Abstract

The present work investigates the effect of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) on native TRPC6 channel activity in freshly dispersed rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes using patch clamp recording and co-immunoprecipitation methods. Inclusion of 100 μm diC8-PIP2 in the patch pipette and bathing solutions, respectively, inhibited angiotensin II (Ang II)-evoked whole-cell cation currents and TRPC6 channel activity by over 90%. In inside-out patches diC8-PIP2 also inhibited TRPC6 activity induced by the diacylglycerol analogue 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG) with an IC50 of 7.6 μm. Anti-PIP2 antibodies potentiated Ang II- and OAG-evoked TRPC6 activity by about 2-fold. Depleters of tissue PIP2 wortmannin and LY294002 stimulated TRPC6 activity, as did the polycation PIP2 scavenger poly-l-lysine. Wortmannin reduced Ang II-evoked TRPC6 activity by over 75% but increased OAG-induced TRPC6 activity by over 50-fold. Co-immunoprecipitation studies demonstrated association between PIP2 and TRPC6 proteins in tissue lysates. Pre-treatment with Ang II, OAG and wortmannin reduced TRPC6 association with PIP2. These results provide for the first time compelling evidence that constitutively produced PIP2 exerts a powerful inhibitory action on native TRPC6 channels.

Members of the canonical class of transient receptor potential (TRPC) non-selective Ca2+-permeable cation channels are present in many types of smooth muscle (see Large, 2002; Beech et al. 2004; Albert & Large, 2006; Albert et al. 2007). These channels have been implicated in many physiological responses in vascular tissue such as depolarization, contraction, gene expression, cell growth and proliferation. Classically TRPC channels are often described as receptor-operated (ROCs) or store-operated channels (SOCs) with ROCs being stimulated by G-protein-coupled receptors linked to phospholipase C (PLC) and SOCs stimulated by depletion of internal Ca2+ stores. However, little is known about the precise mechanisms by which TRPC-mediated ROCs and SOCs are gated.

In rabbit vascular myocytes there are several TRPC ROC isoforms where one product of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis (PIP2) by PLC, diacylglycerol (DAG), initiates channel opening by a protein kinase C (PKC)-independent mechanism. DAG stimulates TRPC6 activity in portal vein and mesenteric artery, TRPC3 in ear artery and TRPC3/TRPC7 in coronary artery myocytes in this manner although it is not known how DAG produces channel gating (Helliwell & Large, 1997; Inoue et al. 2001; Albert et al. 2005, 2006; Saleh et al. 2006; Peppiatt-Wildman et al. 2007). Moreover the other product of PIP2 hydrolysis, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), markedly potentiates TRPC6-like and TRPC3/TRPC7 channel opening in, respectively, portal vein and coronary artery myocytes (Albert & Large, 2003; Peppiatt-Wildman et al. 2007). In the present work we have investigated the role of PIP2 in regulating native TRPC6 activity since PIP2 is the precursor of both DAG and IP3 and has been shown to independently regulate the function of many ion channel proteins including members of the TRP superfamily (see Suh & Hille, 2005; Rohacs, 2007; Voets & Nilius, 2007). Recently it was demonstrated that PIP2 increased expressed TRPC3, -C6 and -C7 activity in HEK293 cells (Lemonnier et al. 2008) and it was suggested that phosphoinositides, including PIP2, mediate increases in TRPC6 activity due to disruption of calmodulin (CaM) binding to fusion proteins containing the C-termini of TRPC6 (Kwon et al. 2007). In contrast, PIP2 inhibited receptor-operated TRPC4α activity in HEK293 cells (Otsuguro et al. 2008). These results illustrate complex effects of PIP2 on expressed TRPC channels but to date there have been no studies on the effect of PIP2 on native TRPC channels. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the effect of PIP2 on TRPC6 channels in freshly dispersed rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes. These novel results show that PIP2 exerts a powerful inhibitory brake on agonist-evoked TRPC6 activity. Moreover, simultaneous depletion of PIP2 and production of DAG are necessary for optimal channel activation.

Methods

Cell isolation

New Zealand White rabbits (2–3 kg) were killed using i.v. sodium pentobarbitone (120 mg kg−1, in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986). 1st to 5th order mesenteric arteries were dissected free from fat and connective tissue and enzymatically digested into single myocytes using methods previously described (Saleh et al. 2006).

