Abstract

Structure-reactivity relationships and substituent effects on carbocation stability in benzo[a] anthracene (BA) derivatives have been studied computationally at the B3LYP/6-31G* and MP2/6-31G** levels. Bay-region carbocations are formed by O-protonation of the 1,2-epoxides in barrierless processes. This process is energetically more favored as compared to carbocation generation via zwitterion formation/O-protonation, via single electron oxidation to generate a radical cation, or via benzylic hydroxylation. Relative carbocation stabilities were determined in the gas phase and in water as solvent (PCM method). Charge delocalization mode in the BA carbocation framework was deduced from NPA-derived changes in charges, and substitution by methyl or fluorine was studied at different positions selected on basis of the carbocation charge density. A bay-region methyl group produces structural distortion with consequent deviation from planarity of the aromatic system, which destabilizes the epoxide, favoring ring opening. Whereas fluorine substitution at sites bearing significant positive charge leads to carbocation stabilization by fluorine p-π back-bonding, a fluorine atom at a ring position which presented negative charge density leads to inductive destabilization. Methylated derivatives are less sensitive to substituent effects as compared to the fluorinated analogues. Although the solvent decreases the exothermicity of the epoxide ring opening reactions due to greater stabilization of the reactants, it provokes no changes in relative reactivities. Relative energies in the resulting bay-region carbocations are examined taking into account the available biological activity data on these compounds. In selected cases, quenching of bay-region carbocations was investigated by analyzing relative energies (in the gas phase and in water) and geometries of their guanine adducts formed via covalent bond formation with the exocyclic amino group and with the N-7.

Introduction

Mutagenic and/or carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)1 are widespread environmental pollutants (1). The main metabolic pathway for activation of these compounds involves formation of bay-region diol epoxides (DEs) (2). Benzylic carbocations generated from these electrophilic DEs by opening of the epoxide ring are capable of forming covalent adducts with the nucleophilic sites in DNA and RNA, leading to alteration of genetic material (3, 2). Adduct formation is accepted as a critical step in the mechanism by which PAHs can cause mutations resulting in induction of cancer (2).

The carcinogenic activity of polyarenes is frequently enhanced by methyl substitution at strategic positions. In this way, methyl substitution at a bay region tends to markedly increase the biological activity (4). Among benzo[a]anthracenes (BAs), the unsubstituted parent compound presents borderline activity (5), but 7-methylbenzo[a] anthracene (7-MBA) is considerably more active (it is the strongest tumor initiator among the twelve possible monomethylated BAs, followed by the 6-CH3, 8-CH3, and 12-CH3 derivatives) (6–9), while 7,12-dimethylbenzo[a]anthracene (7,12-DMBA) is one of the most potent carcinogens known (10). On the other hand, low tumorigenicity has been observed for 1-, 2-, 3- and 4-MBA (6). Among other dimethyl-BA compounds, the 6,8-dimethyl- and 8,9-dimethyl-BA have also been reported to have relatively high activity (4).

For 7,12-DMBA not only DE formation, but also the radical cation process (via one-electron oxidation) and benzylic sulfate ester formation (via initial formation of benzyl alcohol) could contribute to its metabolic activation (11). For the benzylic-DNA adducts, the 12-CH2OH and 7-CH2OH could both be involved in adduct formation (12).

Carcinogenic activity of PAHs is often strongly affected by fluorine substitution at strategic molecular sites (2,13). Whereas fluorine substitution at C-10 in 7-MBA and 7,12-DMBA led to markedly enhanced tumor initiating activity in mouse skin and mutagenic activity in human hepatoma (HepG2) cell-mediated assay (14–16), F-substitution at C-1, C-2, C-3, C-4, and C-5 resulted in lower bioactivity relative to 7,12-DMBA (15, 17–19). For other regioisomeric fluoro derivatives of 7,12-DMBA, there was no significant change in activity (14, 17). Similar F-substitution effects were also observed for the 7- and 12-monomethyl analogues of BA (16, 20–22). Effect of a fluoro substituent at C-9 and C-10 on tumorigenicity of 7-MBA-3,4-diol, 12-MBA-3,4-diol, and 7,12-DMBA-3,4-diol was also studied (21). It was argued that F-substitution at C-10 in BA increases the metabolic formation of the 3,4-diol, with no significant effect on the reactivity of the bay-region anti-DE (21). The 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-7,12-DMBA (THDMBA) is an animal carcinogen without an aromatic bay-region. Its 6-F-derivative is twice as potent as the parent compound, whereas the 5-F-derivative is inactive (19). Study of their metabolites indicated that benzylic hydroxylation at C1 and side chain hydroxylation at 12-Me are important in the metabolism of the reactive 6-F-derivative (23).

Very good agreement with the experimental reactivities of several PAH derivatives have been shown by recent quantum-mechanical calculations when applied to the study of the carcinogenic pathways of these compounds (24–28). Besides, modeling studies of biological electrophiles from PAHs by DFT methods have yielded appropriate descriptions of the NMR features and charge delocalization modes of their resulting carbocations (29–39).

In this work we have performed a model DFT study on the structural and electronic properties of the reactive intermediates of BA derivatives, starting with the bay-region epoxides. As in previous computational studies (24–28), these intermediates have proven to generate the same reactivity trends as their DE analogs, while requiring considerably less computational time. The present study was inspired by our earlier stable ion work on the BA carbocations (31) and sets the stage for a more comprehensive structure/reactivity study with a larger set of regioisomeric mono- and dialkylated BAs. Fluoro and methyl substitution at selected molecular sites was investigated. Changes in energy for epoxide ring opening reactions were calculated in gas phase and in water as solvent. Charge delocalization modes (positive charge density distribution) in the resulting carbocations were evaluated by means of the NPA-derived changes in charges (carbocation minus neutral).

To model the crucial step of covalent adduct formation, adducts resulting from quenching of selected carbocations (derived from their corresponding epoxides) with guanine via the exocyclic amino group and via the N-7 were computed, and their geometrical features and relative energies were compared.

