Abstract

A set of aliphatic and aromatic aldehyde-derived hydrazone(HZ)-based acid-sensitive polyethylene glycol-phosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-PE) conjugates was synthesized and evaluated for their hydrolytic stability at neutral and slightly acidic pH values. The micelles formed by aliphatic aldehyde-based PEG-HZ-PE conjugates were found to be highly sensitive to mildly acidic pH and reasonably stable at physiologic pH, while those derived from aromatic aldehydes were highly stable at both pH values. The pH-sensitive PEG-PE conjugates with controlled pH-sensitivity may find applications in biological stimuli-mediated drug targeting for building pharmaceutical nanocarriers capable of specific release of their cargo at certain pathological sites in the body (tumors, infarcts) or intracellular compartments (endosomes, cytoplasm) demonstrating decreased pH.

INTRODUCTION

The development of an optimal drug delivery systems has the utmost importance in contemporary medicine (1). The ultimate goal in drug delivery is to achieve therapeutic concentrations of the drug at the target site while drug concentrations at other tissues are kept in safe levels. This has a particular importance in case of cancer treatment, where the challenge is to selectively destroy the tumor without damaging normal tissues. Disease (tumor) site-specific targeting of drugs and drug carriers may, at least partially, solve the problem. The issue however remains, how to achieve fast and effective drug release from the pharmaceutical carrier when it has already reached its target, such as tumor (2–4). This issue is equally important when long-circulating PEGylated drug delivery systems are used (5–7), since PEG prevents normal interaction of the carrier with cells and other destabilizing factors, or when drug carrier is intended for the intracellular penetration (8, 9) and a properly scheduled cytoplasmic release of the active drug is expected to prevent its degradation in lysosomes (10).

There are several approaches to this problem including the use of stimuli-sensitive pharmaceutical nanocarriers, which is based on the fact that many pathological sites including tumors demonstrate hyperthermia or acidification (11–13). In general, environmentally-sensitive carriers exhibit dramatic changes in their swelling behavior, network structure, permeability, or stability in response to changes in the pH or ionic strength of the surrounding fluid or temperature (14). Such systems, for example, may include certain pH-sensitive linkages allowing for drug release, protective “coat” removal, or new function appearance because of their fast degradation in acidified pathological sites (15–17). Different approaches have been employed to develop pH-responsive carriers, one being incorporation of acid-sensitive linkages between drug-ligand or into the molecules of the carrier-forming components. These include cis-aconityls (18, 19), electron-rich trityls (20), polyketals (21), acetals (22, 23), vinyl ethers (24, 25), hydrazones (26–28), poly(ortho-esters) (29), and thiopropionates (30). Such constructs may turn out to be useful for the site-specific delivery of drugs at the tumor sites(12), infarcts (31), inflammation zones (32) or cell cytoplasm or endosomes (33), since at these “acidic” sites, pH drops from the normal physiologic value of pH 7.4 to pH 6.0 and below.

We have recently demonstrated the utility of highly pH-sensitive hydrazone bond-based PEG-PE conjugates in preparing double-targeted stimuli-sensitive pharmaceutical nanocarriers (34). This proof-of-principle study did not, however, address an important issue of the proper coordination between two important temporal characteristics of such carriers, which are expected to demonstrate a sufficiently long life-time under normal physiological conditions allowing for their efficient accumulation in the target, and sufficiently fast destabilization within the acidic target providing a better drug penetration into the target cells. Since real practical tasks may require different times for such carriers to stay in the blood and to release their contents (or “develop” an additional function) inside the target, the need is evident to have a set of pH-sensitive conjugates capable of serving as components of stimuli-sensitive pharmaceutical nanocarriers and demonstrating variable stabilities at normal and acidic pH values.

With this in mind, we have synthesized a series of PEG-HZ-PE conjugates with different substituents at the hydrazone bond and evaluated their hydrolytic stability at normal and slightly acidic pH values. These conjugates differ from each other with respect to the exact structure of groups forming the hydrazone linkage between phospholipid and PEG. The characterization of the in vitro behavior of these conjugates has provided an important information useful for future design and development of pH-sensitive nanocarriers with desired properties.

MATERIALS

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, DOPE; 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanolamine (Sodium Salt), DPPE-SH; and l,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) ammonium salt, Rh-PE, were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster (AL); (N-e-maleimidocaproic acid) hydrazide, EMCH; 4-(4-N-maleimidophenyl) butyric acid hydrazide hydrochloride, MPBH; N-(k-maleimidoundecanoic acid) hydrazide, KMUH; succinimidyl 4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxylate, SMCC were purchased from Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL. 2-acetamido-4-mecrcapto butanoic acid hydrazide, AMBH was purchased from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); methoxy poly(ethylene) glycol butyraldehyde (MW 2000), mPEG-SH (MW 2000), were purchased from Nektar Therapeutics (Huntsville, AL). Triethylamine was purchased from Aldrich Chemicals. 4-succinimidyl formylbenzoate (SFB) was purchased from Molbio (Boulder, Colorado). All solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (HPLC grade) and used without further purification.

SYNTHESES

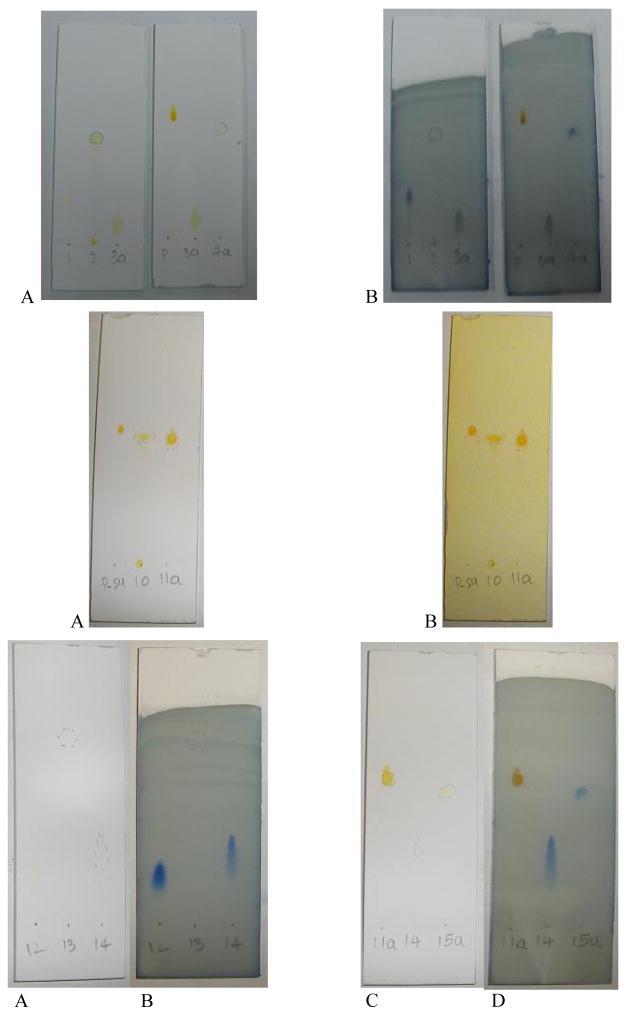

All reactions were monitored by TLC using 0.25 mm × 7.5 cm silica plates with UV-indicator (Merck 60F-254), and mobile phase of chloroform:methanol (80:20% v/v). Phospholipid and PEG alone or their conjugates were visualized by iodine, phosphomolybdic acid, and Dragendorff spray reagents (Figure 1). Silica gel (240–360 μm) and size exclusion media, Sepharose CL4B (40–165 μm) and Sephadex G25m (Sigma-Aldrich) were used for silica column chromatography and size exclusion chromatography respectively.

