Abstract

Background

It has been suggested that chromosomal rearrangements harbor the molecular footprint of the biological phenomena which they induce, in the form, for instance, of changes in the sequence divergence rates of linked genes. So far, all the studies of these potential associations have focused on the relationship between structural changes and the rates of evolution of single-copy DNA and have tried to exclude segmental duplications (SDs). This is paradoxical, since SDs are one of the primary forces driving the evolution of structure and function in our genomes and have been linked not only with novel genes acquiring new functions, but also with overall higher DNA sequence divergence and major chromosomal rearrangements.

Results

Here we take the opposite view and focus on SDs. We analyze several of the features of SDs, including the rates of intraspecific divergence between paralogous copies of human SDs and of interspecific divergence between human SDs and chimpanzee DNA. We study how divergence measures relate to chromosomal rearrangements, while considering other factors that affect evolutionary rates in single copy DNA.

Conclusion

We find that interspecific SD divergence behaves similarly to divergence of single-copy DNA. In contrast, old and recent paralogous copies of SDs do present different patterns of intraspecific divergence. Also, we show that some relatively recent SDs accumulate in regions that carry inversions in sister lineages.

Background

Initial analyses of the human genome sequence have showed that ~5% of the human genome is composed by interspersed segmental duplications (SDs) [1]. SDs can be defined as blocks of DNA ranging from 1–400 kb in length, with copies found in multiple sites and that typically share high sequence similarity (> 90%). The distribution of these duplications is non-uniform within and among chromosomes, with a tendency to cluster in pericentromeric and subtelomeric regions [2-7] and in the breakpoints of chromosomal rearrangements [8-12]

Duplications have both functional and structural effects [1,2,6,7,9,13-15]. Their functional consequences are very diverse. First, by predisposing chromosomal architectures to be rearranged by non-allelic homologous recombination [7,12,16-18], SDs constitute genetic risk factors for many diseases (e.g. Prader-Willi, Williams-Beuren Syndromes, juvenile nephronophtisis or spinal muscular atrophy). Second, SDs are related to genic evolution because they produce duplications of coding sequences that can lead to genes with new functions [7,19-25]. Finally, rates of evolution of duplicated genes are accelerated just after the duplication event [26]. These accelerations could be due to an increase of mutation rates after duplication, the relaxation of purifying selection due to the duplication of functional genes, the action of positive diversifying selection on one or both copies, or a combination of these factors [5,25-28].

Regarding structural effects, SDs predispose chromosomes to rearrangements, which suggests that SDs may be the main force driving the evolution of genomic structure along the lineages of mammalian species [8-12]. Other studies, however, point to both SDs and chromosomal rearrangements as different manifestations of the intrinsic instability of some particular DNA sequences [9,13,29,30].

Recently, interest in the role of chromosomal rearrangements in speciation processes has been renewed. Models of chromosomal speciation based on the reduction of recombination induced by rearrangements pose that regions involved in those rearrangements could become isolated earlier when compared to the rest of the genome [31-34]. These models predict an association between rearranged regions involved in any speciation process and higher divergence rates of linked DNA sequences. Current evidence for or against such models is extremely contradictory. In human-chimpanzee comparisons, higher evolutionary rates were originally linked to chromosomal rearrangements [35-37], whereas other studies found no effect [38,39] and even more recent ones have detected lower evolutionary rates within inversions [40]. In other lineages, new studies remain consistent with the original finding of higher evolutionary rates associated with chromosomal rearrangements [41-43].

Other explanations have been proposed to account for the relationship between chromosomal rearrangements and faster or slower evolutionary rates. For example, chromosomal rearrangements can influence DNA divergence rates simply by inducing changes in genomic contexts. For instance, if some DNA fragments are moved by a chromosomal inversion from a region with different recombination rates or different equilibrium nucleotide composition, this could induce changes in mutation [44,45]. Also, rearrangements may tend to occur or to be fixed in regions of relaxed purifying selection and, thus, of faster genic evolution [5,36]. Finally, chromosomal rearrangements (especially chromosomal fissions) have been found to be located in regions of ancestrally high GC content in mammals (at least in the Dog genome) [46]. Thus, ancestral GC content could be contributing to the observed relationship between chromosomal rearrangements and higher mutation rates by means of methylation and deamination of CpG dinucleotides, leading to higher divergence measures in regions close (and within) the rearrangements.

Regardless of how the relationship between sequence evolution and chromosomal location change is ultimately resolved, it is important to consider the possibility of an association between SDs and chromosomal rearrangements in relation to speciation. If rearranged chromosomes, whose breakpoints are enriched with SDs, take part in speciation processes in which individuals bearing different chromosomal structures become genetically isolated, it is possible that evolutionary novelties contained in these duplications play some role in such isolation processes.

To tackle this issue we must start by understanding the rates and patterns of SD divergence in the primate lineages. Here, we analyze the genomic distribution of intraspecific divergence between paralogous copies of human SDs and of interspecific divergence between regions duplicated either in humans or chimpanzees and their homologous sequences in the other species. We take into account all major chromosomal rearrangements (see Methods), and, in addition, several other genomic variables that affect evolutionary rates of single copy DNA, such as, linkage to the X chromosome, HSAX [41,47,48], or to telomeric and centromeric regions [40,49-51].

Results

We addressed three main sets of questions. First, how are SDs distributed in the genome relative to rearrangements? Second, what is the genomic distribution of divergence between paralogous copies of human SDs, especially in relation to rearrangements? And, third, what are the divergence distribution patterns of copies of SDs between humans and chimpanzees? To address each of these questions we used three different datasets (see Material & Methods for a detailed description). The first one (Raw dataset) contains pairs of coordinates of fragments of the human genome that have been defined as segmental duplications [1] together with measures of divergence between these paralogous fragments. This dataset is used to detect accumulations of SDs in different parts of the genome. The second dataset (Non-overlapping intraspecific dataset) was created to remove redundant information from the previous dataset. It contains only a sample of SDs representative of each duplicated region. Finally, a third dataset (Non-overlapping interspecific dataset) was designed to represent the inter-specific divergence between human and chimpanzee for non-overlapping duplicated regions of the human genome. The aim of the two Non-overlapping datasets is to study the distribution of SD divergence rates in different regions of the genome while avoiding the redundant information that the first dataset contains. To do so, the simplifying assumption is made that the selected representative of each duplicated region actually reflects the complex history of the region.

Overrepresentation of relatively young SDs in rearranged regions

We started using the raw dataset (Dataset 1, see Methods) to study the distribution of paralogous copies of human SDs relative to the nine major rearrangements (Inversions) between humans and chimpanzees (human chromosomes 4, 5, 9, 12, 15, 16, 17 and 18). We defined as "young" SDs those with a greater than 98% sequence identity among copies, while SDs with less than 92% identity were labeled as "old". These labels, of course, do not imply strict age estimates, since gene conversion or positive selection are known to influence divergence rates of SDs.

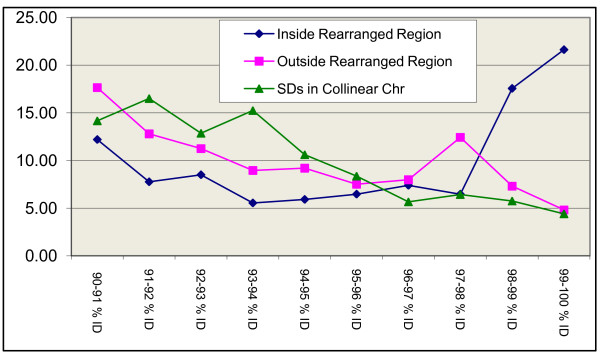

After all the filtering processes (see Methods) in the filtered dataset, we observed a higher proportion of young SDs within rearranged regions than outside them: ~40% of SDs located within rearranged regions are young, while this figure is only ~12% for SDs outside the inverted regions of the same chromosomes. Also, these regions contained younger SDs than colinear chromosomes, where only ~11% of SDs are classified as young (Table 1, Figure 1). It is crucial to note that these young duplications cannot be caused by the inversions. Most of the 10 major rearrangements separating humans and chimpanzees took place in the chimpanzee lineage [52], and here we are analyzing human SDs. Thus, this association is not caused by an accumulation of SDs within the inversion itself, but within the orthologous region in the homologous chromosome of the sister species, which retained the ancestral structure.

Table 1.

Distribution of SD identities relative to major genomic rearrangements between humans and chimpanzees.

| Inside rearranged regions | Outside rearranged regions | Colinear Chromosome | |

| Similarity(ID) | Percentage of age within each cathegory (%) | ||

| 90–91% ID | 12.20 | 17.64 | 14.16 |

| 91–92% ID | 7.76 | 12.79 | 16.50 |

| 92–93% ID | 8.50 | 11.25 | 12.86 |

| 93–94% ID | 5.55 | 8.96 | 15.24 |

| 94–95% ID | 5.91 | 9.19 | 10.61 |

| 95–96% ID | 6.47 | 7.51 | 8.36 |

| 96–97% ID | 7.39 | 7.98 | 5.67 |

| 97–98% ID | 6.47 | 12.42 | 6.43 |

| 98–99% ID | 17.56 | 7.31 | 5.76 |

| 99–100% ID | 21.63 | 4.81 | 4.41 |

The percentages were calculated as the proportion of pairwise alignments at each percent identity.