Computational methods

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed with the Gaussian 03 package (40), employing the B3LYP (41–43) functional and the 6-31G* split-valence shell basis set. Geometries were fully optimized and minima were characterized by calculation of the harmonic vibrational frequencies. Natural bond orbital population analysis (NPA) was evaluated by means of the NBO program (44). The solvent effect was estimated by the polarized continuum model (PCM) (45–48) without geometry optimizations unless specified. Zero-point energy (ZPE) corrections were included for gas-phase results. MP2 single point energy calculations were performed with the 6-311G** basis set starting with the B3LYP/6-31G* optimized geometries (MP2/6-311G**//B3LYP/6-31G*). AMI semiempirical calculations (49) were utilized for initial conformational searches in the covalent adducts and the most favored conformations were selected for energy calculations by DFT.

Results and Discussion

Mechanistic studies on the hydrolysis of benzo[a]pyrene-DE demonstrated pH dependency and catalysis by DNA and by polynucleotides, showing that protonation must occur before or during the rate determining step (50, 51). Based on these studies, it was proposed that a physically-bound DE reacts to form a physically bound benzylic carbocation in the rate determining step. The monohydrogen phosphate group on the nucleotide acts as general acid, and stacking interactions between the PAH-DE and the base contribute to catalysis. Moreover, it is likely that electrophilic attack of DNA nucleotides by PAH epoxides is SN1-like and proceeds through proton-stabilized transition states in which the hydrocarbon exhibits significant carbocationic character (52–54). Taking this into account, formation of the benzylic carbocation derived from BA-1,2-epoxide was calculated by means of two possible pathways: by epoxide ring opening of the O-protonated species, and via a mechanism involving zwitterion formation by heterolytic opening of the neutral epoxide and subsequent protonation (Figure 1). Comparison of the changes in energy for both paths served as a test for selecting only the most likely process for the entire study. The same calculations were performed for 12-MBA in order to account for the presence of a bay-region methyl group.

Figure 1.

Alternative mechanistic pathways for activation of benzo[a]anthracene-1,2-epoxide and 12-methyl-benzo[a]anthracene-1,2-epoxide (aqueous-phase values in parenthesis).

For both zwitterion calculations the position of the hydrogen atom attached to C-2 could not be fully optimized because, if its bond length to C-2 was not constrained, it migrated spontaneously to generate the more stable 2-keto compound. Conversely, the corresponding protonated epoxides, i.e., the oxonium ions, could not be located as minima on the potential energy surface, as in both cases the epoxide ring opened by a barrierless process upon O-protonation. Zwitterion formation was endothermic by ca. 40 kcal/mol, while both protonation steps were highly exothermic. Consequently, the protonated epoxide -> carbocation pathway was selected for computations involving the rest of the compounds in the present study, since it was established as the most favored mechanism.

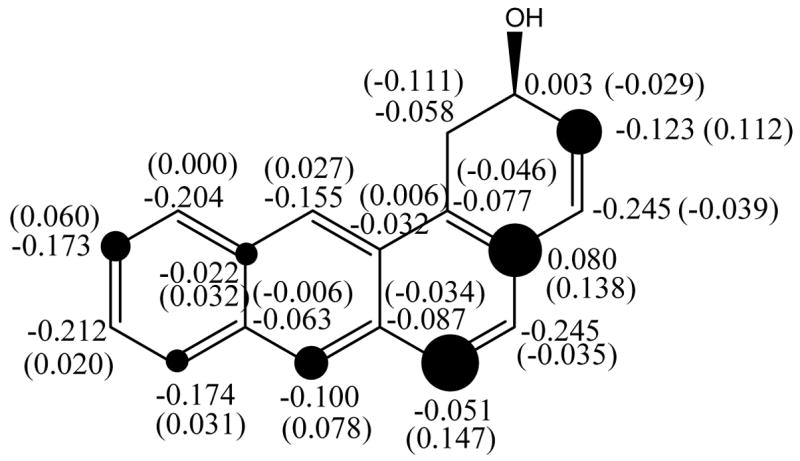

The charge delocalization map for BA is shown in Figure 2. According to the NPA-derived charge distribution, positive charge in the resulting carbocation is delocalized throughout the π-system. Earlier stable ion NMR studies have shown that arenium ions and benzylic carbocations derived from BA exhibit strong anthracenium ion character (31).

Figure 2.

Computed gas-phase NPA heavy atom charge densities (Δcharges relative to the neutral compound in parentheses) for the carbocation generated from BA-1,2-epoxide. [Dark circles are roughly proportional to the magnitude of C Δcharges; threshold was set to 0.030].

Regarding the charge delocalization mode for BA, substitution at positions 6 and 3 of the 1,2-epoxide would be expected to produce the most noticeable effects, followed by positions 7 and 10. On the other hand, substitution at positions 4 and 5 would present the strongest effects in the opposite sense, as these sites develop negative charge density upon carbocation formation. Bearing this in mind, calculations for the protonated-epoxide opening reaction (reaction 1 type) were carried out for eight monomethylated derivatives of BA-1,2-epoxide.

(1).

Positions 4 and 3 were left unsubstituted since these sites give rise to the 3,4-diol, which is then epoxidized to the bay-region DE, in line with the low tumorigenicity caused by methyl substitution at the 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-positions (6). The dimethylated compound 7,12-DMBA was also considered. Calculation results are collected in Table 1. Changes in NPA-derived charges are included for the carbocation centre and the methyl group (carbon plus attached-hydrogen charges). It should be noticed that the same observation regarding the instability of the oxonium ion was made for every protonated epoxide in the present study.

Table 1.

Calculations for the Methylated Derivatives of BA-1,2-Epoxide

| Methylated position | ΔEr (kcal/mol)

|

Δqa | ΔqC-1b | ΔqCH3c | Carcinogenic activityd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP/6-31G*

|

MP2/6-311G**e |

|||||

| Gas phasef (Aqueous phase)g | Gas phase | |||||

| 7,12 | −238.09 (−170.90) | −233.78 | −0.102 | 0.045 (7-Me)

0.024 (12-Me) |

Very potent | |

| 7 | −235.01 (−168.95) | −230.92 | 0.078 | −0.088 | 0.042 | Potent |

| 12 | −236.12 (−170.47) | −232.34 | 0.027 | −0.096 | 0.022 | Moderately active |

| 6 | −235.81 (−169.18) | −232.05 | 0.147 | −0.059 | 0.059 | Moderately active |

| 8 | −234.46 (−168.77) | −230.35 | 0.031 | −0.085 | 0.032 | Moderately active |

| 10 | −235.27 (−169.21) | −231.16 | 0.060 | −0.086 | 0.041 | Weakly active |

| 9 | −235.27 (−168.84) | −231.86 | 0.020 | −0.084 | 0.035 | Weakly active |

| 5 | −234.41 (−168.42) | −231.28 | -0.035 | −0.086 | 0.041 | Weakly active |

| 11 | −233.87 (−168.28) | −230.26 | 0.000 | −0.084 | 0.025 | Weakly active |

| BA | −233.29 (−168.72) | −229.63 | - | −0.081 | - | Weakly active |

Change in charge density for the indicated carbon atom in the nonmethylated compound (qCcarbocation – qCepoxide).

