Abstract

Purpose of review

HIV-1 mucosal transmission plays a critical role in HIV-1 infection and AIDS pathogenesis. This review summarizes the latest advances in biological studies of HIV-1 mucosal transmission, highlighting the implications of these studies in the development of microbicides to prevent HIV-1 transmission.

Recent findings

New studies of initial HIV-1 infection using improved culture models updated the current view of mucosal transmission. Mechanistic studies enhanced our understanding of cell-cell transmission of HIV-1 mediated by the major target cells, including dendritic cells, CD4+ T cells, and macrophages. Increasing evidence indicated the significance of host factors and immune responses in HIV-1 mucosal infection and transmission.

Summary

Recent progress in HIV-1 mucosal infection and transmission enriches our knowledge of virus-host interactions and viral pathogenesis. Functional studies of HIV-1 interactions with host cells can provide new insights into the design of more effective approaches to combat HIV-1 infection and AIDS.

Keywords: HIV, mucosal, transmission, infection, biology

Introduction

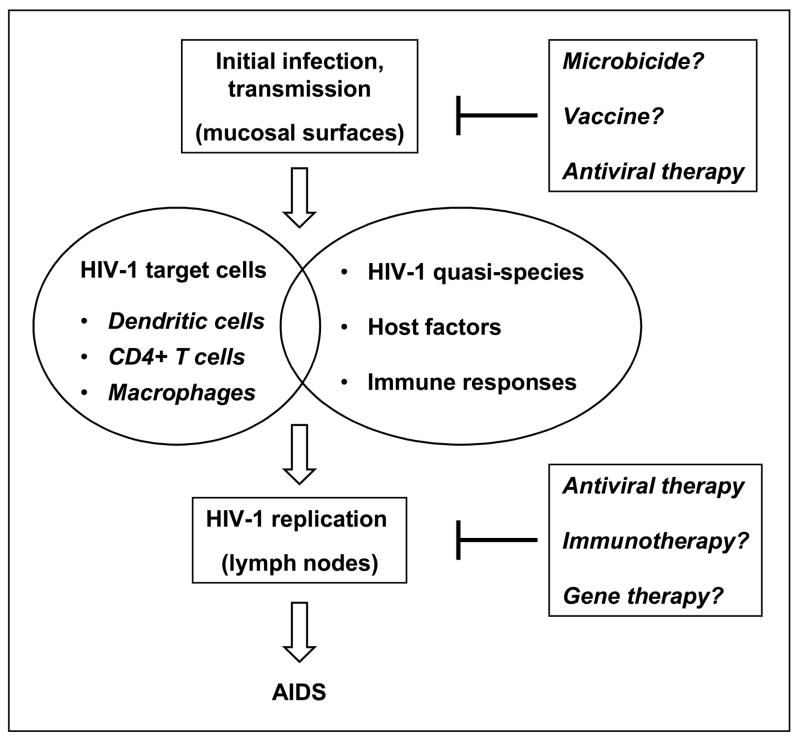

HIV-1 mucosal infection through sexual transmission plays a critical role in viral pathogenesis [1*–3*]. Defining the mechanisms of HIV-1 mucosal transmission can potentially help our combat against HIV-1/AIDS. Current antiretroviral therapies cannot eradicate HIV-1, and no effective vaccine is achievable soon; therefore, topical microbicides hold promise for HIV-1 prevention [2]. Recent studies of HIV-1 interactions with target cells provide new insights into understanding HIV-1 mucosal transmission. Host factors and immune responses are multifaceted contributors to HIV-1 infection and transmission (Figure 1). This review highlights the latest research advances in HIV-1 mucosal transmission, focusing on the mechanisms of cell-cell transmission of HIV-1.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of HIV-1 mucosal transmission.

HIV-1 mucosal transmission is a multifaceted process of virus-host interactions. Initial HIV-1 infection mainly occurs at the mucosal surfaces, involving epithelial cells, dendritic cells, CD4+ T cells, and macrophages. Migration of HIV-1-infected immune cells to lymph nodes spreads virus and establishes robust viral replication. Interactions between HIV-1 quasi-species, host factors, and immune responses contribute to the disease progression. Without an antiretroviral therapy, the vast majority of HIV-1-infected individuals eventually develop AIDS. Current antiretroviral treatment cannot eradicate HIV-1, and no effective vaccine is achievable soon. Thus, it is important to develop new interventions such as microbicides to prevent HIV-1 infection.

