Abstract

Anterior pituitary cells express γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-A receptor-channels, but their structure, distribution within the secretory cell types, and nature of action have not been clarified. Here we addressed these questions using cultured anterior pituitary cells from postpubertal female rats and immortalized αT3-1 and GH3 cells. Our results show that mRNAs for all GABAA receptor subunits are expressed in pituitary cells and that α1/β1 subunit proteins are present in all secretory cells. In voltage-clamped gramicidin-perforated cells, GABA induced dose-dependent increases in current amplitude that were inhibited by bicuculline and picrotoxin and facilitated by diazepam and zolpidem in a concentration-dependent manner. In intact cells, GABA and the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol caused a rapid and transient increase in intracellular calcium, whereas the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen was ineffective, suggesting that chloride-mediated depolarization activates voltage-gated calcium channels. Consistent with this finding, RT-PCR analysis indicated high expression of NKCC1, but not KCC2 cation/chloride transporter mRNAs in pituitary cells. Furthermore, the GABAA channel reversal potential for chloride ions was positive to the baseline membrane potential in most cells and the activation of ion channels by GABA resulted in depolarization of cells and modulation of spontaneous electrical activity. These results indicate that secretory pituitary cells express functional GABAA receptor-channels that are depolarizing.

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, and it acts through three structurally and pharmacologically distinct classes of receptors: GABAA and GABAC ligand-gated Cl− channels and G protein-coupled GABAB receptors (Owens & Kriegstein, 2002). To date, 16 different GABAA subunits (α1−6, β1−3, γ1−3, δ, ɛ, π and θ) have been cloned and sequenced from the mammalian nervous system. Functional receptors are heteromeric pentamers, the specific agonist for this receptor is muscimol, and the specific blocker is bicuculline (Sieghart & Sperk, 2002; Michels & Moss, 2007). The molecular components of GABAC receptors are ρ1−3 subunits, which form functional channels without assembling with GABAA-α and -β subunits. These receptors are specifically activated by (+)-cis-2-aminomethylcyclopropane carboxylic acid (Johnston, 2002). There are two GABAB subunits and functional receptors are probably heterodimers; the specific agonist for these receptors is baclofen (Bettler et al. 2004). GABAA/C channels are not always inhibitory. In immature neurons, intracellular Cl− concentration ([Cl−]i) is relatively high and GABA channels are depolarizing. During development, however, [Cl−]i progressively decreases through differential regulation of two electrically neutral cation/chloride transporters, termed NKCC1 and KCC2, and in most adult neurons GABA channels are hyperpolarizing (Payne et al. 2003; Fiumelli & Woodin, 2007). Furthermore, activated GABAB receptors always silence electrical activity and Ca2+ influx in target cells. This occurs through the Gi/oα-dependent inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and through the Gβγ-dependent inhibition of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and stimulation of inwardly rectifying K+ channels (Bettler et al. 2004).

Pituitary cells also express all three GABA receptor subtypes (Anderson & Mitchell, 1986a; Boue-Grabot et al. 2000; Nakayama et al. 2006), and very high radioactivity was detected in these cells 3–6 min after injection of [14C]GABA (Kuroda et al. 2000). Earlier studies suggested that GABA inhibits prolactin (PRL) release in vitro (Schally et al. 1977; Lamberts & Macleod, 1978; Enjalbert et al. 1979). In general, this action could be mediated by GABAB receptors, because these receptors inhibit basal adenylyl cyclase (Bettler et al. 2004), and both calcium and cAMP regulate exocytosis in secretory pituitary cells (Sikdar et al. 1990, 1998; Zorec et al. 1991; Sedej et al. 2005). However, the GABA-induced activation of a chloride current was shown in bovine lactotrophs (Inenaga & Mason, 1987) and a GABA-induced current with pharmacological properties of GABAA receptors was detected in neonatal rat pituitary cells (Zemkova et al. 1995). Specific [3H]muscimol binding sites were also identified in membranes from rat anterior pituitary cells (Anderson & Mitchell, 1986a; Berman et al. 1994). It has also been reported that muscimol inhibits PRL release in vitro and that bicuculline and picrotoxin block the action of GABA and muscimol (Grandison & Guidotti, 1979; Locatelli et al. 1979; Grossman et al. 1981), suggesting the presence of hyperpolarizing GABAA receptors in these cells and their potential inhibitory role in voltage-gated calcium influx and secretion. Contrary to these findings, GABA and muscimol were found to stimulate, rather than inhibit, secretion of GH, ACTH, TSH and LH in pituitary cells (Anderson & Mitchell, 1986b; Acs et al. 1987; Virmani et al. 1990). It has also been shown that GABA increases intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) in single identified rat lactotrophs; this effect is mimicked by muscimol and antagonized by picrotoxin (Lorsignol et al. 1994). Experiments with immortalized αT3-1 gonadotrophs also showed that GABA and muscimol increase [Ca2+]i (Williams et al. 2000). Augmentation of exocytosis and the depolarizing effect of GABA at high [Cl−]i has also been documented in melanotrophs from mouse pituitary tissue slices (Turner et al. 2005), and frogs (Desrues et al. 1995; Le Foll et al. 1998).

These observations raised questions about the endogenous [Cl−]i, the reversal potential for GABA-induced current, and the nature of GABA action (depolarizing versus hyperpolarizing) in secretory anterior pituitary cells. Furthermore, in these cells, the expression pattern of cation/chloride NKCC1 and KCC2 transporters has not been studied. An electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of GABAA receptor-channels in anterior pituitary cells from adult animals has not been examined in detail, and the complete set of GABAA receptor subunits expressed in pituitary cells has not been identified. To address these questions, here we made gramicidin-perforated patch-clamp recordings in cultured lactotrophs and gonadotrophs from adult female rats and immortalized αT3-1 and GH3 pituitary cells. Our results indicate that mRNA transcripts for all GABAA subunits are expressed in adult pituitary cells and that α1 and β1 subunit proteins are present in secretory anterior pituitary cells. We further show that lactotrophs, gonadotrophs and immortalized pituitary cells express functional channels that are depolarizing. The lower expression of KCC2 probably accounts for the lack of developmental shift of chloride homeostasis in the pituitary gland.