Figure 1.

Representative TLC patterns of different reactants and purified products.

Upper row: For the schemes 1 and 2 with iodine (A), or phosphomolybdenum spray (B) visualization. (1: DPPE-SH, 2: EMCH linker, 3a: EMCH-activated phospholipid, P: PEG-butyraldehyde, 4a: PEG-HZ-PE conjugate).

Middle row: For the scheme 6 with iodine (A) or Dragendorff spray (B) visualization. (P-SH: PEG-SH, 10: EMCH linker, 11 a: EMCH activated PEG)

Bottom row: For the schemes 7 and 8 with iodine (A, C) or phosphomolybdenum spray (B, D) visualization, (11a: EMCH activated PEG, 12: DOPE, 13: SFB, 14: SFB activated DOPE, 15a: PEG-HZ-PE).

1H-NMR spectra were obtained on Varian Unity AS500 instrument (500MHz). Chemical shifts (δ) were given in ppm relative to TMS.

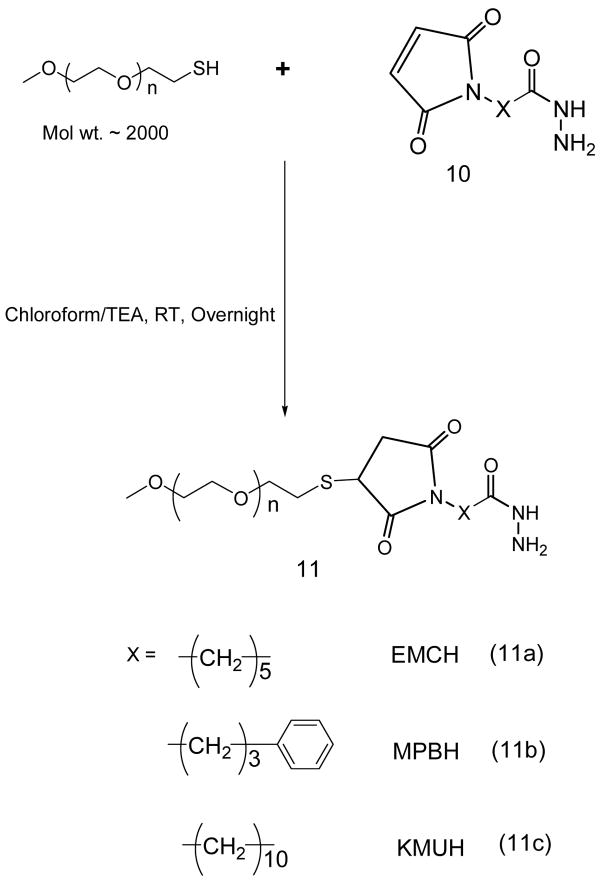

Hydrazide activated phospholipids (3a, 3b, 3c)

22 μmoles of phosphatidylthioethanolamine, 2, were mixed with 1.5 molar excess of each acyl hydrazide linker (Table 1) in 3 mL anhydrous methanol containing 5 molar excess of triethylamine over lipid (Scheme 1). The reaction was performed at 25°C under argon for 8 h. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was dissolved in chloroform and applied to a 5-mL silica gel column which had been activated (150°C overnight) and pre-washed with 20 mL of chloroform. The column was equilibrated with an additional 15 mL of chloroform followed by 5 mL of each of the following chloroform:methanol mixtures 4:0.25, 4:0.5, 4:0.75, 4:1, 4:2 and, finally, with 6 mL of 4:3 v/v. The phosphate-containing fractions eluting in 4:1, 4:2 and 4:3 chloroform:methanol (v/v) were pooled, concentrated under reduced pressure. The yields of the 3a, 3b, and 3c were 65.7, 71.9, and 68%, respectively. The products were stored in glass ampoules as chloroform solutions under argon at −80°C.

Table 1.

Acyl hydrazide linkers used in this study

| Linker (X) | Mol. Wt. | Length of Spacer arm |

|---|---|---|

| AMBH 2-acetamido-4-mercapto butanoic acid hydrazide | 191.25 | - |

| EMCH (N-e-maleimidocaproic acid) hydrazide | 225.24 | 11.8 A |

| MPBH 4-(4-N-maleimidophenyl)butyric acid hydrazide | 309.5 | 17.9 A |

| KMUH N-(k-maleimido undecanoic acid) hydrazide | 295.8 | 19.0 A |

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of acyl hydrazide-activated phospholipids.

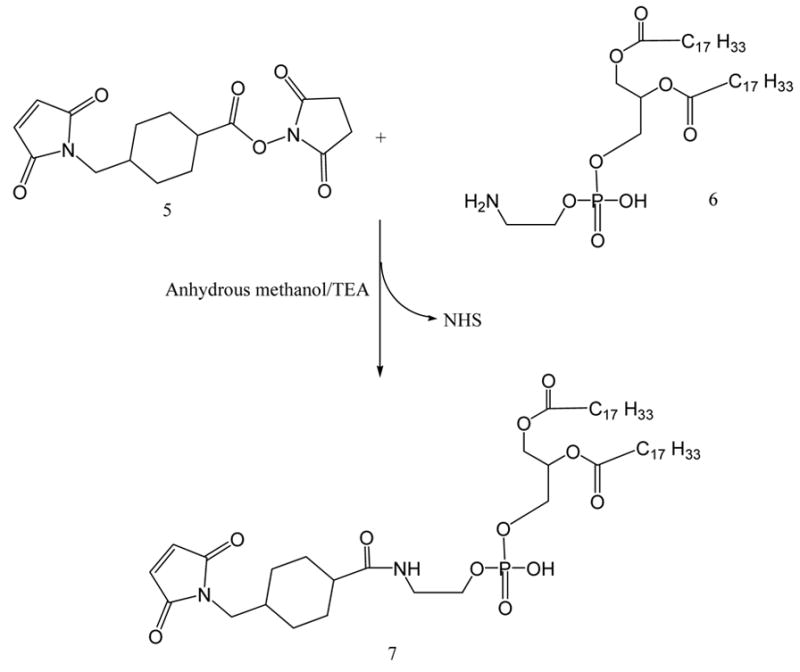

For the activation of phospholipid with AMBH, a maleimide derivative of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), 7, was prepared using SMCC (Scheme 3). In brief, PE, 6, in chloroform was reacted with 1.5 molar excess of SMCC, 5, over lipid in presence of 5 molar excess of TEA under argon for 5 h. The maleimide-derivative was separated from excess SMCC on silica gel column using chloroform:methanol (4:0.2 v/v) mobile phase. The elution fractions containing Ninhydrin-negative and phosphorus-positive fractions were pooled and concentrated under reduced pressure The yield of the product was 65.7%.

