Abstract

In the absence of immune surveillance, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected B cells generate neoplasms in vivo and transformed cell lines in vitro. In an in vitro system which modeled the first steps of in vivo immune control over posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease and lymphomas, our investigators previously demonstrated that memory CD4+ T cells reactive to EBV were necessary and sufficient to prevent proliferation of B cells newly infected by EBV (S. Nikiforow et al., J. Virol. 75:3740-3752, 2001). Here, we show that three CD4+-T-cell clones reactive to the latent EBV antigen EBNA1 also prevent the proliferation of newly infected B cells from major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-matched donors, a crucial first step in the transformation process. EBNA1-reactive T-cell clones recognized B cells as early as 4 days after EBV infection through an HLA-DR-restricted interaction. They secreted Th1-type and Th2-type cytokines and lysed EBV-transformed established lymphoblastoid cell lines via a Fas/Fas ligand-dependent mechanism. Once specifically activated, they also caused bystander regression and bystander killing of non-MHC-matched EBV-infected B cells. Since EBNA1 is recognized by CD4+ T cells from nearly all EBV-seropositive individuals and evades detection by CD8+ T cells, EBNA1-reactive CD4+ T cells may control de novo expansion of B cells following EBV infection in vivo. Thus, EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones may find use as adoptive immunotherapy against EBV-related lymphoproliferative disease and many other EBV-associated tumors.

B-cell lymphomas related to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) occur in patients with immune deficiencies. Immune dysregulation, which predisposes patients to B-cell lymphomas and EBV-induced B-cell lymphoproliferative disease (LPD), may result from genetic abnormalities affecting lymphocytes (e.g., severe combined immunodeficiency, X-linked lymphoproliferative disease), viral infection of T cells (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS), or immunosuppressive medical treatments directed against T cells, such as FK506, cyclosporine A, corticosteroids, depletion of T cells, or OKT3 T-cell-toxic antibodies (14, 21, 32, 62, 76). Whether lack of NK, of CD4+, or of CD8+ T-cell function allows for the outgrowth of EBV-infected B-cell lymphomas in these individuals remains unclear. Adoptive immunotherapy with polyclonal T-cell lines consisting of mixtures of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in various proportions can prevent EBV-induced lymphomas and LPDs that occur in the settings of bone marrow and solid organ transplantation (23, 26, 47, 75, 80, 81, 96).

Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells that recognize latent EBV products, and perhaps lytic antigens, are likely to play a significant role in curtailing proliferation of EBV-transformed cells in vivo (28, 40, 49, 68). In comparison to the large numbers of EBV-reactive CD8+-T-cell clones which have been generated, only a few CD4+-T-cell clones which recognize EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1), EBNA2, BHRF1, and gp340 have been isolated (8, 25, 37, 50, 67, 78, 91, 92). However, recent findings emphasize the importance of CD4+-T-cell effector function against EBV antigens (22, 60, 85, 94). Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) lines consisting primarily of CD4+ T cells have been effective in immunotherapy against LPDs (59, 84). Activated CD4+ T cells derived from fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) can prevent outgrowth of newly infected B cells (57, 86). EBV-reactive CD4+-T-cell lines have been shown to lyse lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) via various mechanisms. However, the antigen specificity of all but one of the T-cell lines used in these experiments remains unknown (27, 93).

A significant proportion of memory CD4+ T cells that recognize autologous LCLs are directed against the EBNA1 protein (43, 55). EBNA1 is expressed in every form of EBV-related malignancy, including posttransplant lymphomas. Tumors such as nasopharyngeal cell carcinoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, and Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) that fail to express some or all of the dominant CD8+-T-cell latent antigens still express EBNA1 (4, 15, 19). The EBNA1 protein contains a glycine-alanine repeat that prevents proper processing and presentation through the major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) pathway. Therefore, EBNA1 is poorly recognized by CD8+ T cells (36, 44, 45, 56). Although CD8+ CTLs have been raised against portions of EBNA1, these CTLs are unable to exert cytotoxicity against endogenous wild-type EBNA1 presented by LCLs (8, 9). However, several groups have recently cloned CD4+ T cells, some of which recognize EBNA1 presented by LCLs and BL cells (37, 43, 61, 90).

Our laboratory recently demonstrated that CD4+ T cells from healthy EBV-seropositive donors were necessary and sufficient to prevent in vitro proliferation and early outgrowth of CD23-positive B cells newly infected by EBV (57). Several questions remained unanswered about the mixed CD4+ effector cells present within the PBMC populations that limited B-cell proliferation. Were they directed against a specific EBV-encoded or -induced antigen? Was their recognition of infected cells mediated by MHC II presentation of viral peptides? How did they inhibit the early outgrowth of EBV-infected B cells? The availability of clonal populations of CD4+ T cells directed against EBNA1 enabled us to establish the principle that a clonal CD4+-T-cell population directed against a single EBV latent antigen can mediate early regression of infected B cells and allowed us to investigate their mechanism of action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Cell lines used included the EBV-transformed B-cell lines and EBV-positive Hodgkin's lymphoma cell line RPMI6666 listed in Table 1, the EBV-negative B-lymphoma line BJAB (39), and the EBV-positive marmoset cell line B95-8 (51). LCLs were generated by culturing PBMCs or CD3-depleted cells of healthy donors with supernatant of the B95-8 cell line in RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 μg of cyclosporine A/ml or 10 nM FK506 (Fujisawa), and antibiotics. HLA haplotypes of LCLs, determined by serotyping at the Yale Organ Transplant and Immunology Laboratory, are displayed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

HLA typing of LCLs

| Cell line | MHC class I

|

MHC class II

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | DR | DRw | DQ | |

| AB | 2, 25 | 7, 8 | 7, 17 | 52, 53 | 2, 3 |

| KB | 1, 30 | 7, 37 | 13, 15 | 51, 52 | 1 |

| AC | 1, 29 | 35, 38 | 1, 13 | 52 | 1 |

| BC | 30, 32 | 13, 44 | 4, 7 | 53 | 2, 3 |

| RD | 2, 3 | 13, 51 | 7, 11 | 52, 53 | 2, 7 |

| LG2 | 2 | 27 | 1 | 1, 5 | |

| CM | 2, 68 | 7, 44 | 4, 15 | 51, 53 | 3, 6 |

| CP | 2, 3 | 60, 62 | 4, 17 | 52, 53 | 2, 3 |

| PJ | 3, 29 | 35, 44 | 1, 7 | 53 | 1, 2 |

| JR | 23 | 35 | 1, 17 | 52 | 1, 2 |

| TY | 10, 11 | 27, 60 | 4, 15 | 51 | 1, 7 |

| RPMI6666 | 2, 3 | 7, 18 | 1, 5 | 6 | |

Analysis of cell surface molecules.

Viable cells were isolated on a Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient (ICN, Irvine, Calif.). Cells were washed and resuspended at 106 cells/ml in phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% FBS and 0.01% Na-azide. A mixture of saturating concentrations of two or three different fluorochrome-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibodies against human cell surface antigens was added for 45 min on ice. Cells were fixed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% paraformaldehyde. Antibodies included anti-CD3-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti-CD4-phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD8-PE, anti-CD8-Cychrome (Cyc), anti-CD14-PE, anti-CD19-PE, anti-CD19-Cyc, anti-CD23-FITC, and various anti-Vβ antibodies (gifts from D. Posnett, Cornell University, or purchased from Biosource International, Camarilla, Calif.). Isotype controls for background binding of the antibody molecules were a mixture of polyclonal murine immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1)-FITC, IgG1-PE, and IgG2-Quantum Red. Antibodies were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.), Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.), or DAKO (Carpinteria, Calif.). In the experiment illustrated below in Fig. 6, B-cell populations from two different donors were distinguished by the presence of HLA-B7 molecules on B cells from the HLA-DR7-negative donor and the absence of HLA-B7 molecules on B cells from the HLA-DR7-positive donor. The anti-HLA-B7-PE antibody was purchased from One Lambda (Canoga Park, Calif.). Staining was analyzed on a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.).

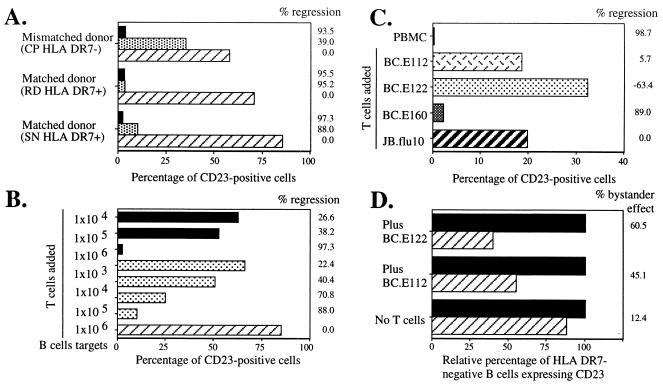

FIG. 6.

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones inhibit outgrowth of CD23+ B cells in EBV-infected cultures derived from MHC II-matched donors and from mismatched bystander B cells. Shown is the percentage of CD23+ B cells remaining after 18 days in culture. (A and B) CD4+-T-cell clone BC.E112 inhibited outgrowth of EBV-infected B cells from HLA-DR7+ but not HLA-DR7− donors. Equal numbers of autologous mixed CD4+ cells (solid bars), clone BC.E112 cells (stippled bars), or no T cells (hatched bar) were added to 106 EBV-infected B-cell targets/ml derived from HLA-DR7+ or HLA-DR7− donors on day 0. (B) Tenfold dilutions of autologous mixed CD4+ T cells (solid bars) or the BC.E112 clone (stippled bars) were added to 106 EBV-infected B-cell targets/ml (hatched bars) from an HLA-DR7+ matched donor on day 0. (C) Clone BC.E160 inhibited outgrowth of EBV-infected B cells from an HLA-DR4+ donor. Equal numbers of the HLA-DR7-restricted BC.E112 and BC.E122 clones, the HLA-DR4-restricted BC.E160 clone, or the JB.flu10 clone were added to 1.5 × 106 EBV-infected HLA-DR4+ B-cell targets/ml on day 0. Cultures of mixed PBMCs derived from the HLA-DR4+ B-cell donor and seeded at 1.5 × 106/ml were cultured as well (solid bar). (D) Bystander inhibition of outgrowth of HLA-DR7-negative mismatched B cells. Equal numbers of the BC.E112 clone or the BC.E122 clone were added to 106 HLA-DR7-negative mismatched EBV-infected B cell targets/ml (solid bars) on day 0. Parallel cultures contained both mismatched and 106 HLA-DR7-positive matched B-cell targets/ml (hatched bars) in the presence of clone BC.E122, clone BC.E112, or no T cells. Mismatched HLA-DR7-negative targets were selectively analyzed. Comparison of the hatched bars to the solid bars demonstrates the extent of inhibition exerted over mismatched CD23+ B-cell targets due to the presence of matched HLA-DR7-positive targets. The percent change which addition of MHC-matched B cells effected on CD23+ B-cell outgrowth is listed to the right of the graphs as percent bystander effect.