Methods

Chemicals

(−)-Bicuculline methochloride, muscimol, and zolpidem, were purchased from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). GABA, diazepam, gramicidin, picrotoxin, and all other chemicals were from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

Cell cultures

Experiments were performed on anterior pituitary cells from normal 8-week-old female Sprague–Dawley rats (Taconic Farm, Germantown, MD, USA). The rats were killed by exposure to CO2 gas in a rising concentration, followed by decapitation and removal of pituitary glands. Pituitary cells were dispersed and a two-stage Percoll discontinuous density gradient procedure was used to exclude blood and endothelial cells and obtain enriched lactotrophs and gonadotrophs as previously described (Koshimizu et al. 2000). Further identification in single cell studies was confirmed by the addition of dopamine and TRH (thyrotropin-releasing hormone) for lactotrophs and GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) for gonadotrophs (both from Peninsula Laboratories, Belmont, CA, USA). Mixed and purified pituitary cells were cultured in medium 199 containing Earle's salts, sodium bicarbonate, 10% heat-inactivated horse serum, penicillin (100 units ml−1) and streptomycin (100 μg ml−1) (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Immortalized GH3 cells were cultured in F12K medium containing 2.5% fetal bovine serum, 15% horse serum and 100 μg ml−1 gentamycin (Invitrogen). αT3-1 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 100 μg ml−1 gentamycin. Experiments were approved by the NICHD Animal Care and Use Committee.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). After DNase (Invitrogen) digestion, 3 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA with oligo-dT primers and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (RT; Invitrogen) according to the supplier's instructions. The first-strand cDNA products were used directly as templates for PCR amplification. PCR was performed with Platinum PCR Super Mix (Invitrogen). Amplification was initiated by a denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 36 (if not otherwise stated) cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 53°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 1 min. Amplification was terminated by final extension at 72°C for 7 min. GABAA receptor subunit sequences for sense and antisense primers are listed in Table 1 and were made by Gene Probe Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The same volumes of samples used for GABA subunit analyses were also subjected to a PCR reaction using β-actin-specific primers. The nested primers used for the PCR analyses of KCC2 and NKCC1 have been previously described (Yamada et al. 2004). Reactions without RT served as negative controls. The PCR products were analysed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide. Specificity of PCR products was confirmed by sequencing (Veritas, Rockville, MD, USA).

Table 1.

Sequences of GABAA receptor subunit primers used in RT-PCR analysis

| Subunits | Forward primers | Reverse primers | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | ACCGACTGTCAAGAATAGCC | TTGTCTGTCTCCTTCTGACG | 360 |

| α2 | CAATGCTTCTGACTCCGTTC | GGGCAGAGAACACAAACGC | 382 |

| α3 | TCCAGACCTACTTGCCATGT | CACTATGTTGAAGGTGGTGC | 358 |

| α4 | GTGAGATGATCTACACCTGG | TCCATGGCAGTCGCATAGG | 366 |

| α5 | CCTGCATCATGACAGTCATC | TGCTCTGATTGAGGCTGTAC | 427 |

| α6 | TTGCTCACAACATGACCACC | TGAAGTAGTTGACAGCTGCG | 608 |

| β1 | TGACCCTTGACAACAGGGTA | GTGATAGTCGTGGATATGCC | 386 |

| β2 | TGGAGATCGAAAGCTATGGC | TCGTTGTTGGCATTAGCAGC | 525 |

| β3 | GATAAAAGGCTCGCCTACTC | TGTGGCGAAGACAACATTCC | 401 |

| γ1 | AAATCTGATGCGCACTGGATA | ACCCAGGAAAGAACAACTGTT | 406 |

| γ2 | CCAATGGATGAACACTCCTG | GACGAAGAGATCCATTGCTG | 425 |

| γ3 | CAGAGGCTCACTGGATCAC | TAGTGTTTCTGAGGCCCATG | 272 |

| θ | ATTCCACTTCGAGCTCTCCT | CTCCTTGCTGGTAATTGTCC | 636 |

| π | CACTATATACCTCCGACAGC | GTGACCAGGGTGAAATACTG | 407 |

| ɛ | TCAGCCTAGTGGAAAGAAGC | CCAAGTGTTCTTCGCATCGA | 597 |

| δ | TGGACGAGCAGGAGTGCAT | CAGAGCCTTGATAGCAGAAG | 412 |

Immunocytochemistry

Dispersed anterior pituitary cells were plated on 25 mm glass coverslips coated with poly l-lysine, at a density of 500 000 cells per slide. Cells were first fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde pH 7.4 for 20 min and then thoroughly washed in PBS. Fixed cells were then treated with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min. Goat-anti-GABAA α1 and goat-anti-GABAA β1 primary antibodies, both obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), were applied overnight at 4°C (dilution 1: 50 in 1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate buffer). Specific blocking peptides for the primary antibodies were also obtained from Santa Cruz and applied according to the manufacturer's instructions. The secondary antibody, donkey-anti-goat Alexa fluor 488 (Invitrogen) was applied for 2 h at room temperature at a dilution of 1: 200. Control coverslips were stained without primary antibodies to test the non-specific labelling of the secondary antibody. Coverslips were mounted on the glass slides in Mowiol (Calbiochem), and cells were visualized under an inverted confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510, Jena, Germany). All images were taken using identical gain settings.

Patch-clamp recordings

GABA-induced currents and membrane potentials (Vm) were recorded from pituitary cells using the gramicidin-perforated patch-clamp technique, if not otherwise stated. Experiments with normal pituitary cells were done in 4–30 h and 7 days after dispersion, whereas recordings with immortalized cells were done 24–48 h after dispersion. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass tubes of 1.65 mm external diameter (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) on a horizontal Flaming Brown P-97 model puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA). The pipette was polished by heat to a tip resistance of 5–7 MΩ. Cells were investigated roughly 10 min after gigaohm seal formation when the seal resistance fell bellow 30 MΩ and was stable. The averaged cell membrane capacitance was 7.2 ± 0.23 pF (n = 31) for gonadotrophs, 7.1 ± 0.54 pF (n = 21) for lactotrophs, 10.8 ± 1.0 pF (n = 25) for αT3-1 cells, and 11.7 ± 1.4 pF (n = 10) for GH3 cells. Zero current Vm was measured in current-clamp mode. In voltage-clamp experiments, the Vm was held at −60 mV if not otherwise stated. Current-clamp and voltage-clamp recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). Results were collected and stored using the pCLAMP 10 software in conjunction with a Digidata 1322A A/D converter (Axon Instruments). Series resistance compensation of 50–80% was used and Vm was corrected for the Donnan and liquid junction potentials. Signals were filtered at 500 Hz and sampled at 1 kHz.

Solutions and drug application

During patch-clamp recording, cells were submerged and continuously perifused with an extracellular solution containing (in mm): 142 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose and 10 N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulphonic acid) (Hepes). The pH was adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH and the osmolarity was 290–300 mosmol l−1. The pipette solution contained (in mm): 70 potassium aspartate, 70 KCl, 3 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes; its pH was adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. Before measurement, gramicidin was added to the intracellular solution from a stock solution (10 mg ml−1 in DMSO) to obtain a final concentration of 50 μg ml−1. Stock solution of gramicidin was prepared on the day of the experiment, and the intracellular solution with gramicidin was prepared every 3 h. GABA and drug-containing solutions were delivered to the recording chamber by a gravity-driven microperfusion system containing eight glass tubes (each approximately 400 μm in diameter) with a common outlet (ALA Scientific Instruments, Westbury, NY, USA). Less than 200 ms was required for complete exchange of solutions around the recorded cells. The experiments were conducted at room temperature. The time between each GABA application was 60–120 s to permit recovery from receptor desensitization.

