Abstract

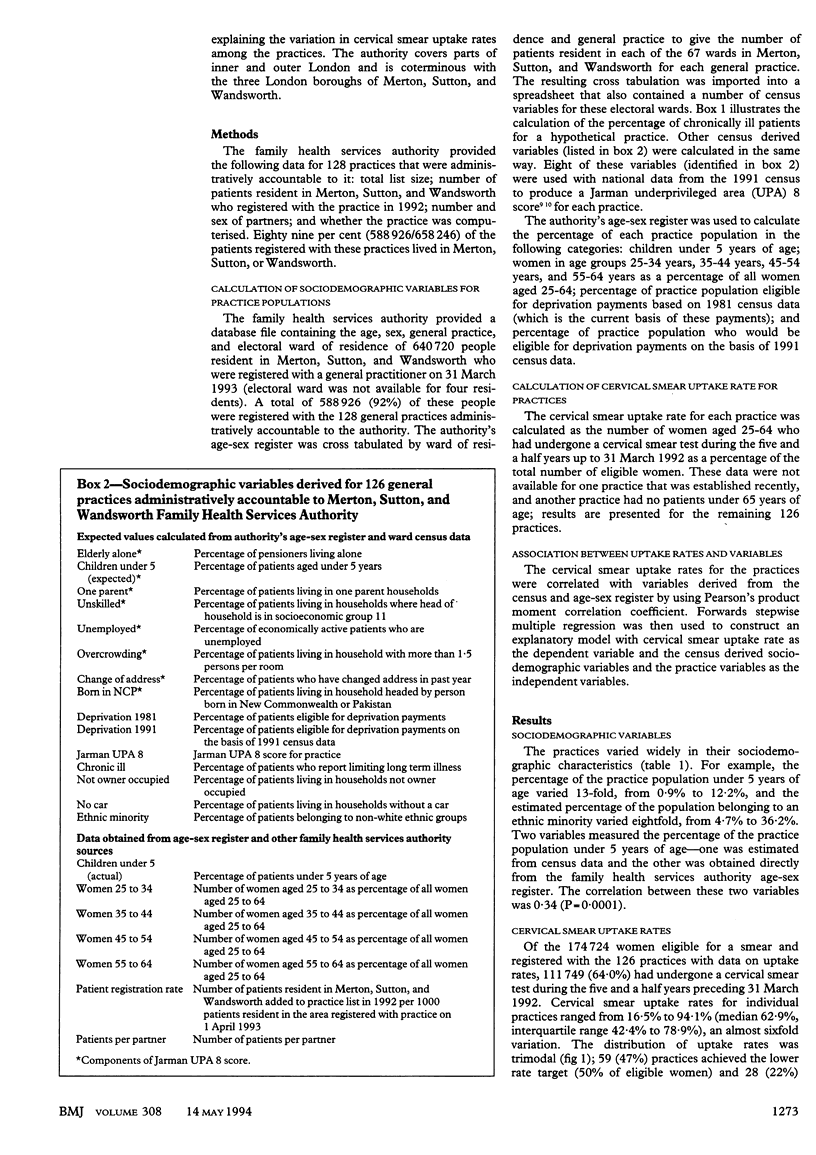

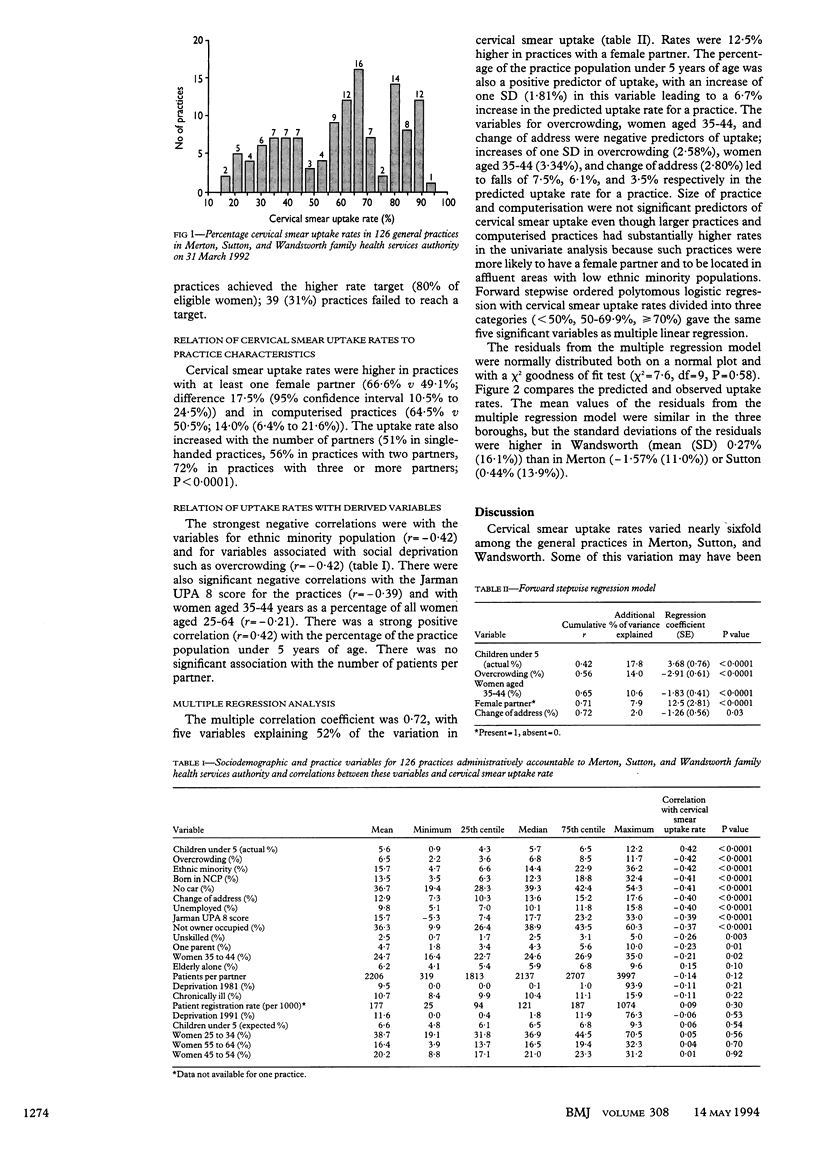

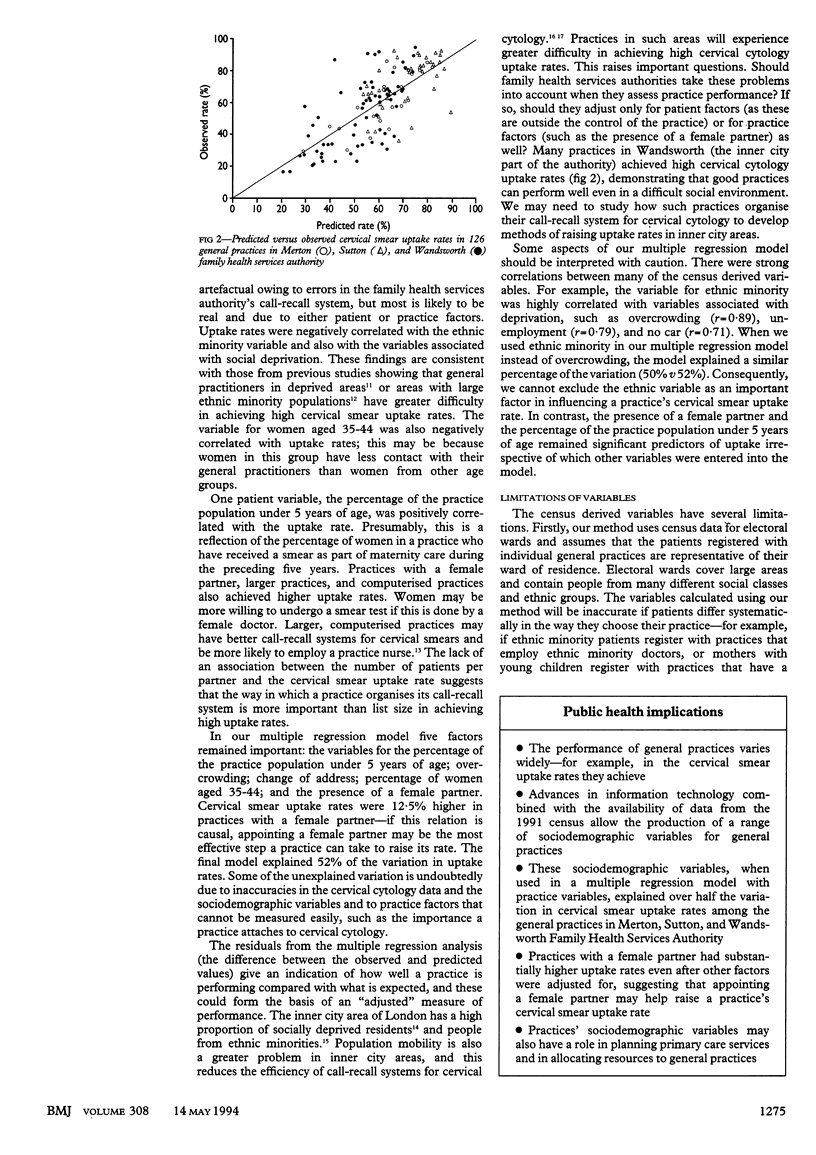

OBJECTIVES--To produce practice and patient variables for general practices from census and family health services authority data, and to determine the importance of these variables in explaining variation in cervical smear uptake rates between practices. DESIGN--Population based study examining variations in cervical smear uptake rates among 126 general practices using routine data. SETTING--Merton, Sutton, and Wandsworth Family Health Services Authority, which covers parts of inner and outer London. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE--Percentage of women aged 25-64 years registered with a general practitioner who had undergone a cervical smear test during the five and a half years preceding 31 March 1992. RESULTS--Cervical smear uptake rates varied from 16.5% to 94.1%. The estimated percentage of practice population from ethnic minority groups correlated negatively with uptake rates (r = -0.42), as did variables associated with social deprivation such as overcrowding (r = -0.42), not owning a car (r = -0.41), and unemployment (r = -0.40). Percentage of practice population under 5 years of age correlated positively with uptake rate (r = 0.42). Rates were higher in practices with a female partner than in those without (66.6% v 49.1%; difference 17.5% (95% confidence interval 10.5% to 24.5%)), and in computerised than in non-computerised practices (64.5% v 50.5%; 14.0% (6.4% to 21.6%)). Rates were higher in larger practices. In a stepwise multiple regression model that explained 52% of variation, five factors were significant predictors of uptake rates: presence of a female partner; children under 5; overcrowding; number of women aged 35-44 as percentage of all women aged 25-64; change of address in past year. CONCLUSIONS--Over half of variation in cervical smear uptake rates can be explained by patient and practice variables derived from census and family health services authority data; these variables may have a role in explaining variations in performance of general practices and in producing adjusted measures of practice performance. Practices with a female partner had substantially higher uptake rates.