Abstract

Laminin-binding to dystroglycan in the dystrophin glycoprotein complex2 causes signaling through dystroglycan-syntrophin-grb2-SOS1-Rac1-PAK1-JNK. Laminin-binding also causes syntrophin tyrosine phosphorylation to initiate signaling. The kinase responsible was investigated here. PP2 and SU6656, specific inhibitors of Src family kinases, decreased the amount of phosphotyrosine-syntrophin and decreased active Rac1 in laminin-treated myoblasts, myotubes or skeletal muscle microsomes. c-Src and c-Fyn both phosphorylate syntrophin and inhibition of either with specific siRNAs diminish syntrophin phosphorylation. When the rat gastrocnemius was contracted, Rac1 activation increased compared to the relaxed control muscle and Rac1 co-localized with β-dystroglycan. Similar results were obtained when the muscle was stretched. Contracted muscle also contained more activated c-Jun N-terminal Kinase, JNKp46. E3, an expressed protein containing only laminin domains LG4–5, increased proliferation of myoblasts and PP2 prevented cell proliferation. In addition, Src family kinases co-localized with activated Rac1 and with laminin-Sepharose in solid-phase binding assays. Thus, contraction, stretching, or laminin-binding cause Src-family kinase recruitment to the dystrophin glycoprotein complex, activating Rac1 and inducing downstream signaling. The DGC likely represents a mechanoreceptor in skeletal muscle regulating muscle growth in response to muscle activity. Src-family kinases play an initiating and critical role.

In skeletal muscle, dystrophin, dystroglycan and syntrophins are found in the dystrophin glycoprotein complex, whose defects cause muscular dystrophies. Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the absence of dystrophin and the most common progressive muscle-wasting disease in human (1). Congenital muscular dystrophy results from alterations in laminin-dystroglycan interaction (2). Either type of muscular dystrophy would disrupt the normal DGC interaction with laminin. We showed that laminin binding causes signaling through dystroglycan-syntrophin-grb2-SOS1-Rac1-PAK1-JNK that ultimately results in the phosphorylation of c-jun on Ser63 (3). We have proposed that this or other cell signaling, which results from the DGC-laminin interaction, may serve a role in these pathologies. Although many activities of the DGC are known, its function is unclear.

Laminin is an αβγ heterotrimer. It binds to both dystroglycan and integrins in five globular domains (i.e., LG domains) of laminin’s α-subunit. Laminin α2-chain LG modules 4–5 bind to the acidic polysaccharide chains of αDG (4); the integrin binding site in the LG1–5 region has not been mapped in detail (5). The binding site for αDG also localizes to the LG4–5 modules of laminin α5, however the binding site for α3β1 and α6β1 integrins localizes to LG1–3 (6). In laminin-1 (α1β1γ1), it is LG4 that binds αDG (7). In the studies presented here, the LG4–5 region of laminin α1 was expressed and is referred to as the E3 protein (8).

Laminin, or E3, binds to α-dystroglycan and initiates cell signaling cascades. Recently, E3 has been shown to substitute for laminin and cause tyrosine phosphorylation of syntrophin and alter grb2-binding to initiate signaling (9). E3- or laminin-binding also results in heterotrimeric G-protein binding to the DGC (10). Laminin-binding to αDG also activates the PI3K/Akt pathway and inhibits apoptosis (11).

One essential problem with this laminin-induced signaling is that laminin is tightly bound by αDG in vivo and it is unlikely that it ever dissociates. We hypothesize that it is not binding that normally activates signaling but rather stresses put on the laminin-dystroglycan interaction during muscle stretching or contraction that may initiate this signaling. Here, we test this hypothesis. We show that Rac1 co-localizes with β-dystroglycan on the sarcolemma of the rat gastrocnemius and Rac1 and JNK-p46 become active when muscles stretch or tension develops, showing that these stimuli can also initiate the same kinds of signaling as does laminin-binding. Furthermore, the kinase which tyrosine phosphorylates syntrophin had not been identified and experiments presented here show that Src family member kinases phosphorylate syntrophin. Src family tyrosine kinases also comprise a major group of cellular signal in various tissue types. These kinases regulate cellular functions including mitogenesis, cell cycle progression, adhesion and migration (12). The consequence of this signaling was also investigated. In C2C12 myoblasts laminin-E3 increased proliferation and this was inhibited by inhibitors of the Src family kinases. Src family kinases also co-localize with activated Rac1 in solid-phase binding assays when laminin is present. PP2 or SU6656, specific inhibitors of Src family kinases, decreased the amount of activated Rac1 and inhibited activated Src (autophosphorylated on Tyr 416). These results indicate that laminin-binding or muscle contraction/stretching causes Src-family recruitment to the DGC, syntrophin phosphorylation and initiates Rac1 activation and downstream signaling. This may be an important contributor to the signals that maintain muscle mass and the DGC may function as a mechanoreceptor.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Antibodies against phospho-Tyr, phospho-Src (Tyr416), c-Src, c-Fyn and integrin β1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rac1 and αDG antibodies were from Upstate Biotechnology. βDG was the generous gifts of Dr. Tamara C. Petrucci (Laboratorio di Biologia Cellulare, Instituto Superiore di Sanita, Via le Regina Elena, Roma, Italy). Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L)-horseradish peroxidase conjugate was from Sigma. Goat anti-mouse IgM (H+L)-horseradish peroxidase conjugate and goat anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Southern Biotechnology Associate Inc. Mouse laminin-1 was obtained from Collaborative Biomedical Products. PP3, PP2 and SU6656 were from Calbiochem-Novabiochem. Purified, active c-Src was purchased from Millipore-Upstate Cell Signaling. The mouse C2C12 myogenic cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). All other chemicals were of the highest purity available commercially.

Merosin was purified from 15 g of rat skeletal muscle as described by other (13).

E3 was purified from the hLNa1-E3 293 (HEK293) cell line transfected with the LG4–5 domains of human laminin α1, which was generated as described (8). Briefly, the cultured medium was harvested at 24 and 48 h. Diluted medium was loaded onto a 25 ml DEAE-Sepharose column whose outlet was connected a 5 ml Hi-trap (Pharmacia) heparin column. The eluted protein was detected by absorption at 280 nm or by gel electrophoresis (14). The concentration of E3 was determined (15) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Syntrophin and other fusion proteins

Syntrophin and Syntrophin A were produced as His-Tag fusion proteins and purified as previously described (16). Additionally, an αSG fusion protein was produced. Mouse RNA (1 µg) was used with random hexamers to produce a crude cDNA template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the Invitrogen DNA cycle kit and AMV reverse transcriptase. This was then used as a template for PCR using 10 pmol each of 5′-ATGGCGGCGGCCGCG (αSG 255–269) and 5′-CGGAATTCAGTGCTGGTCCAGGATG (αSG 1400–1418) as upstream and downstream primers. The bold sequence shows an EcoRI restriction site engineered for directional cloning. This was then first cloned into pMALc and then subcloned into pET28a and expressed in E. coli strain BL21, and positive clones were selected by miniprep and restriction mapping. Positive clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing and the protein was expressed and purified as described for the syntrophin fusion proteins.

siRNA transfection

2–4 × 105 C2C12 cells per well of a 6-well plate were transiently transfected with 10 µM of a control siRNA or with siRNAs specific for c-Src, c-Fyn or mixtured c-Src and c-Fyn siRNAs (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, California, USA). The transfection was according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Cells were harvested 48 h after incubation and washed with PBS. Cells were then lysed in RIPA (PBS, 1% SDS, 0.5% DOC and 1% NP-40) buffer and this was used for several experiments.