Initial events of HIV-1 mucosal infection and transmission

CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs) including Langerhans cells (LCs) are considered as early targets of HIV-1 infection and transmission in the vaginal mucosa [1*–3*]. However, the initial events in establishing vaginal HIV-1 infection are poorly characterized owing to the lack of a suitable model. Hladik et al. developed a culture model of epithelial sheets separated from human vaginal stroma to study HIV-1 entry and infection [4**]. HIV-1 enters intraepithelial CD4+ T cells by viral receptor-mediated fusion, leading to productive infection. By contrast, HIV-1 enters vaginal LCs via endocytosis mediated by multiple receptors. Intact HIV-1 particles were retained within LCs for 3 days without detectable viral replication. The LC-T-cell conjugates with concentrated HIV-1 were observed at 60 hr, but not at 2 hr after infection [4**]. These results suggest that initial HIV-1 infection of T cells is independent of LCs, while LC-mediated HIV-1 transmission to T cells may occur at the later stage of infection. Although HIV-1 replication may not be readily detected in LCs at the initial infection, it is possible that DCs hold infectious HIV-1 and augment viral replication upon interaction with CD4+ T cells [1*,5–11].

LCs have been speculated to support HIV-1 trans-infection through Langerin, a LC-specific C-type lectin. Unexpectedly, a recent study suggests that Langerin can be a natural barrier to HIV-1 infection [12*]. Langerin mediates HIV-1 internalization and intracellular degradation in skin-derived LCs, thereby inhibiting HIV-1 replication and transmission [12*]. However, it remains possible that a proportion of endocytosed HIV-1 escapes from the degradation, and initiates trans-infection of CD4+ T cells upon cell-cell contact. A recent report indicates that epithelial LCs in human skin explants account for >95% of HIV-1 dissemination [13*]. HIV-1 infection was detected only in LCs, but not dermal DCs and macrophages in the skin emigrants, suggesting that productive HIV-1 infection of LCs plays a critical role in occupational HIV-1 transmission [13*]. Moreover, CD34+ progenitor cell-derived LCs mediate HIV-1 trans-infection to CD4+ T cells [10,14].

Epithelial cells in the vaginal mucosa are also involved in HIV-1 mucosal transmission, although controversial results have been reported regarding whether HIV-1 can productively infect epithelial cells (review in [3*]). HIV-1 can penetrate the epithelial layer by transcytosis, although the efficiency of transcytosis appears to be very low (less than 0.02% of the initial HIV-1 inoculum) as indicated in a study using cultured primary genital epithelial cells [15]. HIV-1 may also be endocytosed by epithelial cells to initiate viral spread to target leukocytes [3*]. Additional studies are required to confirm this potential mechanism of HIV-1 mucosal transmission.

Mechanisms of DC-mediated HIV-1 trans-infection

Numerous studies have indicated an important role for DCs in HIV-1 mucosal transmission and viral pathogenesis (reviewed in [*1,16]). DCs transfer captured HIV-1 to cocultured CD4+ T cells by trans- and cis-infection pathways [1*]. Efficient HIV-1 trans-infection mediated by DCs requires contact between DCs and CD4+ target cells [7**]. The cell-cell junctions with concentrated HIV-1 are referred to as infectious/virological synapses (VS) [17,18], which facilitate HIV-1 transmission from DCs to CD4+ T cells.

HIV-1 attachment factors expressed on DCs contribute to viral capture and transmission. The best studied factor is the C-type lectin DC-SIGN (DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin), which partially accounts for HIV-1 transmission by certain DC subsets (reviewed in [1*]). However, DC-mediated HIV-1 trans-infection occurs independently of DC-SIGN [1*,7**,19]. A recent study indicates that syndecan-3, a DC-specific heparan sulfate proteoglycan, binds HIV-1 through viral envelope glycoprotein (Env) and enhances HIV-1 trans-infection [20]. Accordingly, microbicides that block HIV-1 interactions with DC-SIGN and syndecan-3 might prevent DC-mediated viral transmission.

Cellular proteins and signaling pathways modulate DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission by interacting with DC-SIGN. Leukocyte-specific protein 1 (LSP1), an F-actin binding protein involved in leukocyte motility, binds to DC-SIGN and directs internalized HIV-1 to the proteasome in DCs for viral degradation [21]. Silencing LSP1 expression in DCs enhances HIV-1 transmission to CD4+ T cells, suggesting that HIV-1 trafficking through the cytoskeleton is important for viral transmission [21]. HIV-1 or DC-SIGN-specific antibodies activate DC-SIGN signaling through the leukemia-associated Rho guanine nucleotide-exchange factor (LARG), which increases Rho-GTPase activity [22]. Activation of LARG in DCs facilitates HIV-1 transmission to CD4+ T cells by enhancing VS formation between DCs and T cells [22]. Moreover, interactions of DC-SIGN with different human pathogens including HIV-1 activate the Raf-1 kinase-dependent acetylation to modulate Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling [23]. Given the importance of TLRs in DC-initiated adaptive immunity, this DC-SIGN-mediated signaling pathway may regulate the immune responses to various pathogens.