Intracellular staining.

Cells were stained for perforin protein, Fas ligand protein, or cytokines using the Cytofix/CytoPerm kit (Pharmingen) after culture with MHC-matched LCLs and Golgiplug containing brefeldin A (Pharmingen). For detection of perforin, clones were stimulated with autologous or MHC I- or II-matched LCLs for 12 h. Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) was added for the last 9 h of culture, and fixed cells were stained with PE-conjugated antiperforin murine antibody or control PE-conjugated polyclonal murine IgG2b antibody (Pharmingen). For detection of Fas ligand, clones were stimulated with autologous LCLs for 18 h; brefeldin A was added for the last 12 h of culture. Fixed cells were stained with a murine IgG isotype control or NOK-2 antibody directed against Fas ligand (Pharmingen) followed by staining with a FITC-conjugated antibody directed against the murine IgG constant region (Sigma). For detection of cytokines, cells were incubated with antibody to gamma interferon (IFN-γ; 1-D1K) and biotinylated antibody to interleukin-4 (IL-4; 12.1; MabTech, Nacka, Sweden) followed by incubation with anti-murine IgG-FITC antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) and avidin-Cyc (Pharmingen). After refixation in 1% paraformaldehyde, cells were analyzed by FACS.

RPAs.

LCLs were seeded at 3 × 105/ml, and T-cell clones were seeded at 5 × 105/ml in culture medium with 20 ng of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ml and 1 μM ionomycin (Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif.). Cells were harvested at 0, 6, 12, or 24 h after treatment with PMA and ionomycin. Total cellular RNA was isolated using the Qiashredder and RNeasy minikits (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Cytokine (hCK-1/2) or apoptosis pathway (Apo-3d/4) template sets were labeled with [α-32P]dUTP (NEN, Boston, Mass.) and hybridized with sample RNA using Riboquant RNase protection assay (RPA) reagents (Pharmingen). After an 18-h hybridization, protected RNA transcripts were separated on a 19:1 acrylamide-bis urea gel which was dried and exposed to Kodak X-OMat AR film.

DC preparation.

PBMCs were isolated from venous blood by centrifugation at 500 × g at room temperature over Ficoll-Hypaque lymphocyte separation medium (ICN). Positive selection for CD14+ cells was performed using murine anti-human CD14 antibody-conjugated microbeads, MACS depletion ferromagnetic matrix columns, and a VarioMacs separating magnet (Miltenyi-Biotec, Auburn, Calif.). CD14+ cells were grown in RPMI 1640 and 1% human plasma supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin B (61). Recombinant human IL-4 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor were added to culture wells on days 0, 2, and 4 to final concentrations of 500 U/ml and 1,000 U/ml, respectively. At the time of maturation on day 6, nonadherent immature dendritic cells (DCs) were transferred to new plates. Human IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and prostaglandin E2 were added to each well at final concentrations of 10 ng/ml, 1,000 U/ml, 10 ng/ml, and 1 μg/ml, respectively. After 48 h of culture in maturation medium, DCs were used or frozen. Cytokines were purchased from R&D (Minneapolis, Minn.); prostaglandin E2 was purchased from Sigma.

Presentation of EBNA1 and other antigens by DCs.

Antigens were introduced to DCs either as large proteins, small peptides, or through viral vectors. Escherichia coli-derived recombinant EBNA1 (rEBNA1; amino acids [aa] 458 to 641) or proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were added at a concentration of 10 μg/ml to DC cultures immediately prior to maturation (7, 16, 97). EBNA1-derived peptides 15 to 20 aa in length were added at 1 to 10 μM to mature DCs in serum-free medium and incubated for 1 h at 37°C (61). In some experiments mature DCs were infected with a vaccinia virus containing an EBNA1 construct lacking the glycine-alanine repeat (vvEBNA1ΔGA) or with a control vaccinia virus (vvTK−) at a multiplicity of infection of 2 (9, 36, 55, 56). Other mature DCs were infected with influenza virus X:31, A/Aichi/68 (H3N2) (Charles River Laboratories, North Franklin, Conn.) at an multiplicity of infection of 0.5. Virus and DCs were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in RPMI without serum and extensively washed in RPMI with pooled human serum prior to cocultivation with T cells.

Isolation and maintenance of CD4+-T-cell clones reactive to EBNA1 and influenza virus.

CD4+ PBMCs were isolated from venous blood of three donors (BC, AC, and JB cell lines) using anti-CD4-conjugated microbeads and magnetic selection (Miltenyi-Biotec). BC CD4+-T-cell lines were obtained after alternating stimulation with vvEBNA1ΔGA-infected DCs and autologous LCLs. DCs and LCLs were exposed to 3,000 and 20,000 rad, respectively, of gamma radiation in a 137Cs irradiator (Gammacell 1000; Nordion Int. Inc., Ontario, Canada). Twice, the line was enriched for EBNA1-reactive CD4+ T cells to a frequency of 1.5% using magnetic beads which isolated IFN-γ-secreting cells (Miltenyi Biotec) (61). AC CD4+-T-cell lines were obtained after two rounds of exposure to DCs pulsed with EBNA1 aa514-527 peptide. JB CD4+-T-cell lines were obtained by multiple rounds of stimulation with influenza virus-infected DCs and one enrichment via an IFN-γ secretion assay. Clonal T cells were obtained by seeding enriched populations at 10, 1, and 0.3 cells per well with 105 gamma-irradiated PBMCs (3,000 rad), 2 × 103 gamma-irradiated LCLs (20,000 rad), 150 U of IL-2 (Chiron, Emeryville, Calif.)/ml, and 1 μg of phytohemagglutinin (PHA)/ml in RPMI plus 8% pooled human sera (Labquip Ltd., Niagara Falls, N.Y.). Wells containing proliferating cells which originally were seeded with 1 or 0.3 T cells were tested in split-well enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assays for antigen specificity. Clones were expanded from frozen stock by cocultivation with irradiated PBMCs and LCLs, IL-2, and PHA. Clones were maintained by replacing half of the culture medium with fresh medium containing 300 U of IL-2/ml weekly. Approximately every 3 to 4 weeks, BC and AC clones were restimulated with gamma-irradiated autologous LCLs; the JB.flu10 clone was restimulated with autologous influenza virus-infected gamma-irradiated DCs.

Assessing the specificity of EBNA1- and influenza virus-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones.

The antigen specificity of BC clones was verified in ELISpot assays by response to DCs infected with vvEBNA1ΔGA versus that of DCs infected with vvTK−, the vector control, and by response to DCs loaded with rEBNA1 versus DCs loaded with PCNA. Antigen specificity of the AC clones was verified by their response to DCs loaded with rEBNA1 versus that of DCs loaded with PCNA or the response to DCs loaded with EBNA1 aa 514 to 527 versus that of DCs loaded with EBNA1 aa 481 to 500 or aa 551 to 570. Antigen specificity of the JB clone was verified by response to DCs infected with influenza virus versus that of DCs infected with vvTK−.

Maintenance and stimulation of an EBNA3A-reactive CD8+-T-cell clone.

CD8+ PBMCs were isolated from venous blood of an HLA-B8+ donor (MS cell line) using anti-CD8-conjugated MACS microbeads and magnetic selection (Miltenyi-Biotec). A CD8+-T-cell line was obtained after 2 weeks of stimulation with autologous LCLs. The line was enriched for EBNA3A-reactive CD8+ T cells over anti-PE MACS magnetic beads (Miltenyi-Biotec), which isolated cells bound to EBNA3A aa 325 to 333, HLA-B8-PE-conjugated tetramers (1, 12). Clonal CD8+ T cells were obtained by limiting dilution. Their antigen specificity was tested in split-well ELISpot assays. The MS.B11 clone was activated by exposure to HLA-B8-positive LCLs pulsed with 1 μM FLRGRAYGL peptide (10, 18, 34, 52, 64).

ELISpot assays for cytokine-secreting cells.

MAHA S45 plates (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) were coated with antibody to IFN-γ (1-D1K), antibody to IL-4 (82.4), or antibody to IL-5 (TRFK5) (MabTech) at 5 μg/ml in sodium bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.5. From 5 × 103 to 1 × 105 T cells were added per well. Freshly EBV-infected or mock-inoculated B cells, EBV-transformed LCLs, or DCs loaded with EBNA1 or control proteins were added to the T cells. Cells were cocultivated for 18 to 24 h in RPMI plus 5% pooled human sera, washed, and incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody; these included antibody to IFN-γ (7-B6-1), antibody to IL-4 (12.1), and antibody to IL-5 (5A10) (MabTech). Plates were washed and incubated with a preassembled avidin-peroxidase complex (Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.). Spots left by cytokine-secreting cells were developed by addition of stable diaminobenzidine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Spot-forming cells (SFCs) per well were counted using a stereomicroscope.

Antibody blocking of MHC interactions.

Anti-HLA-DR antibody L243 (42, 61) and anti-HLA-A, -B, and -C antibody w6/32 (6, 61) were isolated from hybridoma supernatant passed over a protein A column; the IgG fraction was eluted with 50 mM glycine, pH 3. The anti-HLA-DR antibody LB3.1 was a gift from Jordan Pober (20, 74). LCLs, or B cells 4 to 5 days after infection with EBV, were exposed to 25 to 100 μg of MHC-specific antibody/ml for 1 h at 37°C prior to cocultivation with T cells.

Assay for EBV-induced B-cell lymphoproliferation and T-cell control.

