Abstract

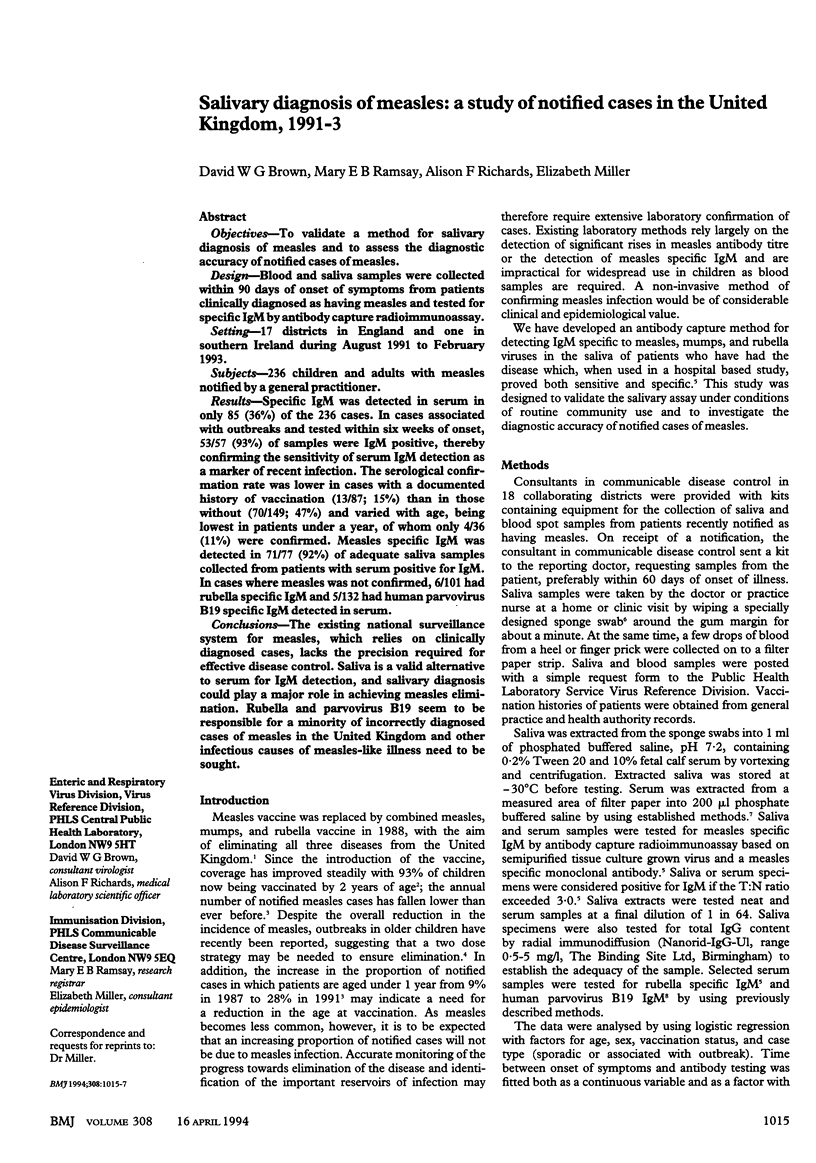

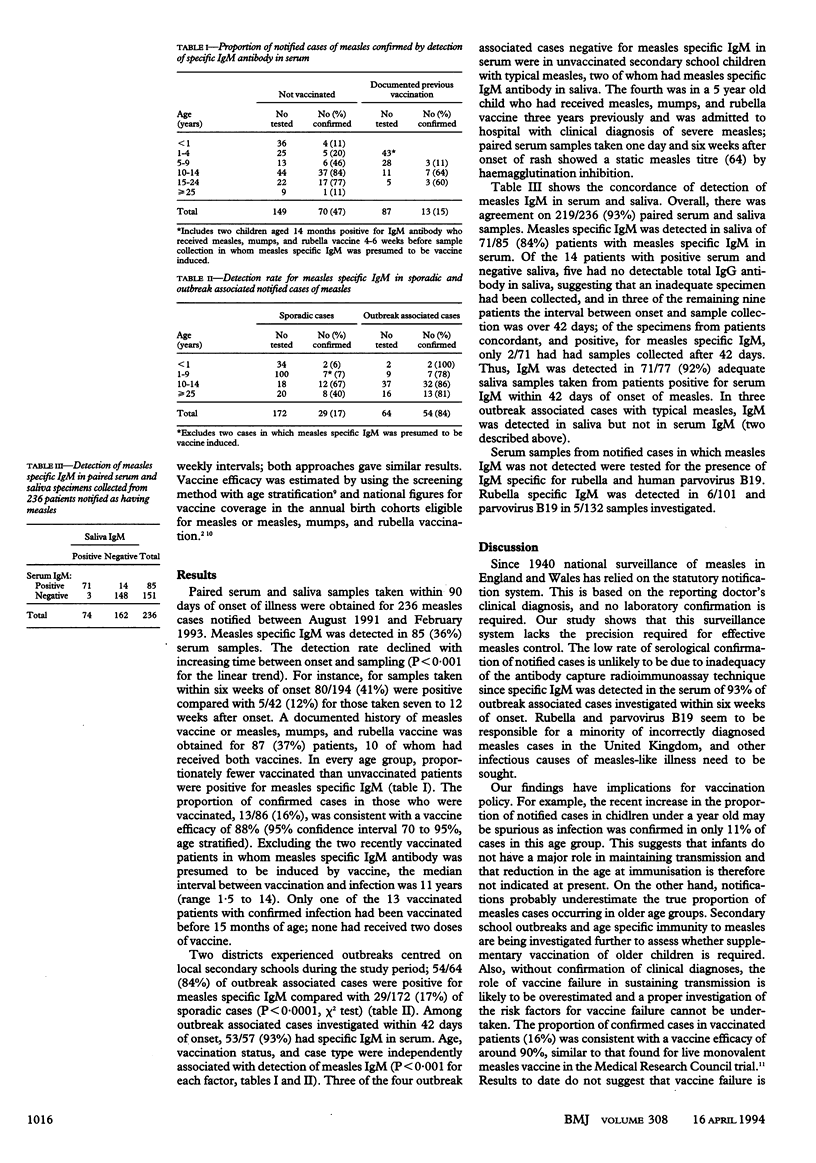

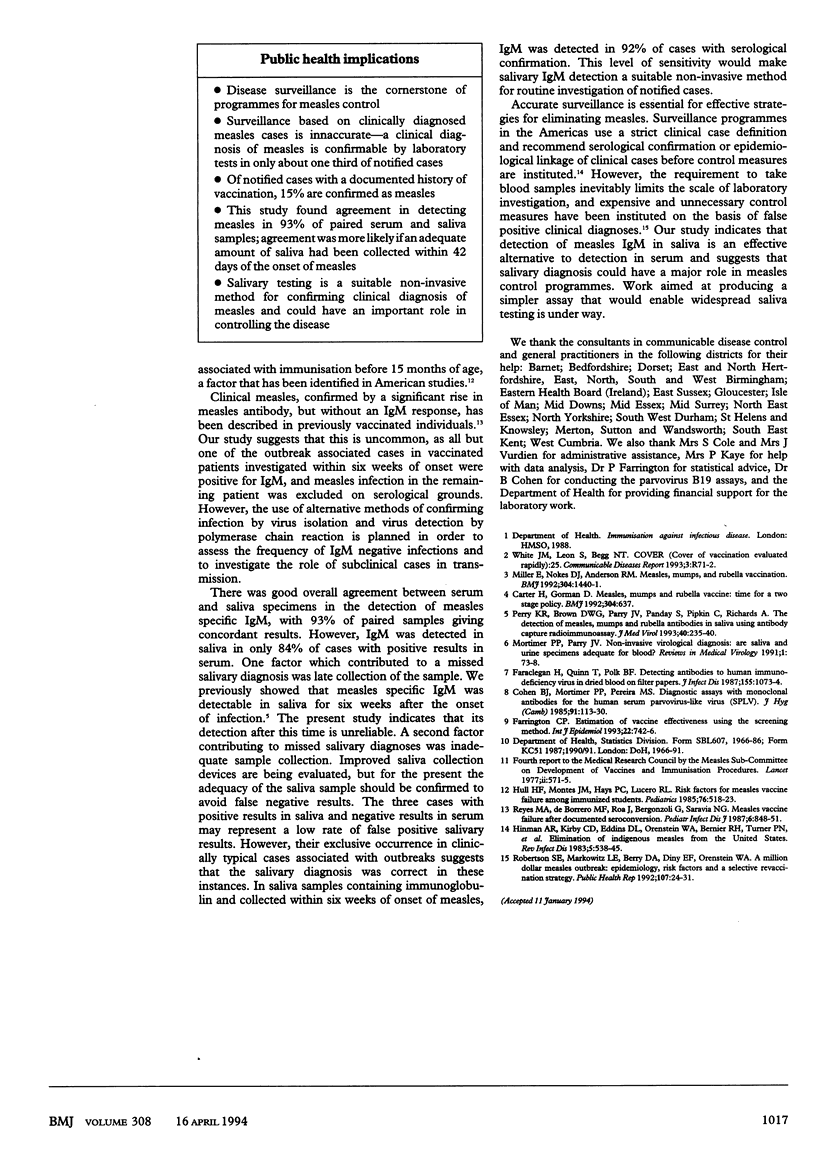

OBJECTIVES--To validate a method for salivary diagnosis of measles and to assess the diagnostic accuracy of notified cases of measles. DESIGN--Blood and saliva samples were collected within 90 days of onset of symptoms from patients clinically diagnosed as having measles and tested for specific IgM by antibody capture radioimmunoassay. SETTING--17 districts in England and one in southern Ireland during August 1991 to February 1993. SUBJECTS--236 children and adults with measles notified by a general practitioner. RESULTS--Specific IgM was detected in serum in only 85 (36%) of the 236 cases. In cases associated with outbreaks and tested within six weeks of onset, 53/57 (93%) of samples were IgM positive, thereby confirming the sensitivity of serum IgM detection as a marker of recent infection. The serological confirmation rate was lower in cases with a documented history of vaccination (13/87; 15%) than in those without (70/149; 47%) and varied with age, being lowest in patients under a year, of whom only 4/36 (11%) were confirmed. Measles specific IgM was detected in 71/77 (92%) of adequate saliva samples collected from patients with serum