Abstract

Rationale:

Opioids have become part of contemporary treatment in the management of chronic pain. However, chronic use of opioids has been associated with high prevalence of sleep apnea which could contribute to morbidity and mortality of such patients.

Objectives:

The main aim of this study was to treat sleep apnea in patients on chronic opioids.

Methods:

Five consecutive patients who were referred for evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea underwent polysomnography followed by a second night therapy with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device. Because CPAP proved ineffective, patients underwent a third night therapy with adaptive pressure support servoventilation.

Main Results:

The average age of the patients was 51 years. They were habitual snorers with excessive daytime sleepiness. Four suffered from chronic low back pain and one had trigeminal neuralgia. They were on opioids for 2 to 5 years before sleep apnea was diagnosed. The average apnea-hypopnea index was 70/hr. With CPAP therapy, the apnea-hypopnea index decreased to 55/hr, while the central apnea index increased from 26 to 37/hr. The patients then underwent titration with adaptive pressure support servoventilation. At final pressure, the hypopnea index was 13/hr, with central and obstructive apnea index of 0 per hour.

Conclusions:

Opioids may cause severe sleep apnea syndrome. Acute treatment with CPAP eliminates obstructive apneas but increases central apneas. Adaptive pressure support servoventilation proves to be effective in the treatment of sleep related breathing disorders in patients on chronic opioids. Long-term studies on a large number of patients are necessary to determine if treatment of sleep apnea improves quality of life, decreases daytime sleepiness, and ultimately decreases the likelihood of unexpected death of patients on opioids.

Citation:

Javaheri S; Malik A; Smith J; Chung E. Adaptive pressure support servoventilation: a novel treatment for sleep apnea associated with use of opioids. J Clin Sleep Med 2008;4(4):305-310.

Keywords: Morphine, oxycontin, APSSV, CPAP, OSA, CSA

In the last decade, there has been a major change in the management of chronic pain with a marked increase in the therapeutic use of opioids.1–3 The notion has been promoted that with chronic administration of opioids, respiratory tolerance develops and respiratory depression is frequently absent or mild in nature.1,2 This notion is to some extent correct, in that during wakefulness, chronic respiratory acidosis is commonly not observed or is mild in nature,4,5 During sleep, however, respiratory depression is seen, as reflected by obstructive and central apneas and hypopneas. Recent systematic studies6–9 have demonstrated that 30% to 90% of patients on opioids have sleep apnea, the severity of which is dose dependent.9 Consequently, with widespread use of opioids for pain management, a large number of patients could suffer from sleep apnea. Because both obstructive and central sleep apnea may contribute to the mortality of patients with these sleep related breathing disorders,10,11 sleep apnea may also be a risk factor for mortality of patients on opioids.12,13 This speculation is supported by the excess mortality of young individuals on opioids who may be found dead in bed, with the cause in several of them remaining unknown.14 It is, therefore, conceivable that the therapy of sleep apnea in patients on opioids could prevent sleep related mortality, as it does in the general population.11,15 The present study is the first attempt to treat sleep apnea in patients on opioids.

METHODS

Design

During an 18-month period, from April 2006 to Sept 2007, one of the authors (SJ) saw 5 consecutive patients using opioids chronically for pain management. They were referred for evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Patients were seen in consultation and underwent full-night polysomnography. During the follow-up visit, results of sleep studies were reviewed, mechanisms of upper airway obstruction explained, a CPAP device was shown to the patients, and therapeutic effects of CPAP and the process of CPAP titration were explained. Patients were also informed about presence of central apnea and its association with use of opioids. Because use of CPAP resulted in an increase in central apnea, therapy with adaptive pressure support servoventilation (APSSV) was recommended. The operation of this device was also explained.

The patients were part of a large retrospective study on CPAP-emergent central sleep apnea, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Christ Hospital in Cincinnati.