Change in charge density at the carbocation center, between the open carbocation and the neutral closed epoxide (qC-1carbocation – qC-1epoxide).

Change in charge density between the open carbocation and the neutral closed epoxide (qCH3carbocation – qCH3epoxide).

As compiled in (55).

Single-point energy calculation.

ZPE correction included.

PCM optimizations.

The ΔEr for the opening reactions could be viewed as a measure of the stability of the resulting carbocations. In relation to this, good correlations have been obtained between the calculated relative energies for carbocation formation from various PAHs and their reactivity towards nucleic acid (24–28). Moreover, a clear relationship was observed between the extent of charge delocalization in the carbocation (assessed by the decrease in positive charge at the carbocationic centre within series of compounds) and the ease of its formation (24–26).

The present calculated results in Table 1 show a general agreement with the known carcinogenic activities of the BA series, even though differences in energy are small. It should be noted that no clear correlation had been observed between mutagenicity and carcinogenic potency for BA, 7,12-DMBA, and the twelve isomeric MBAs (55). In this way, while 7,12-DMBA was the most potent mutagen, followed by 7-MBA, the moderately strong and weak carcinogens were not distinguishable by their bacterial mutagenicity, which differed depending on the experimental conditions (55). Nevertheless, these theoretical computations follow the carcinogenic trend of this type of compounds fairly well, given that no conclusive experimental activity order is available, and considering that in the calculations the biological environment effects (in particular differences in DNA repair) are not taken into account. Thus, according to ΔEr, carbocation formation from 7,12-DMBA is the most favored reaction. The isomeric monomethylated derivatives all exhibited similar ΔEr values, with 12- and 6-MBA being among the most reactive ones, while 11- and 5-MBA corresponded to the least exothermic reactions, as it was expected. Among the monomethyl epoxides, 12-MBA yielded the most favorable ΔEr. Since parent BA was least reactive in the series, methyl substitution resulted in stabilization of the carbocations. As no significant hyperconjugative effects were assessed according to NBO analysis (no depletion of the C-H bonds of the methyl group), these observations indicate that the methyl group causes inductive stabilization. The MP2/6-311G** energies showed the same reactivity tendencies as the B3LYP results.

12-MBA and 7,12-DMBA, i.e., both bay-region methylated compounds, present a deviation from planarity of the aromatic system at the bay region due to steric strain induced by the methyl group. The enhanced carcinogenic activity induced by methyl substitution at the bay region has been explained by a more favored opening of the epoxide ring (24). This fact stems from instability of the ring closed species, which presents a distorted non-planar structure (56), rather than from stabilization of the open carbocation by methyl substitution.

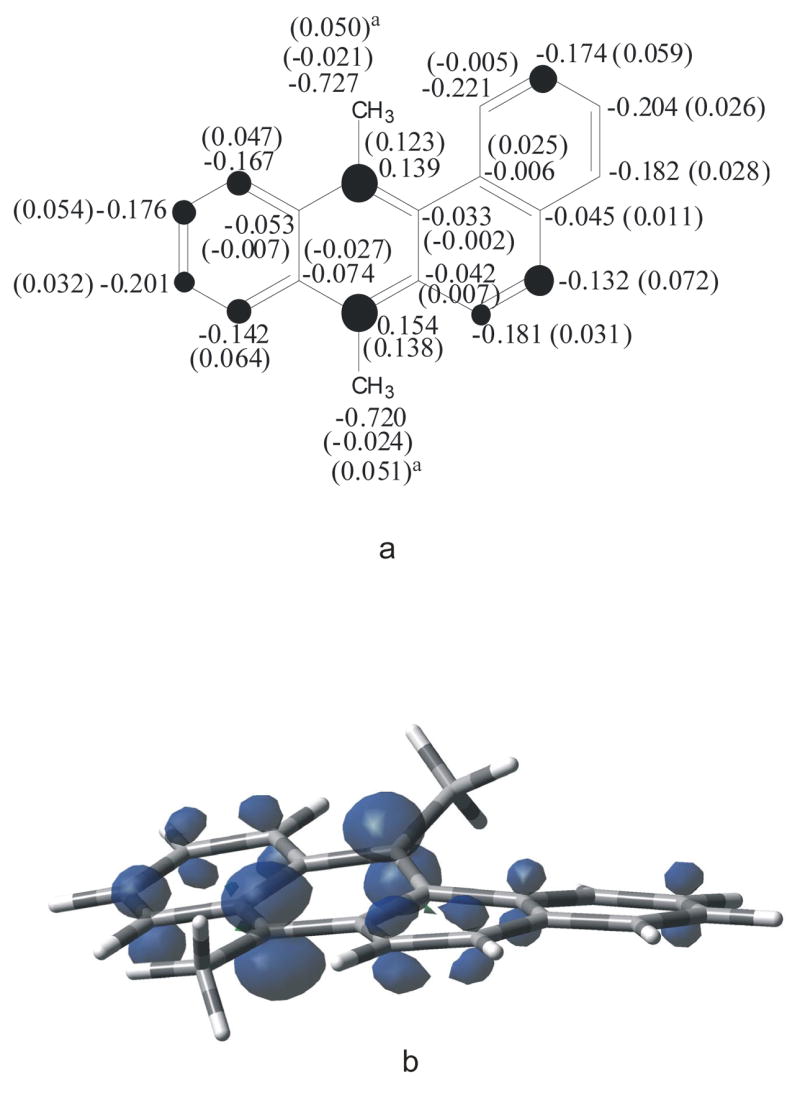

Another major activation pathway that has been invoked in metabolism of 7,12-DMBA is the radical cation (RC) mechanism (57–60). This was taken into account in the present study by considering the formation of the RC of 7,12-DMBA (reaction 2). This species presented both charge and spin densities mainly located at C-7 and C-12 (Figure 3), with negligible hyperconjugative stabilization by the methyl substituents.