In vitro c-Src assay

Catalytically active c-Src from Upstate was used for in vitro phosphorylation following the procedure of Dowler, et al. (17) except that 25 µM Na4VO3 and 2.5 mM β-glycerophosphate was included as phosphatase inhibitors and 25 µM ATP was used. The final assay contained 20,000 cpm γ-32P-ATP, 5 µg of either syntrophin A or α-sarcoglycan, and 1 unit of c-Src. Assays (20 µl) were incubated for 10 min at 30°C. Samples were mixed with an equal volume of twice concentrated SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and after electrophoresis the gel was dried and used to expose photographic film for autoradiography.

Cell culture and cell proliferation assay

Mouse C2C12 cells were grown and maintained as myoblasts in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. For cell growth experiments, cells were plated in six-well plates and grown in medium containg E3 for 24 h or 48 h. Cells were counted after trypsinization using trypan blue. Propidium iodide was incorporated to nuclei after using 70% methanol to fix the cells. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. For experiments with myotubes, myoblast were cultured as above to 80% confluence and then the medium was changed to DMEM containing 1% FBS and grown for a further 5 days to allow fusion to myotubes. Myotubes or myoblast were washed with PBS and harvested by adding 1 ml of trypsin-EDTA solution (0.05% trypsin, 0.02% EDTA in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution, HBSS) for 5 min at 37°C. The cells were then immediately suspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS and removed from the plate. This treatment has been previously shown to also deplete the cells of laminin but not DGC components (9)

Preparation of contracted muscle

Sprague-Dawley rats (200–300 g) were used. Animals were housed in light-and temperature-controlled quarters where they received food and water ad libitum. Animals were anesthetized with isofluorane for surgery and tissue removal. Muscle was contracted by electric stimulation of the sciatic nerve (10 V, 10 Hz, 1 min) in one hindleg and either immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed and embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound at −20°C. Samples were stored at −80°C until use. In other experiments, one Achilles tendon was severed and the muscle was stretched to approximately 125% of its relaxed length by pulling on the tendon with hemostats for 1 min. In all experiments, the contralateral muscle was treated the same except that it was not stimulated. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Preparations of Microsomes from Skeletal Muscle and C2C12 Cells

3 g of frozen rabbit or 0.5 g of frozen rat skeletal muscle were cut into very fine slices using a razor blade and then homogenized in 7 volumes of pyrophosphate buffer (20 mM Na4P2O7, 20 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.303 M sucrose, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.0) in the presence of a cocktail of protease inhibitor as described previously (3). The homogenate was centrifuged at 13000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was centrifuged for 30 min at 32500 g to pellet muscle microsomes. For making C2C12 cell membranes, 106–107 cells were suspended in 100–500 µl of pyrophosphate buffer in the presence of a cocktail of protease inhibitor and homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer with type B pestle. The sample was centrifuged at 13000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 400,000 g for 30 min to pellet microsomes. The pellets were suspended in buffer K (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl) or 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl if they were to be treated with heparin-Sepharose and then suspended in buffer K.

Skeletal muscle membranes were also depleted laminin by using heparin-Sepharose (3) for some experiments. The microsomes were divided into two portions. The larger portion was incubated with heparin-Sepharose, the smaller portion with Sepharose 4B as a negative control for 1 h at 4°C on a wheel type tube rotator providing gentle mixing. After incubation, the beads were removed by slow speed centrifugation (2000 rpm in a microfuge). For culture cell, the cells were either scraped from the plates, to retain endogenous laminin, or removed with trypsin-EDTA solution (0.05% trypsin, 0.02% EDTA in HBSS) for 10 min at 37°C, which depletes laminin (9).

Preparation of Laminin or E3–Sepharose

Preactivated CNBr Sepharose (Sigma) was swollen by suspension in ice-cold 1 mM HCl for 15 min and washed with 1 mM HCl on a sintered glass filter. 100 µg of laminin or E3 in coupling buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.3) was mixed with 0.5 ml of the swollen, activated Sepharose in a screwcap plastic tube on a wheel rotator overnight at 4°C. The laminin- or E3-Sepharose was washed with blocking buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, 0.5 M NaCl pH 8.0) and again mixed overnight. Control-Sepharose was prepared in the same way except without any added protein.

Fusion protein-PAK1 and Preparation of PAK1-Sepharose

A chimeric fusion of GST and the p21-binding domain of PAK1 was expression in E. coli strain BL21 and purified by affinity chromatography on glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma) as described elsewhere (18). After washing, some of the beads were used for pull-down experiments without eluting the GST-PAK1. For other uses, the protein was eluted with glutathione and its purity was determined by 12% SDS-PAGE using the method of Laemmli (14). The protein concentration was determined (15) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Pull-down Assays

Untreated or PP3, PP2 and SU6656 pretreated membranes from rabbit, rat and C2C12 cell were incubated with control-Sepharose, laminin- or E3-Sepharose, or GST-PAK1-Sepharose in buffer K (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2) containing 1 mM GTPγS, 1 mM ATP and 1 mM CaCl2 with or without laminin for 1 h at 4°C with gentle mixing and then solubilized by adding 2x Dig (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M sucrose, 2% digitonin). The samples were centrifuged at 2000 rpm in a microfuge at room temperature for 1 min. The resins were washed three times with buffer K containing 1x Dig. The bound protein was eluted using 60 µl of twice concentrated Laemmli SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were heated for 5 min at 95°C and centrifuged for 5 min at room temperature to remove the resin. The supernatants were applied to electrophoresis on a 4–20% Bio Rad ready gel SDS-PAGE and electroblotted to nitrocellulose. The blots were blocked with 5% skim milk in TTBS (0.2% Tween-20, 20mM Tris, 0.5M NaCl, pH 7.5). The blot was incubated with anti-Rac1 (Upstate Biotechnology, 1:1000), anti-phospho-Src (Tyr416, Upstate 1:1000) anti-Src and anti-Fyn (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000) or anti-αDG (Upstate, 1:1000) at room temperature for 1 h. Goat anti-rabbit IgG- (1:10000) or goat anti-mouse IgG or IgM (H+L) - horseradish perixodase conjugate (1:3000) was used as a secondary antibody as required by the experiment. The blots were then developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence method (3).

Loading control

For loading control, the blots were stained with ponceau red S (0.2% ponceau in 3% TCA) before blocking with 5% skim milk to confirm that the same amount protein was loaded to each well. In other experiments, the blot was stripped and reprobed with a different antibody, typically against β-actin or syntrophin. In all cases, equal loads were confirmed.

Inhibitor Blockade

C2C12 cells were cultured with PP3 (5–10 µM), PP2 (2.5–10 µM) or SU6656 (10 µM) for various times (from 6 hrs to 12 hrs) as specified in the figure legends at 37°C in six-wells plate. The cells were collected using trypsin-EDTA and were washed three times with PBS. 106 cells in 100 µl PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail were incubated with or without 3 µg of laminin at 37°C for an additional hour.

Immunocytochemistry

Muscle cross sections (10 µm) were prepared with a cryostat and collected on gelatin-coated glass slides. To minimize autofluorescence, sections were sliced, stained and viewed on the same day. Sections were fixed in tissue fixative (Histochoice) for 5 min at room temperature. The slides were washed three times with Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate buffer. PAK-GST (10 µg) fusion protein in 100µl of PBS was overlaid on the slides of sections for 15 min at room temperature and then the slides were washed three times with KH buffer. The rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GST (1:500) or βDG (1:100) and the mouse monoclonal antibody against Rac1 (1:50) were diluted in KH buffer with 3% BSA and were added to the slides. The slides were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in a humidified container and then washed with KH buffer. The goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L)-Alexa Fluor 488 and tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC) conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Fc) secondary antibodies (1:100) were added. Washed slides were mounted with 50% glycerol mounting medium. The immunofluorescence in the muscle sections was observed with a Zeiss LSM 5 confocal microscope using Ar and HeNe lasers.