EBV and mock inocula were prepared as described previously from culture supernatants of the EBV-positive B95-8 cell line and the EBV-negative BJAB cell line, respectively (39, 51, 57). Subpopulations of PBMCs were selected as described previously (57). CD3-depleted populations were negatively selected using magnetic beads conjugated to murine anti-human CD3 antibodies (Dynal, Lake Success, N.Y.). Purified B cells were isolated by two steps of negative selection: all CD3+ cells were removed, and then the Dynal B-cell-negative isolation kit was used to deplete all remaining non-B cells. CD4+ T cells were positively selected on anti-CD4 antibody-conjugated microbeads and MACS selection columns (Miltenyi-Biotec). These selected populations and the desired concentrations of T-cell clones were then exposed to mock or EBV inoculum and cultured for 4 to 5 days for use in ELISpot assays or cocultivated for 16 to 18 days and analyzed for CD23 expression in regression assays. The number and percentage of CD19+ CD23+ cells were used as markers of immune control over EBV-exposed B cells (3, 11, 29, 57, 87).

Cytotoxicity assays.

A total of 107 LCLs/ml were labeled with 2.5 to 5 μg of calcein (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.)/ml (71, 89). Labeled targets were incubated from 3 to 19 h with T-cell clones in RPMI plus 10% FBS without phenol red. Fluorescence retained in the cell pellet was detected on a CytoFluor II (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.) with excitation at 480/25 nm and emission at 530/35 nm. Percent specific killing was calculated as follows: [(fluorescence maximal retention − fluorescence experimental well)/(fluorescence maximal retention − fluorescence minimal retention)] × 100. Maximal retention was determined by incubating the labeled targets alone or with MHC II-mismatched influenza virus-reactive CD4+ T cells. Minimal retention was determined by incubating targets in a lysis buffer of 50 mM sodium borate, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 9. Where indicated, T-cell clones were incubated with 10 μg of anti-Fas ligand antibody NOK-2 (Pharmingen)/ml, 10 μM brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich), or 100 nM concanamycin A (Fluka, Milwaukee, Wis.); LCLs were incubated with 250 ng of anti-Fas antibody ZB4 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.)/ml or 100 μM pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (Molecular Probes) for 2 h at 37°C prior to mixing the targets and T cells in culture. Transwell cytotoxicity experiments were conducted in 24-well plates containing inserts with a bottom membrane containing 3-μm pores to allow exchange of media and soluble factors (Transwell polycarbonate membrane; Costar, Cambridge, Mass.). Calcein retention from triplicate samples was assessed for each set of culture wells.

RESULTS

CD4+-T-cell clones raised against EBNA1 demonstrate a Th0 phenotype.

Our earlier experiments showed that mixed populations of CD4+ T cells controlled the activation and proliferation of B cells newly infected by EBV (57). The goal in the present experiments was to investigate the potential for CD4+-T-cell clones directed against a single EBV latency antigen, EBNA1, to establish immune control over the proliferation of B cells freshly infected with EBV. The use of cloned T cells with a single antigen specificity ensured that cells which recognized EBV antigens were mediating immune regression.

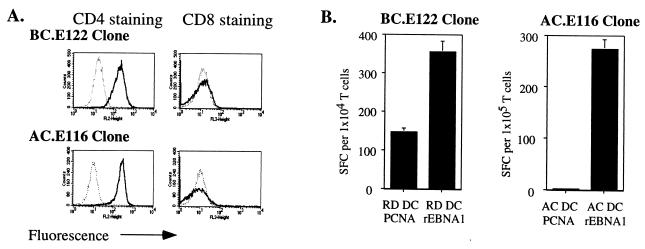

We studied the activity of two groups of CD4+-T-cell clones: one group of three clones was derived from an individual (BC) by alternating exposure to DCs expressing vvEBNA1ΔGA (aa 1 to 92, aa 323 to 641) (9) and autologous LCLs; a second group of two clones was derived from a different individual (AC cell lines) by exposure to DCs pulsed with a 14-aa EBNA1 peptide (aa 514 to 527) known to bind to HLA-DR1 (37, 38). All five clones were CD3 positive, CD4 positive, and CD8 negative (Fig. 1A and data not shown). FACS analysis of the T-cell antigen receptors showed that each BC clone expressed a single Vβ chain and that Vβ usage was unique to each clone (BC.E112, Vβ2; BC.E122, Vβ8; BC.E160, Vβ13.1) (61). Over months of repeated stimulation with MHC-matched LCLs or PHA, all the clones remained preferentially reactive to rEBNA1 (amino acids 458 to 641) provided to MHC II-matched DCs at the time of maturation (Fig. 1B and data not shown).

FIG. 1.

CD4+-T-cell clones recognize EBNA1 presented on MHC II-matched DCs. (A) FACS analysis of T-cell clones incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD4 (left panels; thick lines), CD8 (right panels; thick lines), or isotype control antibodies (thin, dotted lines). (B) IFN-γ secretion by a representative BC clone, BC.E122, and a representative AC clone, AC.E116, in response to DCs loaded with E. coli-derived rEBNA1 (aa 458 to 641) or PCNA proteins. HLA-DR7-matched (BC.E122 panel) or autologous (AC.E116 panel) DCs were loaded with protein at the time of maturation and seeded in ELISpot wells. Results represent the average of triplicate samples; standard errors of the means are shown.

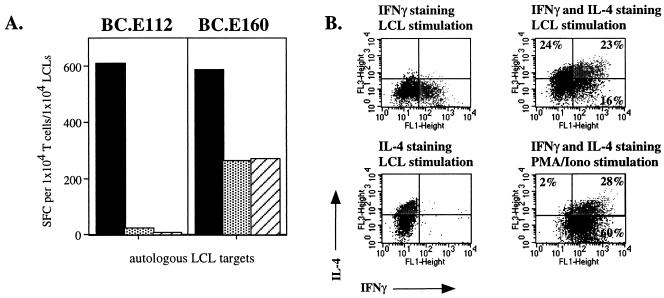

In order to characterize any effector functions of the EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones which might enable them to enact immune control over EBV infection, we analyzed their cytokine profiles. Although these clones were isolated for their ability to express IFN-γ in response to EBNA1, upon activation they expressed other Th1 cytokines and varying levels of Th2-type cytokine RNA transcripts and proteins (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Transcription of IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, TNF-β, and transforming growth factor β1, classic Th1 cytokines, was up-regulated in clone BC.E112 after stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. However, exposure to PMA and ionomycin also induced transcripts for the Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 (data not shown). Upon incubation with autologous and MHC II-matched targets, all BC clones secreted IL-4 and IL-5 at levels detectable by ELISpot in addition to large amounts of IFN-γ. However, the pattern of cytokine production by the BC.E112 and BC.E122 clones differed from that of clone BC.E160. In one experiment, clone BC.E112 yielded over 600 IFN-γ-secreting cells when stimulated with autologous LCLs, whereas only 23 BC.E112 cells secreted IL-4. In contrast, more than 260 cells from clone BC.E160 secreted IL-4 or IL-5 when stimulated with autologous or MHC II-matched LCLs in ELISpot assays (Fig. 2A and data not shown).

FIG. 2.

CD4+-T-cell clones raised against EBNA1 express both Th1- and Th2-type cytokines. (A) Secretion of IFN-γ (solid bars), IL-4 (stippled bars), and IL-5 (hatched bars) by 104 BC.E112 (left panel) or BC.E160 (right panel) cells in response to 104 autologous LCLs in ELISpot assays. SFC counts represent the average of duplicate samples. (B) Intracellular staining for production of IFN-γ (FL1 fluorescence) or IL-4 (FL3 fluorescence) by the BC.E160 cells. The BC.E160 clone was stimulated for 18 h with PMA and ionomycin or autologous LCLs. Plots on the left represent cells stained with antibody to IFN-γ alone (upper left plot, lower right quadrant) or antibody to IL-4 alone (lower left plot, upper left quadrant). Plots on the right represent cells stained with antibodies to both IFN-γ and IL-4 (upper right quadrants).

By staining for intracellular cytokines, we showed that activation with autologous LCLs led to production of IL-4 alone, IFN-γ alone, and IL-4 and IFN-γ together by BC.E160 cells (Fig. 2B). Global activation with PMA and ionomycin also induced many BC.E160 cells to secrete both IL-4 and IFN-γ. As individual cells concurrently secreted Th1- and Th2-type cytokines, the BC.E160 clone had a Th0 phenotype (24, 48, 63, 72). IFN-γ secretion by the cloned cells was used to assess the MHC restriction of activity in the following experiments.

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones recognize LCLs in an MHC class II-restricted manner.

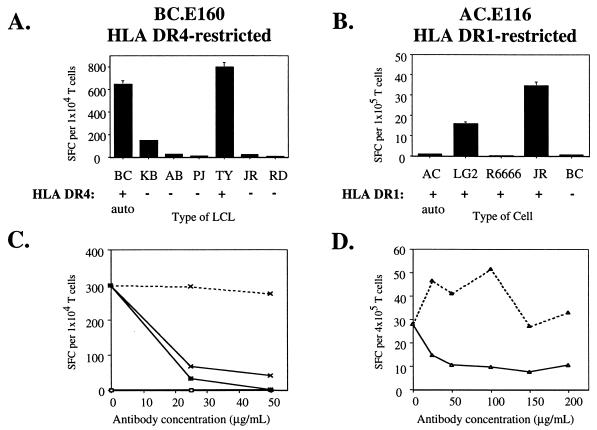

A panel of LCLs was used to identify B cells which could serve as MHC-matched targets in regression assays. Each of the three clones in the BC series recognized the autologous LCL and LCLs expressing matched MHC II molecules (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Clones BC.E112 and BC.E122 secreted IFN-γ in response to LCLs that expressed HLA-DR7, whereas clone BC.E160 secreted IFN-γ in response to LCLs that expressed HLA-DR4. The two clones in the AC series recognized two LCLs that expressed HLA-DR1 but failed to recognize two other HLA-DR1-positive cell lines, including the autologous LCL (Fig. 3B and data not shown). Moreover, the number of IFN-γ-secreting cells among the AC.E116 cells was at least 10-fold lower than the number reacting among the BC clones to MHC II-matched LCLs, despite the addition of 10-fold more LCLs and 10-fold more T cells per ELISpot well.

FIG. 3.

