Abstract

A prominent feature of synaptic maturation at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is the topological transformation of the acetylcholine receptor (AChR)-rich postsynaptic membrane from an ovoid plaque into a complex array of branches. We show here that laminins play an autocrine role in promoting this transformation. Laminins containing the α4, α5, and β2 subunits are synthesized by muscle fibers and concentrated in the small portion of the basal lamina that passes through the synaptic cleft at the NMJ. Topological maturation of AChR clusters was delayed in targeted mutant mice lacking laminin α5 and arrested in mutants lacking both α4 and α5. Analysis of chimeric laminins in vivo and of mutant myotubes cultured aneurally demonstrated that the laminins act directly on muscle cells to promote postsynaptic maturation. Immunohistochemical studies in vivo and in vitro along with analysis of targeted mutants provide evidence that laminin-dependent aggregation of dystroglycan in the postsynaptic membrane is a key step in synaptic maturation. Another synaptically concentrated laminin receptor, Bcam, is dispensable. Together with previous studies implicating laminins as organizers of presynaptic differentiation, these results show that laminins coordinate post- with presynaptic maturation.

Introduction

A hallmark of the chemical synapse is the precise apposition of its pre- and postsynaptic specializations: neurotransmitter release sites in nerve terminals lie directly opposite concentrations of neurotransmitter receptors in the postsynaptic membrane. One mechanism for ensuring this coordination is the presentation by synaptic partners of factors that locally organize each other's differentiation. At the skeletal neuromuscular junction (NMJ), for example, agrin and acetylcholine secreted from axons pattern the postsynaptic membrane, and laminins and fibroblast growth factors secreted from the muscle pattern the nerve terminal (Noakes et al., 1995; Gautam et al., 1996; Burgess et al., 1999; Patton et al., 2001; Nishimune et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2005; Misgeld et al., 2005). However, recent studies have emphasized the ability of postsynaptic components, such as acetylcholine receptors (AChRs), to aggregate in the absence of innervation (Lin et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2001). Time-lapse imaging in vivo shows that some AChR aggregates are organized by the nerves, whereas others may be recognized by the nerve and incorporated into the synapse (Flanagan-Steet et al., 2005; Panzer et al., 2006). Partially redundant control by intrinsic and extrinsic patterning may help ensure that all muscle fibers end up with proper innervation (Kummer et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2008).

A combination of transsynaptic and cell-autonomous factors may also be responsible for postnatal maturation of the NMJ. During the first 2 wk after birth, the initially ovoid postsynaptic plaque of AChRs is transformed into a complex pretzel-shaped array of branches (Slater, 1982; Desaki and Uehara, 1987; Marques et al., 2000; Sanes and Lichtman, 2001). This process, which mirrors the postnatal branching of nerve terminals, was long assumed to reflect transsynaptic signaling because it fails to occur in neonatally denervated muscles, and because AChR aggregates in cultured myotubes generally remain plaque-shaped. Recently, however, we found that the plaque-to-pretzel transition can occur to a remarkable extent in myotubes cultured aneurally (Kummer et al., 2004). Thus, mechanisms must exist that coordinate the branching of pre- and postsynaptic structures as synapses mature.

How can such coordination be achieved? One attractive hypothesis is that some components of the synaptic cleft influence both pre- and postsynaptic differentiation. In support of this idea, we provide evidence here that laminins, muscle-derived synaptic organizers that promote presynaptic differentiation by an intercellular mechanism, also promote postsynaptic maturation by an autocrine mechanism. Laminins, which are heterotrimers of α, β, and γ subunits, are components of the basal lamina that ensheathes muscle fibers. Most of the basal lamina is rich in laminin 211 (=α2, β1 γ1; see Aumailley et al., 2005 for laminin nomenclature), and contains the β1 subunit. In contrast, the small fraction of the basal lamina that occupies the synaptic cleft at the NMJ bears little if any β1 but is rich in laminins 221, 421, and 521, all of which contain the β2 subunit (Patton et al., 1997). Laminin β2 promotes presynaptic differentiation, in part by binding to voltage-gated calcium channels in the presynaptic membrane (Noakes et al., 1995; Son et al., 1999; Nishimune, et al., 2004).

In attempting to determine roles of the individual laminin α chains associated with synaptic β2 (α2, α4, and α5 in laminins 221, 421, and 521, respectively), we found ultrastructural defects in alignment of pre- and postsynaptic specializations in mice lacking laminin α4 (Patton et al., 2001). Lack of laminin α2 also leads to modest neuromuscular defects, but these may be secondary to the muscular dystrophy that results from loss of laminin 211 (Law et al., 1983; Desaki et al., 1995; Patton et al., 2001). Roles of laminin α5 have been difficult to analyze because mice lacking laminin α5 (Lama5−/−) die at late embryonic stages because of multiple developmental defects, including exencephaly, syndactyly, and dysmorphogenesis of the placenta (Miner et al., 1998). Accordingly, we reexamined this issue using a conditional mutant (Nguyen et al., 2005) in which we could selectively remove laminin α5 from muscle. Postsynaptic maturation was delayed in mice lacking laminin α5 in muscle and arrested in double mutants lacking laminins α4 and α5. Further analysis, both in vivo and in vitro, provided evidence that laminin acts directly on myotubes to promote postsynaptic maturation and that this autocrine effect is mediated in large part by the transmembrane laminin receptor dystroglycan. Together, these results suggest that synaptic laminins act through distinct receptors as both retrograde organizers of presynaptic maturation and autocrine organizers of postsynaptic maturation. This dual role provides an elegant way to coordinate pre- and postsynaptic growth and differentiation as the synapse matures.

Results

Muscle-specific deletion of laminin α5

In initial studies, we examined muscles from targeted laminin α5 null mutant mice (Lama5−/−; Miner et al., 1998). NMJs formed in these mutants, with vesicle-rich nerve terminals apposed to postsynaptic AChR aggregates (Biernan, J., L. Knittel, D. Yang, Y.S. Tarumi, J.H. Miner, J.R. Sanes, and B.L. Patton. 2003. Society for Neuroscience 33rd Annual Meeting. Abstr. 898.7). This analysis was limited to embryonic stages, however, because Lama5−/− mutants usually die before embryonic day 17 (Miner et al., 1998). To assess roles of this subunit in later stages of neuromuscular synaptogenesis, we used a conditional allele in which exons 15–21 of the Lama5 gene were flanked by loxP sites (Lama5loxP; Nguyen et al., 2005). Cre-mediated recombination of the loxP sites excises these exons, resulting in a frame-shifted laminin α5 mRNA and a null allele. We mated the conditional mutants to transgenic mice in which regulatory sequences from the human skeletal actin gene drive muscle-specific expression of Cre recombinase (HSA-Cre; Schwander et al., 2003). We refer to the resulting Lama5loxP/loxP; HSA-cre mutants as Lama5M/M mice. Lama5M/M mice were externally normal, fertile, and lived for at least 2 yr.

In wild-type mice, laminin α5 is present throughout the basal lamina of embryonic myotubes. Over the first three postnatal weeks, laminin α5 is lost from extrasynaptic basal lamina and becomes concentrated in synaptic basal lamina (Patton et al., 1997; Fig. 1 E). In Lama5M/M muscle, laminin α5 was barely detectable in extrasynaptic basal lamina at postnatal day 0; it was undetectable at 75% of NMJs at P0 and at 95% of NMJs by P10 (Fig. 1 A and not depicted). The low levels of laminin α5 present at birth may result from slow degradation of laminins inserted before gene deletion (see Cohn et al., 2002). In any case, the absence of laminin α5 from NMJs at later stages indicates that synaptic deposits of this subunit in postnatal muscle are contributed solely by the muscle and not by motor neurons or Schwann cells. Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence indicated that levels of laminins α4 and β2 at the NMJ were unaffected by the absence of laminin α5 (Fig. 1 A and not depicted).

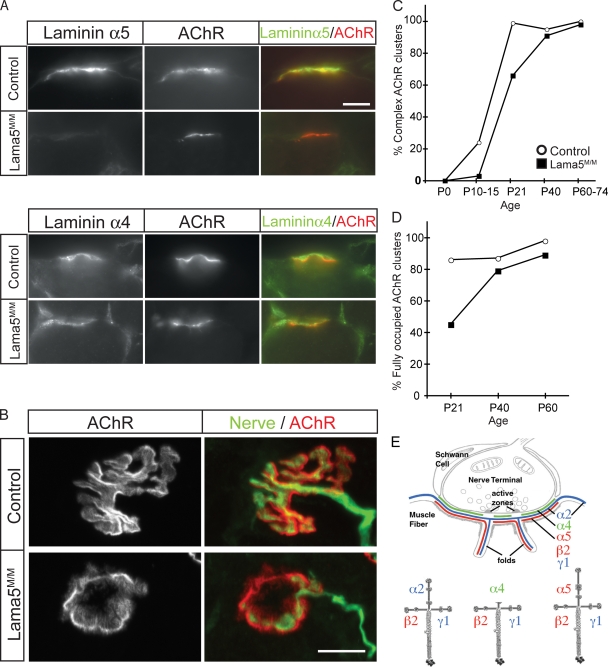

Figure 1.

