Abstract

The rewarding effects of cocaine have been reported to occur within seconds of administration. Extensive evidence suggests that these actions involve the ability of cocaine to inhibit the dopamine (DA) transporter. We recently showed that 1.5 mg/kg intravenous (i.v.) cocaine inhibits DA uptake within 5 sec. Despite this evidence there remains a lack of consensus regarding how quickly i.v. cocaine and other DA uptake inhibitors elicit DA uptake inhibition. The current studies sought to better characterize the onset of cocaine-induced DA uptake inhibition and to compare these effects to those obtained with the high-affinity, long-acting DA transporter inhibitor, 1-(2-bis(4-fluorphenyl)-methoxy)-ethyl)-4-(3-phenyl-propyl)piperazine (GBR-12909). Using in vivo fast scan cyclic voltammetry, we showed that i.v. cocaine (0.75, 1.5, and 3.0 mg/kg) significantly inhibited DA uptake in the nucleus accumbens of anesthetized rats within 5 sec. DA uptake inhibition peaked at 30 sec and returned to baseline levels in approximately one hour. The effects of cocaine were dose-dependent, with the 3.0 mg/kg dose producing greater uptake inhibition at the early time points and exhibiting a longer latency to return to baseline. Further, the blood-brain barrier impermiant cocaine-methiodide had no effect on DA uptake or peak height, indicating that the generalized peripheral effects of cocaine do not contribute to the CNS alterations measured here. Finally, we show that GBR-12909 (0.75, 1.5, and 3.0 mg/kg) also significantly inhibited DA uptake within 5 sec post-injection, although the peak effect and return to baseline were markedly delayed compared to cocaine, particularly at the highest dose. Combined, these observations indicate that the central effects of dopamine uptake inhibitors occur extremely rapidly following i.v. drug delivery.

Keywords: nucleus accumbens, onset, cocaine methiodide, fast scan cyclic voltammetry, rat

The subjective effects of cocaine have been reported to begin within seconds of administration (Seecof and Tennant 1986; Evans et al., 1996; Zernig et al., 2003). Although it is well established that cocaine increases extracellular dopamine (DA) via inhibitory actions on the DA transporter (DAT), it remains unclear whether there is a direct relationship between DAT blockade and the rapid subjective reinforcing affects of cocaine (Koob and Bloom, 1988; Kuhar et al., 1991; Wise et al., 1995; Volkow et al., 1997). Slow and long-acting DAT inhibition has been associated with poor reinforcing effects, while rapid and short-acting DAT inhibition has been associated with higher addiction liability (Quinn et al., 1997; Zernig et al., 2003; Samaha et al., 2004). Therefore, determining the precise temporal profile of the neural actions responsible for the early effects of both short- (cocaine) and long-acting (1-(2-bis(4-fluorphenyl)-methoxy)-ethyl)-4-(3-phenyl-propyl) piperazine; GBR-12909) DAT inhibitors would contribute to our understanding of addiction processes.

Behavioral and neurochemical estimates of the time-course of DA transporter inhibitor effects on DA uptake in animal models vary widely. For example, in vivo microdialysis studies report that intravenous (i.v.) cocaine elevates DA levels approximately 2–5 min following injection (Pettit and Justice 1989; Wise et al., 1995; Hemby et al., 1997; Ahmed et al., 2003). Electrophysiological studies, however, demonstrate that DA neurons within the ventral tegmental area (VTA) are inhibited within a minute of i.v. cocaine administration, due to increased extracellular DA levels, activation of DA autoreceptors (Pitts and Marwah, 1987; Einhorn et al., 1988; Batsche et al., 1992; Hinerth et al., 2000), and possibly DA-independent, local anesthetic effects of cocaine (Kiyatkin and Rebec, 2000). Further, a recent publication suggests that the initial effects of i.v. cocaine on DA-induced striatal neuronal responses occur approximately 5 min after i.v. administration (Wakazono and Kiyatkin, 2008).

One study employing fast scan cyclic voltammetry (voltammetry), a rapid DA sampling technique, in conjunction with exogenously applied DA, reported that i.v. cocaine began inhibiting DA uptake in approximately 2 min (Kiyatkin et al., 2000). Our own previous voltammetry measurements, however, showed that 1.5 mg/kg cocaine produced rapid DA uptake inhibition that occurred within a matter of a few seconds (Mateo et al., 2004). Our studies employed electrical stimulation of DA cell bodies in the VTA to produce action potential-mediated release of endogenous DA. This latter approach takes full advantage of the rapid sampling rates (100 ms) allowed by voltammetry and provides the temporal resolution necessary to evaluate changes in DA release and uptake across short time periods.

GBR-12909 is a high-affinity DA uptake inhibitor that displays moderate reinforcing properties (Andersen, 1989; Howell and Byrd, 1991; Roberts, 1993; Nakachi et al., 1995; Wojnicki and Glowa, 1996; Stafford et al., 2001; Desai et al., 2005). To date, the onset of i.v. GBR-12909 effects on DA uptake inhibition have received limited attention. In vivo microdialysis studies demonstrate an increase in extracellular DA within 20 minutes of i.v. GBR-12909 with maximal levels reached within 40–60 min (Baumann et al., 1994; Nakachi et al., 1995; Engberg et al., 1997). In addition, electrophysiological studies suggest that GBR-12909 modestly inhibits VTA firing within 1 min of administration, which is similar to the time-course observed for cocaine-induced DA neuron inhibition (Hinerth et al., 2000). By comparison, a larger number of studies have examined the effects of i.p. GBR-12909 (Nash and Brodkin, 1991; Rothman et al., 1991; Budygin et al., 2000). For example, in one study comparing neurochemical measures of DA signaling, GBR-12909 produced modest elevations in extracellular DA levels, as measured by microdialysis, within 20 min of administration, whereas voltammetry measures showed an effect within 10 min (Budygin et al., 2000). Despite these observations, however, it remains unclear how rapidly GBR-12909 begins to inhibit the DAT.

