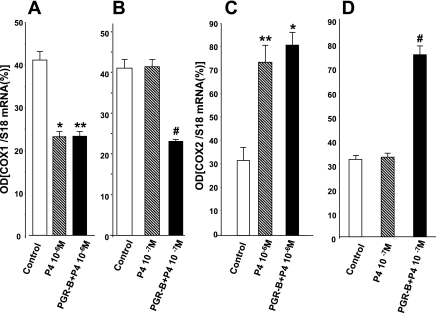

We previously showed (10) that P4 decreases COX-1 mRNA and protein expression and upregulates COX-2 mRNA and protein expression. P4 (10−6 M) significantly reduced COX-1 mRNA levels by qPCR and RT-PCR in control and muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (Fig. 5A), whereas P4 concentrations of 10−7 M reduced COX-1 mRNA only in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B but had no effect in normal cells (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, 10−6 M P4 upregulated COX-2 mRNA by qPCR in control and transfected muscle cells (Fig. 5C), whereas 10−7 M concentrations only upregulated COX-2 in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Overexpression of PGR-B increased the sensitivity of muscle cells to lower PG concentrations. A: P4 (10−6 M) significantly reduced cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 mRNA expression by qPCR in control and transfected muscle cells (*,**P < 0.001 by ANOVA). B: in contrast, P4 (10−7 M) reduced COX-1 expression only in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (#P < 0.002 by ANOVA) and not in normal cells. C: P4 (10−6 M) also significantly increased mRNA levels of COX-2 in control and muscle cells transfected with plasmid DNA of PGR-B (*,**P < 0.002). D: P4 (10−7 M) increased the mRNA levels of COX-2 (#P < 0.01 by ANOVA) but had no effect on control muscle cells. Values are means ± SE; n = 3.

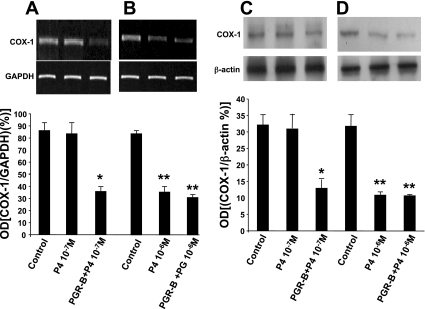

In agreement with these results, 10−6 M P4 significantly reduced COX-1 mRNA level by RT-PCR (Fig. 6A) and its protein expression by Western blot (Fig. 6C) in control and transfected muscle cells. In contrast, 10−7 M P4 reduced COX-1 mRNA level by RT-PCR (Fig. 6B) and its protein level (Fig. 6D) only in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B and had no effect in control cells.

Fig. 6.

A: P4 (10−7 M) had no effect in control muscle cells, but it downregulated COX-1 mRNA determined by RT-PCR in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (*P < 0.001 by ANOVA). B: in contrast, P4 (10−6 M) downregulated COX-1 mRNA in control and transfected muscle cells (**P < 0.01 by ANOVA). Values are means ± SE; n = 4. C: P4 (10−7 M) significantly reduced COX-1 protein levels determined by Western blot only in transfected muscle cells (*P < 0.005) and had no effect in control cells. D: P4 (10−6 M) reduced COX-1 protein levels in both muscle cells transfected with PGR-B and control muscle cells (**P < 0.001 by ANOVA). Values are means ± SE; n = 3.

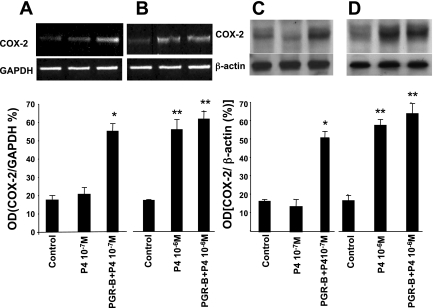

We then examined whether physiological concentrations of P4 can alter COX-2 mRNA and protein expression in control and muscle cells transfected with PGR-B. Figure 5 shows that overexpression of PGR-B increased the sensitivity of muscle cells to changes in COX enzymes induced by lower P4 concentrations. P4 (10−7 M) increased the mRNA levels of COX-2 in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B by qPCR, but once again it had no effect on control muscle cells (Fig. 5D). P4 (10−6 M) significantly increased mRNA levels of COX-2 in control as well as muscle cells transfected with plasmid DNA of PGR-B (Fig. 5C). The actions of these two different P4 concentrations were confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blot (Fig. 7). P4 (10−7 M) significantly increased COX-2 mRNA levels and protein expression only in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (Fig. 7A) and had no effect in control muscle cells (Fig. 7C). As with previous findings, 10−6M PG significantly increased COX-2 mRNA (Fig. 7B) and protein expression (Fig. 7C) in both control and muscle cells transfected with plasmid DNA of PGR-B.

