Abstract

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), an incretin, which is used to treat diabetes mellitus in humans, inhibited vagal activity and activated nitrergic pathways. In rats, GLP-1 also increased sympathetic activity, heart rate, and blood pressure (BP). However, the effects of GLP-1 on sympathetic activity in humans are unknown. Our aims were to assess the effects of a GLP-1 agonist with or without α2-adrenergic or -nitrergic blockade on autonomic nervous functions in humans. In this double-blind study, 48 healthy volunteers were randomized to GLP-1-(7-36) amide, the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate (l-NMMA), the α2-adrenergic antagonist yohimbine, or placebo (i.e., saline), alone or in combination. Hemodynamic parameters, plasma catecholamines, and cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation were measured by spectral analysis of heart rate. Thereafter, the effects of GLP-1-(7-36) amide on muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) were assessed by microneurography in seven subjects. GLP-1 increased (P = 0.02) MSNA but did not affect cardiac sympathetic or parasympathetic indices, as assessed by spectral analysis. Yohimbine increased plasma catecholamines and the low-frequency (LF) component of heart rate power spectrum, suggesting increased cardiac sympathetic activity. l-NMMA increased the BP and reduced the heart rate but did not affect the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. GLP-1 increases skeletal muscle sympathetic nerve activity but does not appear to affect cardiac sympathetic or parasympathetic activity in humans.

Keywords: nitric oxide, adrenergic, catecholamines, spectral analysis, heart rate

glucagon-like peptide-1 (glp-1) is an incretin produced by enteroendocrine L cells in the small intestine. Under hyperglycemic conditions, GLP-1 regulates blood glucose by reducing glucagon secretion and increasing insulin secretion by the pancreas, and by delaying gastric emptying by vagal inhibition. Unlike the native peptides [i.e., GLP-1-(7-36) amide and GLP-1-(9-36) amide], the GLP-1 receptor agonist exendin-4 is resistant to inactivation by dipeptidyl peptidase IV and is used as an adjunct to oral hypoglycemic therapy in type II diabetes mellitus (DM).

GLP-1 is also synthesized by neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract, and GLP-1 receptors are also found in the heart and in areas of the central nervous system that govern autonomic control (25, 49). Peripheral and central GLP-1 agonists induce c-fos expression, suggesting they activate the adrenal medulla and autonomic regulatory neurons in the rat brain (53). GLP-1 receptor agonists have dose-dependent chronotropic and pressor responses in rodents (5, 53), and GLP-1 agonists improve cardiac output and blood pressure (BP) in dogs with pacing-induced cardiomyopathy (28). While GLP-1 did not increase BP in monkeys (55) or during continuous subcutaneous infusion for 6 wk in humans (56), it has beneficial effects on left ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction (29) and on vasodilatation in healthy subjects and patients with type II DM and stable coronary disease (6, 32). GLP-1 has also been implicated to cause tachycardia in patients who have rapid gastric emptying after gastric resection (i.e., postgastrectomy dumping syndrome), because these patients have increased heart rate, plasma GLP-1, and plasma norepinephrine concentrations after an oral glucose challenge (54). However, the effects of GLP-1 on muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) and cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic regulation in humans have not been studied. These questions are important because diabetic autonomic neuropathy is associated with significant increases in morbidity and mortality, including an increased risk of sudden death (37, 42, 43).

The aims of this study were to assess the effects of GLP-1, either alone or in combination with the α2-adrenergic antagonist yohimbine, or the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate (l-NMMA) on the hemodynamic parameters, cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic tone, as assessed by time frequency distribution of heart rate and BP, and plasma catecholamines in humans. Because nitric oxide (NO) mediates some effects of GLP-1 (e.g., inhibition of small bowel motility in rats) (48)—protection against ethanol-induced gastric mucosal lesions (20) and relaxation of vascular endothelium (31)]—and because NO also augments cardiac vagal control in humans (10), we also evaluated the NOS inhibitor l-NMMA, alone and in combination with GLP-1 in these studies. Yohimbine and placebo were used as positive and negative controls of cardiac sympathetic activity, respectively. After noting that GLP-1 did not significantly affect cardiac autonomic functions as assessed by spectral analysis, we subsequently assessed the effects of GLP-1 on skeletal muscle vasoconstrictor nerve activity measured by microneurography.

METHODS

Overall Experimental Design

This report incorporates observations on autonomic parameters from two studies. Experiment 1 was designed to assess whether nitrergic and/or α2-adrenergic mechanisms mediate the effects of GLP-1, which is released in response to oral nutrient infusion, on postprandial gastric accommodation. Data on gastric effects, but not autonomic parameters (i.e., hemodynamic effects, spectral analysis of heart rate and BP), have been presented elsewhere (1, 2). Therefore, these studies evaluated the effects of GLP-1 alone or in combination with the NOS inhibitor l-NMMA or the α2-adrenoreceptor antagonist yohimbine on autonomic and hemodynamic parameters under fasting and postprandial conditions. Subsequently, the effects of GLP-1 on skeletal muscle vasoconstrictor activity measured by microneurography were evaluated in experiment 2.

Subjects

Fifty-five healthy volunteers, aged 18–54 years (mean age, 31 yr; 42 women) were recruited by public advertisement. None had significant underlying illnesses or medication use, except for oral contraceptives. Functional GI disorders, anxiety, and depression were excluded by validated screening questionnaires (46), a clinical interview, and a physical examination. Diabetes mellitus was excluded by checking the fasting serum glucose. The studies were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Initially, 48 subjects (mean age, 31 yr; 36 women) were studied in experiment 1. Subsequently, seven subjects (mean age, 26 yr; 6 women) were studied in experiment 2.