To better characterize the onset of both short- and long-acting DAT inhibitors, the current studies used in vivo fast scan cyclic voltammetry to examine the dose-response effects of i.v. cocaine (0.75, 1.5, and 3.0 mg/kg) and GBR-12909 (0.75, 1.5, 3.0 mg/kg) on DA signaling within the nucleus accumbens (NAc) of anesthetized rats. Electrically stimulated DA release and uptake parameters were measured at several time points, including 5 sec, 30 sec, and 60 sec post i.v. injection of cocaine. Additionally, to control for generalized peripheral actions of cocaine, we examined the effects of cocaine methiodide, a quaternary cocaine analog that does not cross the blood-brain barrier yet elicits many of the sympathoexcitatory effects of cocaine, on DA signaling in the NAc (Shriver and Long, 1971; Hemby et al., 1994; Dickerson et al., 1999).

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g) were housed two per cage on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All protocols and animal care procedures were in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23, revised 1996), and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Wake Forest University Health Sciences.

Surgery

On the day of testing, rats were anesthetized with urethane (1.5 g/kg, i.p.) and were implanted with a Silastic® cannula (0.012" inner and 0.025" outer diameter) into the right jugular vein. Rats were subsequently placed in a stereotaxic apparatus and holes were drilled over the NAc (+1.3 A, ±1.3 L, −6.5 V), the ipsilateral VTA (−5.6 A/P, ±1.0 L, −7.5 V), and contralaterally over superficial cortex (+1.0 A, ±1.0 L, −2.5 V), where the working, stimulating, and Ag/AgCl reference electrodes were positioned, respectively. The stimulating electrode was lowered in 100 µm increments until a robust signal was recorded in the core of the NAc.

VTA Electrical stimulation

Previous observations indicate a strong correlation between the effects of cocaine on electrically stimulated DA release and uptake in anesthetized rats and unstimulated, spontaneous DA release and uptake events measured in freely moving rats (Wightman et al., 2007). Consequently, the current studies utilized electrical stimulation of the VTA to elicit action potential-mediated DA release in NAc core. The stimulating electrode was a bipolar electrode with 0.2 mm-diameter tips, separated laterally by approximately 1.5 mm (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA). Electrical stimulation was computer-generated and synchronized with voltammetry data acquisition. DA release was evoked by stimulation with 60 biphasic rectangular pulses (2 ms/phase), delivered at 60 Hz, with an amplitude of 120 µA. The protocol for assessing the effects of drug on electrically evoked DA release was as follows; i.v. injection of drug or saline as a rapid experimenter-delivered bolus over a 2 sec period, followed by a stimulus train delivered to the VTA 5 sec following completion of the injection. After the initial stimulation, trains were delivered at 30 and 60 sec, and then every 5 min thereafter for approximately 1 hr.

Electrochemistry

Carbon fiber electrodes were prepared as described previously (Cahill et al., 1996). The electrode potential was linearly scanned from −0.4 to 1.2 and back to −0.4 V vs Ag/AgCl. Cyclic voltammograms were recorded at the carbon fiber electrode every 100 ms at a scan rate of 400 V/s using a voltammeter/amperometer (Chem-Clamp, Dagan Corporation, MN). The analog output of the voltammeter was digitized (Labview, National Instruments, Austin, TX) and stored as computer files. The extracellular concentration of DA was obtained by comparing the current at the peak oxidation potential for DA (typically 500 – 700 mV) in consecutive voltammograms with electrode calibrations of known concentrations of DA (1 – 10 µM) performed at the end of the experiment. In figure 1, the rising phase of the DA signal represents a combination of DA release during the stimulus pulses and uptake during the time between pulses. The descending portion of the overflow curves represents the rate of DA uptake.

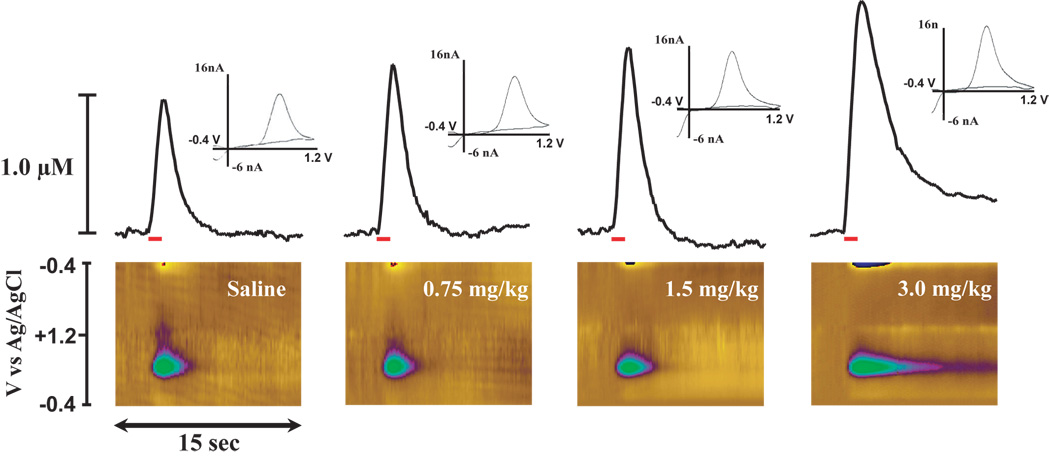

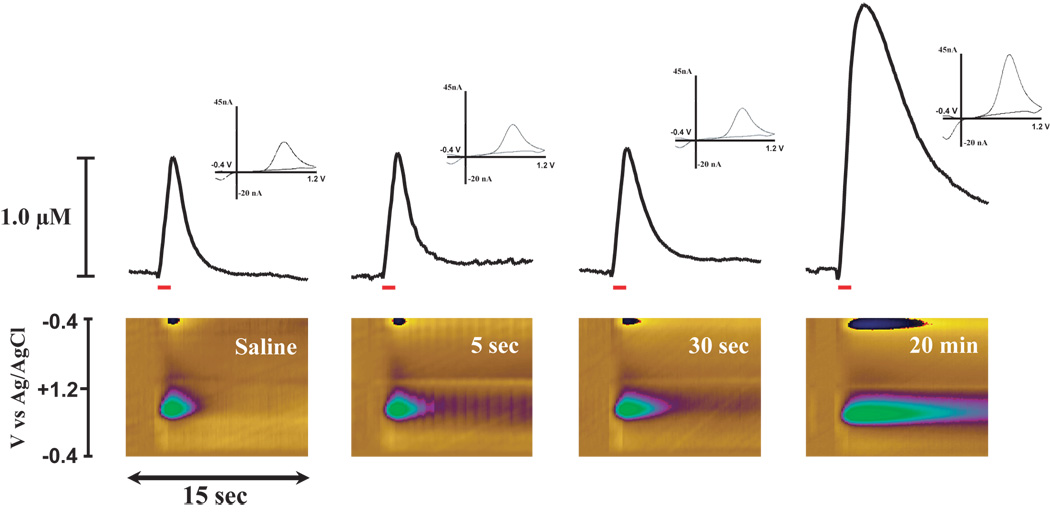

Figure 1.