Figure 1.

Distribution of SDs identities relative to major rearrangements (Inversions) between humans and chimpanzees. In Blue, the distribution of percentages of SDs that are located within the inversion of human chromosomes rearranged relative to chimpanzees. In pink, the distribution of SDs in rearranged chromosomes but outside the rearrangements. In green the percentages of identities of SDs located in chromosomes that are collinear (not rearranged) for both species.

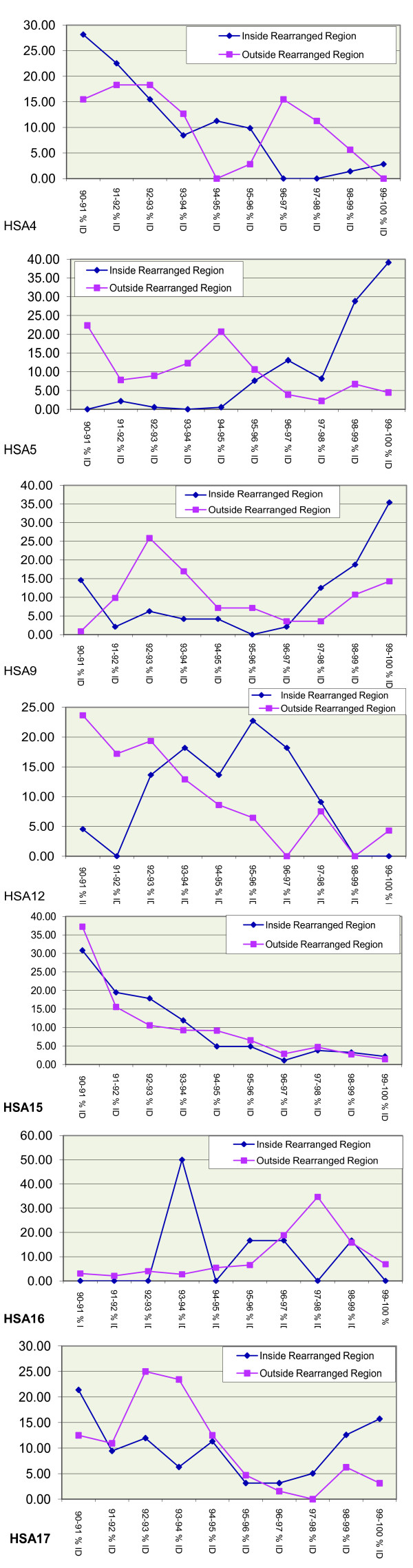

To check whether these results were due to a genome-wide phenomenon or were driven by some individual chromosomes, we performed a chromosome by chromosome analysis. This allowed us to pinpoint HSA5 and HSA9 as primarily responsible for the reported association. These chromosomes show the largest difference in percent identity and correspond to the greatest proportion of alignments (total number of SD pairs). No other chromosome showed a differential accumulation of young SDs within their rearrangements (Figure 2). Therefore, the association above is mainly due to these two chromosomes which, being inverted in one lineage (chimpanzee), have accumulated an expansion of recent SDs in its sister lineage (human).

Figure 2.

Distribution of identities relative to major rearrangements between human and chimpanzees for individual chromosomes. Chromosomes without any pair of copies of SDs within rearrangements are not shown (see Methods).

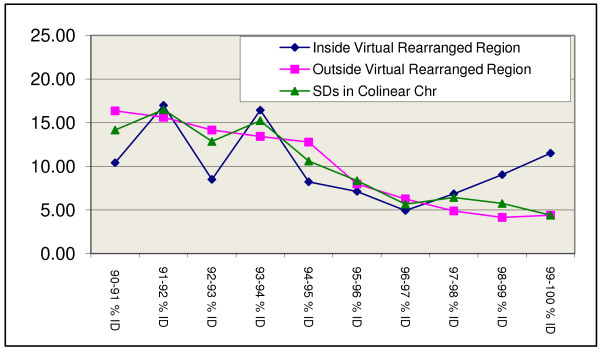

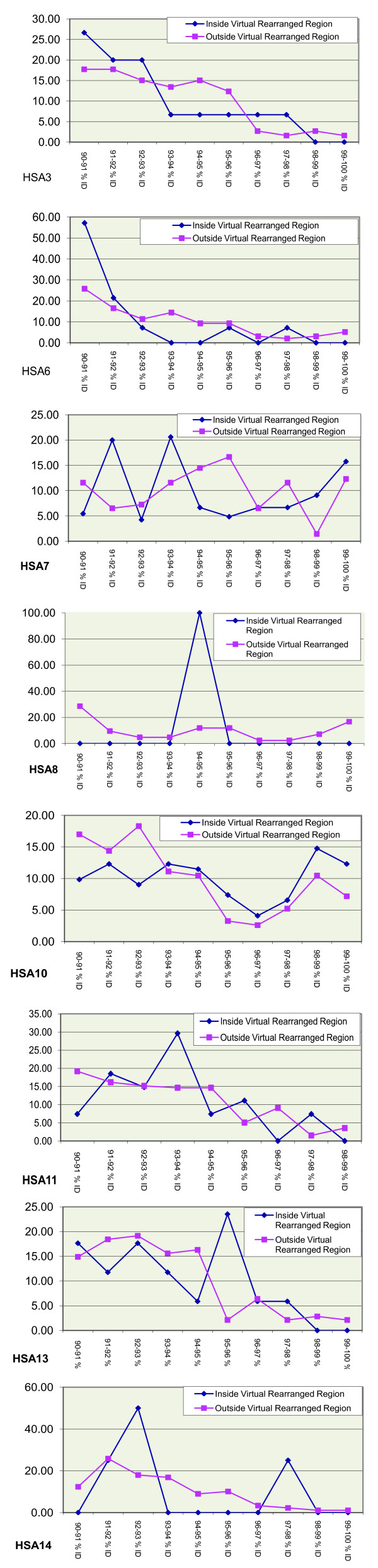

Given that SDs tend to cluster within pericentromeric and subtelomeric zones [1,5,50], part of the above effect could be attributed to the fact that all the major rearrangements between humans and chimpanzees are pericentric, and thus include the centromere. We accounted for this possibility by excluding SDs that mapped within 5 Mb of the centromeres. To make sure that the filtering process had eliminated any centromere-associated effect, we simulated pericentric inversions in colinear chromosomes and searched for young SDs within them. Pseudo-inverted pericentric regions in colinear chromosomes were defined as regions equivalent in length and location to real rearrangements. Given that the average inversion spans 24.98% of its chromosome, we created a virtual inversion of that size in each colinear chromosome, keeping the centromere as the center of the inversion. On average, chromosomes with virtual inversions did present a higher proportion of young SDs, but the effect is not as large. First, the increase was only 50% of that in real inversions (Table 2, Figure 3); and second, only HSA10 and HSA7 seemed to accumulate some local clustering of recent SDs (Figure 4). However, clustering is not exclusive of the inverted region, as is the case for the inverted chromosomes HSA5 and HSA9, but extends all over the chromosome. The rest of the colinear chromosomes did not show any particular age distribution of SDs inside vs. outside virtual rearrangements, suggesting that the association of young SDs and rearranged chromosomes 5 and 9 might be not only due to the accumulation of SDs near centromeres, even if that accumulation is likely to make a major contribution to the magnitude of our observation.

Table 2.

Distribution of SDs identities relative to simulated rearrangements in colinear chromosomes between human and chimpanzees.

| Inside rearranged regions | Outside rearranged regions | |

| Similarity(ID) | Percentage of age within each category (%) | |

| 90–91% ID | 10.41 | 16.35 |

| 91–92% ID | 16.99 | 15.62 |

| 92–93% ID | 8.49 | 14.16 |

| 93–94% ID | 16.44 | 13.43 |

| 94–95% ID | 8.22 | 12.77 |

| 95–96% ID | 7.12 | 7.97 |

| 96–97% ID | 4.93 | 6.27 |

| 97–98% ID | 6.85 | 4.88 |

| 98–99% ID | 9.04 | 4.15 |

| 99–100% ID | 11.51 | 4.39 |

The percentages were calculated as the proportion of pairwise alignments at each percent identity.

Figure 3.

Distribution of SDs identities relative to simulated pericentromeric rearrangements in colinear chromosomes between humans and chimpanzees.

Figure 4.

Distribution of SDs identities relative to simulated pericentric rearrangements in colinear chromosomes between humans and chimpanzees for individual chromosome. Chromosomes without any pair of copies of SDs within simulated rearrangements are not shown (see Methods).

The distribution of divergence between human paralogous SDs

To study how the rates of intraspecific evolution of SD may be affected by rearrangements and other factors such as the location in sex chromosomes or telomeres, we used a second dataset: the non-overlapping dataset or Dataset 2 (see Methods). Given the results above, we extracted two subsets from the original dataset: "young SDs" (> 98% ID) and "old SDs" (< 92% ID). We kept, as representatives of every covered zone, SDs that had both copies in the same class of region (see Additional file 1).

We sequentially analyzed and removed every known variable affecting divergence rates (Table 3), starting with sex chromosomes. Young human SDs located in HSAX presented less divergence among copies than equivalent SDs in autosomes. This is not the case for old SDs. No length differences were detected in SDs located in HSAX. When located in HSAY, young SDs presented lower intra-specific divergence and increased length. Old SDs in HSAY are also longer, but, in contrast, they present higher divergence between paralogous copies.

