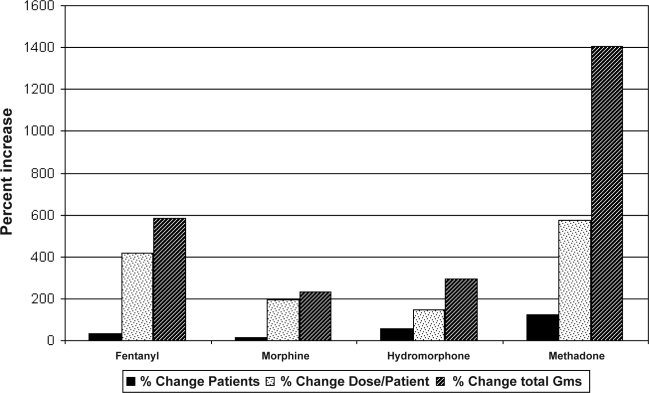

Medical use of chronic opioids has increased dramatically in the last two decades. Even prior to the 1997 consensus statement on the use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain issued by the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society that advocated liberalization of opioids for chronic pain, prescribed fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine, and oxycodone had increased by 1168%, 19%, 59%, and 23% respectively (grams of drug per 100,000 population).1,2 Since the 1997 statement, the total doses of these same drugs has further escalated by an additional 235% to 1403% (Figure).3 Clearly, more and more of our patients are using narcotics, and at higher average doses than previously. It is therefore very timely to understand how chronic opioids affect the sleeping patient, and what may be done about the special sleep disordered breathing patterns that develop. Many have somewhat naively accepted the assumption that ventilation is only little effected by chronic opioid use; available data to support this are sparse and were not drawn from sleeping patients.2,4 Indeed, many subsequent reports demonstrate an increased frequency of sleep disordered breathing among patients chronically using opioids.4–8

Two studies published in this issue and prior publications illustrate several points: (1) Chronic opioid use is associated with complex sleep apnea, (2) Chronic opioid users tend to have disproportionally low arousal indexes and high sleep efficiency relative to the degree of measured sleep disordered breathing, (3) CPAP alone is often ineffective in controlling sleep disordered breathing due to the persistence and or emergence of centrally mediated periodic or ataxic central sleep apnea patterns (at least acutely), and (4) at least in one study, adaptive servoventilation (ASV) was more effective acutely than CPAP.

Farney et al. describe a case series of 22 chronic opioid using patients referred for suspected sleep disordered breathing in whom they attempted use of an adaptive servoventilator (ASV) to control complex sleep disordered breathing.9 In their study, non-standard methods were used for measuring “flow” during positive airway titration (use of pressure transducer attached to the tubing close to the mask).10,11 They indicate that for most of their patients, the VPAP Adapt SV (ResMed Inc., Poway, CA) device was used with end-expiratory pressure (EEP) set at 5 cm H2O and not titrated, while the back-up ventilatory rate was set at 15 breaths per minute. With these settings, since EEP might be below the pressure needed to maintain airway patency, patient efforts to breath would not be sensed if present, while programmed positive pressure efforts delivered by ASV would be interpreted as breaths regardless of whether there was flow or not (consider a delivered breath against a partially or completely closed glottis, present due to inadequate EEP). Additionally, the VPAP AdaptSV, when left in the automatic settings, typically uses “fuzzy logic” to determine not only the pressure support for inspiratory breaths, but the back-up ventilatory rate as well, incorporating goals to normalize minute ventilation toward 90% of locally measured mean, rather than at a fixed ventilatory rate of 15. Conclusions regarding effectiveness of ASV under these circumstances must necessarily be only tentative, and the most reliable data is from their diagnostic studies. Similar to their prior descriptions, they found significant sleep disordered breathing, with an average apnea hypopnea index (AHI) of 66.6, and a high prevalence of central apneas and ataxic breathing.4 The degree of ventilatory ataxia was judged moderate to severe in 19/20 patients using a non-validated semiquantitative pattern recognition grading system. Application of CPAP did not did not appear to materially improve the overall AHI; centrally mediated sleep disordered breathing persisted or increased during application of CPAP.

In Javaheri et al., five chronic opioid using patients evaluated for suspected sleep disordered breathing were of similar age, body mass index, and also suffered from subjective excessive daytime sleepiness.12 Similar to the findings of Farney et al, CPAP was effective in reducing the obstructive apneas, but central apneas, and hypopneas (which we assume were predominantly central in nature) continued at a high rate, leaving a high residual AHI (55/hr). Notably, two of their five patients had previously been prescribed CPAP and were intolerant. Though not directly indicated, one speculates whether they did not use CPAP because it was ineffective. In contrast to the Farney study, Javaheri et al. adjusted the EEP on their ASV to eliminate obstructive events, and found it to be very effective, with reduction of the mean AHI from the baseline of 70 to 13.