Procedures

Polysomnography was performed using standard techniques as detailed previously.16,17 For staging sleep, we recorded electroencephalogram (2 channels), chin electromyogram (1 channel) and electrooculogram (2 channels). Thoracoabdominal excursions were measured qualitatively by piezo crystal technology (Model 1314 Sleepmate Technologies, Midlothian, VA), with sensors placed over the rib cage and abdomen. Airflow was qualitatively monitored using an oral/nasal pressure transducer (PTAF 2, Mukilteo, WA) in 4 patients and a thermistor (Model 1459 Sleepmate Technologies, Midlothian, VA) in one patient. Arterial blood oxyhemoglobin saturation was recorded using a finger pulse dosimeter (Healthdyne Oximeter Model 930, Respironics Inc. Murrysville, PA). These variables were recorded on a multichannel computerized polysomnographic system (Model Alice III with PPI-2, Respironics Inc. Murrysville, PA). An apnea was defined as cessation of inspiratory airflow (flat signal) for ≥10 seconds. An obstructive apnea was defined as the absence of airflow in the presence of rib cage and abdominal excursions. A central apnea was defined as the absence of airflow with absence of rib cage and abdominal excursions (flat signals from these probes). Hypopnea was defined as a reduction of airflow (30%) and/or thoracoabdominal excursions lasting ≥ 10 sec associated with ≥ 4% drop in SpO2 and/or an arousal, as defined elsewhere.18 The number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep is referred to as the apnea-hypopnea index. The number of arousals per hour of sleep is referred to as the arousal index. All polysomnograms were reviewed by one of the authors (SJ).

CPAP (Respironics Inc., Murrysville, PA) titration was performed using a uniform approach. Titration began usually at pressure of 5 cm H2O, and every few minutes the pressure was increased to eliminate obstructive apneas, hypopneas, and eventually snoring. If during titration, central apneas emerged, the pressure was not increased beyond 3 to 4 cm H2O. For one patient who was intolerant of CPAP (complaining of difficulty exhaling), a bilevel device was used (BiPAP Synchrony, Respironics Inc., Murrysville, PA). The expiratory pressure was set at the level which had eliminated obstructive apneas, and the inspiratory pressure was increased gradually to eliminate hypopneas.

Titration with adaptive pressure support servoventilation (VPAP Adapt SV, ResMed Corp, Poway, CA) began with an expiratory pressure set at the level which had eliminated obstructive apneas during CPAP titration; the minimum pressure support was set at 3 cm H2O, with a maximum pressure support at 10 cm H2O and a backup rate of 15 breaths per minute. The pressure support was increased gradually to eliminate hypopneas, snoring, and flow limitation.

Statistical Analysis

For multiple comparisons, analysis of variance with repeated measures and Bonferroni correction factor was used. For data that were not normally distributed, Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance and Dunn tests were used. When only 2 variables were compared, either 2-tailed paired t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. p < 0.05 (after multiple comparisons) was considered significant. Means ± SD are reported. Calculations were done using Graph Pad InStat 3.

RESULTS

Our patients were middle-aged subjects who presented with symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea, including habitual snoring, unrestorative sleep, witnessed apnea, gasping, nocturia, and excessive daytime sleepiness (Table 1). Two were receiving medications for hypertension and 2 for reflux disease. Three patients had history of depression, 2 were on fluoxetine, 1 on sertraline, 2 on clonazepam, and 1 on zolpidem. Two patients had been previously (2 years ago) diagnosed with OSA, and were non-adherent to CPAP therapy. One of the patients had polysomnography in our laboratory with AHI = 37/hr and CAI = 1.2/hr. Later, he was treated with opioids for pain and his repeated polysomnography showed an AHI = 66/hr and CAI = 44/hr.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Patients

| Variables | Mean ±SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 51 ± 4 | 44–54 |

| Height, cm | 182 ± 8 | 168–190 |

| Weight, kg | 96 ± 11 | 82–109 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31 ± 4 | 25–35 |