Figure 3.

7,12-DMBA radical cation; (a) computed gas-phase NPA heavy atom charge densities (Δcharges relative to the neutral compound in parentheses; acarbon plus hydrogens); [Dark circles are roughly proportional to the magnitude of C Δcharges; threshold was set to 0.030]; (b) spin density.

(2).

Additionally, the meso-region theory proposes the formation of meso-hydroxymethyl metabolites, which subsequently generate benzylic-DNA adducts (61–65). In case of 7–12-DMBA, involvement of the 12-CH2OH and 7-CH2OH have been invoked in adduct formation via this pathway, with hydroxylation suggested as the rate-limiting step (72). Accordingly, formation of the 7-CH2+ and 12-CH2+ carbocations from their corresponding alcohols were calculated in order to take into consideration this metabolic mechanism (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Generation of benzylic 7-CH2+ and 12-CH2+ carbocations from 7,12-DMBA (aqueous-phase values in parenthesis).

Hence, the change in energy for reaction 2 and for the hydroxymethyl paths in Fig. 4 was analyzed and compared with the thermodynamics of the epoxidation process (reaction 3).

(3).

With this approach, ΔEr for reaction 2 was 149.49 kcal/mol (115.33 kcal/mol in water as solvent). On the other hand, hydroxylation followed by formation of the 7-CH2+ and 12-CH2+ carbocations were exothermic by ca. −87 kcal/mol (−94 kcal/mol in water) and −218 kcal/mol (−146 kcal/mol), respectively. Moreover, in the framework of the meso-region theory, one-electron oxidation of 7,12-DMBA coupled with oxygen transfer has been reported to yield both 7- and 12-hydroxymethyl isomers (66), which determines that primary benzylic alcohol formation would also be dependent on the energetic of reaction 2. For reaction 3, ΔEr was −58.30 kcal/mol (−62.19 kcal/mol in water), with subsequent epoxide opening reaction 1 for 7,12-DMBA-1,2-epoxide being highly exothermic (−238.09 kcal/mol, −170.64 kcal/mol in water). Therefore, these computations point to the DE mechanism as the energetically more favored metabolic path for 7,12-DMBA.

Turning our attention to the fluorinated analogs, calculations were carried out for the 5-, 6-, 9-, 10- and 12-fluorinated derivatives of 7-MBA. Fluorination at C-12 was analyzed in order to reveal any influence that may be exerted by the fluorine atom when located in a bay region, and the 7-FBA was considered for comparison with 7-MBA. Results are gathered in Table 2.

Table 2.

Calculations for the Fluorinated Derivatives of 7-MBA-1,2-Epoxide

| Fluorinated position | ΔEr (kcal/mol)

|

Δqa | ΔqC-1b | ΔqFc | C-F bond length (Angstroms) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP/6-31G*

|

MP2/6-311G**d |

|||||

| Gas phasee (Aqueous phase) | Gas phase | |||||

| 6 | −235.94 (−170.02) | −232.20 | 0.147 | −0.093 | 0.051 | 1.3261 |

| 12 | −235.58 (−168.84) | −231.42 | 0.027 | −0.086 | 0.018 | 1.3485f |

| 10 | −233.90 (−168.25) | −229.18 | 0.060 | −0.086 | 0.033 | 1.3324 |

| 9 | −232.72 (−167.62) | −228.80 | 0.020 | −0.084 | 0.027 | 1.3365 |

| 5 | −230.53 (−164.21) | −225.96 | −0.035 | −0.063 | 0.026 | 1.3413 |

| 7-F-BA | −231.94 (−167.20) | −227.67 | 0.078 | −0.086 | 0.033 | 1.3360 |

Change in charge density for the indicated carbon atom in BA (qCcarbocation - qCepoxide).

Change in charge density at the carbocation center, between the open carbocation and the neutral closed epoxide (qC-1carbocation – qC-1epoxide).

Change in charge density between the open carbocation and the neutral closed epoxide (qFcarbocation – qFepoxide).

Single-point energy calculation.

ZPE correction included.

The fluorine atom forms a hydrogen-bond interaction.

By taking into account the ΔErS for epoxide ring opening of the fluorinated compounds, it is noted that the 6-F structure is most favored for opening of the 1,2-epoxide, yielding a ΔEr even more exothermic than the unsubstituted molecule. Hence, a fluorine atom at a highly positively charged site stabilizes the carbocation. The 10-F derivative was less reactive than nonfluorinated 7-MBA, this fact being in contrast with the experimental tumorigenic activities. However, subsequent studies have suggested that the influence of fluorine at C-10 of BA is not due to increased reactivity of the bay-region DE but rather likely on the initial formation of the 3,4-diol (21). Both 10-F-7-MBA and 7-MBA afforded ΔErs more exothermic than 9-F-7-MBA, in accord with the biological activity of these derivatives (16, 20–22). On the other hand, F-substitution at a position with negative charge density (C-5) decreased the exothermicity of the opening reaction, while 7-FBA also gave a less favored value than 7-MBA, both results being in agreement with their reported relative tumorigenicities (23, 22).

In addition, a correlation was found between exothermicity of the epoxide ring opening and the C-F bond length, in the sense that the C-F bond becomes shorter with increasing stability of the carbocation. This observation corresponds to electron density loss at F, assessed by NPA-derived charges. Hence, fluorine stabilization of the PAH carbocation correlates with the degree of fluoronium ion character, which overrides the unfavorable inductive electron withdrawal of F. Fluorine substitution was previously seen to have a major impact on the charge distribution of PAH carbocations (67, 68) and dications (68). The exception to the observations made above was the 12-F compound. In this case a hydrogen bond interaction takes place between fluorine and the hydrogen atom attached to C-1. This interaction is stronger in the open carbocation (H-F distance is 2.0376 Å in the carbocation vs. 2.0633 Å in the epoxide), thus favoring epoxide ring opening, which agrees with the reported activity (22). In general, larger variations in ΔEr among the different fluoro analogues were observed, indicating that fluoronium ion character has a stronger influence than the inductive effect exerted by the methyl group in the methylated derivatives.