From these and other studies, it is clear that sleep disordered breathing in chronic opioid users represents a form of complex sleep apnea, with elements of both upper airway obstruction and central sleep apnea present simultaneously.5,7,12 This complexity may be suggested (at least in some of the cases for which polysomnographic tracings were shown) prior to application of CPAP by virtue of the extremely periodic nature of the apneas and hypopneas noted during the diagnostic test (see Farney et al, Figure 4a, and Javaheri et al, Figure 1).9,12 In both of these tracings, periodic breathing appears present in NREM sleep that is characterized by a shorter period than seen in classic Cheyne-Stokes ventilation (about 30 sec vs. > 45 sec). Similar to prior descriptions of CompSAS, the overall AHI (and especially the central apnea index, see Javaheri et al) is reduced in REM compared with NREM sleep, a contrast to usual obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.13,14 The opioid-induced CompSAS often also includes highly irregular central patterns, as pointed out by Farney et al.9 The combination of significant obstructive and central sleep apnea together describe CompSAS.15 The appearance of these features prior to application of CPAP strongly suggests pre-existing abnormalities of chemosensitivity as an underlying etiology for CompSAS, rather than an unusual response to CPAP.

Figure 1.

Change in Narcotic Prescriptions 1997–2006

In contrast to non-opioid related CompSAS, patients in these two series show relatively mild degrees of sleep architectural abnormalities relative to their high breathing event frequency. In Farney et al, the baseline AHI was 66.6, the arousal index only 16, and the proportion of Stage N1 was 8.4%, while in the Javaheri series, the AHI was 70, arousal index 62, and proportion of Stage N1 was 7%.9,12 Prior work also suggests lower proportions of Stage N1 and arousal indexes in chronic opioid users than in non-opioid users with sleep disordered breathing.5,7 This combination of an apparently higher arousal threshold for ventilatory events, a high prevalence of sleep disordered breathing, and the combination of obstructive and centrally medicated sleep apnea may be a dangerous combination, perhaps explaining the increase in sleep or bed-related mortality noted among chronic opioid users.16,17

In these two case series, ASV was effective in treating CompSAS in one study, but not the other. The latter result may reflect suboptimal titration of the device (they indicate that few of their patients in the series had EEP adjusted beyond 5 cm H2O) coupled with the non-standard measurement technique employed by Farney et al. However, it may also be that their patients did have a more ataxic breathing pattern, and that ASV will be less successful in these patients. Certainly more studies will be needed to determine this.

Despite the limitations of these data, they raise an important and subtle point regarding ASV in the treatment of central and complex sleep apnea: what should be the measure of ventilatory stability? I might suggest that normalization of the AHI is one indicator, but may not be the best. Ventilatory stability may be better demonstrated by elimination of the variability of the inspiratory pressure compensation required by the ASV to normalize the AHI, rather than only normalization of the AHI itself. The machine's capabilities are substantial and responsive, such that the flow pattern may be improved and almost normalized despite underlying cyclic variation in ventilatory output (therefore, not a true stable pattern). Presumably, the true stabilization of central sleep apnea and CompSAS occurs when both hypoventilation and hyperventilatory overshoot is eliminated and the carbon dioxide tensions are normalized. Whether this goal may be accomplished in chronic opiate use related CompSAS or not remains to be demonstrated, but for the present, those who do not respond to CPAP deserve a trial of appropriately titrated ASV.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author has indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joranson DE, Ryan KM, Gilson AM, Dahl JL. Trends in medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics. JAMA. 2000;283:1710–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson PR, Caplan RA, Connis RT, et al. Practice guidelines for chronic pain management. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:995–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.2008 www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov. ARCOS Retail Drug Summary Reports.

- 4.Farney RJ, Walker JM, Cloward TV, Rhondeau S. Sleep-disordered breathing associated with long-term opioid therapy. Chest. 2003;123:632–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Teichtahl H, Drummer O, et al. Central sleep apnea in stable methadone maintenance treatment patients. Chest. 2005;128:1348–56. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker JM, Farney RJ, Rhondeau SM, et al. Chronic opioid use is a risk factor for the development of central sleep apnea and ataxic breathing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:455–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teichtahl H, Prodromidis A, Miller B, Cherry G, Kronborg I. Sleep-disordered breathing in stable methadone programme patients: A pilot study. Addiction. 2001;96:395–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9633954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhawan R, Lieno C, Chesson A, Desai S. Opioid-induced sleep breathing abnormalities. Diagnostic and therapeutic features, dose dependent phenomenon. Sleep. 2004;27:206–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farney RJ, Walker JM, Boyle KM, Cloward TV, Shilling KC. Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) in patients with sleep disordered breathing associated with chronic opioid medications for non-malignant pain. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:311–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kushida CA, Chediak A, Berry RB, et al. Clinical guidelines for the manual titration of positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:157–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AJ, Quan S. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specification. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Javaheri S, Malik A, Smith J, Chung E. Adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation: a novel treatment for sleep apnea associated with use of opioids. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:305–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allam JS, Olson EJ, Gay PC, Morgenthaler TI. Efficacy of adaptive servoventilation in treatment of complex and central sleep apnea syndromes. Chest. 2007;132:1839–46. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgenthaler TI, Kagramanov V, Hanak V, Decker PA. Complex sleep apnea syndrome: is it a unique clinical syndrome? Sleep. 2006;29:1203–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilmartin GS, Daly RW, Thomas RJ. Recognition and management of complex sleep-disordered breathing. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:485–93. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000183061.98665.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increase in poisoning deaths caused by non-illicit drugs--Utah 1991–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porucznik CA, Farney RJ, Walker JM, Rolfs RT, Grey T. Increased mortality rate associated with prescribed opioid medications: Is there a link with sleep disordered breathing?. Eur Respir J; Presented at 15th Annual Congress, European Respiratory Society; 20 Sep 2005; Copenhagen, Denmark. 2005. p. 596. [Google Scholar]