Significant DA uptake inhibition within 5 sec of i.v. cocaine. Shown are representative concentration-time plots (top), color plots (bottom) and cyclic voltammograms (insets) of DA responses from representative rats following saline (left), 0.75 mg/kg, (left middle), 1.5 mg/kg, (right middle), and 3.0 mg/kg cocaine (right) injections. Concentration–time plots; electrical stimulation of VTA (60 Hz for 1 sec; red bar) rapidly induced DA release in the NAc. Relative to saline injection, i.v. cocaine elicits robust uptake inhibition, (descending portion of the curve is less steep than prior to cocaine). Color plots; the voltammetric current (displayed in color in the z-axis) is plotted against the applied potential (y-axis) and the acquisition time (x-axis). Relative to saline, cocaine increased electrically evoked release of DA and inhibited DA uptake as shown by an increase in oxidative current (plotted as green on color plots). Inset; background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms depict two current peaks, one at 600 mV (positive deflection) for DA oxidation and one at −200 mV (negative deflection) for reduction of DA-o-quinone. The position of the peaks identifies the substance oxidized as DA.

Drugs and infusion procedures

Baseline DA response parameters were collected in 5 min intervals for a minimum of 30 min. Once a stable baseline of three consecutive collections was obtained, rats received a 2 sec i.v. bolus of saline (0.9%, 0.6 ml/kg). In this case, one DA response was acquired at 5 sec post-injection, and this was subsequently used as the control saline time point for data analysis (see statistics). Five minutes after the saline injection, rats received a 2 sec, ~200 µL i.v. bolus of cocaine (0.75 mg/kg n=8, 1.5 mg/kg n=8, and, 3.0 mg/kg n=8), cocaine methiodide (1.97 mg/kg n=6) or GBR-12909 (0.75 mg/kg n=5, 1.5 mg/kg n=5, and, 3.0 mg/kg n=7). Further, to verify that saline injections alone did not produce changes in DA response parameters over the time-course of the experiment, a separate set of animals received i.v. saline injections without an ensuing drug injection (n=6). DA response parameters were acquired at 5 sec, 30sec, and 60 sec post injection and every 5 min thereafter for a minimum of 1 hr or until DA peak height and uptake parameters returned to baseline levels. In some experiments individual rats received multiple drug treatments within an experimental session. In these cases, a saline injection was given prior to each drug treatment and drug injections were given a minimum of 1 hr apart or after DA peak height and uptake parameters returned to baseline levels. Cocaine hydrochloride and cocaine-methiodide were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Rockville, MD). GBR-12909 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, (Saint Louis, MO). All drugs were dissolved in 0.9% saline.

Data analysis

DA uptake and peak height parameters were derived from voltammetric recordings of electrically evoked DA efflux as previously described (Jones et al., 1995). Two types of neurochemical information were examined to evaluate the effects of cocaine on DA processes: magnitude of electrically evoked DA release and transporter-mediated uptake kinetics, including maximal rate (Vmax) and apparent affinity (Km). Kinetics were determined using a Michaelis–Menten-based model (Wu et al., 2001). Changes in uptake and release were obtained by setting baseline levels of Km (prior to drug administration) to 0.16 µM for all rats and establishing a baseline Vmax individually for each rat and then holding it constant for the entirety of the experiment. Thus, changes in uptake parameters described in these studies are attributable to changes in Km.

Statistics

All data were log transformed to account for non-normality and unequal variance of scores. To verify that baseline conditions were stable and that saline injections did not inhibit DA uptake or alter DA peak height a one-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted for all drug treatments with time (baseline vs. saline time points) as the repeated measures variable. To examine the rapidity of cocaine-induced alterations in DA uptake and peak height, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted with dose (0.75, 1.5, or 3.0 mg/kg cocaine) as the between subjects variable and time (saline vs. 5 sec) as the repeated measures variable. When statistical significance was indicated (P < 0.05), simple effect analyses for each dose of cocaine were conducted to compare DA uptake parameters between the 5 sec, 30 sec, and 60 sec time points and the saline control time point using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA with time as the repeated measures variable. Additionally, dose-dependent differences at the 5 sec, 30sec, and 60 sec time points were assessed using one-way, between-subjects ANOVAs with cocaine dose as the between-subjects variable.

For examination of the overall time-course in DA responses following cocaine administration a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted with treatment (saline 0.6 ml/kg; 0.75, 1.5, and 3.0 mg/kg cocaine) as the between subjects variable and time (saline, 5 sec, 30 sec, 60 sec, 5 – 60 min post cocaine infusion) as the repeated measures variable.

Analyses for the cocaine-methiodide experiments were conducted using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with treatment (saline 0.6 ml/kg, cocaine methiodide 1.97 mg/kg - equimolar, cocaine 1.5 mg/kg) as the between subjects variable and time (saline, 5 sec, 30 sec, 60 sec, 5 – 60 min post cocaine infusion) as the repeated measures variable. When statistical significance was indicated (P < 0.05), simple effect analyses were conducted to compare the overall time-coursein DA responses between groups using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA as the between subjects variable and time (saline, 5 sec, 30 sec, 60 sec, 5 – 60 min post cocaine infusion) as the repeated measures variable. Additional analyses were conducted to compare DA uptake parameters between the 5 sec, 30sec, and 60 sec time points and the saline control time point using one-way, repeated measures ANOVAs with time as the repeated measures variable.