Aqueous-phase calculations (PCM method with water as solvent) afforded the same reactivity patterns as those in the gas phase, when comparing any given series of compounds/reactions, i.e., inclusion of the solvent did not alter the relative reactivity trends. However, despite the greater stabilization of the carbocations as compared to the neutral epoxides, the ring opening reactions were less exothermic in water owing to the large solvation energy of proton.

Guanine covalent adducts

It has been established that bay-region DEs derived from PAHs predominantly form stable adducts with DNA by cis or trans addition of the exocyclic amino groups of deoxyguanosine and deoxyadenosine (69). Moreover, depurinating products that are lost from DNA by cleavage of the glycosidic bond are formed by reaction with the N-7 of guanine, and at N-3 and N-7 of adenine (70). Bearing this in mind, the adducts arising from reactions with the exocyclic nitrogen and with the N-7 of guanine were calculated for the carbocations derived from 7,12-DMBA-1,2-epoxide and 12-F-7-MBA-1,2-epoxide. 7,12-DMBA was selected considering its strong carcinogenic potency, and the 12-F derivative was chosen as model to examine the influence of a bay-region fluorine atom. The major 7,12-DMBA adduct formed in vivo corresponds to the one derived from the anti-DE with deoxyguanosine (71). The trans products were considered, this mode of attack being preferred for anti-DEs (72). Conformational searches by rotation of the generated C-N bond were performed by AM1 calculations in order to find the most stable rotamer for each compound. These lowest energy structures were subsequently selected for optimization by DFT calculations (Table 3, Figures 5 and 6). Superimposed structures are shown in Figure 7.

Table 3.

Calculations for Adducts of 12-Substituted-7-MBA-1,2-Epoxide with Guanine

| Carbocation | Reacting Nitrogen of Guanine | Total Energy (hartree) | Relative Energy (kcal/mol) | ΔEreaction (kcal/mol)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas phase | Aqueous phase | Gas phaseb | Aqueous phase | Gas phaseb | Aqueous phase | ||

| 12-CH3 | Exocyclic | −1389.52582 | −1389.57655 | 1.13 | 0.00 | 222.81 | 155.04 |

| N-7 | −1389.52800 | −1389.57260 | 0.00 | 2.48 | 221.68 | 157.52 | |

| Exocyclic6 | −1313.13108 | −1313.17085 | - | - | 220.80 | 153.73 | |

| 12-F | Exocyclic | −1449.45704 | −1449.50303 | 1.58 | 2.21 | 218.78 | 154.60 |

| (−1449.50846)d | (0.12) | ||||||

| N-7 | −1449.45912 | −1449.50655 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 217.20 | 152.39 | |

| (−1449.50865)d | (0.00) | ||||||

ΔEreaction = EnergyAdduct + EnergyH+ − EnergyGuanine − EnergyCarbocation.

ZPE correction included.

Adduct from 7,12-DMBA.

PCM optimization.

Figure 5.

Adducts formed between guanine and 7,12-DMBA-1,2-epoxide; (a) exocyclic N; (b) N-7 isomer.

Figure 6.

Adducts formed between guanine and 12-F-7-MBA-1,2-epoxide; (a) exocyclic N; (b) N-7 isomer.

Figure 7.

Superimposed structures of the adducts of 7,12-DMBA-1,2-epoxide and 12-F-7-MBA-1,2-epoxide with guanine; (a) exocyclic N-adduct; (b) N-7 adduct.

For 7,12-DMBA-1,2-epoxide, a perpendicular arrangement between the two aromatic moieties was the most favored disposition for both adducts. A noteworthy feature in this adduct is deviation from planarity in the system which is caused by steric interaction between guanine and the 12-Me group. According to the gas-phase calculations, the most stable isomer was the N-7 product, ca. 1 kcal/mol lower in energy than the exocyclic adduct. This fact is probably due to the stabilization brought about by two intramolecular hydrogen bonds in the N-7 product (between the guanine carbonyl oxygen, the bay-region hydrogen, and one of the 12-Me hydrogens), vs. one hydrogen bond in the exocyclic adduct. However, aqueous-phase energy computations reverses the relative stability of these adducts, with the exocyclic one becoming more stable by over 2 kcal/mol.

In the case of 12-F-7-MBA-1,2-epoxide, calculations in the gas phase showed that the N-7 adduct is once again more favored (by about 1 kcal/mol), with one hydrogen-bond interaction being attained between the guanine carbonyl and the bay-region hydrogen. In the exocyclic adduct, the aromatic moieties lose coplanarity in order to form a hydrogen bond between the fluorine and the hydrogen atom attached to N-1. Interestingly, computations in water (both single points and optimizations) afforded almost the same energy for both adducts, suggesting the formation of near equal amounts of the exocyclic and N-7 adducts.

Reaction energies for the formation of each type of adduct with both carbocations (measured as the energy difference between the adduct plus proton, minus guanine and carbocation total energies) were comparable, although slightly more favored for 12-F-7-MBA-1,2-epoxide. Hence, the presence of a fluorine atom at the bay region seems to increase reactivity as compared to methyl substitution at the same position. Inclusion of the solvent led to a decrease in the endothermicity of the reactions as a result of better proton solvation.

Benzylic 12-CH2-adducts from 7,12-DMBA are originated by both the RC and meso-region pathways. In order to compare their relative stabilities with those derived from the DE path, the 12-CH2-exocyclic adduct was computed. Calculations afforded a ΔEr for formation comparable with those found for the adducts from 7,12-DMBA-1,2-epoxide (Table 3). According to these results, the relative amounts of adducts arising from covalent binding to DNA by means of alternative metabolic mechanisms would be primarily determined by the plausibility of generation of the respective ultimate electrophilic PAH metabolites.

Concluding remarks

According to the present DFT study, stability of the carbocations generated from oxidized metabolites of B A seems to correlate with the available data on their biological activity. Calculations in this work point to the DE mechanism as the main metabolic activation pathway for BA and its methylated and fluorinated derivatives. Epoxide protonation/ring opening is strongly preferred over zwitterion formation/protonation. The MP2/6-311G** relative reactivities agreeded with the B3LYP/6-31G* results.