Results

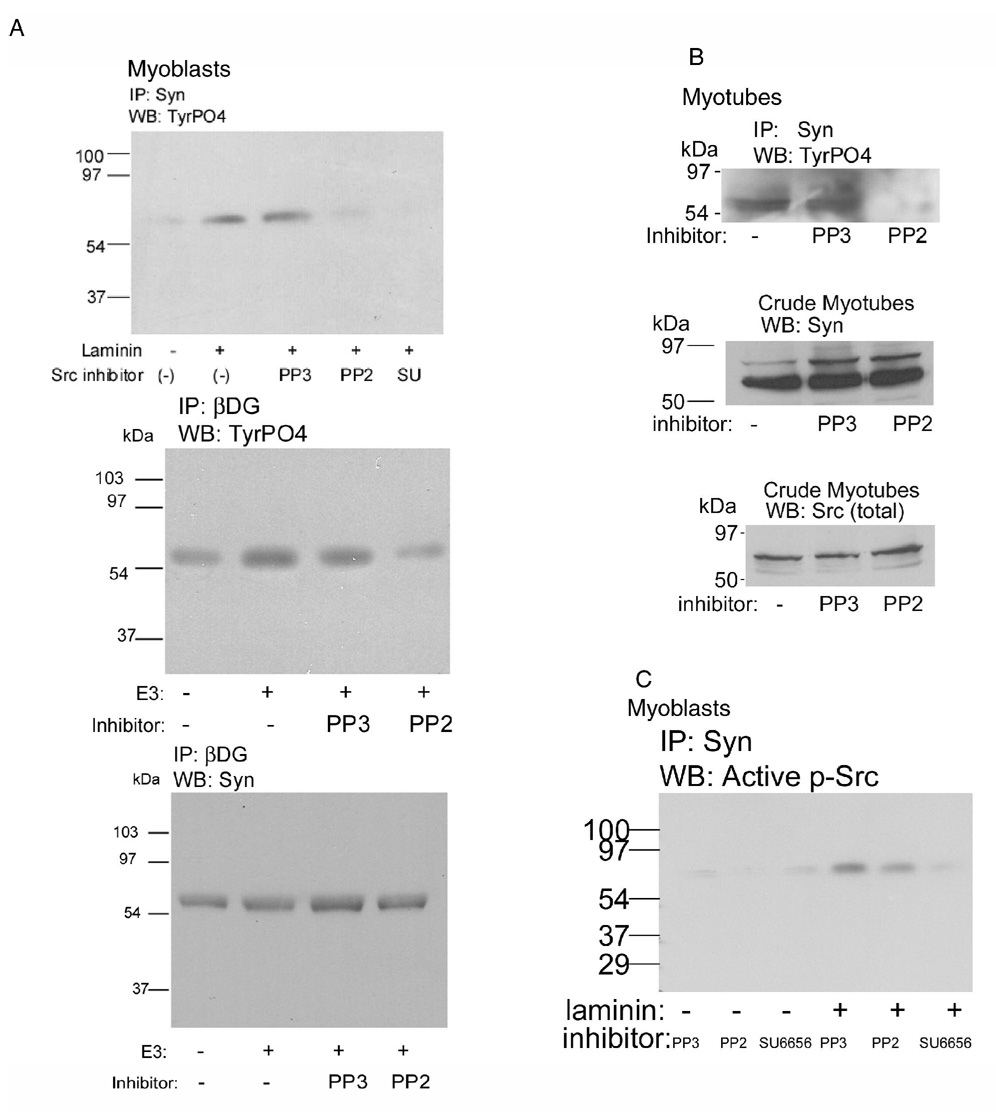

Src family kinase inhibitors also inhibit laminin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of syntrophin and Rac1 activation

Previously, we have shown that when laminin-binds to αDG, syntrophin is phosphorylated on tyrosine and this results in downstream activation of Rac1 by way of Grb2 and SOS1 (9). In Fig 1A, treatment of C2C12 myoblasts with two specific Src family kinase inhibitors, 10 µM PP2 and SU6656, inhibited laminin-binding-induced syntrophin phosphorylation on tyrosine whereas the inactive analog, PP3, had no effect (upper panel). This phosphorylated syntrophin is in a complex with βDG (lower two panels) showing that this is DGC syntrophin. Fig. 1B shows that in myotubes, syntrophin is also phosphorylated and this is inhibited by 2.5 µM PP2 (upper panel). The lower panels of Fig. 1B shows that inhibitor treatment is not affecting the total amounts of syntrophin or c-Src. Finally, Fig 1C shows that as laminin is added to trypsinized C2C12 myoblasts, c-Src is bound to syntrophin and becomes activated. c-Src activation occurs by its autophosphorylation on Tyr416, which is detected by this antibody. Ponceau Red staining, prior to the western blot, shows that each well contained equal loads of protein (Supplemental Data, Fig. S1). Thus, two different Src family kinase inhibitors, in cultured myotubes or myoblast prevent syntrophin phosphorylation while c-Src activation occurs in response to laminin binding. Furthermore, c-Src co-localizes along with syntrophin, in the DGC.

Figure 1. Inhibitors of Src family kinases inhibit laminin-induced signaling.

A, C2C12 myoblasts were cultured with 10 µM each of SU6656, PP2 or PP3 at 37 °C for 12 h. Microsomes were immunoprecipitated by syntrophin antibody and protein G-Sepharose in buffer K containing 1 mM CaCl2,1 mM GTPγS, 1 mM ATP and 1 % digitonin overnight at 4°C. After washing, SDS-PAGE buffer was added to each sample. Samples, after electrophoresis and electroblotting, were probed with antibody against the phosphotyrosine antibody (TyrPO4). Similarly, immunoprecipitation was also performed with a βDG antibody after treating myoblasts with E3 (1 µg/ml) and inhibitors (5 µM PP3 or 2.5 µM PP2) and either western blotted with the TyrPO4 antibody (middle panel) or the same blot was stripped and then western blotted with an antibody against syntrophin (Syn), B, experiments similar to those in panel A were also performed on C2C12 myotubes. In the upper panel, immunoprecipitation with the syntrophin antibody was performed after treating the myotubes with PP3 (5 µM) or PP2 (2.5 µM), and the blots probed with the TyrPO4 antibody. To show that the inhibitors were not affecting protein expression, in the middle and lower panels myotubes without immunoprecipitation were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with a syntrophin antibody, the blot was then stripped and re-probed with the Src antibody. C, C2C12 myoblasts were harvested by using trypsin-EDTA to deplete laminin and were treated with PP3 (5 µM) or PP2 (2.5 µM) for 3 h in PBS at 37 °C. Additional laminin (3 µg/100 µl) was added where shown and incubation was continued for one additional hour. Samples were washed with PBS twice. Cell lysate was made by adding RIPA buffer, pre-cleared with protein G-Sepharose, and the supernatant incubated with syntrophin antibody. The immune complexes were incubated with protein G-Sepharose. After washing, the bound protein was eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. After electrophoresis and electroblotting, the blots were detected with anti-Src (p-416) antibody and visualized by ECL.

