Abstract

The influence of Ca2+ binding properties of individual troponin versus cooperative regulatory unit interactions along thin filaments on the rate tension develops and declines was examined in demembranated rabbit psoas fibres and isolated myofibrils. Native skeletal troponin C (sTnC) was replaced with sTnC mutants having altered Ca2+ dissociation rates (koff) or with mixtures of sTnC and D28A, D64A sTnC, that does not bind Ca2+ at sites I and II (xxsTnC), to reduce near-neighbour regulatory unit (RU) interactions. At saturating Ca2+, the rate of tension redevelopment (kTR) was not altered for fibres containing sTnC mutants with decreased koff or mixtures of sTnC:xxsTnC. We examined the influence of koff on maximal activation and relaxation in myofibrils because they allow rapid and large changes in [Ca2+]. In myofibrils with M80Q sTnCF27W (decreased koff), maximal tension, activation rate (kACT), kTR and rates of relaxation were not altered. With I60Q sTnCF27W (increased koff), maximal tension, kACT and kTR decreased, with no change in relaxation rates. Surprisingly, the duration of the slow phase of relaxation increased or decreased with decreased or increased koff, respectively. For all sTnC reconstitution conditions, Ca2+ dependence of kTR in fibres showed Ca2+ sensitivity of kTR (pCa50) shifted parallel to tension and low-Ca2+kTR was elevated. Together the data suggest the Ca2+-dependent rate of tension development and the duration (but not rate) of relaxation can be greatly influenced by koff of sTnC. This influence of sTnC binding kinetics occurs primarily within individual RUs, with only minor contributions of RU interactions at low Ca2+.

Contraction in striated muscle is a dynamic process that is dependent on Ca2+ binding kinetics, thin filament activation, and acto-myosin crossbridge cycling. Contractile activation involves a myofilament signalling cascade initiated by Ca2+ binding to troponin C (TnC), that alters interactions between troponin subunits and tropomyosin to reveal myosin binding sites on actin. This allows for strong crossbridge formation and cycling (reviewed in Gordon et al. 2000). Mechanical tension relaxation of myofilaments occurs with Ca2+ dissociation from TnC and crossbridge detachment (reviewed in Poggesi et al. 2005). The interactive kinetics of Ca2+-dependent thin filament activation and crossbridge binding are important for determining the speed of contraction and relaxation. However, an in-depth study of how Ca2+ binding kinetics of TnC influence tension development and relaxation in skeletal muscle has not been reported.

Both steady-state tension and the rate of tension redevelopment (kTR) with a rapid release–restretch length transient vary greatly with [Ca2+] in demembranated skeletal muscle as previously demonstrated by us (Regnier et al. 1996, 1998, 1999; Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007) and others (Brenner, 1988; Metzger & Moss, 1990, 1991; Sweeney & Stull, 1990). kTR has been proposed to measure the rates of transition of crossbridges between detached or weakly attached non-tension states and strong, tension generating states (Brenner & Eisenberg, 1986; Brenner, 1988). At saturating Ca2+, kTR varies with myosin isoform (Metzger & Moss, 1990) or alterations of crossbridge cycling rate (Regnier & Homsher, 1998; Regnier et al. 1998), presumably when thin filament activation is not rate limiting. Additional evidence has shown that apparent rates of crossbridge transitions are limited at submaximal Ca2+ (Chalovich et al. 1981; Brenner, 1988). Altering the Ca2+-binding properties of skeletal TnC (sTnC) or thin filament activation have been shown to influence the Ca2+ dependence of kTR (Regnier et al. 1996, 1999; Razumova et al. 2000; Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007). Together, these data suggest that Ca2+ binding dynamics of TnC have a strong influence on tension development kinetics.

While studying kTR gives an indication of crossbridge kinetics during near-equilibrium of the thin filament, the process of Ca2+-mediated activation must be studied in a system that allows for rapid changes in [Ca2+]. Isolated skeletal myofibrils are preparations that permit the measurement of activation rate (kACT) with a rapid increase in Ca2+. kACT has been shown to be Ca2+ dependent (Tesi et al. 2002), similar to kTR, but is different to kTR because kACT includes the process of thin filament activation as well as crossbridge binding and tension generation. Further, mechanical measurements of tension using myofibril preparations also allow for the study of relaxation in the same myofibrils as activation by using a rapid decrease in Ca2+. Therefore, with this technique, both activation and biphasic relaxation can be studied under conditions of altered Ca2+ binding properties of sTnC. However, few studies (Luo et al. 2002; Piroddi et al. 2003) have been devoted to understanding the influence of TnC properties on both activation and/or relaxation kinetics.

An additional consideration in understanding activation of skeletal muscle is the influence of Ca2+-binding properties on cooperative activation of contraction. In skeletal muscle, near-neighbour regulatory unit (RU; 1 troponin + 1 tropomyosin + the number of actin monomers exposed with Ca2+ binding) interactions along the thin filament contribute greatly to the apparent cooperativity in the tension–pCa relationship (Brandt et al. 1984; Metzger & Moss, 1991; Regnier et al. 2002), but appear to have little influence on maximal kTR or the Ca2+-dependent increase in kTR (Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007). These data suggest that control of kTR is local, i.e. modulated within individual RUs in the thin filaments of skeletal muscle. However, it is not known whether sTnC Ca2+ binding kinetics can influence the thin filament activation dependence of kTR within individual RUs. It is also unknown how increased Ca2+-binding affinity of sTnC alters the Ca2+ dependence of kTR in the presence or absence of near-neighbour RU interactions.

In this study we used both single demembranated rabbit skeletal fibres and myofibrils to examine the role of altered Ca2+ dissociation rate (koff) of skeletal TnC (sTnC) on the kinetics of tension development (measured as kACT and kTR) with or without near-neighbour RU interactions and on the kinetics of relaxation. We found that with decreased koff, kTR at low tension was increased in fibres without changing maximal kTR both in the absence and presence of near-neighbour RU interactions. In skeletal myofibrils containing sTnC mutants, kACT and kTR at maximal Ca2+ were unchanged with decreased koff, but were decreased for a sTnC mutant with increased koff. Interestingly, while the rates of relaxation were unaltered, the duration of the slow phase of relaxation was increased or decreased with sTnC mutants having decreased or increased koff, respectively. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an influence of troponin Ca2+ binding kinetics on the isometric phase of relaxation. Preliminary reports of this work have been previously published (Kreutziger et al. 2004, 2006).

Methods

Fibre preparation

All animal procedures performed in the US were conducted in accordance with the US National Institutes of Health Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Washington (UW) Animal Care Committee. Rabbits were housed in the Department of Comparative Medicine at UW and cared for in accordance with UW IACUC procedures. Male New Zealand white rabbits were anaesthetized with an intravenous injection of pentobarbital (40 mg kg−1) in the marginal ear vein and when the animals had no reflexive response, were exsanguinated. The psoas muscle was exposed and small bundles of psoas fibres were excised at native length, demembranated and stored at −20°C for up to 6 weeks as previously described (Regnier et al. 2002). Segments of single fibres dissected from the fibre bundles were prepared for mechanical measurements by chemically fixing the ends with 1% gluteraldehyde in water (Chase & Kushmerick, 1988) and wrapped in aluminium foil T-clips for attachment to the mechanical apparatus.

Myofibril preparation

All animal procedures performed in Italy were conducted in accordance with the official regulations of the European Community Council on Use of Laboratory Animals (Directive 86/609/EEC) and protocols were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experiments of the University of Florence. Male New Zealand white rabbits were killed by intravenous administration of pentobarbitone (120 mg kg−1) through the marginal ear vein. The psoas muscle was exposed and small bundles of psoas fibres were excised at native length and tied to wooden sticks in ice-cold Ringer-EGTA solution, as previously described (Colomo et al. 1997). Bundles were transferred the next day to Rigor solution with 50% glycerol for 12 h, and then stored at −20°C. Myofibrils were prepared by homogenization of small pieces of glycerinated fibres in Rigor solution on ice, and used for up to 5 days as previously described (Colomo et al. 1997).

Proteins

Rabbit skeletal TnC mutations F27W, M80Q, I60Q and D28A, D64A sTnC (xxsTnC) that does not bind Ca2+ at sites I and II were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis as previously described (Regnier et al. 2002; Kreutziger et al. 2007). WT or mutant sTnC was extracted and purified from E. coli (Dong et al. 1996). All recombinant proteins were used for myofibril sTnC replacement. Native rabbit sTnC, sTnI and sTnT were purified from ether powder of rabbit skeletal back and leg muscles (Potter, 1982). Purified sTnC (called ‘sTnC’ in the text) was used in fibres as a control for the effects of extraction–reconstitution of sTnC and for comparison to recombinant mutant sTnC. Note that ‘native’ sTnC refers to protein in the muscle preparation prior to any treatment. Whole sTn complexes used for stopped-flow measurements were formed using recombinant sTnC (WT or mutant) and purified sTnI and sTnT as previously described (Szczesna et al. 2000; Kreutziger et al. 2007). sTnC concentrations were calculated from peak absorbance at 280 nm with appropriate extinction coefficients (Kreutziger et al. 2007). Purity of native and recombinant troponin subunits was assessed by SDS-PAGE.

Ca2+ solutions for mechanical measurements

Experimental solutions for fibre mechanics were calculated as previously described (Martyn et al. 1994) and contained (mm): phosphocreatine 15, EGTA 15, 3-(N-mopholino) propanesulphonic acid (Mops) 80, free Mg2+ 1, (Na++ K+) 135, ATP 5, dithiothreitol (DTT) 1, 250 units ml−1 creatine kinase (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 4% (w/v) Dextran T-500 (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA) at pH 7.0, 15°C, and an ionic strength of 0.17 m. For activating solutions, the Ca2+ level (expressed as pCa =−log [Ca2+]) was varied between pCa 9.0 and 4.0 by adjusting Ca(propionate)2 concentration. Experimental solutions for myofibril mechanics were calculated as previously described (Brandt et al. 1998) and contained (mm): phosphocreatine 10, EGTA 10 (ratio of CaEGTA/EGTA set to obtain pCa values 8.0–3.5), Mops 10, free Mg2+ 1, (Na++ K+) 155, MgATP 5, 200 units ml−1 creatine kinase, and propionate and sulphate to adjust the final solution ionic strength to 0.2 m. Contaminant phosphate (Pi) was reduced in all experiments to < 5 μm by a Pi-scavenging enzyme system (purine-nucleoside-phosphorylase with substrate 7-methyl-guanosine) as previously described (Tesi et al. 2000).