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones recognize MHC II-matched LCLs. (A and B) Recognition of LCLs bearing different MHC II molecules by EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones in IFN-γ ELISpot assays; 104 BC.E160 cells were added to 104 LCLs from donors matched or mismatched for the HLA-DR4 molecule (A), or 105 AC.E116 cells were added to 105 LCLs or an HLA-DR1-positive Hodgkin's lymphoma (RPMI6666) (B). SFC counts represent the average of triplicate samples; standard errors of the means are displayed. (C and D) Effect of antibodies against MHC I and MHC II on IFN-γ secretion by clones incubated with MHC II-matched LCLs in ELISpot assays. Antibodies to MHC I molecules (dotted lines), to MHC II molecules (solid line, open symbols), or a mixture of antibodies to MHC I and II (solid lines, filled symbols) were added at the indicated concentrations to LCLs and clones. LCL targets were HLA-DR4+/DR7− (x's) added at 5 × 103 per well to BC.E160 cells (C) or HLA-DR1+ (triangles) added at 5 × 104 per well to AC.E116 cells (D). SFCs represent the average of duplicate samples; data are representative of at least two experiments performed with each set of clones.

To explore further the role of MHC molecules in antigen recognition by the CD4+ clones, we carried out blocking experiments using antibodies directed against MHC I and MHC II molecules. The ability of all three BC clones to recognize MHC II-matched LCL targets was markedly inhibited by addition of the L243 or LB3.1 antibodies directed against HLA-DR molecules (Fig. 3C and data not shown). By contrast, addition of w6/32 antibodies against MHC I had little inhibitory effect. The combination of antibodies to MHC I and II together was not significantly more inhibitory than antibodies to MHC II alone. Antibodies to MHC II, but not to MHC I, also blocked the reactivity of clone AC.E116 to an HLA-DR1-matched LCL (Fig. 3D). In summary, IFN-γ secretion in response to a panel of LCLs and the blocking effects of antibodies confirmed that the CD4+-T-cell clones recognized antigen in conjunction with specific MHC II molecules.

CD4+-T-cell clones reactive to EBNA1 recognize B cells newly infected by EBV in an MHC II-restricted manner.

In the previously described experiments we explored the ability of CD4+-T-cell clones to recognize EBV-transformed LCLs. LCLs differ dramatically in surface markers, adhesion molecules, and viral protein expression from the heterogenous population of B cells found in the early stages of infection by EBV (3, 5, 66, 88). Therefore, we investigated whether the same EBNA1-reactive clones that recognized LCLs also recognized B cells freshly infected with EBV.

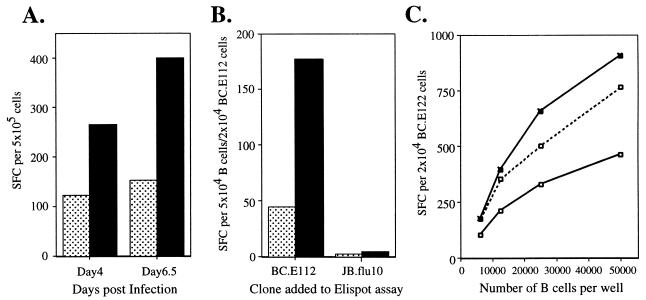

The number of IFN-γ-secreting cells among the BC.E112 (Fig. 4A and B) and BC.E122 (Fig. 4C and data not shown) clones were two to three times greater in the presence of EBV-infected B cells than in the presence of B cells exposed to a mock inoculum. Cells from clones BC.E112 and BC.E122 secreted IFN-γ in response to B cells that had been infected with EBV for only 4 days. This reactivity to early EBV infection was observed when the BC.E112 clone was cocultured with the B cells from the time of infection (Fig. 4A) as well as when the B cells were infected separately for 4 days and then mixed with the BC.E112 clone for the 18-h duration of the ELISpot assay (Fig. 4B). Cells of a CD4+-T-cell clone directed against influenza virus, JB.flu10, did not respond to EBV-infected or mock-inoculated B cells, although the clone was capable of secreting IFN-γ in response to influenza virus-infected DCs (Fig. 4B and data not shown). The IFN-γ response of the BC clones to freshly EBV-infected B cells was mediated primarily through MHC II molecules. In ELISpot assays, antibody to MHC II decreased the number of IFN-γ-secreting BC.E112 and BC.E122 cells much more effectively than did antibody to MHC I (Fig. 4C and data not shown).

FIG. 4.

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones secrete IFN-γ in response to B cells newly infected with EBV. (A) IFN-γ secretion in an ELISpot assay by a 2:1 mixture of clone BC.E112 cells and freshly EBV-infected (solid bars) or mock-inoculated (stippled bars) B cells after coculture for 4 and 6.5 days. (B) IFN-γ secretion by clone BC.E112 and clone JB.flu10 cells exposed to B cells for the 18-h duration of an ELISpot assay. The B cells had been cultured with EBV (solid bars) or a mock inoculum (stippled bars) for 4 days prior to exposure to the clones. Results represent the average of duplicate samples and are representative of at least two experiments performed on B cells from different donors. (C) IFN-γ secretion by clone BC.E122 in response to purified B cells cultured with EBV for 4 days. B cells were incubated with antibodies against MHC I or II at 100 μg/ml before addition of the T-cell clones. No antibody addition (solid line, filled symbols), addition of antibody to MHC I (dashed line, open symbols), and addition of antibody to MHC II (solid line, open symbols) are represented.

CD4+-T-cell clones raised against EBNA1 prevent proliferation and early outgrowth of EBV-infected CD23+ targets derived from the autologous donor.

The capacity of memory T cells from an EBV-seropositive donor to prevent the outgrowth of EBV-infected cells is termed regression (41, 53, 54, 69, 70). In previous work our group demonstrated that an early event in regression is the capacity of a mixed population of memory CD4+ T cells to inhibit proliferation of EBV-infected CD23+ B cells (57). Since CD23 synthesis is regulated by the EBV latent protein EBNA2, a transcription factor essential to B-cell immortalization, CD23 expression correlates with transformation of B cells by EBV (3, 11, 29, 87). Depletion of CD3+ T cells or CD4+ T cells, but not of CD8+ T cells, resulted in the accumulation of CD23+ B cells 10 to 21 days after EBV infection (57). A mixed population of CD4+ T cells isolated from a seropositive donor prevented the accumulation of CD23+ B cells when added to CD3-depleted EBV-infected targets.

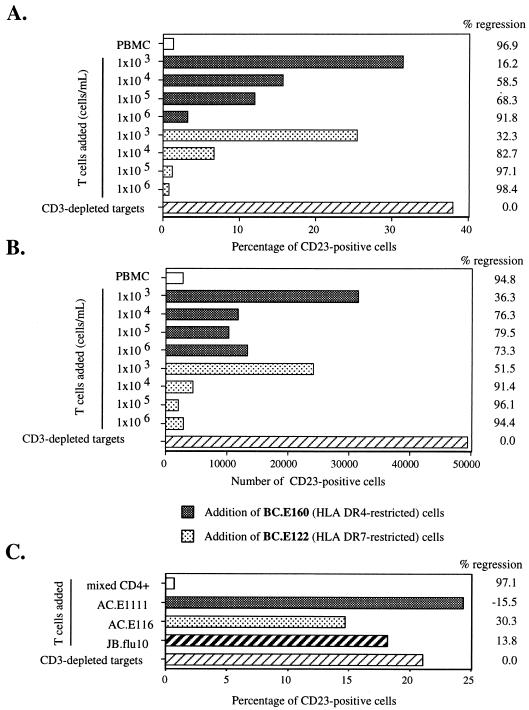

The antigen specificity of these polyclonal CD4+ T cells was likely to be diverse and could include a multitude of unknown viral and cellular targets. Therefore, we asked whether CD4+-T-cell clones reactive to EBNA1, and capable of secreting IFN-γ in response to newly EBV-infected B cells, would also enact regression. Addition of the BC.E122 (HLA-DR7-restricted) or BC.E160 (HLA-DR4-restricted) clone to CD3-depleted targets from the autologous donor at the time of EBV infection in vitro markedly diminished both the percentage and number of CD23+ B cells remaining after 18 days in culture (Fig. 5A and B). The numbers of CD23+ B cells remaining after addition of T-cell clones at a clone-to-target cell ratio of 1:1 were similar to those remaining in the mixed PBMC cultures. Based on titration, the BC.E122 clone was slightly more effective than the BC.E160 clone at inducing regression. The capacity of the clones to enact regression decreased as fewer T cells were added, but significant effects on the number and percentage of CD23+ B cells remaining after 18 days were evident even at a T cell-to-target cell ratio of 1:100.

FIG. 5.

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones from donor BC reduce outgrowth of CD23+ B cells in EBV-infected cultures derived from the autologous donor. Shown are the percentage (A and C) and number (B) of CD23+ B cells remaining after 16 to 18 days in culture. (A and B) Serial 10-fold dilutions of two clones, the HLA-DR4-restricted BC.E160 (gray bars) and the HLA-DR7-restricted BC.E122 clone (stippled bars), were added to 106 EBV-infected CD3-depleted PBMCs/ml from autologous donor BC cells. Hatched bars represent the outgrowth of CD3-depleted target cells without the addition of T-cell clones at the time of infection on day 0. White bars represent outgrowth in cultures of EBV-infected, autologous, mixed PBMCs. (C) AC clones fail to inhibit CD23+ B-cell outgrowth. Equal numbers of the AC.E116 and AC.E1111 clones, the JB.flu10 clone, or mixed autologous CD4+ T cells were added to 1.5 × 106 EBV-infected CD3-depleted PBMCs/ml from donor AC cells on day 0. The percent change which addition of T cells effected on CD23+ B-cell outgrowth is listed to the right of the graphs as the percent regression.

Neither AC clone was capable of enacting regression in a culture of autologous EBV-infected CD3-depleted cells; however, mixed CD4+ T cells from the AC donor mediated regression. The AC clones had the same effect as an MHC-mismatched CD4+-T-cell clone that recognized influenza virus-infected cells (Fig. 5C). These results show that not all EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones were competent to mediate regression and that secretion of low levels of IFN-γ in response to autologous LCLs correlated with poor performance in regression assays (Fig. 3).

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones enact regression on MHC II-matched, EBV-infected B-cell targets from multiple donors.

