Abstract

In herpes simplex virus 1-infected cells, a high level of α gene expression requires the transactivation of the genes by a complex containing the viral α transinducing factor (αTIF) and two cellular proteins. The latter two, HCF-1 and octamer binding protein Oct-1, are transcriptional factors regulated in a cell cycle-dependent manner. αTIF is a protein made late in infection but packaged with the virion to transactivate viral genes in newly infected cells. In light of the accumulation of large amounts of αTIF, the absence of α gene expression late in infection suggested the possibility that one or more transcriptional factors required for α gene expression is modified late in infection. Here we report that Oct-1 is posttranscriptionally modified late in infection, that the modification is mediated by the virus but does not involve viral protein kinases or cdc2 kinase activated by the virus late in infection, and that the modified Oct-1 has a reduced affinity for its cognate DNA site. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that modification of Oct-1 transcriptional factor could account at least in part for the shutoff of α gene expression late in infection.

In cells productively infected with herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), viral gene expression is regulated in a cascade fashion (18, 19, 39). The six α genes (α0, α4, α22, α27, α47, and US1.5) are expressed first, followed by the β and γ genes. To initiate efficient viral gene expression, a complex of cellular and viral proteins must interact with cognate sites present in promoter domains of α genes (22, 29). The key proteins are the cellular proteins HCF and the octamer binding protein Oct-1 and the viral α-transinducing factor (αTIF or VP16). The consensus sequence of the cognate site is 5′ NC GyATGnTAATGArATTCyTTGnGGG 3′ (21, 28). In the cognate site, Oct-1 binds to the octamer sequence ATGnTAAT. The complex of HCF-1 and αTIF bind the sequence immediately downstream of that bound by Oct-1 (8, 23, 24, 43). In the absence of cognate sites or αTIF, only a basal level of α gene expression ensues (42) y represents C or T; r represents A or G; and n represents A, G, C, or T.

The temporal cascade of viral gene expression involves downregulation of α gene expression and a sequential, coordinate increase in β and γ gene expression (18, 19). The decrease in the expression of α genes is readily observed in cells blocked from expressing β and γ genes. In light of the high amounts of αTIF accumulating in infected cells late in infection, the absence of α gene expression at late times is particularly striking. In the case of α4, its product, infected cell protein no. 4 (ICP4), binds to the cognate site situated across the α4 transcription initiation site to block its transcription (15, 27). Nothing is known of the mechanism by which other α genes are turned off, although it has been suggested that cellular machinery preferentially translates β and γ mRNAs. One potential answer to this puzzle is posttranslational modification of the proteins involved in the transcription of α genes. Thus, α gene promoters contain binding sites for Sp1, and it has been reported that Sp1 is modified in the course of HSV-1 infection (20). In this report we show that late in infection Oct-1 is posttranslationally modified and exhibits a reduced capacity to bind to its cognate sites.

Relevant to this report are the following: HCF-1 is a ubiquitously expressed protein that is associated with the chromatin (45). The temperature-sensitive BHK cell line tsBN67 contains a single amino acid missense mutation in HCF-1 (P134S) and at the nonpermissive temperature arrests in G1 (16). The same point mutation also prevents transcriptional activation by VP16. The transcription factor Oct-1 belongs to a family of transcription factors (Pit-1 and Unc-86) containing a conserved Pit, Onc, Unc (POU) domain (26, 29). The phosphorylation status of Oct-1 is regulated in a cell cycle manner. In nocodazole-treated (G2/M arrested) HeLa cell lysates, the electrophoretic mobility of Oct-1 is slower than that present in interphase cell lysates (38). Functionally, the mitotic phosphorylation of Oct-1 resulted in decreased ability to bind cognate sites in DNA (40). In in vitro assays, the decrease in binding capacity to DNA followed phosphorylation of Oct-1 by purified PKC (17). One scenario in which the virus could regulate a gene expression would be to modulate the cell cycle in order to regulate the activity of Oct-1 and HCF-1.