Muscle-specific deletion of laminin α5 leads to delayed neuromuscular synapse maturation. (A) Laminin α5 protein was undetectable at NMJs by P21 in Lama5M/M mice, but laminin α4 levels were unaltered. Muscle sections were stained with laminin antibodies (green) and Alexa 594–BTX to label AChRs (red). (B) En face views of NMJs in P21 control and Lama5M/M mice stained with antibodies to neurofilaments and SV2 (nerve, green), and Alexa 594–BTX (AChR, red). Motor nerve terminals fully occupied complex AChR clusters in controls. In Lama5M/M muscle, many AChR clusters had a simple morphology and were partially innervated. (C and D) Quantification of topological maturation of AChR clusters (C) and completeness of innervation of AChR clusters (D) in control (open circles) and Lama5M/M (closed squares) sternomastoid muscle. Counts are from two animals per age, >40 NMJs per animal, with the exception of controls at P21 and P40, which are from one animal. (E) Laminin chains present in synaptic BL (adapted from Patton et al., 1997). Bars, 10 μm.

Delayed synaptic maturation in the absence of laminin α5

At birth, postsynaptic AChR clusters at normal NMJs are ovoid plaques; during the first three postnatal weeks, they are transformed to perforated and then C-shaped aggregates, and finally to pretzel-shaped branched arrays (Slater, 1982; Desaki and Uehara, 1987; Marques et al., 2000; Kummer et al., 2004). To examine whether this process requires laminin α5, we stained longitudinal sections of muscles from Lama5M/M mice and littermate controls with fluorescently labeled α-bungarotoxin (BTX), which binds specifically to AChRs. We detected no difference between Lama5M/M and control muscles during the first few postnatal days or in adulthood (Fig. 1 C). Examination of intermediate time points showed, however, that the topological transformation of AChR clusters was delayed in Lama5M/M mice (Fig. 1 B). In sternomastoid muscle, for example, maturation was delayed by >1 wk (Fig. 1 C). Similar results were obtained in diaphragm (unpublished data). Thus, muscle-derived laminin α5 promotes topological maturation of the postsynaptic membrane at the NMJ.

To assess roles of laminin α5 in presynaptic differentiation, we stained Lama5M/M muscle with antibodies to a synaptic vesicle protein (SV2) and an axonal antigen (neurofilament). In control animals, motor nerve terminals were precisely apposed to AChR-rich postsynaptic sites at >80% of NMJs at P21 and >90% of NMJs by P60 (Fig. 1, B and D). In Lama5M/M mice, in contrast, motor nerves only partially covered the postsynaptic membrane of many NMJs between P21 and P40 (Fig. 1, B and D). At later times, however, apposition was achieved in both sternomastoid and diaphragm muscles (Fig. 1 D and not depicted). Thus, pre- as well as postsynaptic differentiation is delayed in Lama5M/M mutants.

A chimeric laminin α chain rescues pre- but not postsynaptic defects in laminin α5 mutants

As synaptic laminins have been implicated in presynaptic differentiation (Noakes et al., 1995; Patton et al., 1997, 1998, 2001; Nishimune et al., 2004), we considered the possibility that defects in postsynaptic maturation in Lama5M/M muscle might be secondary consequences of the presynaptic defects. In an attempt to differentially rescue pre- and postsynaptic phenotypes, we used transgenic mice that ubiquitously express a chimeric laminin subunit in which the C-terminal ∼540 amino acids of α5 are replaced by the homologous sequences from laminin α1 (Kikkawa et al., 2002; Fig. 2 A). This region comprises the terminal three of five laminin globular (LG) domains present in all laminin α chains. LG domains contain binding sites for several transmembrane proteins that bind laminin; some bind differentially to the LG domains in the α1 and α5 chains (Kikkawa and Miner, 2005; Nishiuchi et al., 2006; Kikkawa et al., 2007). The chimera transgene, called Mr5G2, rescues the embryonic lethality of Lama5−/− null mutants: Lama5−/−;Mr5G2 mice are outwardly normal and live for up to several months before succumbing to kidney disease (Kikkawa and Miner, 2006).

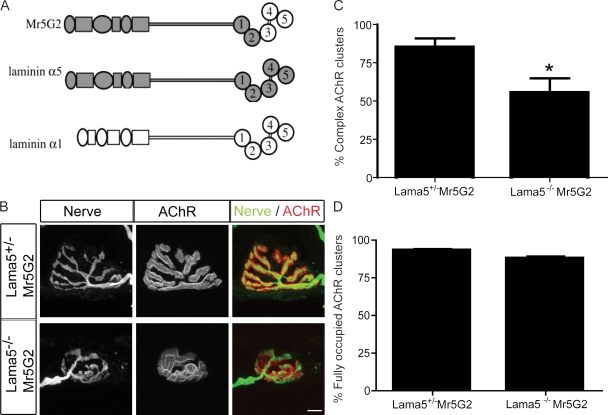

Figure 2.

Chimeric laminin α5 chain rescues the pre- but not postsynaptic phenotype in Lama5 null mice. (A) Structure of the Mr5G2 transgene, in which the C-terminal three LG domains of laminin α5 are replaced by the corresponding domains of laminin α1. (B) NMJs from control (Lama5+/−;Mr5G2) and Lama5−/−;Mr5G2 sternomastoid at P21 stained as in Fig. 1 B. AChR clusters in the mutant are small and immature but fully occupied by motor neuron terminals. Bar, 10 μm. (C and D) Quantification of topological maturation of AChR clusters (C) and completeness of innervation of AChR clusters (D) in control (Lama5+/−;Mr5G2) and Lama5−/−;Mr5G2 muscles. Counts are from sternomastoid and diaphragm muscles of two animals per genotype, >190 NMJ per animal. *, significant by unpaired t test, P < 0.05.

We analyzed Lama5−/−;Mr5G2 mice at P21, when both pre- and postsynaptic differentiation are impaired in Lama5M/M mice. At this age, maturation of the postsynaptic apparatus was as incomplete in Lama5−/−;Mr5G2 muscle as in Lama5M/M muscle (Fig. 2, B and C). In contrast, whereas innervation was incomplete at this age in Lama5M/M muscle, motor axons completely occupied AChR-rich postsynaptic sites in Lama5−/−;Mr5G2 muscle (Fig. 2, B and D). Thus, the Mr5G2 chimera promotes presynaptic maturation effectively but postsynaptic maturation poorly.

We draw three conclusions from the observation that postsynaptic defects persist despite rescue of presynaptic defects by the Mr5G2 transgene. First, postsynaptic defects may result from a direct action of laminin on the postsynaptic apparatus. Second, receptors that mediate the postsynaptic effects of laminin interact differentially with the final three LG domains of laminins α1 and α5. Finally, sites shared by laminins α1 and α5 interact with nerve terminals to promote complete coverage of postsynaptic sites.

Arrested synaptic maturation in muscles lacking laminins α4 and α5

Because synaptic defects in Lama5M/M mice were transient, we considered the possibility that roles of laminin α5 were partially redundant with or compensated by another synaptic cleft component. A likely candidate was laminin α4, the other laminin α chain selectively associated with synaptic basal lamina. Laminin α4 remained concentrated at synapses in Lama5M/M muscle (Fig. 1 A). Targeted mutants lacking laminin α4 (Lama4−/−) are healthy and fertile (Patton et al., 2001), so we were able to test this possibility by generating HSA-Cre;Lama4−/−;Lama5loxP/loxP (Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M) double mutants.

NMJs in Lama4−/− mice are smaller than those in controls and exhibit ultrastructural defects in alignment of specializations in nerve terminals with those in the postsynaptic membrane (Patton et al., 2001). However, maturation of the postsynaptic membrane to a branched array is not perturbed in Lama4−/− mice (Fig. 3 D). Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M double mutants were smaller and weaker than either single mutant (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805095/DC1), and most died around 3 mo of age. During the first two postnatal weeks, NMJs in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice resembled those in Lama5M/M mice. Subsequently, however, although pre- and postsynaptic maturation were delayed in Lama5M/M mice and unaffected in Lama4−/− mice, they were arrested in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mutants. Similar results were seen in sternomastoid, diaphragm, and tibialis anterior muscles (Fig. 3, B, D, and E; Fig. S2; and not depicted). Arrest of the topological transformation from plaque-shaped to branched postsynaptic apparatus was evident using markers of the synaptic cleft (agrin, acetylcholinesterase, and glycoconjugates recognized by the VVA-B4 lectin; Fig. 3 C and not depicted) as well as AChRs.