Fibre mechanical data acquisition and analysis

For all muscle fibre experiments, mechanical data were collected from fixed and clipped fibre segments attached to an Aurora Scientific (Ontario, Canada) force transducer model 400A and a General Scanning model G120DT (Watertown, MA, USA) servo-motor (adjusted for 300 μs step time) by minutien pin hooks and mounted on a Nikon (Japan) inverted microscope as previously described (Regnier et al. 2002). Sarcomere length (SL) was initially set to 2.5 μm (Lo) and continuously monitored with helium–neon laser diffraction. Average unfixed Lo of gluteraldehyde-treated fibres was 1.27 ± 0.04 mm and diameter was 55 ± 1 μm (mean ±s.e.m.; n = 50). At 5 s intervals fibre segments were shortened by 15%Lo at 10 Lo s−1, then rapidly restretched to initial Lo to maintain fibre integrity (Brenner, 1983; Sweeney et al. 1987; Chase & Kushmerick, 1988). The fibre preparation was moved between pCa solutions that were held in individual temperature-controlled troughs as previously described (Regnier et al. 2002). Measurement of steady-state isometric tension was made prior to the release–restretch transient used for measurement of kTR at each Ca2+ level. Passive tension was determined at pCa 9.0 with a 15%Lo release–restretch square-wave protocol and was subtracted from total tension measured in higher Ca2+ solutions to obtain the active tension values reported. Maximal fibre tension (Fmax) measured at pCa 4.5 just prior to sTnC extraction was 354 ± 12 mN mm−2 (mean ±s.e.m., n = 50; assuming circular cross-sectional area). Fibres with greater than 12% loss of Fmax prior to extraction were discarded. High-frequency sinusoidal stiffness was measured at steady-state tension by small-amplitude (0.05%Lo) high-frequency (1000 Hz) sinusoidal oscillations to examine changes in strong crossbridge binding as previously described (Dantzig et al. 1992).

kTR–pCa data were fitted with the Hill equation

| (1) |

using non-linear least-squares regression analysis (SigmaPlot), where kTR,max is the maximal kTR at pCa 4.5, nH is the slope of the curve (associated with the apparent cooperativity in the system), and pCa50 is the pCa value at which half-maximal kTR is obtained. Reported pCa50 values for kTR–pCa represent fits to the average data and are reported ±s.e.m. of the fits (Table 2), because fits for individual experiments were highly variable or not possible. For this reason, nH values are not reported. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare between fibre groups after reconstitution and when differences were significant, Student's paired or unpaired t tests were used with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Table 2.

kTR,max and Ca2+ sensitivity of kTR for rabbit psoas fibres reconstituted with sTnC mutants alone and in mixtures with xxsTnC

| sTnC condition (n) | kTR,max (s−1) | pCa50 of kTR |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-extracted native sTnC (50) | 14.0 ± 0.4 | 5.75 ± 0.02 |

| sTnC (7) | 13.5 ± 1.1 | 5.72 ± 0.02 |

| sTnCF27W (9) | 11.8 ± 0.4 | 5.78 ± 0.01 |

| M80Q sTnC (6) | 12.0 ± 1.2 | 5.90 ± 0.02 |

| M80Q sTnCF27W (9) | 13.2 ± 0.9 | 5.92 ± 0.03 |

| sTnC:xxsTnC (6) | 10.8 ± 1.0 | 5.29 ± 0.05 |

| M80Q sTnC: xxsTnC (6) | 10.1 ± 1.7 | 5.66 ± 0.06 |

| M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC (7) | 9.5 ± 1.4 | 5.59 ± 0.08 |

n, number of fibres. kTR,max is not different between all experimental groups by ANOVA. See Methods for curve fitting of kTR–pCa data.

Myofibril mechanical data acquisition and analysis

For myofibril experiments, mechanical data were collected from single or small bundles of skeletal myofibrils attached between two glass microtools and perfused with solution that was rapidly changed as previously described (Colomo et al. 1997, 1998; Tesi et al. 1999, 2000). Briefly, myofibrils adhered strongly to the two glass microtools, a post and a calibrated tension probe (compliance 2.9–4.9 nm nN−1; frequency response 2–3 kHz in experimental solutions). Sarcomere length (SL) was initially set 10–20% above slack length (Tesi et al. 1999) and was 2.60 ± 0.01 μm (mean ±s.e.m., n = 56) by calibrated visualization with a camera and monitor. At this SL, average myofibril Lo was 57 ± 2 μm and diameter was 2.14 ± 0.03 μm (1–4 myofibrils). Photoelectric detection of tension probe deflection was used to calculate tension. Motorized solution switching between two streams from a double-barrelled pipette and solution flow by gravity were as previously described (Tesi et al. 1999, 2000). The apparatus was constructed on a Nikon inverted microscope (Diaphot, Japan) with the glass post microtool attached to the lever arm of an electromagnetic length control motor (Colomo et al. 1994) used for rapid length changes of the preparation for measurement of kTR (see below). Activation rate (kACT) and kTR were estimated from mono-exponential fits as previously described (Tesi et al. 2000). Relaxation rate for the slow phase (kREL,slow) was calculated from the slope of the regression line fitted to the tension trace normalized to the entire amplitude of the tension relaxation transient. The relaxation rate for the fast phase (kREL,fast) was measured from a single exponential decay fitted to the data. For fitting, transition from the slow to rapid phase was determined subjectively from individual traces. The duration of the slow phase was measured from tension traces from the onset of solution change at the myofibril to the intercept of the regression line with the fitted exponential. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare between myofibril groups after TnC exchange and when differences were significant, Student's unpaired t tests were used with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. All values reported in Table 3 for myofibril tension and kinetics are means ±s.e.m.

Table 3.

Tension generation and relaxation parameters for rabbit psoas myofibrils exchanged with sTnC mutants at 15°C

| Myofibril sTnC batch | Tension generation | Relaxation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmax (mN mm−2) | kACT (s−1) | kTR (s−1) | Slow phase | Fast phase kREL (s−1) | ||

| Duration (ms) | kREL (s−1) | |||||

| Sham-treated | 340 ± 22 (9) | 8.48 ± 0.62 (9) | 8.80 ± 0.61 (9) | 75 ± 7 (9) | 1.72 ± 0.25 (8) | 38.1 ± 6.0 (9 |

| WT sTnC | 330 ± 43 (11) | 8.17 ± 0.40 (11) | 8.23 ± 0.49 (11) | 76 ± 5 (11) | 1.43 ± 0.14 (11) | 44.2 ± 5.2 (11) |

| M80Q sTnCF27W | 331 ± 36 (13) | 8.06 ± 0.37 (13) | 8.36 ± 0.45 (13) | 102 ± 8 (13)#† | 1.53 ± 0.22 (13) | 29.1 ± 2.9 (12)† |

| I60Q sTnCF27W | 176 ± 16 (13)*° | 3.25 ± 0.32 (13)*° | 3.32 ± 0.33 (13)*° | 42 ± 3 (13)*° | 1.53 ± 0.21 (13) | 49.6 ± 2.9 (13) |

Number in parentheses is number of myofibrils. Fmax, maximum isometric tension; kACT, rate constant of tension rise following step-wise pCa decrease (8.0–3.5); kTR, rate constant of tension redevelopment following release-restretch of myofibril; kREL, rate constant of tension relaxation for slow and fast phases following step-wise pCa increase (3.5–8.0). *P < 0.01 versus sham-treated; °P < 0.01 versus WT sTnC; #P < 0.05 versus sham-treated; †P < 0.05 versus WT sTnC.

Rate of tension redevelopment (kTR)

The rate of tension redevelopment (kTR) was determined from tension traces following a rapid release–restretch transient as previously described for fibres (Chase et al. 1994; Regnier et al. 1996, 1998) and for myofibrils (Tesi et al. 2000). Briefly, once steady-state tension was achieved, the fibre was shortened by 0.15 Lo at a 10 Lo s−1 ramp, held at this position for 20 ms, then followed by a rapid (300 μs) under-damped restretch to 1.05 Lo (held for 1 ms) and finally released back to Lo. Myofibrils were shortened by 0.30 Lo with a step length change, held at this position for 35 ms, then rapidly restretched to Lo. Tension in both fibres and myofibrils was reduced to zero during shortening, transiently spiked with rapid restretch, then redeveloped to steady-state levels characterized by an apparent rate constant. The apparent rate constant, kTR, was estimated for myofibrils from mono-exponential fits (see above) and was calculated for fibres from the half-time of tension recovery (t1/2) after restretch as

| (2) |

Corresponding tension values at a given pCa are normalized to the maximum for each condition (Figs 1A and B, and 4) or to the maximum just prior to extraction of sTnC (Figs 1C, 3 and 5).

