Abstract

Back-propagating action potentials (bAPs) travelling from the soma to the dendrites of neurons are involved in various aspects of synaptic plasticity. The distance-dependent increase in Kv4.2-mediated A-type K+ current along the apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal cells (CA1 PCs) is responsible for the attenuation of bAP amplitude with distance from the soma. Genetic deletion of Kv4.2 reduced dendritic A-type K+ current and increased the bAP amplitude in distal dendrites. Our previous studies revealed that the amplitude of unitary Schaffer collateral inputs increases with distance from the soma along the apical dendrites of CA1 PCs. We tested the hypothesis that the weight of distal synapses is dependent on dendritic Kv4.2 channels. We compared the amplitude and kinetics of mEPSCs at different locations on the main apical trunk of CA1 PCs from wild-type (WT) and Kv4.2 knockout (KO) mice. While wild-type mice showed normal distance-dependent scaling, it was missing in the Kv4.2 KO mice. We also tested whether there was an increase in inhibition in the Kv4.2 knockout, induced in an attempt to compensate for a non-specific increase in neuronal excitability (after-polarization duration and burst firing probability were increased in KO). Indeed, we found that the magnitude of the tonic GABA current increased in Kv4.2 KO mice by 53% and the amplitude of mIPSCs increased by 25%, as recorded at the soma. Our results suggest important roles for the dendritic K+ channels in distance-dependent adjustment of synaptic strength as well as a primary role for tonic inhibition in the regulation of global synaptic strength and membrane excitability.

The densities and modulatory states of ligand- and voltage-gated ion channels vary within dendritic arbors (Migliore & Shepherd, 2002). In CA1 pyramidal neurons the more distal dendritic regions exhibit both a reduced membrane excitability (due to increased voltage-gated K+ and hyperpolarization-activated cation channel densities) (Hoffman et al. 1997; Magee, 1998) and an elevated excitatory input (due to increases in AMPA receptor densities and other synaptic alterations) (Andrásfalvy & Magee, 2001; Smith et al. 2003) while inhibitory input remains constant (Andrásfalvy & Mody, 2006). This sub-cellular level of interaction between membrane excitability and synaptic input efficacy is reminiscent of that observed at the cellular level for homeostatic scaling (Turrigiano et al. 1998; Desai et al. 1999; van Welie et al. 2004).

Although previous studies have investigated the molecular mechanisms of this distance-dependent synaptic scaling in detail (Magee & Cook, 2000; Smith et al. 2003; Andrásfalvy et al. 2003), the identity of the signal representing dendritic location (with respect to the soma) of a particular synapse is unknown. One likely candidate is the back-propagating action potential (bAP), which decreases in amplitude as it propagates away from the soma and into the dendritic arbor of pyramidal neurons (Johnston et al. 1999; Frick et al. 2004; Gasparini et al. 2007). This amplitude decrease is generally thought to be a consequence of the severalfold increase in dendritic voltage-gated K+ channel density along the dendrite (Hoffman et al. 1997). A-type transient K+ currents mediated by Kv4.2 subunit-containing channels play a primary role in this regulation (Hoffman et al. 1997; Kim et al. 2005). Importantly, these voltage-gated channels are subject to voltage-dependent inactivation, and are targets of several neuromodulatory systems (Hoffman et al. 1997; Hoffman & Johnston, 1999; Pan & Colbert, 2001; Ramakers & Storm, 2002; Frick et al. 2004). Additionally, bAPs are involved in associative synaptic plasticity and the modulation of general dendritic excitability, adjusting the properties and expression level of voltage- and ligand-gated ion channels putatively through Ca2+-activated messenger cascades (Hoffman & Johnston, 1998; Frick et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2007). Furthermore, a recent study revealed the activity-dependent trafficking and surface expression of Kv4.2 channels in CA1 neurons (Kim et al. 2007). Thus, the bAP and the Ca2+ influx associated with it could be a dynamically regulated signal between the output and input regions of pyramidal neurons.

To investigate the role of dendritic K+ channels and by implication of bAPs in the distance-dependent regulation of synaptic weight, we performed experiments on a transgenic mouse line in which the Kv4.2 gene has been silenced (Chen et al. 2006) resulting in almost complete elimination of dendritic A-type K+ currents and substantial enhancement of the bAP amplitude in the distal dendritic arbor. We show that distance-dependent scaling of local miniature AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic currents is severely perturbed in CA1 pyramidal cells in the absence of Kv4.2. Distal mEPSC amplitude was found to be significantly reduced compared to that in wild-type littermates, whereas proximal mEPSC amplitude was not significantly altered. Surprisingly, despite the loss of a major K+ current, excitability of CA1 pyramidal cells was only slightly altered in Kv4.2 knockout animals (see also Hoffman et al. 1997; Bernard et al. 2004). However, this could be explained by increased GABAergic inhibition, as we found that both the tonic GABA receptor current and phasic mIPSCs amplitude was significantly elevated in cells from knockout mice. These results strongly support a major role for A-type K+ channels in distance-dependent adjustment of synaptic strength as well as a primary role for tonic inhibition in the regulation of global synaptic strength and membrane excitability. Finally, these data indicate that a fine adjustment of excitation, inhibition and intrinsic properties enable neurons to maintain their normal input–output function even in the face of a severe perturbation.

Methods

Transgenic animals and genotyping

Kv4.2−/− mice were generated in a 129/SvEv background (Guo et al. 2005). Littermate genotypes were confirmed by PCR results on the basis of Kv4.2-specific primers (Chen et al. 2006). Most of the mEPSC and GABA recordings, as well as approximately half of the excitability experiments, were performed blind as to genotype.