Single-cell calcium measurements

For [Ca2+]i measurements, freshly dispersed cells and cells cultured for 18–24 h or 5 days, were incubated in Hanks' M199 supplemented with 2 μm Fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) at 37°C for 60 min. Coverslips with cells were then washed and mounted on the stage of an Axiovert 135 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) attached to the Attofluor Digital Fluorescence Microscopy System (Atto Instruments, Rockville, MD, USA). Cells were examined under a ×40 oil immersion objective during exposure to alternating 340 and 380 nm light beams, and the intensity of light emission at 520 nm was measured. The ratio of light intensities F340/F380, which reflects changes in [Ca2+]i, was followed in several single cells simultaneously at a rate of one point per second.

Data analysis

The Sigma Plot 6.1 software was used for statistical analysis and curve fitting. Concentration–response data were fitted by a sigmoid function I/Imax = 1/(1 + (EC50/C)n), where I is the peak current evoked by GABA concentration C, Imax is the peak current induced by 100 μm GABA, n = 1.9 is the apparent Hill coefficient and the adjustable parameter EC50 is the concentration of GABA that produces a half-maximal response. All numerical values in the text are reported as mean ± s.e.m. and significant differences among means were determined by one-way ANOVA using SigmaStat 2000 v9.01 and Tukey's post hoc test, with P < 0.01.

Results

Detection of mRNA transcripts for GABAA receptor subunits

Total RNA was isolated from a mixed population of anterior pituitary cells 24 h after dispersion and PCR was conducted using first-strand cDNA samples with (+) and without (−) RT (Figs 1–3). Cortex was used as a control tissue for the expression of α1−α5, β1−β3, γ1−γ3 and θ, π and δ mRNAs, whereas the cerebellum was used for α6 and hypothalamus for ɛ subunit mRNAs (Sieghart & Sperk, 2002). The sequences of forward and reverse primers used in the PCR reaction are shown in Table 1. The mRNA transcripts for all α subunits were identified in mixed anterior pituitary cells (Fig. 1). However, the number of PCR cycles had to be increased to visualize the presence of α3, α5 and α6 mRNAs. Furthermore, anterior pituitary cells expressed mRNA transcripts for β1−β3 and γ1−γ3 subunits (Fig. 2) as well as transcripts for θ, π, δ and ɛ subunits (Fig. 3A). The size of the PCR products from both pituitary and brain tissues was appropriate. The specificity of primers was further confirmed by the sequence analysis of the PCR products. At the transcriptional level therefore anterior pituitary cells express most if not all of the components of GABAA receptors.

Figure 1. Detection of mRNA transcripts for GABAA receptor α subunits in anterior pituitary cells.

PCR was conducted using first-strand cDNA samples with (+) and without (−) RT. DNA markers are shown on both the left- and right-hand sides, and the size of markers is indicated on the left side. The arrows on the right indicate the expected sizes of the PCR products. Asterisks indicate subunits for which 40 instead of 36 detection cycles were used. As control tissues, cortex and cerebellum were used for the expression of α1−α5 and α6 mRNAs, respectively. β-Actin primers were used as an internal control to monitor the quality of RNA preparation (data not shown). The specificity of PCR products was confirmed by sequencing. Primer sequences are described in Table 1.

Figure 3. Detection of mRNA transcripts for other GABAA receptor subunits and NKCC1 and KKCC2 transporters in anterior pituitary cells.

A, cortex was used as a control tissue for θ, π and δ GABAA subunits and hypothalamus for ɛ subunits. B, detection of mRNA transcripts for cation/chloride KCC2 and NKCC1 transporters using nested primers. The outer and inner pairs of primers were previously described (Yamada et al. 2004). Cortex was used as a control tissue. The expected size for long and short KCC2 products are 522 and 237 base pairs, respectively; the comparable expected products for NKCC1 are 719 and 402 base pairs. Note the low expression of KCC2 in pituitary cells detected by both primers. The specificity of PCR products was confirmed by sequencing. For other details see Fig. 1 legend.

Figure 2. Detection of mRNA transcripts for GABAA receptor β and γ subunits in anterior pituitary cells.

Cortex was used as a control tissue. The specificity of PCR products was confirmed by sequencing. For other details see Fig. 1 legend.

Expression of NKCC1 and KCC2 mRNAs

We also examined the status of mRNA expression for NKCC1 and KCC2 chloride transporters in pituitary cells from adult animals. For this purpose, nested primers were used as previously described (Yamada et al. 2004). PCR analysis done using the outer and inner pairs of primers revealed the presence of NKCC1 products of the expected sizes in pituitary and brain tissues, and the specificity of products was further confirmed by sequence analysis (Fig. 3B). Similarly, PCR and sequence analyses revealed the presence of specific mRNA transcripts for KCC2 in the cortex tissue. There were also low detectable PCR products for KCC2 in RNA pools from pituitary derived by both primers, but we were unable to accumulate enough material for the sequence analysis. Because the low expression of KCC2 in embryonic neurons accounts for both elevated [Cl−]i and the depolarizing nature of GABAA receptor-channels (Fiumelli & Woodin, 2007), these results may suggest that [Cl−]i is also elevated in pituitary cells.

Immunocytochemical localization of GABAA receptor α1 and β1 subunits

Using specific antibodies for α1 and β1 GABAA receptor subunits, immunocytochemistry was performed in mixed anterior pituitary cells, from which endothelial and blood cells, but not folliculostellate cells, had been eliminated. Experiments completed 24 h after dispersion revealed the expression of both receptor subunit proteins in pituitary cells (Figs 4 and 5). GABAA-α1 immunoreactivity was present in virtually every cell, as documented by comparison of images obtained by transmitted light microscopy and laser-scanning confocal fluorescence (data not shown). This finding suggests that the expression of the GABAA-α1 receptor is common in anterior pituitary cells. The immunoreactivity was predominantly localized to the plasma membrane region, although cytoplasmic staining was considerable (Fig. 4A). Distribution was apparently polarized in most of the cells examined (Fig. 4B and C), although some cells showed pronounced immunoreactivity throughout the cell body excluding the nucleus (Fig. 4D). GABAA-β1 immunoreactivity was also observed in plasma membrane regions of all anterior pituitary cells (Fig. 5A). The distribution of the β1 subunit was somewhat less polarized, although this was clearly visible in some cells (Fig. 5B). Pronounced immunoreactivity could also be observed in many cell processes (Fig. 5B and C). Preincubation with the corresponding blocking peptide did not result in visible staining, indicating that the primary antibodies are specific (data not shown). When the primary antibody was omitted from the staining protocol, immunoreactivity was not detectable (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that GABAA receptor subunits are also expressed at the protein level in secretory pituitary cells.