Scheme 3.

Maleimide activation of phosphatidylethanolamine

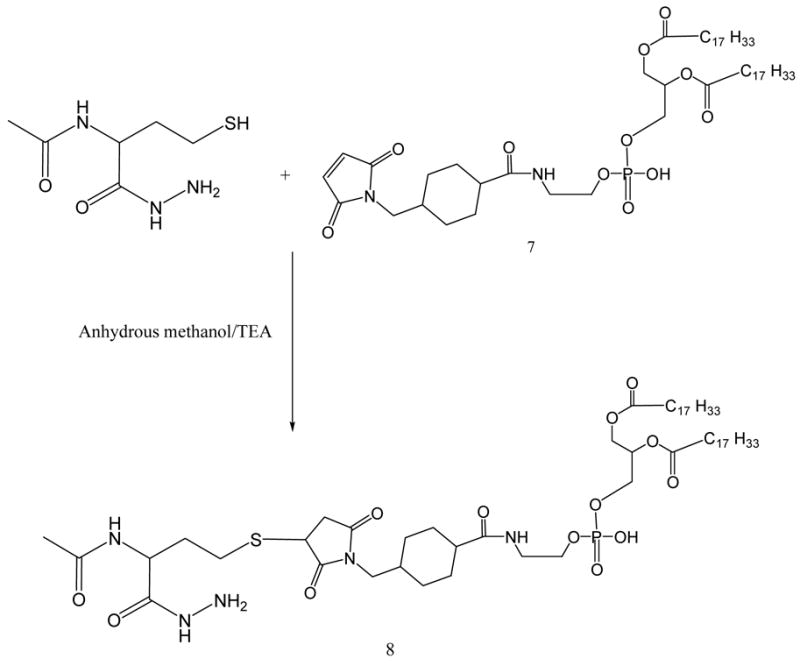

DOPE-maleimide was further used to synthesize AMBH-activated derivative of phospholipid, 8, by reacting with 1.5 molar excess of AMBH using TEA as catalyst (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

AMBH-derivatized phospholipid via sulfhydryl-maleimide addition reaction

1H NMR spectroscopy

EMCH activated phospholipid derivative, (3a)

1H NMR (500MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.85– 0.87 (t, 6H, 20), 1.25–1.32 (m, 46H), 1.39 (d, 2H, 35), 1.56–1.64 (m, 8H), 2.25 (m, 12H), 3.06–3.08 (m, 5H), 3.48 (m, 3H), 7.12–7.19 (d, 2H, 35), 7.32 (s, 3H).

MPBH activated phopsholipid derivative, (3b)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.85– 0.89 (t, 6H, 20), 1.11 (s, 5H), 1.18 (s, 12H), 1.25–1.30 (m, 44H), 1.56–1.60 (m, 8H), 2.26 (m, 4H), 3.49 (s, 1H), 7.12 (s, 1H), 7.19 (s, 2H), 7.32 (s, 4H).

KMUH activated phospholipid derivative, (3c)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.85– 0.89 (t, 6H, 20), 1.11 (s, 3H), 1.25–1.30 (m, 52H), 1.30–1.35 (m, 4H), 1.57–1.60 (m, 4H), 2.13–2.29 (m, 6H), 3.08–3.11 (m, 8H), 3.48 (m, 3H), 3.90–3.96 (m, 5H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.32 (s, 2H).

AMBH activated phospholipid derivative, (8)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.85–0.90 (t, 6H, 25), 1.26–1.29 (m, 41H), 1.57 (s, 8H), 1.80–1.84 (m, 5H), 2.01 (m, 19H), 2.17 (d, 6H, 2.5), 2.27–2.29 (d, 5H, 10), 2.69 (s, 2H), 3.37–3.40 (m, 3H), 3.86–3.88 (m, 4H), 4.09–4.11 (m, 1H), 5.3 (m, 3H)

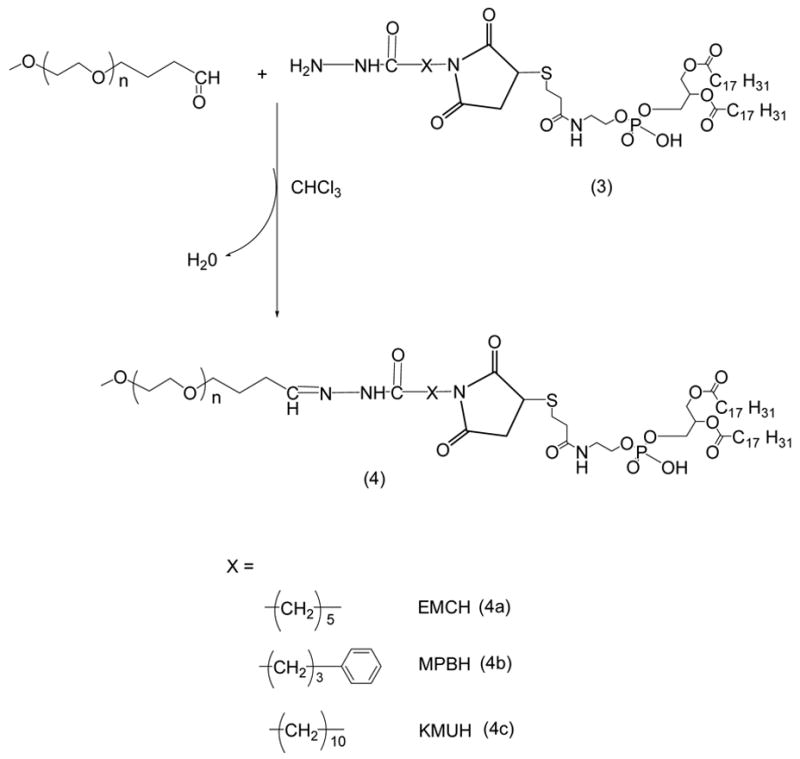

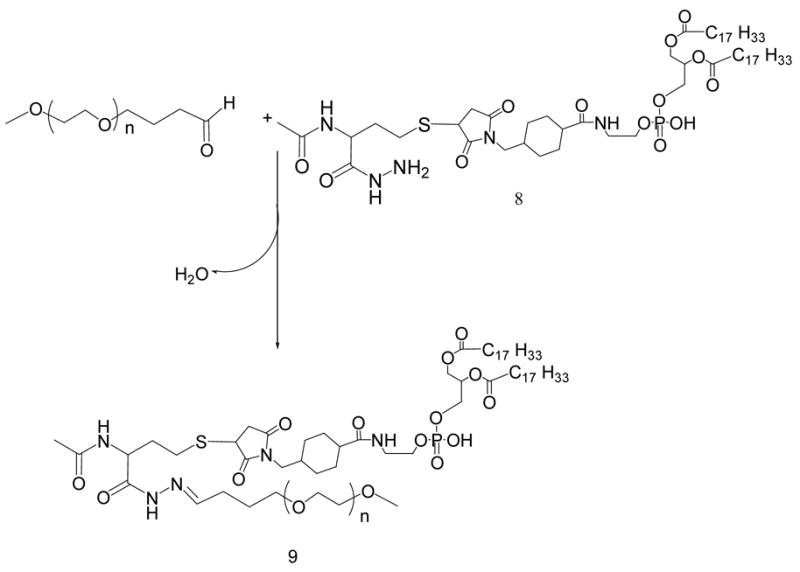

PEG-HZ-PE conjugates (4a. 4b. 4c. 9)