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell and single cation currents were recorded with an AXOpatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, USA) at room temperature (20–23°C) using whole-cell recording, cell-attached, inside-out and outside-out patch configurations and data acquisition and analysis protocols as previously described (Saleh et al. 2006). Briefly, single channel current amplitudes were calculated from idealized traces of at least 60 s in duration using the 50% threshold method with events lasting for less than 0.664 ms (2× rise time for a 1 kHz, −3 db, low-pass filter) being excluded from analysis. Figure preparation was carried out using MicroCal Origin software 6.0 (MicroCal Software Inc., MA, USA) where inward single channel currents are shown as downward deflections. Open probability (NPo) was calculated using the equation: NPo =  where n is the number of channels in the patch, On is the time spent at each open level and T is the total recording time.

where n is the number of channels in the patch, On is the time spent at each open level and T is the total recording time.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Dissected tissues were either flash frozen and stored at −80°C for subsequent use or immediately placed into 10 mg ml−1 RIPA lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) supplemented with protease inhibitors and then homogenized on ice by sonication for at least 3 h. The total cell lysate (TCL) was collected by centrifugation at 10 g for 10 min at 4°C and then protein content was quantified using the Bio-Rad protein dye reagent (Bradford method). TCL was pre-cleared using A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C using the appropriate antibody and A/G agarose bead conjugate. Alternatively, the immunoprecipitation protocol was carried out using the Upstate Catch and Release kit (Millipore), where spin columns were loaded with 500 μg of cell lysates, 4 μg of antibody and immunoprecipitated for 2 h at room temperature.

Protein samples were eluted with Laemmli sample buffer and incubated at 95°C for 2 min. One-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis was performed in 4–12% Bis–Tris gels in a Novex mini-gel system (Invitrogen) with 20 μg of total protein loaded in each lane. Separated proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes in a Biorad trans-blot SD semi-dry transfer cell or using the iBlot apparatus (Invitrogen). Blots were incubated for 1–4 h with 5% (weight/volume) non-fat milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) to block non-specific protein binding. Membranes were then incubated with appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C (where possible alternative antibodies raised against different epitopes were used for immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis). Following antibody removal blots were washed for 2 h with milk–PBST. Blots were subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Sigma) or sheep anti-goat (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) IgG secondary antibody diluted 1: 1000–1: 5000 in milk–PBST, washed 3 times in PBST, and treated with ECL chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce) for 1 min and exposed to photographic films. In loading control experiment anti-β-actin antibodies (mouse monoclonal, Sigma, UK) were also added to the immunoprecipitate and immunoblot procedures to show that expression levels of β-actin did not change during the experimental conditions. Moreover, immunoblot control data showed that anti-PIP2 and anti-TRPC6 antibodies did not recognize β-actin following immunoprecipitation with only anti-β-actin antibodies. Data shown represent n values of at least three separate experiments.

Anti-TRPC6 and anti-PIP2 antibodies

Polyclonal TRPC6 antibody generated in rabbits against an intracellular epitope was purchased from Alomone Laboratories (Jerusalem, Israel) and the selectivity and negligible cross-reactivity of this antibody for its target protein has been previously confirmed (Liu et al. 2005; Sours et al. 2006). An alternative polyclonal antibody for TRPC6 generated in goats against a different intracellular epitope was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and the specificity of this antibody has also been previously confirmed (Liu et al. 2005). Mouse monoclonal PIP2 antibody generated against liposomes of human origin constituted with the phospholipid was purchased from Assay Designs (USA). This anti-PIP2 antibody has previously been used in electrophysiological (Liou et al. 1999; Bian et al. 2001; Ma et al. 2002; Pian et al. 2006; Xie et al. 2008) and immunoprecipitation studies (Asteggiano et al. 2001; Beauge et al. 2002; Yue et al. 2002) to investigate the role of PIP2 in regulating ion channels and exchangers.

Solutions and drugs

The bathing solution used to measure whole-cell cation currents was K+ free and contained (mm): NaCl (126), CaCl2 (1.5), Hepes (10), glucose (11), DIDS (0.1), niflumic acid (0.1) and nicardipine (0.005), pH to 7.2 with NaOH. In cell-attached patch experiments the membrane potential was set to approximately 0 mV by perfusing cells in a KCl external solution containing (mm): KCl (126), CaCl2 (1.5), Hepes (10) and glucose (11), pH to 7.2 with 10 m KOH. Nicardipine (5 μm) was also included to prevent smooth muscle cell contraction by blocking Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels.