Table 3.

Average of divergences and lengths among paralogous copies of SDs relative to genomic factors and rearrangements between human and chimpanzees.

| Sex Chromosomes | ID | |||

| SDs in Autosomes | SDs in HSAX | P-value | > 98% | |

| N | 889 | 103 | ||

| K | 0.0107 | 0.0076 | < 0.001 | |

| Size | 41,439.50 | 52,887.93 | 0.115 | |

| SDs in Autosomes | SDs in HSAX | P-value | < 92% | |

| N | 3273 | 261 | ||

| K | 0.0958 | 0.0962 | 0.364 | |

| Size | 4,689.73 | 4,458.48 | 0.578 | |

| SDs in Autosomes | SDs in HSAY | P value | > 98% | |

| N | 889 | 32 | ||

| K | 0.0107 | 0.0052 | < 0.001 | |

| Size | 41,439.50 | ######## | < 0.001 | |

| SDs in Autosomes | SDs in HSAY | P value | < 92% | |

| N | 3273 | 132 | ||

| K | 0.0958 | 0.0976 | 0.001 | |

| Size | 4,689.73 | 12,290.17 | < 0.001 | |

| Telomeres (10 Mb) | ID | |||

| SDs not in telomeres | SDs in Telomeres | P-value | > 98% | |

| N | 719 | 170 | ||

| K | 0.0105 | 0.0115 | 0.052 | |

| Size | 44,040.90 | 30,437.11 | 0.01 | |

| SDs not in telomeres | SDs in Telomeres | P-value | < 92% | |

| N | 2831 | 442 | ||

| K | 0.0958 | 0.0958 | 0.874 | |

| Size | 4,746.56 | 4,325.72 | 0.224 | |

| Centromere (5 Mb) | ID | |||

| SDs not in Centromeres | SDs in Centromeres | P-value | > 98% | |

| N | 572 | 147 | ||

| K | 0.0106 | 0.01 | 0.316 | |

| Size | 36,111.33 | 74,896.07 | < 0.001 | |

| SDs not in Centromeres | SDs in Centromeres | P-value | < 92% | |

| N | 2096 | 735 | ||

| K | 0.0959 | 0.0953 | 0.029 | |

| Size | 3,908.13 | 7,137.51 | < 0.001 | |

| HSA19 | ID | |||

| SDs in other autosomes | SDs in HSA19 | P-value | > 98% | |

| N | 561 | 11 | ||

| K | 0.0105 | 0.0126 | 0.32 | |

| Size | 36,600.01 | 11,188.90 | 0.139 | |

| SDs in other autosomes | SDs in HSA19 | P-value | < 92% | |

| N | 2029 | 67 | ||

| K | 0.0959 | 0.0958 | 0.906 | |

| Size | 3,875.29 | 4,902.67 | 0.141 | |

| Rearranged Chromosomes | ID | |||

| SDs in Colinear chr | SDs in Rearranged Chr | P-value | > 98% | |

| N | 208 | 353 | ||

| K | 0.0114 | 0.01 | 0.009 | |

| Size | 25,385.48 | 43,208.01 | < 0.001 | |

| SDs in Colinear chr | SDs in Rearranged Chr | P-value | < 92% | |

| N | 890 | 1139 | ||

| K | 0.0959 | 0.096 | 0.902 | |

| Size | 3,791.72 | 3,940.59 | 0.534 | |

| Inside rearranged regions versus Outside rearranged regions, without HSA2 | ID | |||

| SDs Outside rearranged regions | SDs Inside rearranged regions | P-value | > 98% | |

| N | 216 | 87 | ||

| K | 0.0104 | 0.0096 | 0.347 | |

| Size | 40,400.12 | 55,156.56 | 0.058 | |

| SDs Outside rearranged regions | SDs Inside rearranged regions | P-value | < 92% | |

| N | 715 | 267 | ||

| K | 0.096 | 0.0957 | 0.586 | |

| Size | 3,879.46 | 4,868.64 | 0.016 | |

| Inversions detected in (Newman et al 2005) vs rest of chromosomes | ID | |||

| SDs Outside Inversion | SDs Inside Inversion | P-value | > 98% | |

| N | 541 | 20 | ||

| K | 0.0104 | 0.0131 | 0.063 | |

| Size | 35,170.62 | 75,264.90 | 0.003 | |

| SDs Outside Inversion | SDs Inside Inversion | P-value | < 92% | |

| N | 1977 | 52 | ||

| K | 0.0959 | 0.0986 | 0.004 | |

| Size | 3,853.94 | 4,686.98 | 0.281 | |

| Breakpoints versus inverted chromosomes (excluding HSA2) | ID | |||

| SDs rest of Chr | SDs in BKP | P-value | > 98% | |

| N | 286 | 17 | ||

| K | 0.0103 | 0.008 | 0.135 | |

| Size | 44,189.30 | 52,171.11 | 0.611 | |

| SDs rest of Chr | SDs in BKP | P-value | < 92% | |

| N | 953 | 29 | ||

| K | 0.096 | 0.0941 | 0.15 | |

| Size | 4,159.23 | 3,792.82 | 0.748 | |

Divergence (K) is calculated as the number of substitution per site between the two duplication alignments. Length (Size) corresponds to the aligned basepairs. P-values are calculated by means of permutation test (see Material and Methods).

Regarding the position of SDs along chromosomes, we first considered telomeres. Only young SDs located in telomeres showed higher divergence between paralogous copies. They also showed shorter alignment sizes. On the contrary, old SDs did not present divergence differences between telomeres and the rest of the genome. When focusing on centromeres, we found that SDs near them are longer in both subsets (young and old SDs). As to divergence, only old SDs showed a slight decrease of paralogous divergence in pericentromeric regions compared to SDs located elsewhere in the genome.

HSA19 has been shown to have atypical divergence and nucleotide composition patterns. It presents higher divergence between human and mice, higher GC content, and an accumulation of DNA binding genes [53,54]. Also, HSA19 appears to have a deficit of interspersed SDs (as opposed to tandem) [5,53]. Surprisingly, our analysis shows that SDs located in this chromosome did not differ from SDs in other autosomes, neither in their length nor their divergence rates.

When we finally compared paralogous copies of human SDs located in rearranged chromosomes versus SDs located in colinear chromosomes, the only detectable patterns were that young SDs are significantly longer and less divergent when located in rearranged chromosomes. However, this observation can not be exclusively attributed to inversions; because when comparing divergence among copies of human SDs within the inverted regions (recall that most rearrangements took place in the chimpanzee lineage) versus SDs outside the inversion in rearranged chromosomes, there were no divergence differences, although SDs were longer within rearranged regions. Since evolutionary breakpoints are enriched with SDs in many species [8-12], we assessed the sequence features of SDs located at the breakpoints of inversions separating humans and chimpanzees. Neither the length nor the divergences of those SDs are statistically different from SDs located elsewhere in the genome.

Finally, we considered a set of small inversions recently detected in silico [55]. SDs located within these inversions showed a slight increase in divergence (highly significant for old SDs and marginally significant for young SDs). Only young SDs showed a remarkable increase of length within those rearrangements.

The distribution of divergence between human and chimpanzee SDs

We used Dataset 3 (Non-overlapping interspecific dataset, see Methods) to study divergence between human and chimpanzee SDs. This dataset is formed by two subsets of SDs: first, a subset non-overlapping human SDs for which we have measures of divergence from chimpanzee; and second, a subset of non-overlapping chimpanzee SDs for which we have measures of divergence from human (see Additional file 2). Again, we studied the effect of all the factors considered above in the divergence of SDs among species by sequentially analyzing and removing every individual factor (Table 4).

Table 4.

Average of inter-specific divergences in human SDs and chimpanzee SDs relative to genomic factors and rearrangements between human and chimpanzees.

| HUMAN SD | X-Chromosome | Y-Chromosome | Telomeres vs. rest of genome | Centromeres vs. rest of genome | Chromosome 19 | |||||

| vs. Autosomes | vs. Autosomes | |||||||||

| SDs in autosomes | SDs in the HSAX. | SDs in autosomes | SDs in the HSAY. | SDs outside Telomeres | SDs within Telomeres | SDs outside Centromeres | SDs within Centromeres | SDs outside HSA19 | SDs within HSA19 | |

| N | 1303 | 109 | 1303 | 51 | 1052 | 251 | 742 | 310 | 714 | 28 |

| Divergence | 0.0238 | 0.0161 | 0.0238 | 0.0259 | 0.0233 | 0.026 | 0.0228 | 0.0247 | 0.0225 | 0.0285 |

| P-value | < 0.001 | 0.087 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| CHIMP SD | X-Chromosome | Y-Chromosome | Telomeres vs. rest of genome | Centromeres vs. rest of genome | Chromosome 19 | |||||

| vs. Autosomes | vs. Autosomes | |||||||||

| SDs in autosomes | SDs in the HSAX. | SDs in autosomes | SDs in the HSAY. | SDs outside Telomeres | SDs within Telomeres | SDs outside Centromeres | SDs within Centromeres | SDs outside HSA19 | SDs within HSA19 | |