HIV-1 trafficking in DCs contributes to viral transmission and the formation of VS between DCs and T cells [7**,8,10,19,21,24–26]. We found that intracellular trafficking inhibitors partially block viral transmission [7**]. Our results indicate that both cell surface-bound and internalized HIV-1 contribute to DC-mediated trans-infection [7**]. Compared with immature DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission, viral trafficking in mature DCs appears to play a more important role in trans-infection [5,7**,8,10,24,26]. However, Cavrois et al. reported that DC-mediated HIV-1 trans-infection mainly derives from DC surface-bound viruses [14]. Although it is difficult to directly compare these results owing to the different experimental approaches, the dynamic trafficking and recycling of internalized HIV-1 to DC surfaces could also mediate viral transmission. This should be an important consideration in studying DC-HIV-1 interactions and in developing effective microbicides.

HIV-1-bearing DCs likely interact with different T cell subsets in vivo and mediate viral transfer. DCs may play a decisive role in differential susceptibility of HIV-1 infection in naïve and memory CD4+ T cells [27]. R5 HIV-1 is most efficiently transmitted to effector memory T cells, which are the major targets for HIV-1 replication and abundantly present in mucosal tissues, while X4 HIV-1 is preferentially transmitted to naïve T cells by DCs. Thus, DCs may contribute to the initial burst of HIV-1 replication in effector memory T cells, and to the replication of X4 HIV-1 in naïve T cells at the late stage of infection [27].

HIV-1 cis-infection of DCs and viral transmission

Similar to mucosal HIV-1 transmission, the selection for R5 HIV-1 strains occurs during parenteral transmission. However, the cell types responsible for this selection have not been defined. Using sorted blood mononuclear cells to model HIV-1 parenteral infection, Cameron et al. reported preferential HIV-1 infection of myeloid DCs and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) relative to monocytes and resting CD4+ T cells [28*]. The selective infection of blood DCs by R5 HIV-1 and enhanced viral transmission to CD4+ T cells suggest a potential mechanism of R5 HIV-1 selection during parenteral transmission.

HIV-1 infection of DCs can lead to virus production and long-term viral transmission, implying that HIV-1-infected DCs are viral reservoirs in vivo [1*,9**,16,29*]. To better understand HIV-1 cis-infection of DCs, it is important to define viral entry pathway that leads to productive infection in DCs. Previous studies [30–33] and our recent data [9**,34] indicate that productive infection of HIV-1 in DCs requires fusion-mediated viral entry. HIV-1 enters DCs predominately through endocytosis; however, endocytosed HIV-1 cannot initiate productive HIV-1 infection [4**,9**,34]. The majority of endocytosed HIV-1 in intracellular compartments in DCs will eventually be degraded [5,7**,30,35]; however, when HIV-1-bearing DCs encounter CD4+ T cells prior to viral degradation, efficient HIV-1 trans-infection of CD4+ T cells can occur in vitro [5–11]. Furthermore, we compared cis- and trans-infections of HIV-1 mediated by immature DCs and various stimulus-induced mature DCs, and found that these two infection pathways are dissociable [9**]. Therefore, various DC subsets in vivo may differentially contribute to HIV-1 dissemination via dissociable cis- and trans-infection.

HIV-1 proteins and host factors influence viral replication in DCs, and regulate viral transmission efficiency. We recently reported that HIV-1 Nef promotes HIV-1 transfer from DCs to CD4+ T cells [29*]. Nef-induced CD4 downregulation in HIV-1-infected-DCs correlates with enhanced viral transmission. Interestingly, blocking CD4 on DCs with specific antibodies enhances DC-mediated HIV-1 trans-infection [29*]. These results suggest that CD4 and Nef can modulate HIV-1 transmission by DCs. Moreover, HIV-1 replication in DCs occurs through a tetraspanin-containing compartment enriched in adaptor protein 3 (AP-3), and viral production is dependent on AP-3 [26].

Host immune responses contribute to the attenuated disease progression of HIV-2 infection [36]. The lack of productive HIV-2 infection in DCs may help to explain the less pathogenic HIV-2 infection relative to HIV-1 infection. Duvall et al. showed that various HIV-2 isolates could not efficiently infect myeloid DCs or pDCs, and myeloid DCs failed to transfer HIV-2 to autologous CD4+ T cells [37]. However, HIV-2-specific CD4+ T cells contain more viral DNA than those of other specificities in vivo [37], suggesting that DCs are not an important contributor to infection of HIV-2-specific CD4+ T cells in vivo.

