Abstract

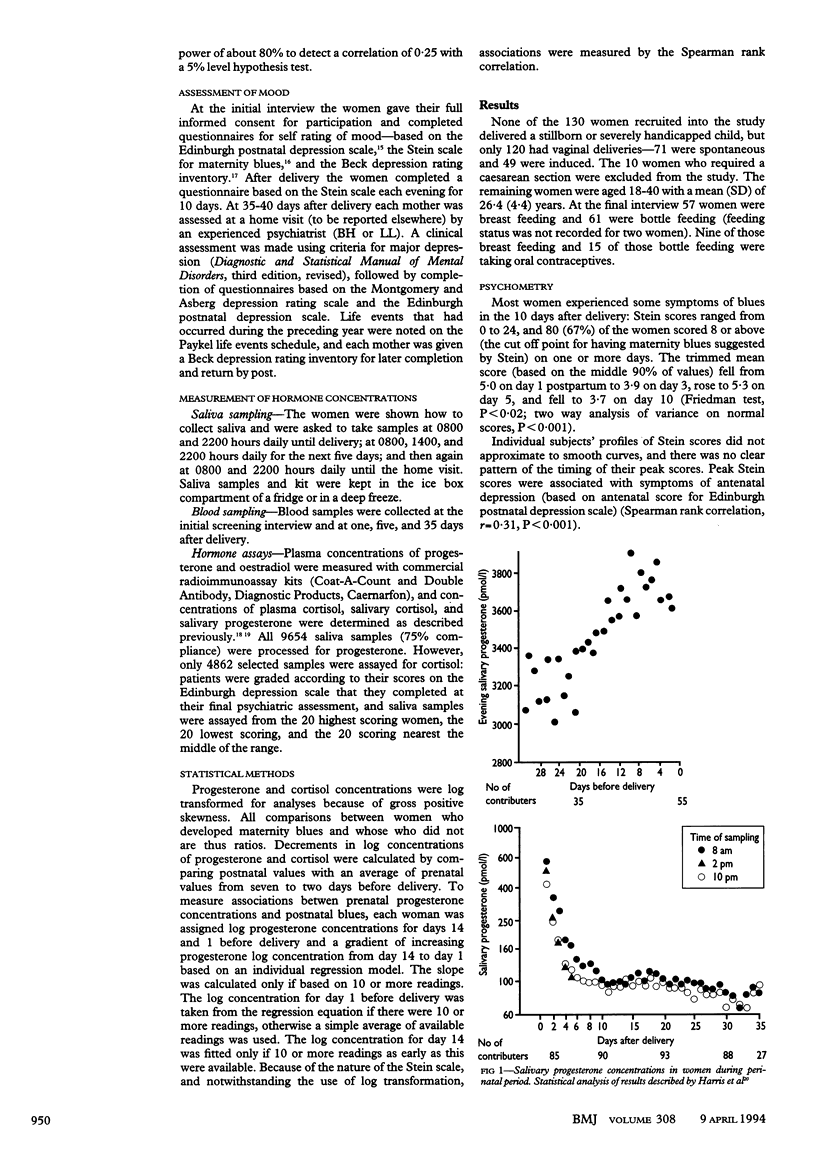

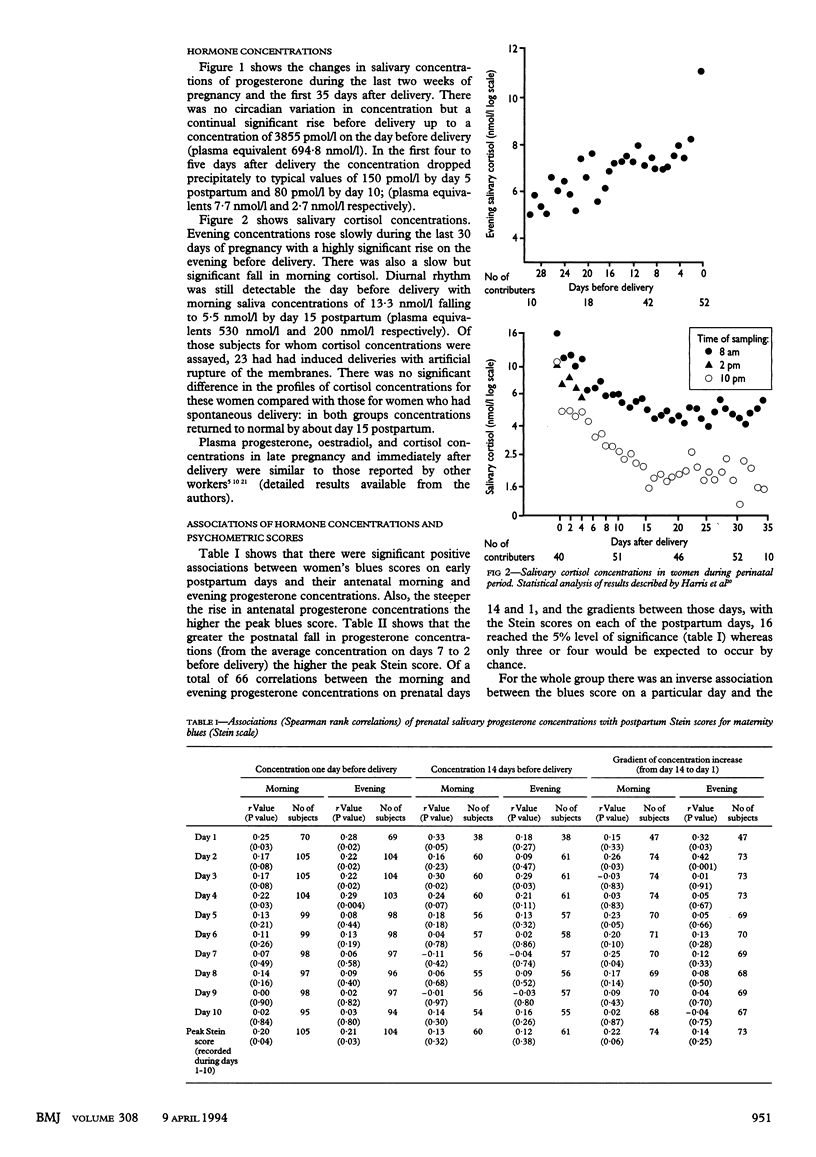

OBJECTIVES--To define relation between mood and concentrations of progesterone and cortisol during perinatal period to test hypothesis that rapid physiological withdrawal of steroid hormones after delivery is associated with depression. DESIGN--Prospective study of primiparous women from two weeks before expected date of delivery to 35 days postpartum. SETTING--Antenatal clinic in university hospital, obstetric inpatient unit, patients' homes. SUBJECTS--120 of 156 primiparous women interviewed. Remainder excluded because of major marital, socioeconomic, or medical problems or because caesarean section required. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Concentrations of progesterone and cortisol in saliva samples; women's moods assessed by various scores for depression. RESULTS--Changes in salivary progesterone and cortisol concentrations were similar to those already characterised for plasma. Peak mean score for maternity blues (5.3 on Stein scale) was on day five postpartum (P < 0.02 compared with mean scores on other postpartum days). High postpartum scores for maternity blues were associated with high antenatal progesterone concentrations on day before delivery (P < 0.05), with high rate of rise of antenatal progesterone concentrations (P < 0.05), with decreasing progesterone concentrations from day of delivery to day of peak blues score (P > or = 0.01), and with low progesterone concentrations on day of peak blues score (P < 0.01). Seventy eight women were designated as having maternity blues (peak score > or = 8 on Stein scale) while 39 had no blues. Women with blues had significantly higher antenatal progesterone concentrations and lower postnatal concentrations than women without blues (geometric mean progesterone concentrations: one day before delivery 3860 pmol/l v 3210 pmol/l respectively, P = 0.03; ten days postpartum 88 pmol/l v 114 pmol/l, P = 0.048). Cortisol concentrations were not significantly associated with mood. CONCLUSION--Maternal mood in the days immediately after delivery is related to withdrawal of naturally occurring progesterone.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson P. J., Hancock K. W., Oakey R. E. Non-protein-bound oestradiol and progesterone in human peripheral plasma before labour and delivery. J Endocrinol. 