| N | 1415 | 110 | 1415 | 87 | 1224 | 191 | 789 | 435 | 779 | 10 |

| Divergence | 0.0222 | 0.0156 | 0.0222 | 0.0223 | 0.0217 | 0.0252 | 0.021 | 0.0231 | 0.0207 | 0.038 |

| P-value | < 0.001 | 0.891 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| HUMAN SD | Rearranged vs. | SDs within vs. | ||||||||

| Colinear chromosomes | outside rearranged regions (excluding HSA2) | |||||||||

| SDs in colinear chr. | SDs in Rearranged chr. | P-value | SDs Outside inversions | SDs inside inversions | P-value | |||||

| N | 267 | 447 | 280 | 112 | ||||||

| Divergence | 0.0236 | 0.0219 | 0.01 | 0.0218 | 0.0219 | 0.934 | ||||

| CHIMP SD | Rearranged vs. | SDs within vs. | ||||||||

| Colinear chromosomes | outside rearranged regions (excluding HSA2) | |||||||||

| SDs in colinear chr. | SDs in Rearranged chr. | P-value | SDs Outside inversions | SDs inside inversions | P-value | |||||

| N | 256 | 523 | 312 | 160 | ||||||

| Divergence | 0.0216 | 0.0203 | 0.025 | 0.0202 | 0.0199 | 0.693 | ||||

| HUMAN SD | Breakpoints vs. | |||||||||

| inverted chromosomes | ||||||||||

| (excludingHSA2) | ||||||||||

| SDs in Rearranged chr. | SDs in BKPs | P-value | ||||||||

| N | 370 | 22 | ||||||||

| Divergence | 0.0217 | 0.0242 | 0.136 | |||||||

| CHIMP SD | Breakpoints vs. | |||||||||

| inverted chromosomes | ||||||||||

| (excludingHSA2) | ||||||||||

| SDs in Rearranged chr. | SDs in BKPs | P-value | ||||||||

| N | 441 | 31 | ||||||||

| Divergence | 0.0201 | 0.0194 | 0.552 | |||||||

| HUMAN SD | SDs within vs. outside rearranged regions | |||||||||

| (excluding breakpoints and HSA2) | ||||||||||

| SDs Outside inversions | SDs inside inversions | P-value | ||||||||

| N | 264 | 106 | ||||||||

| Divergence | 0.0216 | 0.022 | 0.619 | |||||||

| CHIMP SD | SDs within vs. outside rearranged regions | |||||||||

| (excluding breakpoints and HSA2) | ||||||||||

| SDs Outside inversions | SDs inside inversions | P-value | ||||||||

| N | 291 | 150 | ||||||||

| Divergence | 0.0202 | 0.0199 | 0.583 | |||||||

| HUMAN SD | inversions (Newman et al. 2005) versus rest chromosomes | |||||||||

| SDs Outside inversions | SDs inside inversions | P-value | ||||||||

| N | 670 | 44 | ||||||||

| Divergence | 0.0227 | 0.0196 | 0.015 | |||||||

| CHIMP SD | inversions (Newman et al. 2005) chromosomes | |||||||||

| SDs Outside inversions | SDs inside inversions | P-value | ||||||||

| N | 713 | 66 | ||||||||

| Divergence | 0.021 | 0.0183 | 0.004 | |||||||

Divergence is calculated as the number of substitution per site between the two duplication alignments.

Our first observation was that SDs located in HSAX showed lower divergence than SDs in autosomes. This effect was consistent for both datasets of inter-specific SD divergence. Second, regions near telomeres presented higher divergence than the rest of the chromosome, just as previously seen for single-copy DNA in other studies [51,40]. This pattern was again consistent for both human and chimpanzee subsets of SDs. In contrast, and contrary to other studies [40,41], inter-specific divergence in SDs is higher near pericentromeric regions. Finally, SDs in HSA19 present higher divergence than SDs in other autosomes (Table 4).

Regarding the effect of rearrangements over interspecific SD divergence, we found that SDs within rearranged chromosomes diverged less than SDs in colinear chromosomes, which is in agreement with the most recent results for single copy genes [40]. In contrast to previous results, there were no significant divergence differences between SDs within versus SDs outside rearranged regions. Finally, and again differing from results in single copy genes [40], SDs located within small inversions [55] revealed lower divergence rates compared to SDs located elsewhere in the genome. To unveil any specific individual contributions of chromosomes, we analyzed interspecific divergence for every inversion (Table 5). There was no clear pattern to be detected. Only HSA9 presented higher divergence within its inversion and only when considering the subset of chimpanzee SDs.

Table 5.

Average of inter-divergences in human SDs and chimpanzee SDs in individual chromosomes relative to major rearrangements between human and chimpanzee.

| Hs Chr | Human SDs | Chimp SDs | |||||||||

| Outside rearranged regions | Inside rearranged regions | P-value | Nout | Nin | Outside rearranged regions | Inside rearranged regions | P-value | Nout | Nin | Lineage of the rearrangement | |

| HSA1 | 0.0209 | 0.0070 | 0.043 | 106 | 1 | 0.0203 | 105 | 0 | HUMAN | ||

| HSA4 | 0.0246 | 0.0263 | 0.608 | 17 | 13 | 0.0247 | 13 | 0 | CHIMP | ||

| HSA5 | 0.0226 | 0.0170 | 0.116 | 10 | 16 | 0.0197 | 0.0161 | 0.065 | 10 | 57 | CHIMP |

| HSA9 | 0.0230 | 0.0246 | 0.440 | 35 | 26 | 0.0184 | 0.0232 | < 0.001 | 49 | 38 | CHIMP |

| HSA12 | 0.0201 | 0.0243 | 0.286 | 9 | 7 | 0.0216 | 0.0190 | 0.875 | 1 | 8 | CHIMP |

| HSA15 | 0.0251 | 0.0239 | 0.661 | 41 | 7 | 0.0224 | 0.0239 | 0.418 | 48 | 10 | CHIMP |

| HSA16 | 0.0188 | 0.0319 | 0.008 | 41 | 2 | 0.0181 | 0.0413 | 0.008 | 68 | 1 | CHIMP |

| HSA17 | 0.0215 | 0.0198 | 0.427 | 16 | 40 | 0.0225 | 0.0206 | 0.352 | 17 | 46 | CHIMP |

| HSA18 | 0.0245 | 5 | 0 | 0.0252 | 1 | 0 | HUMAN | ||||

| TOTAL (without HSA2) | 0.0218 | 0.0219 | 0.934 | 280 | 112 | 0.0202 | 0.0199 | 0.693 | 312 | 160 | |

Discussion

Several conclusions arise from our whole-genome SDs analysis. First, there is an accumulation of relatively recent human SDs within some chromosomes that carry an evolutionary rearrangement between human and chimpanzees. Seven of the nine major inversions between humans and chimpanzees occurred in the chimpanzee lineage (HSA4, HSA5, HSA9, HSA12, HSA15, HSA16 and HSA17), thus inversions cannot be the cause of that accumulation. The classical explanation of the accumulation would be that some of these young SDs predate the split of humans and chimpanzees and, thus, that they originated the inversions via non-allelic homologous recombination, but this seems unlikely in the light of their location. Our observations are consistent with an alternative scenario in which both chromosomal rearrangements and SDs are consequences of a third factor, perhaps regions of high instability [29,56]. This has been suggested in opposition to the idea that rearrangements and SDs are related only because highly similar regions promote rearrangements by non-allelic recombination [8-12]. A final possibility is that we are observing an excess of similar duplications in pericentromeric regions, specially in HSA5 and HSA9, in which there are an excess of young human SDs (> 98% ID) within regions that were inverted in chimpanzees. Even if we endeavored to remove the effect of centromeres, the possibility remains that particularly strong local effects were not accounted for. Only further research on primate SDs will allow to ascertain the involved phenomena and the order in which they occurred.

Several authors have found that the association among rearrangement breakpoints and segmental duplications is maintained between different lineages, but not within the same lineage [6,9,13]. For instance, primate segmental duplications occur at specific locations that are enriched for mouse-human synteny and mouse-rat synteny breaks. As the majority of synteny rearrangements have occurred in the rodent lineage, there cannot be a causal relationship between the two. Rather, it must be the case that primate segmental duplications tend to appear at the same locations in which rodent chromosomes have rearranged. Thus, instability would seem a long standing property of these genomes at these locations. In addition, She et al. [5] described a non-uniform distribution of intrachromosomal human SDs and highlighted nine autosomal human chromosomes with an excess of young human SDs, seven of which presented rearrangements between humans and chimpanzees (out of which five were chimpanzee specific). These observations provide evidence for a link between expansions of recent SDs in one lineage and chromosomal rearrangements in the other. Only deeper analysis of the two chimpanzee chromosomes that carry human-specific rearrangements (HSA1 and HSA2) will help to clarify any direct relationship among chromosomal rearrangements and expansion of SDs. This analysis, however, is beyond the scope of the present work and would require a higher quality sequence assembly of the chimpanzee genome.