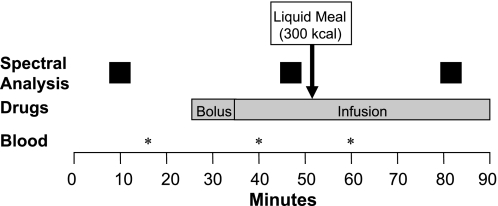

Experimental Design for Experiment 1

These studies were conducted after an overnight fast. Two peripheral venous cannulas inserted for drug infusion and a separate peripheral venous cannula inserted used for blood sampling. All studies took place in the morning. Subjects were then placed in the supine position in a quiet room with lights dimmed. At least 30 min was allowed between cannula insertion and study commencement. To simulate meal-stimulated GLP-1 release, these studies were conducted under fasting and postprandial conditions. Heart rate, BP, and plasma catecholamines were studied during baseline and during intravenous infusion of placebo or drugs, both before and after a 300-kcal liquid meal (Ensure, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL; 1 kcal/ml) (Fig. 1). Drugs were given as a 10-min bolus followed by a continuous infusion lasting for the remainder of the study. Subjects were randomized, in a double-blind manner, to one of six arms: placebo, GLP-1, the NOS inhibitor l-NMMA, the α2-adrenoreceptor antagonist yohimbine, GLP-1 combined with l-NMMA (i.e., GLP-1/l-NMMA), or GLP-1 combined with yohimbine (i.e., GLP-1/yohimbine). This randomization was balanced on sex and body mass index (BMI) (i.e., ≤25 vs. >25 kg/m2). Because of this stratification, the number of subjects randomized to each group was similar but not identical. As control or placebo, we administered 15 ml of 0.9% saline as a “bolus” followed by an infusion at 42.9 ml/h for the entire study. When only one drug was administered, saline was administered through the 2nd intravenous cannula.

Fig. 1.

Design for experiments 1 and 2. Hemodynamic parameters, spectral analysis of heart rate and blood pressure, and plasma catecholamines were assessed as shown.

Drugs

GLP-1, l-NMMA, and yohimbine were used under investigator-initiated Investigational New Drug approvals from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. All infusions were prepared by standard practice in the Mayo General Clinical Research Center Research Pharmacy using current American Society of Health-System Pharmacists class III procedures for sterile preparation.

Glucagon-like peptide-1.

GLP-1 (7-36 amide) (Bachem, San Diego, CA) was infused at 2.4 pmol·kg−1·min−1 for 10 min followed by 1.2 pmol·kg−1·min−1 for the remainder of the study. This dosing regimen produced supraphysiological plasma levels and normalized blood glucose concentrations in type II DM (23). In healthy subjects, this dose inhibited antro-duodenal contractility, increased pyloric tone, and also increased fasting gastric volumes (1, 40).

NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate.

In experiment 1, NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate (l-NMMA) (Clinalfa AG, Läufelfingen, Switzerland), a NOS inhibitor, was infused at 4 mg·kg−1·h−1. In healthy subjects, this dose stimulated small intestinal motility (38) and reduced postprandial accommodation (45). In a previous study, a lower dose (i.e., 3 mg·kg−1·h−1) increased BP and induced bradycardia (10).

Yohimbine.

Yohimbine HCl (Spectrum Chemical, Gardena, CA) was administered as a bolus (i.e., 0.125 mg/kg over 10 min) followed by an infusion (i.e., 0.06 mg·kg−1·h−1). This dose is safe for administration to healthy subjects, elicited a two- to three-fold increase in plasma norepinephrine levels, and stimulated colonic motility in humans (7, 14).

Plasma catecholamines.

A 10-ml venous blood sample was drawn before and after drug infusion during fasting conditions and at 10 min after a meal (Fig. 1). Blood samples were collected in chilled glass tubes containing 0.05 ml of 10% sodium metabisulfite for catecholamines. Plasma was obtained by refrigerated centrifugation and fast-frozen in dry ice and acetone before storage at −70°C until assayed. Catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine) were extracted from plasma (12) and subjected to HPLC with electrochemical detection (18). About 70% of norepinephrine released by sympathetic nerves is recaptured and then recycled into vesicles. Norepinephrine leaking from storage granules or norepinephrine recaptured after release by sympathetic nerves is deaminated to plasma dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG), which is almost completely derived from metabolism of neuronal norepinephrine (11). Therefore, plasma norepinephrine measurements were complemented by measuring plasma DHPG.

Hemodynamic Monitoring and Spectral Analysis of Heart Rate and Blood Pressure

Continuous beat-to-beat photoplethysmographic BP recordings (Finapres BP monitor 2300 and Finometer, Ohmeda; Englewood, CO) and cardiac rhythm using a three-lead ECG (Ivy Biomedical Systems, Branford, CT) were digitally recorded. Using customized software, the digitized unfiltered ECG and arterial pressure waveforms were analyzed for 5-min segments before and after drug administration under fasting conditions and for 5 min at 15 min after a 300-kcal meal. An in-house established procedure was used to inspect the ECG and BP signals for artifact. Data acquisition and analyses were consistent with established standards (3, 36). The R-wave peaks and BP peaks were detected by an established peak-detection algorithm. For power spectral analysis, a time series of R-R intervals and systolic BP at each R-R interval during the 5-min periods were linearly interpolated and resampled at 4 Hz followed by fast Fourier transform, as previously described after standardized outlier removal using Mayo in-house analysis software (BMDV32, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, NY). High resolution was achieved by independent time and frequency smoothing (30).