Hippocampal slice preparation and electrophysiology

Transverse hippocampal slices (350 μm) were prepared from 42- to 90-day-old male Kv4.2−/− mice and wild-type littermates (WT). According to methods approved by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Janelia Farm Research Campus and University of Texas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, animals were anaesthetized by lethal dose of isoflurane inhalation and perfused through the heart with ice-cold cutting solution containing (mm): 234 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 7 dextrose, bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2 at ∼0°C (pH 7.4). Brains were rapidly removed after decapitation and placed in cold oxygenated cutting solution. Slices were prepared using a vibratome (Vibratome, St Louis, MO, USA), and subsequently kept in ACSF, as normal external solution (see later), for 30 min at 37°C, and then at room temperature. Experiments were conducted from the soma or apical trunk of CA1 pyramidal cells visualized using an upright Zeiss Axioskop microscope fitted with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics using infrared illumination. When recording from dendrites, unless otherwise specified, the proximal recording location corresponded to a position where dendritic spine density had become substantial (50–80 μm from soma), whereas the distal location was at 180–230 μm from soma (approximately 30 μm proximal from the termination of the stratum radiatum). Patch pipettes (5–8 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass and filled with different intracellular solutions as specified below. The normal external solution contained (mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 dextrose, bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2 at ∼33°C (pH 7.4). All neurons had resting potentials between −55 and −70 mV. Series resistances from dendritic whole-cell recordings were between 10 and 40 MΩ.

Dendritic recording of synaptic AMPA currents

Patch pipettes were filled with an internal solution containing (mm): 120 potassium gluconate, 20 KCl, 0.5 EGTA, 4 NaCl, 0.3 CaCl2, 4 Mg2ATP, 0.3 Tris2GTP, 14 phosphocreatine and 10 Hepes (pH 7.25). Local unitary synaptic events were evoked by pressure ejection of a hyperosmotic external solution (with the addition of 300 mm sucrose), containing tetrodotoxin (TTX, 0.5 μm) and Hepes (10 mm) replacing NaHCO3 (∼700 mosm l−1). AMPA currents were further isolated using the NMDA receptor antagonist d-aminophosphonovalerate (APV; 50 μm) and the ionotropic GABA receptor antagonist (+)-bicuculline (20 μm) in the external solution. Currents were recorded at −70 mV using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, filtered at 3 or 5 kHz and digitized at 10 or 50 kHz. Miniature EPSCs crossing an approximate 4 pA threshold level were selected for further examination using a template-fitting algorithm written in Igor Pro (Magee & Cook, 2000; Smith et al. 2003). For precise kinetic analysis, we used the 50 kHz dataset. Events were fitted with a sum of two exponential functions to obtain peak amplitude, rise and decay-time constants. Events that had rise-time constants larger than 400 μs were eliminated from analysis since these events were unlikely to be generated by local synapses (Magee & Cook, 2000; Smith et al. 2003). Amplitude histograms were constructed from between 50 and 300 (typically 100–150) unitary events.

Somatic recording of tonic and phasic GABA currents

Patch pipettes (5–8 MΩ) were filled with an internal solution containing (mm): 140 CsCl, 0.5 EGTA, 4 NaCl, 0.3 CaCl2, 4 Mg2ATP, 0.3 Tris2GTP, 14 phosphocreatine and 10 Hepes (pH 7.25). GABA (5 μm, Tocris) and the GAT-1 GABA uptake blocker NO-711 (10 μm, Tocris) were added to the normal external solution and slices were preincubated in this solution for 30 min before starting whole-cell recordings. GABA currents were isolated using APV (50 μm) and the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX (5 μm) together with TTX (0.5 μm) in the external solution. In experiments measuring the tonic GABA current, currents were recorded at −70 mV using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. The magnitude of the tonic GABA current was determined by bicuculline methiodide (BMI, 200 μm) application using a custom-made fast bath application system. BMI was used instead of (+)-bicuculline in these experiments because its good water solubility allowed the use of higher concentrations. Values of the mean current were measured in 10 s recording segments (before and after BMI application) and used to construct a histogram (bin-width 1 pA). Due to the presence of spontaneously occurring miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) the histogram had a skewed distribution toward large negative values, therefore we used the unskewed portion of the distribution with a Gaussian fit to measure only the tonic current. Igor Pro was used for analysis, similarly to as described previously (Glykys & Mody, 2006). For spontaneously occurring mIPSCs, recordings were sampled at 50 kHz and filtered at 5 kHz. mIPSCs crossing an approximate 4 pA threshold level were selected for further examination using a template-fitting algorithm written in Igor Pro (Magee & Cook, 2000; Smith et al. 2003), and analysed further as described for mEPSCs.

Somatic excitability recording

Experiments were performed in ACSF containing (mm): 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 1.3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 dextrose, bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2 at ∼33–36°C (pH 7.4). Current-clamp whole-cell recordings from somata were performed using a Dagan BVC-700 amplifier in the active ‘bridge’ mode, filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at 50 kHz. Patch pipettes had a resistance of 2–6 MΩ when filled with a solution containing (mm): 120 potassium gluconate, 20 KCl, 4 NaCl, 4 Mg2ATP, 0.3 Tris2GTP, 14 phosphocreatine and 10 Hepes (pH 7.25). Pipette solution additionally contained 50 μm Alexa 488 hydrazide (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) to visualize and identify the cell with two-photon microscopy (Prairie Technologies, Middleton, WI, USA). To avoid artifacts of imperfect capacitive compensation we used 200 pA, 900 ms current injection to analyse 1st spike properties. Only the fast (< 50 ms) onset-time 1st spikes were analysed, to avoid significant Na+ channel desensitization. In some somatic excitability recordings (+)-bicuculline (20 μm) was used to block ionotropic GABA receptors, and to avoid unwanted SK channel blockade by methyl derivative of bicuculline (like BMI, Debarbieux et al. 1998).