The patch pipette solution used to measure whole-cell cation currents (intracellular solution) was also K+ free and contained (mm): CsCl (18), caesium aspartate (108), MgCl2 (1.2), Hepes (10), glucose (11), BAPTA (10), CaCl2 (4.8, free internal Ca2+ concentration approximately 100 nm as calculated using EQCAL software), Na2ATP (1) and NaGTP (0.2), pH 7.2 with Tris. The patch pipette solution used for both cell-attached and inside-out patch recording (extracellular solution) was K+ free and contained (mmol l−1): NaCl (126), CaCl2 (1.5), Hepes (10), glucose (11), TEA (10), 4-AP (5), iberiotoxin (0.0002), DIDS (0.1), niflumic acid (0.1) and nicardipine (0.005), pH to 7.2 with NaOH. The composition of the bathing solution used in inside-out experiments (intracellular solution) was the same as the patch pipette solution used for whole-cell recording except that 1 mm BAPTA and 0.48 mm CaCl2 were included (free internal Ca2+ concentration approximately 100 nm). Under these conditions VDCCs, K+ currents, swell-activated Cl− currents and Ca2+-activated conductances are abolished and non-selective cation currents could be recorded in isolation.

DiC8-PIP2 was purchased from Cayman chemicals (UK). All other drugs were purchased from Calbiochem (UK), Sigma (UK) or Tocris (UK) and agents were dissolved in distilled H2O or DMSO (0.1%). DMSO alone had no effect on TRPC6 channel activity. The values are the mean of n cells ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was carried out using paired (comparing effects of agents on the same cell) or unpaired (comparing effects of agents between cells) Students' t test with the level of significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

DiC8-PIP2 inhibits native TRPC6 channel activity in rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes

In initial experiments we investigated the effect of including 100 μm diC8-PIP2, a water-soluble form of PIP2, in the patch pipette solution on angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced whole-cell cation currents in mesenteric artery myocytes. In these experiments we used 1 nm Ang II since previous work showed that 1 nm Ang II activated native TRPC6 channels (Saleh et al. 2006). Figure 1Aa and b shows that 100 μm diC8-PIP2 reduced the mean peak amplitude of whole-cell cation currents induced by 1 nm Ang II from −26 ± 8 pA (n = 7) to −2 ± 0.5 pA (n = 7, P < 0.01) at −50 mV. Figure 1Ac also shows that the Ang II-evoked mean current–voltage (I–V) relationship was inhibited by 100 μm diC8-PIP2 at all membrane potentials between −100 mV and +90 mV.

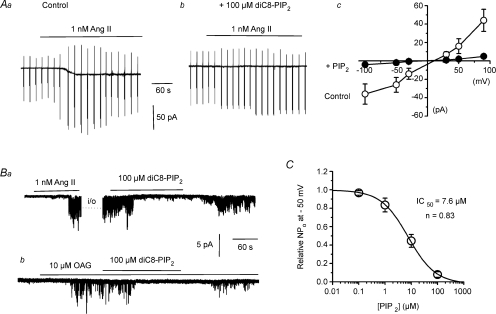

Figure 1. DiC8-PIP2 inhibits Ang II-evoked whole-cell cation currents and single TRPC6 channel activity in rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes.

Aa and b, inclusion of 100 μm diC8-PIP2 in the patch pipette solution inhibits whole-cell cation currents evoked by 1 nm Ang II. Ac, mean I–V relationship showing diC8-PIP2 inhibits Ang II-evoked cation currents at all potentials tested (n = at least 4 per point). Ba, 100 μm diC8-PIP2 inhibited TRPC activity in an inside-out patch which was initially activated by 1 nm Ang II in a cell-attached patch (i/o, inside-out patch). Bb, 100 μm diC8-PIP2 inhibited TRPC activity induced by 10 μm OAG in an inside-out patch. C, inhibitory action of diC8-PIP2 on OAG-evoked TRPC6 activity in inside-out patches had an IC50 value of 7.6 μm (n = at least 4 per point).

To obtain precise information on the effect of PIP2 on TRPC6 channel activity and to exclude the possibility of observing actions of PIP2 on multiple cation conductances we studied the effect of PIP2 on TRPC6 activity at the single channel level. Figure 1Ba shows that bath application of 1 nm Ang II evoked channel activity in a cell-attached patch, which had similar unitary properties to TRPC6 channels previously described (Saleh et al. 2006), and was maintained following excision of the patch into the inside-out configuration for up to 30 min. Figure 1Ba shows that bath application of 100 μm diC8-PIP2 to the cytosolic surface of the inside-out patch reversibly inhibited the mean open probability (NPo) of Ang II-evoked TRPC6 activity from 3.81 ± 0.84 to 0.43 ± 0.21 (n = 6, P < 0.05) at −50 mV. Previously it has been shown that DAG activates TRPC6 channels in mesenteric artery myocytes by a PKC-independent mechanism. Figure 1Bb shows that bath application of 10 μm 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG), a cell-permeable DAG analogue, to an inside-out patch also induced channel activity with TRPC6 properties (Saleh et al. 2006). Moreover, Fig. 1Bb shows that bath application of 100 μm diC8-PIP2 reversibly inhibited mean NPo of OAG-induced TRPC6 activity from 1.49 ± 0.03 to 0.09 ± 0.03 (n = 6, P < 0.01) at −50 mV diC8-PIP2 at 100 μm also inhibited OAG-evoked TRPC6 activity by 89 ± 5% (n = 3, data not shown) in the presence of the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine (3 μm) indicating that PIP2-mediated inhibition of TRPC6 did not involve PKC (see Saleh et al. 2006). Figure 1C shows a dose–response curve of diC8-PIP2 on TRPC6 activity induced by 10 μm OAG in inside-out patches at −50 mV with 50% inhibition (IC50) produced by 7.6 μm diC8-PIP2.