Several explanations can be put forward as to why chromosomal rearrangements and young SDs should accumulate in sister lineages. The first one relates to the aforementioned instability regions. A recent change in the understanding of the evolution and behavior of SDs [56-58] poses that there are "core elements" that may act as sources for the dispersal of new SDs, by creating a large number of copies of themselves. These copies tend to cluster by means of local duplications. Thus, one explanation for our results would be that some core elements were present in the chromosomes ancestral to those that currently harbor inversions and SDs in humans and chimpanzees. As inversions decrease recombination between homologous chromosomes [31-33], core elements becoming active and expanding by local copies in a given class of chromosome, would be less likely to be eliminated by recombination from their source regions while rearrangements are still segregating in the ancestral population. Thus, these core elements would accumulate copies of themselves only in the lineage in which they appeared. Moreover, the reduction of recombination caused by inversions [59] may also prevent the dispersal of the other associated SDs (not just the "core" elements). SDs trapped within rearrangements would be more similar to the "original" state because they would be prevented from invading other regions or chromosomes that could affect mutation rates and thus produce highly divergent SDs copies.

A second possibility is that lower recombination rates themselves could help explain our results. As suggested in previous work [60-63], there is a positive correlation among low recombination rates, low diversity within species, and low divergence that can be explained by a mutagenic effect of recombination. While inversions are segregating, regions within rearrangements have lower recombination rates and, thus, they should present lower divergence (either inter-specific or intra-specific). Of course, this would only be the case if rearrangements had been segregating in the population for a long time, so that the reduction of recombination could have a detectable impact on mutation rates.

Finally, some of the pairwise alignments classified as young SDs may in fact not be young, but their high identity may have been maintained by gene conversion [6]. Gene conversion is a homogenizing force that might erase differences among copies leading to underestimations of the age of SDs. It is possible that during the segregation of new rearrangements, the resolving structure of the few recombination events taking place within inversions would be biased towards increased gene conversion instead of the reciprocal exchange of chromatids. This would help explain the excess of highly similar tracks of SDs in one lineage together with inversions in the other lineage. However, this possibility implies that most gene conversion events ought to have happened before the separation of the two lineages and while the inversions were segregating in the population, which is unlikely. Moreover, She et al. [5] concluded that gene conversion events can not explain most of the high sequence identity of SD copies.

Secondly, we conclude that old and young SDs evolve at different rates when compared to single-copy DNA, hinting at different evolutionary trajectories for different SD classes. It is possible that young SDs are reflecting the history of recent primate evolution – which led to our species – while old SDs may reflect periods of duplication early during primate evolution. Our results, for example, support a recent expansion of young SDs or a more complex interaction among recombination and SDs. The latter appears to be the case for SDs in telomeres, where young SDs are marginally more divergent, but are significantly shorter than elsewhere in the genome, maybe as a result of telomeres having higher rates of recombination [64,65]. In contrast, older SDs do not show this trend, which could be expected since telomeres are likely to have moved during primate evolution [66,67].

Regarding centromeres, and probably as a result of their decreased recombination rates [64,65], we obtained larger sizes of pairwise alignments of SDs. However, as centromeres have been reported to be prone to repositioning during evolution [68], this result could be reflecting some other cause rather than a direct recombination effect. SDs in HSAY are also longer, which could be related to the lack of recombination in that chromosome or with recent, HSAY-specific, SD expansions.

Our main conclusion regarding major rearrangements between humans and chimpanzees is that young SDs located in rearranged chromosomes are longer and exhibit greater sequence identity than SDs located in colinear chromosomes. This could be expected, since rearrangements are known to be either human or chimpanzee specific and, thus, old SDs should not be affected by such recent rearrangements. Still, both young and old paralogous copies of SDs tend to be larger within rearranged chromosomal regions. This is also the case for smaller rearrangements that have been detected in silico [55]. These are puzzling patterns, hinting at some period of decreased recombination within rearranged regions. Finally, we observed higher levels of intraspecific divergence between SDs within smaller inversions [55]. Altogether, these data suggest that chromosomal rearrangements might have affected SD divergence rates during primate evolution.

Our third and last finding is that interspecific SD divergence displays rates and patterns that are roughly equivalent to those of single-copy DNA. SDs located in telomeres and in HSA19 show higher levels of interspecific SD divergence. Also, SDs located in rearranged chromosomes show lower divergence between species. Still, there are some discrepancies between single-copy and duplicated DNA, such as the higher divergence between SDs located in centromeres or the lower divergence of SDs within small inversions. Finally, HSAY does not show the higher degree of divergence reported for single-copy DNA [40-42], perhaps as the result of the recent expansion of young SDs in that chromosome [5] or of extensive gene conversion [69].

As to individual inversions, HSA9 stands out as the only chromosome showing significantly higher human-chimpanzee divergence within its rearrangement. This suggests a burst of interspecific divergence within the inversion, that could perhaps predate speciation. Therefore, HSA9 is currently the best candidate to further study any potential relationship among SDs, rearrangements, divergence, and speciation. If chromosomes have played any role in any of the speciation events that led to humans and chimpanzees, it is clear that not all of them would have made the same contributions and, thus, would not bear the same molecular signatures. We should keep this in mind when trying to explain why HSA4, which presents high divergence of single copy DNA located within its inversion [40], does not present any particular pattern when considering its duplications. Also, certain chromosomes (such as HSA4, HSA5, HSA9, HSA15 and HSA16) have been pinpointed as the most dissimilar between humans and chimpanzees in terms of the expression intensities of their genes [70], findings which are only partially consistent with the results presented here.

Conclusion

In summary, we conclude that some rearrangements in the human and chimpanzee genome may be associated with dynamic regions in the genome that may result in rearrangements in one lineage and duplications in the other, although the effect is not seen in all chromosomes. On the other hand, intraspecific and interspecific divergences between SDs are affected by the same factors which were known to affect divergence rates of single copy DNA sequences. Although chromosomal rearrangements do affect the evolution and fate of SDs, chromosomal speciation (and its relation with SDs novelties) does not seem to have been a common process along the human and chimpanzee lineages. Still, HSA9 is the best possible candidate to have been involved in some complex interaction among rearrangements, SDs, and evolutionary novelties. Studies which include more species and focus on the powerful novelty-generating force of segmental duplications are needed to increase our knowledge of this exciting topic.

Methods

Structural information

Coordinates of telomeres and centromeres of all chromosomes were obtained from Build 35 of the human genome and NCBI Build 1 of the chimpanzee genome [71]. We considered as rearranged chromosomes all those for which major chromosomal rearrangements in either the human or the chimpanzee lineages have been evidenced by recent in silico [51,72] or cytological structures [73-77]. This comprised HSA1, HSA4, HSA5, HSA9, HSA12, HSA15, HSA16, HSA17 and HSA18, which differ by a pericentric inversion, and human chromosome 2, which has been generated by an ancestral telomere-telomere fusion [78]. For all chromosomes, all in silico-estimated coordinates were compared with newly available cytological data in order to confirm inversion coordinates, as previously done [40]. When indicated, the mini-inversions detected "in silico" by [55] have been used.

Source of SD data

We retrieved information of segmental duplication about Human and Chimpanzee SDs from the Segmental Duplication Database [79,80]. In brief, we used the whole genome assembly comparison (WGAC), composed by SDs that were detected by the Blast-based method [1] to identify pairwise of DNA sequence of high similarity within the human assembly (Build 35).

Three datasets were built for analysis.

1) Dataset 1. Raw dataset. This is the standard dataset as downloaded from the Segmental Duplication Database. It contains pairs of coordinates of fragments of the human genome that fit two criteria: each pair has a minimum overlap size of 1 kb and presents > 90% identity among copies. [1]. A divergence measure was calculated for every pairwise detection as the number of substitutions per site (applying Jukes-Cantor correction). Besides divergence we also recorded the overlapping size (length) of every pair.

2) Dataset 2. Non-overlapping intraspecific dataset. Because of the methodology used in WGAC, most fragments in the raw dataset are repeated in many partially overlapping pairs, thus adding the same information several times especially in SD clusters. To eliminate this redundant information, we constructed a new dataset containing samples of SDs representative of every region of the genome covered by SD.

The steps used to construct our new dataset were as follows:

2.a. We constructed a "coverage map of SDs". We recorded the bound coordinates of overlapping SDs thus reporting every region in the human genome in which there are SDs. If two coverage zones were separated by a distance lower than 10 kb we joined them to avoid over-representing some parts of the genome. This procedure is similar that the one used in [5], when constructing "duplication hubs", that is, regions with an excess of aligned SDs.

2.b. From this coordinate list and for every "covered" region, we kept only one pair of SD as a representative of the region. The criteria to select one SD against the others were (1) Longer SDs were preferred, as measured by percentage of occupancy within that coverage zone and (2) SDs that had both paralogous copies in the same class of regions. That is, if one coverage zone is in, say, a telomere, we kept the longer SD having its paralogous copy also in a telomere. In case of not having copies in comparable regions, we just keep the longest. We considered seven classes of genomic location: sex chromosomes, telomeres, centromeres, HSA19, colinear chromosomes, colinear regions in rearranged chromosomes, rearranged regions (inversions) and rearrangement breakpoints. The goal of these criteria is to retrieve some non-redundant basic information of this portion of the genome. (see Additional file 1 for a schematic view of the process).