Data are reported as means ±s.e.m. Statistical comparisons were performed using two-sample Student's t test, two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, or two-way repeated measures ANOVA (for after-polarization and half-width of AP comparisons in WT and KO). Differences were considered to be significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Altered properties of mEPSCs

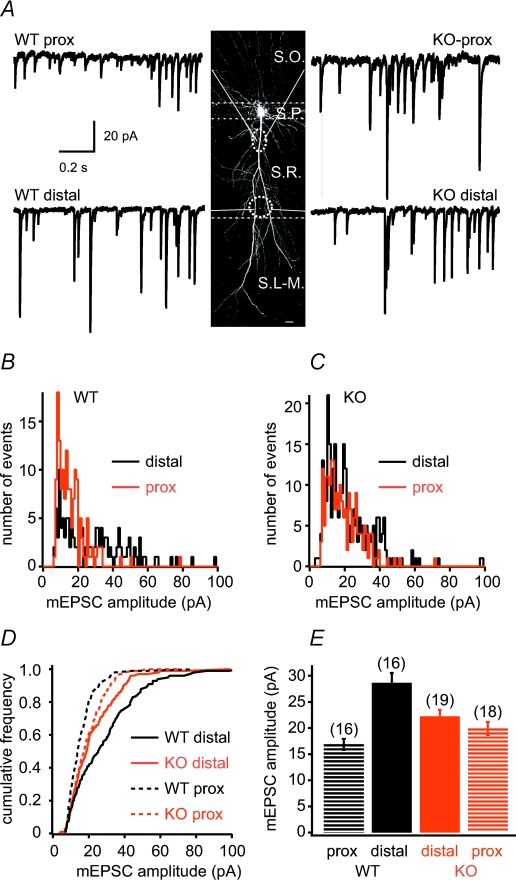

We began by assessing the impact of Kv4.2 deletion on dendritic AMPA receptor-mediated miniature synaptic currents (mEPSCs). To do so we performed dendritic whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings at proximal (∼50–80 μm from soma) and distal (∼180–230 μm) locations and compared the amplitude and kinetics of mEPSCs evoked by local application of a high osmotic solution from both wild-type (WT) and Kv4.2−/− (KO) mice (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous data obtained from rats (Magee & Cook, 2000; Smith et al. 2003) and mice (Andrasfalvy et al. 2003; Andrasfalvy & Mody, 2006), distal mEPSCs amplitudes in WT mice were significantly larger than proximal events (WT proximal: 16.88 ± 1.17 pA, n = 16; WT distal: 28.62 ± 1.91 pA, n = 16; P < 0.001, Fig. 1A, B, D and E). In contrast, we found that the distal mEPSC amplitude was significantly smaller in KO cells than that in WT cells (KO distal: 22.22 ± 1.23 pA, n = 19; P < 0.01; Fig. 1C and E), whereas the amplitude of mEPSCs at the proximal location tended to increase in KO mice, although this difference was not statistically significant (KO proximal: 19.92 ± 1.22 pA, n = 18; P > 0.05, Fig. 1C and E). As a result of these changes, there was no significant increment of mEPSC amplitude from proximal to distal location in KO mice (P > 0.05). Thus, distance-dependent synaptic scaling is missing in CA1 pyramidal neurons of Kv4.2−/− mice.

Figure 1. Distance-dependent scaling of synaptic current amplitude is altered in Kv4.2−/− mice.

A, middle, two-photon image stack spanning the entire apical dendritic arborization of a CA1 pyramidal neuron. Dashed lines indicate the approximate borders of stratum oriens (S.O.), pyramidale (S.P.), radiatum and lacunosum-moleculare (S.L.-M.). Ovals represent distal and proximal recording sites in stratum radiatum (S.R.). Left and right, representative recordings of hypertonically evoked miniature AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic currents from proximal and distal dendrites in wild-type (WT, left) and Kv4.2 knockout (KO, right) mice. B and C, mEPSC amplitude distribution of proximal and distal synapses from representative cells of WT and KO mice. D, cumulative frequency distribution of 130–260 individual mEPSCs from each of the recordings shown in A. E, group data of mean mEPSC amplitudes for all cells.

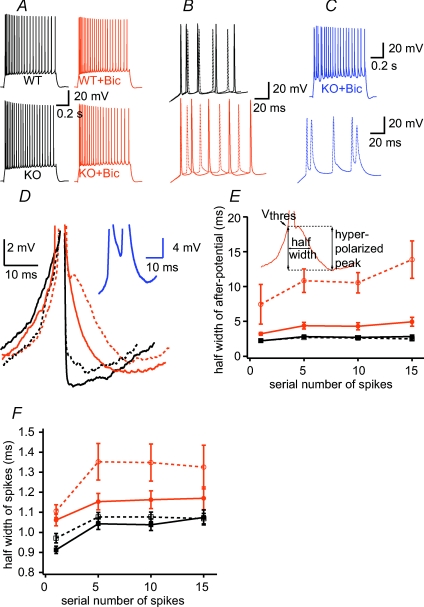

Figure 3. Spike properties are altered in KO mice.

A–C, representative recordings using +200 pA current injection in control and bicuculline (Bic)-treated cells from both strains. B, magnified traces of A. C, burst firing traces at KO neurons in the presence of Bic. D, magnified traces show differences in after-potential under different conditions. Line coding is same as Fig. 2. Blue inset trace shows burst firing spikes. E, summary of the half-width of after-polarization. Note that after-polarization was more prominent in KO cells, and increased more in bicuculline, than in WT neurons. Inset shows the measurement of parameters as the half of the interval between the thresholds of certain (1st, 5th, 10th, 15th) APs and the most hyperpolarized value following the spike. F, the half-width of action potential is increased in KO mice and is more affected by bicuculline treatment. Data are from n = 9–23 cells per group in E–F.

Analysing the kinetic properties of mEPSCs, the 20–80% rise time was similar in WT and KO mice at the proximal (WT proximal: 185.8 ± 4.3 μs, n = 9; KO proximal: 211.1 ± 10.0 μs, n = 7, P > 0.05), and distal locations (WT distal: 204.8 ± 9.3 μs, n = 10; KO distal: 208.2 ± 11.0 μs, n = 10, P > 0.05). Consistent with values previously reported, decay times (WT proximal: 4.48 ± 0.19 ms, n = 8; KO proximal: 4.68 ± 0.16 ms, n = 8, P > 0.05; WT distal: 3.52 ± 0.10 ms, n = 10; KO distal: 3.76 ± 0.13 ms, n = 10, P > 0.05) of distal mEPSCs were faster compared to that of proximal events (P < 0.01 for both) in both genetic groups, a difference that is likely to be attributed to an effect of dendritic morphology (Magee & Cook, 2000; Smith et al. 2003).