The studies described here stemmed from analyses of cellular function associated with later stages of HSV-1 replication. In the course of these studies, we noted that cells late in the HSV-1 replicative cycle acquire some of the characteristics of cells at the G2/M interphase. Thus, as reported elsewhere, the G2/M kinase cdc2 was active 8 h after HSV-1 infection despite the turnover of cyclins A and B, its cognate partners. cdc2 kinase is involved in the expression of a subset of γ2 genes exemplified by US11 (2, 4). Recent studies indicate that the viral DNA polymerase accessory factor UL42 interacts with cdc2. Moreover, cells transfected with UL42 show two characteristics of the G2/M phase, that is, active cdc2 kinase and active topoisomerase II (6, 7). The modification of E2F proteins and the hypophosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein that are at least in part responsible for the absence of S phase protein synthesis could also be viewed as a G2/M modification (3, 13, 41). An additional test of the hypothesis that in the course of infection the infected cells acquires G2/M characteristics was to determine whether HSV-1 modulated the activity of the cell cycle-regulated transcription factor Oct-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

HeLa cells were initially obtained from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% newborn calf serum. Telomerase-transformed human foreskin fibroblasts (pHFF) were initially obtained from T. Shenk (11). HSV-1(F) is the prototype HSV-1 wild-type strain used in this laboratory (14). R325, (lacking the carboxyl-terminal domain of ICP22), R7356 (UL13 deleted), and R7041 (US3 deleted) were described elsewhere (34, 36, 37).

Cell infection.

HeLa cells grown in 25-cm2 flasks were exposed to 2 × 107 PFU of appropriate virus in 1 ml of 199V (mixture 199 supplemented with 1% calf serum) on a rotary shaker at 37°C. After 2 h, the inoculum was replaced with 5 ml of fresh Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% calf serum. Flasks were incubated at 37°C until the cells were harvested at the time points indicated in Results. Time zero is defined as the time viral inoculum was added to the cells. For infection of pHFF, cells were grown to confluence and maintained for an additional 2 weeks. pHFF were exposed to virus in spent growth medium for 2 h and then maintained in virus-free spent growth medium until harvested at times indicated in Results.

Nocodazole treatment.

HeLa cells were exposed to 5 μg of nocodazole per ml for 18 h (Sigma). Cells were collected by two methods. In the first, the entire cell culture flask exposed to nocodazole was harvested. In the second, only cells that detached from nocodazole-treated flasks were harvested.

Immunoblotting.

Cells were harvested as follows. The medium was removed, and the cells were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), scraped into PBS, pelleted by centrifugation, and solubilized in high-salt lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA; 0.5% NP-40; 400 mM NaCl; 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate; 10 mM NaF; 2 mM dithiothreitol; 100 μg each of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and tolylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone per ml; 2 μg each of aprotonin and leupeptin per ml) on ice for 1 h. Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel loading buffer was added to the clarified supernatant (2% SDS, 50 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 2.75% sucrose, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, bromophenol blue). Equivalent amounts of protein per sample were subjected to electrophoresis on 6 or 10% bisacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked for 2 h with 5% nonfat dry milk, and reacted with the appropriate antibody.

Antibody against Oct-1 (Santa Cruz) was diluted 1:250 in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% Tween 20. Oct-1 was detected by using secondary antibody diluted 1:3,000 (goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase [AP]; Bio-Rad). Blots were incubated in AP buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 9.5; 100 mM NaCl; 5 mM MgCl2), followed by AP buffer containing BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) and nitroblue tetrazolium. The reaction was stopped with solution containing 100 mM Tris (pH 7.6) and 10 mM EDTA. All rinses were done with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20.

Cytoplasmic-nuclear fractionation.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractionation of cells was done as previously described (3). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were immunoblotted for Oct-1 as described above.

Oct-1 EMSA.

Nuclear fractions of mock, nocodazole exposed, or HSV-1-infected HeLa cells were used to bind 32P-labeled consensus Oct-1 DNA sequence by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as previously described (Santa Cruz) (3). Experiments were performed two ways. In the first set of experiments the amount of probe used remained constant and the amount of nuclear extract varied. In the second set of experiments, the amount of nuclear extract was fixed and the amount of 32P-labeled probe varied. Gels were analyzed by autoradiography and PhosphorImager analysis (Storm 860; Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

Oct-1 is modified in nocodazole-treated cells and HSV-1-infected cells.