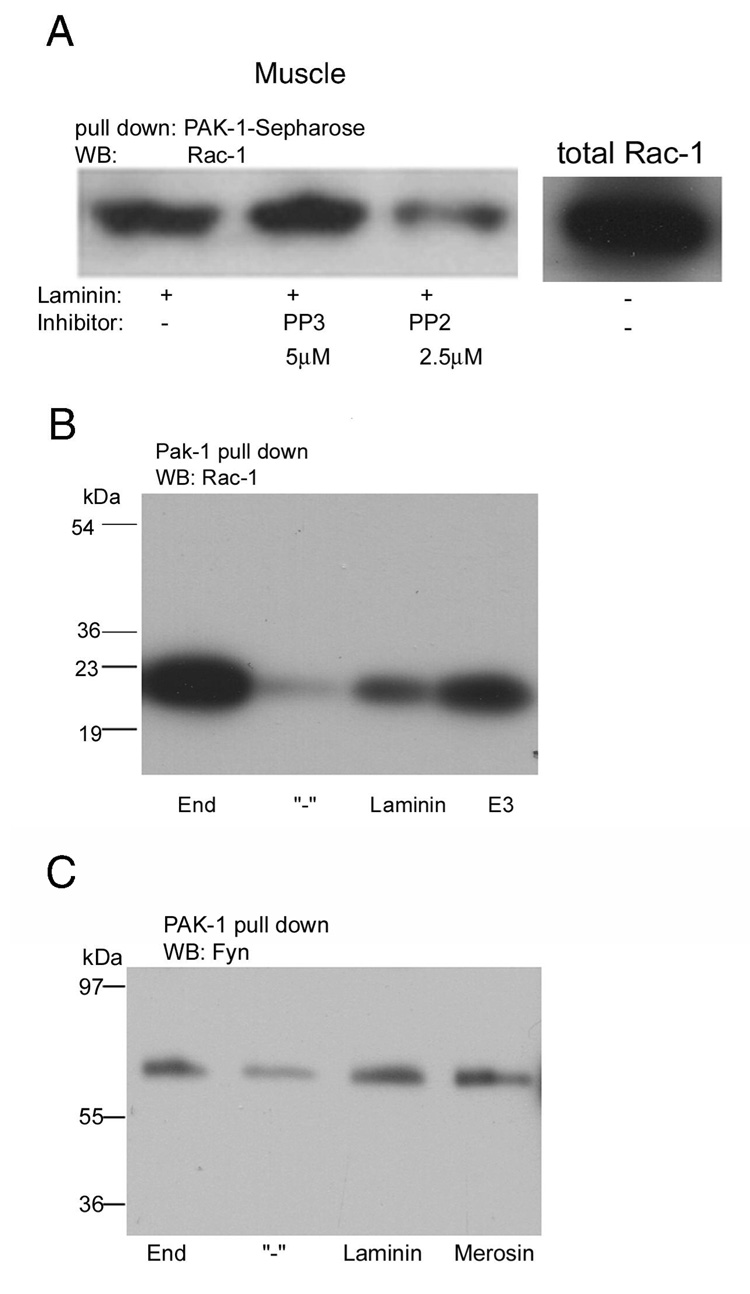

Laminin-binding and Src-family kinases also activate Rac1 in skeletal muscle

Previously, we had shown that laminin-binding or the binding of laminin E3 results in syntrophin phosporylation and Rac1 activation (GTP-binding) and initiates downstream signaling through c-jun N-terminal kinases. Furthermore, syntrophin binds Grb2 and Sos1 to cause Rac1 activation and syntrophin phosphorylation on tyrosine results in the Grb2 binding by its SH2 domain (3, 9). Fig 2A shows that even 2.5 µM PP2 was sufficient to inhibit the downstream activation of Rac1 in skeletal muscle microsomes whereas PP3 was ineffective, even at a higher concentration. Rac1 only binds to PAK1 when Rac1 is in the GTP-bound active form, and so the Rac1 bound by the PAK1-Sepharose in this experiment is activated Rac1. Only a portion of the total Rac1 is activated by laminin-binding. Thus, the activation of Rac1 requires syntrophin phosphorylation by a Src kinase family member. Fig. 2B shows that the activation of Rac1 occurs when even the small LG4–5 region of the laminin α-chain. Fig. 2C shows that c-Fyn is also associated with Rac1, and thus also with syntrophin, in a laminin-dependent manner. We conclude that a Src kinase family member, probably c-Src or c-Fyn, phosphorylates syntrophin in a laminin-dependent manner to result in Rac1 activation.

Figure 2. c-Fyn association and activation of Rac1 are laminin-dependent and PP2 inhibits.

A, Rabbit skeletal muscle membranes were treated with heparin-Sepharose for 1 h at 4 °C, and then the membranes were incubated with PP2 (2.5 µM) and PP3 (5 µM) at 4 °C for 3 h, laminin was added and incubation continued another hour in buffer K containing1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM GTPγS and 1 mM ATP, and mixed with PAK-1 bound to glutathione-Sepharose. Bound proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples, after electrophoresis and electroblotting, were probed with antibody against Rac1. The small panel to the right shows the same amount of microsomes not treated with PAK-1-Sepharose but also western blotted with Rac1 antibody in a parallel experiment to show the total amount of Rac1 present. B and C, Muscle microsomes were either treated with Sepharose to retain endogenous (End) laminin or extrated with heparin-Sepharose to deplete laminin (−) and laminin, E3, or merosin as indicated was added to depleted microsomes. Panels B show that relative to depleted microsomes, endogenous laminin, exogenous laminin or E3 result in greater activation of Rac1. Panel C shows the same basic experiment but probed with the c-Fyn antibody, showing a laminin-dependent association of c-Fyn with this protein complex, as was shown for c-Src in Fig. 1B.

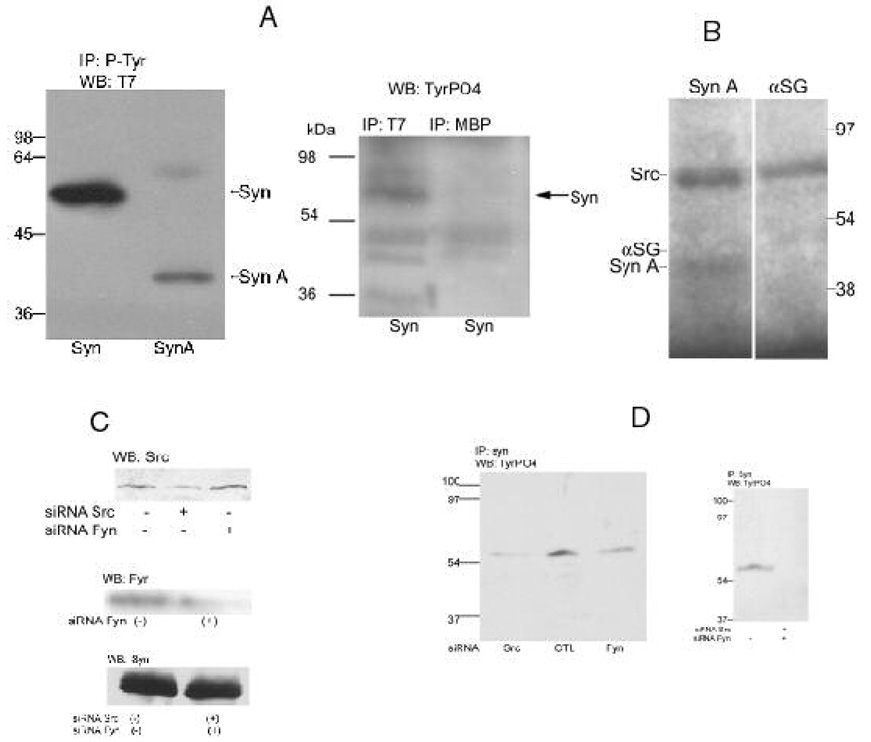

Muscle microsomes or purified c-Src and c-Fyn phosphorylate syntrophin fusion proteins on tyrosine and the inhibition by siRNAs