Although distance-dependent synaptic scaling was indeed eliminated in KO mice, our hypothesis predicted that the loss of Kv4.2 should remove scaling by severely reducing the distal mEPSC amplitude while less prominently but also decreasing proximal mEPSC amplitude (Andrasfalvy et al. 2003; Frick et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2006; Fig. 5A). However, our results showed that although distal mEPSC amplitudes indeed decreased, proximal mEPSC amplitudes were not reduced as expected, but rather a slight (although by itself not statistically significant) increasing tendency of amplitude contributed to the elimination of distance-dependent scaling in Kv4.2 KO.

Figure 5. Inverse correlation between bAP amplitude (and the bAP-induced Ca2+ signal) and the local mEPSC amplitude along the main apical dendrite.

A, our current mEPSC results (symbols) are presented combined with previous bAP and Ca2+ data (Frick et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2006). In wild-type cells, as the amplitude of bAP decreases with distance from soma, the Ca2+ signal is also attenuating (black dotted line), while the mEPSC amplitude is increasing (black continuous line). Blue line indicates the theoretical prediction of the amplitude of mEPSCs in Kv4.2 KO mice, based on the decreased attenuation of bAP and Ca2+ signal in KO mice (red dotted line). In contrast to our prediction of decreased mEPSC amplitude both at proximal and distal locations (albeit with different magnitude), the amplitude of proximal mEPSCs was not changed or even slightly tended to increase relative to the WT, while that of distal mEPSCs was decreased (red continuous line). This may be due to an increase in inhibition attempting to compensate for a non-specific increase in neuronal excitability in the Kv4.2 mice. Dark green lines indicate the amplitude of tonic GABA currents in WT (continuous) and KO (dashed) cells. Bright green line represents the elevation of mEPSC amplitude from the predicted to the measured value by the difference of KO versus WT tonic GABA currents (black arrow). The modified prediction of the mEPSC amplitude in KO mice is now in good agreement with the measured data. B, comparison of mEPSC amplitude changes in Kv4.2 KO (current study) and GluR1 KO mice (Andrasfalvy et al. 2003), another strain lacking of distance-dependent scaling. In GluR1 KO cells a similar scaling shift has been detected (Andrasfalvy et al. 2003).

Membrane excitability measurements

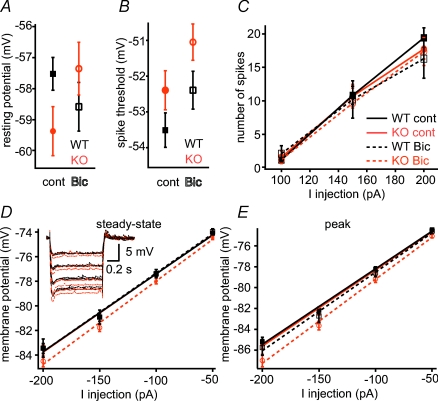

To understand this, we further investigated the excitability and firing patterns of CA1 pyramidal neurons using whole-cell current-clamp experiments. Based on previous experimental results using pharmacological blockade of A-type K+ currents (Hoffman et al. 1997; Bernard et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2005), a decreased number of functional Kv4.2 channels is expected to greatly enhance membrane excitability. Indeed, a few differences were observed in membrane parameters, as somatic AP amplitude (WT: 77.63 ± 2.14 mV, n = 17; KO: 87.86 ± 2.05 mV, n = 15, P < 0.05, Table 1) and AP half-width (P < 0.01; Fig. 3F) were larger in KO mice, and spike after-polarization half-width (after-polarization amplitude defined as the difference between the AP threshold and the most hyperpolarized point after AP, Fig. 3E inset) was longer in KO neurons (P < 0.001; Fig. 3D and E). Yet, under control conditions most measures of membrane excitability were not different (action potential threshold, spike latencies, input resistance, evoked AP numbers, see Fig. 2 and Table 1) and resting membrane potential (Vrest) was marginally hyperpolarized in KO cells compared to WT (WT: −57.52 ± 0.52 mV, n = 21; KO: −59.36 ± 0.79 mV, n = 19, P = 0.05). Thus, in general, the membrane excitability of KO cells did not appear to be fundamentally enhanced under control conditions.

Table 1.

Intrinsic membrane and spike properties of CA1 pyramidal cells from WT and KO mice in control solution and during bicuculline administration

| WT | KO | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Bicuculline | Control | Bicucculine | |

| Vrest (mV) | −57.52 ± 0.52 | −58.58 ± 0.70 | −59.36 ± 0.79 | −57.35 ± 0.74 |

| (n = 21) | (n = 12) | (n = 19) | (n = 14) | |

| Vthres (mV) | −53.51 ± 0.48† | −52.39 ± 0.53 | −52.39 ± 0.54 | −51.04 ± 0.50 |

| (n = 15) | (n = 10) | (n = 16) | (n = 10) | |

| Amplitude of 1st spike (mV) | 77.63 ± 2.14* | 76.96 ± 4.73 | 87.86 ± 2.05 | 80.43 ± 5.87 |

| (n = 17) | (n = 8) | (n = 15) | (n = 11) | |

| Onset time of 1st spike (ms) | 41.52 ± 4.27 | 41.07 ± 9.46 | 45.63 ± 9.23 | 55.69 ± 16.67 |

| (n = 21) | (n = 8) | (n = 19) | (n = 14) | |

| Steady-state (MΩ) | 63.34 ± 2.30 | 63.89 ± 0.32 | 63.00 ± 1.54 | 67.75 ± 2.44 |

| (n = 21) | (n = 12) | (n = 19) | (n = 14) | |

| Peak (MΩ) | 72.53 ± 2.08 | 76.92 ± 4.31 | 73.02 ± 1.95 | 80.58 ± 3.06 |

| (n = 21) | (n = 12) | (n = 19) | (n = 14) | |

Results of statistical analysis are indicated with different symbols:

P < 0.05, *WT-KO,

P < 0.05, †WT-KO+Bic.