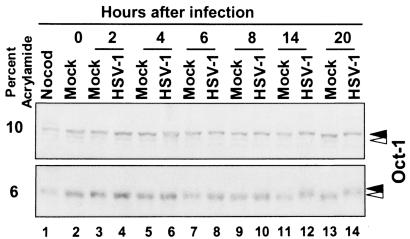

As noted in the introduction, Oct-1 has been reported to be modified in a cell cycle-dependent manner (38). Hyperphosphorylation of Oct-1 occurs in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. Previous studies indicated that HSV-1 infection induced cdc2 kinase activity late in infection, i.e., at 8 to 12 h postinfection (2). Therefore, we determined whether HSV-1 infection also resulted in the posttranslational modifications of Oct-1 at a time concordant with cdc2 activation in HSV-1-infected cells. HeLa cells were either mock or HSV-1(F) infected at time zero and then collected at various time points after infection. Lysates were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 6 or 10% bisacrylamide gels and reacted with anti-Oct-1 antibody. As shown in Fig. 1, Oct-1 present in mock-infected cells could not be differentiated with respect to electrophoretic mobility from that present in infected cells up to 8 h after infection. Oct-1 protein contained in cells harvested between 14 and 20 h after HSV-1 infection, however, migrated more slowly than that of mock-infected cells. The difference in electrophoretic mobility between HSV-1- and mock-infected lysates after 8 h postinfection was more readily apparent when they were separated on 6% bisacrylamide gels (Fig. 1, lower panel). As a positive control, cells were exposed to nocodazole, and the entire tissue culture flask was harvested. Oct-1 from nocodazole-exposed cells also migrated more slowly than mock cell lysate.

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot of Oct-1 during a 20-h time course of HSV-1 infection. HeLa cells were mock or HSV-1 infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times postinfection. Cells were also exposed to nocodazole (Nocod), and the entire flask was harvested. Lysates were separated on either 10% (upper panel) or 6% (lower panel) bisacrylamide gels and immunoblotted for Oct-1. White arrowhead, unmodified Oct-1; black arrowhead, HSV-1-modified Oct-1.

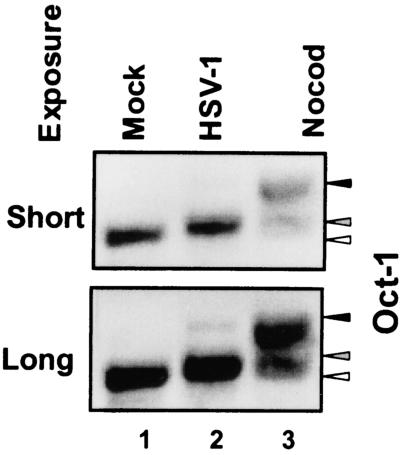

To further evaluate the migration of Oct-1 in HSV-1-infected cells and nocodazole-treated cells, nocodazole-treated culture flasks were vigorously shaken to detach cells. Cell lysates from mock-infected cells, cells harvested 18 h after HSV-1(F) infection, or detached cells from nocodazole-treated cultures were solubilized, electrophoretically separated on a denaturing 6% bisacrylamide gel, and reacted with anti-Oct-1 antibody. Figure 2 shows two exposures of the immunoblot to highlight the electrophoretic mobility of Oct-1. Mock-infected cell lysates had one Oct-1 reactive band that migrated the fastest (Fig. 2, open arrowhead). HSV-1-infected cell lysates and nocodazole-detached cell lysates contained two slower-migrating forms of Oct-1 (Fig. 2, solid arrowheads). It is of interest that HSV-1 infection or nocodazole treatment differed in the relative amounts of the slower-migrating forms. In HSV-1-infected cells, the faster-migrating form was the dominant species (Fig. 2, shaded arrowhead), whereas in nocodazole-exposed cells, the upper migrating form was the major Oct-1 form (Fig. 2, solid arrowhead).

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot of Oct-1 comparing nocodazole- or HSV-1-induced modification of Oct-1. HeLa cells were harvested 18 h after mock or HSV-1 infection. Nocodazole (Nocod)-exposed flasks were shaken to dislodge the cells. Only cells that detached by shaking the nocodazole-treated flasks were collected. Two exposures of the blot are shown to highlight the isoforms of Oct-1 in the various cell lysates. Open arrow, unmodified Oct-1; shaded arrow, HSV-1-modified Oct-1; solid arrow, Nocod-modified Oct-1.

Oct-1 is modified late in infection of contact-inhibited fibroblasts.

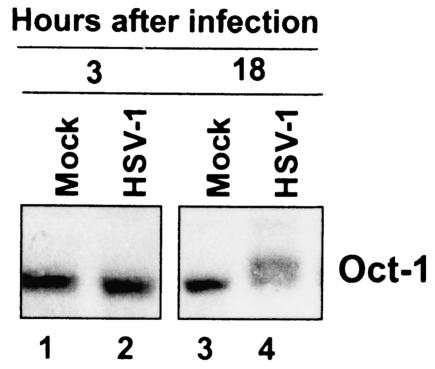

The above experiments were performed in cycling HeLa cells. An argument could be made that the virus-induced modifications of Oct-1 are simply a consequence of the normal cell cycle and not a specific activity of the virus. To address this issue, we infected noncycling, contact-inhibited pHFF and harvested cells 3 and 18 h after infection. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for Oct-1 (Fig. 3). Early in infection no difference was detected in the electrophoretic mobility of Oct-1 present in mock-infected and HSV-1-infected cells. At 18 h after infection, however, Oct-1 from HSV-1-infected lysates migrated more slowly than that contained in mock-infected cells. We conclude that the modification Oct-1 seen in HSV-1-infected lysates is specifically induced by HSV-1 infection.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot of Oct-1 from HSV-1-infected pHFF. Noncycling, contact-inhibited pHFF were mock infected or infected with HSV-1. Cells were harvested at 3 and 18 h postinfection. Cell lysates were then immunoblotted for Oct-1.