HIV-1 cell-cell transmission by CD4+ T cells and macrophages

HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cells can initiate efficient cell-cell transmission to uninfected T cells through Env- and cytoskeleton-dependent VS [38*,39]. Cell-associated transfer of HIV-1 is estimated to be 92- to 18,600-fold more efficient than that of cell-free virus, and VS-mediated HIV-1 transfer is resistant to patient-derived neutralizing antisera [38*]. Cellular proteins that enhance immunological synapse formation, such as intercellular adhesion molecules and ZAP-70 kinase, also facilitate VS formation and HIV-1 transmission between CD4+ T cells [40,41]. Interestingly, HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cells can transfer viruses to uninfected T cells through intercellular membrane nanotubes [42*], suggesting that HIV-1 usurps intercellular connections between immune cells to enhance viral spread. Further studies are required to examine if these newly identified mechanisms also occur in DC- and macrophage-mediated HIV-1 transmission to CD4+ T cells.

HIV-1-infected macrophages act as viral reservoirs, and play an important role in HIV-1 pathogenesis. HIV-1-infected macrophages transmit viruses to CD4+ T cells through VS [43,44**]. Studying HIV-1 assembly in macrophages may aid in development of novel antivirals or microbicides. HIV-1 assembles mainly at the plasma membrane [45,46] or into an intracellular plasma membrane domain in macrophages [47]. HIV-1 can also bud and accumulate in nonacidic endosomes of macrophages [48*], suggesting that HIV-1 survives within a nonacidic assembly compartment by preventing intracellular degradation. HIV-1 may use the same strategy to survive in infected-DCs. In fact, DCs have mechanisms to control phagosomal acidification to preserve antigen cross-presentation [49].

Inhibitors that block HIV-1 infection in macrophages might be potential candidates for microbicides or antivirals. Carbohydrate-binding agents have been shown to inhibit HIV-1 infection in macrophages and prevent viral transmission to CD4+ T cells [50]. Moreover, HIV-1 protects infected macrophages from apoptosis by viral Env-induced signaling; therefore, pharmacological restoration of apoptotic sensitivity for HIV-1-infected macrophages could be a potential therapeutic strategy [51]. Since HIV-1 infection elevates Akt kinase activity in macrophages, PI3K/Akt inhibitors might be used as novel antivirals to block HIV-1 infection in macrophages [52].

Host factors influencing HIV-1 mucosal transmission

Host factors can promote or inhibit HIV-1 infection and transmission, thereby influencing viral infection and AIDS progression [53*]. In the screen of host factors that affect the efficiency of sexual viral transmission, Münch et al. identified that human semen-derived amyloid fibrils dramatically enhance HIV-1 in vitro infection [54**]. The semen-derived amyloid fibrils might play an important role in sexual transmission of HIV-1, and could represent a new target of microbicide development. By contrast, Sabatté et al. reported that human seminal plasma markedly inhibits HIV-1 transmission to CD4+ T cells mediated by DCs and DC-SIGN-expressing cells [55]. These discrepant results might derive from the different experimental approaches and procedures, which require further investigation.

DC restriction of HIV-1 infection reflects innate antiviral immunity. HIV-1 replication in CD4+ T cells is inhibited by pDCs through the secretion of interferon alpha (IFN-α) and other unidentified antiviral factors [56,57*]. High levels of viral replication in vivo are associated with cell death of pDCs, and pDCs from HIV-1-infected individuals, who maintain low levels of viremia without antiretroviral therapy, suppress HIV-1 replication ex vivo [57*]. Moreover, HIV-1 infection in monocytes, monocyte-derived DCs, and pDCs can be partially blocked by the antiretroviral factor APOBEC3G (apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3G) and its family molecules [58–60], suggesting that DCs, particularly pDCs, could be imyportant mediators of innate anti-HIV immunity. However, HIV-1 gp120 inhibits TLR9-mediated activation in pDCs, resulting in a decreased secretion of IFN-α and inflammatory cytokines [61*]. Further studies of anti-HIV mechanisms in DCs may help to develop new strategies against HIV/AIDS.

HIV-1 exploits the cytoskeletal network to facilitate viral infection and dissemination [62]. We observed that an intact cytoskeleton network is required for efficient DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission (Wang JH and Wu L, unpublished data). It might be worth exploring if cytoskeleton inhibitors can be developed as reversible or topical agents to block HIV-1 transmission in vivo. The actin cytoskeleton also contributes to T cell activation by forming immunological synapses (IS) between antigen-presenting cells and T cells [63]. The IS appear to share structural similarities with the VS, and may play a role in HIV-1 pathogenesis [64]. HIV-1 facilitates cell-cell transmission by promoting VS formation, whereas HIV-1 infection impairs IS formation [65]. Theoretically, blocking the formation of VS may prevent DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission to CD4+ T cells; however, the structure and function of IS should be protected to maintain anti-HIV immunity.