Figure 2. Altered intrinsic membrane properties in Kv4.2−/− mice.

A, resting membrane potential is lower in KO under control conditions, but this difference is eliminated in the presence of bicuculline (Bic). B, spike threshold is not different between WT (black lines) and KO (red lines). C, input–output relationship is similar in WT and KO. D and E, voltage responses to hyperpolarizing current injections are differentially affected by bicucullin (dashed lines) in KO cells.

Firing properties without inhibition

These results were somewhat unexpected and indeed different from previous data showing increased excitability by acute pharmacological blockade of Kv4.2 channel (Magee & Carruth, 1999), in neurons from slice culture (Kim et al. 2005) and by acute expression of a dominant negative version of Kv4.2 (Kim et al. 2007). We therefore hypothesized that long-term down-regulation of Kv4.2-mediated currents through genetic deletion induced a compensatory mechanism to restore normal excitability of the cell. A likely candidate for such compensation could be an increase of GABAergic inhibition. To test this idea, we measured the intrinsic properties of WT and KO cells in the presence of the GABA-A receptor blocker bicuculline (20 μm, Bic). In the presence of Bic, Vrest of KO cells was slightly more depolarized than under control conditions (Table 1), whereas Bic had no effect in WT cells (Table 1; Fig. 2A and B). As a result, the difference in Vrest of WT and KO cells was eliminated in Bic (P > 0.05). The AP amplitude also became similar in both groups (Table 1). The most dramatic effect of the blockade of GABAergic inhibition was seen on the AP after-potential, which was markedly increased in KO neurons (Fig. 3E; the effect was more prominent at later AP after-potentials in the train), but not in WT cells (Fig. 3E; P < 0.001). The duration of the after-potential increased to such a degree in KO neurons that most neurons (7 out of 13) now showed burst firing in Bic, in contrast to WT cells where bursting was never observed (Fig. 3). Similarly, AP half-width increased stronger in KO than in WT cells, especially in the later APs in the train (Fig. 3F; P < 0.001). Together these data indicate that excitability of KO neurons was more effectively attenuated by inhibition than that of WT cells, suggesting that GABAergic inhibition was enhanced in Kv4.2 KO mice. We next aimed to directly determine this change in details by studying tonic and phasic GABAergic currents in the two genetic groups.

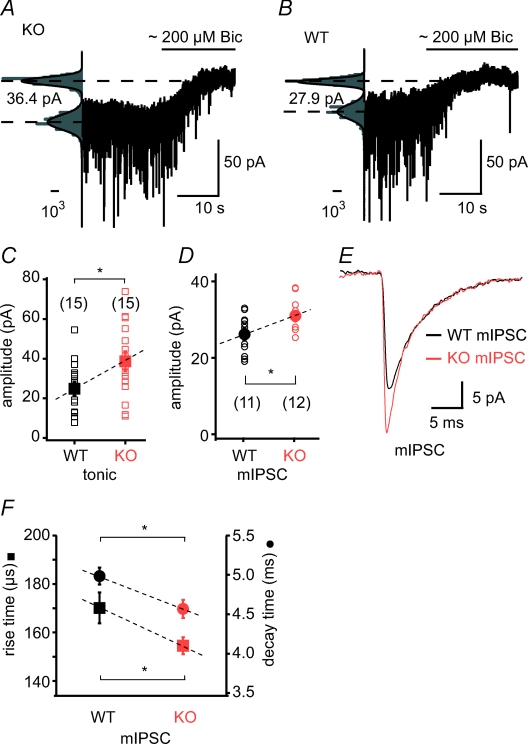

Elevated tonic and phasic inhibition

To optimize conditions for measurement of tonic inhibition (Glykys & Mody, 2006), we used an intracellular solution containing 140 mm CsCl instead of potassium gluconate and KCl to adjust the Cl− reverse potential close to 0 mV and block most of the K+ currents. We preincubated the slices in 5 μm GABA and 10 μm GABA uptake blocker (see Methods). After a stable holding current was obtained, we injected a high concentration (∼200 μm) of bicuculline methiodide (BMI) using a fast application system to rapidly block ionotropic GABA receptors. Tonic GABA current was measured as the difference between the holding current before and after BMI application. These experiments revealed that the tonic GABA current was substantially elevated in KO mice (WT: 24.79 ± 3.55 pA, n = 15; KO: 38.65 ± 5.04 pA, n = 15, P < 0.05, Fig. 4A and B). Thus, increased tonic inhibition could be one of the effective counterbalancing mechanisms of the loss of Kv4.2 channels (Bonin et al. 2007).

Figure 4. Tonic and phasic GABAergic currents are increased in Kv4.2 knockout mice.

A and B, representative recordings of holding current changes before and after application of bicuculline (Bic) in KO (A) and WT (B) cells. Scale bars represent the number of counts in 1 pA bins (total number of counts was 105 for the 10-long trace with 10 kHz sampling rate). C and D, group data of the amplitude of tonic inhibition (C) and of mIPSC amplitude (D) in WT and KO mice. E, average mIPSC traces from the recordings shown in A and B (150 and 260 events, respectively). F, kinetic properties (rise time: squares; decay times: circles) of mIPSCs are faster in KO mice, suggesting a possible subunit composition shift. * indicates P < 0.05.