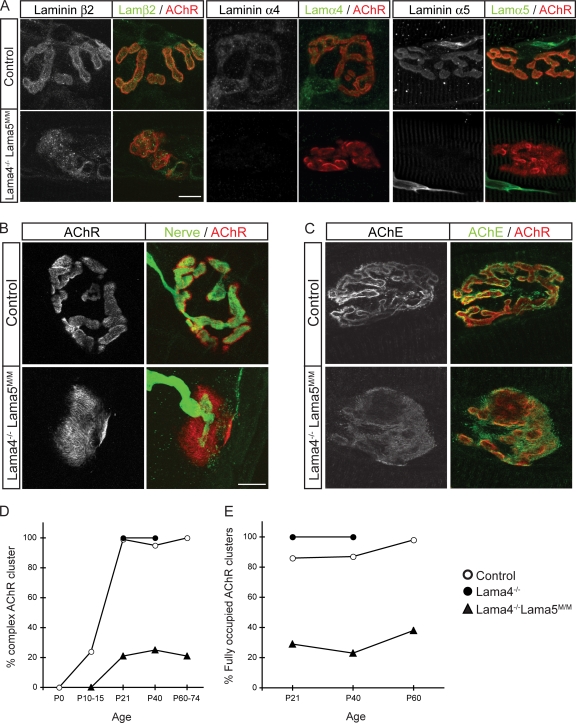

Figure 3.

Arrest of postsynaptic maturation in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice. (A) NMJs from Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice at P36 lack laminins α4 and α5 but retain laminin β2. (B) Most postsynaptic sites retained a simple plaque-like topology and remained only partially occupied by nerve terminals in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice at P60. (C) NMJs from Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice at P36 retained acetylcholinesterase (AChE). Bars, 10 μm. (D and E) Quantification of topological maturation of AChR clusters (D) and completeness of innervation of AChR clusters (E) in control (open circles), Lama4−/− (closed circles), and Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice (closed triangles). Counts are from two animals per age, >40 NMJs per animal.

To ask whether the apparent arrest in postsynaptic maturation resulted from ongoing muscle degeneration and regeneration, we counted central nuclei, a marker of regenerating muscle fibers that persists for several months (Schmalbruch, 1976). The number of central nuclei did not differ significantly between double mutants and controls (unpublished data).

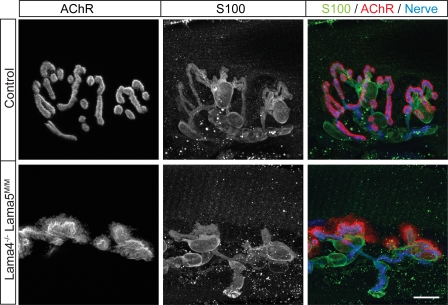

Schwann cells are the third cell of the NMJ. They respond to laminins, and defects in synaptic Schwann cells are evident in mice lacking laminin β2 (Patton et al., 1998). We therefore assessed the distribution of terminal Schwann cells in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice by staining muscles with antibodies to the Schwann cell marker S-100β. In mutants as in controls, Schwann cells capped nerve terminals, and only portions of postsynaptic membrane devoid of nerve terminals lacked Schwann cells (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the abnormal distribution of Schwann cells in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mutants is secondary to presynaptic defects.

Figure 4.

Schwann cells colocalize with motor nerve terminals in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M NMJ. En face view of NMJs from Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M and control mice were stained with antibodies against Schwann cells (S100, green), nerve terminals (neurofilament + SV2, blue), and AChRs (BTX, red). Schwann cells colocalized with the nerve terminal but did not cover the unoccupied AChR clusters in the mutant. Bar, 10 μm.

Previous studies have revealed a prominent role for laminin β2 in maturation of nerve terminals and synaptic Schwann cells (Noakes et al., 1995; Patton et al., 1998; Nishimune et al., 2004). We therefore considered the possibility that loss of laminins α4 and α5 might impair synaptic maturation indirectly by leading to loss of laminin β2. However, laminin β2 immunoreactivity persisted at synaptic sites (Fig. 3 A). Although levels of laminin β2 immunoreactivity varied among NMJs, defects were seen in laminin β2–rich as well as in laminin β2–poor NMJs of Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mutants.

Direct effect of laminins α4 and α5 on myotubes

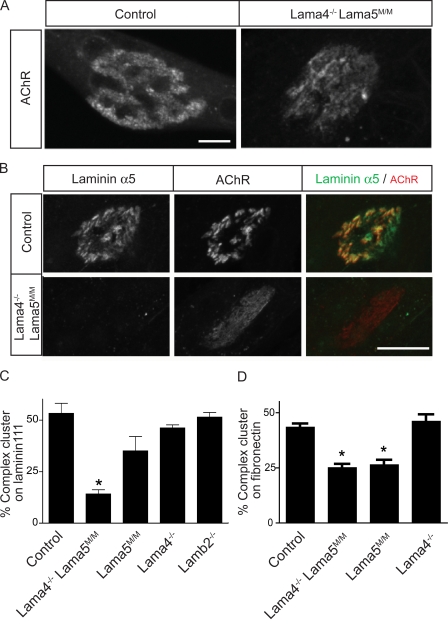

Analysis of Lama5−/−;Mr5G2 mice (Fig. 2) suggested that synaptic laminins exert a direct effect on topological maturation of AChR clusters. For a direct test of this idea, we cultured muscle cells from wild-type and mutant mice in the absence of neurons. We dissociated myoblasts from control and Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice, cultured them on substrates coated with laminin 111, and allowed them to fuse into myotubes. Under these conditions, complex, branched AChR clusters form on the myotube surface that contacts the substrate, and laminin α5 concentrates in apposition to the AChR clusters (Kummer et al., 2004; Fig. 5, A and B). Clusters also formed on Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M myotubes, but the fraction of clusters with a complex morphology after 8 d in vitro was ∼60% lower in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M myotubes than in controls (∼20% vs. ∼50%; Fig. 5, B and C). Thus, Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M myotubes are deficient in their ability to form branched arrays of AChRs. To determine whether these results depended on the presence of a distinct laminin (laminin 111) on the substrate, we also cultured control and Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M muscle cells on fibronectin. Again, the proportion of complex AChR clusters was lower on Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M myotubes than on control (Fig. 5 D).

Figure 5.

Laminins α4 and α5 exert an autocrine effect on postsynaptic maturation. (A) Myotubes from control and Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice were cultured on laminin 111 and stained for AChRs with Alexa 594–BTX. Micrographs show a complex AChR cluster on a control myotube and a simple AChR plaque on a Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M myotube. (B) Laminin α5 is associated with AChR clusters in control myotubes but was absent from clusters in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M. Bars, 10 μm. (C and D) Quantification of AChR aggregate topology on myotubes from control, Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M, Lama5M/M, Lama4−/−, and Lamb2−/− myotubes cultured on laminin 111 (C) or fibronectin (D). Myotubes from lama4−/−;Lama5M/M and lama5M/M mice form fewer complex AChR clusters on both substrates than do control, Lama4−/−, or Lamb2−/− myotubes. For each experiment, at least 150 AChR clusters were examined. Counts show mean ± SEM from three animals per genotype. *, significant by one-way analysis of variance, P < 0.0001.

We also prepared cultures from Lama5M/M, Lama4−/−, and Laminin β2 (Lamb2−/−) single mutant mice. Myotubes from Lama4−/− and Lamb2−/− mice exhibited the same proportion of complex receptor clusters as did controls (Fig. 5 C and D). In contrast, myotubes from Lama5M/M mice showed fewer complex receptor clusters than controls; this difference was not statistically significant in myotubes grown on laminin 111 but was significant in myotubes grown on fibronectin (Figs. 5, C and D). Collectively with observations in vivo, these results suggest that laminin a5 plays a dominant role in postsynaptic maturation but that laminin a4 can partially compensate for its loss. The deficiency in topological maturation was not an indirect consequence of impaired ability to form clusters because soluble agrin induced similar numbers of AChR clusters on primary myotubes prepared from control, Lama5M/M, or Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805095/DC1). These results indicate that laminins α4 and α5 signal directly to myotubes to induce topological maturation of AChR clusters.

