Abstract

n-(n-Nonyl)-deoxygalactonojirimycin (n,n-DGJ), an alkylated imino sugar, reduces the amount of HBV DNA produced within the stably transfected HBV-producing HepG2.2.15 line in culture and is under consideration for development as a human therapeutic. n,n-DGJ does not appear to inhibit HBV DNA polymerase activity or envelop antigen production (A. Mehta, S. Carrouee, B. Conyers, R. Jordan, T. Butters, R. A. Dwek, and T. M. Block, Hepatology 33:1488-1495, 2001), and the mechanism of antiviral action is unknown. In this study, the step in the virus life cycle affected by n,n-DGJ was explored. Using Northern analysis and immunoprecipitation with anti-HBc antibody, we found that, under conditions in which cell viability was not affected but viral DNA production was substantially reduced, neither the amount of HBV transcription products nor the core polypeptide was detectably reduced. However, the pregenomic RNA, endogenous polymerase activity, and core polypeptide sedimenting in sucrose gradients with a density consistent with that of assembled nucleocapsids were significantly less in the HepG2.2.15 cells incubated with n,n-DGJ. These data suggest that n,n-DGJ either prevents the maturation of HBV nucleocapsids or destabilizes the formed nucleocapsids. Although the cellular and viral mediators of this inhibition are not known, depletion of nucleocapsid has been attributed to some other compounds as well as interferon's mechanism of anti-HBV action. The similarities and differences between this alkylated imino sugar and these other mediators are discussed.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major human pathogen responsible for acute and chronic liver disease. An estimated 400 million people worldwide and more than 1.25 million people in United States are chronically infected with this virus (9). Infected individuals have significant lifetime risk of developing liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, which accounts for more than 1 million deaths per year worldwide (9). Therefore, despite the availability and use of an effective vaccine, HBV infection remains an important public health problem, and therapeutics that complement the three U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs (alpha interferon, lamivudine, and adefovir) are important to develop. n-(n-Nonyl)-deoxygalactonojirimycin (n,n-DGJ), an alkylated imino sugar with a galactose head and a nine-carbon side chain (tail) (Fig. 1), was shown to cause a reduction of the intracellular replicative forms of HBV DNA in HepG2.2.15 cells in a dose-dependent manner (25). Unlike the antiviral alkylated imino sugars with glucose head groups, such as n-(n-nonyl)-deoxynojirimycin (3), n,n-DGJ does not inhibit glycan processing. This rules out the inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum glucosidases as an antiviral mechanism of n,n-DGJ, which has been proved to be essential to n-(n-nonyl)-deoxynojirimycin's antiviral action (3-6, 25). Since n,n-DGJ inhibits neither HBV transcription, envelope polypeptide production, nor endogenous polymerase activity and yet reduces the amount of viral DNA, it seemed possible that the nucleocapsid maturation or stabilization was affected.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of n,n-DGJ. n,n-DGJ is an alkylated imino sugar, with a galactose head group, modified by a nine-carbon side chain alkyl group from the ring nitrogen. Hydroxals are shown to emphasize stereo relationships.

HBV replication begins with the encapsidation of the viral pregenomic RNA and polymerase by envelopment of viral core proteins to form immature nucleocapsid particles or assembled core particles (14, 15, 20, 26). Negative strands of viral DNA are synthesized through reverse transcription of the pregenomic RNA, which is degraded during the process. The negative-strand DNA is then used as a template for positive-strand synthesis (27, 29). Core protein phosphorylation is also believed to play a role in HBV replication (10, 17, 19).

To determine whether the reduction in HBV replication mediated by n,n-DGJ is due to depletion of HBV nucleocapsid, sucrose gradient centrifugation was used to separate assembled and unassembled forms of core proteins derived from HepG2.2.15 cells. The results show that, although n,n-DGJ does not detectably influence steady-state levels of either viral transcripts, core, or envelope polypeptide, the amount of viral gene product sedimenting through sucrose gradients as intact nucleocapsid was considerably reduced in the treated cells. These data suggest that n,n-DGJ influences either nucleocapsid formation or accumulation but not production or accumulation of core or envelope protein. Since HBV DNA replication is dependent upon nucleocapsid assembly, interference with this process can, in itself, explain the impact of n,n-DGJ upon viral DNA levels. How an alkylated imino sugar such as n,n-DGJ can trigger the depletion of HBV nucleocapsid is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and cell lines.

n,n-DGJ was supplied by Synergy, Inc. (Somerset, N.J). The HepG2.2.15 cell line was kindly provided by George Acs (Mt. Sinai Medical College, New York, N.Y.) and has been maintained in our laboratory for more than 8 years. HepG2 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md. Both cell lines were maintained in a RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) made in 10% fetal bovine serum. A total of 200 μg of G418/ml was included in the medium for HepG2.2.15 cells. For drug treatment, HepG2.2.15 cells were seeded in T25 flasks and grown until confluence. Then, 20 μg of n,n-DGJ/ml was added in culture medium and maintained for 6 days. The medium was changed every 2 days.

Southern and Northern blot detection of HBV DNA in HepG2.2.15 cells.