Methylated compounds exhibit more exothermic ΔErS than the nonmethylated analogue, although very similar values were obtained for the methylated series. As NBO analysis did not reveal significant hyperconjugation effects, it is inferred that methyl substitution stabilizes the carbocations mainly by donor inductive effect. The neutral epoxide presented deviation from planarity in the aromatic system when a methyl group is substituted at C-12. Therefore, enhanced carcinogenic activity caused by methyl substitution at the bay region is explained by preferential opening of the epoxide ring due to higher energy of the more crowded epoxide.

A fluorine atom at a highly positive charged site stabilizes the carbocations by p-π back-bonding and development of fluoronium ion character, which overrides the inductive electron withdrawal of F. Correlation between stability of the generated carbocation and the loss in electron density at F corresponds with shortening of the C-F bond length. Among the fluorinated compounds, the 6-F structure is best for opening of the 1,2-epoxide, affording a ΔEr more exothermic than the nonfluoro structure. On the other hand, F-substitution at a position bearing negative charge density decreases the exothermicity of the ring opening reaction. In the case of the 12-F compound a hydrogen bond interaction takes place between fluorine and the hydrogen atom attached to C-1. This interaction assists the ring opening reaction as it is stronger in the open carbocation than in the epoxide. In general, fluorine exerted a stronger influence than methyl, as F-substitution at different sites generated larger variations in the ring opening reaction energy as compared to the methylated compounds.

Aqueous-phase calculations yielded the same reactivity as gas-phase computations, although epoxide ring opening was less exothermic in water because of the large solvation energy of the reactants. The change in the preferred product of the addition reactions with guanine due to solvent effect is noteworthy for 7,12-DMBA-1,2-epoxide. Whereas the N-7 adduct was most stable in gas phase, in water as solvent the most stable adduct was the one formed by reaction with the exocyclic nitrogen of guanine, in accordance with experimental observations, suggesting that DFT studies on the reactivity of this type of compounds could provide reasonable estimates when extrapolated to living organisms. On the other hand, for the less studied 12-F-7-MBA derivative, the present study points to the formation of both type of guanine adducts in near equal amounts. This finding must awaits further experimental verification.

Supplementary Material

Cartesian coordinates of all optimized structures presented in this work. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