Fig. 7.

Upregulation of COX-2 mRNA was demonstrated by RT-PCR, and upregulation of its protein expression was determined by Western blot. A: P4 (10−7 M) increased COX mRNA only in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (*P < 0.001 by ANOVA). B: P4 (10−6 M) increased COX mRNA levels in control and transfected muscle cells (**P < 0.005 by ANOVA). C and D: P4 concentrations of 10−7 M (C) and 10−6 M (D) had effects on protein expression of COX-2 that were consistent with mRNA level (*P < 0.005, **P < 0.001 by ANOVA). Values are means ± SE; n = 3.

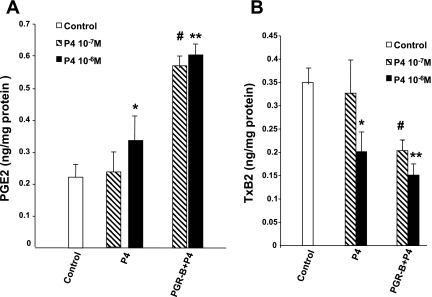

COX-2 enzymes generate PGE2, and COX-1 enzymes generate the synthesis of TxB2 (10). Therefore the functional consequences of the changes of COX enzymes induced by P4 were examined by measuring the levels of these two PGs. P4 (10−7 M) increased the production of PGE2 in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B, but it had no effect in control cells (Fig. 8A). In contrast, 10−6 M P4 increased PGE2 levels in both control cells and cells transfected with PGR-B. P4 (10−7 M) also significantly decreased TxB2 in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (Fig. 8B) but had no effect in control muscle cells. P4 (10−6 M) reduced TxB2 levels in both control cells and cells transfected with PGR-B.

Fig. 8.

Effect of 2 doses of P4 on PGE2 (A) and thromboxane (Tx)B2 (B) levels in controls and muscle cells transfected with PGR-B. P4 (10−6 M) increased PGE2 (*P < 0.05 by ANOVA) and decreased TxB2 (**P < 0.03 by ANOVA) levels in both types of muscle cells. In contrast, 10−7 M P4 induced similar changes only in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (#P < 0.01 by ANOVA). Values are means ± SE; n = 4.