For heart rate variability (HRV), power was calculated in the low frequency (LF; 0.03–0.14 Hz) and in high frequency (HF; 0.14–0.30 Hz) components. HF power of R-R variability (HRVHF) is a measure of cardiac parasympathetic activity (34). The LF component of R-R variability (HRVLF) primarily responds to variations in cardiac sympathetic activity (3, 33). Sympathetic modulation of BP variability was also assessed by analyzing power in the LF component (0.03–0.14 Hz, SBPLF) for beat-to-beat systolic BP. The LF-to-HF power ratio of R-R variability (LFR-R/HFR-R) is a representative index of sympathetic to parasympathetic balance in physiological and pathophysiological conditions (3, 26, 33).

Experimental Design and Procedure in Experiment 2

In this study, MSNA was directly measured by peroneal nerve microneurography for 10 min before and 60 min after GLP-1, administered at the same dose as in experiment 1. Burst activity in sympathetic nerves could be recorded in 7 of 9 healthy volunteers who were recruited for this part of the study. Cardiac rhythm and BP were also monitored by ECG and Finapres sphygmomanometry (Ohmeda, Madison, WI), respectively.

Studies were performed in a temperature-controlled room (23°C) with subjects in the supine position. An intravenous cannula was placed in an antecubital vein a minimum of 45 min before baseline recordings. Upon arrival in the laboratory, subjects were instrumented for recording of ECG, arterial pressure, respiration, and MSNA. Finapres monitor readings were verified with manual sphygmomanometry to ensure accuracy. After instrumentation, 10 min of baseline data were recorded.

Efferent multiunit, postganglionic MSNA was measured directly using standard microneurographic techniques, as previously described (44). Briefly, two sterile tungsten microelectrodes (tip diameter, 5–10 μm; Frederick Haer; Bowdoinham, ME) were inserted, one into the peroneal nerve for recording of MSNA and the other ∼3 cm away (not in a nerve) to serve as a reference. A signal processing system (662C-3 Nerve Traffic Analysis System; University of Iowa Bioengineering, Iowa City, IA) amplified (8 × 104 times), band-pass filtered (700–2,000 Hz), rectified, and integrated (time constant, 0.1 s) the nerve signal.

MSNA was quantified as burst frequency (bursts/min). Sympathetic bursts in the integrated neurogram were identified by a custom-manufactured analysis program (8, 9); burst identification was then corrected by visual inspection by a single investigator. MSNA data were averaged over 4 min at the end of the baseline period and over 4 min at the end of the GLP-1 period.

Statistical Analysis

Consistent with the experimental design, the statistical analysis was designed to assess the effects of GLP-1 with or without l-NMMA and GLP-1 with or without yohimbine on summary parameters during the fasting postdrug and postprandial postdrug periods. Overall treatment effects were assessed by analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) using sex, BMI, and the corresponding fasting predrug values as covariates. Thereafter, appropriate pairwise comparisons were also analyzed, that is, between individual agents (i.e., GLP-1 and separately l-NMMA vs. placebo) and between the combination (i.e., GLP-1 + l-NMMA) vs. GLP-1 alone were assessed. Similar comparisons were performed for the GLP-1 + yohimbine data. Pairwise comparisons were only considered significant if overall treatment effects were also significant. Because this was an intent-to-treat analysis, missing data were imputted using the corresponding mean value over all nonmissing data values. The error degrees of freedom in the respective ANCOVA models were decreased by one for each missing value imputted for a given response parameter. The data presented in the text, tables, and figures are the “raw” means ± SE, unadjusted for covariates and do not include any imputted values. In experiment 2, the effects of GLP-1 on MSNA and hemodynamic parameters were assessed by a signed rank test using the seven subjects with available data.

RESULTS

None of the subjects experienced significant adverse events during these studies. At baseline, there were no clinically important differences in age, sex, BMI, fasting serum glucose, plasma norepinephrine, or plasma DHPG among groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Variable |

Experiment 1 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | GLP-1 | Yohimbine | GLP-1 + Yohimbine | l-NMMA | GLP-1 + l-NMMA | |

| n | 8 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 9 |

| Age, yr | 34±5 | 34±3 | 37±3 | 29±3 | 33±4 | 28±3 |

| Sex, % female | 75 | 86 | 57 | 70 | 86 | 67 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26±2 | 27±2 | 26±2 | 27±2 | 27±2 | 27±1 |

| Serum glucose, mg/dl | 87±2 | 88±2 | 88±2 | 89±2 | 90±5 | 88±2 |

| NE level, pg/ml | 214±31 | 177±33 | 266±77 | 176±35 | 167±17 | 171±25 |

| DHPG level, pg/ml | 1578±266 | 1514±206 | 1732±168 | 1430±79 | 1857±128 | 1830±231 |

All values except sex are actual means ± SE. BMI, body mass index; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide; L-NMMA, NG-monomethyl-L-arginine acetate; NE, norepinephrine; DHPG, dihydroxyphenylglycol.