The viral protein kinases UL13 and US3 do not mediate Oct-1 modification.

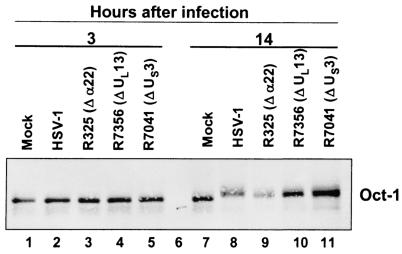

In uninfected cells, modifications of Oct-1 are mediated by cellular kinases (17, 40). HSV-1 encodes two major protein kinases, UL13 and US3. In some instances, modification of protein by the UL13 requires the presence of ICP22. To determine whether these proteins play a role in the posttranslational modification of Oct-1 late in infection, HeLa cells were infected with either the parent HSV-1(F) or mutant viruses from which ICP22 (R325), UL13 (R7356), or US3 (R7041) had been deleted. Cell lysates were harvested early (3 h) or late (14 h) in infection and immunoblotted for Oct-1 (Fig. 4). As expected, Oct-1 contained in cells harvested from mock-infected cells did not differ from those contained in either wild-type or mutant virus-infected cells 3 h postinfection. Late in infection, Oct-1 contained in wild-type or mutant virus-infected cells migrated more slowly than that of mock-infected cells. We conclude that ICP22 or the viral protein kinases do not play a role in the modification of Oct-1.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot of Oct-1 from HSV-1 mutant viruses. HeLa cells were mock-infected or infected with wild-type or mutant HSV-1. Three mutant viruses were tested: R325 (α22 deleted), R7356 (UL13 deleted), or R7041 (US3 deleted). Cells were harvested 3 or 14 h postinfection and immunoblotted for Oct-1.

The DNA-binding affinity of Oct-1 in HSV-1-infected cells is reduced.

We next determined whether HSV-1-induced posttranslational processing of Oct-1 resulted in decreased DNA binding to a consensus Oct-1 nucleotide sequence.

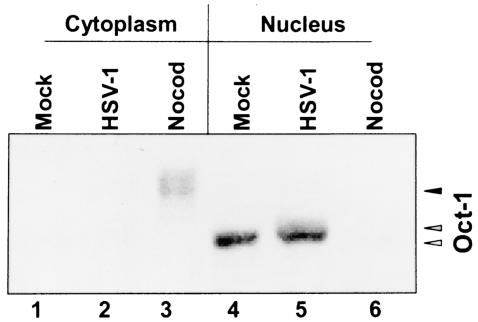

In the first series of experiments mock-infected and nocodazole-treated cells and cells were harvested 18 h after infection with HSV-1(F) and fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Aliquots of the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions prepared for the experiment described above were solubilized, subjected to electrophoresis in denaturing polyacrylamide gels, and reacted with anti-Oct-1 antibody. As shown in Fig. 5, Oct-1 contained in mock-infected or infected cells (18 h postinfection) was present primarily in the nuclear fraction. Whereas the amounts of Oct-1 protein appeared to be similar, a portion of the Oct-1 contained in lysates of nuclei of infected cells migrated more slowly than that of mock-infected cells. In contrast, in nocodazole-treated cells, Oct-1 was highly posttranslationally modified and accumulated primarily in the cytoplasm. Only a small fraction of the total Oct-1, largely indistinguishable from that of mock-infected cells, was present in the nuclear fraction.

FIG. 5.

Oct-1 immunoblot of the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. The cytoplasmic and nuclear lysates of the cells utilized in the EMSA assay were immunoblotted for Oct-1. Open arrow, unmodified Oct-1; shaded arrow, HSV-1-modified Oct-1; solid arrow, Nocod-modified Oct-1.