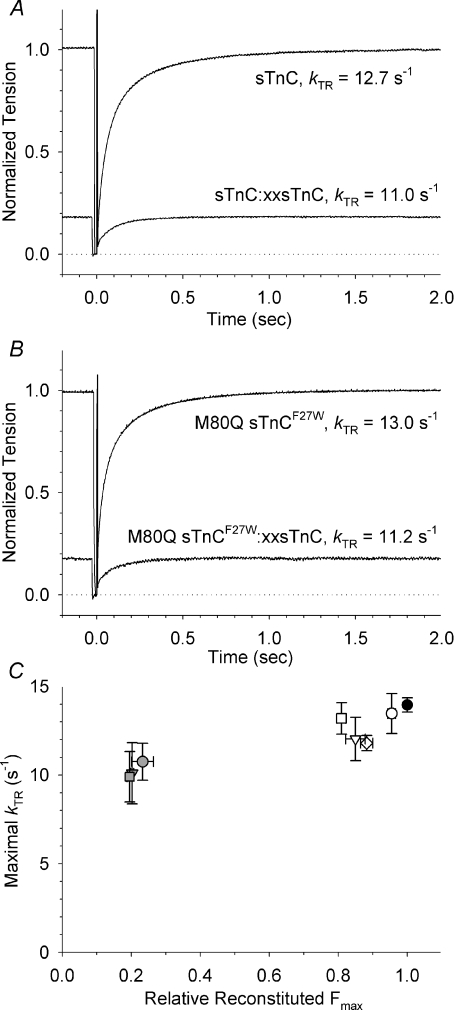

Figure 1. Rate of tension redevelopment (kTR) in single permeabilized rabbit psoas fibres reconstituted with purified sTnC, recombinant mutant M80Q sTnCF27W, or mixtures of D28A, D64A sTnC (xxsTnC) with either sTnC or M80Q sTnCF27W to ∼0.2 Fmax at saturating Ca2+ (pCa 4.5; A and B) and maximal kTRversus relative reconstituted Fmax for all thin filament reconstitution conditions (C).

A and B, example tension traces comparing kTR in different fibres after extraction of native sTnC and reconstitution with 100% purified sTnC, 100% M80Q sTnCF27W, or mixtures of sTnC and xxsTnC or M80Q sTnCF27W and xxsTnC to recover ∼0.2 Fmax. Reconstituted Fmax was 1.00 for 100% sTnC, 0.82 for 100% M80Q sTnCF27W, 0.18 for sTnC: xxsTnC, and 0.18 for M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC. Traces for 100% sTnC and 100% M80Q sTnCF27W were normalized relative to their own maximal tension at maximal Ca2+ (pCa 4.5). Tension traces of maximal kTR with xxsTnC mixtures are shown at their reconstituted tension levels, ∼0.2 Fmax. Values of kTR are given in the figure. Dotted line indicates zero tension. Pre-extracted Fmax was 435 mN mm−2 for 100% sTnC, 257 mN mm−2 for 100% M80Q sTnCF27W, 242 mN mm−2 for sTnC: xxsTnC, and 365 mN mm−2 for M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC. C, relationship between maximal kTR (pCa 4.5) and reconstituted Fmax for fibres reconstituted with sTnC (○), M80Q sTnC (▿), sTnCF27W (◊), or M80Q sTnCF27W (□) and fibres reconstituted with xxsTnC in mixtures with sTnC (grey circles), M80Q sTnC (grey arrowheads) or M80Q sTnCF27W (grey squares) to ∼0.2 Fmax. Reconstituted Fmax for each condition was normalized relative to pre-extracted Fmax (•). Maximal kTR values and number of fibres for each group are given in Table 2. Reconstituted Fmax was 0.96 ± 0.01 for sTnC, 0.88 ± 0.02 for sTnCF27W, 0.85 ± 0.03 for M80Q sTnC, 0.81 ± 0.01 for M80Q sTnCF27W, 0.23 ± 0.03 for sTnC: xxsTnC, 0.20 ± 0.01 for M80Q sTnC, and 0.20 ± 0.01 for M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC as previously reported (Kreutziger et al. 2007). Maximal kTR values are not different between all groups by ANOVA. Some error bars are smaller than symbols.

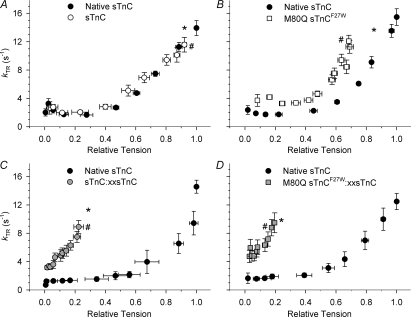

Figure 4. Example tension traces and Ca2+ sensitivity of kTR for fibres with 100% sTnC or 100% M80Q sTnCF27W (A–D) or reduced near-neighbour RU interactions (E and F).

A, example tension traces at pCa 6.0 for fibres reconstituted with 100% sTnC or 100% M80Q sTnCF27W. Traces are normalized to their own Fmax. B, example tension traces at different pCa values but similar tension levels at ∼0.88 Fmax and ∼0.35 Fmax. Reconstituted Fmax was 0.97 for 100% sTnC and 0.82 for 100% M80Q sTnCF27W. The trace for M80Q sTnCF27W at pCa 6.0 is the same for panels A and B. In A and B, dotted line indicates zero tension and pre-extracted Fmax was 308 mN mm−2 for 100% sTnC and 257 mN mm−2 for 100% M80Q sTnCF27W. C–F, kTR–pCa relationships are shown for fibres prior to sTnC extraction (•) and following reconstitution with sTnC (○; C), M80Q sTnCF27W (□; D), sTnC: xxsTnC (grey circles; E), and M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC (grey squares; F). Reconstituted Fmax values are given in the legend to Fig. 1C. Some error bars are smaller than symbols. *Maximal values just after reconstitution (in a back-to-back comparison with pre-exchange Fmax and kTR,max). #Maximal values at the end of the pCa curve (demonstrating extent of fibre run-down).

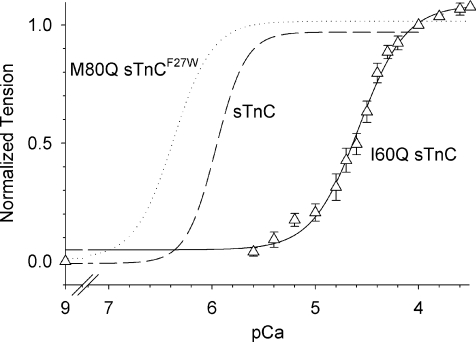

Figure 3. Tension–pCa relationship in skeletal fibres reconstituted with I60Q sTnC.

Extraction of native sTnC was followed by reconstitution with I60Q sTnC (▵), yielding 0.59 Fmax at saturating Ca2+ (pCa 3.5; n = 4 fibres). Normalized tension–pCa shows curve fits to the Hill equation for purified sTnC and M80Q sTnCF27W as previously published (dashed and dotted curves, respectively; Kreutziger et al. 2007). Fibres with I60Q sTnC had a reduced Ca2+ sensitivity (continuous curve; pCa50= 4.55 ± 0.07) and slope (nH= 1.7 ± 0.2) versus purified sTnC (pCa50= 5.96 ± 0.03; nH= 3.2 ± 0.4; Kreutziger et al. 2007).

Figure 5. Relationship between kTR and relative steady-state tension as pCa was varied.

kTR values at each pCa in Fig. 4 were re-plotted versus the steady-state isometric tension achieved at that pCa (i.e. data were binned by pCa). Tension was normalized relative to the pre-extracted Fmax for each group. Reconstitution conditions for each panel and the symbols are the same as in Fig. 4. Some error bars are smaller than symbols. *Maximal values just after reconstitution. #Maximal values at the end of the pCa curve.

Troponin C replacement

Replacement of native sTnC in fibres was accomplished by extracting native sTnC, followed by reconstituting troponin complexes with recombinant or purified sTnC. sTnC extraction solution contained (mm): Mops 10, EDTA 5 and trifluoperazine (TFP) 0.5 at pH 6.6 at 15°C. Selective sTnC extraction was completed to 1.3 ± 0.1%Fmax (n = 50) with repeated incubations in extraction solution (30 s) and pCa 9.0 solution (10 s) as previously described (Regnier et al. 1999; Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2005). Reconstitution with 1 mg ml−1 of total sTnC protein in pCa 9.0 solution was completed with two incubations of 2 min and 1 min. If Fmax did not increase after the second incubation, reconstitution was considered complete. Reported reconstituted Fmax values (Fig. 1C) are from back-to-back measurements in pCa 4.5 comparing just prior to extraction and immediately following reconstitution. To ensure that Tn complexes were complete after reconstitution with I60Q sTnC, an additional 1 min incubation in purified sTnC was performed and tension measured. No increase in Fmax at pCa 3.5 (to ensure saturation of tension; Fig. 3) indicated that all Tn complexes were complete and the observed reduction in Fmax was in fact due to the sTnC properties and not incomplete reconstitution. ANOVA and Student's t tests were used to compare reconstituted Fmax between fibre groups. Replacement of native sTnC in myofibrils was accomplished by passive sTnC exchange. Exchange of sTnC in myofibrils was carried out at 4°C overnight by incubating homogenized myofibrils in relaxing solution added with 0.05 mg ml−1 recombinant sTnC. Batches of myofibrils prepared each time included untreated myofibrils (as a control for quality of preparation), sham-treated myofibrils (as a control for the exchange protocol; ‘Sham-treated’ in Table 3), and sTnC-treated myofibrils (test groups) including WT sTnC (as a control for sTnC mutant-exchanged myofibrils), M80Q sTnCF27W, I60Q sTnCF27W and xxsTnC (which does not bind Ca2+ at either site I or site II, as a control for extent of exchange in myofibrils). Following this exchange protocol no myofibrils developed any significant tension in relaxing solution at 2.6 μm SL and no significant difference was found in Fmax and kinetic parameters between untreated, sham-treated and WT sTnC-exchanged myofibrils. This indicates that the sTnC-exchange protocol per se is not affecting myofibril mechanics, kinetics and regulation. Myofibrils exchanged with xxsTnC resulted in ∼5%Fmax values compared with sham-treated or WT sTnC-exchanged myofibrils, suggesting that > 90% of sTnC was exchanged. Qualitatively similar results were obtained by an extraction–reconstitution protocol previously described (Piroddi et al. 2003). In the current study we chose to use the exchange protocol because tension levels were better maintained compared with controls.