| Neck circumference, cm | 40 ± 2 | 38–42 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | 14 ± 4 | 10–20 |

| Opioid dose (morphine equivalent), mg | 252 ± 150 | 120–450 |

There were 4 males patients receiving opioids: 3 for chronic low back pain and one for trigeminal neuralgia. The female patient suffered from chronic low back pain (for which she was receiving opioids), depression, and Chiari malformation. At the time of consultation, the patients had been on opioids for 2 to 5 years.. The opioids administered included fentanyl patch and oxycodone and morphine by mouth; equivalent-morphine doses are depicted in Table 1.

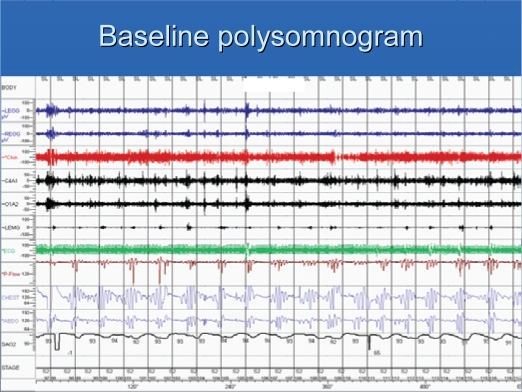

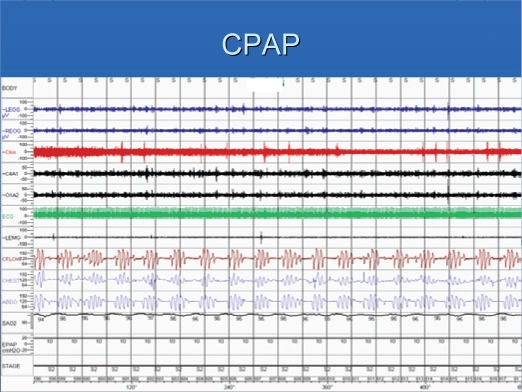

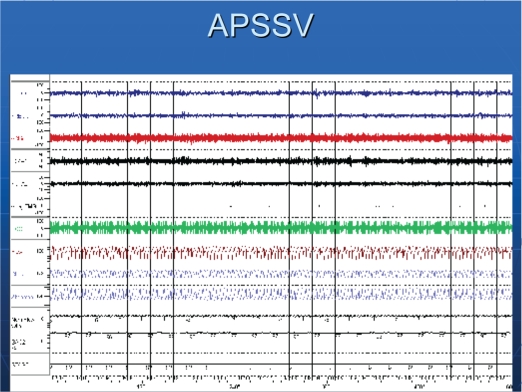

Patients had severe sleep apnea, with an average AHI of 70/hr (Table 2). The central apnea index was 26/hr, with an obstructive apnea index of about 6/hr. Figure 1 shows a recording of 10-min period of a patient in stage 2 sleep. Episodes of obstructive and central apneas are present. Central apneas occurred primarily in NREM sleep. While on CPAP, obstructive apneas were eliminated, but central apneas increased (Figure 2). Similar to baseline polysomnographic findings, while on CPAP, central apneas also occurred mostly in NREM sleep. With APSSV, all central apneas were eliminated (Figure 3) and the apnea-hypopnea index decreased significantly, to about 20/hr (Table 2). In association with reduction in sleep apneas and hypopneas, total arousal index and arousal index due to respiratory disturbances decreased (Table 3) with APSSV. Further, stage 1 sleep decreased significantly, as stage 2 increased.

Table 2.