Analyses for the GBR-12909 experiments were conducted using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with dose (0.75, 1.5, or 3.0 mg/kg GBR-12909) as the between subjects variable and time (saline vs. 5 sec) as the repeated measures variable. When statistical significance was indicated (P < 0.05), simple effect analyses for each dose of GBR-12909 were conducted to compare DA uptake parameters between the 5 sec, 30 sec, and 60 sec time points and the saline control time point using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA with time as the repeated measures variable. Dose-dependent differences at the 5 sec, 30sec, and 60 sec time points were assessed using a one-way, between-subjects ANOVAs with cocaine dose as the between-subjects variable. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Cocaine produced rapid-onset DA uptake inhibition

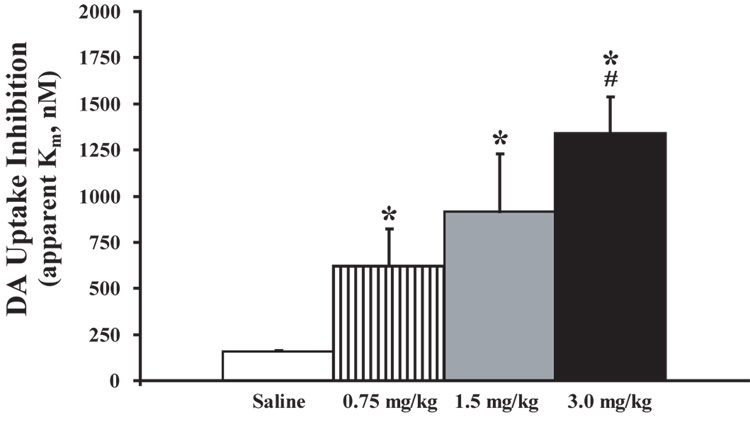

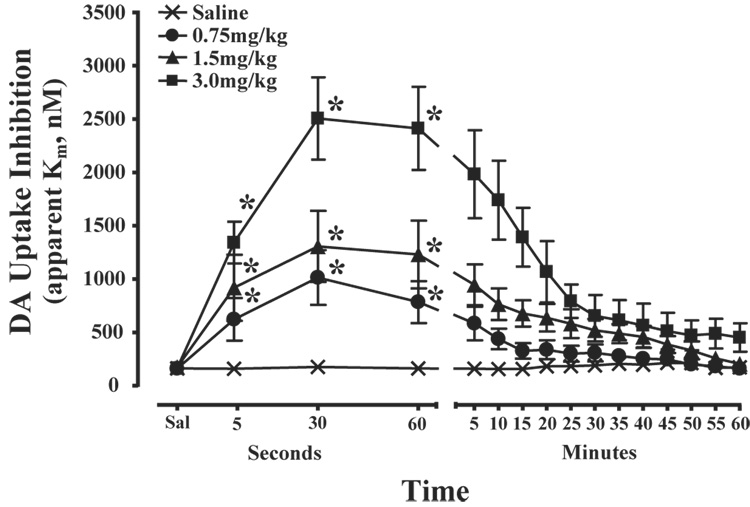

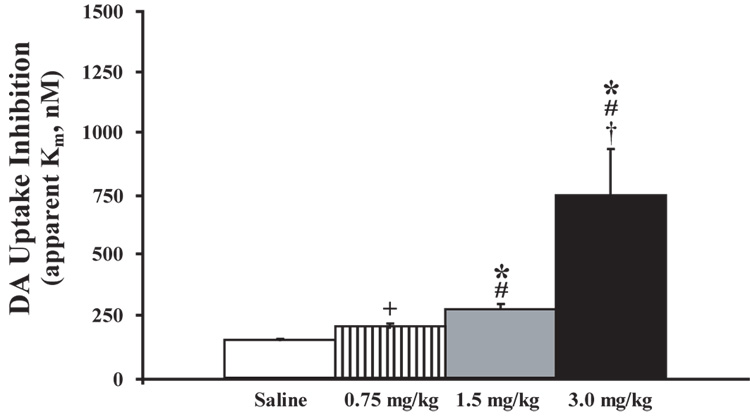

To assess the rapidity of cocaine’s actions on the DAT, the effects of cocaine on electrically evoked DA uptake and peak height were measured within the NAc of rats receiving a 2 sec, i.v. bolus of cocaine (0.75 mg/kg n=8, 1.5 mg/kg n=8, and 3.0 mg/kg n=8) or saline (0.6 ml/kg n=6). Prior to saline or drug administration, electrically evoked DA uptake and peak height parameters were stable and remained at baseline levels following saline injections (uptake, F(1,29) = 0.86, P < 0.36; peak height (F(1,29) = 0.2, P < 0.9). By comparison, relative to the saline time point, cocaine inhibited DA uptake within 5 sec of injection (time, F(1,23) = 70.7, P < 0.001). Figure 1 shows representative DA overflow curves, cyclic voltammograms, and current-time-voltage plots for each cocaine dose at 5 sec post-injection. Additional analyses indicated that, relative to the saline time point, cocaine significantly inhibited DA uptake at the 30sec, and 60 sec time points in a dose-dependent manner. Figure 2 illustrates significant effects of each dose of cocaine on apparent Km measures at the 5 sec time point. In an additional set of animals, saline was administered i.v., without an ensuing cocaine injection, and resulting DA responses for the subsequent hour were compared to those obtained following cocaine. In these studies, the overall time-course of cocaine effects on DA uptake inhibition were significantly different than for saline at all doses of cocaine examined (treatment, F(3,26) = 21.4, P < 0.001; time, F(16,416) = 34.6, P < 0.001; treatment × time, F(48,416) = 5.4, P < 0.001; Figure 3). Maximal levels of uptake inhibition were reached within 30 sec of injection. The effects of cocaine on DA peak height largely mimicked those seen with DA uptake inhibition (data not shown). In all cases, DA responses to cocaine returned to baseline levels in 1 – 2 hrs (0.75 mg/kg and 1.5 mg/kg = 50–70 min, 3.0 mg/kg = 100–120 min).

Figure 2.

Cocaine dose-dependently inhibits DA uptake within 5 sec of i.v. injection. Shown are means ± SEMs for DA uptake (apparent Km). Saline injections did not produce changes in DA uptake. DA uptake was significantly decreased 5 sec after i.v. cocaine injections. *P<0.01 relative to saline injections. #P<0.01 relative to 0.75 mg/kg cocaine.

Figure 3.

Time-course of cocaine effects on DA uptake. Shown are the mean ± SEM of DA uptake inhibition (apparent Km) for the hour following saline and cocaine (0.75 mg/kg, 1.5 mg/kg, and 3.0 mg/kg). Saline injections did not produce changes in DA uptake. By comparison, all doses of cocaine significantly inhibited DA uptake within 5 sec and maximal levels of inhibition were observed within 30 sec. These effects were maintained through much of the experimental session. Note that the x-axis is divided into second (5–60 sec) and minute (5–60 min) intervals. *P<0.01 relative to saline injections.