Ca2+ dissociation rate from sTn

Ca2+ dissociation rate (koff) from whole sTn (containing I60Q sTnC or I60Q sTnCF27W and native purified sTnI and sTnT) was measured at 15.0°C using an Applied Photophysics Ltd (Leatherhead, UK) model SX-18MV stopped-flow instrument as previously described (Tikunova et al. 2002; Gomes et al. 2004; Kreutziger et al. 2007). Briefly, Ca2+ was removed from sTn using the fluorescing Ca2+ chelator Quin-2 (Calbiochem) with excitation at 330 nm. Increases in Quin-2 fluorescence were monitored through a 510 nm broad bandpass interference filter (Oriel) and two to four raw data traces averaged before being fitted with a single exponential curve. Reported koff values represent the mean ±s.e.m. of the rate reported from six to eight average traces for each sTn with variance less than 3.3 × 10−3 (Table 1). Whole sTn (6 μm) with no additional Ca2+ was rapidly mixed with 150 μm Quin-2. The buffer used was (mm): Mops 10, KCl 150, MgCl2 1, DTT 1, pH 7.0 at 15°C as previously described (Kreutziger et al. 2007). Newly reported koff for I60Q sTnC-sTn and I60Q sTnCF27W-sTn was measured at the same time and under the same conditions as measurements for M80Q-containing mutants, first reported in Kreutziger et al. (2007), allowing for direct comparisons between koff values between all of these whole sTn complexes. Values for koff from whole sTn complexes are repeated in Table 1 taken from Kreutziger et al. (2007) for ease of comparison for WT sTnC-sTn, M80Q sTnC-sTn, sTnCF27W-sTn and M80Q sTnCF27W-sTn.

Table 1.

Ca2+ dissociation rate (koff) measured in whole sTn with sTnC mutants at 15°C

| sTnC in sTn (n) | koff (s−1) |

|---|---|

| WT sTnC (6) | 5.57 ± 0.04* |

| sTnCF27W (7) | 4.57 ± 0.02* |

| M80Q sTnC (7) | 3.25 ± 0.01* |

| M80Q sTnCF27W (7) | 2.16 ± 0.02* |

| I60Q sTnC (8) | 79.69 ± 2.33 |

| I60Q sTnCF27W (8) | 62.01 ± 1.06 |

Previously reported in Kreutziger et al. (2007) and repeated here for comparison. n, number of traces (see Methods).

Results

Maximal rate of tension redevelopment in skeletal fibres

To determine how increased Ca2+-binding affinity of sTnC influences contractile kinetics, we measured the rate of tension redevelopment (kTR) following a release–restretch length transient in single skinned rabbit psoas fibres. Example tension traces at saturating Ca2+ (pCa 4.5) are shown in Fig. 1 and are used to determine the maximal kTR (kTR,max). The top trace in Fig. 1A is from a fibre reconstituted with 100% sTnC from which kTR was calculated to be 12.7 s−1. To study how an increased affinity of sTnC altered kTR, fibres were reconstituted with 100% M80Q sTnCF27W This sTnC mutant has a 61% slower Ca2+ dissociation rate (koff) and an increased steady-state Ca2+ affinity (Kd) as we previously reported (Table 1 and Kreutziger et al. 2007). kTR,max following reconstitution was 13.0 s−1 (Fig. 1B, top trace), suggesting no difference compared with fibres containing 100% sTnC.

To reduce near-neighbour regulatory unit (RU) interactions in the thin filament, which are a major source of cooperative activation in skeletal muscle (Regnier et al. 2002; Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2005; Kreutziger et al. 2007), fibres were reconstituted with mixtures of sTnC and D28A, D64A sTnC (xxsTnC; which does not bind Ca2+ in N-terminal sites I and II). A mixture ratio of ∼20% sTnC and ∼80% xxsTnC (denoted 20: 80 sTnC: xxsTnC) was used to achieve ∼0.2 of the pre-extracted maximal Ca2+-activated tension (Fmax). An example tension trace from a fibre reconstituted to 0.18 Fmax shown in Fig. 1A (bottom trace) resulted in a kTR,max of 11.0 s−1. This agrees with our previous report suggesting that near-neighbour RU interactions have little or no effect on kTR,max (Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007). Reconstitution of fibres with M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC required using a ∼40: 60 ratio mixture to achieve 0.2 Fmax (see Kreutziger et al. 2007) for explanation of mixture content versus reconstituted Fmax). An example tension trace for a fibre reconstituted to 0.18 Fmax resulted in a kTR,max of 11.2 s−1 (Fig. 1B, bottom trace). This suggests that increased Ca2+-binding affinity of sTnC does not influence kTR,max even with severely reduced near-neighbour RU interactions.

kTR,max data for all fibre groups are shown in Fig. 1C as a function of reconstituted Fmax to examine how kinetics are related to total tension generating capacity in skeletal fibres. In addition to 100% sTnC and 100% M80Q sTnCF27W, some fibres were reconstituted with two other mutants, sTnCF27W and M80Q sTnC. koff values for sTnC mutants in whole sTn complex decreased in the order of WT sTnC > sTnCF27W > M80Q sTnC > M80Q sTnCF27W, as previously reported (Table 1 and Kreutziger et al. 2007). In spite of the differences in koff, kTR,max did not differ between fibre groups (Table 2). kTR,max was also unaffected for fibres reconstituted with mixtures of xxsTnC and native or mutant sTnC to obtain ∼0.2 Fmax (Fig. 1C). All fibre groups showed slight reductions in kTR,max by paired t test versus pre-extracted kTR,max, possibly due to fibre run-down over the course of the experiment. Statistical analysis of the reconstituted kTR,max values with an ANOVA test showed no difference between any of the reconstituted values, including those with reduced near-neighbour RU interactions. The combined data suggest that increasing Ca2+ affinity of sTnC does not increase kTR,max in skeletal fibres and that kTR,max in skeletal muscle is not dependent on Fmax or thin filament near-neighbour RU interactions, as previously suggested (Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007).

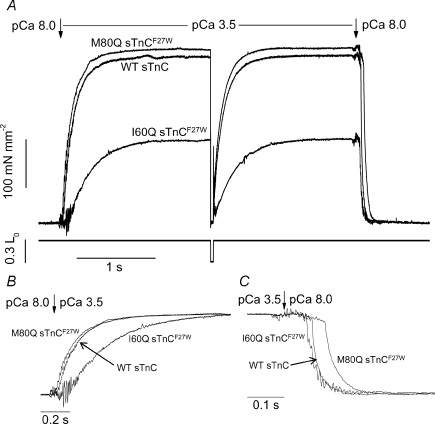

Maximal activation and relaxation kinetics in skeletal myofibrils

Single or small bundles of rabbit psoas myofibrils were used to measure tension activation with a rapid increase in Ca2+ and then relaxation with a rapid decrease in Ca2+ for the same preparation. kTR can also be measured during this activation–relaxation cycle, which enables comparison of activation rate (kACT) and kTR. Measurements were made at maximal Ca2+ (pCa 3.5) to determine if maximal kACT could be increased by a sTnC mutant with greater Ca2+ affinity even though kTR,max is unchanged. Example traces of maximal activation–relaxation cycles are shown in Fig. 2A for myofibrils exchanged with wild-type (WT) sTnC, M80Q sTnCF27W and I60Q sTnCF27W. A rapid solution change from pCa 8 to pCa 3.5 (first arrow) activated the myofibrils, causing a rise in tension that is characterized by kACT (shown normalized to Fmax for each trace in Fig. 2B). Once steady-state tension was reached, a length transient was used to measure kTR (length trace is shown below tension trace in Fig. 2A). Bi-phasic relaxation occurred with rapid solution change from pCa 3.5 to pCa 8 (second arrow in Fig. 2A) and is shown with greater temporal resolution and normalized to Fmax for each trace in Fig. 2C. Relaxation is characterized by a slow phase rate (kREL,slow) and duration and by a fast phase rate (kREL,fast; see Methods for parameter estimation). Sham-treated myofibrils produced an Fmax of 340 ± 22 mN mm−2 and were not different from untreated myofibrils (data not shown). Fmax was not different for WT sTnC-exchanged myofibrils (Table 3). To determine the extent of sTnC exchange, a subgroup of myofibrils was exchanged with 100% xxsTnC for each experimental batch. These myofibrils produced 17 ± 9 mN mm−2 tension (n = 10) or ∼5% of sham-treated or WT Fmax, suggesting that greater than 90% of native sTnC was exchanged for exogenous sTnC. Sham-treated and WT sTnC-exchanged myofibrils did not differ for any kinetic parameters (Table 3). Parameters describing bi-phasic relaxation (kREL,slow, duration and kREL,fast; reviewed in Poggesi et al. 2005) for sham-treated and WT sTnC-exchanged myofibrils were similar to previously reported values (Tesi et al. 2002; de Tombe et al. 2007). These control experiments suggest the exchange procedure did not alter myofibril mechanics. As the M80Q sTnCF27W mutant had the most dramatic reduction of koff, we focused on this sTnC mutant to examine how decreased Ca2+ dissociation from sTnC affected tension kinetics. For M80Q sTnCF27W-exchanged myofibrils, there was no change in kACT or kTRversus WT sTnC (or sham-treated myofibrils) at maximal Ca2+, similar to comparisons for Fmax (Table 3; Fig. 2B). These data suggest that in the presence of saturating Ca2+, a higher affinity of sTnC for Ca2+ (with M80Q sTnCF27W) does not alter the relationship between kACT and kTR. During relaxation with M80Q sTnCF27W, there was no change in kREL,slow and a small decrease in kREL,fast (P < 0.05 versus WT sTnC; although t test versus sham-treated indicates no significant difference). Surprisingly, the duration of the slow phase of relaxation was increased by 34% for M80Q sTnCF27W (P < 0.05; Fig. 2C; Table 3). These data suggest that increasing Ca2+ affinity of sTnC (via decreased koff) prolongs thin filament activation upon rapid removal of Ca2+, thus delaying the onset of the fast phase of relaxation, without altering the rate at which isometric relaxation occurs. To further examine how Ca2+ affinity of sTnC affects tension development and relaxation kinetics in myofibrils, we used a mutant sTnC with an increased Ca2+-koff. I60Q sTnC and I60Q sTnCF27W had koff values that were 14-fold and 11-fold faster, respectively, in whole sTn complex at 15°C versus WT sTn (Table 1). Characterization of I60Q sTnC in single skinned psoas fibres (Fig. 3) showed reduced Fmax (by ∼40%), pCa50 (by 1.41 pCa units) and kTR,max (by ∼70%; Tanner, 2007). Due to the severe loss of Ca2+ sensitivity with I60Q sTnC, pCa 3.5 was used to saturate the thin filament and Ca2+-activated tension, which is saturated and well-fitted by the sigmoidal Hill equation (Fig. 3). These changes in tension–pCa were similar to previous experiments using other TnCs with increased koff (Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007), and should be similar for I60Q sTnCF27W (not characterized in fibres) because of the comparable increase in koff. In skeletal myofibrils, our goal was to determine if faster koff differentially affected activation (kACT) and relaxation kinetics. Exchanging I60Q sTnCF27W into myofibrils resulted in 0.53 Fmaxversus WT sTnC myofibrils (Table 3). With an increased koff, I61Q sTnCF27W slowed both kACT and kTR by ∼60% at maximal Ca2+, in contrast to when koff was reduced with M80Q sTnCF27W (Table 3). Examining relaxation showed that the duration of the slow phase of relaxation was reduced by 45% with I60Q sTnCF27W. However, increasing koff with I60Q sTnCF27W had no effect on kREL,slow and kREL,fast, similar to results when koff was reduced with M80Q sTnCF27W. Combined, the data indicate that koff has little influence on relaxation rates but does influence the duration of the isometric slow phase. In addition, decreases in koff do not influence tension development rates, but large increases in koff can dramatically decrease both steady-state tension and the rate of tension development.