21 μmoles of mPEG2000-butyraldehyde were reacted with 14 μmoles of linker-activated phospholipid in 2 ml chloroform at 25°C in a tightly closed reaction vessel (Schemes 2 and 5). After an overnight stirring, chloroform was evaporated under vacuum in rotary evaporator. The excess mPEGiooo-butyraldehyde was separated from PEG-HZ-PE conjugates using gel filtration chromatography. The gel filtration chromatography was performed using sepharose-CL4B equilibrated overnight in pH 9–10 degassed ultra pure water (elution medium) in 1.5 × 30 cm glass column. The thin film formed in round bottom flask after evaporating chloroform was hydrated with the elution medium and applied to the column. The micelles formed by PEG-HZ-PE conjugate were the first to elute from the column. Micelle containing fractions were identified by Dragendorff spray reagent and pooled together, kept in freezer at −80°C overnight before subjecting to freeze drying. The freeze-dried PEG-HZ-PE conjugates were weighed and stored at −80°C as chloroform solutions. The yields of 4a, 4b, 4c and 9 were 55.1, 57.4, 53.5, and 61.0%, respectively.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of PEG-HZ-PE conjugates.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of PEG-HZ-PE conjugate using AMBH-activated phospholipid

1H NMR spectroscopy

PEG-HZ-PE conjugate with EMCH cross-linker, (4a)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.85–0.88 (t, 6H, 15), 1.25–1.27 (m, 44H), 1.55–1.60 (m, 9H), 2.12–2.20 (m, 106H), 2.68 (s, 22H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 3.49–3.59 (m, 240H), 3.90–3.92 (m, 9H), 4.2 (s, 6H), 4.67–4.7 (m, 1H), 5.31–5.33 (m,2H)

PEG-HZ-PE conjugate with MPBH cross-linker, (4b)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.87–0.94 (t, 6H, 10), 1.25(m, 54H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 3.5–3.69 (m, 243H), 7.19 (m, 3H), 7.32 (s, 5H)

PEG-HZ-PE conjugate with KMUH cross-linker, (4c)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.85–0.88 (t, 6H, 15), 1.24–1.3 (m, 54H), 1.56–1.57 (m, 8H), 1.9–2.0 (m, 49H), 2.26–2.28 (m, 5H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 3.47–3.49 (m, 7H), 3.50–3.53 (m, 9H), 3.55–3.65 (m, 240H), 3.67 (s, 5H), 3.7–3.76 (m, 2H), 5.31–5.33 (m, 1H).

PEG-HZ-PE conjugate with AMBH cross-linker, (9)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.86–0.89 (t, 6H, 15), 1.29–1.32 (m, 54H), 1.68 (m, 104H), 1.99 (m, 13H), 2.15 (m, 58H), 2.33–2.34 (m, 4H), 2.46 (m, 1H), 3.0 (m, 1H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 3.54–3.57 (m, 243H), 3.77– 3.78 (t, 1H, 5), 5.33–5.34 (m, 2H).

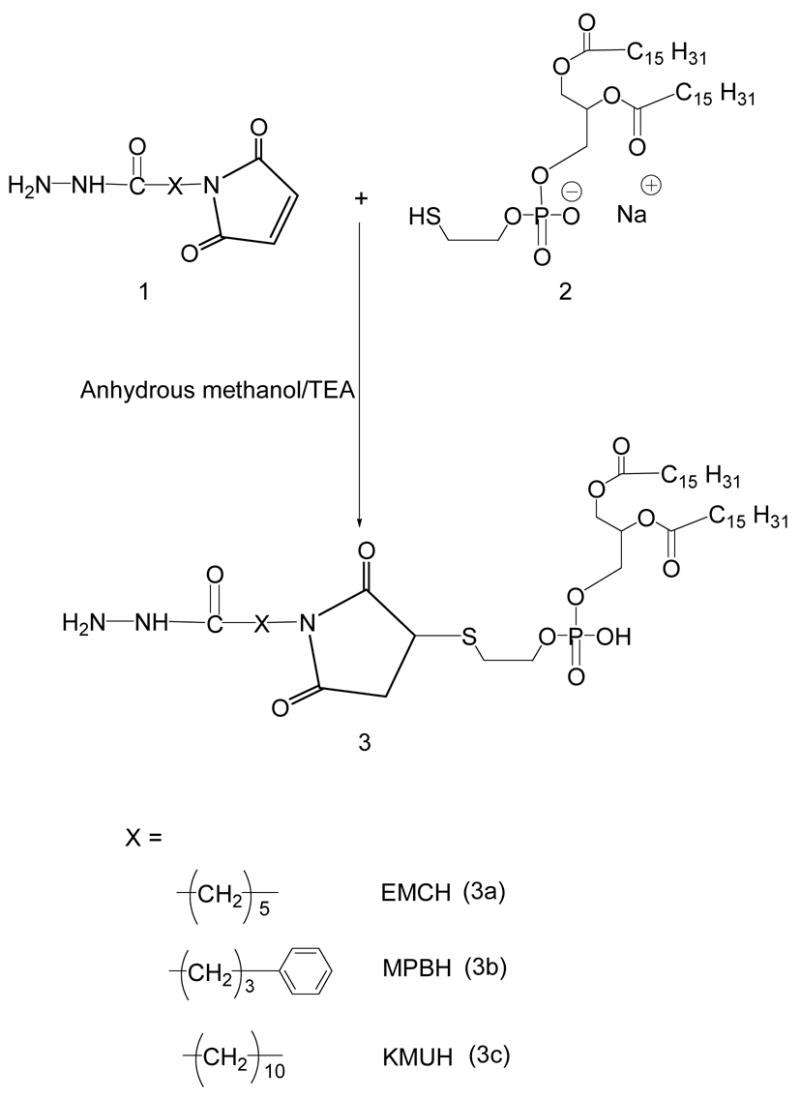

Hydrazide activated PEG derivatives, (11a, 11b, 11c)

40 μmoles of mPEG-SH in chloroform were mixed with two molar excess of acyl hydrazide cross-linkers: EMCH (10a), MPBH (10b), KMUH (10c) presence of 5 molar excess of triethylamine over lipid. The excess EMCH was separated from the product by size exclusion chromatography using Sephadex G25m media. The acyl hydrazide derivatives of PEG, (11a), (11b), (11c) were freeze dried, weighed (yields 80.3, 80.5 84%, respectively) and stored as chloroform solutions at −80°C.