To examine whether phasic synaptic inhibition was also different in Kv4.2 KO cells, we analysed the amplitude and kinetic properties of spontaneously occurring mIPSCs in the presence of TTX in somatic recordings. The amplitude of fast mIPSCs (20–80% rise-time < 400 μs), presumably arriving to the perisomatic region, was significantly elevated in KO mice (WT: 26.14 ± 1.64 pA, n = 11; KO: 30.98 ± 1.29 pA, n = 12, P < 0.05, Fig. 4C and D). Also, the rise and decay times of mIPSCs were faster in KO cells (rise-time: WT: 170.1 ± 6.37 μs; KO: 154.4 ± 3.51 μs, P < 0.05; decay time: WT: 4.98 ± 0.10 ms; KO: 4.56 ± 0.11 ms, P < 0.05, Fig. 4F). In both cell groups, the frequency of spontaneously occurring mIPSCs was similar (WT: 13.21 ± 1.91 Hz, n = 15; KO: 16.33 ± 2.15 Hz, n = 15, P > 0.05), and comparable to that previously observed by somatic patching (Andrasfalvy & Mody, 2006). In summary, we found that the amplitude of both tonic and phasic GABAergic currents were increased in CA1 pyramidal neurons of Kv4.2 KO mice compared to that in WT cells, confirming that enhanced inhibition acts to counterbalance increases in excitability resulting from the loss of Kv4.2-mediated K+ currents.

Discussion

In this study we found that: (1) distance-dependent synaptic scaling is absent in Kv4.2 KO mice in which bAP attenuation is prominently decreased; (2) mEPSC amplitude is larger than expected based on our correlation model (Fig. 5A) in the Kv4.2 KO mice; (3) tonic and phasic GABAergic inhibition is elevated in Kv4.2 KO mice; and (4) the enhanced GABAergic inhibition reduces the membrane excitability in these mice to a level that approximates that found in WT neurons. Together these data suggest that the normal signals provided by decremental bAPs act to elevate distal excitatory synaptic inputs delivered by the Schaffer collaterals. When this signal is missing, as in the Kv4.2−/− mice, there is no increase in the efficacy of distal Schaffer collateral input compared to proximal ones. Furthermore, our data show that GABAergic inhibition is elevated in what is perhaps a homeostatic response to the increased membrane excitability brought about by the loss of the normally prominent transient outward current in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Finally, it appears that the overall level of excitatory synaptic input is also elevated, albeit without any distance dependence, as perhaps yet another homeostatic response to the elevated inhibition (Fig. 5A).

Backpropagating action potentials and synaptic scaling

bAPs in CA1 pyramidal neurons of Kv4.2 knockout mice attenuate much less with distance than in WT mice (Chen et al. 2006) and are accompanied by a substantial Ca2+ signal that is mainly the result of influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC) and NMDA receptors. As expected, this Ca2+ influx decreases with distance along with the decrease in bAP amplitude (Magee & Johnston, 1997; Frick et al. 2003, 2004; Chen et al. 2006). This correlation with distance raises the possibility that the bAP-induced Ca2+ influx might serve as a signal for adjusting the synaptic strength of distal synapses. According to our hypothesis (Fig. 5A), bAP-associated Ca2+ influx restricts the incorporation of AMPA receptors into synapses and therefore under normal conditions the progressively smaller Ca2+ influx at more distal locations would be less restrictive to AMPA receptor insertion, resulting in larger mEPSCs. In Kv4.2 knockouts, the bAP-evoked Ca2+ signal is still quite large in the most distal dendritic regions and therefore reducing AMPA receptor insertion accordingly, with weaker mEPSCs as a result.

Ca2+ acting as an intracellular messenger in the regulation of synaptic strength has been implicated in several forms of synaptic plasticity. It is widely accepted that in Hebbian-type plasticity (including spike timing-dependent plasticity) the direction of synaptic efficacy changes depends on the magnitude and dynamics of the NMDA- and VGCC-mediated Ca2+ influx (Kirkwood et al. 1993; Magee & Johnston, 1997; Markram et al. 1997; Dan & Poo, 2004). Also, NMDAR-dependent spontaneous synaptic activity has a crucial role in maintaining synaptic strength (Sutton et al. 2004). Lack of NMDAR-dependent spontaneous activity could induce a fast increase of synaptic AMPA receptor enhancement, similarly to that evoked by inhibition of firing activity which acts, however, at a slower timescale (Turrigiano et al. 1998; Sutton et al. 2004). A recent study showed homeostatic regulation of AMPA receptor expression in single synapses, regulated by Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors (Hou et al. 2008). These observations also support the idea of activity-dependent maintenance of synaptic scaling as a homeostatic plasticity at both the single synapse level as well as in the entire cell. Distance-dependent synaptic scaling might have a similar Ca2+-dependent mechanism mediated by NMDAR and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels.

Although the above interpretation is consistent with the hypothesis that bAPs provide a distant-dependent signal to excitatory synapses we cannot exclude the possibility that factors other than bAPs were involved in elimination of distance-dependent synaptic scaling in the KO mice used here. These other factors include developmental or homeostatic changes induced by the loss of Kv4.2 or even simply that the normally present subcellular gradient of Kv4.2 is itself directly responsible for synaptic scaling. Future experiments using alternative approaches to more directly examine the role of bAPs and associated Ca2+ influx in synaptic scaling are currently under development.

Excitability and firing properties

Acute pharmacological and genetic down-regulation of Kv4.2 channels in wild-type cells resulted in pronounced increase of excitability (Kim et al. 2005, 2007). We also observed an elevation in membrane excitability once GABA-A receptor-mediated inhibition was eliminated, suggesting that GABAergic inhibition was enhanced in Kv4.2 KO cells. Elevation of tonic inhibition seems to be suitable for decreasing neuronal excitability (Bonin et al. 2007), although increases in other K+ channels have been reported to occur in cortical pyramidal neurons to compensate for the lack of Kv4.2 in KO animals (Nerbonne et al. 2008). Interestingly, in cerebellar Purkinje cells the increased excitability resulting from genetic elimination of the tonic GABA current has been counterbalanced by compensatory overexpression of TASK K+ channels (Brickley et al. 2001). Distribution of tonic inhibition seems to be homogenous in the dendritic and somatic region based on α5 subunit immunostaining (Prenosil et al. 2006) and unpublished electrophysiological recordings (C. Bernard, personal communication). In CA1 pyramidal neurons the α5 and δ subunits are responsible for tonic GABA currents (Glykys et al. 2008); therefore, it is likely that the elevated expression level of these subunits lies behind the increased tonic currents in KO mice. Properties of miniature synaptic GABAergic currents are also similar along the somato-dendritic axis in control mice (Andrasfalvy & Mody, 2006). The elevated mIPSCs with faster kinetic could be the result of higher α1 subunit expression level, based on developmental and genetic manipulation studies (Poulter et al. 1992; Goldstein et al. 2002; Prenosil et al. 2006). Activity-dependent changes in subunit densities and/or composition can be brought about by processes like activity-dependent GABA receptor ubiquitylation and degradation in ER (Saliba et al. 2007) or phosphorylation-dependent, clathrin-mediated receptor endocytosis (Kittler et al. 2000). An increase of inhibition is most probably one of the first reactions in response to elevated neuronal activity, where the homeostatic inhibitory regulation seems to be influenced by the elevated network activity rather than cellular activity (Hartman et al. 2006).