positive for IgM. In cases where measles was not confirmed, 6/101 had rubella specific IgM and 5/132 had human parvovirus B19 specific IgM detected in serum. CONCLUSIONS--The existing national surveillance system for measles, which relies on clinically diagnosed cases, lacks the precision required for effective disease control. Saliva is a valid alternative to serum for IgM detection, and salivary diagnosis could play a major role in achieving measles elimination. Rubella and parvovirus B19 seem to be responsible for a minority of incorrectly diagnosed cases of measles in the United Kingdom and other infectious causes of measles-like illness need to be sought.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Carter H., Gorman D. Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine: time for a two stage policy? BMJ. 1992 Mar 7;304(6827):637–637. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6827.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B. J., Mortimer P. P., Pereira M. S. Diagnostic assays with monoclonal antibodies for the human serum parvovirus-like virus (SPLV). J Hyg (Lond) 1983 Aug;91(1):113–130. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400060095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman A. R., Kirby C. D., Eddins D. L., Orenstein W. A., Bernier R. H., Turner P. M., Bart K. J. Elimination of indigenous measles from the United States. Rev Infect Dis. 1983 May-Jun;5(3):538–545. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.3.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull H. F., Montes J. M., Hays P. C., Lucero R. L. Risk factors for measles vaccine failure among immunized students. Pediatrics. 1985 Oct;76(4):518–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E., Nokes D. J., Anderson R. M. Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination. BMJ. 1992 May 30;304(6839):1440–1441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6839.1440-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes M. A., de Borrero M. F., Roa J., Bergonzoli G., Saravia N. G. Measles vaccine failure after documented seroconversion. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987 Sep;6(9):848–851. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198709000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S. E., Markowitz L. E., Berry D. A., Dini E. F., Orenstein W. A. A million dollar measles outbreak: epidemiology, risk factors, and a selective revaccination strategy. Public Health Rep. 1992 Jan-Feb;107(1):24–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]