Endogenous PIP2 inhibits TRPC6 activity

The above data clearly demonstrate that diC8-PIP2 has a profound inhibitory action on TRPC6 activity in mesenteric artery myocytes. Therefore we investigated the role of endogenous PIP2 on TRPC6 activity by studying the effect of anti-PIP2 antibodies on TRPC6 activity induced by Ang II and OAG in inside-out patches.

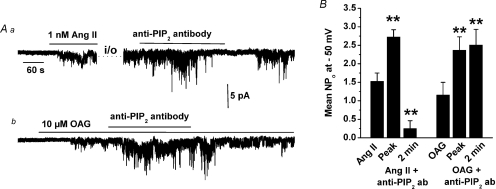

Figure 2Aa shows that bath application of anti-PIP2 antibodies at 1: 200 to an inside-out patch, in which TRPC6 channels were activated initially in the cell-attached mode by 1 nm Ang II (i.e. similar to Fig. 1B), increased TRPC6 activity (about 2-fold) but after 2 min there was a marked decrease in NPo (Fig. 2Aa and B). Figure 2Ab illustrates that bath application of anti-PIP2 antibodies at 1: 200 dilution also increased OAG-evoked TRPC6 activity in inside-out patches by approximately 2-fold but unlike Ang II there was no subsequent inhibition of channel activity in the continued presence of the antibody (Fig. 2Ab and B).

Figure 2. Anti-PIP2 antibody potentiates TRPC6 channel activity.

Aa, 1: 200 dilution of anti-PIP2 antibodies transiently increased TRPC6 activity in an inside-out patch which was induced by 1 nm Ang II in cell-attached mode. Subsequently the Ang II-evoked response was inhibited in the presence of the anti-PIP2 antibody. Ab, 1: 200 dilution of anti-PIP2 antibodies produced a sustained increase of OAG-evoked TRPC6 activity in an inside-out patch. B, mean data of effect of anti-PIP2 antibodies on Ang II- and OAG-induced TRPC6 activity (n = 6 for all conditions, **P < 0.01).

Agents that deplete PIP2 levels activate TRPC6 activity in un-stimulated mesenteric artery myocytes

These present results indicate that endogenous PIP2 exerts a powerful inhibitory action of TRPC6 channels. In addition, previous work using an inhibitor of DAG lipase showed that these channels are also activated by constitutive DAG production (Saleh et al. 2006). We therefore investigated the effect of wortmannin and LY294002 on cell-attached patches from unstimulated myocytes since at high concentrations these agents are known to inhibit phosphoinositol (PI)-4-kinases leading to a reduction in the generation of PIP2 and consequently a depletion of PIP2 levels (Suh & Hille, 2005).

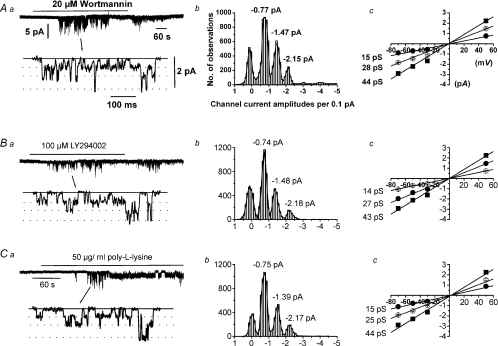

Figure 3Aa shows that bath application of 20 μm wortmannin evoked channel activity with a mean peak NPo value of 1.79 ± 0.42 (n = 14) at −50 mV. Amplitude histograms of wortmannin-induced channel currents could be fitted by the sum of three Gaussian curves with three sub-conductance states of 15 pS, 28 pS and 44 pS which all had a reversal potential (Er) of about 0 mV (Fig. 3Ab and c). These characteristics are identical to Ang II- and OAG-evoked TRPC6 channel currents (see Saleh et al. 2006). Figure 3Ba, b and c shows that bath application of 100 μm LY294002 evoked TRPC6 activity with a mean peak NPo value of 0.37 ± 0.01 (n = 60) at −50 mV. TRPC6 activity induced by wortmannin and LY294002 was transient with no activity detected after 5 min in the presence of these agents. At concentrations that do not inhibit PI-4 kinases, wortmannin (50 nm) and LY294002 (10 μm) had no effect on TRPC6 activity.