Recently, over 250 cellular proteins required for HIV-1 replication have been identified through a functional genomic screen, and only 36 of them are previously associated with HIV-1 infection [66**]. A cell-membrane protein that inhibits HIV-1 release has been recently discovered and termed tetherin (also called CD317, BST-2 or HM1.24), whereas HIV-1 Vpu counteracts tetherin’s antiviral function [67**,68]. These new findings shed light on the development of potential strategies for anti-HIV interventions.

Host immunity and HIV-1 mucosal transmission

DCs play a crucial role in the generation and the regulation of adaptive immunity [69]. DCs efficiently present HIV-1 antigens to T cells via MHC-I- and MHC-II-restricted pathways [35,70,71]. However, HIV-1 and host proteins can mediate viral immune evasion and affect AIDS pathogenesis. For example, gp120 mannoses induce immunosuppressive responses from DCs [72], and DCs capture and transfer antibody-neutralized HIV-1 to CD4+ T cells via DC-SIGN [73]. A recent study identifies that the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 and its chemokine agonist CCL3L1 (also called macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha, or MIP1α) are major determinants of cell-mediated immunity to HIV-1, suggesting these host factors influence viral pathogenesis through cell-mediated immunity and viral entry-independent mechanisms [74**].

Chronic activation of the immune system is a hallmark of progressive HIV-1 infection and AIDS. Microbial translocation can be a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV-1 infection [75], suggesting chronic immune activation during HIV-1 infection is associated with a compromised gut mucosal surface. HIV-1 replication in gut-associated lymphoid tissue mediates massive depletion of gut CD4+ T cells, which contribute to HIV-1 immune pathogenesis. A recent study reports that HIV-1 Env binds to and signals through integrin α4β7, the gut mucosal homing receptor for peripheral T cells [76*]. Engagement of α4β7 on CD4+ T cells via HIV-1 gp120 activates leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 [76*], which can facilitate VS formation and HIV-1 transmission.

Conclusion

A better understanding of the biology of HIV-1 mucosal transmission can facilitate the development of prophylactic and therapeutic approaches against HIV-1 infection. Recent research advances in HIV-1 mucosal transmission provide new insights into the design of effective microbicides, antiviral drugs, and vaccines. Although laboratory-adapted HIV-1 strains and monocyte-derived DCs/macrophages are commonly used in studies, these in vitro systems cannot fully recapitulate the physiological conditions in HIV-1 infection. Thus, clinical HIV-1 isolates, blood/mucosal DCs, tissue macrophages, and animal models should be used for confirming studies.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Michael Dwinell and the members of the author’s laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions. The author’s laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI068493) and the Campbell Foundation. The author apologizes to all those whose work has not been cited as a result of space limitations.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as: * of special interest, ** of outstanding interest.