We next investigated whether the BC clones could exert immune control over EBV-infected B cells from nonautologous, HLA-DR7-negative and -positive donors and from HLA-DR4-negative and -positive donors. Purified B cells were used in these experiments in order to avoid potential interactions of the CD4+ clones with natural killer cells that might be present in CD3-depleted target cell cultures. Addition of clone BC.E112 cells to HLA-DR7-positive matched B cells from two different donors resulted in regression. The addition of HLA-DR7-restricted BC.E112 or BC.E122 did not significantly impact the outgrowth of CD23+ B cells from HLA-DR7-negative donors (Fig. 6A and C). Similarly, the HLA-DR4-restricted BC.E160 clone exerted immune control over B cells from an HLA-DR4-positive donor, whereas the BC.E112, BC.E122, and JB.flu10 clones did not (Fig. 6C).

When mixed CD4+ T cells or clone BC.E112 was added to cultures at a T cell-to-B cell ratio of 1:1, the two sets of T cells were similar in their ability to cause regression (Fig. 6B, data for 106 T cells added/ml). However, when seeded at lower cell numbers, the clones were approximately 10-fold more effective in their ability to cause regression than the mixed CD4+ population: 105 mixed CD4+ T cells/ml enacted a degree of regression similar to that seen with 104 BC.E112 cells/ml.

EBNA1-reactive T-cell clones BC.E112 and BC.E122 enact “bystander” control over newly EBV-infected B cells from MHC II-mismatched donors.

IFN-γ secretion (Fig. 3) and regression assays (Fig. 5 and 6A to C) demonstrated that only EBV-infected targets expressing a matched MHC II molecule could activate EBNA1-reactive clones. Once activated, however, the clones exerted their effects on targets that were not MHC matched (Fig. 6D). To demonstrate this phenomenon, B cells from an HLA-DR7-positive and an HLA-DR7-negative donor were exposed individually or in coculture to the HLA-DR7-restricted BC.E112 and BC.E122 clones. CD23 expression within the HLA-DR7-negative mismatched B-cell population was selectively analyzed. The addition of HLA-DR7-positive matched B cells in the presence of the BC.E112 or BC.E122 clone resulted in a 45 to 60% decrease in CD23 expression on the mismatched B cells. This decrease was of the same magnitude as the 42 to 47% decrease effected by the BC.E112 and BC.E122 clones on the CD23 expression of matched B cells in this same experiment (Fig. 6D and data not shown). These results indicate that once the EBNA1-reactive CD4+ clones were activated by MHC II-matched EBV-infected B cells, MHC-mismatched EBV-infected B cells became targets for bystander regression.

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones lyse MHC II-matched LCLs and mismatched bystander LCLs.

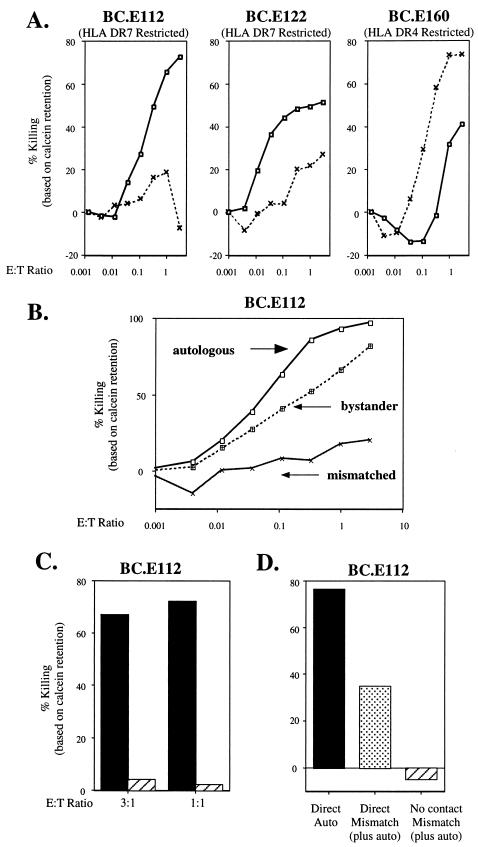

IFN-γ secretion by the EBNA1-reactive CD4+ clones in response to LCL targets was a marker of their ability to cause regression of newly EBV-infected B cells. Therefore, to elucidate potential mechanisms used by the EBNA1-reactive clones to exert regression, we investigated whether they possessed cytolytic activity against LCLs. In a calcein release assay, the BC.E112 clone caused losses of 70 and 72% of retained fluorescence from autologous and HLA-DR7-matched LCLs, respectively, at an effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 3:1 (Fig. 7A and data not shown). The BC.E112 clone caused minimal background lysis of HLA-DR7-mismatched LCLs. BC.E122 and BC.E160 lysed MHC II-matched LCL targets with similar efficacy. The BC.E112 clone effected significant lysis of autologous LCLs during a short 5-h incubation; the other two BC clones required 18 h of incubation with the targets before killing became evident (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones are cytotoxic following direct contact with MHC II-matched LCLs and with mismatched bystander LCLs. (A) Retention of calcein dye in MHC II-matched and -mismatched LCLs exposed for 19 h to each of three BC clones. LCL targets were HLA-DR4−/DR7+ (solid line, squares) or HLA-DR4+/DR7− (dashed line, x's). (B) Retention of calcein dye 18 h after addition of the BC.E112 clone to autologous LCLs (solid line, squares), MHC-mismatched HLA-DR7− LCLs (solid lines, x's), or a combination of autologous and mismatched LCLs (dotted line, filled squares). In cultures where LCLs were combined, only the HLA-DR7− mismatched LCLs were labeled with calcein and analyzed. (C) Cytotoxicity measured by retention of calcein dye by autologous LCLs after 18 h of direct contact with the BC.E112 clone (solid bars) or by autologous LCLs separated from the same BC.E112-LCL cocultures by a porous membrane (hatched bars). (D) Cytotoxicity against autologous LCLs (solid bars) or against bystander MHC II-mismatched LCLs (stippled bars) after 18 h of direct contact with clone BC.E112 or against the same mismatched LCLs separated from BC.E112-autologous LCL cultures by a porous membrane (hatched bar).

In a phenomenon similar to that of bystander regression, the presence of MHC-matched targets rendered MHC-mismatched LCLs susceptible to bystander lysis by EBNA1-reactive clones (2). Incubation of dye-loaded autologous LCLs with a mismatched LCL did not alter the efficient lysis of the autologous LCL by BC.E112 (Fig. 7B). However, such coincubation resulted in lysis of dye-loaded mismatched LCLs that were not lysed when incubated with BC.E112 in the absence of the autologous LCL. Bystander killing of the mismatched LCL was less efficient than killing of the autologous LCL. At an E:T ratio of only 1:10, BC.E112 cells released 63% of dye from autologous LCLs; in contrast, BC.E112 cells were required at an E:T ratio of 1:1 to release dye from 66% of the mismatched bystander LCLs.

To investigate whether cytotoxicity could be mediated by soluble factors, such as IFNs or TNFs secreted into the culture supernatant, we performed calcein release experiments on BC clones and LCL targets in direct contact or on LCL targets separated from the activated clones by a porous membrane. The data displayed in Fig. 7C demonstrate lack of cytolysis in autologous LCL targets which were separated by a transwell membrane from autologous LCLs in direct contact with clone BC.E112. Similarly, MHC II-mismatched LCLs, which were subject to bystander lysis when in direct contact with autologous LCLs and clone BC.E112, were not lysed when they were separated by a membrane from activated T-cell cultures (Fig. 7D).

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones do not use perforin to lyse LCLs.

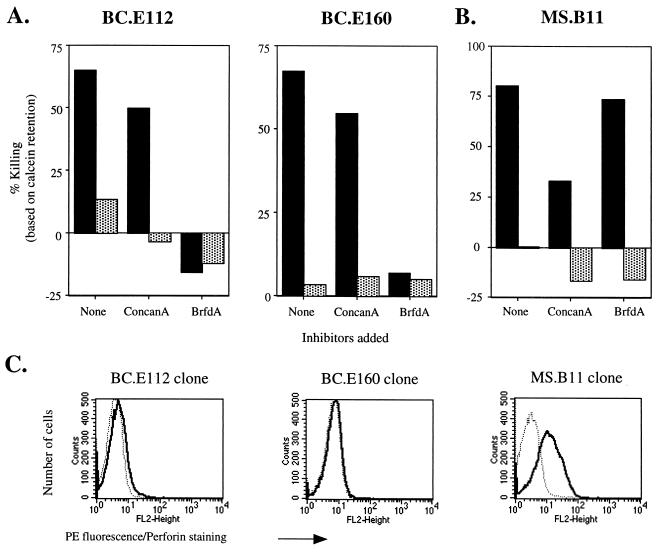

Classic mechanisms of contact-dependent T-cell-induced death include release of preformed vacuolar granzymes and perforin into an intracellular space and up-regulation on the cell surface of molecules like Fas ligand and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) (35, 58, 77, 82). These two effector pathways can be differentiated by the selective action of concanamycin A and brefeldin A (31, 33, 46, 79). Incubation with concanamycin A, which raises the pH in intracellular vacuoles and inactivates perforin, did not inhibit the killing of autologous LCLs by the BC.E112 or BC.E160 clone (Fig. 8A). In contrast, exposure of the clones to brefeldin A, which prevents progression of newly synthesized proteins through the Golgi apparatus, completely blocked the clones' ability to lyse autologous LCLs. Using the MS.B11 CD8+-T-cell clone specific for EBNA3A, we verified that concanamycin A, but not brefeldin A, inhibited classical CD8+-T-cell perforin-mediated killing of an antigen-loaded LCL in a 3-h calcein retention assay (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones do not utilize perforin to induce cytolysis of LCLs. (A) Cytotoxicity against autologous (solid bars) or MHC II-mismatched (stippled bars) LCL targets after 18 h in culture with BC.E112 or BC.E160 cells at a 1:1 ratio. Prior to exposure to LCLs, clones were incubated with concanamycin A (ConcanA), brefeldin A (BrfdA), or culture medium alone (none). (B) Loss of calcein dye by MHC I-matched LCL targets with (solid bars) or without (stippled bars) addition of EBNA3A antigenic peptide after 3 h in culture with MS.B11 CD8+-T-cell clones at a 1:1 ratio. (C) Intracellular staining with antibody to perforin. BC EBNA1-reactive CD4+ clones were stimulated with autologous LCLs; the EBNA3A-specific CD8+-T-cell clone MS.B11 was stimulated with peptide-loaded, MHC I-matched LCL (solid lines). Staining with a PE-conjugated isotype control is shown by the dotted lines.