Effect of laminin on postsynaptic localization of laminin receptors

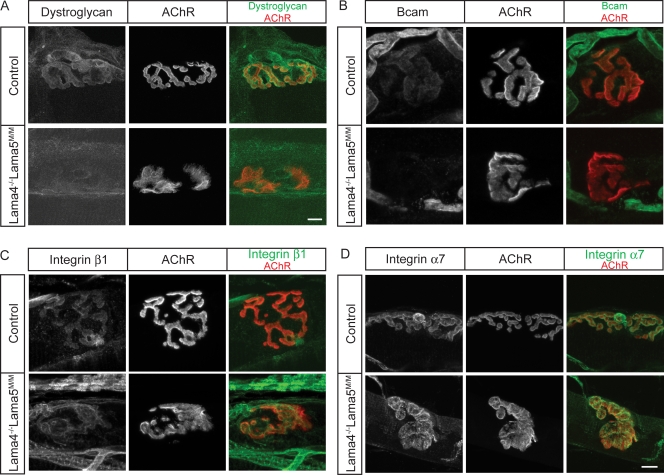

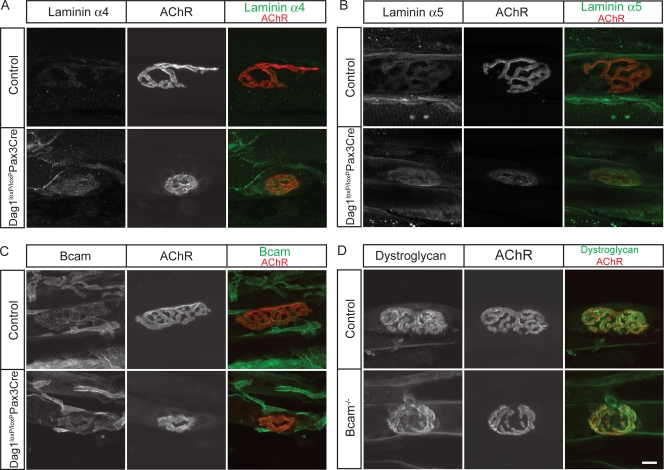

Analysis of the chimeric laminin described above (Mr5G2; Fig. 2) suggested that sites in globular domains LG3-5 of laminin α5 interact with receptors on muscle fibers. Three laminin-binding proteins have been shown to bind to this region: dystroglycan, β1 integrins, and basal cell adhesion molecule/Lutheran blood group antigen (Bcam), an immunoglobulin superfamily adhesion molecule (Belkin and Stepp, 2000; Timpl et al., 2000; Kikkawa and Miner, 2005; Suzuki et al., 2005; Barresi and Campbell, 2006; Nishiuchi et al., 2006). All three receptors are expressed by muscle and present in postsynaptic regions of the muscle fiber membrane (Fig. 6; Matsumura et al., 1992; Martin et al., 1996). They are therefore candidate mediators of the postsynaptic effects of laminins. In several cases, laminins have been shown to promote aggregation of their receptors (Colognato et al., 1999; Moulson et al., 2001; Marangi et al., 2002; Smirnov et al., 2002). As a first test of whether synaptic laminins interact with these receptors, we therefore asked whether their synaptic localization was perturbed in Lama5M/M or Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mutants.

Figure 6.

Distribution of laminin receptors at NMJs of Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice. (A and B) Dystroglycan (A) and Bcam (B) are present at higher levels in synaptic rather than extrasynaptic regions of muscle fibers in control mice. Synaptic levels of both antigens were decreased Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M muscle. (C and D) Integrin β1 (C) and integrin α7 (D) are concentrated at synaptic regions of both control and Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M muscle fibers. Longitudinal sections of sternomastoid at P60–79 muscle were stained with antibodies to laminin receptors (green) and AChRs (red). Bars, 10 μm.

Dystroglycan is present throughout the muscle fiber surface, but it is present at higher levels in the postsynaptic membrane than in extrasynaptic regions (Matsumura et al., 1992; Cohen et al., 1995). The synaptic concentration of dystroglycan persisted in adult Lama5M/M and Lama4−/− muscle but was greatly reduced in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M muscle (Fig. 6 A and not depicted). Extrasynaptic levels of dystroglycan immunoreactivity were not detectably different in Lama5M/M or Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice than in littermate controls.

Bcam is present in the membrane of embryonic myotubes (Moulson et al., 2001). We found that Bcam levels decline in extrasynaptic regions of muscle fibers postnatally but that Bcam immunoreactivity persists at synaptic sites into adulthood (Fig. 6 B). In contrast, Bcam was barely detectable in the synaptic membranes of either Lama5M/M or Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice (Fig. 6 B and not depicted).

Integrins are α/β heterodimers that bind a variety of matrix molecules. Several integrins are receptors for laminins, including α3β1, α6β1, and α7β1. We stained sections of control, Lama4−/−, Lama5M/M, and Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice for the common integrin β1 subunit but saw no difference between controls and any of the mutants; in all cases, integrin β1 was present throughout the muscle fiber membrane, with higher levels in synaptic rather than extrasynaptic regions (Fig. 6 C and not depicted). We also stained muscle for integrin α7, which is known to be concentrated in the postsynaptic membrane (Martin et al., 1996; Burkin and Kaufman, 1999). Again, no differences in level or localization were observed between controls and any of these mutants (Fig. 6 D and not depicted).

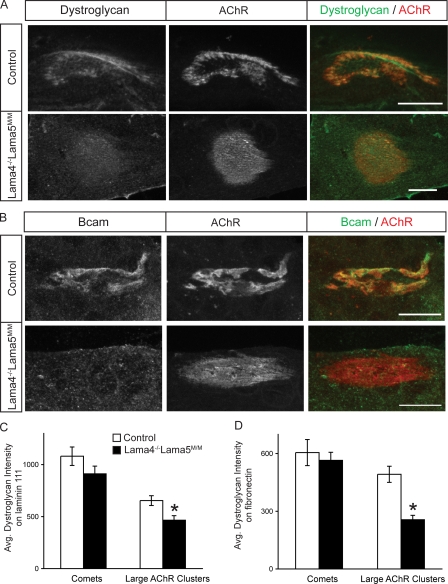

These results are consistent with the idea that interactions of dystroglycan and Bcam with laminin α5, either in conjunction with laminin α4 (dystroglycan) or alone (Bcam), promote aggregation of these receptors in the postsynaptic membrane. Alternatively, however, the absence of specific laminins might influence presynaptic structures, which in turn might be responsible for localizing dystroglycan and Bcam. To distinguish these possibilities, we used the culture system illustrated in Fig. 5. High levels of both dystroglycan and Bcam were associated with AChR clusters in control myotubes (Fig. 7, A and B). In myotubes from Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice, in contrast, levels of dystroglycan were significantly decreased, and levels of Bcam were dramatically decreased at large AChR clusters whether laminin 111 or fibronectin were used for culture substrate (Fig. 7, A–D).

Figure 7.

Decreased dystroglycan and Bcam at AChR clusters lacking laminins α4 and α5. (A and B) Control and Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M cultures were stained for AChR, dystroglycan (A) and Bcam (B). Levels of both antigens are decreased at clusters on mutant myotubes. Bars, 10 μm. (C and D) Dystroglycan relative fluorescence intensity in AChR clusters from control and Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M myotubes cultured on laminin 111 (C) or fibronectin (D). Counts show mean ± SEM from at least three independent cultures, >75 AChR clusters per culture. *, significant by unpaired t test, P < 0.002.

Further analysis of these cultures revealed two additional features of Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M myotubes. First, low levels of laminin α5 persisted at AChR-rich clusters in some mutant myotubes. The residual laminin might have been synthesized by muscle cells before Cre-mediated excision of the Lama5 gene. Second, although levels of dystroglycan were decreased at plaque-shaped and branched AChR clusters in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M myotubes, they remained high in small linear or comet-shaped AChR clusters resembling those formed spontaneously or after application of agrin to myotubes cultured on gelatin (Fig. S4, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805095/DC1). In contrast, levels of Bcam were decreased at all AChR clusters in mutants. This result raises the possibility that initial association of dystroglycan with AChR clusters is laminin independent, whereas maintenance of that association is laminin dependent.

Dystroglycan but not Bcam promotes postsynaptic maturation

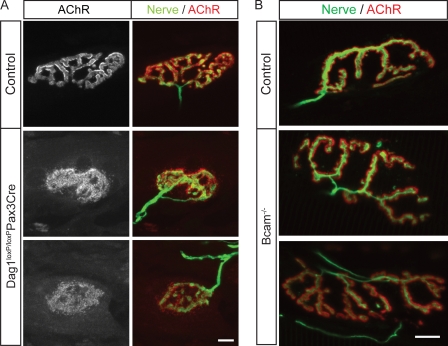

If laminin-dependent aggregation of dystroglycan or Bcam promotes postsynaptic maturation, one would expect that synapses would remain immature in the absence of the critical laminin-binding protein. To test this idea, we analyzed mice lacking dystroglycan or Bcam.

Dystroglycan null mice (Dag1−/−) die early in gestation because of disruption of extraembryonic membranes (Williamson et al., 1997). We therefore used a conditional Dag1 allele (Dag1loxP/loxP; Cohn et al., 2002). These mice were mated to transgenic mice that express Cre recombinase under the control of regulatory elements from the Pax3 gene (Pax3-Cre; Li et al., 2000). Dag1loxP/loxP;Pax3-Cre mice are viable, but dystroglycan is efficiently eliminated from a subset of skeletal muscles, including the tibialis anterior of the hind limb (unpublished data). In tibialis muscle of P24 Dag1loxP/loxP;Pax3-Cre mice, AChR clusters were complex at only 3% of NMJs (Fig. 8 A). The postsynaptic membrane was complex at 97% of control NMJs by this age. Counts of central nuclei (see above) showed that ∼11% of muscle fibers in the tibialis anterior of Dag1loxP/loxP:Pax3-Cre had undergone at least one cycle of degeneration and regeneration by P24 (unpublished data). As postsynaptic maturation was impaired in 97% of muscle fibers, we conclude that the synaptic defects were not an indirect consequence of muscle damage. These results are consistent with those obtained previously in chimeric mice and cultured myotubes (see Discussion). Thus, postsynaptic maturation is arrested in Dag1loxP/loxP;Pax3-Cre mice, as it is in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice. In contrast, nerve terminals fully covered postsynaptic sites in Dag1loxP/loxP;Pax3-Cre mice, whereas, as shown in Fig. 3, innervation was incomplete in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M muscle. These results support the idea that dystroglycan mediates the autocrine effects of laminin on postsynaptic maturation.

Figure 8.