HepG2.2.15 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium and treated with 20 μg of n,n-DGJ/ml for 6 days. Cells were lysed with 0.8 ml of 0.01 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-0.05 M NaCl-0.5% NP-40-1 mM EDTA at room temperature for 10 min as described previously (24). The nuclei and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. Next, 0.5 mg of proteinase K/ml was added to the supernatant, followed by incubation at 37°C overnight. By using detergent NP-40 and overnight protease K treatment, we found that the digestion was more complete. HBV DNA was extracted by two times phenol-chloroform isolation and precipitated by adding 2 volumes of 100% ethanol at −20°C overnight. Pellets were dissolved in 0.01 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). Then, 10-μg samples (we determined the absorbance at an optical density of 260 nm) were resolved by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA was transferred to nylon membrane for Southern blot analysis. “Southern” blotting was performed essentially as described by Lu et al. (24). The probe was made from PCR amplification of purified HBV DNA. Briefly, HBV DNA that was used as a template for PCR was purified from agarose gels after electrophoresis. PCR was performed as described before except that 20 μCi of [32P]dCTP was used in place of the nonradioactive dCTP (21). 32P-labeled HBV DNA fragment and the 561-nucleotide product were purified by using a ProbeQuant G50 microcolumn (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.). The membranes were hybridized with HBV probe (>107 cpm/ml) at 65°C, overnight. The images were acquired by using a phosphorimager. For Northern blot analysis, total RNA was isolated from n,n-DGJ-treated and untreated HepG2.215 cells by using the StrataPrep Total RNA Miniprep kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). A total of 20 μg of RNA was resolved in 1% nondenatured gel and then transferred to nylon membrane according to the instructions of Northern Max kit (Ambion, Austin, Tex.). The membrane was hybridized with 32P-labeled HBV DNA fragment described above. For the second hybridization of actin, the first probe was removed from the membrane by a wash at a high temperature in 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) solution for 10 min and then hybridized with 32P-labeled probe for actin.

Cell labeling and sucrose gradient centrifugation to determine the density of core particles.

Confluent monolayers of HepG2.2.15 cells that were left untreated or treated with n,n-DGJ were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 3 ml of methionine-lacking RPMI 1640 medium for 30 min. Cells were labeled with 100 μCi of [35S] methionine (Amersham)/ml overnight in the medium with 20 μg of n,n-DGJ/ml. After three washes with PBS, the cells were released by trypsin digestion and transferred to 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. Cells were precipitated by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 5 min, and the pellets were then lysed with 0.8 ml of 0.05 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-0.15 M NaCl-0.005 M MgCl2-0.2% NP-40 at room temperature for 30 min. The nuclei and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. The lysate was collected and the radioactivity was determined by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation. Briefly, 2 μl of lysate was absorbed by Whatman 3MM paper (1 cm in diameter; Whatman, Maidstone, England) and then precipitated by using 10% TCA. After three 5-min washes with 10% TCA, the radioactivity was counted by using a liquid scintillation counter. For total core protein analysis, 100 μl of cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with 30 μl of protein G-beads (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) at 4°C overnight, which was preabsorbed with monoclonal anti-HBc antibody (1 μg/ml; Virogen, Boston, Mass.). After four washes with PBS-0.05% Tween 20, the core proteins were released from the beads by heating them at 95°C for 10 min in 20 μl of sample buffer and then resolved by SDS-12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). In order to decrease the background, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), and images were analyzed by using a phosphorimager. For analysis of assembled and unassembled core protein, ca. 1.8 × 109 counts of lysate (0.6 ml) per min from drug-treated or untreated cells was loaded on the top of a sucrose gradient (0.7 ml of 60% [wt/wt] sucrose, 0.7 ml of 50% sucrose, 0.7 ml of 40% sucrose, 0.7 ml of 30% sucrose, 0.7 ml of 20% sucrose, and 0.7 ml of 10% sucrose in PBS) in an SW55 rotor (Beckman), followed by centrifugation for 3 h at 55,000 rpm at 4°C. Eight fractions (0.65 ml) were taken from the top and stored at −20°C. The core protein in each fraction was determined by immunoprecipitation with anti-HBc. The sucrose was removed from samples by dialysis. Briefly, a 150-μl sample from each fraction was laid on a dialysis dish paper (4-cm diameter; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) and dialyzed against PBS for 1.5 h. The samples were finally diluted to 1 ml with PBS with 2% bovine serum albumin. The samples were then incubated with protein G beads and resolved by SDS-PAGE as described above. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad), and the images were analyzed by using a phosphorimager.

Analysis of encapsidated RNA.

A total of 106 HepG2.2.15 cells either untreated or treated with n,n-DGJ were lysed and fractionated through sucrose gradients as described above. Core particles in each fraction were immunoprecipitated by using anti-HBc as described above. After a washing step, the RNA was released from beads by incubation with 100 μl of RNA isolation lysis buffer containing 1 μl of β-mercaptoethanol (from the StrataPrep Total RNA Miniprep kit) for 5 min at room temperature. Beads were removed by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 3 min. Then, 1 μg of total RNA from HepG2 cells was added to the supernatant. RNA was precipitated by 2.5 volumes of 100% ethanol at −20°C overnight. The pellets were dissolved in 20 μl of formaldehyde load dye buffer and resolved by using 1% agarose denatured gel for the Northern blot as described by the manufacturer (Ambion). RNA was then transferred to a nylon membrane and hybridized with 32P-labeled HBV-specific probe made by PCR amplification of the HBV DNA described above. The membranes were hybridized with HBV probe (>107 cpm/ml) at 42°C overnight by using the Northern blot kit from Ambion. The images were quantified with a phosphorimager.

Analysis of encapsidated DNA polymerase by EPR.

Cell lysates were fractionated and immunoprecipitated by anti-HBc as described above. The beads were washed with PBS-Tween 20, and an endogenous polymerase reaction (EPR) was performed as described by Bruss and coworkers (7, 18). Briefly, after the removal of all liquid with a thin glass capillary, 50 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.15 mM NH4Cl, 20 mM EDTA, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.1% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5% (vol/vol) NP-40, 0.4 mM dATP, 0.4 mM dGTP, 0.4 mM dTTP, and 10 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP was added, followed by incubation at 37°C overnight. The samples were then incubated with 50 μl of proteinase K (at 0.5 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer [pH 7.5] with 1% SDS and 10 mM EDTA) at 37°C for 30 min. Next, 40 μg of tRNA per sample was added, and the labeled viral genome was extracted once with 0.1 ml of phenol-chloroform (1:1). Then, the DNA was separated from unincorporated radioactive dCTP by precipitation with 25 μl of 10 M ammonium acetate and 250 μl of ethanol, incubation for 15 min at room temperature, and spinning for 15 min in a desktop microcentrifuge. The pellet was dissolved in 0.1 ml of Tris-EDTA buffer, and the DNA was precipitated again as described above. The pellets were dissolved in 15 μl of sample buffer and applied to a 1% agarose gel. Finally, DNA was transferred to the nylon membrane and subjected to radioautography by using a phosphorimager.