Sleep Disordered Breathing Events at Baseline and While on CPAP and APSSV

| Variables | Baseline | CPAP | APSSV | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apnea hypopnea index, n/hr | 70 ± 19 | 55 ± 25 | 20 ± 8†* | 0.006 |

| NREM AHI, n/hr | 78 ± 24 | 60 ± 28 | 20 ± 8†* | 0.03 |

| REM AHI, n/hr | 22 ± 24 | 9 ± 7 | 13 ± 13 | 0.6 |

| Central apnea index, n/hr | 26 ± 27 | 37 ± 21 | 0 ± 0* | 0.01 |

| NREM CAI, n/hr | 31 ± 34 | 41 ± 24 | 0 ± 0 | 0.08 |

| REM CAI, n/hr | 7 ± 10 | 5 ± 7 | 0 ± 0 | na |

| Obstructive apnea index, n/hr | 6 ± 7 | 1 ± 2 | 0 ± 0 | 0.01 |

| NREM OAI, n/hr | 7 ± 8 | 2 ± 2 | 0 ± 0 | 0.08 |

| REM OAI, n/hr | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | na |

| Hyponea index, n/hr | 36 ± 15 | 16 ± 7 | 20 ± 8 | 0.04 |

| NREM HI, n/hr | 39 ± 22 | 17 ± 7 | 20 ± 8 | 0.4 |

| REM HI, n/hr | 27 ± 24 | 4 ± 2 | 13 ± 13 | 0.2 |

| ArI, n/hr | 62 ± 18 | 35 ± 20 | 24 ± 9† | 0.02 |

| Respiratory disturbance ArI, n/hr | 58 ± 17 | 30 ± 19 | 16 ± 7† | 0.01 |

| Baseline SpO2, % | 95 ± 2 | 96 ± 23 | 95 ± 3 | 0.2 |

| Minimum SpO2, % | 86 ± 4 | 88 ± 2 | 88 ± 3 | 0.7 |

Mean ±SD; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; APSSV = adaptive pressure support servoventilation; Disordered breathing events are across the night. ArI = Arousal index; †Significant vs. Baseline; *Significant CPAP vs. APSSV.

Figure 1.

A 10-min epoch of polysomnogram showing obstructive and central apneas, and hypopneas. Note fluctuations in SpO2, which parallel apneas and hypopneas. Arousals coincide with resumption of breathing after an apnea and are characterized by changes (elevations) in EEG and eye and leg movements.

Figure 2.

The same patient on CPAP at pressure of 10 cm H2O. There are many central apneas associated with arousals.

Figure 3.

The same patient on adaptive pressure support servoventilation. Note uninterrupted breathing without any central or obstructive disordered breathing events.

Table 3.

Disordered breathing events at baseline and while on CPAP and APSSV

| Variables | Baseline | CPAP | APSSV | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dark time, hr | 6.8 ± 1 | 6.6 ± 1 | 6.6 ± 1 | 0.9 |

| Total sleep time, hr | 5.6 ± 1 | 4.7 ± 1 | 5.0 ± 1 | 0.2 |

| Sleep efficiency, % | 82 ± 8 | 72 ± 11 | 76 ± 8 | 0.08 |

| Stage 1, % TST | 7 ± 1 | 16 ± 3† | 8 ± 3* | 0.006 |

| Stage 2, % TST | 78 ± 9 | 77 ± 7 | 80 ± 8 | 0.2 |

| Stages 3 & 4, % TST | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0 | 1 ± 2 | 0.6 |

| REM sleep, % TST | 15 ± 9 | 11 ± 5 | 11 ± 8 | 0.4 |

| Arousal index, n/hr | 62 ± 18 | 35 ± 20 | 24 ± 9† | 0.02 |

| Respiratory disturbance ArI, n/hr | 58 ± 17 | 30 ±19 | 16 ±7† | 0.01 |

| PLMSI, n/hr | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.5±1 | 0.7 |

Mean ± SD; Total dark time = period from lights out to lights on. PLMSI = Periodic leg movements index during sleep; TST = total sleep time; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; APSSV = adaptive pressure support servoventilation; †Significant vs. Baseline; *Significant CPAP vs. APSSV.