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Amery J., Beardow R., Oerton J., Victor C. The efficacy of a national Family Health Services Authority based cervical cytology system. Health Trends. 1992;24(4):119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D., Klein R. Explaining outputs of primary health care: population and practice factors. BMJ. 1991 Jul 27;303(6796):225–229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6796.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R. General practice in Gloucestershire, Avon and Somerset: explaining variations in standards. Br J Gen Pract. 1992 Oct;42(363):415–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balarajan R., Yuen P., Machin D. Deprivation and general practitioner workload. BMJ. 1992 Feb 29;304(6826):529–534. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6826.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardow R., Oerton J., Victor C. Evaluation of the cervical cytology screening programme in an inner city health district. BMJ. 1989 Jul 8;299(6691):98–100. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6691.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A., Jacobson B. Screening: the inadequacy of population registers. BMJ. 1989 Mar 4;298(6673):545–546. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6673.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy C., Hutchinson A., Smyth J. Providing census data for general practice. 2. Usefulness. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1987 Oct;37(303):451–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam S. J. Provision of health promotion clinics in relation to population need: another example of the inverse care law? Br J Gen Pract. 1992 Feb;42(355):54–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson A., Foy C., Smyth J. Providing census data for general practice. 1. Feasibility. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1987 Oct;37(303):448–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson B. Public health in inner London. BMJ. 1992 Nov 28;305(6865):1344–1347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6865.1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman B. Identification of underprivileged areas. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983 May 28;286(6379):1705–1709. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6379.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman B. Underprivileged areas: validation and distribution of scores. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Dec 8;289(6458):1587–1592. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6458.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M., Coulter A., Jones L. A total audit of preventive procedures in 45 practices caring for 430,000 patients. BMJ. 1990 Jun 9;300(6738):1501–1503. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6738.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leese B., Bosanquet N. High and low incomes in general practice. BMJ. 1989 Apr 8;298(6678):932–934. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6678.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff K. J., Corrigan A. M., Bosher M., Edmonds M. P., Sacks D., Coleman D. V. Cervical screening in an inner city area: response to a call system in general practice. BMJ. 1988 Nov 19;297(6659):1317–1318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6659.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usherwood T. P., Kapasi M. A., Barber J. H. Wide variations in the night visiting rate. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1985 Aug;35(277):395–395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]