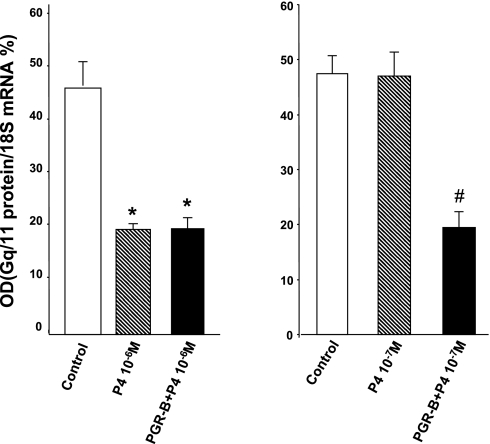

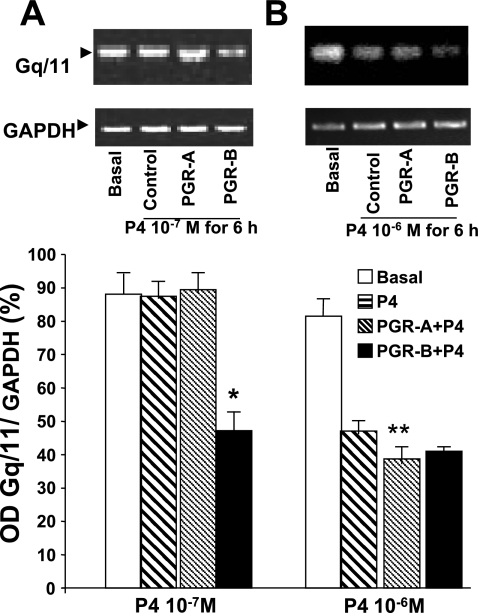

To further examine the effects of physiological concentrations of P4 in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B we determined the effect of this hormone on Gq/11 proteins. P4 impairs colonic muscle contraction induced by excitatory agonists (CCK-8, ACh) by downregulating this G protein (10). The effects of two doses of P4 on Gq/11 mRNA were determined by qPCR (Fig. 9). P4 (10−7 M) had no effect on Gq/11 mRNA in control muscle cells or in cells transfected with PGR-A but downregulated Gq/11 in cells transfected with PGR-B. In contrast, 10−6 M P4 reduced Gq/11 mRNA levels in control and muscle cells transfected with plasmid DNA of PGR-B.

Fig. 9.

Effect of 2 doses of P4 on Gq/11 protein mRNA in controls and muscle cells transfected with PGR-B determined by qPCR. A: P4 (10−6 M) downregulated the levels of Gq/11 in control and transfected muscle cells (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA). B: P4 (10−7 M) downregulated Gq/11 only in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (#P < 0.01). Values are means ± SE; n = 3.

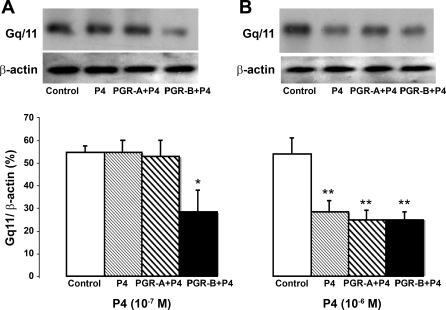

Moreover, 10−7 M P4 reduced Gq/11 mRNA by RT-PCR in muscle transfected with PGR-B but had no effect on control muscle cells or cells transfected with PGR-A (Fig. 10A). In contrast, 10−6 M P4 lowered the Gq/11 mRNA levels in control cells and muscle cells transfected with PGR-A and PGR-B (Fig. 10B). Consistent with these findings, 10−7 M P4 had no effect on Gq/11 protein expression by Western blot in control muscle cells but decreased this protein level in muscle cells transfected with plasmid DNA of PGR-B (Fig. 11A). In contrast, 10−6 M P4 lowered the levels of Gq/11 protein in control cells and muscle cells transfected with plasmid DNA of PGR-B and PGR-A (Fig. 11B).

Fig. 10.

Effect of P4 on Gq/11 mRNA levels determined by RT-PCR. B: 10−6 M P4 decreased mRNA levels in controls and muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (**P < 0.01 by ANOVA). A: in contrast, 10−7 M P4 reduced mRNA levels only in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA). Values are means ± SE; n = 3.

Fig. 11.

P4 effects on Gq/11 protein levels determined by Western blot analysis. B: 10−6 M P4 decreased Gq/11 levels in controls and muscle cells transfected with PGR-A or PGR-B DNA (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA). A: in contrast, 10−7 M P4 reduced protein levels only in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B (**P < 0.003 by ANOVA). Values are means ± SE; n = 3.

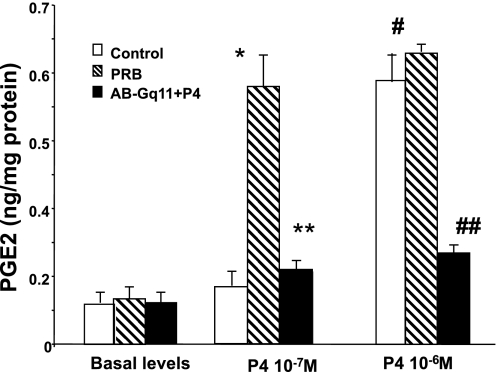

To examine the role of Gq/11 in the upregulation of COX-2 and increases in PGE2 levels induced by P4 we determined the effects of this hormone on the levels of PGE2 in permeable muscle cells pretreated with a Gq/11 antibody for 1 h before exposure to two concentrations of P4 for 6 h. Gq/11 antibody blocked the increase in PGE2 levels induced by PG concentrations of 10−7 and 10−6 M in permeable control and transfected muscle cells (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