The results in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 were obtained with the endogenous proteins present in muscle microsomes or mouse muscle cultured cells. In Fig 3 A and B, we used bacterially expressed fusion proteins to confirm that syntrophin is indeed a substrate for c-Src. In Fig 3A, skeletal muscle microsomes were mixed with ATP and syntrophin or syntrophin A (mouse syntrophin protein sequences 2–274) fusion proteins and incubated to allow phosphorylation. Recovering the tyrosine phosphorylated proteins and staining with an antibody for the T7 antigen, present in these fusion proteins, shows that the microsomes contained a protein tyrosine kinase which utilizes syntrophin or the N-terminal half of syntrophin (syntrophin A) as substrate (left panel). The right panel shows that the result is specific for the T7 antigen and is not observed with a negative control antibody, in this case one against maltose-binding protein. In Fig. 3B, commercially available active c-Src was used to perform in vitro phosphorylation assays with γ-32P-ATP. Because c-Src autophosphorylates, it is also observed in these autoradiograms. An α-sarcoglycan fusion protein expressed from the same expression system was used as a negative control to eliminate the possibility that phosphorylation was of the fused sequences rather than syntrophin. Syntrophin A, rather than syntrophin, was used because it has a very different molecular weight than does c-Src and can be easily distinguished. Syntrophin A, but not the α-sarcoglycan fusion protein, is a substrate of c-Src. In Fig 3C and D, we used siRNA transfection in C2C12 cell to investigate the c-Src family kinases involved. Both c-Src and c-Fyn protein expression was reduced after transfection with their respective siRNA while neither affects syntrophin expression (Fig 3C). c-Src has been used to phosphorylate syntrophin proteins (Fig. 3B). In Fig. 3D, the phosphorylation of syntrophin also was significantly blocked by c-Src and c-Fyn siRNA but the effect is only partial, perhaps because neither siRNA completely blocks its corresponding kinase (left panel). However, the mixture of both c-Src and c-Fyn siRNA eliminates syntrophin phosphorylation (right panel). We conclude that either c-Src or c-Fyn can phosphorylate syntrophin. In other experiments (data not shown), c-Yes was not found to be associated with DGC syntrophin and was thus excluded.

Figure 3. Muscle microsomes or purified c-Src phosphorylates syntrophin fusion proteins while siRNA inhibits.

A, Bacterially expressed syntrophin (Syn) or syntrophin A (Syn A) His-Tag fusion proteins also have the T7 antigen at their N-terminus. The proteins (5 µg) were incubated with 100 µl of rabbit skeletal muscle microsomes in buffer K containing 1 mM CaCl2,1 mM GTPγS, 1 mM ATP and 1% digitonin for 1 h at 37°C. After pre-clearing with protein G-Sepharose, 3 µl of phosphotyrosine (p-Tyr, left panel) or T7 or maltose binding protein (MBP, an irrelevant control) antibody was added, incubated for 1 h on ice, and then with protein G-Sepharose for an additional hour. After washing, the proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. After electrophoresis and electroblotting, the fusion proteins were detected with the T7 (left panel) or TyrPO4 (right panel) antibodies and ECL. B, Syntrophin A or α-sarcoglycan (αSG) fusion proteins were phosphorylated in vitro using commercially available active c-Src under conditions described in Methods using 20,000 cpm/µl γ-32P-ATP. After incubation, the assay was mixed with an equal volume of twice concentrated SDS-PAGE sample buffer and, after electrophoresis, the gel was dried and placed on photographic film for autoradiography. The expected size for the fusion proteins are indicated by the arrows. C and D, C2C12 myotubes were transfected with siRNA against c-Src, Fyn or both c-Src and c-Fyn for 48h as described above in method. Proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (C). In D, Proteins were immunoprecipitated with syntrophin antibody. After SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and electroblotting, blots were probed with the antibodies against c-Src, c-Fyn and syntrophin (C) and TyrPO4 (D).

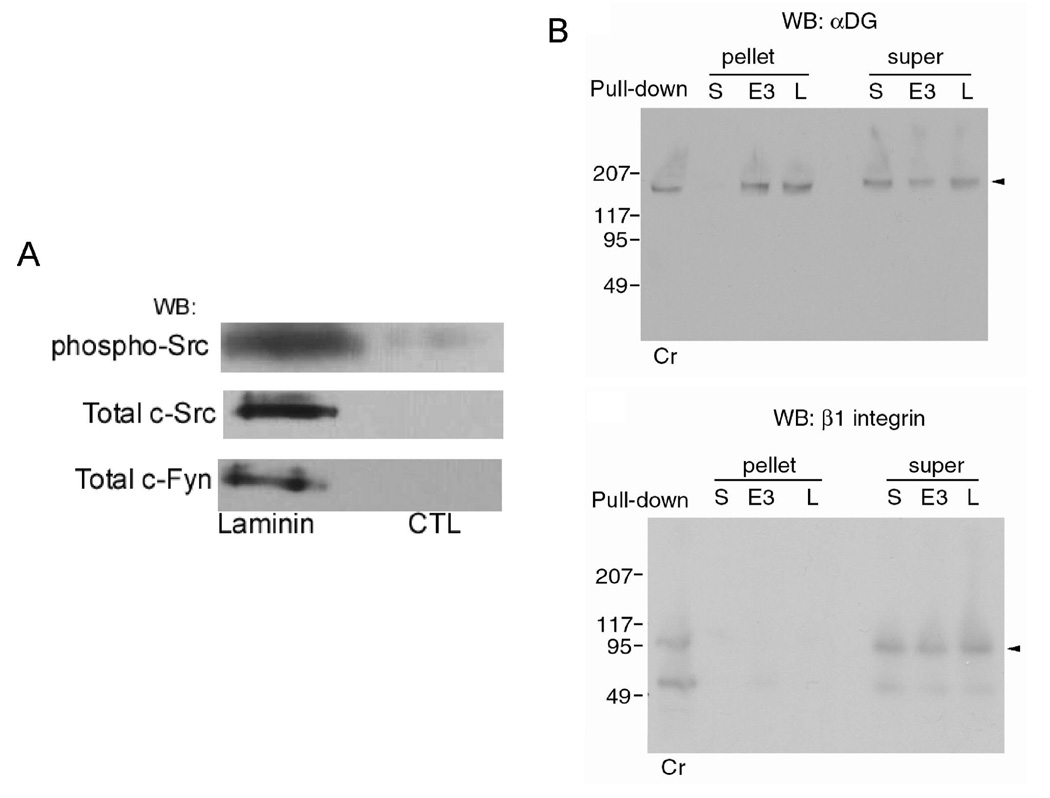

Laminin binds a complex containing both c-Src and c-Fyn

Fig. 4A shows that laminin-Sepharose binds a complex containing both c-Src and c-Fyn. In addition, an appreciable fraction of the c-Src in this complex was phosphorylated and thus active. While Sepharose did bind a small amount of these kinases under these conditions, clearly laminin-Sepharose bound a much greater amount. Previously, we have used blocking antibodies to show that laminin-binds to αDG to cause syntrophin phosphorylation and Rac1 activation (3, 9). Thus, laminin-Sepharose is most likely binding αDG and the DGC and both c-Src and c-Fyn are associated with this complex. The results in Fig. 4B further strengthen this argument. Under these same conditions, we found that laminin-Sepharose bound αDG and not to appreciable amount of integrins. All muscle integrins are β1-integrins and yet laminin-Sepharose does not bind detectable amounts of this subunit. We emphasize that this is likely true only under these conditions since it is clear from other investigations that integrins do bind laminin. However, under the conditions used here, laminin-Sepharose binds a complex of proteins that contains αDG, c-Src, and c-Fyn and previous figures show that this complex contains phosphorylated syntrophin and activated Rac1.

Figure 4. Laminin-Sepharose binds a complex containing Src family members and α-Dystroglycan.