Figure 2. Activation, kTR and relaxation in single rabbit psoas myofibrils upon rapid change in pCa for a WT sTnC-exchanged myofibril, a M80Q sTnCF27W-exchanged myofibril, and a I60Q sTnCF27W-exchanged myofibril.

A, example tension traces of activation–relaxation cycles in single or small bundles of myofibrils show tension through time. Activation (characterized by kACT) upon rapid increase in Ca2+ from pCa 8 to pCa 3.5 (first arrow), kTR with a release–restretch length transient, and relaxation with rapid decrease in Ca2+ (second arrow) are shown. Changes in myofibril length are seen in bottom trace for kTR measurement. B, expanded time scale with tension normalized to maximum for each condition during activation (pCa 8.0 to 3.5; arrow) shows a reduced kACT for I60Q sTnCF27W. C, expanded time scale with normalized tension traces during relaxation (pCa 3.5 to pCa 8.0; arrow) shows a prolongation of slow phase duration with M80Q sTnCF27W and a reduction of slow phase duration with I60Q sTnCF27W. Myofibril diameter, Lo and SL were 1.91, 42 and 2.57 μm, respectively (WT sTnC); 2.00, 49.4 and 2.63 μm (M80Q sTnCF27W); 1.72, 29.8 and 2.55 μm (I60Q sTnCF27W). Tension and kinetic parameters are reported in Table 3.

Ca2+ sensitivity of the rate of tension redevelopment in skeletal fibres

At submaximal levels of Ca2+ activation, altering the Ca2+ affinity of sTnC had striking effects on steady-state tension and kTR. As with myofibril studies, we focused on the M80Q sTnCF27W mutant because it had the most dramatic reduction of koff. Reconstitution of fibres with 100% M80Q sTnCF27W resulted in higher tension and faster kTR at most submaximal levels of Ca2+. For the example tension traces in Fig. 4A, steady-state tension was greater by 2/3 and kTR was more than doubled for the M80Q sTnCF27W reconstituted fibre compared with 100% sTnC at pCa 6.0 (P < 0.01 for unpaired t test). The elevated kTR with M80Q sTnCF27W was not completely explained by the higher tension level, as demonstrated by tension-matched traces in Fig. 4B. At a lower tension level (0.35 Fmax) M80Q sTnCF27W had an elevated kTR at 3.8 s−1versus 2.2 s−1 with sTnC. However, this effect was eliminated at higher tensions, as shown by the upper two traces at 0.88 Fmax in Fig. 4B. These data suggest that the decreased Ca2+-koff of M80Q sTnCF27W may increase kTR at lower, but not higher, levels of submaximal thin filament activation.

The kTR data as Ca2+ was varied for all fibres reconstituted with 100% sTnC or 100% M80Q sTnCF27W are summarized in Fig. 4C and D, respectively. Plots of kTR–pCa are shown in each panel for pre-extracted (filled circles) and reconstituted fibres. Data of average values were well-fitted by the Hill equation (eqn (1); fits not shown) and pCa50 values are reported in Table 2. In control experiments, the full range of Ca2+ dependence of kTR was maintained following reconstitution with 100% sTnC and values were similar at all pCa levels (Fig. 4C). The rise in steady-state tension with increasing Ca2+ preceded that of kTR (Kreutziger et al. 2007). Fibres reconstituted with 100% sTnC showed no change in Ca2+ sensitivity (pCa50) of kTRversus pre-extracted value (Table 2), demonstrating the sTnC extraction–reconstitution protocol did not alter the kTR–pCa relationship. kTR was fairly constant at low Ca2+ (≥ pCa 6.0) and the rise in kTR lagged behind that of tension and did not increase above ∼2 s−1 until tension was ≥ 0.5 Fmax. Overall, for all thin filament reconstitution conditions (1) the kTR–pCa data maintain a large range of kTR values from low Ca2+ to maximum Ca2+ (i.e. strong Ca2+ dependence of kTR; Fig. 4C–F), and (2) the change in Ca2+ sensitivity of kTR (pCa50 of kTR) is similar in direction and magnitude to the change in pCa50 of tension (Kreutziger et al. 2007). For fibres reconstituted with 100% M80Q sTnCF27W, Ca2+ dependence of kTR (defined as the range of kTR values from low to high Ca2+) was reduced due to a small but significant elevation of low-Ca2+kTR values (P < 0.05 by paired t test at each pCa > 6.1; Fig. 4D). pCa50 of kTR increased with M80Q sTnCF27W by ∼0.2, shifting kTR data to the left (Fig. 4D; Table 2). As noted above, kTR,max was reduced for all reconstitution conditions versus pre-extracted kTR,max (by paired t test), but there was no difference in kTR,max between reconstitution groups by ANOVA. These data demonstrate that M80Q sTnCF27W has a greater effect on kTR at lower Ca2+ levels.

Reduction of near-neighbour RU interactions in the thin filament using sTnC: xxsTnC mixtures allowed for examination of how these cooperative interactions alter kTR–pCa. Further, mixtures of xxsTnC and the mutant M80Q sTnCF27W (with a decreased koff) were used to examine how Ca2+ binding properties of sTnC are coupled to near-neighbour RU interactions for setting kTR. Reconstitution to 0.2 Fmax with sTnC: xxsTnC slightly reduced the Ca2+ dependence of kTR via decreased kTR,max (P < 0.05 by paired t test; not different from reconstitution groups by ANOVA) and via slightly elevated kTR at low Ca2+ (not significant for pCa 6.2–5.8), similar to previous reports (Fitzsimons et al. 2001; Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007). pCa50 of kTR was reduced by ∼0.4 with sTnC: xxsTnC, which is probably due to both a rightward shift and loss of slope of the kTR–pCa relationship (Fig. 4E; Table 2). Reconstitution to 0.2 Fmax with M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC (to reduce near-neighbour RU interactions and increase Ca2+ affinity of sTnC) also reduced Ca2+ dependence of kTR via decreased kTR,max (P < 0.05 by paired t test; not different from reconstitution groups by ANOVA) and via elevated kTR at low Ca2+ (P < 0.01 for pCa 6.4–6.0; P < 0.02 for pCa 5.9). pCa50 of kTR was reduced by ∼0.1 in fibres reconstituted with M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC mixtures (Fig. 4F; Table 2), which was less than the loss of Ca2+ sensitivity of kTR in fibres with sTnC: xxsTnC. Interestingly, the change in pCa50 of kTR (ΔpCa50) between M80Q sTnCF27W and sTnC was 0.2 and between mixtures M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC and sTnC: xxsTnC was 0.3. These ΔpCa50 values suggest that increased Ca2+ affinity of sTnC can increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of kTR in both the presence and absence of near-neighbour RU interactions.

To examine how Ca2+-dependent increases in kTR depended on the number of strong-binding crossbridges available for tension generation and thin filament activation, the data of Fig. 4C–F were replotted as kTRversus steady-state tension where data were binned by pCa value (Fig. 5). This relationship exhibits changes in kTR at similar levels of steady-state tension under different sTnC-reconstitution conditions and independent of Ca2+ level. Pre-extracted data (filled circles) followed a concave curve because steady-state tension increased prior to the increase in kTR with increasing Ca2+. Fibres reconstituted with sTnC exhibited the same curvilinear relationship for kTR–tension (Fig. 5A), verifying that the protocol for incorporating sTnC did not alter the relationship between tension and kTR in fibres. Reconstitution with M80Q sTnCF27W increased kTR at all values of relative tension (open squares, Fig. 5B). As reconstituted Fmax was reduced with M80Q sTnCF27W, it is not clear whether or not the apparent elevation of kTR at higher, submaximal relative tension levels is due to the koff of M80Q sTnCF27W or some other mechanism (like run-down) that reduced Fmax. At tension levels < 50%, kTR was elevated with M80Q sTnCF27W, suggesting that decreased koff allowed for faster kTR at low levels of crossbridge binding and of thin filament activation. For fibres reconstituted with sTnC: xxsTnC, while reduced near-neighbour RU interactions resulted in much lower Fmax, kTR was somewhat elevated at all relative tension levels (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that spread of activation between near-neighbour RUs may limit kTR at low Ca2+ and low tension levels but probably have little effect on kTR at high Ca2+. M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC reconstituted fibres showed a slightly greater increase in low-tension kTR values (not significant; Fig. 5D) than either 100% M80Q sTnCF27W (Fig. 5B) or sTnC: xxsTnC (Fig. 5C). Therefore, Ca2+ binding kinetics of sTnC may influence kTR at low levels of thin filament activation independent of near-neighbour RU interactions, and certainly both near-neighbour RU interactions and koff of sTnC contribute to kTR at low Ca2+ and low tension.