Figure 3. Agents that deplete PIP2 evoke TRPC6 channel activity.

A and B, respectively, 20 μm wortmannin and 100 μm LY294002 transiently activated channel activity in cell-attached patches (a) which had similar amplitude histograms (b) and unitary conductances and Er values (c). C, 50 μg ml−1 poly-l-lysine activated channel currents in an inside-out patch (a) which had a similar properties to those evoked by wortmannin and LY294002 (b and c).

Figure 3Ca shows that bath application of the polycation PIP2 scavenger poly-l-lysine (50 μg ml−1) to an inside-out patch activated channel activity with a mean peak NPo value of 1.52 ± 0.34 (n = 10) at −50 mV. These poly-l-lysine-evoked channel currents had similar conductances/Er values to those induced by wortmannin and LY294002 (Fig. 3Cb and c).

Depletion of PIP2 levels reduces Ang II- but increases OAG-evoked TRPC6 activity

These results show that endogenous and exogenous PIP2 inhibits Ang II- and OAG-evoked TRPC6 activity and that PIP2 also prevents channel opening induced by constitutive generation of DAG. However, stimulation of AT1 receptors by Ang II involves PLC-mediated PIP2 hydrolysis leading to DAG production and TRPC6 activity (Saleh et al. 2006) whereas OAG acts on TRPC6 downstream of PIP2 hydrolysis. Therefore we compared the effects of Ang II and OAG on TRPC6 activity in the presence of wortmannin in cell-attached patches.

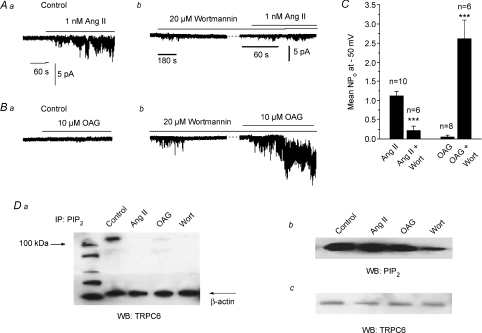

Figure 4Aa, b and C shows that 15 min preincubation with 20 μm wortmannin reduced Ang II-evoked TRPC6 activity by about 75%. In contrast, Fig. 4Ba, b and C shows that 10 μm OAG produced little stimulation of TRPC6 activity in control cell-attached patches. However, following pre-treatment with 20 μm wortmannin for 15 min OAG-evoked TRPC activity was markedly increased by over 50-fold (P < 0.001).

Figure 4. Wortmannin-induced depletion of PIP2 decreases Ang II-evoked and increases OAG-induced TRPC6 activity in cell-attached patches.

A shows that Ang II-evoked TRPC6 activity (a) is decreased after pre-treatment with wortmannin (b). B illustrates that OAG-induced TRPC6 activity (a) is markedly increased following pre-treatment with wortmannin (b). C, mean data showing effect of wortmannin on Ang II- and OAG-induced TRPC6 activity (***P < 0.001). Da shows a co-immunoprecitation experiment in which mesenteric artery tissue lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-PIP2 antibody and then Western blotted (WB) with an anti-TRPC6 antibody. In control conditions a band of ∼110 kDa was observed which was absent after pre-treatment of the tissue with 20 μm wortmannin, 1 nm Ang II and 10 μm OAG for 15 min. Note that similar results were obtained with both anti-TRPC6 antibodies (Alomone and Santa Cruz). Db, immunoblot with anti-PIP2 antibody showing reduction of total tissue PIP2 levels after incubation with 20 μm wortmannin for 15 min. Pre-treatment with 1 nm Ang II and 10 μm OAG for 15 min had little effect on total tissue PIP2 levels. Dc, immunoblot with anti-TRPC6 antibody showing pre-treatment of tissue with 20 μm wortmannin, 1 nm Ang II and 10 μm OAG and for 15 min had no effect on expression of TRPC6 protein. Note that all immunoprecipiation and immunoblot experiments were from at least n = 3.