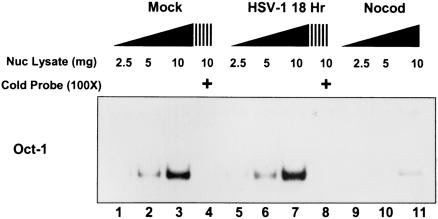

Nuclear lysates of mock-infected, nocodazole-treated, and HSV-1-infected cells were harvested 18 h postinfection and 2.5, 5, or 10 μg of nuclear lysate was reacted with 32P-labeled Oct-1 oligonucleotide and assayed by EMSA. Competition reaction mixtures contained a 100-fold excess of unlabeled Oct-1 oligonucleotide. As shown in Fig. 6, nuclear fraction lysates of mock-infected or HSV-1(F)-infected cells bound Oct-1 in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, excess unlabeled Oct-1 oligonucleotide competed effectively with the labeled probe (Fig. 6, lanes 4 and 8). As expected from the immunoblot in Fig. 5, nuclear lysates of nocodazole-treated cells bound the probe far less efficiently than the lysates of mock-infected or infected cells, since the protein was found primarily in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 6, lanes 9 to 11).

FIG. 6.

Oct-1 DNA electrophoretic mobility shift assay of nuclear lysates. Increasing amounts of nuclear lysate (2.5, 5, and 10 μg) were reacted with 32P-end-labeled DNA with an Oct-1 consensus binding site. Cells were harvested 18 h after mock or HSV-1 infection, as were nocodazole-exposed cells (Nocod). Competition with excess unlabeled DNA with an Oct-1 consensus binding site was also done with nuclear lysates (10 μg) from mock or HSV-1 infection (lanes 4 and 8).

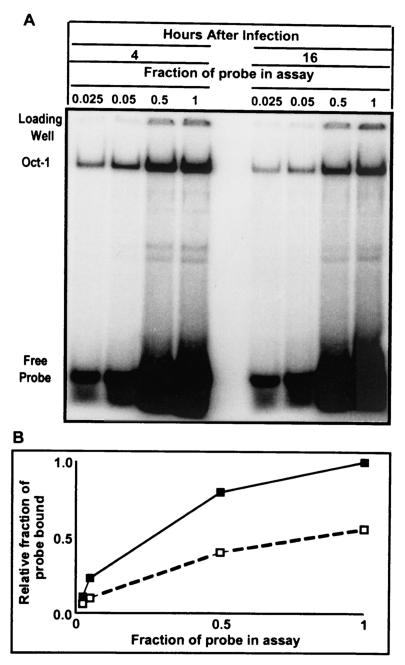

To determine whether Oct-1 present in cells late after infection with wild-type virus retained its capacity to bind to its cognate site in the DNA, aliquots containing 6 μg of lysates of infected cells harvested at 4 or 16 h after infection with HSV-1(F) were mixed with increasing amounts of labeled probe. The objective of the experiment was to approach saturation of available Oct-1 by its cognate DNA-binding site. As shown in Fig. 7A, increasing the amount of probe resulted in an increase in the amount of probe bound by Oct-1. The amount of labeled probe bound by Oct-1 was quantified with the aid of a phosphorimager, and the intensity of the signal of 1× probe bound by Oct-1 from lysates of cells harvested at 4 h after infection was set arbitrarily set at one. All other values were normalized with respect to that value. A plot of relative fraction of probe bound as a function of probe concentration in the reaction mixture is shown in Fig. 7B. The results indicate that near saturation values (1× probe), there was ∼2-fold more Oct-1-bound DNA at 4 h than at 16 h after infection.

FIG. 7.

(A) Oct-1 DNA EMSA of nuclear lysates with different concentrations of 32P-end-labeled DNA with an Oct-1 consensus binding site. A total of 6 μg of nuclear lysate from cells harvested at 4 and 16 h postinfection was reacted with various amounts of probe. The highest concentration of probe used was set at 1×. Probe concentrations used were 1/40 (0.025), 1/20 (0.05), and 1/2 (0.5) and 1. The shifted band is labeled Oct-1, and increasing amounts of free probe are seen at the bottom of the gel. (B) The Oct-1 shifted band was quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. The highest intensity signal was set at 1 (1× probe at 4 h postinfection), and all other intensities were calculated as a fraction of the highest signal. Solid squares, HSV-1 4 h postinfection; empty squares, HSV-1 16 h postinfection.

DISCUSSION

Sequential ordering of gene expression requires that genes contained in each class be turned on or off with a degree of precision. This can be accomplished in several ways, i.e., by incorporating specific response elements in promoter domains, regulating of mRNA half-life, shutting off gene expression at the promoter level, or modifying of transcriptional factors. The shut off of α gene expression appears to involve at least two mechanisms.