1H NMR spectroscopy

EMCH activated PEG derivative, (11a)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.21 (s, 1H), 1.3 (s, 1H), 1.6 (m, 2H), 1.78 (s, 1H), 1.86 (s, 1H) 1.96 (s, 1H), 2.09–2.11 (m, 29H), 2.42–2.46 (m, 3H), 2.57–2.64 (m, 2H), 3.07–3.14 (m, 1H), 3.34 (s, 3H), 3.45–3.51 (m, 8H), 3.54–3.62 (m, 236H), 3.68–3.71 (t, 2H, 15), 3.73–3.75 (t, 1H, 10), 7.01–7.11 (m, 1H)

MPBH activated PEG derivative, (11b)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.25 (s, 1H), 1.71–1.8 (d, 19H, 45), 1.98 (s, 2H), 2.16–2.17 (d, 18H, 5), 2.48 (m, 1H), 2.64–2.73 (m, 2H), 3.37(s, 3H), 3.53–3.69 (m, 183H), 7.18–7.20 (d, 1H, 10), 7.31–7.32 (d, 1H, 5).

KMUH activated PEG derivative, (11c)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.27–1.33 (m, 18H), 1.53–1.56 (m, 3H), 1.18 (s, 3H), 1.96–2.03 (m, 25H), 2.16 (m, 43H), 2.45–2.49 (m, 5H), 2.60–2.63 (t, 2H, 5), 3.11–3.17 (m, 2H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 3.48–3.68 (m, 236H).

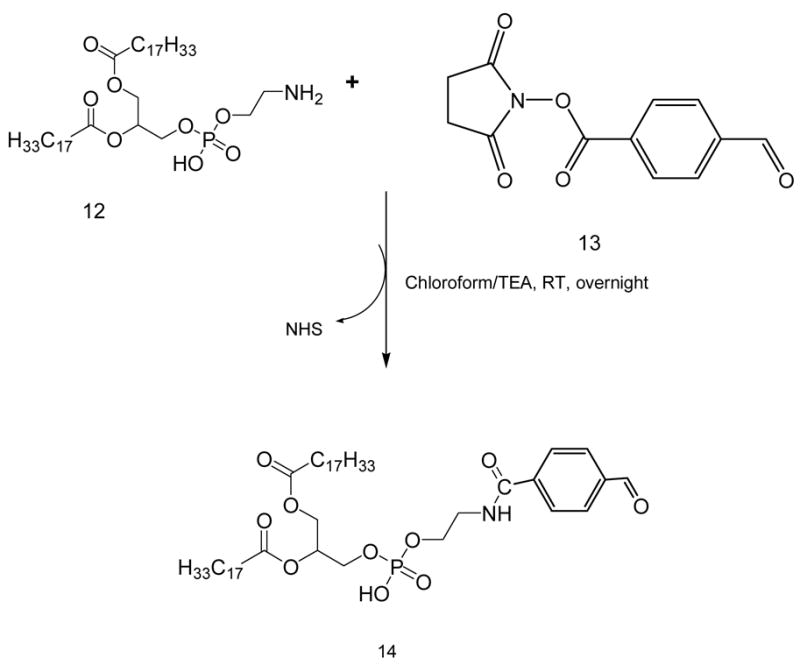

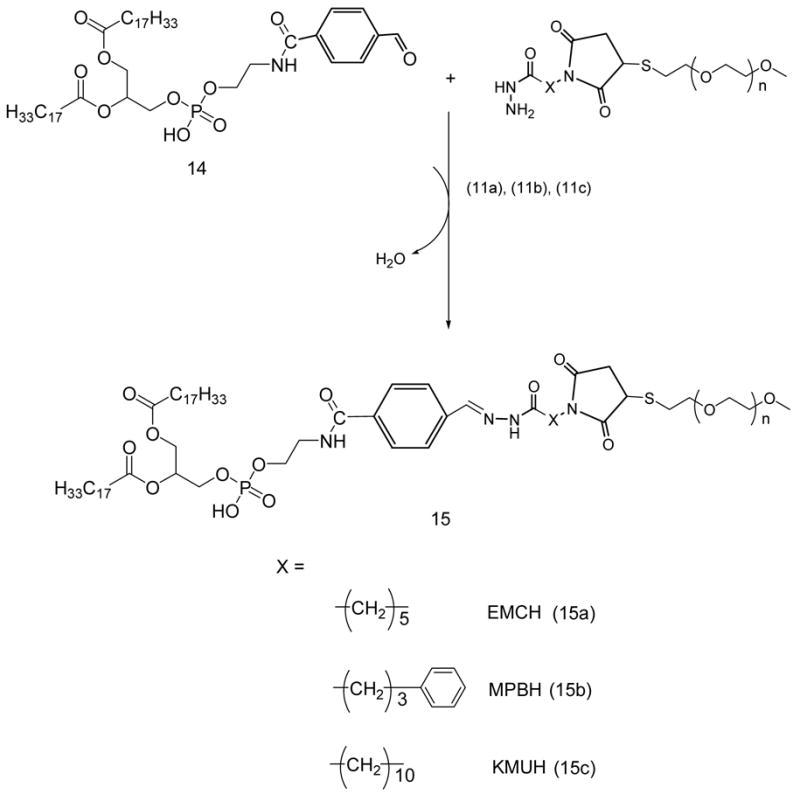

4-Succinimidyl formyl benzoate (SFB) activated Phospholipid (14)

35 μmoles of phosphatidylethanolamine, DOPE-NH2, 12, in chloroform were mixed with 2 molar excess of 4-succinimidylformyl benzoate, 13, in presence of 3 molar excess triethylamine over lipid. After stirring for 3 h, solvent was evaporated, residue was redissolved in chloroform and product was separated on silica gel column using acetonitrile:methanol mobile phases: 4:0, 4:0.25, 4:0.5, 4:0.75 and 4: 1 v/v. The fractions containing the product were identified by TLC analysis, pooled and concentrated. The yield was 73%. The product was stored as chloroform solution at −80°C.

1H NMR spectroscopy

SFB activated phospholipid, (14)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.85 (t, 6H, 15), 1.21–1.29 (m, 45H), 1.5 (s, 4H), 1.96 (d, 8H, 10), 2.19 (d, 4H, 25), 2.6 (s, 2H), 3.0 (m, 1H), 3.64 (m, 2H), 3.9–4.04 (m, 4H), 5.30–5.34 (m, 4H), 7.84–7.87 (t, 3H, 15), 8.05–8.13 (m, 3H), 9.98–10.05 (d, 1H, 35)

PEG-HZ-PE conjugates (15a. 15b. 15c)

1.5 molar excess of SFB-activated phospholipid, 14, was reacted with acyl hydrazide-derivatized PEGs, 11a, 11b, and 11c, respectively, in chloroform at room temperature. After the overnight stirring, chloroform was evaporated under reduced pressure. The PEG-HZ-PE conjugate was purified using size exclusion chromatography using Sepharose CL4B as described before. The yields of the conjugates 15a, 15b, and 15c were 57.8, 65.4 and 62%, respectively.