Core protein phosphorylation assay.

Confluent HepG2.2.15 cells in T25 flasks were either treated or not treated with n,n-DGJ for 6 days as described above. Cells were washed with PBS two times and then incubated with 3 ml of phosphoric acid-free Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Fisher, Pittsburgh, Pa.) with 20 μg of n,n-DGJ/ml for 3 h. Cells were then labeled with 1.5 ml of medium containing 32P (0.5 mCi/ml; Amersham) and 20 μg of n,n-DGJ/ml overnight. After three washes with PBS, cells were lysed with 1 ml of lysis buffer (0.05 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.15 M NaCl, 0.005 M MgCl2, 0.2% NP-40) at room temperature for 30 min. The nuclei and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. Core protein was immunoprecipitated with anti-HBc, followed by SDS-PAGE as described above. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane, and images were analyzed by using a phosphorimager.

RESULTS

Incubation with n,n-DGJ reduces the amount of HBV DNA replicative forms but not RNA levels in HepG2.2.15 cells.

The treatment of HepG2.2.15 cells with n,n-DGJ reduces the replication of HBV, as reported by Mehta et al. (25). This was confirmed, here, by Southern blot analysis of cytoplasmic HBV DNA after incubation of cells with 20 μg of n,n-DGJ/ml for 6 days (see Materials and Methods). Briefly, HepG2.2.15 cells were incubated with or without n,n-DGJ for 6 days. Cytoplasmic DNA was isolated, resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, and hybridized to radiolabeled HBV-specific probes.

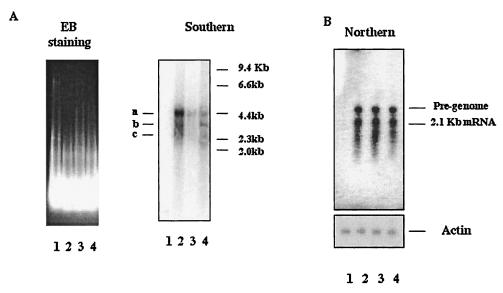

As shown in Fig. 2A, HBV-specific bands can only be detected in the sample from HepG2.2.15 cells and not in the sample from HepG2 cells (Fig. 2A, Southern blot). Based upon the molecular mass and pattern of the three size species of HBV-specific DNA and by comparison to the results of Sells et al. (30), we conclude that these are the relaxed circular (RC), double-stranded linear (DL), and probably single-stranded (SS) forms of HBV intracellular DNA. Since we have not confirmed these identities, we designated these forms “a,” “b,” and “c,” respectively, here. Phosphorimager quantification of the bands corresponding to the putative RC form of HBV DNA reveals that the amount of HBV DNA detected in n,n-DGJ-treated cells was reduced by ca. 80% compared to untreated controls (Fig. 2A, Southern blot, lanes 2 and 4). The reduction in viral DNA replicative forms was not due to an impact upon loading or cell viability. Figure 2A shows that a similar amount of cellular DNA were loaded into the gel, as confirmed by ethidium bromide staining. An absence of detectable impact of the drug upon cell viability was demonstrated by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide analysis. Briefly, after 6 days of n,n-DGJ treatment, there was no significant difference in viability between treated and untreated cells (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

n,n-DGJ reduces the amount of replicative forms of HBV DNA but not HBV RNA in HepG2.2.15 cells. HBV DNA or total RNA was isolated from the cytoplasm of HepG2.2.15 cells that had been left untreated or treated with n,n-DGJ (20 μg/ml) for 6 days. To perform Southern or Northern blots, a 10-μg sample or 20 μg of total RNA was resolved in a 1% agarose gel and then transferred to the nylon membrane. The membrane was hybridized with HBV-specific probe labeled with [32P]dCTP. HepG2 cells and HepG2.2.15 cells treated with 3TC were used for comparison. (A) Results of Southern blot (right) and ethidium bromide staining of the agarose gel of the Southern blot (left) show the equal loading of the samples. The three HBV replication intermediates forms generated by the HepG2.2.15 cells (a, b, and c) and size markers are indicated in kilobases. (B) Results of a Northern blot. The same membrane was first hybridized with [32P]dCTP-labeled HBV-specific probe (upper panel) and then rehybridized with an actin probe (lower panel) after removal of the previous probe by washing in 0.5% SDS-0.1× SSC stripe buffer. Lanes: 1, HepG2; 2, untreated; 3, 3TC; 4, n,n-DGJ+.

The reduction in viral DNA replicative forms in n,n-DGJ-treated HepG2.2.15 cells (as shown in Fig. 2A) was also not due to an impact upon the amount of accumulated HBV RNA. This finding was supported by Northern blot analysis. RNA prepared from HepG2.215 cells either left untreated or incubated with n,n-DGJ or 3TC was resolved through agarose gels and hybridized with probes specific for HBV sequences. As expected, HepG2 cells, which do not have HBV sequences, were devoid of HBV-specific RNA. However, HBV-specific RNA derived from HepG2.2.15 cells resolves into two general families of ∼2.1 kb (subgenomic) and 3.2 kb (presumably includes the pregenomic species). The abundance of HBV-specific RNA was similar in all samples derived from HepG2.2.15 cells, regardless of drug treatment (Fig. 2B). Thus, neither 3TC nor n,n-DGJ had any detectable impact upon HBV RNA levels after 6 days of treatment. Figure 2B also shows that the level of actin RNA in each sample was nearly equal in n,n-DGJ-treated and untreated cells. Thus, the reduction of viral DNA was selective and was not due to reduction in viral RNA or a loss in viability.

n,n-DGJ treatment reduces the amount of core polypeptide that sediments to high density in sucrose gradients: evidence that nucleocapsid formation or accumulation is reduced.