Association of PIP2 with TRPC6 proteins is reduced by pre-treatment with wortmannin and OAG

These data suggest that PIP2 inhibits TRPC6 activity stimulated by Ang II and OAG but also that PIP2 acts as a precursor for endogenous DAG production by Ang II. In contrast, sustained TRPC6 activation by OAG does not require PIP2 as a DAG precursor. We investigated whether there is evidence for close association between PIP2 and TRPC6 proteins using co-immunoprecipation and Western blotting and whether association is altered in the presence of Ang II, OAG and wortmannin.

Figure 4Da illustrates that tissue lysates from mesenteric artery immunoprecipitated with anti-PIP2 and then blotted with anti-TRPC6 antibodies displayed a band of ∼110 kDa which is the expected molecular weight for TRPC6 proteins. Complementary studies showed that association between TRPC6 and PIP2 could be obtained using anti-TRPC6 for immunoprecipitation and anti-PIP2 for blotting (data not shown). Figure 4Da also shows that incubation with 1 nm Ang II, 10 μm OAG and 20 μm wortmannin for 15 min before tissue lysis all reduced the association of TRPC6 proteins with PIP2. Moreover, Fig. 4Db shows that wortmannin reduced, whereas Ang II and OAG had little effect, on total tissue PIP2 levels detected with Western blotting. Figure 4Da and c illustrates that wortmannin, Ang II and OAG had no effect on expression levels of β-actin or TRPC6.

Discussion

The present data clearly show that in addition to acting as a precursor of DAG production endogenous PIP2 also inhibits native TRPC6 channel activity in rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes. Morever, PIP2 imposes a brake on TRPC6 activation by both Ang II and DAG. This latter result represents a novel physiological role for this important phospholipid in vascular smooth muscle excitation and may suggest that DAG activates TRPC6 channels by reducing this inhibitory action of PIP2 on channel proteins.

DiC8-PIP2 inhibited Ang II-evoked whole-cell curents and TRPC6 channel currents in inside-out patches. Moreover, DiC8-PIP2 also inhibited OAG-induced TRPC6 activity in inside-out patches with an IC50 of 7.6 μm, which is comparable to the affinity of PIP2 binding to K+ channels (Zhang et al. 2003) and to fusion proteins composed of TRPC6 C-termini (Kwon et al. 2007). Anti-PIP2 antibodies initially increased TRPC6 activity induced by Ang II, which is likely to be caused by removal of an inhibitory action of endogenous PIP2. In the continued presence of anti-PIP2 antibodies, Ang II-induced TRPC6 activity was greatly reduced, which presumably reflects a reduction in PIP2 required to produce endogenous PLC-mediated DAG production and TRPC6 opening. This is consistent with Ang II-evoked TRPC6 activity being almost completely blocked by U73122, a PLC inhibitor, indicating a pivotal role for PLC in the transduction pathway (Saleh et al. 2006). Predictably, anti-PIP2 antibodies only potentiated OAG-evoked TRPC6 activity because OAG acts downstream of PLC-mediated PIP2 hydrolysis. It has been shown that PIP2 binds to expressed TRPC6 proteins in HEK293 cells (Tseng et al. 2004) and to fusion proteins composed of TRPC6 C-termini (Kwon et al. 2007), and the present co-immunoprecipitation work also shows that endogenous PIP2 associates with native TRPC6 proteins in unstimulated tissue lysates. The mechanism(s) by which anti-PIP2 antibodies prevent the inhibitory action of PIP2 is unknown. However, it is likely that recycling of PIP2 means that this phospholipid can be free or bound to TRPC6. Therefore, a simple explanation is that the free PIP2–anti-PIP2 antibody complex binds less readily to TRPC6 and is less readily hydrolysed by PLC.

Further evidence for an inhibitory action of endogenous PIP2 on TRPC6 activity is that wortmannin, LY294002 and poly-l-lysine, which all deplete PIP2 levels, produced activation of TRPC6 channels in unstimulated myocytes. In mesenteric artery myocytes there is likely to be constitutive production of DAG because an inhibitor of DAG lipase, which is the main pathway for metabolism of DAG in smooth muscle (Severson & Hee-Cheong, 1989), activates TRPC6 channels (Saleh et al. 2006). It is likely that wortmannin and LY294002 evoked TRPC6 activity by inhibiting PI-4-kinases which produces a reduction in PIP2 synthesis (Suh & Hille, 2005) due to recycling of this phospholipid. Thus leading to removal of its inhibitory action, and channel opening by constitutive generation of DAG. The transient nature of the excitatory effects of wortmannin and LY294002 is also consistent with the idea that opening of TRPC6 channels requires PIP2-mediated DAG production. Therefore, depletion of PIP2 will lead eventually to reduced DAG production and channel activation. Indeed, co-immunoprecipitation studies showed that wortmannin reduced both the association of PIP2 with TRPC6 proteins and PIP2 levels in unstimulated tissue lysates. Wortmannin also produced transient TRPC6 activity and greatly reduced noradrenaline-evoked TRPC6 currents in portal vein indicating that PIP2 may have a similar action on TRPC6 in this preparation (Aromolaran et al. 2000; Inoue et al. 2001).