PGE2 levels in control and muscle cells transfected with PGR-B DNA. Both P4 concentrations of 10−7 and 10−6 M caused an increase in the levels of PGE2 in muscle cells transfected with PGR-B compared with control muscle cells (*,#P < 0.004 by ANOVA). Gq/11 protein antibody (1:400 titer) blocked the increase in PGE2 induced by both P4 concentrations in these transfected cells (**,##P < 0.005 by ANOVA). Values are means ± SE; n = 3.

DISCUSSION

The present studies show that normal muscle cells from the circular layer of the colon were successfully transfected with plasmids containing the DNA of PGR-A, -B, or -AB in tissue culture, with the muscle cells maintaining their phenotypic features. These studies focused on the effect of transfection of PGR-B on myosin phosphorylation induced by CCK-8 and on P4-induced changes in the signal transduction of normal colon muscle cells. Our findings suggest that P4 acting on PGR-B downregulates Gq/11 proteins and impairs muscle contraction by excitatory agonists that act on G protein-coupled receptors. Excitatory agonists, such as CCK-8, ACh, and others, are known to act on receptors that couple to Gq/11 proteins to activate the signal transduction that mediates the contraction of colonic muscle cells (43). These findings are consistent with previous observations that PGR-A and PGR-B mediate different actions induced by P4 (15, 27).

The transfection of P4 receptors was demonstrated by increases in mRNA and protein expression of receptors A and B. Overexpression of PGR-B made normal colon muscle cells more sensitive to physiological concentrations of P4 than control muscle cells transfected with empty vector or treated with tissue culture medium alone. The cells that overexpressed the PGR-B responded to P4 concentrations of 10−7 M that had no effect on control muscle cells. Normal colonic muscle cells respond to pharmacological P4 concentrations of 10−6 M or higher. P4 concentrations of 10−7 M impaired myosin phosphorylation induced by CCK-8, downregulated COX-1 and Gq/11 mRNA, and decreased their protein expression in cells with overexpressed PGR-B. Myosin phosphorylation, the biochemical expression of muscle contraction, was examined because cultured smooth muscle cells adhere to the slides and cannot contract after stimulation. Smooth muscle contraction is regulated by phosphorylation of the 20-kDa MLCs (20). Therefore the impairment of myosin phosphorylation induced by CCK-8 indicates the reduced contractility of muscle cells treated with P4. P4 (10−7 M) was also able to downregulate COX-1 and lower TxB2 levels and Gq/11 proteins. It also upregulated COX-2 mRNA and protein expression. Consistent with these findings, 10−7 M P4 also increased PGE2 levels in these transfected muscle cells with PGR-B overexpression. This PG concentration, however, had no effect in control muscle cells. In contrast, 10−6 M P4 was able to reduce myosin phosphorylation induced by CCK-8 and altered those signal transduction steps in control and muscle cells transfected with PGR-B.

The finding that P4 caused an increase in the mRNA and protein expression of COX-2 and increases in PGE2 levels in muscle cells with an overexpression of PGR-B was unexpected. PGE2 relaxes circular muscle cells from the colon, suggesting that stimulation of Gq/11 proteins might have an inhibitory effect on COX-2 expression and PGE2 generation (10). This hypothesis was confirmed by examining the effect of P4 on muscle cells pretreated with Gq/11 antibody. Pretreatment with this antibody blocked the effect of P4 on the expected increase in PGE2 levels. Moreover, although PGE2 may modulate gastrointestinal motility as a paracrine factor, particularly in inflammatory processes, PGs also have important autocrine functions as we (10) and others have demonstrated. As autocrine factors they contribute to cytoprotection, cell proliferation, and the genesis of myogenic tonic and phasic contractions.

These results are in agreement with previous findings that colon muscle cells from normal women do not respond to physiological serum P4 levels that fluctuate around 10−7 M during the menstrual cycle unless the cells have increased levels of P4 receptors as reported in women with STC. These findings may also explain the conflicting reports regarding the correlation of bowel patterns and gastrointestinal transit time during the menstrual cycle. These studies, however, do not rule out the possibility that abnormal levels of other factors such as chaperones (heat shock proteins) or promoters may increase the responsiveness of P4 receptors to the hormone.