Since, compared to untreated HepG2.2.15 cells, n,n-DGJ-incubated cells had considerably fewer replicative forms of HBV DNA and yet previous studies showed the level of viral RNA, polypeptide, and endogenous polymerase activity was apparently unchanged (25), our attention turned to the possibility that either core polypeptide or HBV nucleocapsid had been affected. HBV nucleocapsids, containing polymerase and nucleic acid, can be resolved from unassembled core protein by sedimentation through a sucrose gradient by ultracentrifugation (10). Nucleocapsids sediment to a high density of the sucrose gradient, separating from unassembled core protein that remains at a low density (10). Therefore, to determine whether the abundance or nature of nucleocapsids was altered in cells incubated with n,n-DGJ, HepG2.2.15 cells were incubated either with or without compound for 6 days as described above. For nucleocapsid analysis, 106 cells were labeled with [35S]methionine.

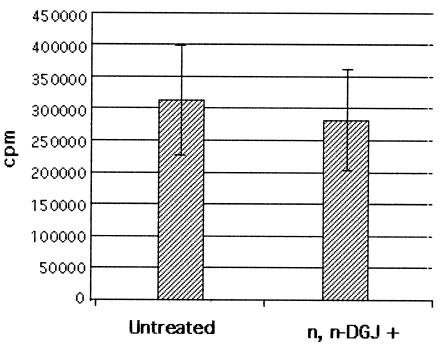

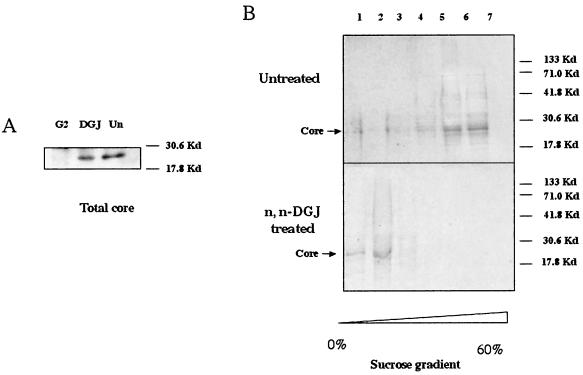

Treated and untreated cells accumulated similar amounts of total radioactivity, a finding consistent with the observation that the drug was not toxic at the concentrations used (Fig. 3). This result was confirmed by the detection of total core protein in n,n-DGJ-treated and untreated cells. We incubated 100-μl cell lysates, prepared as described in Materials and Methods, with protein G beads preabsorbed by anti-core antibody, and the core protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE. As expected, core protein was detected in the sample from HepG2.2.15 cells but not in the sample from HepG2 cells (Fig. 4A). The same result was observed by staining these bands with anti-core monoclonal antibody after the proteins were transferred to membrane (data not shown). However, Fig. 4A shows that there was no significant difference in the amount of total core protein recovered from treated and untreated samples. This result also suggests that n,n-DGJ did not significantly affect the synthesis of core protein. Thus, the possibility that n,n-DGJ had an impact upon nucleocapsids was explored.

FIG. 3.

Metabolic labeling of HepG2.2.15 cells used in sucrose gradient fractionations. HepG2.2.15 cells left untreated or treated with n,n-DGJ for 6 days were labeled with [35S]methionine overnight as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were lysed, and nuclei were removed. Then, 2 μl of total protein in the samples was precipitated by 10% TCA. After three washes with 10% TCA, the radioactivity was counted.

FIG. 4.

n,n-DGJ prevents the assembly of HBV nucleocapsids. HepG2.2.15 cells left untreated or treated with n,n-DGJ were labeled with [35S]methionine as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Total core protein in n,n-DGJ-treated and untreated cells. Cell lysates (100 μl) were incubated with protein G beads preabsorbed with a monoclonal antibody specific for HBV core at 4°C overnight. The core protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE. Bands were analyzed by using a phosphorimager (see Materials and Methods). (B) The same amount of labeled protein in the cell lysate (with counts per minute determined as shown in Fig. 3) was loaded on the 10 to 60% sucrose gradient and centrifuged at 55,000 rpm with a Beckman SW55 rotor for 3 h at 4°C, followed by fractionation after sucrose gradient centrifugation. Core protein and associated materials were immunoprecipitated and then resolved by SDS-PAGE as described above. Bands were analyzed by using a phosphorimager. The assembled and unassembled HBV core particles were resolved at a high sucrose density (fractions 5 and 6) and a low sucrose density (fractions 1 to 3), respectively. The molecular weight markers and core protein are indicated. The sucrose density of the fractions is represented by the scale at the bottom.

Cell lysates, prepared from the samples described in Fig. 4A, were layered on the top of 10 to 60% (wt/wt) sucrose gradients. Equal total amounts of radioactivity were loaded from all samples to ensure that equal amounts of cell lysate were analyzed (see Materials and Methods). The lysates were sedimented at 55,000 rpm for 3 h and then fractionated. Core proteins were immunoprecipitated from each fraction with an anti-core monoclonal antibody and resolved by SDS-PAGE. As expected(10), the profile from untreated HepG2.2.15 cells shows that most of core polypeptides resolved into the regions of the high density of the gradient (Fig. 4B, fractions 5 and 6). The amount of detectable core in the low-density fractions, where disaggregated or unassembled core would be expected, was very small. The situation with core derived from n,n-DGJ-treated cells is strikingly different, with most detectable core sedimenting in the low-density fractions (Fig. 4B, fractions 1 and 2, n,n-DGJ treated). In contrast, there was very little core peptide that sedimented in the high-density fraction, which could only be seen after a long exposure (data not shown). These results are consistent with the possibility that n,n-DGJ treatment of HepG2.2.15 cells has an impact upon HBV nucleocapsid morphogenesis or stability.