1H NMR spectroscopy

PEG-HZ-PE conjugate with EMCH activated PEG, (15a)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.84–0.86 (t, 6H, 10), 1.23–1.30 (m, 45H), 1.63 (s, 40H), 1.96–2.00 (m, 9H), 2.15 (s, 4H), 2.24–2.28 (q, 5H, 15), 2.53–2.55 (t, 2H), 3.35 (s, 3H), 3.55–3.66 (m, 232H), 3.75–3.76 (m, 1H), 3.98–4.04 (q, 3H, 7.5), 4.16–4.20 (m, 1H), 4.39–4.41 (m, 1H), 5.30–5.33 (m, 4H), 7.64–7.66 (d, 2H, 10), 7.75 (s, 1H), 8.0 (d, 2H, 10)

PEG-HZ-PE conjugate with MPBH activated PEG, (15b)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.86–0.88 (t, 6H, 10), 1.26 (m, 54H), 1.56–1.57 (m, 4H), 1.71 (s, 18H), 1.99–2.00 (d, 6H, 5), 2.17 (s, 1H), 2.25–2.26 (m, 3H), 3.37(s, 3H), 3.54–3.77 (m, 181H), 5.22–5.34 (m, 2H), 7.29–7.31 (d, 1H, 15), 7.58 (s, 1H), 8.01 (m, 1H)

PEG-HZ-PE conjugate with KMUH activated PEG, (15c)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.86–0.88 (t, 6H, 10), 1.26–1.28 (m, 62H), 1.55–1.65 (m, 56H), 1.99–2.00 (d, 20H, 5), 2.04 (s, 6H), 2.12 (s, 16H), 2.16 (m, 40H), 2.20 (m, 11H), 2.27–2.29 (m, 12H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 3.54–3.67 (m, 248H), 5.33 (m, 7H).

Micelle size measurement

The micelle size (hydrodynamic diameter) was measured by the dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a N4 Plus Submicron Particle System (Coulter Corporation, Miami, FL) at PEG-PE concentration of 10 mM.

In vitro pH-dependant degradation of PEG-HZ-PE conjugates

The time-dependant degradation of PEG-HZ-PE micelles incubated in buffer solutions (phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4 and pH 5.5) maintained at 37°C was followed by HPLC using Shodex KW-804 size exclusion column as described in (34). In brief, the elution buffer used was pH 7.0, Phosphate buffer (100 mM phosphate, 150 mM sodium sulfate), run at 1.0 ml/min. For fluorescent detection (Ex 550nm/Em 590nm) of micelle peak, Rh-PE (1 mol % of PEG-PE) was added to the PEG-PE conjugate in chloroform. A film was prepared by evaporating the chloroform under argon stream and hydrated with the phosphate buffer saline, pH 7.4 or 5.5 (adjusted by pre-calculated quantity of 1N HCl). A peak that represents micelle population appeared at the retention time between 9–10 minutes. The degradation kinetics of micelles was assessed by following the area under micelle curve.

DISCUSSION

Synthesis of hydrazone-based PEG-PE conjugates

The success of hydrazones as pH-sensitive linkages derives from the fact that their hydrolytic stability is governed by the nature of hydrazone bond formed. Hydrazones are much more stable than imines as a result of the delocalization of the π-electrons in the former. In fact, parent hydrazones are too stable for the application in drug delivery systems, and an electron withdrawing group has to be introduced to moderate the stability by somewhat disfavoring electron delocalization throughout the molecule as compared to the parent hydrazone. Hydrazones can be prepared from aldehydes or ketones and hydrazides under very mild conditions including aqueous solutions. Hydrazone bond formation can take place even in vivo from separate fragments which self-assemble under physiological conditions (35).

In this work, we have applied different synthetic methods based on the use of various aldehydes that can produce the hydrazone linkage between PEG and PE. We have also conducted studies to check hydrolytic stability of hydrazones derived from aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes and different acyl hydrazides. Synthesis of aliphatic aldehyde-derived hydrazone containing PEG-PE conjugate was pursued in two steps. First, phospholipid was activated with four different acyl hydrazides. The sulfhydryl reactive group of phosphatidylthioethanolamine was reacted with maleimide end of maleimido acyl hydrazides (refer Table 1) through Michael addition, thus providing acyl hydrazide-activated PE. mPEG-butyraldehyde, an aliphatic aldehyde, was then reacted with acyl hydrazide-activated PE to get a hydrazone-based PEG-PE conjugate. 1H-NMR analysis was performed on synthesized conjugates using comparisons with both starting materials.

To synthesize aromatic aldehyde-derived hydrazone, an aromatic aldehyde moiety was introduced into the phospholipid by reacting succinimidyl 4-formylbenzoate (SFB) with PE under mild alkaline conditions. The acyl hydrazide-PEG derivatives were synthesized using mPEG-SH and maleimido acyl hydrazides (EMCH, MPBH, and KMUH). The SFB-activated phospholipid was then reacted with acyl hydrazide derivatized PEG. The identity of aromatic aldehyde derived PEG-HZ-PE conjugates was confirmed by 1H-NMR.

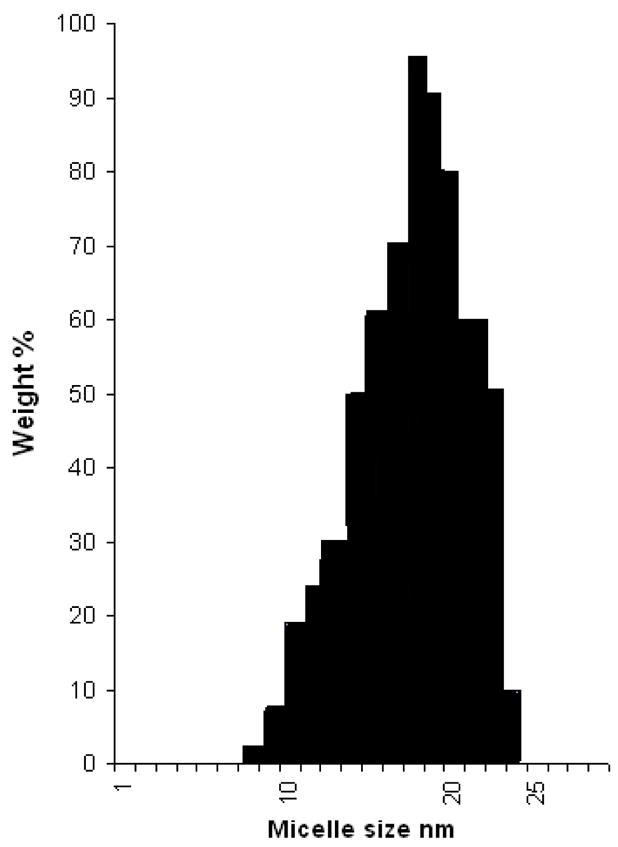

Particle size measurement

All synthesized conjugates spontaneously self-assemble into micelles in aqueous solutions. The typical size distribution pattern of the micelles assembles from the representative PEG-HZ-PE conjugate, 15 a, is presented in Figure 2. As the measurements indicate, a exhibited the size of 8–24 nm that is characteristic for typical PEG-PE micelles (36,37). All synthesized PEG-HZ-PE conjugates followed similar micelle size and distribution pattern.