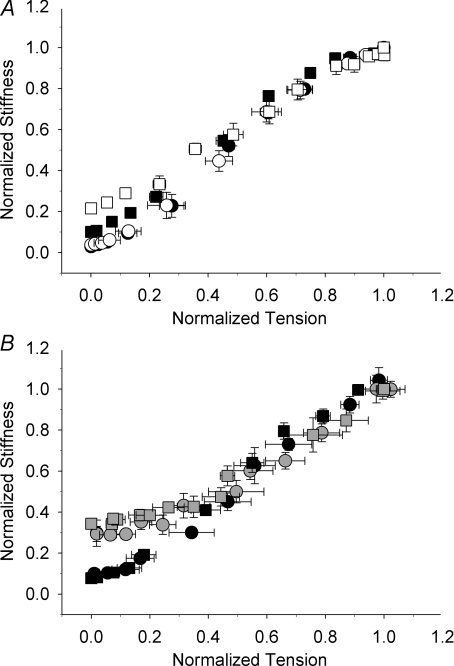

To better understand the mechanism by which kTR was increased at low tension levels (< 50%Fmax) for these variations to the thin filament activation properties, we examined fibre stiffness, which includes components of both crossbridge and filament stiffness. High-frequency sinusoidal stiffness was not altered in fibres reconstituted with 100% sTnC (Fig. 6A, white circles) versus pre-extracted control measurements (black circles), suggesting that the extraction–reconstitution protocol did not alter the stiffness–tension relationship. In fibres containing M80Q sTnCF27W, stiffness increased at Ca2+ activated tension levels < 0.2 Fmax (P < 0.05) for tension-matched kTR at < 0.2 Fmax (Fig. 6A, white squares) versus pre-extracted native sTnC (black squares). These data suggest that altered Ca2+-binding kinetics of sTnC altered crossbridge and/or filament stiffness. Reduction of near-neighbour RU interactions with xxsTnC mixtures also elevated the low-tension versus stiffness relationship (P < 0.05) at < 0.3 Fmax for sTnC: xxsTnC (grey cirles) or M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC (grey squares) for tension-matched comparisons with pre-extracted native values (black symbols; Fig. 6B). Interestingly, this elevation of stiffness at low tension due to reduced near-neighbour RU interactions was independent of whether mixtures contained sTnC or M80Q sTnCF27W. These observed effects of koff and near-neighbour RU interactions on fibre stiffness could contribute to the elevation of kTR at low levels of Ca2+ activation. All together, the data suggest that sTnC's Ca2+-binding properties in individual RUs and interactions between neighbouring RUs can both influence kTR at low Ca2+ or low tension levels.

Figure 6. Relationship between normalized stiffness and tension as pCa was varied in the presence (A) and absence (B) of near-neighbour RU interactions.

High-frequency sinusoidal stiffness was measured in a subset of experiments prior to extraction for each group (black symbols) and after reconstitution with 100% sTnC (white circles; n = 6 fibres; A), 100% M80Q sTnCF27W (white squares; n = 4 fibres; A), sTnC: xxsTnC (grey circles; n = 3 fibres; B), and M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC (grey squares; n = 4 fibres; B) and normalized to maximal stiffness for each condition.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to examine how altering the Ca2+ dissociation rate (koff) of sTnC influenced the kinetics of tension activation and relaxation as Ca2+ was varied and as near-neighbour regulatory unit (RU) interactions were reduced in skeletal muscle. Both single fibre and myofibril preparations were used because of their individual advantages. Single fibres offer the ability for multiple Ca2+ activations, but their size limits the ability to investigate activation and relaxation kinetics due to diffusion limitations. Myofibrils do not have these diffusion limitations because of their size, but the quality of mechanical measurements decays after a few activations. Our main findings are that decreasing koff of sTn does not change the maximal rates of tension development (measured as kACT, kTR) or relaxation (kREL,slow and kREL,fast), but increases kTR at low tension levels in the absence or presence of near-neighbour RU interactions. However, the duration of slow phase, isometric relaxation is prolonged. In contrast, increasing the koff of sTn reduces maximal tension development kinetics and shortens the duration of slow phase relaxation. Additionally, reduced near-neighbour RU interactions had no effect on maximal tension development kinetics but increased kTR and stiffness at low tension levels, and there was little or no effect on the kTR–tension relationship when koff was decreased (Fig. 5C and D). These results suggest that native sTn may be optimized to provide maximal activation kinetics and to modulate the rate of force development with small changes in intracellular Ca2+. This appears to be primarily a function of individual sTn complexes, with some modulation of rate by near-neighbour RU interactions at low Ca2+. Additionally, we have shown for the first time that increasing koff of sTn affects both activation and relaxation, while decreasing koff only affects relaxation. Below we discuss results with altered koff of sTnC in thin filaments with the full complement of functional regulatory units, followed by a discussion of reduced near-neighbour RU interactions.

Influence of koff on the maximal rate of tension development

We found that maximal kTR (kTR,max) was not altered by sTnC mutants having a decreased Ca2+ dissociation rate (koff) in fibres and myofibrils (Fig. 1C; Tables 2 and 3). This agrees with previous reports using calmidazolium or bepridil to decrease Ca2+–koff (Regnier et al. 1996; de Tombe et al. 2007) and suggests that at saturating Ca2+, kTR,max cannot be increased above that measured with native sTnC by altering the Ca2+-binding properties of sTnC. Since kTR,max is not limited by a lack of available Ca2+ or Ca2+-binding properties of sTnC, other processes following Ca2+ binding that lead to tropomyosin movement or the kinetics of crossbridge transitions must determine kTR,max (the latter explanation has been suggested previously (Brenner & Eisenberg, 1986; Brenner, 1988; Metzger & Moss, 1990)). However, kTR,max can be decreased with a sTnC mutant having an increased koff (I60Q sTnCF27W) in myofibrils (Table 3). This agrees with our previous reports using cTnC or a sTnC mutant with a single N-terminal Ca2+ binding site where koff is increased relative to native sTnC (Morris et al. 2001; Piroddi et al. 2003; Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007). The kTR data in myofibrils with I60Q sTnCF27W at saturating Ca2+ (Table 3) can be simulated using a four-state model described by Regnier et al. (1999), as was done by Moreno-Gonzalez et al. (2007). Although increases in koff alone were not sufficient to simulate reduced kTR,max and reduced Fmax, increases in both koff and crossbridge detachment rate (gapp) did simulate these results well. This suggests that thin filament regulatory proteins may alter crossbridge attachment/detachment kinetics.

How the activation process regulates the rate of tension development in skeletal muscle is not well understood. There is some question of whether kTR is a measure that accurately describes the temporal sequence of myosin–thin filament interactions that occur during the contractile activation process. Another measure of tension development kinetics, the rate of activation (kACT) in myofibrils, occurs with a rapid increase from low to high Ca2+ (Fig. 2) and takes into account the Ca2+ activation pathway of thin filament proteins. Our data in skeletal myofibrils showed that kACT did not differ from kTR at saturating Ca2+ for sTnC, M80Q sTnCF27W or I60Q sTnCF27W (Table 3). Thus, our data demonstrating that kACT is equal to kTR suggest that thin filament activation kinetics are not limiting to the rate of tension development in skeletal muscle at high levels of Ca2+ and low Pi for either native sTnC or M80Q sTnCF27W On the contrary, when koff of sTnC was increased (with I60Q sTnCF27W), both kACT and kTR decreased to a similar extent, suggesting that the Ca2+ binding dynamics of I60Q sTnCF27W had become limiting for both types of measurements. Perhaps the reduced activation rates were due to the severe compromise in Ca2+ binding (increased koff) that did not allow for maximal activation of the thin filament. Indeed, changes in koff affect Ca2+ affinity and the steady-state level of thin filament activation level. Experimental evidence suggests that Ca2+ binding and tropomyosin mobility during activation is in rapid equilibrium preceding tension generation (Robertson et al. 1981; Kress et al. 1986). Our data suggest this rapid activation process is maintained even when koff of sTnC is altered, so that kACT and kTR at high Ca2+ are determined by the Ca2+-binding equilibrium and resulting activation level of thin filaments.

Influence of koff on relaxation

To our knowledge, this is the first report suggesting that thin filament Ca2+ dissociation alters isometric relaxation from maximal Ca2+ activation. We found no change in the kinetics of relaxation (kREL,slow and kREL,fast; Table 3), but discovered that the duration of the slow, isometric phase of relaxation was modulated by altered Ca2+–koff of sTnC in skeletal myofibrils. This result was very intriguing, as little is known about the role of thin filament regulatory protein dynamics in tension relaxation. The finding that the rate of slow phase relaxation (kREL,slow; Table 3) was unchanged by sTnC mutants supports the existing hypothesis that kREL,slow is primarily determined by the crossbridge detachment rate at maximal Ca2+ (Poggesi et al. 2005). In addition, the finding that the rate of fast phase relaxation (kREL,fast) was not different between WT and mutant sTnCs suggests that the phenomenon of sarcomeric ‘give’ itself is not dependent on Ca2+ dissociation kinetics of sTnC and how they influence thin filament de-activation (Stehle et al. 2002; Tesi et al. 2002; Poggesi et al. 2005). Surprisingly, M80Q sTnCF27W (decreased koff) increased the duration of slow phase by 34%, while I60Q sTnCF27W (increased koff) decreased the duration of the slow phase by 45% (Table 3). These data suggest that while the kREL,slow is independent of the Ca2+ binding kinetics of troponin, the duration of the slow phase and thus the onset of sarcomeric ‘give’ (fast phase) can be influenced by thin filament de-activation via changes in Ca2+–koff. Indeed, the isometric phase of relaxation involves not only Ca2+ dissociating from TnC but a regressing population of cycling crossbridges (Gordon et al. 2000), providing a mechanism whereby altered koff of sTnC could affect isometric relaxation duration without altering the rate of tension decline.