The first and most thoroughly investigated is the shutoff of α4 gene expression by ICP4, the product of the gene. ICP4 binds DNA, but the cognate site varies with respect to affinity. The consensus binding site is also the one associated with highest affinity and with shutoff rather than transactivation of viral gene expression. Sequences virtually identical to the consensus sequence occur at two locations: the transcription initiation site of ICP4 and open reading frame O/P. In this instance newly made ICP4 binds to these sites and turns off the transcription of the genes once the protein reaches a concentration optimal for viral replication. This mechanism accounts for the shutoff of α4 and open reading frame O/P genes but not for other α genes (15, 25, 27). Cognate sites varying in the degree of degeneracy abound throughout the genome (12, 30, 31, 44). The significance and role of these sites are not known. It has been reported that dephosphorylated ICP4 binds to sites within α promoters, whereas hyperphosphorylated ICP4 exhibits preferential binding for β and γ promoter complexes (32). ICP4 contains consensus phosphorylation sites for protein kinase A (PKA), PKC, casein kinase II, and cdc2 (4, 46); it is poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated and nucleotidylated (9, 10, 35). Early in infection, ICP4's pI is relatively basic and becomes progressively more acidic, a finding consistent with increased posttranslational modification (1, 5).

A second mechanism for downregulation of viral gene expression is through modification of cellular transcriptional factors. There are multiple putative Sp1 binding sites within α and β HSV-1 genes. Recent studies have shown that Sp1 transcription factor exists in a hyperphosphorylated state by 6 h after infection (20). The switch to a hyperphosphorylated Sp1 was dependent on both the expression of ICP4 and DNA synthesis. While the hyperphosphorylated Sp1 did not demonstrate appreciable differences in its ability to bind to its cognate nucleotide sequence in vitro, the modified Sp1 had reduced transcriptional activity in in vitro reporter assays. An implication of these results is that the virus downregulates Sp1-mediated transcription of α and β genes by modifying Sp1 at later times in infection.

We show here that another transcriptional factor, Oct-1, is modified in a similar fashion. As noted in the introduction, its partner αTIF accumulates in large amounts at late times after infection, and it could be expected that the presence of transcriptional factors at this stage of infection would induce a second wave of α gene expression. The results presented here that Oct-1 is modified late in infection and has a reduced capacity to bind DNA provide an explanation for the absence of an upsurge of α gene expression late in infection.

The modifications of Oct-1 in HSV-1-infected cells resemble in part those observed in nocodazole-treated cells (Fig. 1 and 2). Although both infection and nocodazole treatment caused posttranslational modification that reduced the electrophoretic mobility of Oct-1, they differed with respect to relative effects on the prevalent form accumulating in the corresponding cells. Whereas in nocodazole-treated cells the majority of Oct-1 migrated the slowest with a smaller amount of Oct-1 running at an intermediate form; in HSV-1-infected cells, the majority of Oct-1 migrated at the intermediate form (Fig. 2). Also, the modification of Oct-1 in HSV-1-infected cells was not dependent per se on cells cycling since Oct-1 was also modified late in infection in noncycling, contact-inhibited pHFF. Concordant with the modification of Oct-1, late in infection Oct-1 showed reduced affinity for its consensus DNA-binding site (Fig. 6 and 7).

Oct-1 is modified between 8 and 14 h after infection with HSV-1(F). The results presented here exclude two diverse mechanisms by which this modification could have occurred. First, we excluded the involvement of either UL13 or US3 protein kinase encoded by the virus. Second, we excluded the HSV-1-dependent activation of cdc2 kinase. As reported earlier, activation of cdc2 kinase occurs between 8 and 12 h after infection and is dependent on both ICP22 and UL13 protein kinases (2, 38). The results presented here show that Oct-1 was posttranslationally modified in cells infected with mutants lacking UL13 or the key portion of the α22 gene encoding ICP22. Thus, the mechanism by which the virus mediates the posttranslational processing of Oct-1 remains to be elucidated. Multiple cellular kinases have been implicated in the modification of Oct-1. PKA has been shown to phosphorylate Oct-1 within the DNA-binding POU homeodomain (40). In addition, Oct-2 is phosphorylated within the POU subdomain at residues that contain consensus phosphorylation sites for casein kinase II and PKA (33). While our results indicate that modified Oct-1 has a reduced affinity for its consensus DNA sequence, another consequence of the modification of Oct-1 may be reduced binding to αTIF produced later in infection. Also, the context of Oct-1 binding sites in the HSV-1 genome may influence binding of Oct-1 that is differentially modified.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Benetti and B. Taddeo for invaluable discussion.