Figure 2.

Typical particle size distribution pattern for PEG-HZ-PE conjugate miceles, (compound 15a).

In vitro pH-dependant degradation of PEG-HZ-PE conjugates

The stability of hydrazone-based PEG-PE conjugates incubated at physiological pH 7.4 and acidic pH 5.5 in buffer solutions maintained at 37°C was investigated by HPLC. For this purpose, the area under the micelle peak of PEG-HZ-PE (Rt 9–10 min) was observed over a period of time. PEG-HZ-PE conjugates derived from an aliphatic aldehyde and different acyl hydrazides were found to be highly unstable under acidic conditions, with the micelle peak was completely disappearing within 2 min incubation at pH 5.5. At the same time, these conjugates were relatively stable at physiological pH: the PEG-HZ-PE conjugate, 9, with AMBH as cross-linker showed the half-life of 150 min followed by EMCH, 4a, (120 min), MPBH, 4b, (90 min), and KMUH, 4c, (20 min) (Table 2). The hydrolysis rate of the aliphatic aldehyde-derived hydrazone-based PEG-PE conjugates (4a, 4b, 4c, and 9) at pH 7.4 seems to be dependant on carbon chain length of acyl hydrazide. The increase in the number of carbon atoms in acyl hydrazide led to an increase in the rate of hydrolysis (PEG-PE conjugate 4c, acyl hydrazide with 10 C atoms > 4a, acyl hydrazide with 5 C atoms > 9, acyl hydrazide with 3 C atoms). Introducing an aromatic character within the carbon chain of acyl hydrazide led to an increase in the hydrolysis rate as observed in case of 4b and 4a (the rate of hydrolysis of 4b > 4a). One has to note the precipitate (lipid) formation as hydrolysis of the hydrazone bond proceeds.

Table 2.

Half-lives of aliphatic aldehyde-based hydrazone derived mPEG-HZ-PE conjugates in phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4, at 37°C, min.

| mPEG-HZ-PE Conjugate | Half-life (min) | |

|---|---|---|

| pH 7.4 | pH 5.5 | |

| 4a | 120 | <2 |

| 4b | 90 | <2 |

| 4c | 20 | <2 |

| 9 | 150 | <2 |

Alternatively, the PEG-HZ-PE conjugates derived from an aromatic aldehyde and acyl hydrazides were found to be highly stable at pH 7.4 and 5.5 (Table 3). The half-life values were not attained at either of those pH values even at the end of the incubation period of 72 h at pH 7.4 and 48 h at pH 5.5 in buffer solutions maintained at 37°C. The resistance to hydrolysis exhibited by hydrazones derived from aromatic aldehydes can be attributed to the conjugation of the π bonds of -C=N- bond of the hydrazone with the π bonding benzene ring. This observation supports the finding that hydrazones formed from aromatic aldehydes are more stable to acidic hydrolysis than those formed from aliphatic ones (38, 39). The hydrazone hydrolysis involves the protonation of the -C=N nitrogen followed by the nucleophilic attack of water and cleavage of C-N bond of tetrahedran intermediate (40). Any of these steps is determining and dependent on the pH. The substituents on the carbonyl reaction partner influence the rate of hydrolysis through altering the pKa of the hydrazone with electron donating substituents facilitating protonation of the -C=N nitrogen (41). It is important to note here, that “direct” PEG-PE conjugates with no HZ linkage between PEG and PE moieties used by us as controls in this and other studies (34,36,37), do not demonstrate any hydrolysis at tested pH values over extended periods of time.

Table 3.

Half-lives of aromatic aldehyde-based hydrazone derived mPEG-HZ-PE conjugates in phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4, at 37°C, h.

| mPEG-HZ-PE Conjugate | Half-life (min) | |

|---|---|---|

| pH 7.4 | pH 5.5 | |

| 15a | >72h | >48h |

| 15b | >72h | >48h |

| 15c | >72h | >48h |

This would support the fact that PEG-HZ-PE conjugates containing hydrazone bond derived from the aliphatic aldehyde are more prone to hydrolytic degradation. Aromatic aldehyde-derived hydrazone bond is too stable for the purpose of pH-triggered drug release. Careful selection of an aldehyde and an acyl hydrazide would be necessary for the application of the hydrazone-based chemistry for the development of pH-sensitive pharmaceutical nanocarriers with required stabilities/instabilities at normal and acidic pH values. Additional studies on the synthesis of aromatic and aliphatic ketone-derived hydrazone-based PEG-PE conjugates are currently under way in our laboratory.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of acyl hydrazide activated PEG

Scheme 7.

SFB activation of phosphatidylethanolamine

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of PEG-HZ-PE conjugate

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 EB001961 to Vladimir P. Torchilin. Authors thank Vijay S. Boddapathi and Dr. Ganesh Thakur for the technical assistance with 1H NMR studies.

Footnote

- PE

Phosphotidylethanolamine

- DOPE

l,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- DPPE-SH

1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanolamine (sodium salt)