Dystroglycan but not Bcam is required for postsynaptic maturation. (A) AChR clusters in Dag1loxP/loxP;Pax3-Cre mice were plaque-like in topology. (B) NMJs in Bcam−/− mice are indistinguishable in topology from those in littermate controls. Longitudinal sections of adult tibialis muscles were stained with antibodies to neurofilaments and SV2 (nerve, green), and Alexa 594–BTX (AChR, red). Bars, 10 μm.

To assess the role of Bcam at the NMJ, we generated targeted null mutants (see Materials and methods). Bcam−/− mice were viable, fertile and overtly healthy (unpublished data), similar to those described recently (Rahuel et al., 2008). We examined NMJs in the sternomastoid, diaphragm, and tibialis anterior muscles of Bcam−/− mice at both P21 and in adulthood (P49 and P330). In all muscles at both ages, the structure and maturity of NMJs in mutants was indistinguishable from those in littermate controls (Fig. 8 B and not depicted).

Effect of dystroglycan on synaptic localization of laminins

Results presented so far support the idea that laminins α4 or α5 act by concentrating dystroglycan in the postsynaptic membrane, where it can interact with other synaptic components and/or transmit signals to the cell's interior (see Discussion). However, this model would be open to question if dystroglycan were also required for synaptic localization of the laminins, a possibility suggested by studies on myotubes derived from dystroglycan-null embryonic stem cells (Grady et al., 2000). We therefore asked whether dystroglycan is required for the synaptic localization of laminins α4 or α5 in vivo. In fact, levels and patterns of laminin α4, and laminin α5 immunoreactivity were similar at NMJs Dag1loxP/loxP;Pax3-Cre mice and littermate controls (Fig. 9, A and B). Likewise, loss of dystroglycan had no detectable effect on the synaptic levels or distribution of integrin α7, integrin β1, or Bcam, and patterns of laminin α4, laminin α5, integrin α7, integrin β1, and dystroglycan did not differ detectably between Bcam−/− mice and controls (Fig. 9, C and D; and unpublished data). The synaptic concentration of laminins at NMJs in Dag1loxP/loxP:Pax3-Cre muscle suggests that whereas synaptic laminin α chains are required to localize dystroglycan, the opposite is not true.

Figure 9.

Roles of dystroglycan in localizing synaptic laminins and Bcam. (A–C) Laminin α4, laminin α5, and Bcam are similarly concentrated at synaptic sites of control and Dag1loxP/loxP:Pax3-Cre muscles. (D) Dystroglycan is similarly concentrated at synaptic sites of control and Bcam−/− muscles. Bar, 10 μm.

Discussion

As the NMJ forms, AChRs cluster in the postsynaptic membrane. Early steps in postsynaptic differentiation have been studied in detail and are known to involve interplay of nerve-derived signals and muscle cell–autonomous programs (for review see Kummer et al., 2006). In contrast, little is known about factors that control the subsequent molecular and topological changes that occur as the NMJ matures. Here, we have focused on roles of laminins in the postnatal transformation of the NMJ from a simple plaque to a complex branched array. We analyzed NMJs in a set of five targeted null and conditional mutants, as well as in myotubes cultured aneurally from several of the lines. Collectively with previous studies (see Introduction), our results lead to three major conclusions: (1) laminins containing the α4 and α5 subunits are muscle-derived autocrine promoters of postsynaptic differentiation; (2) these autocrine effects depend in large part on the ability of laminins α4 and α5 in the synaptic cleft to aggregate dystroglycan in the postsynaptic membrane; and (3) the three synaptically concentrated laminin subunits (α4, α5, and β2) play distinct but interrelated roles in both pre- and postsynaptic differentiation.

Laminins as autocrine synaptic organizing molecules

Pre- and postsynaptic differentiation are interdependent (Sanes and Lichtman, 1999, 2001). Therefore, in considering roles of laminins α4 and α5 in postsynaptic maturation, a main issue is the relationship between their cellular source and target. Three possibilities, which are not mutually exclusive, are: (a) laminins α4 and α5 might be synthesized by nerve or Schwann cells and act transsynaptically on muscle cells; (b) they might be synthesized by muscle and act transsynaptically to affect presynaptic differentiation, with postsynaptic defects being indirect consequences of the presynaptic impairment; and (c) they might both be synthesized by and act directly on the postsynaptic cell.

Several results favor the third of these alternatives, that laminin acts by an autocrine mechanism. First, laminins α4 and α5 are made by myotubes and inserted into basal lamina associated with postsynaptic specializations (Patton, 2000). Second, laminins α4 and α5 are not detectably expressed by motor neurons (Miner et al., 1997). Third, the use of a conditional Lama5 mutant allowed us to excise laminin selectively from muscle cells, leaving other potential sources unperturbed. Postsynaptic maturation was delayed in these mice and arrested in mice that also lacked laminin α4. Fourth, myotubes from Lama5M/M;Lama4−/− mice cultured in the absence of neurons displayed defects in AChR aggregation. Thus, although laminins also act on nerve terminals, their effects on postsynaptic maturation are in large part direct.

Several groups have shown previously that application of laminin to cultured myotubes promotes formation of AChR clusters (Vogel et al., 1983; Sugiyama et al., 1997; Montanaro et al., 1998; Smirnov et al., 2002; Marangi et al., 2002). The relationship of this effect to synapse formation in vivo has been unclear, however, because the laminin isoforms used in vitro (laminins 111 and 211) are not found in synaptic basal lamina. Moreover, the effects of soluble laminin in vitro occur in the absence of the receptor tyrosine kinase muscle-specific kinase (MuSK), whereas no AChR clusters form on laminin-laden MuSK−/− myotubes in vivo (e.g., Lin et al., 2001). We have shown that substrate-bound laminin 111 promotes AChR aggregation by a MuSK-dependent mechanism (Kummer et al., 2004) and now show that α4- and α5-containing laminins (421 and 521) are more potent or different from laminin 111.

Dystroglycan as a synaptic laminin receptor

If laminins are autocrine promoters of postsynaptic differentiation, they presumably act through receptors on myotubes. Laminins are large multisubunit proteins, and at least a dozen laminin-binding moieties (proteins and carbohydrates) have been described, many of which are present in muscle (Suzuki, et al., 2005). As one way of narrowing the set of candidates, we took note of the finding that a chimeric laminin, Mr5G2, failed to rescue postsynaptic defects on Lama5−/− mice (Fig. 2). Because this chimera differs from laminin α5 only in its last three LG domains, we hypothesized that mediators of the effects of laminin on postsynaptic membrane would not only be present in the postsynaptic membrane but also interact with the C-terminal three LG domains of laminin α5. Three receptors that meet these criteria are dystroglycan, Bcam, and β1 integrins. Of these, our analysis supports a critical role for dystroglycan.

Dystroglycan was discovered as a laminin-binding protein (Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya et al., 1992; Gee et al., 1993; Barresi and Campbell, 2006), but it was initially implicated in NMJ formation when it was discovered that it also binds agrin, a nerve-derived organizer of postsynaptic differentiation (Bowe et al., 1994; Campanelli et al., 1994; Gee et al., 1994). Later studies showed that agrin does not signal through dystroglycan (Sanes and Lichtman 2001). In parallel, however, evidence accumulated favoring the idea that dystroglycan and other proteins of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex (Grady et al., 1997, 2000) are involved in later aspects of postsynaptic maturation. For example, NMJs in chimeric mice generated from dystroglycan null embryonic stem (ES) cells have a simplified postsynaptic topology (Côté et al., 1999), and cultured myotubes generated directly from such ES cells form abnormal AChR clusters (Grady, et al., 2000; Jacobson et al., 2001). Here, we used conditional dystroglycan mutants to generate mice in which dystroglycan is uniformly deleted from a subset of muscles (Dag1loxP/loxP;Pax3-Cre; unpublished data). We were therefore able to directly compare synaptic morphology in the absence of laminins α4 and α5 and in the absence of dystroglycan. The similar postsynaptic phenotypes in these two mutants supports the idea that dystroglycan mediates the effects of synaptic laminins on postsynaptic differentiation.

Further studies suggest that laminins may act by promoting aggregation of dystroglycan in the postsynaptic membrane, where it can transduce signals or recruit other components. For example, levels of dystroglycan immunoreactivity associated with AChR clusters were markedly reduced in the postsynaptic membrane of Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice and in myotubes cultured aneurally from these mice. Moreover, loss of dystroglycan was not evident at NMJs from Lama4−/− or Lama5M/M single mutants, in which postsynaptic differentiation was normal or only delayed, respectively. Conversely, laminins α4 and α5 remained concentrated at synaptic sites in dystroglycan-deficient muscle, which indicates that, in vivo, it is laminins that localize dystroglycan rather than vice versa. Together with previous studies showing that soluble laminins can cluster dystroglycan when added to cultured myotubes (Cohen et al., 1997; Montanaro et al., 1998), our results suggest that laminins are responsible, at least in part, for the synaptic concentration of dystroglycans.