A, Laminin-Sepharose (Laminin) and control-Sepharose (CTL) were incubated with rabbit skeletal muscle membranes in buffer K containing 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM GTPγS and 1 mM ATP. Digitonin was added to the microsomes, and incubation continued for 1 h. After washing, bound protein was eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples, after electrophoresis and electroblotting, were probed with antibodies against phospho-Src (Tyr416), c-Src and c-Fyn. B, Rabbit skeletal muscle microsomes were treated as describe in panel A except that either laminin (L)- or E3-Sepharose or control Sepharose (S) were used and the supernatants and pelleted resins were washed, eluted and subjected to SDS-PAGE and electroblotted. The blots were then probed with either the αDG antibody IIH6 or a commercially available antibody against integrin β1 subunit. The crude microsomes (Cr) are also included for comparison.

Contraction or stretching cause similar signaling

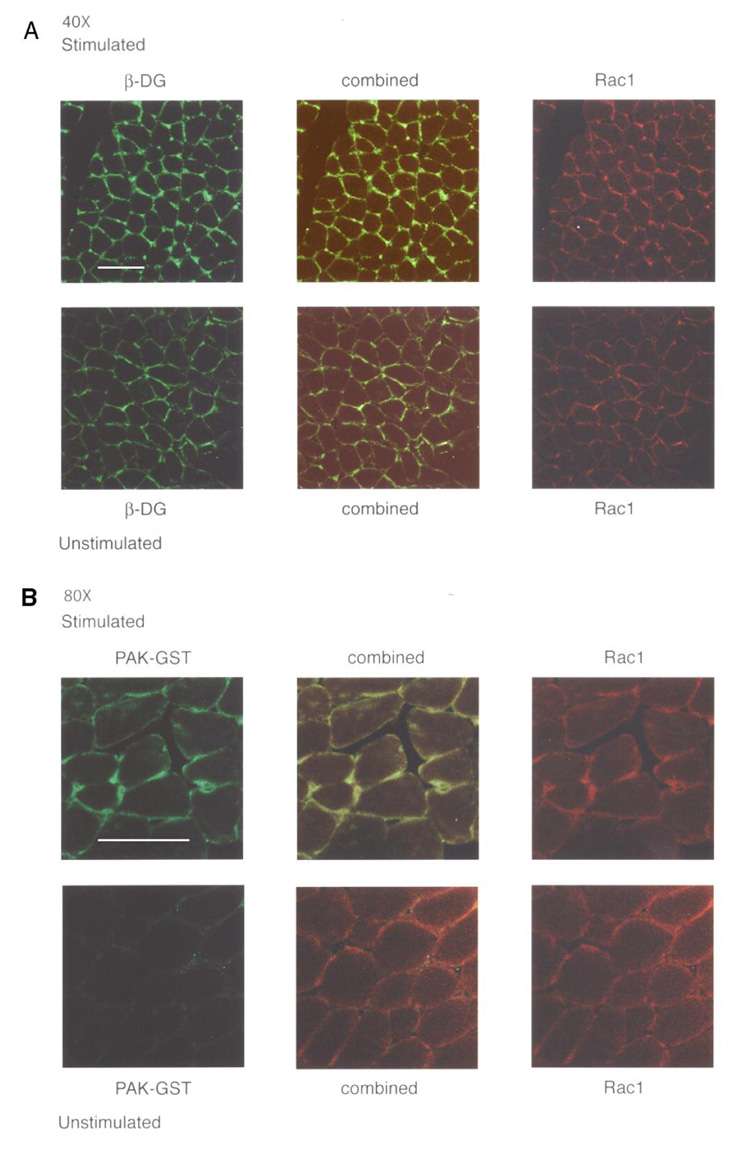

Because laminin is tightly bound to the exterior of the sarcolemma, it is unlikely that it is the presence or absence of laminin that regulates this signaling. However, contraction or stretching of muscle could stress the laminin-αDG linkage and this could provide an alternate way in which signaling could be initiated. This was tested in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6. In Fig. 5A, in both contracted (stimulated) and relaxed (unstimulated) muscle, Rac1 co-localized with DGC β-dystroglycan on the sarcolemma. This shows that a major portion of the Rac1 in muscle is co-localized with the DGC at this resolution. The images are not identical in that both β-dystroglycan and Rac1 stain less intensely in the uncontracted muscle. In Fig. 5B, the activation state of Rac1 was investigated by overlaying the sections with PAK1, which only binds active Rac1. Contraction of muscle leads to much higher activation of Rac1. Virtually identical results to those shown in Fig. 5 when muscle was contracted were also observed when muscle was stretched (supplemental data Fig. S2). Thus, it is stress on the laminin-DGC interaction which initiates signaling.

Figure 5. Contraction increases Rac1 association with the DGC and causes Rac1 activation.

β-dystroglycan and Rac1co-localize over the sarcolemma and Rac1 activation was increased by electric stimulation of the sciatic nerve. The gastrocnemius muscle in one rat hindlimb was contracted by electric stimulation of the sciatic nerve; the contralateral muscle was treated similarly except with no electrical stimulation. Panel A shows staining of the same section of rat muscle with βDG (stained green) and Rac1 (red) antibodies. The combined (merged) image shows yellow where the two co-localize. Panel B shows PAK-GST fusion protein (green) was greater in stimulated muscle compared with unstimulated muscle. Combined is the merged image showing yellow wherever PAK1 and Rac1 co-localize. The white bar shown is 50 µm.

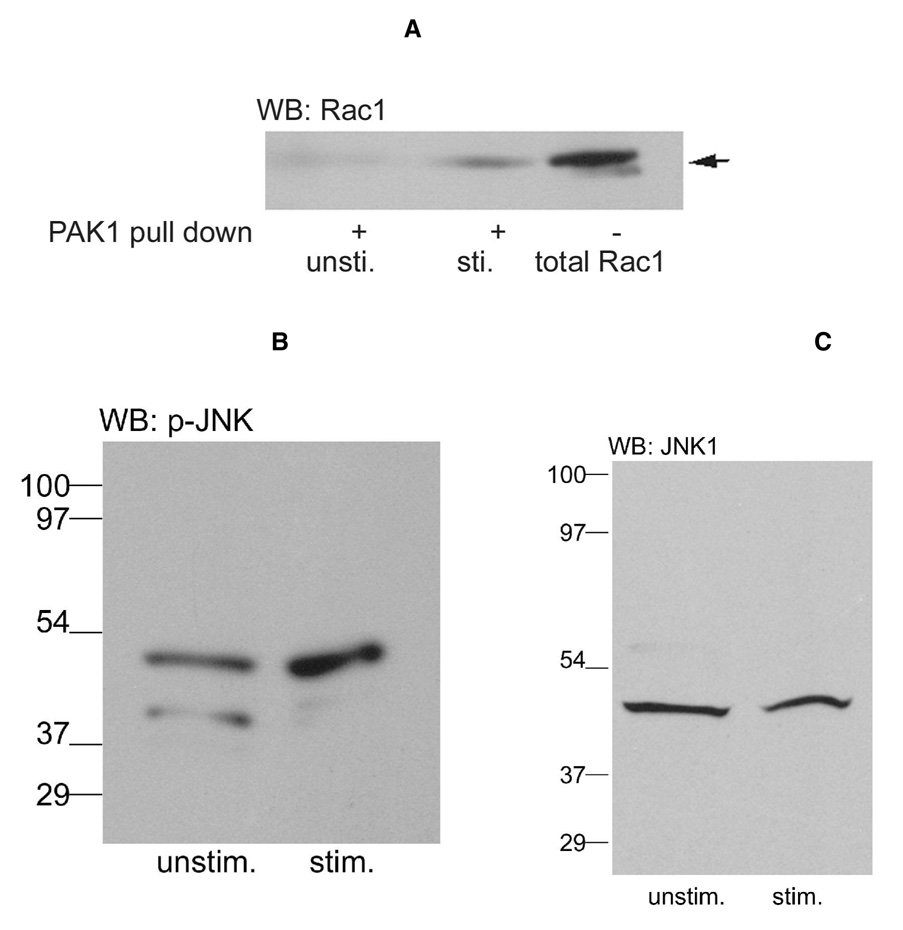

Figure 6. Contraction causes Rac1 and JNKp46 activation.