The coverage map to create the non-overlapping datasets was constructed a posteriori of the splitting between "young" and "old" duplications. This was done to avoid a bias the selection of a sample SDs for every region. A bias could have been possible since old segmental duplications are shorter than young ones, probably as a result of recombination or subsequent deletion events that breakdown their structure [5]. Thus, if we followed our criteria (for instance the higher coverage criterion (see Methods)) before splitting between young and old SDs, the latter would have had lower probabilities of being selected as a sample of the region of interest

3) Dataset 3. Non-overlapping interspecific dataset. This third dataset was designed to recover a sample of divergence between humans and chimpanzees in regions covered by SDs. From the coverage map of human SD we recovered chimpanzee WGS (v1) sequences [5]. For every "covered" zone (a slice of coordinates), we split it in non overlapping windows of 5000 bp. For every one of those windows, divergence was calculated as the average of all chimpanzee WGS sequences against the human sequence. Finally the average of all windows was computed as the average divergence of the coverage zone. Divergence was calculated applying Kimura's correction. We also constructed a parallel dataset computing divergence of the chimpanzee SDs from human WGS sequences (see Additional file 2).

These three datasets were built in order to tackle different questions. To detect clusters of SDs in some parts of the genome we used the raw dataset, which provides a good perspective of the amount of SDs in every region. When we aim to study divergence in different regions of the genome while avoiding some biases such as overlapping SDs or copies in non-comparable regions of the genome, we should use the non overlapping datasets, either for intraspecific divergence (dataset 2) or interspecific divergence (dataset 3).

Filtering

Previous to every analysis we performed a sequential filtering process to remove the genomic variables that are known to affect evolutionary rates in single copy DNA. These factors include linkage to sex chromosomes [47,81-83], to telomeres (10 Mb from the tip of chromosome) [51], to centromeres (5 Mb around them) [49,50,84] and to human chromosome 19 (HSA19) [53]. After getting the result for each one of the categories, those SDs located in that specific category were removed from the analysis. As an example, after analyzing the effect of sex chromosomes on our SDs dataset, we removed SDs in sex chromosomes and analyzed the effect of telomeres on the remaining dataset. We also eliminated pairs of SDs that had one copy in rearranged regions and the other copy in colinear regions (since it is impossible to classify that pair as SDs in rearranged or collinear regions).

Permutation tests

SDs divergence measures in different categories were compared by means of pairwise permutation tests (based on 1000 permutations). Empirical P-values in such tests, are calculated as the proportion of times that the difference of averages between two categories in a permuted dataset is equal or larger than the observed difference.

Authors' contributions

TM–B, EEE and AN designed the overall project. TM–B, ZC, XS and AN analyzed the data. TM–B and AN wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Construction of Dataset 2 (Non-overlapping intraspecific dataset). There are the 3 main steps to construct Dataset 2. STEP1, we constructed the "coverage map", basically we recorded the bound coordinates of overlapping SDs. STEP 2, we labeled every SD as belonging to telomeres, centromeres, HSA19, sexual chromosomes, inverted and non-rearranged zones and breakpoints. STEP 3, we kept as a sample of the region in the "coverage map" those SDs that ha d the longer paralogous copy in an equivalently labeled region.

The construction of Dataset 3 (Non-overlapping, interspecific divergence dataset). We split every zone in the coverage map of WGS chimpanzee reads in windows of 5000 bp. For every one of those inner windows, divergence (K_w i) was calculated as the average of divergences of every chimpanzee read against human sequence (B35) (see B). Finally the averages of all windows were joined in a single average divergence of the coverage zone (K total) (see A)

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We want to thank J. Bertranpetit, E. Gazave, O. Fernando, M. Przeworski, T. Newman, A. Sharp and the members of the Evolutionary Biology Unit in UPF and Evan Eichler's lab at University of Washington for enriching discussions and lots of help during the preparation of this work. This research was supported by a grant to A.N. from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologia (Spain, BFU2006 15413-C02-01) and by BE2005 and BP2006 fellowships to T.M.B from the "Departament d'Educació i Universitats de la Generalitat de Catalunya".

Contributor Information

Tomàs Marques-Bonet, Email: tmarques@u.washington.edu.

Ze Cheng, Email: ginger@gs.washington.edu.

Xinwei She, Email: xws@gs.washington.edu.

Evan E Eichler, Email: eee@gs.washington.edu.

Arcadi Navarro, Email: arcadi.navarro@upf.edu.