How do laminins α4 and α5 aggregate dystroglycan? The answer is not straightforward, in that dystroglycan also binds laminin α2, which is present throughout the muscle fiber membrane (Fig. 1 E), and laminin α1, which is used as uniform substrate in myotube cultures (Kummer et al., 2004). The simplest possibility is that laminins α4 and α5 bind differently or more tightly to dystroglycan than do laminins α1 and α2. Unfortunately, there is currently no evidence to support this idea, and pure, intact laminin chains are not available to test it. Alternatively, laminins α4 and α5 might recruit linker proteins that aggregate dystroglycan. We have not rigorously tested this possibility but provide evidence that if such linkers do exist, they do not include the laminin- or dystroglycan-binding proteins agrin, integrin α7β1, or Bcam.

How, in turn, might clustered dystroglycan promote postsynaptic maturation? First, one possibility is that it interacts with AChRs to maintain their high density. Indeed, dystroglycan binds to rapsyn, which in turn clusters AChRs, and to MuSK, a component of the primary postsynaptic scaffold (Apel et al., 1995, 1997; Bartoli et al., 2001). Second, dystroglycan is a key component of a dystrophin glycoprotein complex, several intracellular components of which have been implicated in postsynaptic maturation (Deconinck et al., 1997; Grady et al., 1997, 2000, 2003, 2006; Bogdanik et al., 2008). Third, dystroglycan might interact with other laminin receptors such as integrins or Bcam. Our results indicate that Bcam is unlikely to be involved, but we were unable to directly test the role of β1 integrins for the postnatal NMJ maturation because deletion of the β1 integrin gene from muscle cells leads to embryonic lethality (Schwander et al., 2003, 2004). However, mice lacking integrin α7, the main synaptic laminin-binding integrin, were found to show no morphological abnormalities at the NMJ (Mayer et al., 1997).

Laminins as transsynaptic coordinators

The laminin α4, α5, and β2 chains are selectively associated with the basal lamina of the synaptic cleft (Fig. 1 E; Sanes et al., 1990; Patton et al., 1997). Previous studies showed that β2 laminins serve as critical organizers of presynaptic maturation (Noakes et al., 1995; Knight et al., 2003; Nishimune et al., 2004) and also affect placement of terminal Schwann cells (Patton et al., 1998). Laminin α4 helps to specify the precise apposition of pre-to-postsynaptic specializations (Patton et al., 2001). Here, we focused on the third synaptically concentrated laminin chain, α5, and discovered new roles of laminins in synaptic maturation. First, analysis of laminin α5 conditional mutants (Lama5M/M) showed that α5 is an autocrine promoter of postsynaptic differentiation. Second, analysis of Lama5−/−;Mr5G2 mice showed that laminin α5 acts through a distinct mechanism to ensure complete innervation of the postsynaptic membrane. Third, analysis of Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M double mutants showed that α4 can substitute for α5, at least in regard to its postsynaptic activity. Together, these results show that synaptic laminins act collaboratively on all three cells of the NMJ to organize and coordinate synaptic maturation.

Materials and methods

Animals

The generation of the following genetically engineered mouse strains has been described previously: Lama5 null (Miner et al., 1998), Lama5loxP conditional mutant (Nguyen et al., 2005), Lama4 null (Patton et al., 2001), Lamb2 null (Noakes et al., 1995), Dag1loxP conditional mutant (Cohn et al., 2002), Mr5G2 transgenic mice (Kikkawa et al., 2003; Kikkawa and Miner, 2006), HSA-Cre transgenic mice (Schwander et al., 2003), and Pax3Cre transgenic mice (Li et al., 2000). Generation of Bcam/Lutheran null mice was performed by homologous recombination in R1 embryonic stem cells. In brief, the engineered Bcam mutation deletes 2 kb of genomic DNA containing exons 11–13 (of 15 total). This segment encodes 142 aa comprising the fifth Ig-like domain, the transmembrane domain, and the first 20 aa of the cytoplasmic tail, so a functional receptor cannot be produced. In addition, splicing from exon 10 to 14 results in an out-of-frame mRNA, and antibodies to either the extracellular or the intracellular domain of Bcan fail to stain Bcam−/− mouse tissues (Fig. S5, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805095/DC1). All animal studies have been approved by the authors' institutional review boards.

Histological analysis

Primary antibodies were as follows: anti-agrin (AGR-131; Assay Designs), anti-acetylcholinesterase (gift of T. Rosenberry, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Jacksonville, FL), anti–β-dystroglycan (43DAG1/8D5; and 7D11; Novocastra Laboratories, Ltd., and Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, respectively), anti–mouse integrin α7 (3C12; Medical and Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd.), anti–mouse β1 integrin (MAb1997; Millipore), anti–laminin α5 (Miner et al., 1997), anti–laminin α4, anti-Bcam/Lutheran, anti–laminin β2 (rabbit polyclonal antibodies; gifts from T. Sasaki, Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR; and the late R. Timpl, Max-Planck-Institut für Biochemie, Martinsried, Germany; Talts et al., 2000; Sasaki et al., 2002), anti-neurofilament (SMI312; Covance), anti-S100 (polyclonal rabbit; Dako), anti-SV2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), Alexa 488–conjugated secondary antibodies, and Alexa 594–conjugated BTX (Alexa 594–BTX; Invitrogen).

Methods for immunohistochemical analysis have been described previously (Kummer et al., 2004; Nishimune et al., 2004). In brief, muscles were fixed in 4% PFA/PBS, sunk in 20% sucrose/PBS, frozen, and cut in a cryostat. Longitudinal sections were cut at 30 μm and cross sections were cut at 20 μm. Sections were stained sequentially with primary antibodies and a mixture of Alexa 488–conjugated secondary antibody and Alexa 594–BTX, then mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Confocal stacks of 0.5-μm serial sections were obtained using Fluoview1000 (with Plan Apo 100×, 1.45 NA or 40×, 1.3 NA objective lenses; all from Olympus) or C1Si (Plan Apo 60×, 1.40 NA objective lens; both from Nikon) microscopes. Maximal projection and intensity analysis were performed with Metamorph software (MDS Analytical Technologies). Whole images were level-adjusted, combined to generate color images, and cropped in Photoshop (Adobe). The NMJ was judged as fully occupied when the AChR cluster area did not exceed that of the nerve terminal by more than half the diameter of the axon.

Tissue culture

Primary myotubes were cultured, and morphometric analysis of AChR on cultured myotubes was performed as described previously (Kummer et al., 2004). In brief, limb muscles were dissected from P2-3 mouse, dissociated by trypsin digest and trituration, and cultured on laminin 111 or fibronectin. After 2 d in culture, medium was replaced with reduced serum medium (DME, 5% horse serum, and 10 μM TTX [Sigma-Aldrich]) and fed fresh medium after 3 d. After 8–10 d in vitro, cells were fixed and stained overnight at 4°C with Alexa 488–labeled BTX, mouse anti–α-dystroglycan (MANDAG2 clone 7D11; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) and rabbit anti–laminin α5 (Miner et al., 1997). Images were collected on a laser scanning confocal microscope (FV1000; Olympus). Plaque and complex AChR clusters were classified as described previously (Kummer et al., 2004) and grouped as follows: plaque-shaped, simple; and perforated/C-shaped/branched, complex. In some cases, recombinant rat agrin (R & D Systems) was added at the final concentration of 2.4 ng/ml to the primary myotubes on the sixth day after switching to the reduced serum medium, and incubated for 11 h in the 37°C CO2 incubator. Microscopes and objectives were as described in the previous section. To determine dystroglycan levels exclusively at AChR clusters, 1-μm serial sections were collected and the stacks were maximally projected using Metamorph software. BTX-rich areas were traced, and the traced region was superimposed on the dystroglycan channel. For each image, the mean extrasynaptic fluorescence was used for background correction.

Evaluation of muscle strength

Muscle strength was evaluated using an inverted screen test (Contet et al., 2001; Cossins et al., 2004). In brief, each mouse was placed in the center of a screen of wire mesh consisting of 1-mm-diameter wires. Then, the screen was smoothly inverted and held ∼40 cm above a soft surface. The time until the mouse dropped from the screen was measured. Trials were terminated after 90 s. Each mouse was given five trials.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows motor impairment of Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice on the inverted screen test. Fig. S2 shows arrest of postsynaptic maturation in Lama4−/−;Lama5M/M mice. Fig. S3 shows that agrin induces AChR clusters on primary myotubes of laminin mutants. Fig. S4 shows small “comet-shaped” AChR clusters in primary muscle cultures. Fig. S5 shows that Bcam staining is absent from NMJs of Bcam null mutant mice. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805095/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bruce Patton and Terrence Kummer for help and advice, and Takako Sasaki and the late Rupert Timpl for antibodies. The monoclonal antibodies 7D11 and SV2 developed by Drs. G.E. Morris and K.M. Buckley, respectively, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant NS019195 and NS059853 to J.R. Sanes), the National Center for Research Resources (grants P20RR016475 and P20RR024214 to H. Nishimune), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant HD02528 to H. Nishimune), the National Institutes of Health (grants NS046456 and MH078833 to U. Müller), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grants R01DK064687 and R01GM060432 to J.H. Miner), and the American Heart Association (grant 0340090N to J.H. Miner). The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations used in this paper: AChR, acetylcholine receptor; Bcam, basal cell adhesion molecule/Lutheran blood group antigen; BTX, α-bungarotoxin; LG, laminin globular; MuSK, muscle-specific kinase; NMJ, neuromuscular junction.