Effects of GLP-1 and l-NMMA on Cardiovascular Parameters

GLP-1 did not significantly affect heart rate or BP compared with placebo during the fasting or postprandial periods in experiment 1 (Table 2). Although GLP-1 increased systolic (P < 0.05, signed rank test) and diastolic BP (P = 0.06) during experiment 2, these effects were rather modest. GLP-1 did not significantly increase the heart rate during experiment 2. During the fasting period, l-NMMA had overall treatment effects (P < 0.01) on diastolic BP and heart rate. l-NMMA alone, and in combination with GLP-1, increased (P ≤ 0.02) the diastolic BP and reduced (P ≤ 0.02) the heart rate, compared with placebo and GLP-1, respectively. During the postprandial period, GLP-1/l-NMMA increased the diastolic BP compared with GLP-1 alone (P < 0.04 for overall treatment effect, P < 0.05 for pairwise comparison). During the postprandial period, l-NMMA reduced the heart rate compared with placebo (P < 0.01 for overall treatment effect, P < 0.01 for pairwise comparison). Moreover, GLP-1 and l-NMMA reduced the heart rate compared with GLP-1 alone (P < 0.01 for overall treatment effect, P < 0.01 for pairwise comparison).

Table 2.

Effect of drugs on blood pressure and heart rate

| Group | Baseline |

Postdrug |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting | Postprandial | |||||

| Experiment 1 | ||||||

| Placebo (n = 8) | ||||||

| SBP | 122±6 | 121±7 | 123±9 | |||

| DBP | 66±3 | 64±4 | 63±5 | |||

| HR | 64±7 | 67±4 | 71±3 | |||

| GLP-1 (n = 7) | ||||||

| SBP | 120±6 | 122±5 | 130±9 | |||

| DBP | 63±5 | 64±3 | 66±7 | |||

| HR | 65±3 | 68±3 | 69±2 | |||

| Yohimbine (n = 7) | ||||||

| SBP | 119±7 | 126±9 | 114±11 | |||

| DBP | 68±6 | 76±7 | 74±9 | |||

| HR | 61±3 | 64±3 | 66±4 | |||

| GLP-1 + Yohimbine (n = 10) | ||||||

| SBP | 125±7 | 135±9 | 127±2 | |||

| DBP | 69±4 | 73±6 | 76±3 | |||

| HR | 63±3 | 64±3 | 69±3 | |||

| l-NMMA (n = 7) | ||||||

| SBP | 125±8 | 132±8 | 119±8 | |||

| DBP | 68±3 | 76±6* | 70±5 | |||

| HR | 66±6 | 57±2* | 61±3* | |||

| GLP-1 + L-NMMA (n = 9) | ||||||

| SBP | 116±5 | 127±6 | 129±6 | |||

| DBP | 61±5 | 73±5† | 75±4† | |||

| HR | 59±3 | 56±3† | 57±3† | |||

| Experiment 2 | ||||||

| GLP-1 (n = 7) | ||||||

| SBP | 138±8 | 145±9‡ | NA | |||

| DBP | 74±6 | 77±6 | NA | |||

| HR | 67±5 | 70±4 | NA | |||

All values are actual means ± SE in mmHg. SBP, systolic blood pressure, given in mmHg; DBP, diastolic blood pressure, given in mmHg; HR, heart rate, given in beats per minute, bpm. NA, not available.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. placebo.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. GLP-1 alone.

0.02 < P ≤ 0.05, pre vs. post (signed rank test).

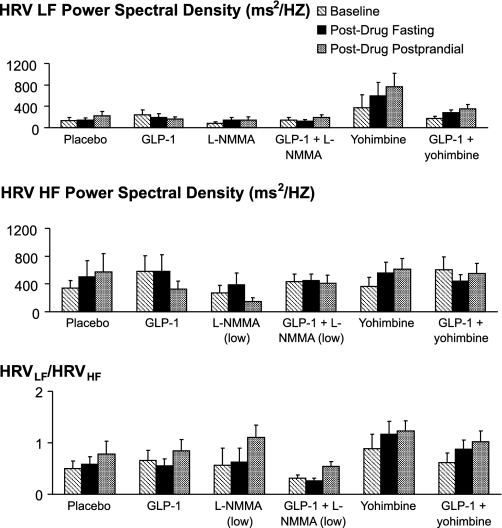

Neither GLP-1 nor l-NMMA alone or in combination had significant effects on HRV (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of drugs on heart rate variability [i.e., normalized low-frequency power of heart rate variability (HRVLF, top), HRVLF/HRVHF (middle)], and normalized high-frequency power of heart rate variability (HRVHF, bottom), during fasting and postprandial periods. All values are actual means ± SE. l-NMMA, NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. placebo. †P ≤ 0.05 vs. GLP-1 alone.

Effects of Yohimbine on Cardiovascular Parameters

Yohimbine did not significantly affect heart rate or BP compared with placebo during the fasting or postprandial periods. However, yohimbine had significant and mostly similar effects on HRV during fasting and postprandial periods. Thus, yohimbine increased power in the HRVLF component (P < 0.05 for overall treatment effects, P < 0.05 vs. placebo), suggestive of increased cardiac sympathetic activity (Fig. 2). Similarly, power in the HRVLF component was higher (P < 0.05) for GLP-1 and yohimbine compared with GLP-1 alone. During the fasting period, yohimbine also increased power in SBPLF, which is also a measure of cardiac sympathetic activity (P = 0.057 for overall treatment effect, P < 0.01 vs. placebo) (Table 3). In contrast to the HRVLF component, these medications did not have significant effects on HRVHF or the HRVLF/HRVHF ratio.

Table 3.