1985 Jan;104(1):7–15. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1040007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafat E. S., Hargrove J. T., Maxson W. S., Desiderio D. M., Wentz A. C., Andersen R. N. Sedative and hypnotic effects of oral administration of micronized progesterone may be mediated through its metabolites. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Nov;159(5):1203–1209. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECK A. T., WARD C. H., MENDELSON M., MOCK J., ERBAUGH J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961 Jun;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström T., Carstensen H., Södergard R. Concentration of estradiol, testosterone and progesterone in cerebrospinal fluid compared to plasma unbound and total concentrations. J Steroid Biochem. 1976 Jun-Jul;7(6-7):469–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(76)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook N., Harris B., Walker R., Hailwood R., Jones E., Johns S., Riad-Fahmy D. Clinical utility of the dexamethasone suppression test assessed by plasma and salivary cortisol determinations. Psychiatry Res. 1986 Jun;18(2):143–150. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. L., Connor Y., Kendell R. E. Prospective study of the psychiatric disorders of childbirth. Br J Psychiatry. 1982 Feb;140:111–117. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyermek L., Soyka L. F. Steroid anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 1975 Mar;42(3):331–344. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197503000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley S. L., Dunn T. L., Waldron G., Baker J. M. Tryptophan, cortisol and puerperal mood. Br J Psychiatry. 1980 May;136:498–508. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.5.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B., Lovett L., Roberts S., Read G. F., Riad-Fahmy D. Cardiff puerperal mood and hormone study. 1. Saliva steroid hormone profiles in late pregnancy and the puerperium: endocrine factors and parturition. Horm Res. 1993;39(3-4):138–145. doi: 10.1159/000182714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B., Watkins S., Cook N., Walker R. F., Read G. F., Riad-Fahmy D. Comparisons of plasma and salivary cortisol determinations for the diagnostic efficacy of the dexamethasone suppression test. Biol Psychiatry. 