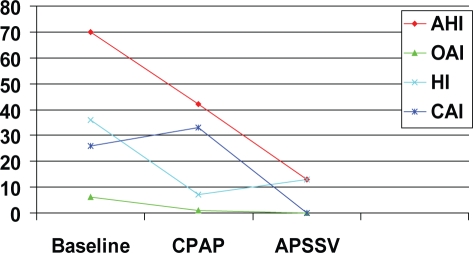

Figure 4 shows the mean values for apneas and hypopneas at baseline, while on final pressure for CPAP, and APSSV devices. The respective values for AHI were 70, 42, and 13 per hour (p = 0.04, CPAP vs APSSV). Whereas, obstructive apnea index was ≤ 1/hr while on both positive airway pressure devices, the central apnea index was about 33 while on CPAP and 0 per hour on APSSV (p = 0.01). The mean value for final CPAP level was 8.5 ± 2 cm H2O which was not significantly different for the final mean value of expiratory pressure of APSSV (7 ± 2 cm H2O). The minimum and maximum inspiratory support pressures were 5 cm H2O and 10 cm H2O, respectively.

Figure 4.

Mean values for various sleep disordered breathing events at final continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and adaptive pressure support servoventilation (APSSV). Note the reduction in apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and elimination of central apneas with APSSV.

DISCUSSION

We report acute effects of 2 positive airway pressure devices. The patients underwent 3 nights of polysomnographic studies. The patients had severe sleep apnea-hyponea with an average index of 70/hr. The average AHI decreased to 42/hr while on CPAP and to 13/hr on final APSSV (Figure 4).The reduction in AHI with APSSV is remarkable for first-night acute titration. Therapy with CPAP resulted in virtual elimination of obstructive apneas as expected, whereas central apneas increased; in contrast, with the use of APSSV, both obstructive and central apneas were eliminated and sleep architecture improved.

The operation of a CPAP device is well known. It provides constant positive airway pressure throughout the breathing cycle. CPAP devices have been successfully used to treat obstructive sleep apnea and also, to a lesser degree, to treat central sleep apnea in systolic heart failure.15,19 The operation of APSSV is different from that of CPAP.20–26 The expiratory pressure is set at the level of CPAP to eliminate obstructive apneas. The device provides a variable amount of inspiratory support (above the expiratory pressure) to eliminate hypopneas. In addition, as noted, a backup rate can be set, which aborts any impending central apneas. With these settings, the device is able to effectively control both obstructive and central apnea; hypopneas are also decreased. (Table 2 and Figure 4).

APSSV has been used to treat sleep apnea in systolic heart failure and CPAP-emergent central apnea, and the results have been promising,20–24,26 although no long-term systematic studies are available. Interestingly, the pattern of breathing in patients on chronic opioids is similar to that seen in patients with systolic heart failure; in both conditions, central and obstructive disordered breathing may occur during sleep in the same patient. In both conditions, therapy with CPAP eliminates obstructive apneas, as expected, but central apneas may persist.19 In both conditions, central apneas occur mostly in NREM sleep, both at baseline and while on CPAP, reflecting differences in neurophysiology and control of breathing in NREM and REM sleep.27 A major difference, however, exists in the pattern of breathing of patients with systolic heart failure compared to patients on opioids. In the former, the breathing cycle is characterized by gradual decrescendo arm commonly ending in a central apnea, followed by a long crescendo arm out of apnea.28,29 This pattern of breathing is referred to Hunter-Cheyne-Stokes breathing (Hunter being the physician who first described this pattern of breathing 37 years before John Cheyne as reviewed28,29 elsewhere). The prolonged length of the breathing cycle relates to the long arterial circulation time, a pathological feature of systolic heart failure. In contrast, episodes of disordered breathing events associated with the use of opioids are similar to those seen in ataxic breathing, and breaths at the end of apneas are abrupt (Figure 1) rather than smooth and gradual. Despite these differences, APSSV effectively treats sleep disordered breathing in systolic heart failure20–24 and that associated with the use of opioids. (Figure 4).