References

- Bailey JA, Yavor AM, Massa HF, Trask BJ, Eichler EE. Segmental duplications: Organization and impact within the current Human Genome Project assembly. Genome Research. 2001;11:1005–1017. doi: 10.1101/gr.GR-1871R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Gu ZP, Clark RA, Reinert K, Samonte RV, Schwartz S, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Eichler EE. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science. 2002;297:1003–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1072047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J, Estivill X, Khaja R, MacDonald JR, Lau K, Tsui LC, Scherer SW. Genome-wide detection of segmental duplications and potential assembly errors in the human genome sequence. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-4-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardopoulou EV, Williams EM, Fan Y, Friedman C, Young JM, Trask BJ. Human subtelomeres are hot spots of interchromosomal recombination and segmental duplication. Nature. 2005;437:94–100. doi: 10.1038/nature04029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She XW, Liu G, Ventura M, Zhao S, Misceo D, Roberto R, Cardone MF, Rocchi M, Green ED, Archidiacano N, Eichler EE. A preliminary comparative analysis of primate segmental duplications shows elevated substitution rates and a great-ape expansion of intrachromosomal duplications. Genome Research. 2006;16:576–583. doi: 10.1101/gr.4949406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Ventura M, She XW, Khaitovich P, Graves T, Osoegawa K, Church D, DeJong P, Wilson RK, Paabo S, Rocchi M, Eichler EE. A genome-wide comparison of recent chimpanzee and human segmental duplications. Nature. 2005;437:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature04000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AJ, Cheng Z, Eichler EE. Structural Variation of the Human Genome. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006 doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armengol L, Pujana MA, Cheung J, Scherer SW, Estivill X. Enrichment of segmental duplications in regions of breaks of synteny between the human and mouse genomes suggest their involvement in evolutionary rearrangements. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12:2201–2208. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Baertsch R, Kent WJ, Haussler D, Eichler EE. Hotspots of mammalian chromosomal evolution. Genome Biology. 2004;5 doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-4-r23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samonte RV, Eichler EE. Segmental duplications and the evolution of the primate genome. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2002;3:65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrg705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AJ, Locke DP, McGrath SD, Cheng Z, Bailey JA, Vallente RU, Pertz LM, Clark RA, Schwartz S, Segraves R, Oseroff VV, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Eichler EE. Segmental duplications and copy-number variation in the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:78–88. doi: 10.1086/431652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Eichler EE, Schwartz S, Nicholls RD. Structure of chromosomal duplicons and their role in mediating human genomic disorders. Genome Res. 2000;10:597–610. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan A, Eichler EE, Oliver SG, Paterson AH, Stein L. Chromosome evolution in eukaryotes: a multi-kingdom perspective. Trends Genet. 2005;21:673–682. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler EE, Sankoff D. Structural dynamics of eukaryotic chromosome evolution. Science. 2003;301:793–797. doi: 10.1126/science.1086132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankiewicz P, Shaw CJ, Withers M, Inoue K, Lupski JR. Serial segmental duplications during primate evolution result in complex human genome architecture. Genome Research. 2004;14:2209–2220. doi: 10.1101/gr.2746604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR. Genomic disorders: structural features of the genome can lead to DNA rearrangements and human disease traits. Trends Genet. 1998;14:417–422. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(98)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw CJ, Lupski JR. Implications of human genome architecture for rearrangement-based disorders: the genomic basis of disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 2004;13:R57–R64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Genome architecture, rearrangements and genomic disorders. Trends in Genetics. 2002;18:74–82. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courseaux A, Nahon JL. Birth of two chimeric genes in the Hominidae lineage. Science. 2001;291:1293–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.1057284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME, Viggiano L, Bailey JA, Abdul-Rauf M, Goodwin G, Rocchi M, Eichler EE. Positive selection of a gene family during the emergence of humans and African apes. Nature. 2001;413:514–519. doi: 10.1038/35097067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler EE. Segmental duplications: What's missing, misassigned, and misassembled - and should we care? Genome Research. 2001;11:653–656. doi: 10.1101/gr.188901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan IK, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Duplicated genes evolve slower than singletons despite the initial rate increase. Bmc Evolutionary Biology. 2004;4 doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad DF, Andrews TD, Carter NP, Hurles ME, Pritchard JK. A high-resolution survey of deletion polymorphism in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:75–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Troge J, Alexander J, Young J, Lundin P, Maner S, Massa H, Walker M, Chi M, Navin N, Lucito R, Healy J, Hicks J, Ye K, Reiner A, Gilliam TC, Trask B, Patterson N, Zetterberg A, Wigler M. Large-scale copy number polymorphism in the human genome. Science. 2004;305:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1098918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Gu ZL, Li WH. Different evolutionary patterns between young duplicate genes in the human genome. Genome Biology. 2003;4:R56. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-r56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant GC, Wagner A. Asymmetric sequence divergence of duplicate genes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2052–2058. doi: 10.1101/gr.1252603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290:1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov FA, Rogozin IB, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Selection in the evolution of gene duplications. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0008. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-2-research0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranz JM, Maurin D, Chan YS, von Grotthuss M, Hillier LW, Roote J, Ashburner M, Bergman CM. Principles of Genome Evolution in the Drosophila melanogaster Species Group. Plos Biology (In press) 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Casals F, Navarro A. Inversions – the chicken or the egg? Plos Biology (News & Comments) (In press) 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Navarro A, Barton NH. Accumulating postzygotic isolation genes in parapatry: A new twist on chromosomal speciation. Evolution. 2003;57:447–459. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH. Chromosomal rearrangements and speciation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2001;16:351–358. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noor MAF, Grams KL, Bertucci LA, Reiland J. Chromosomal inversions and the reproductive isolation of species. P Natl Acad Sci USA P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12084–12088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221274498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick M, Barton N. Chromosome inversions, local adaptation and speciation. Genetics. 2006;173:419–434. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A, Barton NH. Chromosomal speciation and molecular divergence - Accelerated evolution in rearranged chromosomes. Science. 2003;300:321–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1080600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Li WH, Wu CI. Comment on "Chromosomal speciation and molecular divergence - Accelerated evolution in rearranged chromosomes". Science. 2003;302:988. doi: 10.1126/science.1088277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A, Marques-Bonet T, Barton NH. Response to comment on "chromosomal speciation and molecular divergence - Accelerated evolution in rearranged chromosomes". Science. 2003;302:988. doi: 10.1126/science.1090460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JZ, Wang XX, Podlaha O. Testing the chromosomal speciation hypothesis for humans and chimpanzees. Genome Research. 2004;14:845–851. doi: 10.1101/gr.1891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallender EJ, Lahn BT. Effects of chromosomal rearrangements on human-chimpanzee molecular evolution. Genomics. 2004;84:757–761. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques-Bonet T, Sànchez-Ruiz J, Armengol LL, Khaja R, Bertranpetit J, Rocchi M, Gazave E, Navarro A. On the association between chromosomal rearrangements and genic evolution in humans and chimpanzees. Genome Biol 2007 Oct 30;8 (10):R230 17971225. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marques-Bonet T, Navarro A. Chromosomal rearrangements are associated with higher rates of molecular evolution in mammals. Gene. 2005;353:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armengol L, Marques-Bonet T, Cheung J, Khaja R, Gonzalez JR, Scherer SW, Navarro A, Estivill X. Murine segmental duplications are hot spots for chromosome and gene evolution. Genomics. 2005;86:692–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblad-Toh K, Wade CM, Mikkelsen TS, Karlsson EK, Jaffe DB, Kamal M, Clamp M, Chang JL, Kulbokas EJ, 3rd, Zody MC, Mauceli E, Xie X, Breen M, Wayne RK, Ostrander EA, Ponting CP, Galibert F, Smith DR, DeJong PJ, Kirkness E, Alvarez P, Biagi T, Brockman W, Butler J, Chin CW, Cook A, Cuff J, Daly MJ, DeCaprio D, Gnerre S, Grabherr M, Kellis M, Kleber M, Bardeleben C, Goodstadt L, Heger A, Hitte C, Kim L, Koepfli KP, Parker HG, Pollinger JP, Searle SM, Sutter NB, Thomas R, Webber C, Baldwin J, Abebe A, Abouelleil A, Aftuck L, Ait-Zahra M, Aldredge T, Allen N, An P, Anderson S, Antoine C, Arachchi H, Aslam A, Ayotte L, Bachantsang P, Barry A, Bayul T, Benamara M, Berlin A, Bessette D, Blitshteyn B, Bloom T, Blye J, Boguslavskiy L, Bonnet C, Boukhgalter B, Brown A, Cahill P, Calixte N, Camarata J, Cheshatsang Y, Chu J, Citroen M, Collymore A, Cooke P, Dawoe T, Daza R, Decktor K, DeGray S, Dhargay N, Dooley K, Dooley K, Dorje P, Dorjee K, Dorris L, Duffey N, Dupes A, Egbiremolen O, Elong R, Falk J, Farina A, Faro S, Ferguson D, Ferreira P, Fisher S, FitzGerald M, Foley K, Foley C, Franke A, Friedrich D, Gage D, Garber M, Gearin G, Giannoukos G, Goode T, Goyette A, Graham J, Grandbois E, Gyaltsen K, Hafez N, Hagopian D, Hagos B, Hall J, Healy C, Hegarty R, Honan T, Horn A, Houde N, Hughes L, Hunnicutt L, Husby M, Jester B, Jones C, Kamat A, Kanga B, Kells C, Khazanovich D, Kieu AC, Kisner P, Kumar M, Lance K, Landers T, Lara M, Lee W, Leger JP, Lennon N, Leuper L, LeVine S, Liu J, Liu X, Lokyitsang Y, Lokyitsang T, Lui A, Macdonald J, Major J, Marabella R, Maru K, Matthews C, McDonough S, Mehta T, Meldrim J, Melnikov A, Meneus L, Mihalev A, Mihova T, Miller K, Mittelman R, Mlenga V, Mulrain L, Munson G, Navidi A, Naylor J, Nguyen T, Nguyen N, Nguyen C, Nguyen T, Nicol R, Norbu N, Norbu C, Novod N, Nyima T, Olandt P, O'Neill B, O'Neill K, Osman S, Oyono L, Patti C, Perrin D, Phunkhang P, Pierre F, Priest M, Rachupka A, Raghuraman S, Rameau R, Ray V, Raymond C, Rege F, Rise C, Rogers J, Rogov P, Sahalie J, Settipalli S, Sharpe T, Shea T, Sheehan M, Sherpa N, Shi J, Shih D, Sloan J, Smith C, Sparrow T, Stalker J, Stange-Thomann N, Stavropoulos S, Stone C, Stone S, Sykes S, Tchuinga P, Tenzing P, Tesfaye S, Thoulutsang D, Thoulutsang Y, Topham K, Topping I, Tsamla T, Vassiliev H, Venkataraman V, Vo A, Wangchuk T, Wangdi T, Weiand M, Wilkinson J, Wilson A, Yadav S, Yang S, Yang X, Young G, Yu Q, Zainoun J, Zembek L, Zimmer A, Lander ES. Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. Nature. 2005;438:803–819. doi: 10.1038/nature04338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DN, Youssoufian H. The CpG dinucleotide and human genetic disease. Hum Genet. 1988;78:151–155. doi: 10.1007/BF00278187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sved J, Bird A. The expected equilibrium of the CpG dinucleotide in vertebrate genomes under a mutation model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4692–4696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber C, Ponting CP. Hotspots of mutation and breakage in dog and human chromosomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:1787–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.3896805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WH, Yi SJ, Makova K. Male-driven evolution. Curr Opin Genet Dev Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:650–656. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe KH, Sharp PM. Mammalian Gene Evolution - Nucleotide-Sequence Divergence between Mouse and Rat. J Mol Evol. 1993;37:441–456. doi: 10.1007/BF00178874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MK, Willard HF. Analysis of the centromeric regions of the human genome assembly. Trends in Genetics. 2004;20:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She XW, Horvath JE, Jiang ZS, Liu G, Furey TS, Christ L, Clark R, Graves T, Gulden CL, Alkan C, Bailey JA, Sahinalp C, Rocchi M, Haussler D, Wilson RK, Miller W, Schwartz S, Eichler EE. The structure and evolution of centromeric transition regions within the human genome. Nature. 2004;430:857–864. doi: 10.1038/nature02806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen TS, Hillier LW, Eichler EE, Zody MC, Jaffe DB, Yang SP, Enard W, Hellmann I, Lindblad-Toh K, Altheide TK, Archidiacono N, Bork P, Butler J, Chang JL, Cheng Z, Chinwalla AT, deJong P, Delehaunty KD, Fronick CC, Fulton LL, Gilad Y, Glusman G, Gnerre S, Graves TA, Hayakawa T, Hayden KE, Huang XQ, Ji HK, Kent WJ, King MC, Kulbokas EJ, Lee MK, Liu G, Lopez-Otin C, Makova KD, Man O, Mardis ER, Mauceli E, Miner TL, Nash WE, Nelson JO, Paabo S, Patterson NJ, Pohl CS, Pollard KS, Prufer K, Puente XS, Reich D, Rocchi M, Rosenbloom K, Ruvolo M, Richter DJ, Schaffner SF, Smit AFA, Smith SM, Suyama M, Taylor J, Torrents D, Tuzun E, Varki A, Velasco G, Ventura M, Wallis JW, Wendl MC, Wilson RK, Lander ES, Waterston RH, Consortium CSA. Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:69–87. doi: 10.1038/nature04072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szamalek JM, Goidts V, Searle JB, Cooper DN, Hameister H, Kehrer-Sawatzki H. The chimpanzee-specific pericentric inversions that distinguish humans and chimpanzees have identical breakpoints in Pan troglodytes and Pan paniscus. Genomics. 2006;87:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana J. Genes on human chromosome 19 show extreme divergence from the mouse orthologs and a high GC content. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:1751–1756. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.8.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana J, Guigo R, Alba MM. Clustering of genes coding for DNA binding proteins in a region of atypical evolution of the human genome. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:72–79. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2605-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman TL, Tuzun E, Morrison VA, Hayden KE, Ventura M, McGrath SD, Rocchi M, Eichler EE. A genome-wide survey of structural variation between human and chimpanzee. Genome Research. 2005;15:1344–1356. doi: 10.1101/gr.4338005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME, Cheng Z, Morrison VA, Scherer S, Ventura M, Gibbs RA, Green ED, Eichler EE. Eukaryotic Transposable Elements and Genome Evolution Special Feature: Recurrent duplication-driven transposition of DNA during hominoid evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17626–17631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605426103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zody MC, Garber M, Adams DJ, Sharpe T, Harrow J, Lupski JR, Nicholson C, Searle SM, Wilming L, Young SK, Abouelleil A, Allen NR, Bi WM, Bloom T, Borowsky ML, Bugalter BE, Butler J, Chang JL, Chen CK, Cook A, Corum B, Cuomo CA, de Jong PJ, DeCaprio D, Dewar K, FitzGerald M, Gilbert J, Gibson R, Gnerre S, Goldstein S, Grafham DV, Grocock R, Hafez N, Hagopian DS, Hart E, Norman CH, Humphray S, Jaffe DB, Jones M, Kamal M, Khodiyar VK, LaButti K, Laird G, Lehoczky J, Liu XH, Lokyitsang T, Loveland J, Lui A, Macdonald P, Major JE, Matthews L, Mauceli E, McCarroll SA, Mihalev AH, Mudge J, Nguyen C, Nicol R, O'Leary SB, Osoegawa K, Schwartz DC, Shaw-Smith C, Stankiewicz P, Steward C, Swarbreck D, Venkataraman V, Whittaker CA, Yang XP, Zimmer AR, Bradley A, Hubbard T, Birren BW, Rogers J, Lander ES, Nusbaum C. DNA sequence of human chromosome 17 and analysis of rearrangement in the human lineage. Nature. 2006;440:1045–1049. doi: 10.1038/nature04689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zody M, Garber M, Sharpe T, Young S, Rowen L, O'Neill K, Whittaker C, Kamal M, Chang J, Cuomo C, Dewar K, Fitzgerald M, Kodira C, Madan A, Qin S, Yang X, Abbasi N, Abouelleil A, Arachchi H, Baradarani L, Birditt B, Bloom S, Bloom T, Borowsky M, Burke J, Butler J, Cook A, Dearellano K, Decaprio D, Dorris L, Dors M, Eichler E, Engels R, Fahey J, Fleetwood P, Friedman C, Gearin G, Hall J, Hensley G, Johnson E, Jones C, Kamat A, Kaur A, Locke D, Madan A, Munson G, Jaffe D, Lui A, Macdonald P, Mauceli E, Naylor J, Nesbitt R, Nicol R, O'Leary S, Ratcliffe A, Rounsley S, She X, Sneddon K, Stewart S, Sougnez C, Stone S, Topham K, Vincent D, Wang S, Zimmer A, Birren B, Hood L, Lander E, Nusbaum C. Nature. Vol. 440. Nature; 2006. Analysis of the DNA sequence and duplication history of human chromosome 15; pp. 671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A, Betran E, Barbadilla A, Ruiz A. Recombination and gene flux caused by gene conversion and crossing over in inversion heterokaryotypes. Genetics. 1997;146:695–709. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann I, Ebersberger I, Ptak SE, Paabo S, Przeworski M. A neutral explanation for the correlation of diversity with recombination rates in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1527–1535. doi: 10.1086/375657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyrewalker A. Recombination and Mammalian Genome Evolution. P Roy Soc Lond B Bio. 1993;252:237–243. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1993.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison RC, Roskin KM, Yang S, Diekhans M, Kent WJ, Weber R, Elnitski L, Li J, O'Connor M, Kolbe D, Schwartz S, Furey TS, Whelan S, Goldman N, Smit A, Miller W, Chiaromonte F, Haussler D. Covariation in frequencies of substitution, deletion, transposition, and recombination during eutherian evolution. Genome Res. 2003;13:13–26. doi: 10.1101/gr.844103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier J, Duret L. Recombination drives the evolution of GC-content in the human genome. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:984–990. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers S, Bottolo L, Freeman C, McVean G, Donnelly P. A fine-scale map of recombination rates and hotspots across the human genome. Science. 2005;310:321–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1117196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A, Gudbjartsson DF, Sainz J, Jonsdottir GM, Gudjonsson SA, Richardsson B, Sigurdardottir S, Barnard J, Hallbeck B, Masson G, Shlien A, Palsson ST, Frigge ML, Thorgeirsson TE, Gulcher JR, Stefansson K. A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nature Genetics. 2002;31:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Herrera A, Garcia F, Giulotto E, Attolini C, Egozcue J, Ponsa M, Garcia M. Evolutionary breakpoints are co-localized with fragile sites and intrachromosomal telomeric sequences in primates. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;108:234–247. doi: 10.1159/000080822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nergadze SG, Rocchi M, Azzalin CM, Mondello C, Giulotto E. Insertion of telomeric repeats at intrachromosomal break sites during primate evolution. Genome Res. 2004;14:1704–1710. doi: 10.1101/gr.2778904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy WJ, Larkin DM, Everts-van der Wind A, Bourque G, Tesler G, Auvil L, Beever JE, Chowdhary BP, Galibert F, Gatzke L, Hitte C, Meyers SN, Milan D, Ostrander EA, Pape G, Parker HG, Raudsepp T, Rogatcheva MB, Schook LB, Skow LC, Welge M, Womack JE, O'Brien S J, Pevzner PA, Lewin HA. Dynamics of mammalian chromosome evolution inferred from multispecies comparative maps. Science. 2005;309:613–617. doi: 10.1126/science.1111387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky H, Marszalek JD, Minx PJ, Cordum HS, Waterston RH, Wilson RK, Page DC. Abundant gene conversion between arms of palindromes in human and ape Y chromosomes. Nature. 2003;423:873–876. doi: 10.1038/nature01723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques-Bonet T, Caceres M, Bertranpetit J, Preuss TM, Thomas JW, Navarro A. Chromosomal rearrangements and the genomic distribution of gene-expression divergence in humans and chimpanzees. Trends in Genetics. 2004;20:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browser UCSCG. UCSC Genome Browser http://genome.ucsc.edu/