Effect of drugs on variability in systolic blood pressure

| Group |

Variability in Low-Frequency Component of Systolic BP |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Postdrug Fasting | Postdrug Postprandial | |

| Placebo (n = 8) | 0.93±0.28 | 1.36±0.25 | 1.53±0.36 |

| GLP-1 (n = 7) | 1.67±0.73 | 2.01±0.64 | 1.34±0.54 |

| l-NMMA (n = 7) | 0.78±0.33 | 1.07±0.69 | 1.90±0.67 |

| GLP-1 + l-NMMA (n = 9) | 1.36±0.64 | 1.65±0.58 | 0.94±0.39 |

| Yohimbine (n = 7) | 0.80±0.31 | 2.38±0.44* | 3.21±1.28 |

| GLP-1 + yohimbine (n = 10) | 1.05±0.26 | 2.10±0.55 | 2.07±0.45 |

All values are actual means ± SE.

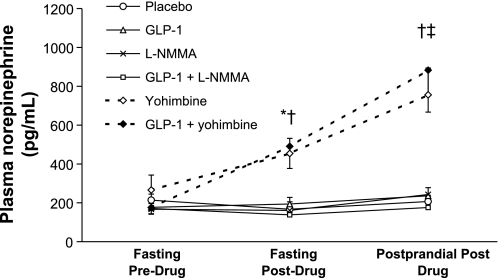

Effects of GLP-1, l-NMMA, and Yohimbine on Plasma Catecholamines

l-NMMA did not significantly affect fasting plasma norepinephrine concentrations (Fig. 3). Yohimbine had overall treatment effects (P = 0.02) on fasting plasma norepinephrine concentrations; pairwise comparisons revealed that plasma norepinephrine was higher for yohimbine than placebo (P = 0.06) and for GLP-1 and yohimbine than GLP-1 alone (P = 0.01) (Fig. 3). Yohimbine also increased postprandial plasma norepinephrine concentrations (P = 0.003 for overall treatment effects). Pairwise comparisons demonstrated higher plasma norepinephrine concentrations for yohimbine compared with placebo (P ≤ 0.04) and for GLP-1/yohimbine compared with GLP-1 alone (P < 0.005). In contrast, fasting norepinephrine concentrations were lower (P = 0.02) for GLP-1/l-NMMA compared with GLP-1 alone.

Fig. 3.

Effect of drugs on plasma norepinephrine. During the fasting and both postprandial phases, plasma norepinephrine levels were higher among subjects who received yohimbine alone or in combination with GLP-1. *P = 0.06 yohimbine vs. placebo. †P = 0.01 GLP-1 and yohimbine vs. GLP-1 alone. ‡P < 0.05 yohimbine vs. placebo.

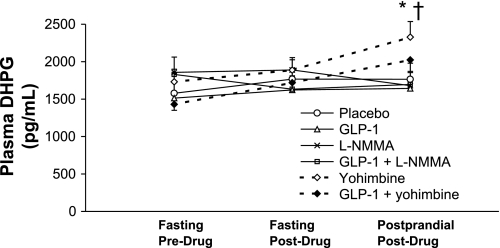

Drug effects on fasting DHPG levels were not significant (Fig. 4). However, yohimbine increased postprandial DHPG levels compared with placebo, and GLP-1/yohimbine increased postprandial DHPG levels compared with GLP-1 alone (P < 0.03 for overall treatment effect, P < 0.03 for pairwise comparisons).

Fig. 4.

Effect of drugs on plasma dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG). During the postprandial period, plasma DHPG levels were higher among subjects who received yohimbine alone or in combination with GLP-1. *P < 0.03 vs. placebo. †P < 0.03 vs. GLP-1 alone.

Plasma epinephrine levels were below the threshold of detection for the assay (i.e., <20 pg/ml) in most subjects (data not shown).

Effects of GLP-1, l-NMMA, and Yohimbine on Plasma Glucose

Drug effects on fasting and postprandial plasma glucose concentrations were significant. Compared with placebo, GLP-1 reduced (P < 0.05) fasting (i.e., 77 ± 3 mg% vs. 87 ± 3 mg%) and postprandial (i.e., 74 ± 5 mg% vs. 88 ± 4 mg%) plasma glucose concentrations. Similar effects were observed for GLP-1 and l-NMMA combined compared with GLP-1 alone (data not shown). However, yohimbine and l-NMMA did not have significant effects on plasma glucose concentrations (data not shown).

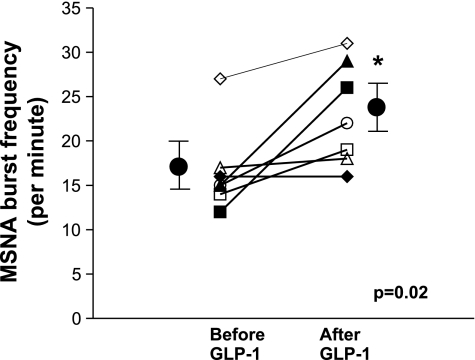

Effects of GLP-1 on Muscle Sympathetic Nerve Activity

GLP-1 increased muscle sympathetic nerve activity from 17 ± 2 to 23 ± 2 bursts/min (0.02 < P ≤ 0.05, signed rank test) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of GLP-1 on muscle sympathetic nerve activity. GLP-1 increased MSNA recorded under fasting conditions. *0.02 < P ≤ 0.05 vs. baseline (signed rank test).