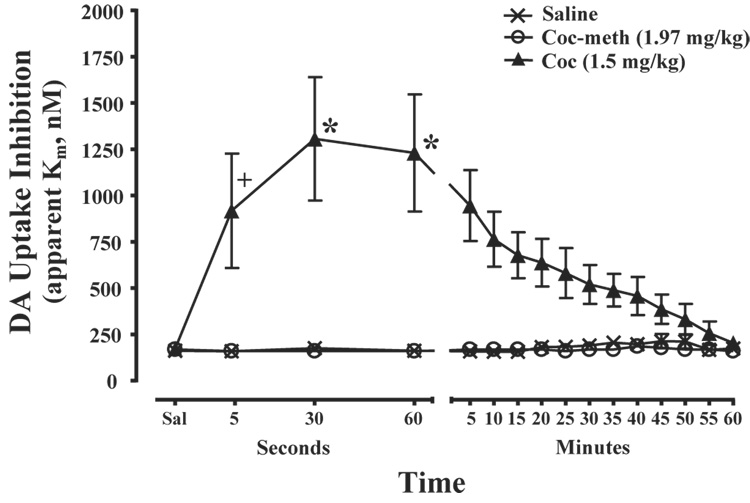

Cocaine-induced DA uptake inhibition was not dependent on peripheral actions of cocaine

To examine whether cocaine-induced DA uptake inhibition involves generalized peripheral actions of cocaine, the effects of i.v. cocaine methiodide (1.97 mg/kg - equimolar dose to 1.5 mg/kg of cocaine), a cocaine analog that does not cross the blood brain barrier yet mimics many of the sympathoexcitatory effects of cocaine (Shriver and Long, 1971; Hemby et al., 1994; Dickerson et al., 1999), were examined on DA uptake and peak height parameters. Baseline levels of electrically evoked DA uptake and peak height were stable and remained unchanged following saline injection (uptake, F(1,5) = 0.11, P = 0.75; peak height, F(1,5) = 4.54, P = 0.09). Relative to the saline time-course effects, cocaine methiodide did not significantly alter DA uptake (F(1,9) = 0.76, P = 0.41) across the experimental session (Figure 4). Additionally, consistent with the lack of effects on DA response parameters, there was a strong significant difference between the overall time course effects of cocaine-methiodide and 1.5 mg/kg cocaine (F(1,10) = 10.9, P <0.01). Further analyses indicated that these differences were significant at the 5 sec (F(1,12) = 9.4, P < 0.01), 30 sec (F(1,12) = 29.4, P < 0.001) and 60 sec (F(1,12) = 27.3, P < 0.001) time points.

Figure 4.

Cocaine-methiodide has no effect on DA uptake. Shown are the mean ± SEM of DA uptake inhibition (apparent Km) during the hour following saline, cocaine (1.5 mg/kg) and cocaine-methiodide (1.97 mg/kg). Relative to saline injections, cocaine methiodide did not produce changes in DA uptake inhibition. Consistent with this, cocaine produced significantly greater DA uptake inhibition when compared to cocaine methiodide. Note that the x-axis is divided into second (5–60 sec) and minute (5–60 min) intervals. +P<0.05, *P<0.01 relative to cocaine methiodide. Statistical significance for 1.5mg/kg cocaine vs. saline is shown in Figure 3.

GBR-12909 produced rapid-onset DA uptake inhibition

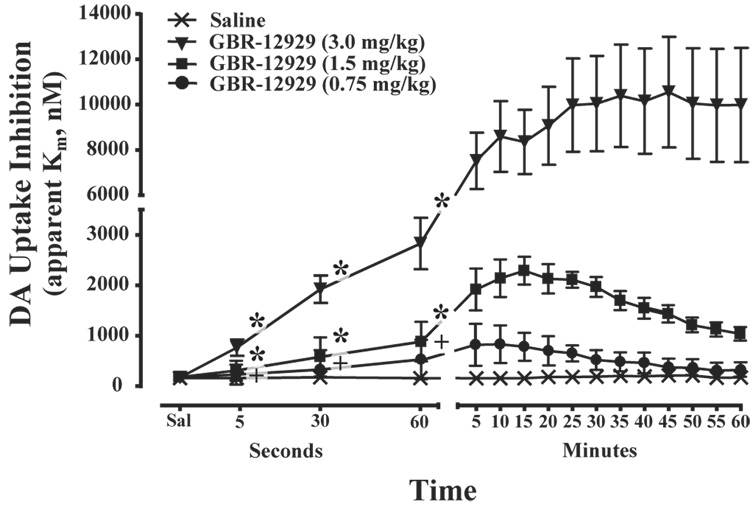

The effects of GBR-12909 on electrically evoked DA uptake and peak height were measured in the NAc of rats receiving a 2 sec, i.v. bolus of GBR-12909 (0.75 mg/kg n=5, 1.5mg/kg n=5, 3.0 mg/kg n=7). Baseline levels of electrically evoked DA uptake and peak height were stable and remained unchanged following saline injection (uptake, F(1,16) = 0.59, P = 0.45; peak height, F(1,16) = 2.7, P = 0.15). By comparison, relative to saline, across all doses, GBR-12909 significantly inhibited DA uptake (F(1,16) = 28.7, P < 0.001) within 5 sec of the injection (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Additional analyses indicated that, relative to the saline time point, GBR-12909 significantly inhibited DA uptake at the 30 sec, and 60 sec time points in a dose-dependent manner. Further, the overall time-course of GBR-12909 effects on DA uptake inhibition were significantly different than for saline at all doses of GBR-12909 examined (treatment, F(3,19) = 53.0, P < 0.001; time, F(16,304) = 79.9, P < 0.001; treatment × time, F(48,304) = 19.1, P < 0.001; Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Significant DA uptake inhibition within 5 s of i.v. GBR-12909 administration. Shown are representative concentration/time plots (top), color plots (bottom) and cyclic voltammograms (insets) of DA responses from representative rats following saline injection (left) and 5 sec (left middle), 30 sec (right middle), and 20 min (right) after GBR-12909 injection. Concentration–time plots; relative to saline injection, i.v. GBR-12909 elicited modest yet significant uptake inhibition at the 5 sec and 30 sec time points and robust uptake inhibition and increased DA peak height at the 20 min time point. Color plots; the voltammetric current (displayed in color in the z-axis) is plotted against the applied potential (y-axis) and the acquisition time (x-axis). Relative to saline, GBR-12909 increased DA uptake inhibition and increase peak height as shown by an increase in oxidative current (plotted as green on color plots). This effect was the most robust at the 20 min time point. Inset; background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms depict two current peaks, one at 600 mV (positive deflection) for DA oxidation and one at −200 mV (negative deflection) for reduction of DA-o-quinone. The position of the peaks identifies the substance oxidized as DA.