These studies were supported by National Cancer Institute grants CA87661, CA83939, CA71933, CA78766, and CA88860 and by the U.S. Public Health Service.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann, M., D. K. Braun, L. Pereira, and B. Roizman. 1984. Characterization of herpes simplex virus 1 α proteins 0, 4, and 27 with monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 52:108-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Advani, S. J., R. Brandimarti, R. R. Weichselbaum, and B. Roizman. 2000. The disappearance of cyclins A and B and the increase in activity of the G2/M-phase cellular kinase cdc2 in herpes simplex virus 1-infected cells require expression of the α22/US1.5 and UL13 viral genes. J. Virol. 74:8-15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Advani, S. J., R. R. Weichselbaum, and B. Roizman. 2000. E2F proteins are posttranslationally modified concomitantly with a reduction in nuclear binding activity in cells infected with herpes simplex virus 1. J. Virol. 74:7842-7850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Advani, S. J., R. R. Weichselbaum, and B. Roizman. 2000. The role of cdc2 in the expression of herpes simplex virus genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10996-11001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Advani, S. J., R. Hagglund, R. R. Weichselbaum, and B. Roizman. 2001. Posttranslational processing of infected cell proteins 0 and 4 of herpes simplex virus 1 is sequential and reflects the subcellular compartment in which the proteins localize. J. Virol. 75:7904-7912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Advani, S. J., R. R. Weichselbaum, and B. Roizman. 2001. cdc2 cyclin-dependent kinase binds and phosphorylates herpes simplex virus 1 U(L)42 DNA synthesis processivity factor. J. Virol. 75:10326-10333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Advani, S. J., R. R. Weichselbaum, and B. Roizman. 2003. Herpes simplex virus 1 activates cdc2 to recruit topoisomerase IIalpha for post-DNA synthesis expression of late genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4825-4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babb, R., C. C. Huang, D. J. Aufiero, and W. Herr. 2001. DNA recognition by the herpes simplex virus transactivator VP16: a novel DNA-binding structure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4700-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaho, J. A., and B. Roizman. 1991. ICP4, the major regulatory protein of herpes simplex virus, shares features common to GTP-binding proteins and is adenylated and guanylated. J. Virol. 65:3759-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaho, J. A., N. Michael, V. Kang, N. Aboul-Ela, M. E. Smulson, M. K. Jacobson, and B. Roizman. 1992. Differences in the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation patterns of ICP4, the herpes simplex virus major regulatory protein, in infected cells and in isolated nuclei. J. Virol. 66:6398-6407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bresnahan, W. A., G. E. Hultman, and T. Shenk. 2000. Replication of wild-type and mutant human cytomegalovirus in life-extended human diploid fibroblasts. J. Virol. 74:10816-10818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLuca, N. A., A. M. McCarthy, and P. A. Schaffer. 1985. Isolation and characterization of deletion mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 in the gene encoding immediate-early regulatory protein ICP4. J. Virol. 56:558-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehmann, G. L., T. I. McLean, and S. L. Bachenheimer. 2000. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection imposes a G1/S block in asynchronously growing cells and prevents G(1) entry in quiescent cells. Virology 267:335-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ejercito, P., E. D. Kieff, and B. Roizman. 1968. Characterization of herpes simplex virus strains differing in their effects on social behavior of infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2:357-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faber, S. W., and K. W. Wilcox. 1988. Association of herpes simplex virus regulatory protein ICP4 with sequences spanning the ICP4 gene transcription initiation site. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:555-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goto, H., S. Motomura, A. C. Wilson, R. N. Freiman, Y. Nakabeppu, K. Fukushima, M. Fujishima, W. Herr, and T. Nishimoto. 1997. A single-point mutation in HCF causes temperature-sensitive cell-cycle arrest and disrupts VP16 function. Genes Dev. 11:726-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grenfell, S. J., D. S. Latchman, and N. S. Thomas. 1996. Oct-1 and Oct-2 DNA-binding site specificity is regulated in vitro by different kinases. Biochem. J. 315:889-893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honess, R. W., and B. Roizman. 1974. Regulation of herpesvirus macromolecular synthesis. I. Cascade regulation of the synthesis of three groups of viral proteins. J. Virol. 14:8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honess, R. W., and B. Roizman. 1975. Regulation of herpesvirus macromolecular synthesis: sequential transition of polypeptide synthesis requires functional viral polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72:1276-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, D. B., and N. A. DeLuca. 2002. Phosphorylation of transcription factor Sp1 during herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 76:6473-6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kristie, T. M., and B. Roizman. 1984. Separation of sequences defining basal expression from those conferring alpha gene recognition within the regulatory domains of herpes simplex virus 1 alpha genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:4065-4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kristie, T. M., and B. Roizman. 