Few studies have probed how changes to Ca2+ kinetics of sTnC affect relaxation. Lou et al. (2002) found that the slow phase rate of relaxation from partial Ca2+ activation at low (5 μm) Pi was decreased when native sTnC was replaced with chicken M82Q sTnC in skinned skeletal fibres. Our measurements showing no change in slow phase rate, but a prolonged duration were from fully Ca2+ activated myofibrils to complete relaxation. Recently published results in skeletal myofibrils using bepridil showed no change in slow phase duration (de Tombe et al. 2007), contrary to our current results where duration of the slow phase was increased with M80Q sTnCF27W. Bepridil is a Ca2+-sensitizing agent that has been characterized in cardiac TnC to bind in the N-terminal domain in the presence of Ca2+ and decreases koff of isolated cardiac TnC (Solaro et al. 1986; MacLachlan et al. 1990; Li et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2002). However, the effect of bepridil on koff has not been measured either in skeletal TnC or in whole troponin complex, where koff is greatly slowed from values obtained with isolated TnC. Since M80Q sTnCF27W also has a decreased Ca2+–koff, we may have expected similar results to the bepridil experiments. The difference in how bepridil and M80Q sTnCF27W affected slow phase duration may have arisen from differences in the specificity of each of these Ca2+ sensitizers. It has been reported that bepridil binds to cardiac TnC in the presence of Ca2+ but not in its absence (MacLachlan et al. 1990; Li et al. 2004), thus its action during a step decrease in Ca2+ may be complex. The rapid reduction of Ca2+ to initiate relaxation in skeletal myofibrils could also initiate bepridil dissociation. Further study in this area is needed to examine how Ca2+ dissociation kinetics are related to the kinetics of thin filament de-activation and how these influence relaxation, particularly at submaximal Ca2+ levels. In summary, our current data suggest that koff of native sTnC may be optimal for allowing rapid activation and relatively rapid relaxation (i.e. a fairly short relaxation duration dominated by the fast phase).

Influence of koff on the rate of tension development (kTR) at low Ca2+

We found that incorporating I60Q sTnCF27W into myofibrils reduced Fmax by ∼50% and reduced kTR,max by ∼60% to 3.3 s−1, suggesting that compromising thin filament activation level can limit tension development kinetics. Indeed, kTR in fibres reconstituted with 100% sTnC at Ca2+ levels that produced ∼0.5 Fmax was 3–4 s−1 (Fig. 5A), which is much less than maximal kTR but similar to kTR with I60Q sTnCF27W in myofibrils. Other studies using the cardiac isoform of TnC (with increased koff) reconstituted into psoas fibres (Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007) or myofibrils (Piroddi et al. 2003) have reported reduced tension and kTR, similar to our data with I60Q sTnCF27W in myofibrils and I60Q sTnC in fibres. We recently reported that skeletal troponin containing cardiac TnC has an approximately 50% faster koff than troponin with a full complement of fast skeletal subunits (Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007). Together these data support the idea that the Ca2+ binding kinetics of sTnC can become limiting to kTR if koff is increased, even at saturating Ca2+.

Another line of evidence suggests that Ca2+ binding kinetics of sTnC can modulate kTR. kTR remained at a constant low value with increasing Ca2+ until tension was > 0.5 Fmax with native sTnC (Fig. 5A). However, when koff was decreased (with M80Q sTnCF27W), kTR was elevated at tension levels < 0.5 Fmax (Fig. 5B). In these experiments, we also measured high-frequency (1000 Hz) sinusoidal stiffness and steady-state force. Control measurements (Fig. 6A, circles) show that the extraction–reconstitution protocol did not affect stiffness–force. However, reconstitution with M80Q sTnCF27W showed that at tension < 0.2 Fmax, stiffness increased relative to force (Fig. 6A, white versus black squares). These data suggest that M80Q sTnCF27W altered filament and/or crossbridge contributions to stiffness, which agrees with Regnier et al. (1995) where we suggested an increase in stiffness relative to force was indicative of an increase in the population of bound crossbridges in pre-force states (i.e. weakly bound or strongly bound, low-force states). Further, at low levels of Ca2+ activation, a greater portion of the length change for measuring stiffness is transferred to the crossbridges versus at high Ca2+ activation (Martyn et al. 2002), suggesting that changes in crossbridge distributions could influence the stiffness–force relationship. In particular, the sinusoidal stiffness measurements made with M80Q sTnCF27W may be detecting increased weak and/or strong pre-force crossbridge binding, thus increasing stiffness relative to force at low Ca2+ (Fig. 6A). Therefore, the mechanism of increased kTR at low tension could involve increased crossbridges in pre-tension states (weakly or strongly bound), as kTR is an apparent rate of tension generation. This suggests that in native skeletal muscle, the fast koff of sTnC may limit weak and/or strong pre-force crossbridge binding, contributing to the slow kTR at tension < 0.5 Fmax.

Interestingly, either decreasing or increasing koff of sTnC increases kTR at low levels of Ca2+ activation, but this probably occurs by different mechanisms. How this might occur was discussed in a recent paper (Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007), but it bears some repetition here in the context of the current work. The time that any individual RU remains activated may be increased with decreased koff and decreased with increased koff. When koff is decreased, as for M80Q sTnCF27W, the effect at low Ca2+ is probably greater affinity (compared with WT sTnC) for TnI, and consequently a lower affinity of TnI for actin. This should result in maintaining tropomyosin in a position permissive to crossbridge binding. The possible means of an increased koff to increase kTR at low Ca2+ are less obvious. We previously reported a positive correlation between whole sTn koff and elevation of kTR at low Ca2+ when comparing native sTnC with cTnC or D28A sTnC, which both have increased koff (Fig. 5B in Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007). However, for these proteins, both maximal tension and kTR (pCa 4.0) were greatly reduced, in contrast to our results with M80Q sTnCF27W (Fig. 1C). This suggests a lower ability to activate the thin filament, even at high Ca2+. This could result from lower affinity of cTnC and D28A sTnC for TnI in rabbit psoas fibres at any given [Ca2+] and, consequently, greater affinity of TnI for actin. If so it could lead to an active role of Tn to re-stabilize tropomyosin in an inhibitory position and, thus, increase the crossbridge dissociation rate (Clemmens et al. 2005). While testing these ideas is beyond the scope of this study, our past and current data demonstrate the ability of altered koff to modulate crossbridge cycling kinetics at low levels of Ca2+ activation. In addition, the data from current and past studies strongly suggest kinetic coupling between thin filament and crossbridge cycling, especially at low levels of Ca2+ activation.

Influence of near-neighbour RU interactions on the rate of tension development (kTR)

A unique and important aspect of our study was to examine how the Ca2+-binding properties of sTnC act locally, within a regulatory unit (RU) of the thin filament, compared with the ensemble effects of troponin complexes along the length of thin filaments. This allowed us to separate the effects of decreased koff of sTnC from near-neighbour RU cooperative mechanisms on kTR. We and others have previously shown that near-neighbour RU interactions along the length of the thin filament are the dominant form of cooperative activation in skeletal fibres (as indicated by the slope, nH, of the tension–pCa relationship; Metzger & Moss, 1991; Regnier et al. 2002). As we previously found (Gillis et al. 2007; Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007), loss of near-neighbour RU interactions does not change kTR,max (Fig. 1), indicating that when the thin filament is saturated with Ca2+, near-neighbour RU interactions have little role in determining kTR. At the lowest levels of Ca2+, kTR is slightly elevated for sTnC: xxsTnC above pre-extracted values (Fig. 4E; not significant by paired t test), similar to results found by Fitzsimons et al. (2001) with partial extraction of sTnC. These data suggest that disrupting near-neighbour RU interactions may have released a limitation on the rate tension can redevelop. In addition, stiffness increased at tension < 0.3 Fmax for both sTnC: xxsTnC and M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC (Fig. 6B), where near-neighbour RU interactions were diminished. This suggests that filament stiffness may have increased with a combination of xxsTnC mixtures in the thin filament and low levels of activating Ca2+, as thin filament flexural rigidity increases (and presumably axial stiffness increases) at low [Ca2+] with regulated thin filaments (Isambert et al. 1995). Perhaps, under normal conditions, near-neighbour RU interactions increase filament compliance, which could limit kTR at low Ca2+ levels (with little effect at saturating Ca2+, as suggested by Razumova et al. 2000). However, our results show that the contribution of near-neighbour RU interactions to determining kTR is small and the Ca2+ dependence of kTR remains large in the absence of near-neighbour RU interactions (Fig. 4E). This remaining Ca2+ dependence may be a direct result of the level of activating Ca2+, since more Ca2+ is required to achieve a given relative tension level when near-neighbour RU interactions are reduced. This increased Ca2+ level may contribute to the elevation of kTR at the lower end of the kTR–tension relationship with diminished near-neighbour RU interactions (Fig. 5C), as previously suggested (Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007).