Figure 4. Immunocytochemical localization of GABAA receptor α1 subunit in dispersed anterior pituitary cells.

A, the majority of anterior pituitary cells showed pronounced labelling. B, the staining was located at the plasma membrane (arrow), but was also prominent in the cytoplasm. C and D, most of the cells showed polarized distribution of the GABAA-α1 subunit (arrows), although some cells displayed uniformly stained cell membranes (D). Scale bars: 20 μm in A, 10 μm in B–D.

Figure 5. Immunocytochemical localization of the GABAA receptor β1 subunit in dispersed anterior pituitary cells.

A, low-level expression of this subunit could be observed close to the plasma membrane of most pituitary cells. B and C, two adjacent cells showing clear polarization in GABAA-β1 expression (B), a cell showing pronounced staining on the entire surface of the cell membrane (C), and cell processes were also marked (B and C). D, when the primary antibody was omitted, staining was not detectable. Scale bars: 20 μm in A and D, 10 μm in B and C.

GABA-induced increase in [Ca2+]i in pituitary cells

In normal pituitary cells, the effects of GABA and its agonists on [Ca2+]i in single cells was measured in freshly dispersed cells, 18–24 h after dispersion, and 5 days after dispersion. No changes in basal [Ca2+]i were observed in cells cultured for variable times and the GABA-induced rise in [Ca2+]i was observed in lactotrophs, gonadotrophs and unidentified cells in all three preparations. Figure 6A shows typical traces of GABA-induced rise in [Ca2+]i in a freshly dispersed gonadotroph (left), lactotroph (centre) and an unidentified cell (right). Identical results were obtained in 5 day-cultured cells (data not shown), further indicating that the depolarizing nature of GABA action does not reflect the cell damage-induced shift in [Cl−]i. In cells cultured overnight, GABA induced a rise in [Ca2+]i in 66 out of 85 of identified lactotrophs, 29 out of 31 identified gonadotrophs, and 66 out of 91 other unidentified pituitary cell types. Figure 6B shows representative traces of the 100 μm GABA-induced rise in [Ca2+]i in three identified lactotrophs (left) and gonadotrophs (right) cultured overnight. The averaged relative peak amplitude of calcium responses, expressed as ΔF340/F380, were comparable: 0.98 ± 0.9, 0.82 ± 21 and 1.02 ± 0.11 for lactotrophs, gonadotrophs and unidentified cells, respectively. The stimulatory action of GABA was mimicked by the GABAA/C receptor agonist muscimol but not by the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen in lactotrophs (Fig. 6C), gonadotrophs, and other cell types (data not shown). We also observed the rise in [Ca2+]i in GABA-stimulated αT3-1 immortalized gonadotrophs (Fig. 6D, left), and the rise was abolished when cells were bathed in calcium-deficient medium (Fig. 6D, right). These results suggest that functional GABAA receptors are expressed in the majority of anterior pituitary cells and that their activation leads to the depolarization of cells and activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ influx.

Figure 6. Depolarizing nature of GABA action in single identified pituitary cells.

A–C, GABA-induced rise in [Ca2+]i in normal pituitary cells. A, representative traces of GABA-induced responses in a freshly dispersed gonadotroph (left), lactotroph (centre), and an unidentified cell (right). B, GABA-induced rise in [Ca2+]i in three lactotrophs (left) and three gonadotrophs (right), 18–24 h after dispersion. C, the stimulatory action of GABA on lactotrophs cultured for 18–24 h was mimicked by the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol (right) but not by the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen (left). Traces shown are from 6 different cells. D, in αT3-1 cells, GABA-induced rise in [Ca2+]i when cells were bathed in Ca2+-containing (left), but not Ca2+-deficient, medium (right). Traces shown are from 6 different cells. In all panels, arrows indicate the moment of GABA, TRH, GnRH and drug application.

Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of GABA-induced currents

Electrophysiological recording from identified pituitary lactotrophs and gonadotrophs was performed using the gramicidin-perforated patch-clamp technique in cells cultured for 4–30 h. The top left panel of Fig. 7 shows a lactotroph that responded to TRH with a typical transient hyperpolarization (due to the activation of Ca2+-regulated SK potassium channels) followed by a sustained depolarization and increase in firing frequency (Ashworth & Hinkle, 1996). A similar effect of TRH was also observed in GH3 cells. Gonadotrophs from primary cultures responded to GnRH application with oscillatory hyperpolarizing changes in Vm driven by SK channels, which interrupted electrical activity as previously described (Kukuljan et al. 1992; Tse & Hille, 1992). In contrast, αT3-1 gonadotrophs responded to GnRH application in a manner comparable to that observed in TRH-stimulated cells (Fig. 7, left panels).

Figure 7. Concentration-dependent effects of GABA on chloride current in pituitary cells.

Left panels, effects of calcium-mobilizing TRH and GnRH agonists on electrical activity in normal (top two panels) and immortalized (bottom two panels) pituitary cells. Note the different patterns of GnRH-induced electrical activity in normal and immortalized αT3-1 gonadotrophs. Central panels, representative traces of inward currents induced by increasing GABA concentrations in cells voltage clamped to −60 mV. Right panels, GABA dose–response curves, with the estimated EC50 values derived from mean ± s.e.m. values from 3–10 cells. The amplitude of the GABA-induced current in GH3 cells was too low to generate reliable averaged data. Arrows indicate the moments of TRH (100 nm) and GnRH (1 nm, gonadotrophs and 100 nm, αT3-1 cells) application, and horizontal bars indicate the duration of GABA treatments.

After washout of GnRH/TRH, the GABA-induced current was recorded in cells voltage-clamped at −60 mV. Representative traces for four cell types are shown in the central panels of Fig. 7. In all cell types, GABA induced dose-dependent increases in current amplitude when recording was done in the same cell. There were significant differences in the mean amplitude values for maximum currents (response to 100 μm GABA) among cell types: lactotrophs, 461 ± 91 pA; gonadotrophs, 228 ± 65 pA; αT3-1, 495 ± 130 pA; GH3, 30 ± 10 pA (N = 6–10; P < 0.01). Dose–response analysis revealed that the sensitivity of GABAA receptors for agonist was higher in αT3-1 cells than in lactotrophs and gonadotrophs in primary culture (Fig. 7, right panels), suggesting the possibility that pentameric structures could differ in these cells. The amplitude of the GABA-induced current in GH3 cells was too low to generate reliable averaged data for construction of the dose–response curve. In the absence of gramicidin in the pipette, the maximum whole-cell current response to 100 μm GABA ranged from 50 pA to 2 nA in individual cells. Assuming that single-channel conductance is about 20 pS, the estimated number of GABAA channels per cell varied between 40 and 1600; this range is comparable to that observed in neurons from suprachiasmatic nuclei (Kretschmannova et al. 2003).