The inability of concanamycin A to inhibit the lytic activity of the CD4+ clones correlated with their lack of perforin mRNA and protein. As detected by RPA, PMA and ionomycin up-regulated transcripts for granzymes A, B, and H but did not up-regulate perforin mRNA in the BC.E112 clone (data not shown). Similarly, antibodies that detected perforin in antigen-stimulated CD8+-T-cell clone MS.B11 did not bind more avidly than an isotype control antibody to LCL-stimulated CD4+ BC T-cell clones (Fig. 8C and data not shown).

Fas and Fas ligand contribute to lysis of LCLs by EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones.

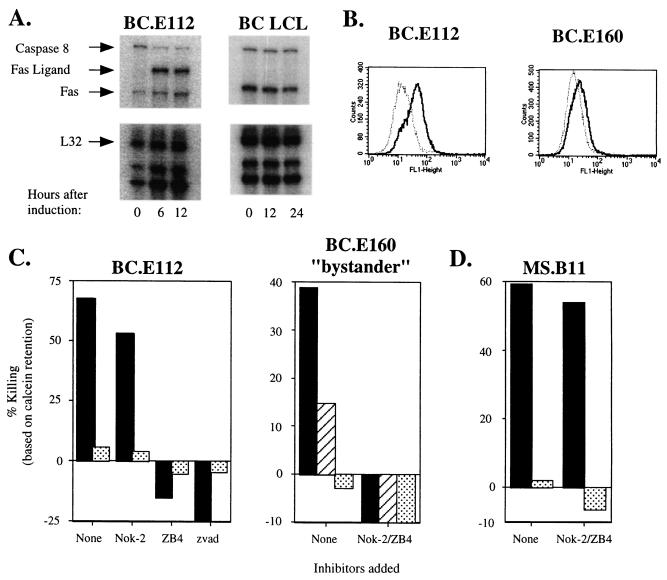

The inhibition of killing by addition of brefeldinA or by physical separation behind a membrane suggested that the CD4+-T-cell clones employed a cell surface protein such as Fas ligand to effect LCL death. By RPA, we demonstrated that treatment of clone BC.E112 with PMA and ionomycin induced Fas ligand mRNA (Fig. 9A). Fas ligand protein was also up-regulated in the BC clones after incubation with PMA and ionomycin or with MHC II-matched LCLs (Fig. 9B and data not shown). In addition, the BC.E112 T-cell clone and the autologous LCL constitutively expressed Fas transcripts (Fig. 9A). All the CD4+-T-cell clones and target LCLs expressed Fas protein on their surface (data not shown). Incubation with the ZB4 neutralizing antibody, which binds Fas and blocks binding of Fas ligand, prevented loss of calcein fluorescence when the autologous LCL was exposed to either the BC.E112 or the BC.E160 clone (Fig. 9C and data not shown). Exposure of T cells to the NOK-2 antibody against Fas ligand also inhibited killing, particularly by the BC.E160 clone. Combination of the NOK-2 and ZB4 antibodies completely prevented lysis of MHC-matched LCLs and of bystander MHC-mismatched LCLs incubated in the presence of matched targets. In contrast, lysis of antigen-loaded LCLs by the CD8+ MS.B11 clone was minimally inhibited by a combination of NOK-2 and ZB4 antibodies (Fig. 9D). Preincubation of the LCLs with the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk also eliminated lysis by the BC CD4+-T-cell clones (13, 30) (Fig. 9C). Thus, the CD4+ BC T-cell clones utilized Fas-Fas ligand interactions and not soluble factors or perforin to induce apoptosis in matched LCLs and mismatched bystander LCLs.

FIG. 9.

EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones express Fas ligand (FasL) when activated and induce cytolysis of LCLs via a Fas and FasL interaction. (A) RPA performed at the indicated times after stimulation of the BC.E112 clone or autologous LCLs with PMA and ionomycin. Relevant transcripts are indicated by arrows. L32 represents a housekeeping gene. (B) Intracellular staining with NOK-2 antibody to Fas ligand expressed by the BC clones after stimulation with autologous LCL (solid lines). Staining with an isotype control antibody and the secondary FITC-conjugated anti-murine IgG antibody is shown by the dotted lines. (C) Loss of intracellular calcein dye by autologous LCLs (solid bars) or MHC II-mismatched (stippled bars) LCL targets alone after 18 h in culture with BC.E112 clones (E:T ratio of 2:1) or BC.E160 clones (E:T ratio of 1:1). The panel entitled “BC.E160 bystander” compares killing of autologous LCLs (solid bars), MHC II-mismatched LCLs (stippled bars), and MHC II-mismatched LCLs in the presence of autologous LCLs (hatched bars). (D) Loss of calcein dye by MHC I-matched, antigen-loaded (solid bars) or nonloaded (stippled bars) LCLs after 3 h in culture with CD8+-T-cell clone MS.B11 at an E:T ratio of 1:1. In panels C and D, T cells and LCLs were incubated with culture medium (none), the NOK-2 antibody to Fas Ligand, the ZB4 neutralizing antibody to Fas, a combination of both antibodies (NOK-2/ZB4), or the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk.

DISCUSSION

We extensively characterized a set of three CD4+-T-cell clones reactive to EBNA1 that inhibit the activation and early outgrowth of human B lymphocytes following infection in vitro with EBV. These results contribute to the growing list of antiviral activities mediated by CD4+ T cells and establish the principle that CD4+ T cells directed against one viral protein are competent to mediate early immune control over EBV-induced B-cell outgrowth. The clones are cytotoxic to autologous and MHC II-matched lymphoblastoid cells. Cytotoxicity requires cell-to-cell contact and is mediated by Fas/Fas ligand interactions. In both regression and cytotoxicity assays, the CD4+-T-cell clones exerted bystander effects in which MHC II-mismatched B-cell targets were inhibited from outgrowth or lysed, but only in the presence of MHC II-matched B-cell targets. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells directed against EBNA1 may assume a role in T-cell immunoprophylaxis or immunotherapy of B-cell LPDs. They are of particular importance since EBNA1 is expressed in every EBV-associated malignancy and is not well recognized by CD8+ T cells (8, 37, 68).

Characterization of cytotoxic CD4+-T-cell clones reactive to EBNA1.

Three CD4+-T-cell clones were isolated from a single individual (BC line) by virtue of their capacity to secrete IFN-γ following alternate exposure to autologous DCs infected with a vaccinia virus vector expressing EBNA1 and autologous EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cells. The published literature contains contradictions as to whether Th1 or Th2 cytokines dominate the responses of mixed CD4+ T cells to EBNA1 (7, 61, 83). Our novel finding is that BC clones expressed cytokines of both Th1 (IFN-γ) and Th2 (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13) types following application of T-cell activation stimuli (Fig. 2). BC.E160 secreted large amounts of IL-4 and IL-5, whereas the cytokine responses of BC.E112 and BC.E122 were skewed toward Th1-type cytokines. Since the BC.E160 clone expressed both Th1 and Th2 cytokines in the same cell, it can be classified as Th0. All three clones caused regression and cytolysis to the same extent (Fig. 5 to 9). Neither of these functional effects could be reproduced by CD4+-T-cell clones separated from targets by membrane filters. Therefore, while cytokine expression reflects the differentiation and activation state of the clones and helps to classify them, the secreted cytokines themselves are not likely to be essential effector mechanisms.

Inhibition of proliferation of EBV-infected B cells by CD4+-T-cell clones reactive to EBNA1.

The capacity of the clones to exert regression was assessed with our newly developed techniques which measure early outgrowth of CD23-positive B cells (57, 60). The number and percentage of CD23+ B cells have been shown to correlate with the number of EBNA-positive, EBV-infected cells detected by immunofluorescence in cultures maintained for 2 weeks after exposure in vitro to EBV. Cell-mediated immunity as measured by early outgrowth of CD23+ B cells and immunity measured by longer-term outgrowth assays both exhibit a dependence on T cells, a sensitivity to immunosuppressive drugs, a dependence on initial cell density, and a lack of dependence on macrophages (57, 69). Classical outgrowth assays have always emphasized the role of CD8+ T cells (41). However, by assaying for CD23+ B-cell outgrowth at 2 to 3 weeks after infection, we elucidated a role for CD4+ T cells in immune control over EBV (57). Therefore, we chose to measure CD23+ B-cell percentages to investigate the effector functions of CD4+ T cells reactive to EBNA1.

When added to freshly infected B cells, even at a ratio of 1 T cell to 100 B-cell targets, the three BC clones markedly reduced the outgrowth of CD23+ B cells (Fig. 5 and 6). The specificity of regression mediated by the CD4+-T-cell clones was established in several ways: (i) at early times after infection, three- to fourfold more clones responded to EBV-infected B cells by secretion of IFN-γ than reacted to mock-infected B cells (Fig. 4). (ii) CD4+-T-cell clones matched for MHC II enacted regression, whereas those mismatched for MHC II did not (Fig. 6A and C). (iii) A CD4+-T-cell clone raised to a non-EBV antigen, i.e., proteins from influenza virus, did not react to EBV-infected B cells (Fig. 4B), nor did it inhibit outgrowth of CD23+ B cells following EBV infection (Fig. 6C).

At an E:T ratio of 1:1, mixed CD4+ T cells were slightly more efficient inhibitors of B-cell proliferation than were the CD4+-T-cell clones (Fig. 6A and B). However, the BC.E112 clone markedly inhibited B-cell proliferation at an E:T ratio of 1:10, whereas the mixed cells were effective only at an E:T ratio of 1:1. Thus, the clonal population was 10-fold more active than autologous mixed CD4+ T cells. Since the number of EBV antigen-specific T cells present in the mixed CD4+-T-cell population is likely to be significantly lower than in the clonal population, their somewhat greater activity at high E:T ratios suggests three hypotheses that need to be explored in future experiments: (i) The mixed population is likely to include CD4+ T cells that recognize EBV antigens other than EBNA1. The other antigens may provide stronger stimulation. (ii) The mixed CD4+-T-cell population may include cells, reactive to EBNA1 or other EBV antigens, with very-high-affinity T-cell antigen receptors. These high-affinity T cells may not have been cloned. (iii) The EBV-specific mixed CD4+-T-cell population may employ more-potent effector mechanisms or may expand more rapidly to control B-cell outgrowth than do the clones.

Cytotoxic activity of EBNA1-reactive clones.