- 1.*.Wu L, KewalRamani VN. Dendritic-cell interactions with HIV: infection and viral dissemination. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nri1960. A review summarizes HIV-1 interactions with dendritic cells, focusing on the mechanisms of DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lederman MM, Offord RE, Hartley O. Microbicides and other topical strategies to prevent vaginal transmission of HIV. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:371–382. doi: 10.1038/nri1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.*.Morrow G, Vachot L, Vagenas P, et al. Current concepts of HIV transmission. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0005-x. An interesting review highlights current understanding of HIV-1 mucosal transmission. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.**.Hladik F, Sakchalathorn P, Ballweber L, et al. Initial events in establishing vaginal entry and infection by human immunodeficiency virus type-1. Immunity. 2007;26:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.007. This study develops an improved organ culture model to examine initial HIV-1 infection at the vaginal mucosa, showing different HIV-1 entry pathways and infection efficiencies of Langerhans cells and CD4+ T cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turville SG, Santos JJ, Frank I, et al. Immunodeficiency virus uptake, turnover, and 2-phase transfer in human dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;103:2170–2179. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turville SG, Vermeire K, Balzarini J, et al. Sugar-binding proteins potently inhibit dendritic cell human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection and dendritic-cell-directed HIV-1 transfer. J Virol. 2005;79:13519–13527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13519-13527.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.**.Wang JH, Janas AM, Olson WJ, et al. Functionally distinct transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mediated by immature and mature dendritic cells. J Virol. 2007;81:8933–8943. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00878-07. A functional comparative study shows distinct efficiencies and mechanisms of HIV-1 trans-infection mediated by immature and mature DCs. This study also reports DC-target cell contact is required for DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izquierdo-Useros N, Blanco J, Erkizia I, et al. Maturation of blood derived dendritic cells enhances HIV-1 capture and transmission. J Virol. 2007;81:7559–7570. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02572-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.**.Dong C, Janas AM, Wang J-H, et al. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in immature and mature dendritic cells reveals dissociable cis-and trans-infection. J Virol. 2007;81:11352–11362. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01081-07. This report is a comparative analysis of cis- and trans-infections of HIV-1 mediated by different DC subsets, suggesting that these two infection pathways are dissociable. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fahrbach KM, Barry SM, Ayehunie S, et al. Activated CD34-derived Langerhans cells mediate transinfection with human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2007;81:6858–6868. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02472-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank I, Stossel H, Getti A, et al. A fusion inhibitor prevents dendritic cell (DC) spread of immunodeficiency viruses but not DC activation of virus-specific T cells. J Virol. 2008;82(11):5329–39. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01987-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.*.de Witte L, Nabatov A, Pion M, et al. Langerin is a natural barrier to HIV-1 transmission by Langerhans cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:367–371. doi: 10.1038/nm1541. This study shows that Langerin mediates HIV-1 internalization and intracellular degradation in skin-derived LCs, thereby inhibiting HIV-1 replication and transmission. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.*.Kawamura T, Koyanagi Y, Nakamura Y, et al. Significant virus replication in Langerhans cells following application of HIV to abraded skin: relevance to occupational transmission of HIV. J Immunol. 2008;180:3297–3304. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3297. A report indicates that epithelial LCs account for >95% of HIV-1 dissemination in human skin explants. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavrois M, Neidleman J, Kreisberg JF, et al. In vitro derived dendritic cells trans-infect CD4 T cells primarily with surface-bound HIV-1 virions. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bobardt MD, Chatterji U, Selvarajah S, et al. Cell-free human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcytosis through primary genital epithelial cells. J Virol. 2007;81:395–405. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01303-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piguet V, Steinman RM. The interaction of HIV with dendritic cells: outcomes and pathways. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald D, Wu L, Bohks SM, et al. Recruitment of HIV and its receptors to dendritic cell-T cell junctions. Science. 2003;300:1295–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.1084238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piguet V, Sattentau Q. Dangerous liaisons at the virological synapse. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI22812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boggiano C, Manel N, Littman DR. Dendritic cell-mediated trans-enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity is independent of DC-SIGN. J Virol. 2007;81:2519–2523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01661-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Witte L, Bobardt M, Chatterji U, et al. Syndecan-3 is a dendritic cell-specific attachment receptor for HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19464–19469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith AL, Ganesh L, Leung K, et al. Leukocyte-specific protein 1 interacts with DC-SIGN and mediates transport of HIV to the proteasome in dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:421–430. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodges A, Sharrocks K, Edelmann M, et al. Activation of the lectin DC-SIGN induces an immature dendritic cell phenotype triggering Rho-GTPase activity required for HIV-1 replication. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:569–577. doi: 10.1038/ni1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gringhuis SI, den Dunnen J, Litjens M, et al. C-type lectin DC-SIGN modulates Toll-like receptor signaling via Raf-1 kinase-dependent acetylation of transcription factor NF-kappaB. Immunity. 2007;26:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia E, Pion M, Pelchen-Matthews A, et al. HIV-1 trafficking to the dendritic cell-T-cell infectious synapse uses a pathway of tetraspanin sorting to the immunological synapse. Traffic. 2005;6:488–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiley RD, Gummuluru S. Immature dendritic cell-derived exosomes can mediate HIV-1 trans infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:738–743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507995103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia E, Nikolic DS, Piguet V. HIV-1 replication in dendritic cells occurs via a tetraspanin-containing compartment enriched in AP-3. Traffic. 