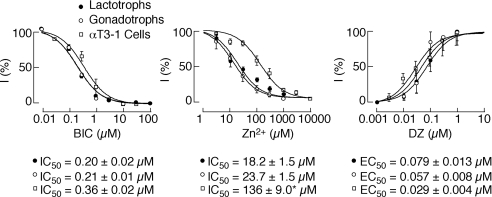

Pharmacological characterization of the GABA-induced current was performed in lactotrophs, gonadotrophs and αT3-1 cells using the whole-cell recording technique (Figs 8 and 9). In the absence of gramicidin, the cell type could be identified within the first 5 min of recording before washout of the cell interior. The GABA-induced current was completely inhibited by bicuculline in these cells (Fig. 8A, top panels), confirming the predominance of agonist action through GABAA receptor-channels. The current was also inhibited by picrotoxin (Fig. 8A, middle panels and Fig. 9). In lactotrophs and gonadotrophs, but not in αT3-1 cells, the current was also moderately inhibited by zinc (Fig. 8A, bottom panels and Fig. 9), suggesting that a fraction of GABAA receptor-channels in individual gonadotrophs and lactotrophs may lack the γ subunit (Draguhn et al. 1990; Smart & Constanti, 1990). On the other hand, the current was potentiated by diazepam (Fig. 8B, top panels) and zolpidem (Fig. 8B, bottom panels); the latter effect suggests the contribution of the α1 subunit in the functional channels.

Figure 8. Pharmacological characterization of GABA-induced currents in pituitary cells.

A, example records of the inhibitory effect of bicuculline (BIC), picrotoxin (PICRO) and zinc tested in the same cell during repetitive exposure to 30 μm GABA. B, facilitation of GABA-induced current by diazepam (DZ) and zolpidem (ZOLP). A current induced by 10 μm GABA was potentiated maximally to 217% by diazepam and 257% by zolpidem.

Figure 9. Dose-dependent effects of bicuculline (BIC), zinc (Zn2+) and diazepam (DZ) on GABA-induced current in lactotrophs, gonadotrophs and αT3-1 cells.

The inhibitory effect is expressed as a percentage of the control current induced by 10 μm GABA. The data from individual cells were fitted using the following equation: I = a + Imax/(1 + (C/IC50)n), where I was the observed current inhibition, Imax the maximum inhibition, a = 100 − Imax, C the drug concentration, IC50 the effective concentration producing half-maximal inhibition and n the Hill coefficient. Inhibition by zinc was never complete (a = 5%). Facilitation of GABA-induced currents by diazepam is expressed as a percentage of the maximally potentiated current. The data from individual cells were fitted using the sigmoid function as described in ‘Data analysis’. Theoretical curves were drawn using the mean values of IC50 or EC50. Each point represents the mean ± s.e.m. value from 3–10 cells. *P < 0.01 between cells in primary culture and αT3-1 cells.

Reversal potential for the GABA-induced chloride current

The reversal potentials (Erev) for GABA-induced currents in lactotrophs and gonadotrophs were determined in gramicidin-perforated cells clamped at different holding potentials. Figure 10A illustrates typical traces of GABA-induced currents in lactotrophs and gonadotrophs. Plotting the GABA-induced current as a function of Vm revealed an averaged Erev of −30 mV in lactotrophs with the calculated endogenous [Cl−]i of 45 mm. For gonadotrophs, the averaged Erev was −41 mV and the calculated [Cl−]i was 30 mm. The averaged baseline Vm was −52 mV in firing lactotrophs and −61 mV in gonadotrophs; these values were thus roughly 20 mV more negative than estimated Erev values in both cell types, indicating that GABA should be depolarizing in pituitary cells (Fig. 10B).

Figure 10. Reversal potentials for GABA-induced chloride currents in pituitary lactotrophs and gonadotrophs and their impact on spontaneous electrical activity.

A, typical gramicidin-perforated patch-clamp recording in lactotrophs and gonadotrophs held at different potentials. B, current–voltage relationship estimated from the peak current measurements in lactotrophs (left) and gonadotrophs (right). Data points are mean ± s.e.m. values and numbers in parentheses indicate number of cells. The Vm (baseline membrane potential in firing cells) and Erev (reversal potential for GABA-induced Cl− current) values are shown above plots. C, effects of GABA on electrical activity in lactotrophs (left) and gonadotrophs (right). Abolition of spontaneous firing of action potentials in lactotrophs (left) and a gonadotroph (right, bottom trace). Initiation of firing of action potentials in a quiescent gonadotroph (top right) and modulation of the firing frequency in a spontaneously firing gonadotroph (middle right). Note that a higher dose of GABA transiently facilitated the firing of action potentials followed by plateau fluctuations in a lactotroph and gonadotroph (middle panels). Horizontal dotted lines illustrate the baseline Vm. The measured Erev and values of GABA-induced inward current recorded at −65 mV (I) are shown below traces.

To test this hypothesis, in further experiments we analysed the effects of GABA on Vm oscillations in pituitary cells. The action of GABA on spontaneous electrical activity among pituitary lactotrophs and gonadotrophs varied, depending on the size of current, Erev, and Vm in a particular cell. The majority of lactotrophs fired action potentials spontaneously, and in 7 of 8 cells GABA induced a sustained depolarization. A similar effect of GABA treatment was also observed in 13 of 21 gonadotrophs. However, the level of depolarization varied among cells. The depolarizing effect of GABA was pronounced in a lactotroph in which the Erev was −18 mV (Fig. 10C, top left), in contrast to a lactotroph showing an Erev of −43 mV (Fig. 10C, bottom left) and a gonadotroph showing Erev of −37 mV (Fig. 10C, bottom right).

In the residual gonadotrophs and lactotrophs GABA treatment led to an increase in excitability. A small inward GABA current initiated the firing of action potentials in a quiescent gonadotroph (Fig. 10C, top right) and increased the firing frequency in a spontaneously firing cell (Fig. 10C, middle right). In both cell types, larger inward currents, usually triggered by higher GABA concentrations, induced a transient increase in the firing frequency followed by sustained depolarization, during which the Vm was clamped at Erev for GABA-induced current (Fig. 10C, middle panels). GABA was also depolarizing in 7 day-cultured cells (3 of 3 cells). These results indicate that the [Cl−]i in the majority of pituitary cells from adult animals is elevated, which makes GABAA channels in these cells depolarizing and leads to facilitation of steady or action-potential-driven voltage-gated Ca2+ influx.