1987. Host cell proteins bind to the cis-acting site required for virion-mediated induction of herpes simplex virus 1 α genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:71-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kristie, T. M., J. H. LeBowitz, and P. A. Sharp. 1989. The octamer-binding proteins form multi-protein-DNA complexes with the HSV alpha TIF regulatory protein. EMBO J. 8:4229-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristie, T. M., and P. A. Sharp. 1990. Interactions of the Oct-1 POU subdomains with specific DNA sequences and with the HSV alpha-transactivator protein. Genes Dev. 4:2383-2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagunoff, M., and B. Roizman. 1995. The regulation of synthesis and properties of the protein product of open reading frame P of the herpes simplex virus 1 genome. J. Virol. 69:3615-3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latchman, D. S. 1999. POU family transcription factors in the nervous system. J. Cell. Physiol. 179:126-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leopardi, R., N. Michael, and B. Roizman. 1995. Repression of the herpes simplex virus 1 α 4 gene by its gene product (ICP4) within the context of the viral genome is conditioned by the distance and stereoaxial alignment of the ICP4 DNA binding site relative to the TATA box. J. Virol. 69:3042-3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackem, S., and B. Roizman. 1982. Structural features of the herpes simplex virus α gene 4, 0, and 27 promoter-regulatory sequences which confer α regulation on chimeric thymidine kinase genes. J. Virol. 44:939-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKnight, J. L. C., T. M. Kristie, and B. Roizman. 1987. Binding of the virion protein mediating α gene induction in herpes simplex virus 1 infected cells to its cis site requires cellular proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:7061-7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michael, N., D. Spector, P. Mavromara-Nazos, T. M. Kristie, and B. Roizman. 1988. The DNA-binding properties of the major regulatory protein alpha 4 of herpes simplex viruses. Science 239:1531-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michael, N., and B. Roizman. 1989. Binding of the herpes simplex virus major regulatory protein to viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:9808-9812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papavassiliou, A. G., K. W. Wilcox, and S. J. Silverstein. 1991. The interaction of ICP4 with cell/infected-cell factors and its state of phosphorylation modulate differential recognition of leader sequences in herpes simplex virus DNA. EMBO J. 10:397-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pevzner, V., R. Kraft, S. Kostka, and M. Lipp. 2000. Phosphorylation of Oct-2 at sites located in the POU domain induces differential down-regulation of Oct-2 DNA-binding ability. Biochem. J. 347:29-35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Post, L. E., and B. Roizman. 1981. A generalized technique for deletion of specific genes in large genomes: alpha gene 22 of herpes simplex virus 1 is not essential for growth. Cell 25:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preston, C. M., and E. L. Notarianni. 1983. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of a herpes simplex virus immediate-early polypeptide. Virology 131:492-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purves, F. C., W. O. Ogle, and B. Roizman. 1993. Processing of the herpes simplex virus regulatory protein α22 mediated by the UL13 protein kinase determines the accumulation of a subset of α and γ mRNAs and proteins in infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6701-6705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Purves, F. C., R. M. Longnecker, D. P. Leader, and B. Roizman. 1987. Herpes simplex virus 1 protein kinase is encoded by open reading frame US3 which is not essential for virus growth in cell culture. J. Virol. 61:2896-2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts, S. B., N. Segil, and N. Heintz. 1991. Differential phosphorylation of the transcription factor Oct1 during the cell cycle. Science 253:1022-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roizman, B., and D. M. Knipe. 2001. The replication of herpes simplex viruses, p. 2399-2459. In D. M. Knipe, P. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott/The Williams & Wilkins Co., New York, N.Y.

- 40.Segil, N., S. B. Roberts, and N. Heintz. 1991. Mitotic phosphorylation of the Oct-1 homeodomain and regulation of Oct-1 DNA binding activity. Science 254:1814-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song, B., J. J. Liu, K. C. Yeh, and D. M. Knipe. 2000. Herpes simplex virus infection blocks events in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Virology 267:326-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spector, D., F. Purves, and B. Roizman. 1991. Role of α-transinducing factor (VP16) in the induction of α genes within the context of viral genomes. J. Virol. 65:3504-3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stern, S., M. Tanaka, and W. Herr. 1989. The Oct-1 homoeodomain directs formation of a multiprotein-DNA complex with the HSV transactivator VP16. Nature 341:624-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson, R. J., and J. B. Clements. 1978. Characterization of transcription-deficient temperature-sensitive mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 91:364-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wysocka, J., P. T. Reilly, and W. Herr. 2001. Loss of HCF-1-chromatin association precedes temperature-induced growth arrest of tsBN67 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3820-3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia, K., N. A. DeLuca, and D. M. Knipe. 1996. Analysis of the phosphorylation sites of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4. J. Virol. 70:1061-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]