Amount of HBV core-associated viral RNA in HepG2.2.15 cells as a function of n,n-DGJ treatment.

In order to further characterize and confirm that the core particles sedimenting to the high-density fraction of the sucrose gradient are HBV nucleocapsids, the presence of viral RNA in the complexes was determined. HepG2.2.15 cells were incubated with or without n,n-DGJ for 6 days and prepared for either analysis of “total RNA” or for analysis of nucleocapsid containing RNA after fractionation through sucrose gradients (as described in Materials and Methods). As observed above, the total HBV RNA products, full-length HBV genomic RNA (3.2 kb) and subgenomic RNA (2.1 kb) forms in HepG2.2.15 cells, did not change after 6 days of incubation with n,n-DGJ, as determined by Northern analysis (Fig. 5A, total RNA). These findings suggest that the steady-state abundance of these transcripts was not affected by n,n-DGJ treatment. For HBV nucleocapsid analysis, the viral RNA associated with core protein was examined by using material from the fractions from the sucrose gradient described for Fig. 4B. Briefly, cell lysates were resolved by sucrose gradient centrifugation, and each fraction was immunoprecipitated with core antibody. The immunoprecipitated RNA was further analyzed by Northern blot, and the results are shown in Fig. 5A. Consistent with the findings of other researchers, the HBV RNA associated with nascent nucleocapsids appears as a smearing signal, starting from the position of the pregenome RNA. This occurs apparently, in part, as a consequence of degradation of RNA that takes place immediately after encapsidation (1, 2, 13). Moreover, for nucleocapsids containing HBV DNA, which is not degraded by DNase in preparation, the smear may even cause the HBV signal to run more slowly (to an apparently higher-molecular-weight position) than the full-length molecular form (1, 2, 13). As shown in Fig. 5A, HBV-specific RNA that migrates with and ahead of the full length is clearly coprecipitated with the core from the high-density gradient fractions associated with assembled nucleocapsids (Fig. 5A, fractions 5 and 6). That RNA comigrating with full-length pregenomes and coprecipitating with core protein after immunoprecipitation can only be detected in the fractions in the high-density region of the sucrose gradient and not in the fractions at the low density (Fig. 5A, fractions 5 and 6 and 1 to 3) is in agreement with the notion that core polypeptides resolving to the high-density region of the sucrose gradient are associated with HBV RNA containing nucleocapsid. The relative absence of HBV RNA in immunoprecipitates of core sedimenting at the low-density region of the sucrose gradient (see Fig. 4B) supports the hypothesis that these core polypeptides are not associated with intact nucleocapsids and are most likely not assembled.

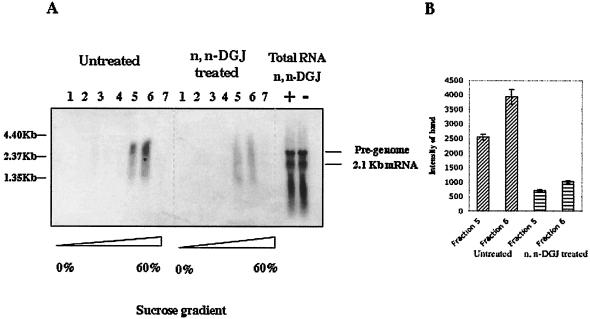

FIG. 5.

Northern blot detects the HBV RNA in the assembled core particles. (A) HepG2.2.15 cells treated or not treated with n,n-DGJ were lysed and then centrifuged through a sucrose gradient as described in Fig. 4 legend. Aliquots of fractions from the sucrose gradient were incubated with protein G beads preabsorbed with anti-core antibody at 4°C overnight. After several washes, the beads were treated with cell lysis buffer at room temperature for 5 min. HBV RNA and replication intermediates in the nucleocapsids were coprecipitated with 1 mg of RNA isolated from HepG2 cells by using ethanol, resolved in 1% denatured gel, and transferred to nylon membrane for Northern blotting. Membranes were hybridized with 32P-labeled HBV probe. Images were acquired by using a phosphorimager. The sucrose densities of the fractions are indicated at the bottom of the panel. For total RNA, HepG2.2.15 cells were lysed, and RNA was isolated and purified with the RNA isolation kit (Strategene). Genomic DNA was degraded by DNase. Then, 20 mg of RNA was resolved in 1% denatured gel and hybridized with 32P-labeled HBV probe. See Materials and Methods for details. (B) Phosphorimager quantitative analysis of HBV RNA and replicative intermediates in the nucleocapsid at high sucrose density fractions (fractions 5 and 6) in n,n-DGJ-treated and untreated HepG2.2.15 cells. The counted area covered the whole region from 1.35 to 4.40 kb of each lane as shown by molecular marker.

Although the total amount of HBV RNA (full-length RNA and other forms) was similar in both n,n-DGJ-treated and untreated HepG2.2.15 cells (Fig. 5A, total RNA), the amount of HBV RNA detected in immune complexes of core sedimenting to high-density fractions was reduced three- to fourfold in the drug-treated cell lysates (Fig. 5A, fractions 5 and 6). This finding was also confirmed by quantification of the related bands in the n,n-DGJ-treated and untreated samples (Fig. 5B). Note that the samples analyzed in Fig. 5 may contain DNA, since DNase was not included in the preparation, and this could obscure band mobility. However, the decrease in the amount of HBV RNA recovered from the fractions of high sucrose density derived from drug-treated cultures was also observed by using immune-absorbance reverse transcription-PCR as described previously (24; data not shown).