Discussion

In search for a PRL inhibitory factor, Schally and coworkers isolated GABA from hypothalamus in 1977 (Schally et al. 1977). The subsequent studies showed that GABA is released from tuberoinfudibular and other hypothalamic regions, as well as from neurointermediate pituitary lobe axons (reviewed in Freeman et al. 2000). Concentrations of GABA in portal blood are higher than in peripheral blood, and electrical stimulation of median eminence induces an ∼8-fold increase in the rate of GABA release (Mitchell et al. 1983). In addition, GABA is synthesized and released in the pituitary (Duvilanski et al. 2000; Mayerhofer et al. 2001; Alvarez et al. 2005), and substance P modifies hypothalamic GABA release and anterior pituitary GABA concentration (Afione et al. 1990). Finally, injection of oestradiol leads to a 7-fold increase in anterior pituitary GABA concentration (Nicoletti et al. 1985).

Several lines of evidence shown previously and presented here support the conclusion that GABAA receptor-channels, which are responsible for most of the physiological actions of GABA in the brain (Sieghart & Sperk, 2002), are also expressed in secretory anterior pituitary cells. In agreement with earlier studies (Valerio et al. 1992; Berman et al. 1994; Boue-Grabot et al. 2000), our RT-PCR analysis indicated the presence of α1, α4, β1, β2, β3 and γ2 subunits in a mixed population of pituitary cells. Furthermore, we showed the presence of mRNA transcripts for α2, α3, α5, α6, γ1, γ3, θ, π, δ and ɛ subunits; the expression of α3, α5 and α6 mRNAs was somewhat lower. Thus, the whole repertoire of mRNAs for GABAA receptor subunits is present in anterior pituitary gland, providing the possibility for variable combinations of subunits into pentamers. Our immunocytochemical studies showed for the first time the expression of α1 and β1 subunit proteins in all secretory anterior pituitary cells and single-cell [Ca2+]i measurements revealed that functional channels are expressed in lactotrophs, gonadotrophs, and other unidentified cells.

We also confirmed earlier observations on lactotrophs (Lorsignol et al. 1994) that the stimulatory effect of GABA on [Ca2+]i was mimicked by muscimol, and we show the same effect in other pituitary cell subtypes from primary cultures and immortalized αT3-1 cells. The finding in the latter cells is in accordance with previously published data (Williams et al. 2000). The effect of GABA on [Ca2+]i was abolished by removal of extracellular calcium, suggesting that GABAA receptors in the majority of pituitary cells are depolarizing, leading to activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ influx. Stimulation of GABAC receptors in somatotrophs also increases [Ca2+]i (Gamel-Didelon et al. 2003), further supporting the depolarizing nature of GABA in pituitary cells from adults animals.

In further experiments, we performed electrophysiological measurements using gramicidin-perforated patch-clamp recordings to preserve [Cl−]i. In parallel to [Ca2+]i measurements, all anterior pituitary cells in primary culture held at −60 mV responded to GABA by generating inward currents in a dose-dependent manner. At this potential, GABA also induced high amplitude inward currents in all αT3-1 gonadotrophs; the EC50 value was lower than that observed in pituitary lactotrophs and gonadotrophs. These results suggest that expression and subunit composition of GABA receptors in primary cultures and immortalized cells might be different. The pharmacology of GABA-induced currents in pituitary cells was consistent with this view. The neuronal GABAA receptor and channel complex in vertebrates usually contains two α, two β and one γ or δ subunit and such pentamers are highly sensitive to the inhibitory effects of picrotoxin and bicuculline (Farrar et al. 1999). The availability of the α1 subunit is important for the development of zolpidem-sensitive GABAA receptors (Roberts & Kellogg, 2000), which we detected in all pituitary cell types. Zinc sensitivity is also subunit-dependent, and only receptors of embryonic neurons and recombinant GABAA receptors lacking γ subunits are strongly inhibited by zinc (Draguhn et al. 1990; Smart & Constanti, 1990). In this respect, a difference in the sensitivity of responses to zinc in cells from primary cultures and αT3-1 cells suggests that in lactotrophs and gonadotrophs some of the receptors may not express the γ subunit.

The most important conclusion from our electrophysiological investigations was that the baseline Vm for most cells was more negative by about 20 mV than the estimated Erev values for GABA-induced currents, indicating that [Cl−]i in the majority of pituitary cells from adult animals is elevated. In both electrophysiological measurements in gramicidin-perforated cells and calcium measurements in intact single normal and immortalized pituitary cells, we observed the depolarizing effects of GABA in freshly dissociated cells, as well as when cells were cultured for 1, 5 and 7 days. Thus, it is unlikely that dispersion of pituitary cells, culturing conditions, or injury-induced Cl− entry account for a shift from hyperpolarizing to depolarizing action of GABA as observed in neurons 24 h after trauma (van den Pol et al. 1996). GABA-induced depolarization of pituitary cells was associated with either an increase in the frequency of action potentials in spontaneously firing pituitary cells or a sustained depolarization.

Elevated [Cl−]i in pituitary cells is of physiological relevance not only for GABAA channels but also for other Cl−-conducting channels present in these cells (Sartor et al. 1990; Korn et al. 1991; Fahmi et al. 1995). In AtT20 cells, Ca2+-controlled chloride channels tend to maintain the Vm at a depolarized level (Korn et al. 1991). Elevated [Cl−]i in pituitary cells also provides a rationale for the interactions between Ca2+ and Cl− movements (Sartor et al. 1992). It has been also shown that PRL secretion is an osmotically driven process depending on [Cl−]i (Day & Hinkle, 1988). Additionally, granule fusion recorded by the patch-clamp technique is facilitated when the intrapipette chloride is elevated (Rupnik & Zorec, 1992; Turner et al. 2005).

The finding that GABAA channels are depolarizing in most pituitary cells also raised questions regarding the mechanism accounting for the high [Cl−]i. In general, Cl− homeostasis in most brain cells is controlled by NKCC1 and KCC2, two electrically neutral cation/chloride cotransporters. The ubiquitously expressed NKCC1 derives energy from the electrochemical gradient for Na+ to take up Cl−, whereas KCC2 uses the K+ gradient to facilitate Cl− extrusion (Fiumelli & Woodin, 2007). Thus, NKCC1 promotes intracellular accumulation of Cl− and KCC2 activity leads to reduction of [Cl−]i. In developing neurons with high [Cl−]i GABA is excitatory; in mature neurons with low [Cl−]i, however, GABA is inhibitory. The developmental switch from GABA excitation to inhibition is determined by down-regulation of NKCC1 and up-regulation of KCC2 transporters (Mercado et al. 2004). In the developing rat hippocampus, the up-regulation of KCC2 is completed by the end of the second postnatal week (Rivera et al. 1999).