A number of mechanisms could account for the capacity of the BC clones to inhibit proliferation of CD23+ B cells following EBV infection. These include down-regulation of CD23 from the surface of B cells, noncytotoxic inhibition of proliferation of EBV-infected CD23+ B cells, and B-cell lysis during virus reactivation and release, as well as classical lysis (17). Modes of lysis employed by various EBV-specific CD4+ T cells include release of perforin and granzymes, granulysin release, and up-regulation of surface Fas ligand and TRAIL molecules (85, 86, 93, 94). The ability of brefeldin A to block cytotoxicity by the BC clones, the expression of Fas ligand on the surface of activated clones and Fas on target cells, and the neutralizing effect of antibodies to Fas and Fas ligand all support the hypothesis that the mechanism of cytotoxicity of the BC clones was apoptosis initiated by Fas and Fas ligand interactions.

Our experiments appear to exclude contributions to cytolytic activity of BC clones by several mechanisms other than Fas and Fas ligand interactions. Cytotoxicity mediated by a perforin-granzyme mechanism was excluded by showing that concanamycin A, an inhibitor of vacuolar proton pumps which leads to perforin degradation, did not block cytotoxicity of the BC clones towards MHC II-matched target cells (Fig. 8A) (33). Moreover, the CD4+-T-cell clones did not express perforin protein upon activation, whereas a cytotoxic CD8+-T-cell clone did (Fig. 8C). Cytotoxicity did not appear to be mediated by a soluble cytokine. Transfer of supernatants from mixed cultures of CD4+-T-cell clones and matched LCLs to a fresh LCL did not transfer lytic activity (data not shown). LCL cells separated by a membrane from mixtures of CD4+-T-cell clones and activating LCLs were not lysed (Fig. 7 and 9). Since our data demonstrate that the clones are cytotoxic to LCL through Fas and Fas ligand interactions, it seems likely that a similar mechanism is responsible for their activity in the regression assay against freshly EBV-infected B cells.

Bystander effect.

We suggest a plausible mechanism for the bystander effect seen in early regression and cytotoxicity assays. A T-cell clone activated by encounter with an MHC II-matched target up-regulates Fas ligand on its surface. Upon interaction with a susceptible mismatched cell that expresses Fas, the T-cell clone would be cytotoxic. The physical interaction of an activated clone with a mismatched target would be less likely to occur, and the interaction would not be augmented or sustained by cognate interactions between the T-cell antigen receptor and MHC II loaded with antigenic peptide. Therefore, bystander cytotoxic effects would be less efficient than MHC II-matched interactions. This model gains support from our experimental observations that antibodies to Fas and Fas ligand also inhibit the bystander reaction (Fig. 9C). Moreover, bystander cytotoxicity effects also required cell-to-cell contact: MHC II-mismatched LCL cells separated by a membrane from a mixture of CD4+-T-cell clones and MHC II-matched LCLs were not lysed.

Some EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones do not mediate regression.

CD4+-T-cell clones are often generated by exposure to EBNA1 peptides (37, 43). We studied two EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones derived from a single individual (AC line) by exposure to autologous DCs pulsed with an EBNA1 peptide (aa 514 to 527) that was known to be presented by the HLA-DR1 molecule (37). The AC clones could not mediate regression; their lack of activity in the regression assay was similar to a CD4+-T-cell clone directed against influenza virus (Fig. 5C). Although the AC clones secreted copious amounts of IFN-γ in response to autologous DCs loaded with recombinant EBNA1 protein (Fig. 1B), their response to MHC II-matched LCLs was 300 times weaker than that of BC clones exposed to comparable targets. Remarkably, the AC clones failed to secrete IFN-γ when exposed to the autologous LCL (Fig. 3A and data not shown). These results suggest that CD4+-T-cell clones, such as AC, that do not secrete cytokines in response to the autologous LCL are not likely to inhibit outgrowth of freshly infected B cells.

Further work is needed to explore reasons for the dramatic differences in behavior between the BC and AC clones. One explanation is that the EBNA1 peptide (aa 514 to 527) antigen recognized by the AC clones was not efficiently generated or presented by MHC II molecules on LCL. The poor, or even absent, response of the AC clones to MHC II-matched LCL is consistent with this explanation. Another related explanation may lie in the relatively low affinity of the T-cell antigen receptor on the AC clones. The T-cell receptor affinity may be low for any HLA-DR1 molecule containing the EBNA1 aa 514 to 527 peptide, even MHC complexes loaded exogenously, or only for the HLA-DR1/EBNA1 aa 514 to 527 complex which is selected by intracellular processing of EBNA1 (65). Support for these hypotheses stems from our preliminary experiments indicating that the AC.E116 clone secreted IFN-γ and lysed autologous LCLs after they were pulsed with large amounts of the EBNA1 aa 514 to 527 peptide (data not shown).

The AC clones were derived by exposure to high levels of peptide loaded on the surface of DCs, whereas the BC clones were selected for their response to more physiologic levels of EBNA1 antigen presented by vaccinia virus-infected DCs and by LCLs. The second method of generation may lead to isolation of clones with higher-affinity T-cell antigen receptors. In studies of CD8+ T cells reactive to melanoma antigens, sorting for populations that exhibit high levels of tetramer binding has proven useful for isolation of cytotoxic CD8+-T-cell clones (95). Such a T-cell receptor affinity selection step or exposure to targets with physiological levels of antigen, such as LCLs, may be necessary to raise clones capable of preventing EBV-induced B-cell outgrowth. Our findings suggest that heterogeneity exists in the antigen affinity of polyclonal EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell populations. This heterogeneity could result from T-cell priming in vivo by an antigen-presenting cell other than an LCL or EBV-infected B cell. High- or low-affinity clones may be preferentially expanded, depending on the stimulation conditions.

Potential clinical applications of EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones.

Progression to transformation and establishment of immortal EBV-positive cell lines in vitro correlates with expansion of CD23+ B cells; similarly, the progression to EBV-associated LPD is characterized by infection of new B-cell targets and malignant expansion of the CD23+-B-cell population. An EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clone, which has been shown by in vitro experiments such as we describe to be competent to prevent early outgrowth of CD23+ B cells newly infected with EBV (Fig. 5 and 6), may prove useful in preventing CD23+ EBV+ B-cell lymphomas in vivo. A panel of such CD4+-T-cell clones might be raised to recognize EBNA1 presented on different MHC II molecules. The appropriate CD4+-T-cell clone could be administered to patients with the corresponding MHC II allele. In the instance of donor lymphomas arising in recipients of allogeneic T-cell-depleted bone marrow or stem cell transplants, the CD4+-T-cell clone would be matched to the donor. In the case of posttransplant LPD (PTLD) arising following solid organ transplantation, the CD4+-T-cell clone would be matched to the recipient (23, 47). This strategy might be more efficient than the current, time-intensive approach of adoptive immunoprophylaxis and therapy of PTLD, which involves raising LCLs and subsequently polyclonal EBV-reactive T-cell lines for each individual.

When CD4+-T-cell clones directed against EBNA1 are used clinically, it will be essential to determine whether the bystander cytotoxicity that these clones exhibit in vitro will have beneficial or harmful effects. As shown in Fig. 7, clones which had been activated by EBNA1-expressing MHC II-matched targets exerted cytotoxic effects in vitro against targets that were in direct contact with the T cells but were not MHC II matched. Clones would be activated in vivo by EBV-positive, EBNA1-expressing cells. Bystander activity might augment control over other cells in the immediate area, which might contribute to lymphoma tumor burden. For example, B cells within the lymphoma population which present EBNA1 antigen inefficiently but are stimulated to express Fas upon EBV infection would be subject to bystander killing even if those cells alone would not have stimulated T-cell activity. On the other hand, bystander reactions may be a potential source of unwanted toxicity by the clones, particularly if the T cells remain activated even after they have migrated away from the EBV-infected tumor cells which provided the initial stimulus.

The approach of using well-characterized T-cell clones in immunotherapy and immunoprophylaxis need not be limited to CD4+-T-cell clones directed against EBNA1. T cells reactive towards many viral antigens are primed during primary infection and likely help prevent the development of EBV-associated malignancies in healthy carriers. EBNA1-reactive clones might be given in combination with CD4+-T-cell clones directed against EBNA2, LMP2a, or lytic cycle antigens, such as BHRF1 (60, 85, 88, 92). These could be mixed with cytotoxic CD8+-T-cell clones specific for the immunodominant EBNA3A, EBNA3C, or LMP2 proteins. Such comprehensive immunotherapy would not be limited to LPDs but might be applied to other EBV malignancies, such as Hodgkin's disease and BL (61, 73).

Since EBNA1 is the only viral protein consistently expressed in all forms of viral infection and is not well recognized by CD8+ T cells, the potential contribution of EBNA1-reactive CD4+-T-cell clones to adoptive immunotherapy regimens against PTLD and many EBV-associated tumors merits further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Cliona Rooney for a critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Peter Doherty for suggesting that we investigate bystander phenomena. We thank Reva Goggins and Lisa Geiselhart for assistance with HLA haplotyping of cell lines and donors.

This work was supported by grants CA12055 and CA16038 from the National Institutes of Health (G.M.). S.N. was supported by Medical Scientist Training Program grant GM07205, the John F. Enders Research Fund of Yale University School of Medicine, and the Anna Fuller Pediatric Oncology Fund. C.M. was supported by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Foundation and the Speaker's Fund for Public Health Research of the New York Academy of Medicine.