The finding that loss of near-neighbour RU interactions does not affect maximal kTR and only moderately elevates low-tension kTR demonstrates that much of the Ca2+ dependence of kTR resides within individual RUs. pCa50 of kTR was reduced by 0.13 (shifted to the right) for fibres reconstituted with M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC and by 0.43 for fibres reconstituted with sTnC: xxsTnC versus reconstitution with 100% sTnC. These data suggest that increasing the Ca2+ affinity of sTnC increases kTR at submaximal Ca2+ levels within RUs in the thin filament. At low Ca2+ levels for fibres reconstituted with M80Q sTnCF27W: xxsTnC, kTR may be elevated to a greater extent than in sTnC: xxsTnC fibres (Fig. 4E and F), suggesting that the Ca2+ binding properties of sTnC and near-neighbour RU interactions act independently of one another to influence kTR at low Ca2+. This results in an extended Ca2+ dependence (i.e. range) of kTR in native skeletal muscle. In other words, the Ca2+ binding kinetics of sTnC and near-neighbour RU interactions combine to slow kTR for tension levels less than 0.5 Fmax, and as Ca2+ increases and activates more RUs in the thin filament, these two processes become less limiting to the rate of tension development. At the individual RU level, crossbridge binding probability is probably related to time Ca2+ is bound to sTnC, but could also include mechanisms of crossbridge-facilitated additional crossbridge binding. However, detailed study at this level is beyond the scope of the current experiments.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that kTR in skeletal muscle is primarily determined within RUs of the thin filament, with minor contributions of near-neighbour RU interactions to reducing kTR at low Ca2+. Further, the Ca2+ binding kinetics of native sTnC act within RUs to allow for a large Ca2+-dependent range of tension development rates. Decreasing (current work) or increasing (Moreno-Gonzalez et al. 2007) koff increases low-Ca2+kTR and diminishes its Ca2+ dependence. Finally, we have demonstrated for the first time that increasing or decreasing koff can influence the duration of the slow, isometric phase of relaxation in skeletal myofibrils, and that increasing koff affects activation kinetics. Comparisons between fibre and myofibril data suggest that Ca2+ binding to sTnC may not limit the rate of tension rise during activation, but may influence the duration of relaxation. These data suggest that the Ca2+ dissociation kinetics of native sTnC are optimized both for maximizing the range of tension development kinetics over all activating levels of Ca2+ and for minimizing the duration of relaxation in skeletal muscle.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs Zhaoxiong Luo and An-Yue Tu for construction of sTnC mutants and preparation of sTn complexes, as well as Dr Bertrand C. W. Tanner, Dr Anita Beck and Alice Ward for steady-state tension–pCa and kTR,max data with I60Q sTnC in fibres. We thank Dr Albert M. Gordon for discussions and helpful comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by USA NIH grants HL65497 (M.R.) and HL61683 (M.R.), and Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca, Italy, grants PRIN2006 (C.T. and C.P.). K. L. Kreutziger is a recipient of a Graduate Fellowship in Biomedical Engineering from The Whitaker Foundation. M. Regnier is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association.

References

- Brandt PW, Colomo F, Piroddi N, Poggesi C, Tesi C. Force regulation by Ca2+ in skinned single cardiac myocytes of frog. Biophys J. 1998;74:1994–2004. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77906-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt PW, Diamond MS, Schachat FH. The thin filament of vertebrate skeletal muscle co-operatively activates as a unit. J Mol Biol. 1984;180:379–384. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. Technique for stabilizing the striation pattern in maximally calcium-activated skinned rabbit psoas fibers. Biophys J. 1983;41:99–102. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84411-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. Effect of Ca2+ on cross-bridge turnover kinetics in skinned single rabbit psoas fibers: implications for regulation of muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:3265–3269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B, Eisenberg E. Rate of force generation in muscle: correlation with actomyosin ATPase activity in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:3542–3546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalovich JM, Chock PB, Eisenberg E. Mechanism of action of troponin. tropomyosin. Inhibition of actomyosin ATPase activity without inhibition of myosin binding to actin. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:575–578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase PB, Kushmerick MJ. Effects of pH on contraction of rabbit fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1988;53:935–946. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase PB, Martyn DA, Hannon JD. Isometric force redevelopment of skinned muscle fibers from rabbit activated with and without Ca2+ Biophys J. 1994;67:1994–2001. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80682-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmens EW, Entezari M, Martyn DA, Regnier M. Different effects of cardiac versus skeletal muscle regulatory proteins on in vitro measures of actin filament speed and force. J Physiol. 2005;566:737–746. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomo F, Nencini S, Piroddi N, Poggesi C, Tesi C. Calcium dependence of the apparent rate of force generation in single striated muscle myofibrils activated by rapid solution changes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;453:373–381. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-6039-1_42. discussion 381–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomo F, Piroddi N, Poggesi C, te Kronnie G, Tesi C. Active and passive forces of isolated myofibrils from cardiac and fast skeletal muscle of the frog. J Physiol. 1997;500:535–548. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomo F, Poggesi C, Tesi C. Force responses to rapid length changes in single intact cells from frog heart. J Physiol. 1994;475:347–350. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzig JA, Goldman YE, Millar NC, Lacktis J, Homsher E. Reversal of the cross-bridge force-generating transition by photogeneration of phosphate in rabbit psoas muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1992;451:247–278. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Tombe PP, Belus A, Piroddi N, Scellini B, Walker JS, Martin AF, Tesi C, Poggesi C. Myofilament calcium sensitivity does not affect cross-bridge activation-relaxation kinetics. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1129–R1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00630.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W, Rosenfeld SS, Wang CK, Gordon AM, Cheung HC. Kinetic studies of calcium binding to the regulatory site of troponin C from cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:688–694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons DP, Patel JR, Campbell KS, Moss RL. Cooperative mechanisms in the activation dependence of the rate of force development in rabbit skinned skeletal muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:133–148. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis TE, Martyn DA, Rivera AJ, Regnier M. Investigation of thin filament near-neighbor regulatory unit interactions during skinned rat cardiac muscle force development. J Physiol. 2007;580:561–576. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes AV, Venkatraman G, Davis JP, Tikunova SB, Engel P, Solaro RJ, Potter JD. Cardiac troponin T isoforms affect the Ca2+ sensitivity of force development in the presence of slow skeletal troponin I: insights into the role of troponin T isoforms in the fetal heart. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49579–49587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AM, Homsher E, Regnier M. Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:853–924. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock WO, Huntsman LL, Gordon AM. Models of calcium activation account for differences between skeletal and cardiac force redevelopment kinetics. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1997;18:671–681. doi: 10.1023/a:1018635907091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress M, Huxley HE, Faruqi AR, Hendrix J. Structural changes during activation of frog muscle studied by time-resolved X-ray diffraction. J Mol Biol. 1986;188:325–342. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutziger KL, Gillis TE, Davis JP, Tikunova SB, Regnier M. Influence of enhanced troponin C Ca2+ binding affinity on cooperative thin filament activation in rabbit skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2007;583:337–350. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutziger KL, Gillis TE, Tikunova SB, Regnier M. Effects of TnC with increased Ca2+ affinity on cooperative activation and force kinetics in skeletal muscle. Biophys J. 2004;86:213a. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutziger KL, Piroddi N, Belus A, Scellini B, Poggesi C, Regnier M. Effect of TnC with altered Ca2+ binding kinetics on force generation in striated muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2006;27:501–502. [Google Scholar]

- Li MX, Wang X, Sykes BD. Structural based insights into the role of troponin in cardiac muscle pathophysiology. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2004;25:559–579. doi: 10.1007/s10974-004-5879-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Love ML, Putkey JA, Cohen C. Bepridil opens the regulatory N-terminal lobe of cardiac troponin C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5140–5145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090098997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Davis JP, Smillie LB, Rall JA. Determinants of relaxation rate in rabbit skinned skeletal muscle fibers. J. Physiol. 2002;545:887–901. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLachlan LK, Reid DG, Mitchell RC, Salter CJ, Smith SJ. Binding of a calcium sensitizer, bepridil, to cardiac troponin C. A fluorescence stopped-flow kinetic, circular dichroism, and proton nuclear magnetic resonance study. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9764–9770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn DA, Chase PB, Hannon JD, Huntsman LL, Kushmerick MJ, Gordon AM. Unloaded shortening of skinned muscle fibers from rabbit activated with and without Ca2+ Biophys J. 1994;67:1984–1993. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80681-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn DA, Chase PB, Regnier M, Gordon AM. A simple model with myofilament compliance predicts activation-dependent crossbridge kinetics in skinned skeletal fibers. Biophys J. 2002;83:3425–3434. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75342-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger JM, Moss RL. Calcium-sensitive cross-bridge transitions in mammalian fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. Science. 1990;247:1088–1090. doi: 10.1126/science.2309121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger JM, Moss RL. Kinetics of a Ca2+-sensitive cross-bridge state transition in skeletal muscle fibers. Effects due to variations in thin filament activation by extraction of troponin C. J Gen Physiol. 1991;98:233–248. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Gonzalez A, Fredlund J, Regnier M. Cardiac troponin C (TnC) and a site I skeletal TnC mutant alter Ca2+ versus crossbridge contribution to force in rabbit skeletal fibres. J Physiol. 2005;562:873–884. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Gonzalez A, Gillis TE, Rivera AJ, Chase PB, Martyn DA, Regnier M. Thin-filament regulation of force redevelopment kinetics in rabbit skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2007;579:313–326. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CA, Tobacman LS, Homsher E. Modulation of contractile activation in skeletal muscle by a calcium-insensitive troponin C mutant. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20245–20251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piroddi N, Tesi C, Pellegrino MA, Tobacman LS, Homsher E, Poggesi C. Contractile effects of the exchange of cardiac troponin for fast skeletal troponin in rabbit psoas single myofibrils. J Physiol. 2003;552:917–931. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.051615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggesi C, Tesi C, Stehle R. Sarcomeric determinants of striated muscle relaxation kinetics. Pflugers Arch. 2005;449:505–517. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]