Our experiments were conducted on anterior pituitary cells from 8-week-old rats. In contrast to the expression of NKCC1, mRNA expression for KCC2 (if present) was low in the anterior pituitary. Such a pattern of expression is consistent with the depolarizing action of GABA in most pituitary cells in primary culture, including gonadotrophs, as well as in the αT3-1 gonadotrophs derived from the fetal pituitary. In addition, some adult neurons, such as dopaminergic neurons in the striatum and a population of neurons in the nucleus reticularis thalami, do not express KCC2 (Gulacsi et al. 2003; Bartho et al. 2004). In accordance with our measurements of Erev from gramicidin-perforated patch-clamp recordings, imaging studies suggested high [Cl−]i in lactotrophs (Garcia et al. 1997). Chloride homeostasis is a more complex phenomenon, however, and may rely on the participation of other players like action potential-induced changes in Na+–K+-ATPase activity (Brumback & Staley, 2008). Thus, further investigations are required to clarify this issue in pituitary cells.

In summary, we analysed the expression of mRNAs for all GABAA subunits and NKCC1 and KCC2 transporters and performed a sequence analysis of all products. We also used immunocytochemistry to analyse the expression pattern of the GABAA-α1 and -β1 subunits among secretory pituitary cells. In addition, we measured the effects of GABA on [Ca2+]i in intact cells and GABA-induced currents in identified cells using gramicidin-perforated patch-clamp recordings. Our results indicate that mRNA transcripts for all GABAA subunits are expressed in pituitary cells and that α1 and β1 subunit proteins are expressed in all secretory anterior pituitary cells. We further showed that functional GABAA receptor-channels are present in gonadotrophs and lactotrophs from primary cultures as well as in immortalized lacto-somatotrophs and gonadotrophs. The lower expression of KCC2 in rat pituitary cells (as compared to rat brain) probably accounts for the depolarizing nature of GABAA channels in adult animals. It indicates that GABA has the ability to be a releasing factor in the pituitary but the physiological relevance of its excitatory effects are yet to be fully understood.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NICHD, NIH. The research fellowship of Dr Hana Zemkova was partly covered by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (305/07/0681). Confocal imaging was performed at the Microscopy and Imaging Core of NICHD with the assistance of Dr Vincent Schram. We are thankful to Dr Karla Kretschmannova for help with experiments.