2008;9:200–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groot F, van Capel TM, Schuitemaker J, et al. Differential susceptibility of naive, central memory and effector memory T cells to dendritic cell-mediated HIV-1 transmission. Retrovirology. 2006;3:52. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.*.Cameron PU, Handley AJ, Baylis DC, et al. Preferential infection of dendritic cells during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of blood leukocytes. J Virol. 2007;81:2297–2306. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01795-06. This report shows the selective infection of blood DCs by R5-tropic HIV-1 and enhanced viral transmission to CD4+ T cells, suggesting a role of DCs in R5 HIV-1 selection during parenteral transmission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.*.Wang JH, Janas AM, Olson WJ, et al. CD4 coexpression regulates DC-SIGN-mediated transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2007;81:2497–2507. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01970-06. This study suggests that HIV-1 Nef enhances DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission, and that CD4 coexpression modulates DC-SIGN-mediated viral transmission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nobile C, Petit C, Moris A, et al. Covert human immunodeficiency virus replication in dendritic cells and in DC-SIGN-expressing cells promotes long-term transmission to lymphocytes. J Virol. 2005;79:5386–5399. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5386-5399.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavrois M, Neidleman J, Kreisberg JF, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus fusion to dendritic cells declines as cells mature. J Virol. 2006;80:1992–1999. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1992-1999.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burleigh L, Lozach P-Y, Schiffer C, et al. Infection of dendritic cells (DCs), not DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of human immunodeficiency virus, is required for long-term transfer of virus to T cells. J Virol. 2006;80:2949–2957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2949-2957.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pion M, Arrighi JF, Jiang J, et al. Analysis of HIV-1-X4 fusion with immature dendritic cells identifies a specific restriction that is independent of CXCR4 levels. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:319–323. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janas AM, Dong C, Wang J-H, et al. Productive infection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in dendritic cells requires fusion-mediated viral entry. Virology. 2008;375(2):442–51. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moris A, Nobile C, Buseyne F, et al. DC-SIGN promotes exogenous MHC-I-restricted HIV-1 antigen presentation. Blood. 2004;103:2648–2654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schindler M, Munch J, Kutsch O, et al. Nef-mediated suppression of T cell activation was lost in a lentiviral lineage that gave rise to HIV-1. Cell. 2006;125:1055–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duvall MG, Lore K, Blaak H, et al. Dendritic cells are less susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) infection than to HIV-1 infection. J Virol. 2007;81:13486–13498. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00976-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.*.Chen P, Hubner W, Spinelli MA, et al. Predominant mode of human immunodeficiency virus transfer between T cells is mediated by sustained Env-dependent neutralization-resistant virological synapses. J Virol. 2007;81:12582–12595. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00381-07. This study estimates that cell-associated transfer of HIV-1 through VS can be 92- to 18,600-fold more efficient than that of cell-free virus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jolly C, Mitar I, Sattentau QJ. Requirement for an intact T-cell actin and tubulin cytoskeleton for efficient assembly and spread of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2007;81:5547–5560. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01469-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jolly C, Mitar I, Sattentau QJ. Adhesion molecule interactions facilitate human immunodeficiency virus type 1-induced virological synapse formation between T cells. J Virol. 2007;81:13916–13921. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01585-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sol-Foulon N, Sourisseau M, Porrot F, et al. ZAP-70 kinase regulates HIV cell-to-cell spread and virological synapse formation. EMBO J. 2007;26:516–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.*.Sowinski S, Jolly C, Berninghausen O, et al. Membrane nanotubes physically connect T cells over long distances presenting a novel route for HIV-1 transmission. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:211–219. doi: 10.1038/ncb1682. A study shows HIV-1 transfer by membrane nanotubes formed between CD4+ T cells. The efficiency of HIV-1 transmission by nanotubes remains to be determined when compare to VS-mediated viral transfer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Groot F, Welsch S, Sattentau QJ. Efficient HIV-1 transmission from macrophages to T cells across transient virological synapses. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.**.Gousset K, Ablan SD, Coren LV, et al. Real-time visualization of HIV-1 GAG trafficking in infected macrophages. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:e1000015. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000015. A new study suggests that HIV-1-infected macrophages spread viruses to CD4+ T cells through VS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jouvenet N, Neil SJ, Bess C, et al. Plasma membrane is the site of productive HIV-1 particle assembly. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Welsch S, Keppler OT, Habermann A, et al. HIV-1 buds predominantly at the plasma membrane of primary human macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e36. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deneka M, Pelchen-Matthews A, Byland R, et al. In macrophages, HIV-1 assembles into an intracellular plasma membrane domain containing the tetraspanins CD81, CD9, and CD53. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:329–341. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.*.Jouve M, Sol-Foulon N, Watson S, et al. HIV-1 buds and accumulates in “nonacidic” endosomes of macrophages. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.011. An ultrastructural study suggests that HIV-1 survives within a nonacidic assembly compartment preventing intracellular degradation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Savina A, Jancic C, Hugues S, et al. NOX2 controls phagosomal pH to regulate antigen processing during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2006;126:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pollicita M, Schols D, Aquaro S, et al. Carbohydrate-binding agents (CBAs) inhibit HIV-1 infection in human primary monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) and efficiently prevent MDM-directed viral capture and subsequent transmission to CD4+ T lymphocytes. Virology. 