this investigation was supported in part by the NCI of NIH (2R15-CA078235-02A1). G.L.B gratefully acknowledges financial support from CONICET and the Secretaria de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Secyt).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: PAH, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon; DE, diol epoxide; BA, benzo[a] anthracene; 7-MBA, 7 -methylbenzo [a] anthracene; 7,12-DMBA, 7,12-dimethylbenzo[a] anthracene; DFT, density functional theory; NPA, natural population analysis; NBO, natural bonding orbital; PCM, polarized continuum model; RC, radical cation; ZPE, zero-point energy; MP2, second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks of Chemicals to Humans, Vol. 32: Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, Part 1, Chemical, Environmental and Experimental Data. IARC; Lyon: 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey RG. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: chemistry and carcinogenicity. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fetzer SM, Huang C-R, Harvey RG, LeBreton PR. Photoelectron and ab initio molecular orbital investigations of genotoxic benz[a] anthracene metabolites: electronic influences on DNA binding. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:2385–2394. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecht SS, Melikian AA, Amin S. Effect of methyl substitution on the tumorigenicity and metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In: Yang SK, Silverman BD, editors. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Carcinogenesis: Structure-Activity Relationships. Vol. 1. CRS Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1988. pp. 95–128. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood AW, Levin W, Chang RL, Lehr RE, Schaefer-Ridder M, Karle JM, Jerina DM, Conney AH. Tumorigenicity of five dihydrodiols of benz[a]anthracene on mouse skin: exceptional activity of benz[a]anthracene-3,4-diol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:3176–3179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wislocki PG, Fiorentini KM, Fu PP, Yang SK, Lu AY. Tumor-initiating ability of the twelve monomethylbenz [a] anthracenes. Carcinogenesis. 1982;3:215–217. doi: 10.1093/carcin/3.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pataki J, Huggins C. Molecular site of substituents of benz[a]anthracene related to carcinogenicity. Cancer Res. 1969;29:506–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugiyama T. Chromosomal aberrations and carcinogenesis by various benz[a] anthracene derivatives. Gann. 1973;64:637–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huggins CB, Pataki J, Harvey RG. Geometry of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:2253–2260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.6.2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dipple A, Moschel RC, Bigger CAH. Polynuclear aromatic carcinogens. In: Searle CE, editor. Chemical Carcinogens. Vol. 1. ACS Monograph 182, American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1984. pp. 41–163. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xue W, Warshawsky D. Metabolic activation of polycyclic and heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and DNA damage: a review. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;206:73–93. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar MNVR, Vadhanam MV, Horn J, Flesher JW, Gupta RC. Formation of benzylic-DNA adducts resulting from 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene in vivo. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:686–691. doi: 10.1021/tx049686p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hecht SS, Amin S, Melikian AA, La Voie EJ, Hoffman D. Effect of methyl and fluorine substitution on the metabolic activation and tumorigenicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In: Harvey RG, editor. Polycyclic Hydrocarbons and Carcinogenesis, ACS Symposium Series 283, ch. 2. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1985. pp. 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiGiovanni J, Decina PC, Diamond L. Tumor-initiating activity of 9- and 10-fluoro-7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) and the effect of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on tumor-initiation by monofluoro derivatives of DMBA in SENCAR mice. Carcinogenesis. 1983;4:1045–1049. doi: 10.1093/carcin/4.8.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond L, Cherian K, Harvey RG, DiGiovanni J. Mutagenic activity of methyl- and fluoro-substituted derivatives of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a human hepatoma (HepG2) cell-mediated assay. Mutat Res. 1984;136:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(84)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawyer TW, Fisher EP, DiGiovanni J. Skin tumor-initiating activities of 9- and 10-fluoro derivatives of 7- or 12-methylbenz[a]anthracene in SENCAR mice. Carcinogenesis. 1987;8:1465–1468. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.10.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey RG, Dunne FB. Multiple regions of metabolic activation of carcinogenic hydrocarbons. Nature. 1978;273:566–568. doi: 10.1038/273566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiGiovanni J, Diamond L, Singer JM, Daniel FB, Witiak DT, Slaga TJ. Tumor-initiating activity of 4-fluoro-7,12-dimethylbenz[a] anthracene and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-7,12-dimethylbenz[a] anthracene in female SENCAR mice. Carcinogenesis. 1982;3:651–655. doi: 10.1093/carcin/3.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Black SD, Sharma PK, Gallucci JC, Blackburn AC, Downs JW, Rinderle SJ, Witiak DT. Modulation of carcinogenicity in 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (THDMBA) by fluorine substitution: crystal structures of 5- and 6-fluoro regioisomers. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:1337–1343. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.8.1337. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey RG, Cortez C. Fluorine-substituted derivatives of the carcinogenic dihydrodiol and diol epoxide metabolites of 7-methyl-, 12-methyl-and 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:7101–7118. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baer-Dubowska W, Nair RV, Dubowski A, Harvey RG, Cortez C, DiGiovanni J. The effect of fluoro substituents on reactivity of 7-methylbenz[a]anthracene diol epoxides. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:722–728. doi: 10.1021/tx950207j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood AW, Levin W, Chang RL, Conney AH, Slaga TJ, O’Malley RF, Newman MS, Buhler DR, Jerina DM. Mouse skin tumor-initiating activity of 5-, 7-, and 12-methyl and fluorine-substituted benz[a] anthracenes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1982;69:725–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinderle SJ, Black SD, Sharma PK, Witiak DT. Comparative metabolism in vitro of a novel carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene, and its two regioisomeric firing fluoro analogs. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3035–3042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borosky GL. Theoretical study related to the carcinogenic activity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J Org Chem. 1999;64:7738–7744. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borosky GL. Calculations related to the reactivity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon episulfides. Helv Chim Acta. 2001;84:3588–3599. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borosky GL. Theoretical study concerning the reativity of imine derivatives of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:601–608. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borosky GL, Laali KK. Theoretical study of aza-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (aza-PAHs), modelling carbocations from oxidized metabolites and their covalent adducts with representative nucleophiles. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:1180–1188. doi: 10.1039/b416429f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borosky GL, Laali KK. A computational study of carbocations from oxidized metabolites of dibenzo[a,h]acridine and their fluorinated and methylated derivatives. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1876–1886. doi: 10.1021/tx0501841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okazaki T, Laali KK, Zajc B, Lakshman MK, Kumar S, Baird WM, Dashwood W-M. Stable ion study of benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) derivatives: 7,8-dihydro-BaP, 9,10-dihydro-BaP and its 6-halo derivatives, 1- and 3-methoxy-9,10-dihydro- BaP-7(8H)-one, as well as the proximate carcinogen BaP 7,8-dihydrodiol and its dibenzoate, combined with a comparative DNA binding study of regioisomeric (1-, 4-, 2-) pyrenylcarbinols. Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:1509–1516. doi: 10.1039/b212412b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laali KK, Hansen PE. Charge delocalization pathways in persistent 1-pyrenyl-, 4-pyrenyl-, and 2-pyrenylmethylcarbenium ions as models of PAH-epoxide ring opening: NMR studies in superacids and AM1 calculations. J Org Chem. 1997;62:5804–5810. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laali KK, Tanaka M. Charge delocalization in persistent benz[a]anthracenium cations BAH+ and related α-carbocations/carboxonium ions: modeling epoxide ring opening in potent carcinogens. J Org Chem. 1998;63:7280–7285. doi: 10.1021/jo980722x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laali KK, Okazaki T, Kumar S, Galembeck SE. Substituent effects and charge delocalization mode in chrysenium, benzo[c]phenanthrenium, and benzo[g]chrysenium cations: a stable ion and electrophilic substitution study. J Org Chem. 2001;66:780–788. doi: 10.1021/jo001268b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laali KK, Okazaki T, Harvey RG. First examples of stable arenium ions from large methylene-bridged polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Directive effects and charge delocalization mode. J Org Chem. 2001;66:3977–3983. doi: 10.1021/jo0100603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laali KK, Okazaki T, Hansen PE. Stable ion study of regioisomeric carboxonium-substituted pyrenium ions: directive effects, charge delocalization mode, and conformational aspects. J Org Chem. 2000;65:3816–3828. doi: 10.1021/jo0001939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laali KK, Okazaki T, Coombs MM. Persistent carbocations from bay region methoxy-substituted cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene and its derivatives. A structure/reactivity study. J Org Chem. 2000;65:7399–7405. doi: 10.1021/jo000534i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Review: Laali KK, Okazaki T. Review: NMR of persistent carbocations from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) Annu Rep NMR Spectrosc. 2002;47:149–214.