A, Samples were prepared as described in Fig. 5 from either contracted (stim.) or relaxed (unstim.) gastrocnemius muscle. Microsomes were prepared from each and incubated with PAK1-Sepharose in buffer K containing 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM GTPγS and 1 mM ATP. Digitonin was added to the microsomes, followed by incubation for 1h. Then, bound protein was eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples, after electrophoresis and electroblotting, were probed with antibodies against Rac1 (A). Because only activated (GTP-bound) Rac1 binds to PAK1, staining shows the amount of active Rac1. For comparison, the crude microsomes from stimulated muscle were also included to show the total amount of Rac1 present. B, the same microsomes as panel A was probed with antibodies against phosphorylated (active) JNK or C, with antibodies against total JNK1.

One shortcoming of the experiment in Fig. 5B is that PAK1 can bind to either active Rac1 or active cdc42, another p21 G-protein. That Rac1 is indeed activated is addressed in Fig. 6A. When muscle samples are contracted, the PAK1 bound protein is shown to stain with the Rac1 antibody and contracted muscle contained much more activated Rac1 than the relaxed muscle. Thus, at least two characteristics of laminin-dependent signaling, the association of Rac1 with the DGC and the activation of Rac1 are also stimulated by muscle contraction. In a previous report, it was shown that downstream of active Rac1 is the activation of JNKp46 (3). Thus, the same contracted and relaxed muscle samples were also investigated for this downstream signaling. Fig. 6B shows that muscle contraction also leads to activation of JNKp46 relative to the relaxed muscle. JNK is a family of three different kinases, JNK1, 2 and 3, each with multiple isoforms (19). In Fig. 6C, the blot shown in Fig. 6B was stripped and stained for JNK1. These data (Fig. 6C) show that the active JNKp46 is a JNK1 isoform. In addition, Fig. 6C also provides a loading control showing that it is the activation of JNK1 that changed while the total amount of JNK1 was similar in the two samples.

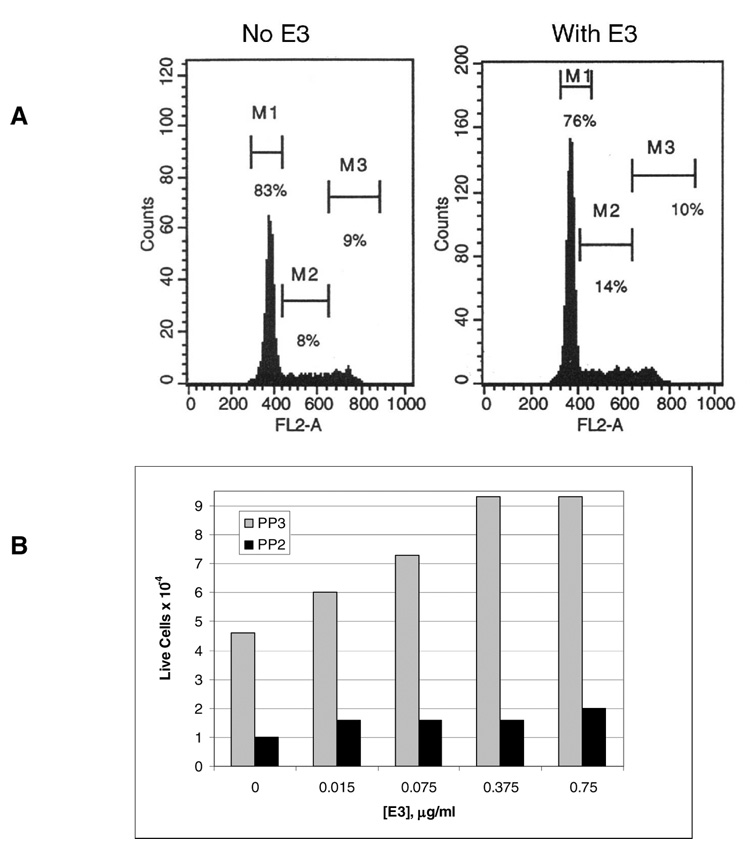

E3 causes the proliferation of the muscle cell line C2C12 myoblasts

C2C12 cells were incubated for 48 h with E3 (the LG4–5 region of the laminin α1 chain containing the αDG binding sequences). Propidium iodide was incorporated into the fixed cells to stain DNA and the cell cycle was analyzed by flow cytometry. For this experiment (Fig. 7A), over 40,000 cells were counted for each condition. The number of cells in G2-S phase (shown as the M2 bar in the figure) significantly increased from 8% to 14% with E3 addition. Thus, E3, or laminin (data not shown) causes cells to enter the synthesis phase and mitosis was initiated.

Figure 7. Laminin LG4–5 domains cause increased cell division in myoblasts and this is inhibited by a Src-family kinase inhibitor.

A, C2C12 myoblasts were incubated with E3 medium (containing 0.15 µg/ml E3) for 48 h. Propidium Iodide was incorporated after cells were fixed using 70% methanol. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. M1: G0/G1 phase, M2: S phase and M3: G2-M phase. B, C2C12 cells (1 × 104) were cultured for 24 h in 24-well plates in DMEM containing 10% FCS. With no additions, they grew to 4.2 ± 1 × 104 cells (n=6). When present PP3 or PP2 were added to 10 µM in the medium and the concentrations of E3 shown were added. The number of live cells, which exclude trypan blue, were counted. Each bar represents determination on triplicate cultures.

In Fig. 7B, the effect of PP2 Src family kinase inhibitor and E3 is shown. In other experiments, we determined that 10 µM PP3 had no effect on cell proliferation (data not shown) and that E3 increased cell proliferation (see Supplemental Data, Fig. S3). In the experiment shown, E3 also caused cell proliferation. Initially the plates were seeded with 1 × 104 cells and after 24 h of growth, this number increased to 4.3 × 104 cells, a number similar to the growth observed for PP3 in Fig. 7B. On the other hand, 10 µM PP2 inhibited cell proliferation in the presence or absence of E3. Increasing E3 concentration increased the cell number showing that E3 stimulated proliferation but clearly PP2, the Src family kinase inhibitor, prevented most of this cell proliferation. At the highest concentration of E3, the cell number increased approximately two-fold in the presence of PP2, while cell number increased more than 9-fold in the presence of inactive PP3.

In other experiments, we have observed a similar proliferative effect of laminin (data not shown) in agreement with others (2, 20). Thus, the proliferative effect of laminin results, at least in part, from the binding of a relatively small region of the laminin α-chain, the LG4–5 modules, which is also the region of laminin-1 that binds to αDG. This same E3 region of laminin also stimulates syntrophin tyrosine phosphorylation and Rac1 activation as well as other signaling through the DGC (3, 9, 10). One consequence of laminin- or E3-induced signaling is cell proliferation in myoblasts and this proliferative effect is inhibited by Src family kinase inhibition.

Discussion

The data presented clearly show that a c-Src family kinase phosphorylates syntrophin to initiate down-stream signaling through Rac1 and JNKp46. Laminin-binding and muscle tension also induce this signaling. c-Src phosphorylates syntrophin somewhere in its N-terminal half (present in Syntrophin A) and skeletal muscle microsomes contain this same or a similar activity. This region of syntrophin has four tyrosine residues, including two we had previously speculated could provide a site of phosphorylation (9). The precise residue(s) phosphorylated is a topic of current investigation.