As expected, wortmannin reduced Ang II-evoked TRPC6 activity, which correlated with depletion of tissue PIP2 levels and decreased association between PIP2 and TRPC6 proteins demonstrated by Western blotting and co-immunoprecipitation. A notable result was that in the presence of wortmannin, OAG-evoked TRPC6 activity in cell-attached patches was enhanced by about 50-fold, whereas OAG-induced TRPC6 activity in inside-out patches was only increased 2-fold by an anti-PIP2 antibody. These differences in potentiation of TRPC6 activity by depletion of PIP2 probably relate to the relative activity of OAG alone in the different patch configurations with OAG evoking much larger activity in inside-out than in cell-attached patches (see Figs 1Ba and 4Ba). These differences in stimulation of TRPC6 by OAG may suggest that in inside-out patches OAG is more effective at removing the inhibitory action of PIP2 and/or there are lower levels of PIP2 in a patch following excision. However, what is conclusive from these data is that there are opposing inhibitory effects of PIP2 and excitatory DAG actions on TRPC6 proteins.

An intriguing observation was that OAG reduced association between PIP2 and TRPC6 proteins without reducing tissue PIP2 levels. We are cautious in concluding any mechanism from these results although it is tempting to speculate that a simple model of mutual antagonism between DAG and PIP2, perhaps at a similar binding site(s), may underlie the mechanism by which TRPC6 proteins are activated by DAG via a PKC-independent mechanism. However, it is also possible that DAG may partially activate TRPC6, which in turn allows entry of Ca2+ ions leading to subsequent activation of PLC and PIP2 hydrolysis. Considerably more work including identification of mutual DAG and PIP2 binding sites within TRPC6 proteins and investigation of the role of PLC will be required to prove these possible activation mechanisms of TRPC6. Nevertheless, our data suggest that simultaneous depletion of PIP2 and production of DAG is necessary for activation of native TRPC6 activation as previously proposed for TRP channels in Drosophila (Estacion et al. 2001; Hardie, 2003).

It is not clear why our data showing that PIP2 has an inhibitory effect on native TRPC6 channels is opposite to the facilitatory response seen in expressed TRPC6 channels (Kwon et al. 2007; Lemonnier et al. 2008) although it should be noted that the work of Kwon et al. mainly focused on the role of PIP3 in regulating TRPC6 activity. Lemonnier et al. (2008) may have observed potentiation of TRPC6 activity by PIP2 through the phospholipid acting as a substrate for generation of DAG, particularly if there was an excess of expressed TRPC6 proteins compared with endogenous PIP2 levels in HEK293 cells. However, our present results may explain why pre-treatment with low doses of carbachol, which are likely to lower PIP2 levels, enhanced OAG-evoked TRPC activity expressed in HEK293 cells (Estacion et al. 2004).

In conclusion, endogenous PIP2 imposes an inhibitory action on native TRPC6 channels in mesenteric artery myocytes. Removal of this tonic inhibitory effect leads to TRPC6 channel activation indicating that PIP2 has a dual role of being a precursor for DAG production for channel activation and a direct inhibitor of the ion channel. This may represent an important novel physiological activation mechanism of native TRPC6 channels in vascular myocytes and may also be a common activation mechanism of other TRPC proteins stimulated by DAG via a PKC-independent pathway.