The elevated tonic GABA current, however, also decreases the impact of every mEPSC on somatic output. Presumably, some other mechanisms should increase the local mEPSC amplitude proportionally with the elevated inhibition to re-establish the normal input–output ratio of the cell. In our model (Fig. 5A) the shift of the predicted mEPSC amplitude curve by the elevated tonic inhibition showed a very close estimate to the measured data. What mechanisms are capable of readjusting the synaptic strength in the situation of the elevated inhibitory state? Based on studies on homeostatic plasticity (Turrigiano et al. 1998; Desai et al. 2002), elevated inhibition could decrease cellular excitability and in turn induce upscaling of excitatory synapses to regain a normal input–output ratio. The same mechanism could be responsible for the increase of synaptic efficacy in the entire dendritic arbor in Kv4.2 KO mice, as we proposed above. Similarly, elevated miniature EPSCs were reported in cultured neurons with somatic recording, when a dominant negative form of Kv4.2 channel was overexpressed (Kim et al. 2005). Such a general increase of synaptic efficacy may explain why the amplitude of proximal mEPSCs was not reduced (rather increased, if anything) together with the elimination of distance-dependent scaling, in contrast to what our theoretical model predicted. At distal location, this slight general increase of mEPSC amplitude would be combined with a much more prominent decrease resulting from the lack of distance-dependent scaling, and therefore here the net result would be a moderate decrease of mEPSC amplitude compared to the control level (Fig. 5A).

The spatially flexible adjustment of synaptic efficacy by Kv4.2-dependent bAPs, and the dynamically adjustable excitability by tonic and phasic inhibition together suggest the concerted interplay of complex homeostatic cellular machineries to keep a neuron operating in a normal working range even in extreme situations, for example a complete genetic elimination of one of the key regulators. Our results thus suggest extreme caution when interpreting a phenotype from the genetic manipulation of a single ion channel. Another genetic manipulation, the depletion of GluR1 AMPA subunits, where the putative executive mechanism of scaling (namely the GluR1 subunit-containing AMPA receptor delivery) is missing, also resulted in a dramatic impairment of distance-dependent synaptic scaling (Fig. 5B) with a similar change of steepness of scaling (Andrasfalvy et al. 2003). Moreover, similar changes have been reported in the pathophysiological condition of temporal lobe epilepsy (Bernard et al. 2001, 2004; Cossart et al. 2001; Bernard & Johnston, 2003; Mody, 2005; Glykys & Mody, 2006; El-Hassar et al. 2007), where Kv4.2 expression, Ih current and tonic and phasic inhibition are all altered at different stages of epilepsy causing excitability alteration with a concomitant change of distance-dependent synaptic scaling (Andrásfalvy & Mody, 2005). To better understand the dynamic regulation of synaptic efficacy, further investigation is needed at the right time-scale of these different forms of synaptic plasticity.

References

- Andrásfalvy BK, Magee JC. Distance-dependent increase in AMPA receptor number in the dendrites of adult hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9151–9159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09151.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrásfalvy BK, Mody I. Altered excitatory synaptic events on the apical dendritic arborization of CA1 pyramidal neurons in pilocarpine-induced epileptic mice. Abstr Soc Neurosci. 2005:728.16. [Google Scholar]