We also note that some HBV nucleic acid was detected in the nucleocapsid-associated fractions of the sucrose gradient of the drug-treated cells (Fig. 5A, fractions 5 and 6), even though we were not able to detect HBV core polypeptide in these fractions by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 4B, lower panel, lanes 5 and 6). We assumed this to be due to the greater sensitivity of the hybridizations used for Fig. 5, but this requires further investigation.

The amount of HBV endogenous polymerase-associated core protein in HepG2.2.15 cells incubated with n,n-DGJ.

HBV DNA polymerase activity would also be expected to be present in intact nucleocapsids but not in unassembled core particles. Thus, fractions from the high-density region of the sucrose gradient, suspected to contain intact nucleocapsids, were tested for EPR as described by Bruss et al. (7). Briefly, after immunoprecipitation of the core proteins in each fraction as described in Materials and Methods, the samples were incubated with radioactively labeled deoxynucleotides, and the labeled HBV DNA product was isolated and resolved in 1% agarose gel and detected by radioautography by using a phosphorimager. As shown in Fig. 6, endogenous polymerase activity could be detected in the fractions associated with the assembled form of core protein (fractions 5 and 6) but not with the unassembled core proteins (fractions 1 to 3). This finding is in agreement with the earlier observation that HBV full-length (presumably pregenomic) RNA was largely restricted to this region of the gradient and, again, strongly supports the claim that the core particles in the high sucrose density are HBV nucleocapsids. The nature of the apparent activity seen in fraction 3 is unknown and was not consistently reproducible.

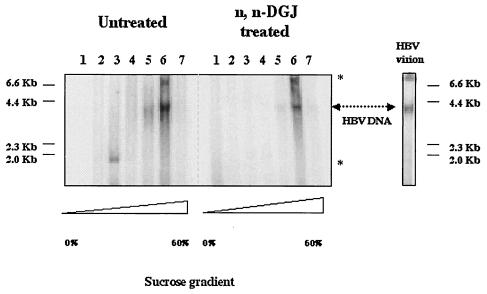

FIG. 6.

Endogenous DNA polymerase activity in assembled core particles. HepG2.2.15 cells treated or left untreated with n,n-DGJ were lysed and then centrifuged through sucrose gradients as described in Fig. 4 and 5 legends. Aliquots from each fraction of the sucrose gradients were incubated with protein G beads preabsorbed with anti-core antibody. After four washes, endogenous DNA polymerase activity assay (EPR) was performed as described by Bruss et al. (7). Labeled HBV DNA was resolved in a 1% agarose gel and visualized with a phosphorimager. The various sucrose densities of fractions are represented by triangles in the bottom. As a control, 1-μl portions of HBV virion particles (ca. 104) isolated from patients' serum were used in an EPR assay and run on an agarose gel (HBV virion). Arrows indicated the HBV DNA bands, respectively. The nonspecific bands obtained by EPR are indicated by asterisks.

In comparison with untreated cells, fractions 5 and 6 of the sucrose gradients derived from cells that had been incubated with n,n-DGJ contained 80% less core-associated polymerase activity. These data are consistent with fractions 5 and 6 containing polymerase-competent nucleocapsids and with a reduction in nucleocapsid abundance caused by n,n-DGJ incubation.

Core protein phosphorylation in n,n-DGJ-treated cells.

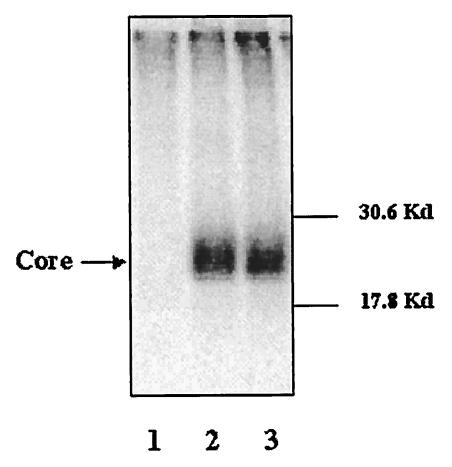

Core polypeptide can be modified by phosphorylation, which has been thought to play a role in the polypeptide's function (10, 17). Blocking the phosphorylation of core protein at specific sites prevents HBV encapsidation (10, 17, 19). It was therefore possible that the n,n-DGJ mediated reduction of nucleocapsid involved in core polypeptide phosphorylation. This possibility was explored by SDS-PAGE analysis of immunoprecipitates of core polypeptide from HepG2.2.15 cells after metabolic labeling of the cells with 32P. As shown in Fig. 7, there was no detectable difference in the amount of total phosphorylated core protein between n,n-DGJ-treated and untreated samples. This result implies that the phosphorylation of core protein is not affected by treatment with n,n-DGJ and that the n,n-DGJ-mediated reduction of nucleocapsid cells cannot be explained by a general impact upon core phosphorylation.

FIG. 7.

Phosphorylation of core protein in n,n-DGJ-treated cells. HepG2.2.15 cells treated with n,n-DGJ or left untreated were labeled with 32P. Core proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-core antibody from total cell lysates. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by using a phosphorimager. Lanes: 1, HepG2; 2, HepG2.2.15; 3, HepG2.2.15 plus n,n-DGJ.