DISCUSSION

In addition to regulating glycemia, there is evidence that the neuropeptide GLP-1, administered peripherally or centrally, inhibits vagal activity in animals and humans (19, 50, 51) and increases sympathetic activity in rats (52, 53). In this study, GLP-1 increased muscle sympathetic nerve traffic but did not affect heart rate, BP, plasma catecholamines, or cardiovagal and cardiosympathetic activity. GLP-1 increased MSNA by 25%, which is comparable to the rise in MSNA upon 30° head-upright tilt in healthy subjects (27) but smaller than the increase (i.e., 73 ± 13%) induced by yohimbine in a previous study (16). The lack of a control arm (i.e., sham infusion) in these studies is a potential limitation. However, in a controlled environment, MSNA is very stable within subjects, even over several weeks to months (13, 44). No blood was drawn while recording MSNA. Increased MSNA cannot be attributed to a small volume of fluid administered during GLP-1 infusion, which, if anything, would reduce, not increase MSNA. It is unclear whether GLP increased MSNA directly or by stimulating insulin secretion (24). Infusion of GLP-1 (7-36 amide) at a rate comparable to our studies increased plasma insulin concentrations on average from ∼8 to 15 mU/l (24), which is comparable to the insulin concentrations (i.e., 10 to 25 mU/l), which increased MSNA (i.e., from 16 to 25 bursts/min) during insulin euglycemic clamp infusion (17).

GLP-1 did not affect the heart rate and BP in experiment 1. Although GLP-1 increased systolic BP and had borderline significant effects on diastolic BP in experiment 2, these effects were numerically small. Overall, our observations are generally consistent with previous studies demonstrating that GLP-1 did not increase BP in monkeys (55) or during continuous subcutaneous infusion for 6 wk in humans (56). The demographic characteristics of subjects in experiments 1 and 2 were similar. Although GLP-1 increased MSNA in this study, our spectral analysis did not reveal changes consistent with an influence on cardiac sympathetic or parasympathetic activity. This is in contrast to data in rodents (55, 56). Perhaps we had insufficient statistical power to identify GLP-1-induced alterations in cardiac sympathetic or parasympathetic activity. Alternatively, the hemodynamic effects of increased sympathetic activity may have been masked by activation of baroreceptor reflexes or by the direct vascular effects of GLP-1 (6). In addition, GLP-1-induced insulin release might have interfered with sympathetic vasoconstriction (22, 39, 41). It is also conceivable that differences in the distribution of GLP-1 receptors on catecholaminergic neurons in the area postrema or central neural circuitry, may explain why GLP-1 had different effects on hemodynamic parameters in rats and humans.

The α2-adrenergic antagonist yohimbine increased power in the low-frequency component of HRV and systolic BP power spectra, indicating that despite their limitations (35, 47), these indices can identify increased cardiac sympathetic activity. In addition to augmenting sympathetic activity via central effects, it is also conceivable that the peripheral effects of yohimbine (i.e., blockade of α2-adrenoreceptors on sympathetic nerve endings) increase the amount of norepinephrine released from sympathetic nerve endings for a given amount of sympathetic nerve traffic (16). Moreover, yohimbine increased plasma norepinephrine and DHPG compared with placebo, and the combination of GLP-1 and yohimbine augmented plasma norepinephrine and DHPG compared with GLP-1 alone. The combined increase in plasma norepinephrine and DHPG concentrations indicates this was attributable to increased release rather than reduced reuptake of norepinephrine (15). As anticipated, the NOS inhibitor l-NMMA increased the diastolic BP and reduced the heart rate by reflex mechanisms (10) but did not affect the power spectral analysis of heart rate or BP in humans.

Perspectives and Significance

These observations provide direct evidence that GLP-1 increases sympathetic vasoconstrictor neural activity in humans. From a biological perspective, these observations are plausible since GLP-1 is produced in the brain and passively diffuses across the blood-brain barrier (21). Moreover, GLP-1 receptors are abundantly distributed throughout the central nervous system, including the brain stem. In addition to direct effects on GLP-1 receptors in the brain, the central effects of GLP-1 and/or exendin-4 may be mediated via peripheral effects (e.g., on the vagus) since a GLP-1 analog bound to albumin, which cannot readily cross the blood-brain barrier, inhibited food intake and gastric emptying and activated c-fos expression in mice, suggestive of central effects (4). Diabetes mellitus is associated with hypertension and autonomic neuropathy. Moreover, diabetic autonomic neuropathy is associated with significant increases in morbidity and mortality, including an increased risk of sudden death. (37, 42, 43) The effects of GLP-1 on MSNA need to be confirmed by larger studies in healthy subjects. Moreover, further studies of the effects of GLP-1 on sympathetic neural activity in diabetes mellitus, controlling for autonomic neuropathy and hypertension, are necessary.

GRANTS

This study was supported, in part, by U.S. Public Health Service National Institutes of Health Grant P01 DK-068055, and by the General Clinical Research Center Grant RR-00585 from the National Institutes of Health in support of the Physiology Laboratory and Patient Care Cores.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Mayo Clinic Research Pharmacy and the nursing staff of the General Clinical Research Center.