- Feuk L, MacDonald JR, Tang T, Carson AR, Li M, Rao G, Khaja R, Scherer SW. Discovery of human inversion polymorphisms by comparative analysis of human and chimpanzee DNA sequence assemblies. Plos Genetics. 2005;1:489–498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goidts V, Szamalek JM, Hameister H, Kehrer-Sawatzki H. Segmental duplication associated with the human-specific inversion of chromosome 18: a further example of the impact of segmental duplications on karyotype and genome evolution in primates. Human Genetics. 2004;115:116–122. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1120-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Sandig C, Chuzhanova N, Goidts V, Szamalek JM, Tanzer S, Muller S, Platzer M, Cooper DN, Hameister H. Breakpoint analysis of the pericentric inversion distinguishing human chromosome 4 from the homologous chromosome in the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Human Mutation. 2005;25:45–55. doi: 10.1002/humu.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Sandig CA, Goidts V, Hameister H. Breakpoint analysis of the pericentric inversion between chimpanzee chromosome 10 and the homologous chromosome 12 in humans. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2005;108:91–97. doi: 10.1159/000080806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Schreiner B, Tanzer S, Platzer M, Muller S, Hameister H. Molecular characterization of the pericentric inversion that causes differences between chimpanzee chromosome 19 and human chromosome 17. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:375–388. doi: 10.1086/341963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Szamalek JM, Tanzer S, Platzer M, Hameister H. Molecular characterization of the pericentric inversion of chimpanzee chromosome 11 homologous to human chromosome 9. Genomics. 2005;85:542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunis JJ, Prakash O. The Origin of Man - a Chromosomal Pictorial Legacy. Science. 1982;215:1525–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.7063861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimpanzee Segmental Duplication Database http://chimpparalogy.gs.washington.edu/

- Human Segmental Duplication Database http://humanparalogy.gs.washington.edu/

- Crow JF. A new study challenges the current belief of a high human male : female mutation ratio. Trends in Genetics. 2000;16:525–526. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst LD, Ellegren H. Sex biases in the mutation rate. Trends in Genetics. 1998;14:446–452. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(98)01577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makova KD, Li WH. Strong male-driven evolution of DNA sequences in humans and apes. Nature. 2002;416:624–626. doi: 10.1038/416624a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She XW, Jiang ZX, Clark RL, Liu G, Cheng Z, Tuzun E, Church DM, Sutton G, Halpern AL, Eichler EE. Shotgun sequence assembly and recent segmental duplications within the human genome. Nature. 2004;431:927–930. doi: 10.1038/nature03062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Construction of Dataset 2 (Non-overlapping intraspecific dataset). There are the 3 main steps to construct Dataset 2. STEP1, we constructed the "coverage map", basically we recorded the bound coordinates of overlapping SDs. STEP 2, we labeled every SD as belonging to telomeres, centromeres, HSA19, sexual chromosomes, inverted and non-rearranged zones and breakpoints. STEP 3, we kept as a sample of the region in the "coverage map" those SDs that ha d the longer paralogous copy in an equivalently labeled region.

The construction of Dataset 3 (Non-overlapping, interspecific divergence dataset). We split every zone in the coverage map of WGS chimpanzee reads in windows of 5000 bp. For every one of those inner windows, divergence (K_w i) was calculated as the average of divergences of every chimpanzee read against human sequence (B35) (see B). Finally the averages of all windows were joined in a single average divergence of the coverage zone (K total) (see A)