1990 Apr 15;27(8):897–904. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90471-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendell R. E., McGuire R. J., Connor Y., Cox J. L. Mood changes in the first three weeks after childbirth. J Affect Disord. 1981 Dec;3(4):317–326. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(81)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz A., Stump K., Cowen P. J., Elliott J. M., Gelder M. G., Grahame-Smith D. G. Changes in platelet alpha 2-adrenoceptor binding post partum: possible relation to maternity blues. Lancet. 1983 Mar 5;1(8323):495–498. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monheit A. G., Cousins L., Resnik R. The puerperium: anatomic and physiologic readjustments. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Dec;23(4):973–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott P. N., Franklin M., Armitage C., Gelder M. G. Hormonal changes and mood in the puerperium. Br J Psychiatry. 1976 Apr;128:379–383. doi: 10.1192/bjp.128.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara M. W., Schlechte J. A., Lewis D. A., Wright E. J. Prospective study of postpartum blues. Biologic and psychosocial factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991 Sep;48(9):801–806. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt B. 'Maternity blues'. Br J Psychiatry. 1973 Apr;122(569):431–433. doi: 10.1192/bjp.122.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riad-Fahmy D., Read G. F., Walker R. F., Walker S. M., Griffiths K. Determination of ovarian steroid hormone levels in saliva. An overview. J Reprod Med. 1987 Apr;32(4):254–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein G., Marsh A., Morton J. Mental symptoms, weight changes, and electrolyte excretion in the first post partum week. J Psychosom Res. 1981;25(5):395–408. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(81)90054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway C. R., Kane F. J., Jr, Jarrahi-Zadeh A., Lipton M. A. A psychoendocrine study of pregnancy and puerperium. Am J Psychiatry. 1969 Apr;125(10):1380–1386. doi: 10.1176/ajp.125.10.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. F., Read G. F., Riad-Fahmy D. Radioimmunoassay of progesterone in saliva: application to the assessment of ovarian function. Clin Chem. 1979 Dec;25(12):2030–2033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]