2008;370:382–391. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swingler S, Mann AM, Zhou J, et al. Apoptotic killing of HIV-1-infected macrophages is subverted by the viral envelope glycoprotein. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1281–1290. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chugh P, Bradel-Tretheway B, Monteiro-Filho CM, et al. Akt inhibitors as an HIV-1 infected macrophage-specific anti-viral therapy. Retrovirology. 2008;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.*.Lama J, Planelles V. Host factors influencing susceptibility to HIV infection and AIDS progression. Retrovirology. 2007;4:52. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-52. A comprehensive review on host factors affecting susceptibility to HIV infection and AIDS progression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.**.Münch J, Rucker E, Standker L, et al. Semen-derived amyloid fibrils drastically enhance HIV infection. Cell. 2007;131:1059–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.014. This study reports that human semen-derived amyloid fibrils can enhance HIV-1 infectivity by more than 100,000-fold under the experimental conditions. The mechanisms underlying the formation of the amyloid fibrils and the enhancement of HIV-1 infectivity remain to be elucidated. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sabatté J, Ceballos A, Raiden S, et al. Human seminal plasma abrogates the capture and transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to CD4+ T cells mediated by DC-SIGN. J Virol. 2007;81:13723–13734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01079-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Groot F, van Capel TM, Kapsenberg ML, et al. Opposing roles of blood myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in HIV-1 infection of T cells: transmission facilitation versus replication inhibition. Blood. 2006;108:1957–1964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-010918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.*.Meyers JH, Justement JS, Hallahan CW, et al. Impact of HIV on cell survival and antiviral activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000458. A study suggests that plasmacytoid DCs can be important mediators of innate anti-HIV-1 immunity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pion M, Granelli-Piperno A, Mangeat B, et al. APOBEC3G/3F mediates intrinsic resistance of monocyte-derived dendritic cells to HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2887–2893. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng G, Greenwell-Wild T, Nares S, et al. Myeloid differentiation and susceptibility to HIV-1 are linked to APOBEC3 expression. Blood. 2007;110:393–400. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang FX, Huang J, Zhang H, et al. APOBEC3G upregulation by alpha interferon restricts human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in human peripheral plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:722–730. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.*.Martinelli E, Cicala C, Van Ryk D, et al. HIV-1 gp120 inhibits TLR9-mediated activation and IFN-{alpha} secretion in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3396–3401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611353104. This study suggests that HIV-1 gp120 antagonizes the innate anti-HIV-1 activity of plasmacytoid DCs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Naghavi MH, Goff SP. Retroviral proteins that interact with the host cell cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dustin ML. Cell adhesion molecules and actin cytoskeleton at immune synapses and kinapses. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fackler OT, Alcover A, Schwartz O. Modulation of the immunological synapse: a key to HIV-1 pathogenesis? Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:310–317. doi: 10.1038/nri2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thoulouze MI, Sol-Foulon N, Blanchet F, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection impairs the formation of the immunological synapse. Immunity. 2006;24:547–561. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.**.Brass AL, Dykxhoorn DM, Benita Y, et al. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008;319:921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. A new study reports over 250 cellular proteins that are required for HIV-1 replication. Despite using a HeLa-cell-derived cell line in the genomic screen, this study provides new insights into further studies of HIV-host interactions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.**.Neil SJ, Zang T, Bieniasz PD. Tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by HIV-1 Vpu. Nature. 2008;451:425–430. doi: 10.1038/nature06553. A host protein termed tetherin is found to inhibit retrovirus release from the cell surface, while HIV-1 Vpu counteracts tetherin’s antiviral function. Thus, inhibition of Vpu function could be a potential therapeutic strategy against HIV-1 infection. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van Damme N, Goff D, Katsura C, et al. The interferon-induced protein BST-2 restricts HIV-1 release and is downregulated from the cell surface by the viral Vpu protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3 :45–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iwasaki A. Mucosal dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:381–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moris A, Pajot A, Blanchet F, et al. Dendritic cells and HIV-specific CD4+ T cells: HIV antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and viral transfer. Blood. 2006;108:1643–1651. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-006361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jones L, McDonald D, Canaday DH. Rapid MHC-II antigen presentation of HIV type 1 by human dendritic cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:812–816. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shan M, Klasse PJ, Banerjee K, et al. HIV-1 gp120 mannoses induce immunosuppressive responses from dendritic cells. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e169. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Montfort T, Nabatov AA, Geijtenbeek TB, et al. Efficient capture of antibody neutralized HIV-1 by cells expressing DC-SIGN and transfer to CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2007;178:3177–3185. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.**.Dolan MJ, Kulkarni H, Camargo JF, et al. CCL3L1 and CCR5 influence cell-mediated immunity and affect HIV-AIDS pathogenesis via viral entry-independent mechanisms. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1324–1336. doi: 10.1038/ni1521. This study suggests that host factors CCL3L1 and CCR5 influence viral pathogenesis through cell-mediated immunity and viral entry-independent mechanisms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.*.Arthos J, Cicala C, Martinelli E, et al. HIV-1 envelope protein binds to and signals through integrin alpha4beta7, the gut mucosal homing receptor for peripheral T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:301–309. doi: 10.1038/ni1566. This report indicates that engagement of α4β7 on CD4+ T cells via HIV-1 gp120 activates of LFA-1, which facilitates VS-mediated cell-cell transmission of HIV-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]