References

- Apel, E.D., S.L. Roberds, K.P. Campbell, and J.P. Merlie. 1995. Rapsyn may function as a link between the acetylcholine receptor and the agrin-binding dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex. Neuron. 15:115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel, E.D., D.J. Glass, L.M. Moscoso, G.D. Yancopoulos, and J.R. Sanes. 1997. Rapsyn is required for MuSK signaling and recruits synaptic components to a MuSK-containing scaffold. Neuron. 18:623–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley, M., L. Bruckner-Tuderman, W.G. Carter, R. Deutzmann, D. Edgar, P. Ekblom, J. Engel, E. Engvall, E. Hohenester, J.C. Jones, et al. 2005. A simplified laminin nomenclature. Matrix Biol. 24:326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barresi, R., and K.P. Campbell. 2006. Dystroglycan: from biosynthesis to pathogenesis of human disease. J. Cell Sci. 119:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli, M., M.K. Ramarao, and J.B. Cohen. 2001. Interactions of the Rapsyn RING-H2 domain with dystroglycan. J. Biol. Chem. 276:24911–24917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkin, A.M., and M.A. Stepp. 2000. Integrins as receptors for laminins. Microsc. Res. Tech. 51:280–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanik, L., B. Framery, A. Frolich, B. Franco, D. Mornet, J. Bockaert, S.J. Sigrist, Y. Grau, and M.L. Parmentier. 2008. Muscle dystroglycan organizes the postsynapse and regulates presynaptic neurotransmitter release at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. PLoS ONE. 3:e2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowe, M.A., K.A. Deyst, J.D. Leszyk, and J.R. Fallon. 1994. Identification and purification of an agrin receptor from Torpedo postsynaptic membranes: a heteromeric complex related to the dystroglycans. Neuron. 12:1173–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, R.W., Q.T. Nguyen, Y.J. Son, J.W. Lichtman, and J.R. Sanes. 1999. Alternatively spliced isoforms of nerve- and muscle-derived agrin: their roles at the neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 23:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkin, D.J., and S.J. Kaufman. 1999. The alpha7beta1 integrin in muscle development and disease. Cell Tissue Res. 296:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanelli, J.T., S.L. Roberds, K.P. Campbell, and R.H. Scheller. 1994. A role for dystrophin-associated glycoproteins and utrophin in agrin-induced AChR clustering. Cell. 77:663–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.W., C. Jacobson, E.W. Godfrey, K.P. Campbell, and S. Carbonetto. 1995. Distribution of α-dystroglycan during embryonic nerve-muscle synaptogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 129:1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.W., C. Jacobson, P.D. Yurchenco, G.E. Morris, and S. Carbonetto. 1997. Laminin-induced clustering of dystroglycan on embryonic muscle cells: comparison with agrin-induced clustering. J. Cell Biol. 136:1047–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, R.D., M.D. Henry, D.E. Michele, R. Barresi, F. Saito, S.A. Moore, J.D. Flanagan, M.W. Skwarchuk, M.E. Robbins, J.R. Mendell, et al. 2002. Disruption of DAG1 in differentiated skeletal muscle reveals a role for dystroglycan in muscle regeneration. Cell. 110:639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato, H., D.A. Winkelmann, and P.D. Yurchenco. 1999. Laminin polymerization induces a receptor-cytoskeleton network. J. Cell Biol. 145:619–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contet, C., J.N. Rawlins, and R.M. Deacon. 2001. A comparison of 129S2/SvHsd and C57BL/6JOlaHsd mice on a test battery assessing sensorimotor, affective and cognitive behaviours: implications for the study of genetically modified mice. Behav. Brain Res. 124:33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossins, J., R. Webster, S. Maxwell, G. Burke, A. Vincent, and D. Beeson. 2004. A mouse model of AChR deficiency syndrome with a phenotype reflecting the human condition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13:2947–2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté, P.D., H. Moukhles, M. Lindenbaum, and S. Carbonetto. 1999. Chimaeric mice deficient in dystroglycans develop muscular dystrophy and have disrupted myoneural synapses. Nat. Genet. 23:338–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deconinck, A.E., J.A. Rafael, J.A. Skinner, S.C. Brown, A.C. Potter, L. Metzinger, D.J. Watt, J.G. Dickson, J.M. Tinsley, and K.E. Davies. 1997. Utrophin-dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 90:717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desaki, J., and Y. Uehara. 1987. Formation and maturation of subneural apparatuses at neuromuscular junctions in postnatal rats: a scanning and transmission electron microscopical study. Dev. Biol. 119:390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desaki, J., S. Matsuda, and M. Sakanaka. 1995. Morphological changes of neuromuscular junctions in the dystrophic (dy) mouse: a scanning and transmission electron microscopic study. J. Electron Microsc. (Tokyo). 44:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan-Steet, H., M.A. Fox, D. Meyer, and J.R. Sanes. 2005. Neuromuscular synapses can form in vivo by incorporation of initially aneural postsynaptic specializations. Development. 132:4471–4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, M., P.G. Noakes, L. Moscoso, F. Rupp, R.H. Scheller, J.P. Merlie, and J.R. Sanes. 1996. Defective neuromuscular synaptogenesis in agrin-deficient mutant mice. Cell. 85:525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee, S.H., R.W. Blacher, P.J. Douville, P.R. Provost, P.D. Yurchenco, and S. Carbonetto. 1993. Laminin-binding protein 120 from brain is closely related to the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein, dystroglycan, and binds with high affinity to the major heparin binding domain of laminin. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14972–14980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee, S.H., F. Montanaro, M.H. Lindenbaum, and S. Carbonetto. 1994. Dystroglycan-[alpha], a dystrophin-associated glycoprotein, is a functional agrin receptor. Cell. 77:675–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, R.M., H. Teng, M.C. Nichol, J.C. Cunningham, R.S. Wilkinson, and J.R. Sanes. 1997. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 90:729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, R.M., H. Zhou, J.M. Cunningham, M.D. Henry, K.P. Campbell, and J.R. Sanes. 2000. Maturation and maintenance of the neuromuscular synapse: genetic evidence for roles of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex. Neuron. 25:279–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, R.M., M. Akaaboune, A.L. Cohen, M.M. Maimone, J.W. Lichtman, and J.R. Sanes. 2003. Tyrosine-phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated isoforms of alpha-dystrobrevin: roles in skeletal muscle and its neuromuscular and myotendinous junctions. J. Cell Biol. 160:741–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, R.M., D.F. Wozniak, K.K. Ohlemiller, and J.R. Sanes. 2006. Cerebellar synaptic defects and abnormal motor behavior in mice lacking alpha- and beta-dystrobrevin. J. Neurosci. 26:2841–2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya, O., J.M. Ervasti, C.J. Leveille, C.A. Slaughter, S.W. Sernett, and K.P. Campbell. 1992. Primary structure of dystrophin-associated glycoproteins linking dystrophin to the extracellular matrix. Nature. 355:696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, C., P.D. Cote, S.G. Rossi, R.L. Rotundo, and S. Carbonetto. 2001. The dystroglycan complex is necessary for stabilization of acetylcholine receptor clusters at neuromuscular junctions and formation of the synaptic basement membrane. J. Cell Biol. 152:435–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa, Y., and J.H. Miner. 2005. Review: Lutheran/B-CAM: a laminin receptor on red blood cells and in various tissues. Connect. Tissue Res. 46:193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa, Y., and J.H. Miner. 2006. Molecular dissection of laminin alpha 5 in vivo reveals separable domain-specific roles in embryonic development and kidney function. Dev. Biol. 296:265–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa, Y., C.L. Moulson, I. Virtanen, and J.H. Miner. 2002. Identification of the binding site for the Lutheran blood group glycoprotein on laminin alpha 5 through expression of chimeric laminin chains in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 277:44864–44869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa, Y., I. Virtanen, and J.H. Miner. 2003. Mesangial cells organize the glomerular capillaries by adhering to the G domain of laminin α5 in the glomerular basement membrane. J. Cell Biol. 161:187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa, Y., T. Sasaki, M.T. Nguyen, M. Nomizu, T. Mitaka, and J.H. Miner. 2007. The LG1-3 tandem of laminin alpha5 harbors the binding sites of Lutheran/basal cell adhesion molecule and alpha3beta1/alpha6beta1 integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 282:14853–14860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, D., L.K. Tolley, D.K. Kim, N.A. Lavidis, and P.G. Noakes. 2003. Functional analysis of neurotransmission at beta2-laminin deficient terminals. J. Physiol. 546:789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer, T.T., T. Misgeld, J.W. Lichtman, and J.R. Sanes. 2004. Nerve-independent formation of a topologically complex postsynaptic apparatus. J. Cell Biol. 164:1077–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer, T.T., T. Misgeld, and J.R. Sanes. 2006. Assembly of the postsynaptic membrane at the neuromuscular junction: paradigm lost. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16:74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law, P.K., A. Saito, and S. Fleischer. 1983. Ultrastructural changes in muscle and motor end-plate of the dystrophic mouse. Exp. Neurol. 80:361–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., F. Chen, and J.A. Epstein. 