- 37.Laali KK. Stable ion chemistry of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs); modeling electrophiles from carcinogens, chap. 9. In: Olah GA, Prakash GKS, editors. Carbocation Chemistry. Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okazaki T, Laali KK. A theoretical (DFT, GIAO-NMR, NICS) study of the carbocations and oxidation dications from azulenes, homoazulene, benzazulenes, benzohomoazulenes, and the isomeric azulenoazulenes. Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:3078–3093. doi: 10.1039/b303865c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okazaki T, Laali KK. Carbocations (M + H)+ and oxidation dications (M2+) from benzo[a]pyrene and its nonalternant isomers azulenophenalenes: a theoretical (DFT, GIAO, NICS) study. J Org Chem. 2004;69:510–516. doi: 10.1021/jo035133s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03, Revision B.05. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford, CT: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry. III The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Physical Review B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miehlich B, Savin A, Stoll H, Preuss H. Results obtained with the correlation energy density functional of Becke and Lee, Yang and Parr. Chem Phys Lett. 1989;157:200–206. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glendening ED, Reed AE, Carpenter JE, Weinhold F. NBO Version 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cancès MT, Mennucci V, Tomasi J. A new integral equation formalism for the polarizable continuum model: theoretical background and applications to isotropic and anisotropic dielectrics. J Chem Phys. 1997;107:3032–3041. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mennucci B, Tomasi J. Continuum solvation models: a new approach to the problem of solute’s charge distribution and cavity boundaries. J Chem Phys. 1997;106:5151–5158. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mennucci B, Cancès E, Tomasi J. Evaluation of solvent effects in isotropic and anisotropic dielectrics and in ionic solutions with a unified integral equation method: theoretical bases, computational implementation, and numerical applications. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:10506–10517. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomasi J, Mennucci B, Cancès E. The IEF version of the PCM solvation method: an overview of a new method addressed to study molecular solutes at the QM ab initio level. J Mol Struct (Theochem) 1999;464:211–226. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dewar MJS, Zoebisch EG, Healy ER, Stewart JJP. Development and use of quantum mechanical molecular models. 76 AM1: a new general purpose quantum mechanical molecular model. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:3902–3909. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Islam NB, Whalen DL, Yagi H, Jerina DM. pH dependence of the mechanism of hydrolysis of benzo[a]pyrene-cis-7,8-diol 9,10-epoxide catalyzed by DNA, poly(G), and poly(A) J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2108–2111. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta SC, Islam NB, Whalen DL, Yagi H, Jerina DM. Bifunctional catalysis in the nucleotide-catalyzed hydrolysis of (±)-7β,8α-dihydroxy-9α,10α-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene. J Org Chem. 1987;52:3812–3815. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nashed NT, Bax A, Loncharich RJ, Sayer JM, Jerina DM. Methanolysis of K-region arene oxides: comparison between acid-catalyzed and methoxide ion addition reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1711–1722. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nashed NT, Balani SK, Loncharich RJ, Sayer JM, Shipley DY, Mohan RS, Whalen DL, Jerina DM. Solvolysis of K-region arene oxides: substituent effects on reactions of benz[a]anthracene 5,6-oxide. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:3910. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nashed NT, Rao TVS, Jerina DM. Sterically induced methoxyl migration on acid-catalyzed dehydration of K-region trans-dihydrodiol monomethyl ethers. J Org Chem. 1993;58:6344–6348. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Utesch D, Glatt H, Oesch F. Rat hepatocyte-mediated bacterial mutagenicity in relation to the carcinogenic potency of benz[a]anthracene, benzo[a]pyrene, and twenty-five methylated derivatives. Cancer Res. 1987;47:1509–1515. and references therein. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Afshar CE, Katz AK, Carrell HL, Amin S, Desai D, Glusker JP. Three-dimensional structure of anti-5,6-dimethylchrysene-1,2-dihydrodiol-3,4-epoxide: a diol epoxide with a bay region methyl group. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1549–1553. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.8.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG. The approach to understanding aromatic hydrocarbon carcinogenesis. The central role of radical cations in metabolic activation. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;55:183–194. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90015-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG. Central role of radical cations in metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Xenobiotica. 1995;25:677–688. doi: 10.3109/00498259509061885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cavalieri EL, Roth R, Rogan EG. Metabolic activation of aromatic hydrocarbons by one-electron oxidation in relation to the mechanism of tumor initiation. In: Freudnthal RI, Jones PW, editors. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Chemistry, Metabolism, and Carcinogenesis. Vol. 1. Raven Press; New York: 1976. pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 60.RamaKrishna NVS, Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG, Dolnikowski G, Cerny RL, Gross ML, Jeong H, Jankowiak R, Small GJ. Synthesis and structure determination of the adducts of the potent carcinogen 7,12-dime thylbenz[a] anthracene and deoxyribonucleosides formed by electrochemical oxidation: models for metabolic activation by one-electron oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1863–1874. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flesher JW, Sydnor KL. Carcinogenicity of derivatives of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a] anthracene. Cancer Res. 1971;31:1951–1954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flesher JW, Sydnor KL. Possible role of 6-hydroxymethylbenzo[a]pyrene as a proximate carcinogen of benzo[a]pyrene and 6-methylbenzo[a]pyrene. Int J Cancer. 1973;11:433–437. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910110221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Surh YJ, Liem A, Miller EC, Miller JA. Metabolic activation of the carcinogen 6-hydroxymethylbenzo[a]pyrene: formation of an electrophilic sulfuric acid ester and benzylic DNA adducts in rat liver in vivo and in reaction in vitro. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10:1519–1528. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.8.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flesher JW, Horn J, Lehner AF. 7-Sulfooxy-methyl-12-methylbenz[a] anthracene is an exceptionally reactive electrophilic mutagen and ultimate carcinogen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;231:144–148. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flesher JW, Horn J, Lehner AF. 6-Sulfooxy-methylbenzo[a]pyrene is an ultimate electrophilic and carcinogenic form of the intermediary metabolite 6-hydroxymethylbenzo[a]pyrene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:554–558. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flesher JW, Horn J, Lehner AF. Formation of benzylic alcohols and meso-aldehydes by one electron oxidation of DMBA, a model for the first metabolic step in methylated carcinogenic hydrocarbon activation. Polycyclic Aromat Compd. 2004;24:501–511. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laali KK, Hansen PE. Generation and NMR studies of persistent fluoro(alkyl)pyrenium ions and their tetrahydro and hexahydro derivatives in superacid media. J Org Chem. 1993;58:4096–4104. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laali KK, Tanaka M, Hansen PE. First examples of fluorinated and chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) dications from benzo[a]pyrene, pyrene, and their alkyl-substituted derivatives. J Org Chem. 1998;63:8217–8223. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dipple A. Reactions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with DNA. In: Hemminki K, Dipple A, Shuker DEG, Kadlubar FF, Segerback D, Bartsch H, editors. DNA Adducts: Identification and Biological Significance. IARC Publications; Lyon: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG. Mechanism of tumor initiation by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mammals. In: Neilson AH, editor. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry: PAHs and Related Compounds. 3J. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 1998. pp. 81–117. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singletary KW, Parker HM, Milner JA. Identification and in vivo formation of 32P-postlabeled rat mammary DMBA-DNA adducts. Carcinogenesis. 1990;11:1959–1963. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.11.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Agarwal SK, Sayer JM, Yeh HJC, Pannell LK, Hilton BD, Pigott MA, Dipple A, Yagi H, Jerina DM. Chemical characterization of DNA adducts derived from the configurationally isomeric benzo[c]phenanthrene-3,4-diol 1,2-epoxides. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2497–2504. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cartesian coordinates of all optimized structures presented in this work. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.