References

- Albert AP, Large WA. Synergism between inositol phosphates and diacylglycerol on native TRPC6-like channels in rabbit portal vein myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;552:789–795. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Large WA. Signal transduction pathways and gating mechanisms of native TRP-like cation channels in vascular myocytes. J Physiol. 2006;570:45–51. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.096875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Piper AS, Large WA. Role of phospholipase D and diacylglycerol in activating constitutive TRPC-like cation channels in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2005;566:769–780. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Pucovsky V, Prestwich SA, Large WA. TRPC3 properties of a native constitutively active Ca2+-permeable cation channel in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2006;571:361–373. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.102780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Saleh SN, Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Large WA. Multiple activation mechanisms of store-operated TRPC channels in smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2007;583:25–36. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromolaran AS, Albert AP, Large WA. Evidence for myosin light chain kinase mediating noradrenaline-evoked cation current in rabbit portal vein myocytes. J Physiol. 2000;524:853–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asteggiano C, Berberian G, Beauge L. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate bound to bovine cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger displays a MgATP regulation similar to that of the exchange fluxes. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:437–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2001.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauge L, Asteggiano C, Berberian G. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate bound to the bovine cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;976:288–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ, Muraki K, Flemming R. Non-selective cationic channels of smooth muscle and the mammalian homologues of Drosophila TRP. J Physiol. 2004;559:685–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian J, Cui J, McDonaild TV. HERG K+ channel activity is regulated by changes in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Circ Res. 2001;89:1168–1176. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacion M, Li S, Sinkins WG, Gosling M, Bahra P, Poll C, Westwick J, Schilling WP. Activation of human TRPC6 channels by receptor stimulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22047–22056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacion M, Sinkins WG, Schilling WP. Regulation of Drosophilia transient receptor potential-like (TrpL) channels by phospholipase C-dependent mechanisms. J Physiol. 2001;530:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0001m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC. Regulation of TRPC channels by lipid second messengers. Ann Rev Physiol. 2003;65:735–759. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell RA, Large WA. a1-Adrenoceptor activation of a non-selective cation current in rabbit portal vein by 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycerol. J Physiol. 1997;499:417–428. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Okada T, Onoue H, Hara Y, Shimizu S, Naitoh S, Ito Y, Mori Y. The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular α1-adrenoceptor-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circ Res. 2001;88:325–332. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y, Hofmann T, Montell C. Integration of phosphoinositide- and calmodulin-mediated regulation of TRPC6. Mol Cell. 2007;25:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA. Receptor-operated Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channels in vascular smooth muscle: a physiologic perspective. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:493–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier L, Trebak M, Putney JW., Jr Complex regulation of the TRPC3, 6 and 7 channel subfamily by diacylglycerol and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Cell Calcium. 2008;43:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou HH, Zhou SS, HuAng CL. Regulation of ROMK1 channel by protein kinase A via a phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5820–5825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Bandyopadhyay BC, Singh BB, Groscher K, Ambudkar IS. Molecular analysis of a store-operated and 2-acetyl-sn-glycerol-sensitive non-selective cation channel. Heteromeric assembly of TRPC1-TRPC3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21600–21606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma HP, Saxena S, Warnock DG. Anionic phospholipids regulate native and expressed epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7641–7644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuguro K, TAng J, TAng Y, Xiao R, Freichel M, Tsvilovskyy V, Ito S, Flockerzi V, Zhu M, Zholos AV. Isoform-specific inhibition of TRPC4 channel by phosphatidylinositol 4.5-bisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10026–10036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707306200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Albert AP, Saleh SN, Large WA. Endothelin-1 activates a Ca2+-permeable cation channel with TRPC3 and TRPC7 properties in rabbit coronary artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2007;580:755–764. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pian P, Bucchi A, Robinson RB, Siegelbaum SA. Regulation of gating and rundown of HCN hyperpolarization-activated channels by exogenous and endogenous PIP2. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:593–604. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohacs T. Regulation of TRP channels by PIP2. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:753–762. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh SN, Albert AP, Peppiatt CM, Large WA. Angiotensin II activates two cation conductances with distinct TRPC1 and TRPC6 channel properties in rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2006;577:479–495. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson DL, Hee-Cheong M. Diacylglycerol metabolism in isolated aortic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1989;256:C11–C17. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.1.C11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sours S, Du J, Chu S, Ding M, Zhou XJ, Ma R. Expression of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) proteins in human glomerular mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1507–F1515. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00268.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B-S, Hille B. Regulation of ion channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng PH, Lin HP, Hu H, Wang C, Zhu MX, Chen CS. The canonical transient receptor potential 6 channel as a putative phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive calcium entry system. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11701–11708. doi: 10.1021/bi049349f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T, Nilius B. Modulation of TRPs by PIPs. J Physiol. 2007;582:939–944. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LH, Johm SA, Ribalet B, Weiss JN. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) regulation of strong inward rectifier Kir2.1 channels: multilevel positive cooperativity. J Physiol. 2008;586:1833–1848. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue G, Malik B, Yue G, Eaton DC. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) stimulates epithelial sodium channel activity in A6 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11965–11969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Cracium LC, Mirshahi T, Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Jin T, Logothesis DE. PIP2 activates KCNQ channels, and its hydrolysis underlies receptor-mediated inhibition of M currents. Neuron. 2003;27:963–975. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]