Figure 6.

GBR-12909 dose-dependently inhibits DA uptake within 5 sec of i.v. injection. Shown are means ± SEMs for DA uptake (apparent Km). Saline injections did not produce changes in DA uptake. In contrast, DA uptake was significantly decreased 5 sec after i.v. GBR-12909 injections. +P<0.05, *P<0.01 relative to saline. #P<0.01, relative to 0.75 mg/kg GBR-12909. †P<0.01 relative to 1.5 mg/kg GBR-12909.

Figure 7.

Time-course effects of GBR-12909 on DA uptake. Shown are the mean ± SEM of DA uptake inhibition (apparent Km) for the hour following saline and GBR-12909 (0.75 mg/kg, 1.5 mg/kg, and 3.0 mg/kg). Relative to saline injections, GBR-12909 produced marked inhibition of DA uptake as early as 5 sec following i.v. administration. Maximal levels were reached in approximately 20 min. Note that the y-axis is divided to show the full range of apparent Km values and that the x-axis is divided into second (5–60 sec) and minute (5–60 min) intervals. +P<0.05, * P<0.01 relative to saline.

Discussion

The current studies demonstrate that i.v. cocaine elicits robust, dose-dependent DA uptake inhibition within 5 sec of injection. Maximal levels of uptake inhibition were observed within 30 sec of injection and returned to baseline levels in approximately 1 hr. This effect of cocaine on DA uptake followed a similar time course to the brain levels of cocaine measured by PET imaging in humans and baboons (Fowler et al., 1989; Fowler et al., 1998).

Previous neurochemical studies have indicated that i.p. administration of GBR-12909 elicits a slow onset of DAT inhibition (Budygin et al., 2000). In the current studies, we examined the onset of DA uptake inhibition following i.v. delivery of GBR-12909. Similar to that observed with cocaine, GBR-12909 also inhibited DA uptake within 5 sec following i.v. injection, although the initial effects were more modest, and peak effects were larger and markedly delayed (compare Figure 2 and Figure 6). We postulate that the differences in time-course between cocaine and GBR-12909 are related to pharmacokinetic factors, including lipophilicity and transport across the blood-brain barrier. Given that GBR-12909 has been considered to be a slow-onset, long-acting DAT inhibitor, the novel measurement of the rapid onset of DA uptake inhibition following i.v. delivery in our studies suggests that it is not a unique property of cocaine to enter the brain quickly and begin inhibiting the DAT within seconds of i.v. drug administration.

The prevailing dogma that high-affinity and long-acting drugs have slow-onset kinetics and are thus associated with lower abuse liability may not apply to i.v. administration, particularly given that i.v. GBR-12909 supports self-administration in several animal models (Howell and Byrd, 1991; Roberts, 1993; Wojnicki and Glowa, 1996; Stafford et al., 2001). Based on our observations with GBR-12909, i.v. administration of similar drugs could produce rapid DA uptake inhibition, and thus could have strong reinforcing effects. Although our data suggest that the initial effects of GBR-12909 are slightly less robust than that observed with cocaine, the initial effects of this high-affinity and long-acting DAT inhibitor occur on the same time scale as cocaine. Thus the overall effects of GBR-12909 include a similar rapid initial DA uptake inhibition relative to cocaine, with greater maximal and longer lasting effects on DA uptake.

The effect of cocaine on DA responses does not appear to involve peripheral or indirect actions of this drug. First, the exclusively peripheral effects of cocaine methiodide, which have previously been shown to elicit many of the sympathoexcitatory effects of cocaine (Tessel et al., 1978; Dickerson et al., 1999), failed to mimic the actions of cocaine on DA uptake inhibition. This indicates the likelihood that peripheral actions of cocaine are not primarily responsible for the rapid onset of DA uptake inhibition observed in these studies. Second, the rapid sampling rate of voltammetry allows for the temporal separation of release and uptake components of DA efflux. In the current studies, best-fit kinetic parameters indicated that uptake of DA through the DAT was inhibited within 5 sec of i.v. cocaine administration, separately from any possible release effects that could be attributed to indirect actions of cocaine on DA neuronal firing rates.

The current studies used urethane-anesthetized rats to avoid anesthesia-induced alterations in DA uptake kinetics that can occur when using other anesthetics (Greco and Garris, 2003), and to maintain a faithful representation of DA responses to DA uptake inhibitors, which affect uptake in the same manner in both freely moving and urethane-anesthetized rats (Greco and Garris, 2003; Wightman et al., 2007). Further, the use of anesthetized rats affords the ability to examine the effects of various drugs without potential interference from known behavioral influences on DA (e.g., increased behavioral activity or stress) that can occur when using freely moving animals. Consequently, the current observations provide an accurate examination of cocaine actions on DA uptake without involvement of potential confounding influences of behavioral or state-dependent factors that might independently modulate DA neurotransmission.

The current results are consistent with previous observations demonstrating relatively rapid central actions of cocaine. For example, using PET imaging of the baboon striatum, Fowler and colleagues demonstrated measurable, albeit modest, DAT occupancy at the earliest time point sampled (1 min) following 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg/kg i.v. cocaine (Fowler et al., 1998). Additionally, in a rat amperometry study, cocaine (2.0 mg/kg i.v) inhibited DA uptake within 20 sec of injection (Samaha et al., 2004). Further, increased extracellular DA levels were observed during a 20 sec infusion of 3.0 mg/kg cocaine using voltammetric techniques (Heien et al., 2005). Consistent with this, our previous voltammetry observations indicated robust DA uptake inhibition in NAc within 3–4 seconds of 1.5 mg/kg i.v. cocaine. These effects occur on a similar timescale as the most rapid behavioral effects of cocaine in rats (Kiyatkin et al., 2000; Mateo et al., 2004). Combined with the previous studies, the current observations offer support for the hypothesis that cocaine produces rapid DA uptake inhibition and indicates that the time course of cocaine’s effects on the DAT are consistent with the rapid subjective effects of cocaine.