During the last decade, there has been a dramatic change in the management of chronic pain, associated with a marked increase in the use of opioids.1–3 These drugs, which were sparingly used in the past, are currently in common use for management of chronic pain associated with neuromuscular disorders (as seen in the patients in this study). The increase in the use of opioids is related to a number of issues; the most important cause is the position of the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine in 1997.1,2 Their joint statement implied that it is acceptable to use opioids for treatment of chronic pain, with minimal risk of respiratory depression. This is only partly correct; although acute use of opioids may cause CO2 retention, chronic respiratory acidosis, a reflection of long-term diurnal respiratory depression, is not common in patients on chronic opioids and if present, is mild,4,5 (although the magnitude of CO2 retention may be dose dependent). However, respiratory depression in the form of sleep apneas and hypopneas, both obstructive and central, is prevalent in patients who chronically use opioids. Wang and associates7 showed presence of sleep apnea in 30% of a group of patients in a methadone maintenance treatment program. In another report, Walker et al.9 performed polysomnography in a cohort of 60 patients taking opioids for pain management. The patients were matched for age, gender, and body mass with 60 patients not taking opioids. Authors reported that patients on opioids had a significantly higher apnea-hypopnea index than the control group, primarily due to an increase in the number of central apneas. As in the present study, the authors also reported that central apneas were primarily in NREM sleep. Walker and associates9 observed a dose-response relationship between morphine dose equivalent and the apnea-hypopnea index. Ninety-two percent of the patients who were on a morphine dose equivalent to ≥ 200 mg had sleep apnea. In the present study, 3 of 5 patients were taking more than 200 mg of morphine per day.

As noted above, use of opioids as a risk factor for sleep apnea is now well established.6–9 The present study reports treatment of opioid-associated disordered breathing events with 2 positive airway pressure devices. We found that CPAP was effective in eliminating obstructive apneas as expected, but central apneas increased, resulting in disturbed sleep architecture. With adaptive pressure support servoventilation, sleep apnea improved significantly.

Clinical Implications

There has been a dramatic increase in the therapeutic use of opioids in the management of chronic pain in the last decade. Studies indicate that the use of some opioids such as methadone and oxycodone has increased many-fold in a short period.3 With recent findings indicating a high prevalence of sleep apnea in patients using opioids,6–9 particularly above a 200-mg dose equivalent of morphine, a large number of patients on chronic opioids may suffer from sleep apnea. Also of importance, Caravati et al.12 reported an increase in the mortality rate associated with the rising prescription rate of opioids. Teichtahl et al.6 proposed that sleep disordered breathing may play a role in unexplained excess mortality in patients treated with methadone. Interestingly, Porucznik and associates14 reported that these decedents were discovered dead in the morning or dead in bed during the day. It is, therefore, conceivable that sleep apnea may contribute to the mortality of patients who use opioids, as it does in patients with heart disease10 and those with obstructive sleep apnea independent of preexisting cardiac disease.11 In the absence of any guidelines and long-term studies, diagnosis and appropriate therapy of sleep apnea in patients using opioids, particularly those using more than the equivalent of 200 mg of morphine, is warranted. In this study, we found that effective treatment is achieved by the use of adaptive pressure support servoventilation.

