Abstract

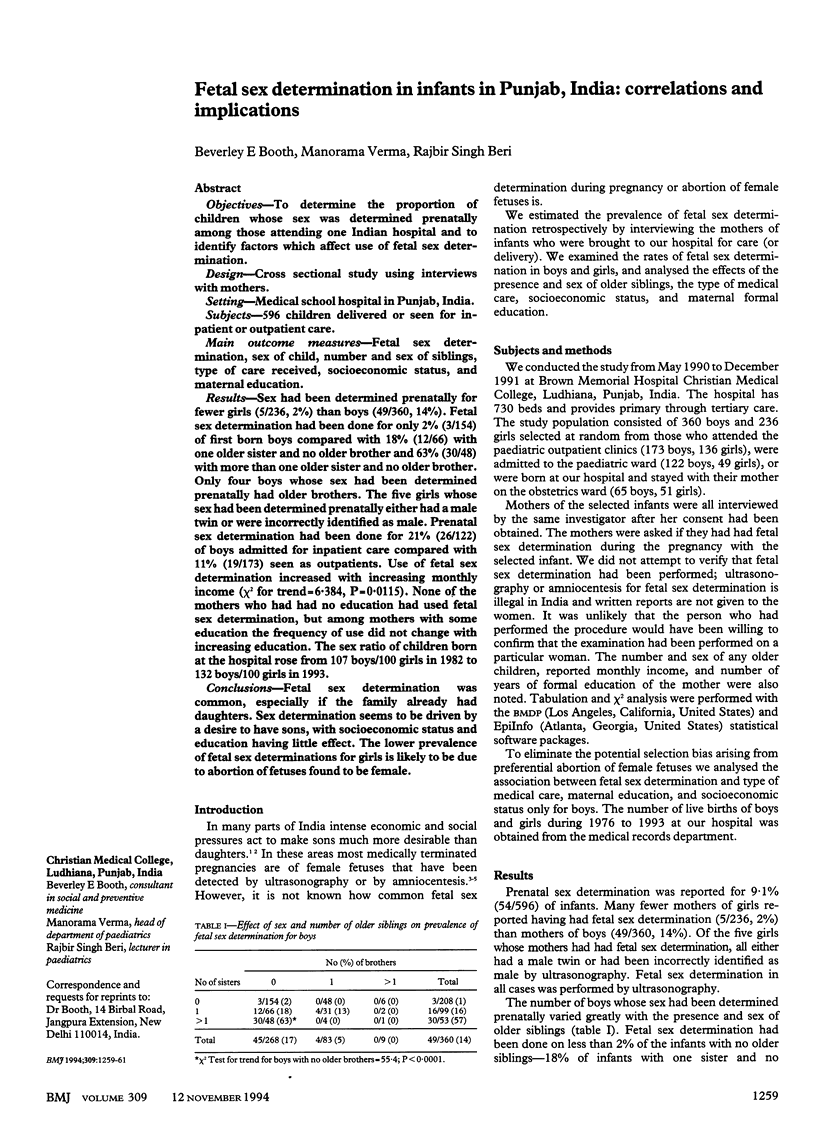

OBJECTIVES--To determine the proportion of children whose sex was determined prenatally among those attending one Indian hospital and to identify factors which affect use of fetal sex determination. DESIGN--Cross sectional study using interviews with mothers. SETTING--Medical school hospital in Punjab, India. SUBJECTS--596 children delivered or seen for inpatient or outpatient care. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Fetal sex determination, sex of child, number and sex of siblings, type of care received, socioeconomic status, and maternal education. RESULTS--Sex had been determined prenatally for fewer girls (5/236, 2%) than boys (49/360, 14%). Fetal sex determination had been done for only 2% (3/154) of first born boys compared with 18% (12/66) with one older sister and no older brother and 63% (30/48) with more than one older sister and no older brother. Only four boys whose sex had been determined prenatally had older brothers. The five girls whose sex had been determined prenatally either had a male twin or were incorrectly identified as male. Prenatal sex determination had been done for 21% (26/122) of boys admitted for inpatient care compared with 11% (19/173) seen as outpatients. Use of fetal sex determination increased with increasing monthly income (chi2 for trend = 6.384, P = 0.0115). None of the mothers who had had no education had used fetal sex determination, but among mothers with some education the frequency of use did not change with increasing education. The sex ratio of children born at the hospital rose from 107 boys/100 girls in 1982 to 132 boys/100 girls in 1993. CONCLUSIONS--Fetal sex determination was common, especially if the family already had daughters. Sex determination seems to be driven by a desire to have sons, with socioeconomic status and education having little effect. The lower prevalence of fetal sex determinations for girls is likely to be due to abortion of fetuses found to be female.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Booth B. E., Verma M. Decreased access to medical care for girls in Punjab, India: the roles of age, religion, and distance. Am J Public Health. 1992 Aug;82(8):1155–1157. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.8.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla T. The plight of female infants in India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1980 Jun;34(2):143–146. doi: 10.1136/jech.34.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plattner G., Renner W., Went J., Beaudette L., Viau G. Fetal sex determination by ultrasound scan in the second and third trimesters. Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Apr;61(4):454–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanamma A., Bambawale U. The mania for sons: an analysis of social values in South Asia. Soc Sci Med Med Anthropol. 1980 May;14(2):107–110. doi: 10.1016/0160-7987(80)90059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao R. India: move to stop sex-test abortion. Nature. 1986 Nov 20;324(6094):202–202. doi: 10.1038/324202b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece E. A., Winn H. N., Wan M., Burdine C., Green J., Hobbins J. C. Can ultrasonography replace amniocentesis in fetal gender determination during the early second trimester? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Mar;156(3):579–581. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter S. D. Sex predetermination and epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 1975 Feb;9(2):105–110. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(75)90102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]