A limited set of previous studies have investigated the time-course of cocaine effects and suggested a potential mismatch between the rapid onset of cocaine’s actions on behavior and the relatively slower effects on DA uptake parameters. For example, using voltammetry techniques in conjunction with exogenous DA application into the NAc, Kiyatkin and colleagues (2000) reported that the behavioral activation observed within seconds of i.v. cocaine precedes DA uptake inhibition, which begins at 2 min and peaks at 6 min post-injection. Although the current findings do not concur exactly with these previous observations, the distinct conditions under which DA measurements were obtained in each of these studies may explain the apparent discrepancy observed. The central distinguishing difference between these studies involves the method employed to increase DA to detectable levels within the NAc. The current experiments used electrical stimulation of DA cell bodies in the VTA to elicit action potential-mediated release of endogenous DA, whereas the Kiyatkin et al (2000) studies utilized iontophoresis of exogenous DA into the NAc. High concentrations of exogenous DA can compromise DA transporter function by saturating plasma membrane as well as vesicular uptake and storage (Jones et al., 1999). Under these conditions the DAT transports DA in both the forward and reverse direction, which complicates kinetic analysis of uptake and may contribute to a longer latency to observe measurable changes in DA uptake inhibition.

Recently, another observation contests the rapid-onset DA uptake inhibition observed following i.v. cocaine (Wakazono and Kiyatkin, 2008). In these studies, the effects of cocaine on DA uptake were indirectly estimated by measuring the increase in magnitude of DA-induced inhibition of striatal cell firing, resulting from DAT inhibition by i.v. cocaine. Specifically, these researchers obtained baseline levels of striatal inhibition in response to iontophoretic application of DA. Following, i.v. cocaine injections, exogenous DA application significantly decreased the activity of striatal neurons beyond baseline levels after 9 min, with peak inhibition observed after approximately 15 min. Although informative, these observations do not offer direct evidence for the effects of cocaine on DAT inhibition and instead provide information on the time-course of the postsynaptic effects of cocaine-induced increases in extracellular DA levels. Consequently, the delayed onset observed in the Wakazono and Kiyatkin studies reflects the time required for cocaine-induced accumulation of extracellular DA due to reduced DA uptake, for the resulting increased binding of DA to postsynaptic DA receptors on striatal neurons, and for the activation of second messenger systems that eventually lead to alterations in striatal firing rates.

The euphoric effects of i.v. cocaine occur within seconds of administration in humans (Seecof and Tennant 1986; Evans et al., 1996; Quinn et al., 1997; Zernig et al., 2003). Although it cannot be determined explicitly that there is a direct relationship between alterations in DAT function and the rewarding effects of cocaine, the current studies indicate that the time course of cocaine effects on DA uptake inhibition are in line with the behavioral and subjective effects of this drug when taken i.v.. Consequently, despite previous work suggesting a mismatch between the central and behavioral effects of cocaine, the present observations offer a reconciliation of the timing of behavioral and neurochemical cocaine effects. Further, these observations also indicate a similarly rapid initial effect of GBR-12909 on DA uptake inhibition. Combined, these observations suggest that following i.v. administration, both cocaine and GBR-12909 enter the brain and interact with the DAT to elicit significant uptake inhibition within a matter of seconds.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Evgeny A. Budygin and Joanne K. Konstantopoulos for their expert technical and theoretical advice. This study was supported by P50 DA06634-16 (D.C.S.R.) and RO1 DA021325 (S.R.J).

Glossary

- DA

Dopamine

- i.v.