- PEG

methoxy(polyethylene)glycol

- HZ

hydrazone

References

- 1.Mainardes RM, Silva LP. Drug delivery systems: past, present, and future. Curr Drug Targets. 2004;5:449–455. doi: 10.2174/1389450043345407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishiyama N, Okazaki S, Cabral H, Miyamoto M, Kato Y, Sugiyama Y, Nishio K, Matsumura Y, Kataoka K. Novel cisplatin-incorporated polymeric micelles can eradicate solid tumors in mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8977–8983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreuter J. Drug targeting with nanoparticles. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1994;19:253–256. doi: 10.1007/BF03188928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storm G, Crommelin DJ. Colloidal systems for tumor targeting. Hybridoma. 1997;16:119–125. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1997.16.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simard P, Hoarau D, Khalid MN, Roux E, Leroux JC. Preparation and in vivo evaluation of PEGylated spherulite formulations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1715:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis GE, Delgado C, Fisher D, Malik F, Agrawal AK. Polyethylene glycol modification: relevance of improved methodology to tumour targeting. J Drug Target. 1996;3:321–340. doi: 10.3109/10611869608996824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maruyama K. In vivo targeting by liposomes. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:791–799. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong XB, Huang Y, Lu WL, Zhang X, Zhang H, Nagai T, Zhang Q. Intracellular delivery of doxorubicin with RGD-modified sterically stabilized liposomes for an improved antitumor efficacy: in vitro and in vivo. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94:1782–1793. doi: 10.1002/jps.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torchilin VP, Rammohan R, Weissig V, Levchenko TS. TAT peptide on the surface of liposomes affords their efficient intracellular delivery even at low temperature and in the presence of metabolic inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8786–8791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151247498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nori A, Kopecek J. Intracellular targeting of polymer-bound drugs for cancer chemotherapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:609–636. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayasundar R, Singh VP. In vivo temperature measurements in brain tumors using proton MR spectroscopy. Neurol India. 2002;50:436–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engin K, Leeper DB, Cater JR, Thistlethwaite AJ, Tupchong L, McFarlane JD. Extracellular pH distribution in human tumours. Int J Hyperthermia. 1995;11:211–216. doi: 10.3109/02656739509022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ojugo AS, McSheehy PM, McIntyre DJ, McCoy C, Stubbs M, Leach MO, Judson IR, Griffiths JR. Measurement of the extracellular pH of solid tumours in mice by magnetic resonance spectroscopy: a comparison of exogenous (19)F and (31)P probes. NMR Biomed. 1999;12:495–504. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199912)12:8<495::aid-nbm594>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khare AR, Peppas NA. Release behavior of bioactive agents from pH-sensitive hydrogels. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1993;4:275–289. doi: 10.1163/156856293x00564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braslawsky GR, Kadow K, Knipe J, McGoff K, Edson M, Kaneko T, Greenfield RS. Adriamycin(hydrazone)-antibody conjugates require internalization and intracellular acid hydrolysis for antitumor activity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1991;33:367–374. doi: 10.1007/BF01741596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo HS, Lee EA, Park TG. Doxorubicin-conjugated biodegradable polymeric micelles having acid-cleavable linkages. J Control Release. 2002;82:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee ES, Na K, Bae YH. Super pH-sensitive multifunctional polymeric micelle. Nano Lett. 2005;5:325–329. doi: 10.1021/nl0479987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen WC, Ryser HJ. cis-Aconityl spacer between daunomycin and macromolecular carriers: a model of pH-sensitive linkage releasing drug from a lysosomotropic conjugate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;102:1048–1054. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91644-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogden JR, Leung K, Kunda SA, Telander MW, Avner BP, Liao SK, Thurman GB, Oldham RK. Immunoconjugates of doxorubicin and murine antihuman breast carcinoma monoclonal antibodies prepared via an N-hydroxysuccinimide active ester intermediate of cis-aconityl-doxorubicin: preparation and in vitro cytotoxicity. Mol Biother. 1989;1:170–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel VF, Hardin JN, Mastro JM, Law KL, Zimmermann JL, Ehlhardt WJ, Woodland JM, Starling JJ. Novel acid labile COL1 trityl-linked difluoronucleoside immunoconjugates: synthesis, characterization, and biological activity. Bioconjugate Chem. 1996;7:497–510. doi: 10.1021/bc960038u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heffernan MJ, Murthy N. Polyketal nanoparticles: a new pH-sensitive biodegradable drug delivery vehicle. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:1340–1342. doi: 10.1021/bc050176w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillies ER, Frechet JM. pH-Responsive copolymer assemblies for controlled release of doxorubicin. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:361–368. doi: 10.1021/bc049851c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillies ER, Jonsson TB, Frechet JM. Stimuli-responsive supramolecular assemblies of linear-dendritic copolymers. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11936–11943. doi: 10.1021/ja0463738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gumusderelioglu M, Kesgin D. Release kinetics of bovine serum albumin from pH-sensitive poly(vinyl ether) based hydrogels. Int J Pharm. 2005;288:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin J, Shum P, Thompson DH. Acid-triggered release via dePEGylation of DOPE liposomes containing acid-labile vinyl ether PEG-lipids. J Control Release. 2003;91:187–200. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kratz F, Beyer U, Roth T, Schutte MT, Unold A, Fiebig HH, Unger C. Albumin conjugates of the anticancer drug chlorambucil: synthesis, characterization, and in vitro efficacy. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 1998;331:47–53. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-4184(199802)331:2<47::aid-ardp47>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beyer U, Roth T, Schumacher P, Maier G, Unold A, Frahm AW, Fiebig HH, Unger C, Kratz F. Synthesis and in vitro efficacy of transferrin conjugates of the anticancer drug chlorambucil. J Med Chem. 1998;41:2701–2708. doi: 10.1021/jm9704661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Stefano G, Lanza M, Kratz F, Merina L, Fiume L. A novel method for coupling doxorubicin to lactosaminated human albumin by an acid sensitive hydrazone bond: synthesis, characterization and preliminary biological properties of the conjugate. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2004;23:393–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toncheva V, Schacht E, Ng SY, Barr J, Heller J. Use of block copolymers of poly(ortho esters) and poly (ethylene glycol) micellar carriers as potential tumour targeting systems. J Drug Target. 2003;11:345–353. doi: 10.1080/10611860310001633839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oishi M, Nagasaki Y, Itaka K, Nishiyama N, Kataoka K. Lactosylated poly (ethylene glycol)-siRNA conjugate through acid-labile beta-thiopropionate linkage to construct pH-sensitive polyion complex micelles achieving enhanced gene silencing in hepatoma cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1624–1625. doi: 10.1021/ja044941d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steenbergen C, Deleeuw G, Rich T, Williamson JR. Effects of acidosis and ischemia on contractility and intracellular pH of rat heart. Circul Res. 1977;41:849–858. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.6.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frunder H. The pH changes of living tissue during activity and inflammation. Pharmazie. 1949;4:345–355. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellman I, Fuchs R, Helenius A. Acidification of the endocytic and exocytic pathways. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:663–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.003311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawant RM, Hurley JP, Salmaso S, Kale AA, Tolcheva E, Levchenko T, Torchilin VP. “Smart” Drug Delivery Systems: Double-targeted pH-responsive pharmaceutical nanocarriers. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:943–949. doi: 10.1021/bc060080h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rideout D. Self-assembling drugs: a new approach to biochemical modulation in cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Invest. 1994;12:189–202. doi: 10.3109/07357909409024874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lukyanov AN, Gao Z, Mazzola L, Torchilin VP. Polyethylene glycol-diacyllipid micelles demonstrate increased acculumation in subcutaneous tumors in mice. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1424–1429. doi: 10.1023/a:1020488012264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukyanov AN, Gao Z, Torchilin VP. Micelles from polyethylene glycol/phosphatidylethanolamine conjugates for tumor drug delivery. J Control Release. 2003;91:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00217-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Apelgren LD, Bailey DL, Briggs SL, Barton RL, Guttman-Carlisle D, Koppel GA, Nichols CL, Scott WL, Lindstrom TD, Baker AL, Bumol TF. Chemoimmunoconjugate development for ovarian carcinoma therapy: preclinical studies with vinca alkaloid-monoclonal antibody constructs. Bioconjugate Chem. 1993;4:121–126. doi: 10.1021/bc00020a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker MA, Gray BD, Ohlsson-Wilhelm BM, Carpenter DC, Muirhead KA. Zyn-Linked colchicines: Controlled-release lipophilic prodrugs with enhanced antitumor efficacy. J Control Release. 1996;40:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cordes EH, Jencks WP. The mechanism of hydrolysis of Schiff’s bases derived from aliphatic amines. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:2843–2848. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harnsberger HR, Cochran EL, Szmant HH. The basicity of hydrazones. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:5048–5050. [Google Scholar]