DISCUSSION

n,n-DGJ is an alkylated imino sugar with a galactose-based head group that has anti-HBV and anti-bovine viral diarrhea virus activity (4, 5, 16, 25). Unlike alkylated imino sugars with glucose-based head groups, n,n-DGJ does not inhibit the cellular glycan processing enzymes such as glucosidase I and glucosidase II (16, 21-23, 25). Since the alkylated imino sugar, n,n-DGJ, reduced the amount of replicative forms of HBV DNA detected in HepG2.2.15 cells without apparently inhibiting either the viral polymerase or synthesis of viral envelope proteins, the possibility that nucleocapsid formation or stability was affected by this drug was explored. The data presented here show that the amounts of core protein, 3.2-kb HBV RNA (presumably core/pregenomic RNA), and endogenous viral polymerase activity cosedimenting in the high-density regions of sucrose gradients are reduced in amounts commensurate with the reduction of replicative viral DNA in HepG2.2.15 cells incubated with antiviral concentrations of n,n-DGJ compared to cells that were not incubated with compound. The reduction was not due to diminution of cell viability or of total amount of viral core protein, envelope proteins, or RNA synthesized. Taken together, these data suggest that n,n-DGJ caused a reduction in the amount of intact nucleocapsids.

Although these data identify putative steps in the virus life cycle that are affected by n,n-DGJ, the precise molecular mechanism of the depletion of nucleocapsid remains unclear. It is possible that the reduction of HBV nucleocapsid caused by n,n-DGJ depends upon preventing nucleocapsid formation. It is also possible that this reduction of nucleocapsid was due to the destabilization of assembled nucleocapsid. Further study to distinguish between these possibilities is needed.

Inhibition of morphogenesis and/or encapsidation of HBV pregenome is, to some extent, reminiscent of the antiviral action reported for alpha/beta interferon, which was also shown to block HBV replication in a DNA polymerase- and reverse transcription-independent manner (11, 12, 28, 31-33). We also note that, even though the data presented here suggest that core phosphorylation was not detectably affected by n,n-DGJ treatment, the methods used here cannot exclude an effect upon the phosphorylation level of particular sites in the core protein, since not all phosphorylated forms of the core polypeptide were resolved. Moreover, HBV core protein has three phosphorylation sites in its C-terminal sequence (S155, S162, and S170 in subtype ayw, which are equivalent to S157, S164, and S172 in subtype adw), and only site 162 has been shown to be consequential to encapsidation (10, 17, 19). Further study is necessary to completely rule out phosphorylation as a component in the n,n-DGJ-mediated antiviral mechanism.

Another difference between interferon and n,n-DGJ is whereas n,n-DGJ seems to reduce the assembled form of core protein at a high density of sucrose in the phosphorus labeling analysis, we did not find the same reduction after 24 h of treatment of HepG2.2.15 cells with alpha interferon (data not shown).

n,n-DGJ might block core protein aggregation and/or inhibit the stability of nucleocapsids. As a small molecule, n,n-DGJ might work by directly interacting with core protein, disturbing its aggregation or destabilizing the formed core particles and thus preventing HBV encapsidation. Recently, a small molecule, 5,5-bis-[8-(phenylamino)-1-naphthalenesulfonate] (bis-ANS), was demonstrated to inhibit the assembly of HBV nucleocapsid by directly interacting with core protein. bis-ANS binds to the core dimer, which causes a distortion of core subunit geometry, thereby inhibiting the assembly of normal capsid and promoting the assembly of noncapsid polymers (34). The effects of bis-Ans and n,n-DGJ upon HBV intracellular DNA levels in the absence of an effect upon polymerase enzyme and other viral gene products are therefore similar. It is thus tempting to speculate that their mechanisms of action may also be similar. While the present study was in revision, a series of compounds known as hetero-aryl-di-hydro-pyrimidines, which can deplete the HBV nucleocapsid from the HepG2.215 cell, were reported (8). How these compounds function is still under investigation. Perhaps in a manner similar to that of n,n-DGJ, these compounds either impede nucleocapsid formation or destabilize the formed nucleocapsids. Their effect would prevent the accumulation of HBV nucleocapsids. This anti-HBV mechanism might complement other drugs, such as nucleoside analogues, used in anti-HBV therapy.

n,n-DGJ-like molecules, which we refer to as alkovirs, are now in the phase I clinical trials for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in humans. Although the compounds clearly have antiviral activity and act in some ways that are analogous to and in other ways that are distinct from those of interferon, further study is needed to firmly identify the molecular mechanisms involved, which may be unique.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant V01 AI53884-02, Hepatitis B Foundation of America, and an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