Intravenous

- GBR-12909

1-(2-bis(4-fluorphenyl)-methoxy)-ethyl)-4-(3-phenyl-propyl)pipera zine

- DAT

Dopamine transporter

- VTA

Ventral tegmental area

- voltammetry

Fast scan cyclic voltammetry

- NAc

Nucleus accumbens

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed SH, Lin D, Koob GF, Parsons LH. Escalation of cocaine self-administration does not depend on altered cocaine-induced nucleus accumbens dopamine levels. J. Neurochem. 2003;86:102–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen PH. The dopamine inhibitor GBR 12909: selectivity and molecular mechanism of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;166:493–504. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batsche K, Granoff MI, Wang RY. 5-HT3 receptor antagonists fail to block the suppressant effect of cocaine on the firing rate of A10 dopamine neurons in the rat. Brain Res. 1992;592:273–277. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91685-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann MH, Char GU, de Costa BR, Rice KC, Rothman RB. GBR12909 attenuates cocaine-induced activation of mesolimbic dopamine neurons in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:1216–1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budygin EA, Kilpatrick MR, Gainetdinov RR, Wightman RM. Correlation between behavior and extracellular dopamine levels in rat striatum: comparison of microdialysis and fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;281:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cahill PS, Walker QD, Finnegan JM, Mickelson GE, Travis ER, Wightman RM. Microelectrodes for the measurement of catecholamines in biological systems. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:3180–3186. doi: 10.1021/ac960347d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai RI, Kopajtic TA, French D, Newman AH, Katz JL. Relationship between in vivo occupancy at the dopamine transporter and behavioral effects of cocaine, GBR 12909 [1-{2-[bis-(4-fluorophenyl)methoxy]ethyl}-4-(3-phenylpropyl)piperazine], and benztropine analogs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;315:397–404. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickerson LW, Rodak DJ, Kuhn FE, Wahlstrom SK, Tessel RE, Visner MS, Schaer GL, Gillis RA. Cocaine-induced cardiovascular effects: lack of evidence for a central nervous system site of action based on hemodynamic studies with cocaine methiodide. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1999;33:36–42. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einhorn LC, Johansen PA, White FJ. Electrophysiological effects of cocaine in the mesoaccumbens dopamine system: studies in the ventral tegmental area. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:100–112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-01-00100.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engberg G, Elverfors A, Jonason J, Nissbrandt H. Inhibition of dopamine re-uptake: significance for nigral dopamine neuron activity. Synapse. 1997;25:215–226. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199702)25:2<215::AID-SYN12>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans SM, Cone EJ, Henningfield JE. Arterial and venous cocaine plasma concentrations in humans: relationship to route of administration, cardiovascular effects and subjective effects. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;279:1345–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Pappas N, King P, Ding YS, Wang GJ. Measuring dopamine transporter occupancy by cocaine in vivo: radiotracer considerations. Synapse. 1998;28:111–116. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199802)28:2<111::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, Macgregor RR, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ. Mapping cocaine binding sites in human and baboon brain in vivo. Synapse. 1989;4:371–377. doi: 10.1002/syn.890040412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greco PG, Garris PA. In vivo interaction of cocaine with the dopamine transporter as measured by voltammetry. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;479:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heien ML, Khan AS, Ariansen JL, Cheer JF, Phillips PE, Wassum KM, Wightman RM. Real-time measurement of dopamine fluctuations after cocaine in the brain of behaving rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:10023–10028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504657102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemby SE, Co C, Koves TR, Smith JE, Dworkin SI. Differences in extracellular dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens during response-dependent and response-independent cocaine administration in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;133:7–16. doi: 10.1007/s002130050365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemby SE, Jones GH, Hubert GW, Neill DB, Justice JB. Assessment of the relative contribution of peripheral and central components in cocaine place conditioning. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1994;47:973–979. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinerth MA, Collins HA, Baniecki M, Hanson RN, Waszczak BL. Novel in vivo electrophysiological assay for the effects of cocaine and putative "cocaine antagonists" on dopamine transporter activity of substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. Synapse. 2000;38:305–312. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20001201)38:3<305::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell LL, Byrd LD. Characterization of the effects of cocaine and GBR 12909, a dopamine uptake inhibitor, on behavior in the squirrel monkey. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;258:178–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones SR, Garris PA, Kilts CD, Wightman RM. Comparison of dopamine uptake in the basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, caudate-putamen, and nucleus accumbens of the rat. J. Neurochem. 1995;64:2581–2589. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64062581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones SR, Joseph JD, Barak LS, Caron MG, Wightman RM. Dopamine neuronal transport kinetics and effects of amphetamine. J. Neurochem. 1999;73:2406–2414. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0732406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiyatkin EA, Kiyatkin DE, Rebec GV. Phasic inhibition of dopamine uptake in nucleus accumbens induced by intravenous cocaine in freely behaving rats. Neuroscience. 2000;98:729–741. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiyatkin EA, Rebec GV. Dopamine-independent action of cocaine on striatal and accumbal neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:1789–1800. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koob GF, Bloom FE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence. Science. 1988;242:715–723. doi: 10.1126/science.2903550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhar MJ, Ritz MC, Boja JW. The dopamine hypothesis of the reinforcing properties of cocaine. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:299–302. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90141-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mateo Y, Budygin EA, Morgan D, Roberts DC, Jones SR. Fast onset of dopamine uptake inhibition by intravenous cocaine. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:2838–2842. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakachi N, Kiuchi Y, Inagaki M, Inazu M, Yamazaki Y, Oguchi K. Effects of various dopamine uptake inhibitors on striatal extracellular dopamine levels and behaviours in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;281:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00246-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nash JF, Brodkin J. Microdialysis studies on 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced dopamine release: effect of dopamine uptake inhibitors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;259:820–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pettit HO, Justice JB. Dopamine in the nucleus accumbens during cocaine self-administration as studied by in vivo microdialysis. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1989;34:899–904. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitts DK, Marwah J. Cocaine modulation of central monoaminergic neurotransmission. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1987;26:453–461. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinn DI, Wodak A, Day RO. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles of illicit drug use and treatment of illicit drug users. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:344–400. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199733050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts DC. Self-administration of GBR 12909 on a fixed ratio and progressive ratio schedule in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;111:202–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02245524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothman RB, Mele A, Reid AA, Akunne HC, Greig N, Thurkauf A, de Costa BR, Rice KC, Pert A. GBR12909 antagonizes the ability of cocaine to elevate extracellular levels of dopamine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991;40:387–397. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90570-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samaha AN, Mallet N, Ferguson SM, Gonon F, Robinson TE. The rate of cocaine administration alters gene regulation and behavioral plasticity: implications for addiction. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:6362–6370. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1205-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seecof R, Tennant FS. Subjective perceptions to the intravenous "rush" of heroin and cocaine in opioid addicts. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1986;12:79–87. doi: 10.3109/00952998609083744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shriver DA, Long JP. A pharmacologic comparison of some quaternary derivatives of cocaine. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1971;189:198–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stafford D, Lesage MG, Rice KC, Glowa JR. A comparison of cocaine, GBR 12909, and phentermine self-administration by rhesus monkeys on a progressive-ratio schedule. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;62:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tessel RE, Smith CB, Russ DN, Hough LB. The effects of cocaine HC1 and a quaternary derivative of cocaine, cocaine methiodide, on isolated guinea-pig and rat atria. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1978;205:568–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, Fowler JS, Abumrad NN, Vitkun S, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Pappas N, Hitzemann R, Shea CE. Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nature. 1997;386:827–830. doi: 10.1038/386827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakazono Y, Kiyatkin EA. Electrophysiological evaluation of the time-course of dopamine uptake inhibition induced by intravenous cocaine at a reinforcing dose. Neuroscience. 2008;151:824–835. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wightman RM, Heien ML, Wassum KM, Sombers LA, Aragona BJ, Khan AS, Ariansen JL, Cheer JF, Phillips PE, Carelli RM. Dopamine release is heterogeneous within microenvironments of the rat nucleus accumbens. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;26:2046–2054. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wise RA, Newton P, Leeb K, Burnette B, Pocock D, Justice JB. Fluctuations in nucleus accumbens dopamine concentration during intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:10–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02246140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wojnicki FHE, Glowa JR. Effects of drug history on the acquisition of responding maintained by GBR 12909 in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 1996;123:34–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02246278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu Q, Reith ME, Wightman RM, Kawagoe KT, Garris PA. Determination of release and uptake parameters from electrically evoked dopamine dynamics measured by real-time voltammetry. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2001;112:119–133. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zernig G, Giacomuzzi S, Riemer Y, Wakonigg G, Sturm K, Saria A. Intravenous drug injection habits: drug users' self-reports versus researchers' perception. Pharmacology. 2003;68:49–56. doi: 10.1159/000068731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]