References

- Acs Z, Szabo B, Kapocs G, Makara GB. γ-Aminobutyric acid stimulates pituitary growth hormone secretion in the neonatal rat. A superfusion study. Endocrinology. 1987;120:1790–1798. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-5-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afione S, Debeljuk L, Seilicovich A, Pisera D, Lasaga M, Diaz MC, Duvilanski B. Substance P affects the GABAergic system in the hypothalamo-pituitary axis. Peptides. 1990;11:1065–1068. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(90)90131-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez P, Cardinali D, Cano P, Rebollar P, Esquifino A. Prolactin daily rhythm in suckling male rabbits. J Circadian Rhythms. 2005;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Mitchell R. Distribution of GABA binding site subtypes in rat pituitary gland. Brain Res. 1986a;365:78–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Mitchell R. Effects of γ-aminobutyric acid receptor agonists on the secretion of growth hormone, luteinizing hormone, adrenocorticotrophic hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone from the rat pituitary gland in vitro. J Endocrinol. 1986b;108:1–8. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1080001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth R, Hinkle PM. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone-induced intracellular calcium responses in individual rat lactotrophs and thyrotrophs. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5205–5212. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartho P, Payne JA, Freund TF, Acsady L. Differential distribution of the KCl cotransporter KCC2 in thalamic relay and reticular nuclei. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:965–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JA, Roberts JL, Pritchett DB. Molecular and pharmacological characterization of GABAA receptors in the rat pituitary. J Neurochem. 1994;63:1948–1954. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63051948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettler B, Kaupmann K, Mosbacher J, Gassmann M. Molecular structure and physiological functions of GABAB receptors. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:835–867. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boue-Grabot E, Taupignon A, Tramu G, Garret M. Molecular and electrophysiological evidence for a GABAC receptor in thyrotropin-secreting cells. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1627–1632. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.5.7476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumback AC, Staley KJ. Thermodynamic regulation of NKCC1-mediated Cl− cotransport underlies plasticity of GABAA signaling in neonatal neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1301–1312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3378-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RN, Hinkle PM. Osmotic regulation of prolactin secretion. Possible role of chloride. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15915–15921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrues L, Vaudry H, Lamacz M, Tonon MC. Mechanism of action of γ-aminobutyric acid on frog melanotrophs. J Mol Endocrinol. 1995;14:1–12. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0140001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draguhn A, Verdorn TA, Ewert M, Seeburg PH, Sakmann B. Functional and molecular distinction between recombinant rat GABAA receptor subtypes by Zn2+ Neuron. 1990;5:781–788. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90337-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvilanski BH, Perez R, Seilicovich A, Lasaga M, Diaz MC, Debeljuk L. Intracellular distribution of GABA in the rat anterior pituitary. An electron microscopic autoradiographic study. Tissue Cell. 2000;32:284–292. doi: 10.1054/tice.2000.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjalbert A, Ruberg M, Arancibia S, Fiore L, Priam M, Kordon C. Independent inhibition of prolactin secretion by dopamine and γ-aminobutyric acid in vitro. Endocrinology. 1979;105:823–826. doi: 10.1210/endo-105-3-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmi M, Garcia L, Taupignon A, Dufy B, Sartor P. Recording of a large-conductance chloride channel in normal rat lactotrophs. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1995;269:E969–E976. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.269.5.E969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar SJ, Whiting PJ, Bonnert TP, McKernan RM. Stoichiometry of a ligand-gated ion channel determined by fluorescence energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10100–10104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiumelli H, Woodin MA. Role of activity-dependent regulation of neuronal chloride homeostasis in development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1523–1631. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamel-Didelon K, Kunz L, Fohr KJ, Gratzl M, Mayerhofer A. Molecular and physiological evidence for functional γ-aminobutyric acid GABAC receptors in growth hormone-secreting cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20192–20195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia L, Fahmi M, Prevarskaya N, Dufy B, Sartor P. Modulation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ conductance by changing Cl− concentration in rat lactotrophs. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1997;272:C1178–C1185. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.4.C1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandison L, Guidotti A. γ-Aminobutyric acid receptor function in rat anterior pituitary: evidence for control of prolactin release. Endocrinology. 1979;105:754–759. doi: 10.1210/endo-105-3-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A, Delitala G, Yeo T, Besser GM. GABA and muscimol inhibit the release of prolactin from dispersed rat anterior pituitary cells. Neuroendocrinology. 1981;32:145–149. doi: 10.1159/000123147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulacsi A, Lee CR, Sik A, Viitanen T, Kaila K, Tepper JM, Freund TF. Cell type-specific differences in chloride-regulatory mechanisms and GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in rat substantia nigra. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8237–8246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-23-08237.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inenaga K, Mason WT. γ-Aminobutyric acid modulates chloride channel activity in cultured primary bovine lactotrophs. Neuroscience. 1987;23:649–660. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston GA. Medicinal chemistry and molecular pharmacology of GABAC receptors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:903–913. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn SJ, Bolden A, Horn R. Control of action potentials and Ca2+ influx by the Ca2+-dependent chloride current in mouse pituitary cells. J Physiol. 1991;439:423–437. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshimizu TA, Tomic M, Wong AO, Zivadinovic D, Stojilkovic SS. Characterization of purinergic receptors and receptor-channels expressed in anterior pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4091–4099. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmannova K, Svobodova I, Zemkova H. Day-night variations in zinc sensitivity of GABAA receptor-channels in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;120:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukuljan M, Stojilkovic SS, Rojas E, Catt KJ. Apamin-sensitive potassium channels mediate agonist-induced oscillations of membrane potential in pituitary gonadotrophs. FEBS Lett. 1992;301:19–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80201-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda E, Watanabe M, Tamayama T, Shimada M. Autoradiographic distribution of radioactivity from 14C-GABA in the mouse. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;48:116–126. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000115)48:2<116::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberts SW, Macleod RM. Studies on the mechanism of the GABA-mediated inhibition of prolactin secretion. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1978;158:10–13. doi: 10.3181/00379727-158-40128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll F, Castel H, Soriani O, Vaudry H, Cazin L. Gramicidin-perforated patch revealed depolarizing effect of GABA in cultured frog melanotrophs. J Physiol. 1998;507:55–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.055bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli V, Cocchi D, Frigerio C, Betti R, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Racagni G, Muller EE. Dual γ-aminobutyric acid control of prolactin secretion in the rat. Endocrinology. 1979;105:778–785. doi: 10.1210/endo-105-3-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorsignol A, Taupignon A, Dufy B. Short applications of γ-aminobutyric acid increase intracellular calcium concentrations in single identified rat lactotrophs. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60:389–399. doi: 10.1159/000126773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerhofer A, Hohne-Zell B, Gamel-Didelon K, Jung H, Redecker P, Grube D, Urbanski HF, Gasnier B, Fritschy JM, Gratzl M. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA): a para- and/or autocrine hormone in the pituitary. FASEB J. 2001;15:1089–1091. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0546fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado A, Mount DB, Gamba G. Electroneutral cation-chloride cotransporters in the central nervous system. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:17–25. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000010432.44566.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels G, Moss SJ. GABAA receptors: properties and trafficking. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42:3–14. doi: 10.1080/10409230601146219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R, Grieve G, Dow R, Fink G. Endogenous GABA receptor ligands in hypophysial portal blood. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;37:169–176. doi: 10.1159/000123539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama Y, Hattori N, Otani H, Inagaki C. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA)-C receptor stimulation increases prolactin (PRL) secretion in cultured rat anterior pituitary cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:1705–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti F, Grandison L, Meek JL. Effects of repeated administration of estradiol benzoate on tubero-infundibular GABAergic activity in male rats. J Neurochem. 1985;44:1217–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb08746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, Kriegstein AR. Is there more to GABA than synaptic inhibition? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:715–727. doi: 10.1038/nrn919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JA, Rivera C, Voipio J, Kaila K. Cation-chloride co-transporters in neuronal communication, development and trauma. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C, Voipio J, Payne JA, Ruusuvuori E, Lahtinen H, Lamsa K, Pirvola U, Saarma M, Kaila K. The K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature. 1999;397:251–255. doi: 10.1038/16697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AA, Kellogg CK. Synchronous postnatal increase in a1 and g2L GABAA receptor mRNAs and high affinity zolpidem binding across three regions of rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;119:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupnik M, Zorec R. Cytosolic chloride ions stimulate Ca2+-induced exocytosis in melanotrophs. FEBS Lett. 1992;303:221–223. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80524-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor P, Dufy-Barbe L, Corcuff JB, Taupignon A, Dufy B. Electrophysiological response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone of rat lactotrophs in primary culture. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1990;258:E311–E319. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.2.E311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor P, Dufy-Barbe L, Vacher P, Dufy B. Calcium-activated chloride conductance of lactotrophs: comparison of activation in normal and tumoral cells during thyrotropin-releasing-hormone stimulation. J Membr Biol. 1992;126:39–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00233459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schally AV, Redding TW, Arimura A, Dupont A, Linthicum GL. Isolation of γ-amino butyric acid from pig hypothalami and demonstration of its prolactin release-inhibiting (PIF) activity in vivo and in vitro. Endocrinology. 1977;100:681–691. doi: 10.1210/endo-100-3-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedej S, Rose T, Rupnik M. cAMP increases Ca2+-dependent exocytosis through both PKA and Epac2 in mouse melanotrophs from pituitary tissue slices. J Physiol. 2005;567:799–813. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W, Sperk G. Subunit composition, distribution and function of GABAA receptor subtypes. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:795–816. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikdar SK, Kreft M, Zorec R. Modulation of the unitary exocytic event amplitude by cAMP in rat melanotrophs. J Physiol. 1998;511:851–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.851bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikdar SK, Zorec R, Mason WT. cAMP directly facilitates Ca-induced exocytosis in bovine lactotrophs. FEBS Lett. 1990;273:150–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81072-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart TG, Constanti A. Differential effect of zinc on the vertebrate GABAA-receptor complex. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;99:643–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse A, Hille B. GnRH-induced Ca2+ oscillations and rhythmic hyperpolarizations of pituitary gonadotropes. Science. 1992;255:462–464. doi: 10.1126/science.1734523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JE, Sedej S, Rupnik M. Cytosolic Cl− ions in the regulation of secretory and endocytotic activity in melanotrophs from mouse pituitary tissue slices. J Physiol. 2005;566:443–453. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerio A, Tinti C, Spano P, Memorandum M. Rat pituitary cells selectively express mRNA encoding the short isoform of the g2 GABAA receptor subunit. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;13:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90054-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN, Obrietan K, Chen G. Excitatory actions of GABA after neuronal trauma. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4283–4292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04283.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virmani MA, Stojilkovic SS, Catt KJ. Stimulation of luteinizing hormone release by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonists: mediation by GABAA-type receptors and activation of chloride and voltage-sensitive calcium channels. Endocrinology. 1990;126:2499–2505. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-5-2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Bence M, Everest H, Forrest-Owen W, Lightman SL, McArdle CA. GABAA receptor mediated elevation of Ca2+ and modulation of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone action in aT3-1 gonadotropes. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:159–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada J, Okabe A, Toyoda H, Kilb W, Luhmann HJ, Fukuda A. Cl− uptake promoting depolarizing GABA actions in immature rat neocortical neurones is mediated by NKCC1. J Physiol. 2004;557:829–841. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemkova H, Vanecek J, Krusek J. Electrophysiological characterization of GABAA receptors in anterior pituitary cells of newborn rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;62:123–129. doi: 10.1159/000126996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorec R, Sikdar SK, Mason WT. Increased cytosolic calcium stimulates exocytosis in bovine lactotrophs. Direct evidence from changes in membrane capacitance. J Gen Physiol. 1991;97:473–497. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]