This article was presented in abstract form at the American Motility Society Meeting, Santa Monica, CA, September 22–25, 2005.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews CN, Bharucha AE, Camilleri C, Low PA, Seide B, Burton D, Nickander KK, Baxter K, Zinsmeister AR. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 and sympathetic stimulation on gastric accommodation in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19: 716–723, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews CN, Bharucha AE, Camilleri M, Low PA, Seide B, Burton D, Baxter K, Zinsmeister AR. Nitrergic contribution to gastric relaxation induced by glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in healthy adults. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G1359–G1365, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology [see comment]. Circulation 93: 1043–1065, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baggio LL, Huang Q, Cao X, Drucker DJ. An albumin-exendin-4 conjugate engages central and peripheral circuits regulating murine energy and glucose homeostasis. Gastroenterology 134: 1137–1147, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barragan JM, Eng J, Rodriguez R, Blazquez E. Neural contribution to the effect of glucagon-like peptide-1-(7-36) amide on arterial blood pressure in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 277: E784–E791, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basu A, Charkoudian N, Schrage W, Rizza RA, Basu R, Joyner MJ. Beneficial effects of GLP-1 on endothelial function in humans: dampening by glyburide but not by glimepiride. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1289–E1295, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bharucha AE, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, Hanson RB. Adrenergic modulation of human colonic motor and sensory function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 273: G997–G1006, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charkoudian N, Joyner MJ, Johnson CP, Eisenach JH, Dietz NM, Wallin BG. Balance between cardiac output and sympathetic nerve activity in resting humans: role in arterial pressure regulation. J Physiol 568: 315–321, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charkoudian N, Joyner MJ, Sokolnicki LA, Johnson CP, Eisenach JH, Dietz NM, Curry TB, Wallin BG. Vascular adrenergic responsiveness is inversely related to tonic activity of sympathetic vasoconstrictor nerves in humans. J Physiol 572: 821–827, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhary S, Vaile JC, Fletcher J, Ross HF, Coote JH, Townend JN. Nitric oxide and cardiac autonomic control in humans. Hypertension 36: 264–269, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenhofer G, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Catecholamine metabolism: a contemporary view with implications for physiology and medicine. Pharmacol Rev 56: 331–349, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenhofer G, Smolich JJ, Cox HS, Esler MD. Neuronal reuptake of norepinephrine and production of dihydroxyphenylglycol by cardiac sympathetic nerves in the anesthetized dog. Circulation 84: 1354–1363, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fagius J, Wallin BG. Long-term variability and reproducibility of resting human muscle nerve sympathetic activity at rest, as reassessed after a decade. Clin Auton Res 3: 201–205, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg MR, Hollister AS, Robertson D. Influence of yohimbine on blood pressure, autonomic reflexes, and plasma catecholamines in humans. Hypertension 5: 772–778, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein DS, Eisenhofer G, Stull R, Folio CJ, Keiser HR, Kopin IJ. Plasma dihydroxyphenylglycol and the intraneuronal disposition of norepinephrine in humans. J Clin Invest 81: 213–220, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grossman E, Rea RF, Hoffman A, Goldstein DS. Yohimbine increases sympathetic nerve activity and norepinephrine spillover in normal volunteers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 260: R142–R147, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hausberg M, Mark AL, Hoffman RP, Sinkey CA, Anderson EA. Dissociation of sympathoexcitatory and vasodilator actions of modestly elevated plasma insulin levels. J Hypertens 13: 1015–1021, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes C, Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS. Improved assay for plasma dihydroxyphenylacetic acid and other catechols using high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl 653: 131–138, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imeryuz N, Yegen BC, Bozkurt A, Coskun T, Villanueva-Penacarrillo ML, Ulusoy NB. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits gastric emptying via vagal afferent-mediated central mechanisms. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 273: G920–G927, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isbil-Buyukcoskun N, Gulec G. Investigation of the mechanisms involved in the central effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on ethanol-induced gastric mucosal lesions. Regul Pept 128: 57–62, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kastin AJ, Akerstrom V, Pan W. Interactions of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) with the blood-brain barrier. J Mol Neurosci 18: 7–14, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lembo G, Iaccarino G, Rendina V, Volpe M, Trimarco B. Insulin blunts sympathetic vasoconstriction through the alpha 2-adrenergic pathway in humans. Hypertension 24: 429–438, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meier JJ, Gallwitz B, Salmen S, Goetze O, Holst JJ, Schmidt WE, Nauck MA. Normalization of glucose concentrations and deceleration of gastric emptying after solid meals during intravenous glucagon-like peptide 1 in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 2719–2725, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier JJ, Gethmann A, Nauck MA, Gotze O, Schmitz F, Deacon CF, Gallwitz B, Schmidt WE, Holst JJ. The glucagon-like peptide-1 metabolite GLP-1-(9-36) amide reduces postprandial glycemia independently of gastric emptying and insulin secretion in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E1118–E1123, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merchenthaler I, Lane M, Shughrue P. Distribution of pre-pro-glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor messenger RNAs in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 403: 261–280, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montano N, Ruscone TG, Porta A, Lombardi F, Pagani M, Malliani A. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability to assess the changes in sympathovagal balance during graded orthostatic tilt [see comment]. Circulation 90: 1826–1831, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muenter Swift N, Charkoudian N, Dotson RM, Suarez GA, Low PA. Baroreflex control of muscle sympathetic nerve activity in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1226–H1233, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikolaidis LA, Elahi D, Shen YT, Shannon RP. Active metabolite of GLP-1 mediates myocardial glucose uptake and improves left ventricular performance in conscious dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H2401–H2408, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikolaidis LA, Mankad S, Sokos GG, Miske G, Shah A, Elahi D, Shannon RP. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 in patients with acute myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction after successful reperfusion. Circulation 109: 962–965, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novak P, Novak V. Time/frequency mapping of the heart rate, blood pressure and respiratory signals. Med Biol Eng Comput 31: 103–110, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nystrom T, Gonon AT, Sjoholm A, Pernow J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 relaxes rat conduit arteries via an endothelium-independent mechanism. Regul Pept 125: 173–177, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nystrom T, Gutniak MK, Zhang Q, Zhang F, Holst JJ, Ahren B, Sjoholm A. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on endothelial function in type 2 diabetes patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E1209–E1215, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pagani M, Lombardi F, Guzzetti S, Rimoldi O, Furlan R, Pizzinelli P, Sandrone G, Malfatto G, Dell'Orto S, Piccaluga E, Turiel M, Baselli G, Gerutti S, Malliani A. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res 59: 178–193, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagani M, Malfatto G, Pierini S, Casati R, Masu AM, Poli M, Guzzetti S, Lombardi F, Cerutti S, Malliani A. Spectral analysis of heart rate variability in the assessment of autonomic diabetic neuropathy. J Auton Nerv Syst 23: 143–153, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parati G, Mancia G, Di Rienzo M, Castiglioni P. Point: cardiovascular variability is/is not an index of autonomic control of circulation. [see comment]. J Appl Physiol 101: 676–678; discussion 681–672, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parati G, Saul JP, Di Rienzo M, Mancia G. Spectral analysis of blood pressure and heart rate variability in evaluating cardiovascular regulation. A critical appraisal. Hypertension 25: 1276–1286, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfeifer MA, Weinberg CR, Cook DL, Reenan A, Halter JB, Ensinck JW, Porte D Jr. Autonomic neural dysfunction in recently diagnosed diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care 7: 447–453, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russo A, Fraser R, Adachi K, Horowitz M, Boeckxstaens G. Evidence that nitric oxide mechanisms regulate small intestinal motility in humans. Gut 44: 72–76, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scherrer U, Randin D, Vollenweider P, Vollenweider L, Nicod P. Nitric oxide release accounts for insulin's vascular effects in humans. J Clin Invest 94: 2511–2515, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schirra J, Houck P, Wank U, Arnold R, Goke B, Katschinski M. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1(7-36)amide on antro-pyloro-duodenal motility in the interdigestive state and with duodenal lipid perfusion in humans. Gut 46: 622–631, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinberg HO, Brechtel G, Johnson A, Fineberg N, Baron AD. Insulin-mediated skeletal muscle vasodilation is nitric oxide dependent. A novel action of insulin to increase nitric oxide release. J Clin Invest 94: 1172–1179, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevens MJ, Raffel DM, Allman KC, Dayanikli F, Ficaro E, Sandford T, Wieland DM, Pfeifer MA, Schwaiger M. Cardiac sympathetic dysinnervation in diabetes: implications for enhanced cardiovascular risk. Circulation 98: 961–968, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suarez GA, Clark VM, Norell JE, Kottke TE, Callahan MJ, O'Brien PC, Low PA, Dyck PJ. Sudden cardiac death in diabetes mellitus: risk factors in the Rochester diabetic neuropathy study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76: 240–245, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sundlof G, Wallin BG. The variability of muscle nerve sympathetic activity in resting recumbent man. J Physiol 272: 383–397, 1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tack J, Demedts I, Meulemans A, Schuurkes J, Janssens J. Role of nitric oxide in the gastric accommodation reflex and in meal-induced satiety in humans. Gut 51: 219–224, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: the bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc 65: 1456–1479, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor JA, Studinger P. Counterpoint: cardiovascular variability is not an index of autonomic control of the circulation. J Appl Physiol 101: 678–681; discussion 681, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tolessa T, Gutniak M, Holst JJ, Efendic S, Hellstrom PM. Inhibitory effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 on small bowel motility. Fasting but not fed motility inhibited via nitric oxide independently of insulin and somatostatin. J Clin Invest 102: 764–774, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei Y, Mojsov S. Tissue-specific expression of the human receptor for glucagon-like peptide-I: brain, heart and pancreatic forms have the same deduced amino acid sequences. FEBS Lett 358: 219–224, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wettergren A, Petersen H, Orskov C, Christiansen J, Sheikh SP, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1 7-36 amide and peptide YY from the L-cell of the ileal mucosa are potent inhibitors of vagally induced gastric acid secretion in man. Scan J Gastroenterol 29: 501–505, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wettergren A, Wojdemann M, Meisner S, Stadil F, Holst JJ. The inhibitory effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) 7-36 amide on gastric acid secretion in humans depends on an intact vagal innervation. Gut 40: 597–601, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamamoto H, Kishi T, Lee CE, Choi BJ, Fang H, Hollenberg AN, Drucker DJ, Elmquist JK. Glucagon-like peptide-1-responsive catecholamine neurons in the area postrema link peripheral glucagon-like peptide-1 with central autonomic control sites. J Neurosci 23: 2939–2946, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto H, Lee CE, Marcus JN, Williams TD, Overton JM, Lopez ME, Hollenberg AN, Baggio L, Saper CB, Drucker DJ, Elmquist JK. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor stimulation increases blood pressure and heart rate and activates autonomic regulatory neurons. J Clin Invest 110: 43–52, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto H, Mori T, Tsuchihashi H, Akabori H, Naito H, Tani T. A possible role of GLP-1 in the pathophysiology of early dumping syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 50: 2263–2267, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young AA, Gedulin BR, Bhavsar S, Bodkin N, Jodka C, Hansen B, Denaro M. Glucose-lowering and insulin-sensitizing actions of exendin-4: studies in obese diabetic (ob/ob, db/db) mice, diabetic fatty Zucker rats, and diabetic rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Diabetes 48: 1026–1034, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zander M, Madsbad S, Madsen JL, Holst JJ. Effect of 6-week course of glucagon-like peptide 1 on glycaemic control, insulin sensitivity, and beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes: a parallel-group study. Lancet 359: 824–830, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]