- Andrásfalvy BK, Mody I. Differences between the scaling of miniature IPSCs and EPSCs recorded in the dendrites of CA1 mouse pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2006;576:191–196. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrásfalvy BK, Smith MA, Borchardt T, Sprengel R, Magee JC. Impaired regulation of synaptic strength in hippocampal neurons from GluR1-deficient mice. J Physiol. 2003;552:35–45. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Anderson A, Becker A, Poolos NP, Beck H, Johnston D. Acquired dendritic channelopathy in temporal lobe epilepsy. Science. 2004;305:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1097065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Johnston D. Distance-dependent modifiable threshold for action potential back-propagation in hippocampal dendrites. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1807–1816. doi: 10.1152/jn.00286.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Marsden DP, Wheal HV. Changes in neuronal excitability and synaptic function in a chronic model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2001;103:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin RP, Martin LJ, MacDonald JF, Orser BA. α5GABAA receptors regulate the intrinsic excitability of mouse hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:2244–2254. doi: 10.1152/jn.00482.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley SG, Revilla V, Cull-Candy SG, Wisden W, Farrant M. Adaptive regulation of neuronal excitability by a voltage-independent potassium conductance. Nature. 2001;409:88–92. doi: 10.1038/35051086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yuan LL, Zhao C, Birnbaum SG, Frick A, Jung WE, Schwarz TL, Sweatt JD, Johnston D. Deletion of Kv4.2 gene eliminates dendritic A-type K+ current and enhances induction of long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12143–12151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2667-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossart R, Dinocourt C, Hirsch JC, Merchan-Perez A, De Felipe J, Ben-Ari Y, Esclapez M, Bernard C. Dendritic but not somatic GABAergic inhibition is decreased in experimental epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:52–62. doi: 10.1038/82900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan Y, Poo MM. Spike timing-dependent plasticity of neural circuits (Review) Neuron. 2004;44:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debarbieux F, Brunton J, Charpak S. Effect of bicuculline on thalamic activity: a direct blockade of IAHP in reticularis neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2911–2918. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Cudmore RH, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Critical periods for experience-dependent synaptic scaling in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:783–789. doi: 10.1038/nn878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Turrigiano GG. BDNF regulates the intrinsic excitability of cortical neurons. Learn Mem. 1999;6:284–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hassar L, Milh M, Wendling F, Ferrand N, Esclapez M, Bernard C. Cell domain-dependent changes in the glutamatergic and GABAergic drives during epileptogenesis in the rat CA1 region. J Physiol. 2007;578:193–211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick A, Magee J, Johnston D. LTP is accompanied by an enhanced local excitability of pyramidal neuron dendrites. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:126–135. doi: 10.1038/nn1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick A, Magee J, Koester HJ, Migliore M, Johnston D. Normalization of Ca2+ signals by small oblique dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3243–3250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03243.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini S, Losonczy A, Chen X, Johnston D, Magee JC. Associative pairing enhances action potential back-propagation in radial oblique branches of CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2007;580:787–800. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Mann EO, Mody I. Which GABAA receptor subunits are necessary for tonic inhibition in the hippocampus? J Neurosci. 2008;28:1421–1426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4751-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Mody I. Hippocampal network hyperactivity after selective reduction of tonic inhibition in GABAA receptor α5 subunit-deficient mice. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:2796–2807. doi: 10.1152/jn.01122.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein PA, Elsen FP, Ying SW, Ferguson C, Homanics GE, Harrison NL. Prolongation of hippocampal miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents in mice lacking the GABAA receptor α1 subunit. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:3208–3217. doi: 10.1152/jn.00885.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Jung WE, Marionneau C, Aimond F, Xu H, Yamada KA, Schwarz TL, Demolombe S, Nerbonne JM. Targeted deletion of Kv4.2 eliminates Ito,f and results in electrical and molecular remodeling, with no evidence of ventricular hypertrophy or myocardial dysfunction. Circ Res. 2005;97:1342–1350. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196559.63223.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman KN, Pal SK, Burrone J, Murthy VN. Activity-dependent regulation of inhibitory synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nn1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Johnston D. Downregulation of transient K+ channels in dendrites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons by activation of PKA and PKC. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3521–3528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03521.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Johnston D. Neuromodulation of dendritic action potentials. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:408–411. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Johnston D. K+ channel regulation of signal propagation in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1997;387:869–875. doi: 10.1038/43119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Q, Zhang D, Jarzylo L, Huganir RL, Man HY. Homeostatic regulation of AMPA receptor expression at single hippocampal synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:775–780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706447105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Hoffman DA, Colbert CM, Magee JC. Regulation of back-propagating action potentials in hippocampal neurons (Review) Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:288–292. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Jung SC, Clemens AM, Petralia RS, Hoffman DA. Regulation of dendritic excitability by activity-dependent trafficking of the A-type K+ channel subunit Kv4.2 in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2007;54:933–947. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Wei DS, Hoffman DA. Kv4 potassium channel subunits control action potential repolarization and frequency-dependent broadening in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurones. J Physiol. 2005;569:41–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood A, Dudek SM, Gold JT, Aizenman CD, Bear MF. Common forms of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and neocortex in vitro. Science. 1993;260:1518–1521. doi: 10.1126/science.8502997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler JT, Delmas P, Jovanovic JN, Brown DA, Smart TG, Moss SJ. Constitutive endocytosis of GABAA receptors by an association with the adaptin AP2 complex modulates inhibitory synaptic currents in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7972–7977. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07972.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. Dendritic hyperpolarization-activated currents modify the integrative properties of hippocampal CAI pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7613–7624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07613.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Carruth M. Dendritic voltage-gated ion channels regulate the action potential firing mode of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1895–1901. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.4.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Cook EP. Somatic EPSP amplitude is independent of synapse location in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:895–903. doi: 10.1038/78800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Johnston D. A synaptically controlled, associative signal for Hebbian plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Science. 1997;275:209–213. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Lübke J, Frotscher M, Sakmann B. Regulation of synaptic efficacy by coincidence of postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science. 1997;275:213–215. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliore M, Shepherd GM. Emerging rules for the distributions of active dendritic conductances (Review) Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:362–370. doi: 10.1038/nrn810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I. Aspects of the homeostaic plasticity of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition (Review) J Physiol. 2005;562:37–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne JM, Gerber BR, Norris A, Burkhalter A. Electrical remodelling maintains firing properties in cortical pyramidal neurons lacking KCND2-encoded A-type K+ currents. J Physiol. 2008;586:1565–1579. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan E, Colbert CM. Subthreshold inactivation of Na+ and K+ channels supports activity-dependent enhancement of back-propagating action potentials in hippocampal CA1. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1013–1016. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulter MO, Barker JL, O'Carroll AM, Lolait SJ, Mahan LC. Differential and transient expression of GABAA receptor α-subunit mRNAs in the developing rat CNS. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2888–2900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-02888.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenosil GA, Schneider Gasser EM, Rudolph U, Keist R, Fritschy JM, Vogt KE. Specific subtypes of GABAA receptors mediate phasic and tonic forms of inhibition in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:846–857. doi: 10.1152/jn.01199.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers GM, Storm JF. A postsynaptic transient K+ current modulated by arachidonic acid regulates synaptic integration and threshold for LTP induction in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10144–10149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152620399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba RS, Michels G, Jacob TC, Pangalos MN, Moss SJ. Activity-dependent ubiquitination of GABAA receptors regulates their accumulation at synaptic sites. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13341–13351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3277-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Ellis-Davies GCR, Magee JC. Mechanism of the distance-dependent scaling of Schaffer collateral synapses in rat CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2003;548:245–258. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Wall NR, Aakalu GN, Schuman EM. Regulation of dendritic protein synthesis by miniature synaptic events. Science. 2004;304:1979–1983. doi: 10.1126/science.1096202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature. 1998;391:892–896. doi: 10.1038/36103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Welie I, van Hooft JA, Wadman WJ. Homeostatic scaling of neuronal excitability by synaptic modulation of somatic hyperpolarization-activated Ih channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5123–5128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307711101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]