In summary, the present data demonstrate that overexpression of PGR-B causes increased sensitization of normal colonic muscle cells that respond to P4 concentrations that do not normally affect colonic muscle cells. These findings also support the hypothesis that has been previously advanced that in female patients with STC the impaired basal and agonist-induced colonic contractions and alterations in G proteins, COX enzymes, and PGs are due to an overexpression of P4 receptors in colon muscle cells that respond to normal circulating levels of P4 in nonpregnant women and during pregnancy. These data also suggest that physiological concentrations of P4 are unlikely to influence the functions of colon muscle cells with normal expression of P4 receptors.

GRANTS

These studies were supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant RO1-5-DK-61416.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aytug N, Imeryuz A, Enc N, Bekiroglu FY, Aktas N, Ulusoy G. Gender influence on jejunal migrating motor complex. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G255–G263, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron TH, Ramirez B, Richter JE. Gastrointestinal motility disorders during pregnancy. Ann Intern Med 118: 366–375, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharucha AE, Phillips S. Slow transit constipation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 30: 77–95, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björnsson B, Theodors A, Kjeld M. The relationship of gastrointestinal symptoms and menstrual cycle phase in young healthy women. Laeknabladid 92: 677–682, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonapace ES, Fisher R. Constipation and diarrhea in pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 27: 197–211, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brittingham J, Phiel C, Trzyna WC, Gabbeta V, McHugh KM. Identification of distinct molecular phenotypes in cultured gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology 115: 605–617, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabral R, Gutierrez M, Fernandez AI, Cantabrana B, Hidalgo A. Progesterone and pregnanolone derivatives relaxing effect on smooth muscle. Gen Pharmacol 25: 173–178, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Q, Xiao ZL, Biancani P, Behar J. Downregulation of Galphaq-11 protein expression in guinea pig antral and colonic circular muscle during pregnancy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G895–G900, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng L, Harnett K, Cao W, Liu F, Behar J, Fiocchi C, Biancani P. Hydrogen peroxide reduces lower esophageal sphincter tone in human esophagitis. Gastroenterology 129: 1675–1685, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cong P, Pricolo V, Biancani P, Behar J. Abnormalities of prostaglandins and COX enzymes in female patients with slow transit constipation. Gastroenterology 133: 445–453, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corker CS, Michie E, Hobson B, Parboosingh J. Hormonal patterns in conceptual cycles and early pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 83: 489–494, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Monte SM, Tamaki S, Cantarini MC, Ince N, Wiedmann M, Carter JJ, Lahousse SA, Califano S, Maeda T, Ueno T, D'Errico A, Trevisani F, Wands JR. Aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-beta-hydroxylase regulates hepatocellular carcinoma invasiveness. J Hepatol 44: 971–983, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derbyshire EJ, Davies J, Costarelli V, Detmar P. Changes in bowel function: pregnancy and the puerperium. Dig Dis Sci 52: 324–328, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everson G Gastrointestinal motility in pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 21: 751–776, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goswami A, Biancani P, Behar J. Roles of progesterone (PG) receptors A and B on relaxation and contraction of muscle cells from human and guinea pig colon. Gastroenterology 130: A224, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagger R, Kumar D, Benson M, Grundy A. Colonic motor activity in slow-transit idiopathic constipation as identified by 24-h pancolonic ambulatory manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil 15: 515–522, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halayko AJ, Salari H, Ma X, Stephens NL. Markers of airway smooth muscle cell phenotype. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 270: L1040–L1051, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedges JC, Oxhorn BC, Carty M, Adam LP, Yamboliev IA, Gerthoffer WT. Phosphorylation of caldesmon by ERK MAP kinases in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278: C718–C726, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H. Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques. J Histochem Cytochem 29: 577–580, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ihara E, MacDonald J. The regulation of smooth muscle contractility by zipper-interacting protein kinase. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 85: 79–87, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamm MA, Farthing MJ, Lennard-Jones JE, Perry LA, Chard T. Steroid hormone abnormalities in women with severe idiopathic constipation. Gut 32: 80–84, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knowles CH, Martin JE. Slow transit constipation: a model of human gut dysmotility: review of possible etiology. Neurogastroenterol Motil 12: 181–196, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuemmerle J IGF-I elicits growth of human intestinal smooth muscle cells by activation of PI3K, PDK-1, and p70S6 kinase. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284: G411–G422, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuemmerle J, Bushman TL. IGF-I stimulates intestinal muscle cell growth by activating distinct PI 3-kinase and MAP kinase pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 275: G151–G158, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahousse SA, Carter JJ, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Differential growth factor regulation of aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-beta-hydroxylase family genes in SH-Sy5y human neuroblastoma cells. BMC Cell Biol 7: 41, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawson M, Kern F, Everson GT. Gastrointestinal transit time in human pregnancy. Prolongation in the 2nd and 3rd trimester followed by postpartum normalization. Gastroenterology 89: 996–999, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leo C, Li H, Chen JD. Differential mechanisms of nuclear receptor regulation by receptor-associated coactivator 3. J Biol Chem 275: 5976–5982, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy N, Lemberg E, Sharf M. Bowel habit in pregnancy. Digestion 4: 216–222, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy N, Lemberg E, Steiner Z, Epstein L, Tamir A. Bowel habits in Israel. A cohort study. J Clin Gastroenterol 16: 295–299, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma FH, Higashira H, Ukai Y, Hanai T, Kiwamoto H, Park YC, Kurita T. A new enzymic method for the isolation and culture of human bladder body smooth muscle cells. Neurourol Urodyn 21: 71–79, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miura M, Hata Y, Hirayama K, Kita T, Noda Y, Fujisawa K, Shimokawa H, Ishibashi T. Critical role of the Rho-kinase pathway in TGF-beta2-dependent collagen gel contraction by retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res 82: 849–859, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakayama H, Enzan H, Yamamoto M, Miyazaki E, Yasui W. High molecular weight caldesmon positive stromal cells in the capsule of hepatocellular carcinomas. J Clin Pathol 57: 776–777, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkman HP, Wang MB, Ryan JP. Decreased electromechanical activity of guinea pig circular muscle during pregnancy. Gastroenterology 105: 1306–1312, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porter RM, Holmes TC, Newman EL, Hopwood D, Wilkinson JM, Cuschieri A. Monoclonal antibodies to cytoskeletal protein: an immunohistochemical investigation of human colon cancer. J Pathol 170: 435–440, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preston DM, Lennard-Jones J. Severe chronic constipation of young women: “idiopathic slow transit constipation.” Gut 27: 41–48, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rees WD, Rhodes J. Altered bowel habit and menstruation. Lancet 1: 475, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rush DS, Tan J, Baergen RN, Soslow RA. h-Caldesmon, a novel smooth muscle specific antibody, distinguishes between cellular leomyoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 25: 253–258, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shukla AR, Nguyen T, Zheng Y, Zderic SA, diSanto M, Wein AJ, Chacko S. Overexpression of smooth muscle specific caldesmon by transfection and intermittent agonist induced contraction alters cellular morphology and restores differentiated smooth muscle phenotype. J Urol 171: 1949–1954, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turnbull GK, Thompson D, Day S, Martin J, Walker E, Lennard-Jones JE. Relationship between symptoms, menstrual cycle and oro-caecal transit in normal and constipated women. Gut 30: 30–34, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wald A, Van Thiel DH, Hoechstetter L, Gavaler JS, Egler KM, Verm R, Scott L, Lester R. Gastrointestinal transit: the effect of the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology 80: 1497–1500, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldron D, Bowes KL, Kingma YJ, Cote KR. Colonic and anorectal motility in young women with severe idiopathic constipation. Gastroenterology 95: 1388–1394, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward A, Van Thiel D, Hoechstetter L, Gavaler JS, Egler KM, Verm R, Scott L, Lester R. Effect of pregnancy on gastrointestinal transit. Dig Dis Sci 27: 1015–1018, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao ZL, Pricolo V, Biancani P, Behar J. Role of progesterone signaling in the regulation of G-protein levels in female chronic constipation. Gastroenterology 128 667–675, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]