Footnotes

We dedicate the manuscript to Charles A. Janeway, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman, J. D., P. A. Moss, P. J. Goulder, D. H. Barouch, M. G. McHeyzer-Williams, J. I. Bell, A. J. McMichael, and M. M. Davis. 1996. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 274:94-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ando, K., K. Hiroishi, T. Kaneko, T. Moriyama, Y. Muto, N. Kayagaki, H. Yagita, K. Okumura, and M. Imawari. 1997. Perforin, Fas/Fas ligand, and TNF-alpha pathways as specific and bystander killing mechanisms of hepatitis C virus-specific human CTL. J. Immunol. 158:5283-5291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azim, T., and D. H. Crawford. 1988. Lymphocytes activated by the Epstein-Barr virus to produce immunoglobulin do not express CD23 or become immortalized. Int. J. Cancer 42:23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babcock, G. J., L. L. Decker, R. B. Freeman, and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 1999. Epstein-Barr virus-infected resting memory B cells, not proliferating lymphoblasts, accumulate in the peripheral blood of immunosuppressed patients. J. Exp. Med. 190:567-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babcock, G. J., D. Hochberg, and A. D. Thorley-Lawson. 2000. The expression pattern of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes in vivo is dependent upon the differentiation stage of the infected B cell. Immunity 13:497-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnstable, C. J., W. F. Bodmer, G. Brown, G. Galfre, C. Milstein, A. F. Williams, and A. Ziegler. 1978. Production of monoclonal antibodies to group A erythrocytes, HLA and other human cell surface antigens—new tools for genetic analysis. Cell 14:9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bickham, K., C. Münz, M. L. Tsang, M. Larsson, J. F. Fonteneau, N. Bhardwaj, and R. Steinman. 2001. EBNA1-specific CD4+ T cells in healthy carriers of Epstein-Barr virus are primarily Th1 in function. J. Clin. Investig. 107:121-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blake, N., T. Haigh, G. Shaka'a, D. Croom-Carter, and A. Rickinson. 2000. The importance of exogenous antigen in priming the human CD8+ T cell response: lessons from the EBV nuclear antigen EBNA1. J. Immunol. 165:7078-7087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blake, N., S. Lee, I. Redchenko, W. Thomas, N. Steven, A. Leese, P. Steigerwald-Mullen, M. G. Kurilla, L. Frappier, and A. Rickinson. 1997. Human CD8+ T cell responses to EBV EBNA1: HLA class I presentation of the (Gly-Ala)-containing protein requires exogenous processing. Immunity 7:791-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bornkamm, G. W., H. Delius, U. Zimber, J. Hudewentz, and M. A. Epstein. 1980. Comparison of Epstein-Barr virus strains of different origin by analysis of the viral DNAs. J. Virol. 35:603-618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calender, A., M. Billaud, J. P. Aubry, J. Banchereau, M. Vuillaume, and G. M. Lenoir. 1987. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) induces expression of B-cell activation markers on in vitro infection of EBV-negative B-lymphoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:8060-8064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callan, M. F., L. Tan, N. Annels, G. S. Ogg, J. D. Wilson, C. A. O'Callaghan, N. Steven, A. J. McMichael, and A. B. Rickinson. 1998. Direct visualization of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during the primary immune response to Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 187:1395-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumont, C., A. Durrbach, N. Bidere, M. Rouleau, G. Kroemer, G. Bernard, F. Hirsch, B. Charpentier, S. A. Susin, and A. Senik. 2000. Caspase-independent commitment phase to apoptosis in activated blood T lymphocytes: reversibility at low apoptotic insult. Blood 96:1030-1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finn, L., J. Reyes, J. Bueno, and E. Yunis. 1998. Epstein-Barr virus infections in children after transplantation of the small intestine. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 22:299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer, D. K., M. F. Robert, D. Shedd, W. P. Summers, J. E. Robinson, J. Wolak, J. E. Stefano, and G. Miller. 1984. Identification of Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen polypeptide in mouse and monkey cells after gene transfer with a cloned 2.9-kilobase-pair subfragment of the genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:43-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frappier, L., and M. O'Donnell. 1991. Overproduction, purification, and characterization of EBNA1, the origin binding protein of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Biol. Chem. 266:7819-7826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu, Z., and M. J. Cannon. 2000. Functional analysis of the CD4+ T-cell response to Epstein-Barr virus: T-cell-mediated activation of resting B cells and induction of viral BZLF1 expression. J. Virol. 74:6675-6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furukawa, T. 1975. Epstein-Barr virus: comparison of different strains for their biological activities in vitro. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 10:543-553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldsmith, K., L. Bendell, and L. Frappier. 1993. Identification of EBNA1 amino acid sequences required for the interaction of the functional elements of the Epstein-Barr virus latent origin of DNA replication. J. Virol. 67:3418-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorga, J. C., P. J. Knudsen, J. A. Foran, J. L. Strominger, and S. J. Burakoff. 1986. Immunochemically purified DR antigens in liposomes stimulate xenogeneic cytolytic T cells in secondary in vitro cultures. Cell. Immunol. 103:160-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green, M., M. G. Michaels, S. A. Webber, D. Rowe, and J. Reyes. 1999. The management of Epstein-Barr virus associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders in pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients. Pediatr. Transplant. 3:271-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagihara, M., T. Tsuchiya, Y. Ueda, A. Masui, B. Gansuvd, B. Munkhbat, H. Inoue, O. Hyodo, K. Ando, S. Kato, and T. Hotta. 2001. Successful in vitro generation of Epstein-Barr virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes from severe chronic active EBV patients. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berlin) 189:137-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haque, T., C. Taylor, G. M. Wilkie, P. Murad, P. L. Amlot, S. Beath, P. J. McKiernan, and D. H. Crawford. 2001. Complete regression of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease using partially HLA-matched Epstein Barr virus-specific cytotoxic T cells. Transplantation 72:1399-1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.HayGlass, K. T., M. Wang, R. S. Gieni, C. Ellison, and J. Gartner. 1996. In vivo direction of CD4 T cells to Th1 and Th2-like patterns of cytokine synthesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 409:309-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill, A. B., S. P. Lee, J. S. Haurum, N. Murray, Q. Y. Yao, M. Rowe, N. Signoret, A. B. Rickinson, and A. J. McMichael. 1995. Class I major histocompatibility complex-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed B lymphoblastoid cell lines against which they were raised. J. Exp. Med. 181:2221-2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffmann, T., C. Russell, and L. Vindelov. 2002. Generation of EBV-specific CTLs suitable for adoptive immunotherapy of EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disease following allogeneic transplantation. APMIS 110:148-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honda, S., T. Takasaki, K. Okuno, M. Yasutomi, and I. Kurane. 1998. Establishment and characterization of Epstein-Barr virus-specific human CD4+ T lymphocyte clones. Acta Virol. 42:307-313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoshino, Y., T. Morishima, H. Kimura, K. Nishikawa, T. Tsurumi, and K. Kuzushima. 1999. Antigen-driven expansion and contraction of CD8+-activated T cells in primary EBV infection. J. Immunol. 163:5735-5740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurley, E. A., and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 1988. B cell activation and the establishment of Epstein-Barr virus latency. J. Exp. Med. 168:2059-2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inman, G. J., U. K. Binne, G. A. Parker, P. J. Farrell, and M. J. Allday. 2001. Activators of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic program concomitantly induce apoptosis, but lytic gene expression protects from cell death. J. Virol. 75:2400-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaraquemada, D., M. Marti, and E. O. Long. 1990. An endogenous processing pathway in vaccinia virus-infected cells for presentation of cytoplasmic antigens to class II-restricted T cells. J. Exp. Med. 172:947-954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karp, J. E., and S. Broder. 1991. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Cancer Res. 51:4743-4756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kataoka, T., K. Togashi, H. Takayama, K. Takaku, and K. Nagai. 1997. Inactivation and proteolytic degradation of perforin within lytic granules upon neutralization of acidic pH. Immunology 91:493-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsuki, T., and Y. Hinuma. 1975. Characteristics of cell lines derived from human leukocytes transformed by different strains of Epstein-Barr virus. Int. J. Cancer 15:203-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kayagaki, N., N. Yamaguchi, M. Nakayama, A. Kawasaki, H. Akiba, K. Okumura, and H. Yagita. 1999. Involvement of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in human CD4+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J. Immunol. 162:2639-2647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khanna, R., S. R. Burrows, M. G. Kurilla, C. A. Jacob, I. S. Misko, T. B. Sculley, E. Kieff, and D. J. Moss. 1992. Localization of Epstein-Barr virus cytotoxic T cell epitopes using recombinant vaccinia: implications for vaccine development. J. Exp. Med. 176:169-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khanna, R., S. R. Burrows, P. M. Steigerwald-Mullen, D. J. Moss, M. G. Kurilla, and L. Cooper. 1997. Targeting Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) through the class II pathway restores immune recognition by EBNA1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes: evidence for HLA-DM-independent processing. Int. Immunol. 9:1537-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khanna, R., S. R. Burrows, P. M. Steigerwald-Mullen, S. A. Thomson, M. G. Kurilla, and D. J. Moss. 1995. Isolation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes from healthy seropositive individuals specific for peptide epitopes from Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1: implications for viral persistence and tumor surveillance. Virology 214:633-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klein, G., J. Zeuthen, P. Terasaki, R. Billing, R. Honig, M. Jondal, A. Westman, and G. Clements. 1976. Inducibility of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) cycle and surface marker properties of EBV-negative lymphoma lines and their in vitro EBV-converted sublines. Int. J. Cancer 18:639-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koehne, G., K. M. Smith, T. L. Ferguson, R. Y. Williams, G. Heller, E. G. Pamer, B. Dupont, and R. J. O'Reilly. 2002. Quantitation, selection, and functional characterization of Epstein-Barr virus-specific and alloreactive T cells detected by intracellular interferon-gamma production and growth of cytotoxic precursors. Blood 99:1730-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Konttinen, Y. T., H. G. Bluestein, and N. J. Zvaifler. 1985. Regulation of the growth of Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells. I. Growth regression by E rosetting cells from VCA-positive donors is a combined effect of autologous mixed leukocyte reaction and activation of T8+ memory cells. J. Immunol. 134:2287-2293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lampson, L. A., and R. Levy. 1980. Two populations of Ia-like molecules on a human B cell line. J. Immunol. 125:293-299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leen, A., P. Meij, I. Redchenko, J. Middeldorp, E. Bloemena, A. Rickinson, and N. Blake. 2001. Differential immunogenicity of Epstein-Barr virus latent-cycle proteins for human CD4+ T-helper 1 responses. J. Virol. 75:8649-8659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levitskaya, J., M. Coram, V. Levitsky, S. Imreh, P. M. Steigerwald-Mullen, G. Klein, M. G. Kurilla, and M. G. Masucci. 1995. Inhibition of antigen processing by the internal repeat region of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1. Nature 375:685-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levitskaya, J., A. Sharipo, A. Leonchiks, A. Ciechanover, and M. G. Masucci. 1997. Inhibition of ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent protein degradation by the Gly-Ala repeat domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12616-12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, J. H., D. Rosen, D. Ronen, C. K. Behrens, P. H. Krammer, W. R. Clark, and G. Berke. 1998. The regulation of CD95 ligand expression and function in CTL. J. Immunol. 161:3943-3949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]