We thank Tianlun Zhou (Thomas Jefferson University) for helpful comments and Melissa Hesley for help with manuscript preparation. We also thank Synergy, Inc. (Somerset, N.J.), for supplying n,n-DGJ.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beterams, G., and M. Nassal. 2001. Significant interference with hepatitis B virus replication by a core-nuclease fusion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8875-8883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birnbaum, F., and M. Nassal. 1990. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid assembly: primary structure requirements in the core protein. J. Virol. 64:3319-3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block, T. M., and R. Jordan. 2001. Iminosugars as possible broad spectrum anti-hepatitis virus agents: the glucovirs and alkovirs. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 12:317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Block, T. M., X. Lu, A. Mehta, J. Park, B. S. Blumberg, and R. Dwek. 1998. Role of glycan processing in hepatitis B virus envelope protein trafficking. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 435:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block, T. M., X. Lu, A. Mehta, J. Park, B. S. Blumberg, B. Tennant, M. Ebling, B. Korba, D. M. Lansky, G. S. Jacob, and R. A. Dwek. 1998. Treatment of chronic hepadnavirus infection in a woodchuck animal model with an inhibitor of protein folding and trafficking. Nat. Med. 4:610-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Block, T. M., X. Lu, F. M. Platt, G. R. Foster, W. H. Gerlich, B. S. Blumberg, and R. A. Dwek. 1994. Secretion of human hepatitis B virus is inhibited by the imino sugar N-butyldeoxynojirimycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2235-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruss, V., J. Hagelstein, E. Gerhardt, and P. R. Galle. 1996. Myristylation of the large surface protein is required for hepatitis B virus in vitro infectivity. Virology 218:396-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deres, K., C. Schroder, A. Paessens, S. Goldmann, H. Hacker, O. Weber, T. Kramer, U. Niewohner, U. Pleiss, J. Stoltefuss, E. Graef, D. Koletzki, R. Masantschek, A. Reimann, R. Jaeger, R. Gro, B. Beckermann, K. Schlemmer, D. Haebich, and H. Rubsamen-Waigmann. 2003. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by drug-induced depletion of nucleocapsids. Science 299:893-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funk, M. L., D. M. Rosenberg, and A. S. Lok. 2002. World-wide epidemiology of HbeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B and associated precore and core promoter variants. J. Viral Hepat. 9:52-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazina, E., J. Fielding, B. Lin, and D. Anderson. 2000. Core protein phosphorylation modulates pregenomic RNA encapsidation to different extents in human and duck hepatitis B viruses. J. Virol. 74:4721-4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidotti, L. G., A. Morris, H. Mendez, R. Koch, R. H. Silverman, B. R. Williams, and F. V. Chisari. 2002. Interferon-regulated pathways that control hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 76:2617-2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidotti, L. G., H. McClary, J. M. Loudis, and F. V. Chisari. 2000. Nitric oxide inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in the livers of transgenic mice. J. Exp. Med. 191:1247-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatton, T., S. Zhou, and D. N. Standring. 1992. RNA- and DNA-binding activities in hepatitis B virus capsid protein: a model for their roles in viral replication. J. Virol. 66:5232-5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui, E., K. L. Chen, and S. Lo. 1999. Hepatitis B virus maturation is affected by the incorporation of core proteins having a C-terminal substitution of arginine or lysine stretches. J. Gen. Virol. 20:2661-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui, E. K., Y. S. Yi, and S. J. Lo. 1999. Hepatitis B viral core proteins with an N-terminal extension can assemble into core-like particles but cannot be enveloped. J. Gen. Virol. 80:2647-2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan, R., O. V. Nikolaeva, L. Wang, B. Conyers, A. Mehta, R. A. Dwek, and T. M. Block. 2002. Inhibition of host ER glucosidase activity prevents Golgi processing of virion-associated bovine viral diarrhea virus E2 glycoproteins and reduces infectivity of secreted virions. Virology 295:10-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kann, M., B. Sodeik, A. Vlachou, W. H. Gerlich, and A. Helenius. 1999. Phosphorylation-dependent binding of hepatitis B virus core particles to the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 145:45-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koschel, M., D. Oed, T. Gerelsaikhan, R. Thomssen, and V. Bruss. 2000. Hepatitis B virus core gene mutations which block nucleocapsid envelopment. J. Virol. 74:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lan, Y. T., J. Li, W. Liao, and J. Ou. 1999. Roles of the three major phosphorylation sites of hepatitis B virus core protein in viral replication. Virology 259:342-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lott, L., B. Beames, L. Notvall, and R. E. Lanford. 2000. Interaction between hepatitis B virus core protein and reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 74:11479-11489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu, X., Y. Lu, R. Geschwindt, R. A. Dwek, and T. M. Block. 2001. Hepatitis B virus MHBs antigen is selectively sensitive to glucosidase-mediated processing in the endoplasmic reticulum. DNA Cell Biol. 20:647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu, X., A. Mehta, M. Dadmarz, R. Dwek, B. S. Blumberg, and T. M. Block. 1997. Aberrant trafficking of hepatitis B virus glycoproteins in cells in which N-glycan processing is inhibited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:2380-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu, X., A. Mehta, R. Dwek, T. Butters, and T. Block. 1995. Evidence that N-linked glycosylation is necessary for hepatitis B virus secretion. Virology 213:660-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu, X., T. Hazboun, and T. Block. 2001. Limited proteolysis induces woodchuck hepatitis virus infectivity for human HepG2 cells. Virus Res. 73:27-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehta, A., S. Carrouee, B. Conyers, R. Jordan, T. Butters, R. A. Dwek, and T. M. Block. 2001. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus DNA replication by imino sugars without the inhibition of the DNA polymerase: therapeutic implications. Hepatology 33:1488-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metzger, K., and R. Bringas. 1998. Proline-138 is essential for the assembly of hepatitis B virus core protein. J. Gen. Virol. 79:587-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nassal, M., and H. Schaller. 1996. Hepatitis B virus replication: an update. J. Viral Hepat. 3:217-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robek, M. D., S. F. Wieland, and F. V. Chisari. 2002. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by interferon requires proteasome activity. J. Virol. 76:3570-3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seeger, C., and W. S. Mason. 2000. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:51-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sells, M. A., A. Zelent, M. Shvartsman, and G. Acs. 1988. Replicative intermediates of hepatitis B virus in the HepG2 cells that produce infectius virions. J. Virol. 62:2836-3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suri, D., R. Schilling, A. R. Lopes, I. Mullerova, G. Colucci, R. Williams, and N. V. Naoumov. 2001. Non-cytolytic inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication in human hepatocytes. J. Hepatol. 35:790-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Togashi, H., S. Ohno, T. Matsuo, H. Watanabe, T. Saito, H. Shinzawa, and T. Takahashi. 2000. Interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin 1-beta suppress the replication of hepatitis B virus through oxidative stress. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 107:407-417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wieland, S. F., L. G. Guidotti, and F. V. Chisari. 2000. Intrahepatic induction of alpha/beta interferon eliminates viral RNA-containing capsids in hepatitis B virus transgenic mice. J. Virol. 74:4165-4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zlotnick, A., P. Ceres, S. Singh, and J. M. Johnson. 2002. A small molecule inhibits and misdirects assembly of hepatitis B virus capsids. J. Virol. 76:4848-4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]