Summary

The results of this small study show that patients on opioids may suffer from severe sleep apnea, and that acute CPAP therapy, which effectively eliminates obstructive apnea, is ineffective in eliminating central apneas. In contrast, APSSV is quite effective in eliminating both obstructive and central apneas. It is conceivable that effective treatment of sleep apnea in patients on opioids could decrease the likelihood of the unexpected deaths of these patients.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Javaheri has received research support from Respironics and has consulted for and participated in speaking engagements for Respironics and ResMed. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Pain Medicine and American Pain Society. The use of opioids for chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon D, Dahl J, Miaskowski C, et al. American pain society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1574–80. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pletcher M, Kertesz S, Kohn M, et al. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity or patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299:70–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teichtahl H, Wang D, Cunnington D, et al. Cardiorespiratory function in stable methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) patients. Addict Biol. 2004;9:247–53. doi: 10.1080/13556210412331292578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santiago T, Pugliese A, Edelman N. Control of breathing during methadone addiction. Am J Med. 1977;62:347–54. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90831-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teichtahl H, Promdromidis A, Miller B, Cherry G, Kronborg I. Sleep-disordered breathing in stable methadone programme patients: a pilot program. Addiction. 2001;96:395–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9633954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Teichtahl H, Drummer O, et al. Central sleep apnea in stable methadone maintenance treatment patients. Chest. 2005;228:1348–56. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farney RJ, Walker JM, Cloward T, Rhondeau S. Sleep-disordered breathing associated with long-term opioid therapy. Chest. 2003;123:632–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker M, Farney J, et al. Chronic opioid use a risk factor for the development of central sleep apnea and ataxic breathing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:455–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javaheri S, Shukla R, Zeigler H, et al. Central sleep apnea, right ventricular dysfunction, and low diastolic blood pressure are predictors of mortality in systolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2028–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marin JM, Carriso SJ, Vincente E, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365:1046–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caravati EM, Grey T, Nangle B, Rolfs RT, Peterson-Porucznik CA. CDC: Increase in poisoning deaths caused by non-illicit drugs-Utah 1991-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg J. Mortality and return to work of drug abusers from therapeutic community treatment 3 years after entry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;5:164–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v05n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porucznik CA, Farney RJ, Walker JM, Rolfs RT, Grey T. Increased mortality rate associated with prescribed opioid medications: is there a link with sleep disordered breathing?. Eur Respir J; Presented at 15th Annual Congress, European Respiratory Society; 20 Sep 2005; Copenhagen, Denmark. 2005. p. 596. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arzt M, Floras J, Logan A, et al. Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in hear failure. Circulation. 2007:3173–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Javaheri S, Colangelo G, Lacey W, Gartside PS. Chronic hypercapnia in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1994;17:416–23. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.5.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javaheri S. A mechanism of central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:949–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnet M, Carley D, Carskadon M, et al. ASDA Report; EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples. Sleep. 1992;15:174–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javaheri S. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on sleep apnea and ventricular irritability in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101:392–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teschler H, Dohring J, Wang Y, et al. Adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation a novel treatment for Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;164:614–19. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.9908114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pepperell J, Maskell N, Jones D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of adaptive ventilation for Cheyne-Stokes breathing in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1109–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200212-1476OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szollosi I, O'Driscoll DM, Dayer MJ, et al. Adaptive servo-ventilation and dead space: effects on central sleep apnoea. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasai T, Narui K, Dohi T, et al. First experience of using new adaptive servo-ventilation device for Cheyne-Stokes respiration with central sleep apnea among Japanese patients with congestive heart failure. Report of 4 clinical cases. Circ J. 2006;70:1148–54. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philippe C, Stoica-Herman M, Drouot, et al. Compliance with and effectiveness of adaptive servoventilation versus continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of Cheyne-Stokes, respiration in heart failure over a six month period. Heart. 2006;92:337–42. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.060038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banno K, Okamura K, Kryger M. Adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with idiopathic Cheyne-Stokes breathing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgenthaler T, Kagramanov V, Hanak V, et al. Complex sleep apnea syndrome: is it a unique clinical syndrome? Sleep. 2006;29:1203–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Javaheri S, Dempsey J. Mechanisms of sleep apnea and periodic breathing in systolic heart failure. Sleep Med Clin. 2007;2:623–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javaheri S. Heart failure. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005. pp. 1208–17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Javaheri S. Central sleep apnea. In: Lee-Chiong TL, editor. Sleep: a comprehensive handbook. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Liss; 2006. pp. 249–62. [Google Scholar]