2000. Neural crest expression of Cre recombinase directed by the proximal Pax3 promoter in transgenic mice. Genesis. 26:162–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W., R.W. Burgess, B. Dominguez, S.L. Pfaff, J.R. Sanes, and K.-F. Lee. 2001. Distinct roles of nerve and muscle in postsynaptic differentiation of the neuromuscular synapse. Nature. 410:1057–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W., B. Dominguez, J. Yang, P. Aryal, E.P. Brandon, F.H. Gage, and K.-F. Lee. 2005. Neurotransmitter acetylcholine negatively regulates neuromuscular synapse formation by a Cdk5-dependent mechanism. Neuron. 46:569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S., L. Landmann, M.A. Ruegg, and H.R. Brenner. 2008. The role of nerve- versus muscle-derived factors in mammalian neuromuscular junction formation. J. Neurosci. 28:3333–3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marangi, P.A., S.T. Wieland, and C. Fuhrer. 2002. Laminin-1 redistributes postsynaptic proteins and requires rapsyn, tyrosine phosphorylation, and Src and Fyn to stably cluster acetylcholine receptors. J. Cell Biol. 157:883–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques, M.J., J.A. Conchello, and J.W. Lichtman. 2000. From plaque to pretzel: fold formation and acetylcholine receptor loss at the developing neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 20:3663–3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.T., S.J. Kaufman, R.H. Kramer, and J.R. Sanes. 1996. Synaptic integrins in developing, adult, and mutant muscle: selective association of alpha1, alpha7A, and alpha7B integrins with the neuromuscular junction. Dev. Biol. 174:125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura, K., J.M. Ervasti, K. Ohlendieck, S.D. Kahl, and K.P. Campbell. 1992. Association of dystrophin-related protein with dystrophin-associated proteins in mdx mouse muscle. Nature. 360:588–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, U., G. Saher, R. Fassler, A. Bornemann, F. Echtermeyer, H. von der Mark, N. Miosge, E. Poschl, and K. von der Mark. 1997. Absence of integrin alpha 7 causes a novel form of muscular dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 17:318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner, J.H., B.L. Patton, S.I. Lentz, D.J. Gilbert, W.D. Snider, N.A. Jenkins, N.G. Copeland, and J.R. Sanes. 1997. The laminin α chains: expression, developmental transitions, and chromosomal locations of α1-5, identification of heterotrimeric laminins 8-11, and cloning of a novel α3 isoform. J. Cell Biol. 137:685–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner, J.H., J. Cunningham, and J.R. Sanes. 1998. Roles for laminin in embryogenesis: exencephaly, syndactyly, and placentopathy in mice lacking the laminin α5 chain. J. Cell Biol. 143:1713–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misgeld, T., T.T. Kummer, J.W. Lichtman, and J.R. Sanes. 2005. Agrin promotes synaptic differentiation by counteracting an inhibitory effect of neurotransmitter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:11088–11093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanaro, F., S.H. Gee, C. Jacobson, M.H. Lindenbaum, S.C. Froehner, and S. Carbonetto. 1998. Laminin and alpha-dystroglycan mediate acetylcholine receptor aggregation via a MuSK-independent pathway. J. Neurosci. 18:1250–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulson, C.L., C. Li, and J.H. Miner. 2001. Localization of Lutheran, a novel laminin receptor, in normal, knockout, and transgenic mice suggests an interaction with laminin α5 in vivo. Dev. Dyn. 222:101–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.M., D.G. Kelley, J.A. Schlueter, M.J. Meyer, R.M. Senior, and J.H. Miner. 2005. Epithelial laminin alpha5 is necessary for distal epithelial cell maturation, VEGF production, and alveolization in the developing murine lung. Dev. Biol. 282:111–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimune, H., J.R. Sanes, and S.S. Carlson. 2004. A synaptic laminin-calcium channel interaction organizes active zones in motor nerve terminals. Nature. 432:580–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiuchi, R., J. Takagi, M. Hayashi, H. Ido, Y. Yagi, N. Sanzen, T. Tsuji, M. Yamada, and K. Sekiguchi. 2006. Ligand-binding specificities of laminin-binding integrins: a comprehensive survey of laminin-integrin interactions using recombinant alpha3beta1, alpha6beta1, alpha7beta1 and alpha6beta4 integrins. Matrix Biol. 25:189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noakes, P.G., M. Gautam, J. Mudd, J.R. Sanes, and J.P. Merlie. 1995. Aberrant differentiation of neuromuscular junctions in mice lacking s-laminin/laminin beta 2. Nature. 374:258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzer, J.A., Y. Song, and R.J. Balice-Gordon. 2006. In vivo imaging of preferential motor axon outgrowth to and synaptogenesis at prepatterned acetylcholine receptor clusters in embryonic zebrafish skeletal muscle. J. Neurosci. 26:934–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, B.L. 2000. Laminins of the neuromuscular system. Microsc. Res. Tech. 51:247–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, B.L., J.H. Miner, A.Y. Chiu, and J.R. Sanes. 1997. Distribution and function of laminins in the neuromuscular system of developing, adult, and mutant mice. J. Cell Biol. 139:1507–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, B.L., A.Y. Chiu, and J.R. Sanes. 1998. Synaptic laminin prevents glial entry into the synaptic cleft. Nature. 393:698–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, B.L., J.M. Cunningham, J. Thyboll, J. Kortesmaa, H. Westerblad, L. Edstrom, K. Tryggvason, and J.R. Sanes. 2001. Properly formed but improperly localized synaptic specializations in the absence of laminin alpha4. Nat. Neurosci. 4:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahuel, C., A. Filipe, L. Ritie, W. El Nemer, N. Patey-Mariaud, D. Eladari, J.P. Cartron, P. Simon-Assmann, C. Le Van Kim, and Y. Colin. 2008. Genetic inactivation of the laminin alpha5 chain receptor Lu/BCAM leads to kidney and intestinal abnormalities in the mouse. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 294:F393–F406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes, J.R., and J.W. Lichtman. 1999. Development of the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 22:389–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes, J.R., and J.W. Lichtman. 2001. Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2:791–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes, J.R., E. Engvall, R. Butkowski, and D.D. Hunter. 1990. Molecular heterogeneity of basal laminae: isoforms of laminin and collagen IV at the neuromuscular junction and elsewhere. J. Cell Biol. 111:1685–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, T., K. Mann, J.H. Miner, N. Miosge, and R. Timpl. 2002. Domain IV of mouse laminin beta1 and beta2 chains. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:431–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmalbruch, H. 1976. The morphology of regeneration of skeletal muscles in the rat. Tissue Cell. 8:673–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwander, M., M. Leu, M. Stumm, O.M. Dorchies, U.T. Ruegg, J. Schittny, and U. Muller. 2003. Beta1 integrins regulate myoblast fusion and sarcomere assembly. Dev. Cell. 4:673–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwander, M., R. Shirasaki, S.L. Pfaff, and U. Muller. 2004. Beta1 integrins in muscle, but not in motor neurons, are required for skeletal muscle innervation. J. Neurosci. 24:8181–8191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater, C.R. 1982. Postnatal maturation of nerve-muscle junctions in hindlimb muscles of the mouse. Dev. Biol. 94:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, S.P., E.L. McDearmon, S. Li, J.M. Ervasti, K. Tryggvason, and P.D. Yurchenco. 2002. Contributions of the LG modules and furin processing to laminin-2 functions. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18928–18937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son, Y.J., B.L. Patton, and J.R. Sanes. 1999. Induction of presynaptic differentiation in cultured neurons by extracellular matrix components. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11:3457–3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, J.E., D.J. Glass, G.D. Yancopoulos, and Z.W. Hall. 1997. Laminin-induced acetylcholine receptor clustering: an alternative pathway. J. Cell Biol. 139:181–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, N., F. Yokoyama, and M. Nomizu. 2005. Functional sites in the laminin alpha chains. Connect. Tissue Res. 46:142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talts, J.F., T. Sasaki, N. Miosge, W. Gohring, K. Mann, R. Mayne, and R. Timpl. 2000. Structural and functional analysis of the recombinant G domain of the laminin alpha4 chain and its proteolytic processing in tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 275:35192–35199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl, R., D. Tisi, J.F. Talts, Z. Andac, T. Sasaki, and E. Hohenester. 2000. Structure and function of laminin LG modules. Matrix Biol. 19:309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, Z., C.N. Christian, M. Vigny, H.C. Bauer, P. Sonderegger, and M.P. Daniels. 1983. Laminin induces acetylcholine receptor aggregation on cultured myotubes and enhances the receptor aggregation activity of a neuronal factor. J. Neurosci. 3:1058–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X., S. Arber, C. William, L. Li, Y. Tanabe, T.M. Jessell, C. Birchmeier, and S.J. Burden. 2001. Patterning of muscle acetylcholine receptor gene expression in the absence of motor innervation. Neuron. 30:399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, R.A., M.D. Henry, K.J. Daniels, R.F. Hrstka, J.C. Lee, Y. Sunada, O. Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya, and K.P. Campbell. 1997. Dystroglycan is essential for early embryonic development: disruption of Reichert's membrane in Dag1-null mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6:831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.