Whether it is c-Src itself or another member of the c-Src family that causes the phosphorylation is unknown. This family of similar kinases has overlapping regulation, inhibition by PP2 and SU6656, and substrate specificity. At least one other member, c-Fyn, is also present in the laminin-bound complex (Fig. 4), is associated with active Rac1 (Fig. 2C) and decreasing it with its siRNA also lessens syntrophin phosphorylation (Fig. 3D). Thus, whether it is c-Src or c-Fyn which normally initiates this signaling is unclear.

Laminin-binding induces this signal cascade and here we show that muscle stimulation by either contraction or stretching induces the same signal cascade. This is what one would expect if laminin-binding to the DGC constitutes a mechanoreceptor, signaling muscle functional activity. Interestingly, a different laminin-receptor, the elastin-laminin receptor, has also been proposed as a mechanoreceptor in vascular smooth muscle (21). Interestingly, stretching of diaphram muscle activates Akt and that the mdx mouse has greater Akt activation than control animals (22). It has also been shown that laminin-binding to αDG results in Akt activation and decreased apoptosis (11). Thus, contraction or stretching initiate a variety of signaling pathways originating at the DGC. These pathways are also affected by mutations within this complex, and these affect muscle cell survival. Contraction or stretching in muscle inhibits atrophy and induces hypertrophy but how this is signaled is currently unknown. We propose that the laminin-DGC interaction participates in this signaling in muscle. The precise details of how this signaling affects muscle are only now beginning to emerge.

Another important aspect of this and our previous studies (3, 9, 10) is that this signaling pathway is functioning throughout muscle development, in myoblast, myotubes, and skeletal muscle. Myoblast express much lower amounts of DGC proteins (9, 23) and the DGC is much less well characterized in myoblast than it is in skeletal muscle and may be somewhat different. However, a complex containing αDG, βDG, and syntrophin has been shown to cause laminin-dependent signaling through Rac1, which ultimately leads to c-jun phosphorylation by JNK, and which also requires Src family kinase phosphorylation of syntrophin and is initiated by the same LG4–5 E3 region of laminin (Fig. 1–Fig. 3 and ref. (3, 9, 10)). Regardless of the exact composition of the DGC complex in myoblast, the complex that is there is functional in cell signaling and acts similar to the one in myotubes and skeletal muscle.

Muscle can increase mass by fusing myoblasts with the syncytial myotubes and increasing expression from existing myonuclei. Here we show that laminin E3 induces proliferation of myoblasts. Because c-Src family kinase inhibitors prevent this proliferation, myoblast proliferation presumably also requires member(s) of this kinase family. In myoblasts, c-Src inhibitors also inhibit syntrophin phosphorylation (Fig. 1A), and most aspects or the syntrophin-Rac1-JNKp46 pathway have also been shown to occur in myoblasts (3, 9, 10). Thus, laminin-binding initiates this signaling throughout the life of the muscle cell and may, by increasing myoblast proliferation, provide a means for hypertrophy in muscle. Because this signaling is also induced by contraction or stretching, either the laminin-αDG-syntrophin-Rac1-JNKp46 pathway we have studied here or the laminin-αDG-PI3K-Akt pathway described by others (11, 22) may be different functional aspects of the same mechanoreceptor. Defects in this mechanoreceptor may help explain the severe pathologies of muscular dystrophy when the laminin-DGC mechanoreceptor is altered by genetic mutation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Magda Loranc for excellent technical assistance, Dr. Donald Gullberg for his E3 expressing cells, and Drs. Kevin Campbell and Tamara Petrucci for their dystroglycan antibodies.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant AR051440) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (grant 3789).

Abbreviations Used: DGC, dystrophin glycoprotein complex; JNKp46, the 46,000 molecular mass isoform of c-Jun N-terminal Kinase; LG, laminin globular domains; E3, an expressed protein containing only α1-laminin domains LG4–5; αDG , α-dystroglycan; βDG , β-dystroglycan; αSG, α-sarcoglycan; Syn, syntrophin; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; GST, glutathione S-transferase; PAK1, p21-activated kinase;

References

- 1.Hoffman EP, Brown RH, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gullberg D, Tiger C-F, Velling T. Laminins during muscle development and in muscular dystrophies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1999;56:442–460. doi: 10.1007/PL00000616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oak SA, Zhou YW, Jarrett HW. Skeletal Muscle Signaling Pathway Through the Dystrophin Glycoprotein Complex and Rac1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39287–39295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tisi D, Talts JF, Timpl R, Hohenester E. Structure of the C-terminal laminin G-like domain pair of the laminin alpha2 chain harbouring binding sites for alpha-dystroglycan and heparin. EMBO J. 2000;19:1432–1440. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smirnov SP, McDearmon EL, Li S, Ervasti JM, Tryggvason K, Yurchenco PD. Contributions of the LG modules and furin processing to laminin-2 functions. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:18928–18937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201880200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu H, Talts JF. Beta1 integrin and alpha-dystroglycan binding sites are localized to different laminin-G-domain-like (LG) modules within the laminin alpha5 chain G domain. Biochem. J. 2003;371:289–299. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durbeej M, Talts JF, Henry MD, Yurchenco PD, Campbell KP, Ekblom P. Dystroglycan binding to laminin alpha1LG4 module influences epithelial morphogenesis of salivary gland and lung in vitro. Differentiation. 2001;69:121–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.690206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiger CF, Champliaud MF, Pedrosa-Domellof F, Thornell LE, Ekblom P, Gullberg D. Presence of laminin alpha5 chain and lack of laminin alpha1 chain during human muscle development and in muscular dystrophies. J Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28590–28595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou YW, Thomason DB, Gullberg D, Jarrett HW. Binding of laminin alpha1-chain LG4–5 domain to alpha-dystroglycan causes tyrosine phosphorylation of syntrophin to initiate Rac1 signaling. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2042–2052. doi: 10.1021/bi0519957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou YW, Oak SA, Senogles SE, Jarrett HW. Laminin-α1 Globular Domains Three and Four Induce Heterotrimeric G-Protein binding to α-Syntrophin's PDZ Domain. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C377–C388. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00279.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langenbach KJ, Rando TA. Inhibition of dystroglycan binding to laminin disrupts the PI3K/AKT pathway and survival signaling in muscle cells. Muscle & Nerve. 2002;26:644–653. doi: 10.1002/mus.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas AM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDearmon EL, Burwell AL, Combs AC, Renley BA, Sdano MT, Ervasti JM. Differential heparin sensitivity of alpha-dystroglycan binding to laminins expressed in normal and dy/dy mouse skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:24139–24144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newbell BJ, Anderson JT, Jarrett HW. Ca2+-Calmodulin Binding to Mouse a1 Syntrophin: Syntrophin is also a Ca2+-binding protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1295–1305. doi: 10.1021/bi962452n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dowler S, Montalvo L, Cantrell D, Morrice N, Alessi DR. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent phosphorylation of the dual adaptor for phosphotyrosine and 3-phosphoinositides by the Src family of tyrosine kinase. Biochem. J. 2000;349:605–610. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chockalingam PS, Cholera R, Oak SA, Zheng Y, Jarrett HW, Thomason DB. Dystrophin-glycoprotein Complex and Ras and Rho GTPase signaling are altered in muscle atrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;283:500–511. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00529.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis RJ. Signal Transduction by the JNK Group of MAP Kinases. Cell. 2000;103:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ocalan M, Goodman SL, Kuhl U, Hauschka SD, von der Mark K. Laminin alters cell shape and stimulates motility and proliferation of murine skeletal myoblasts. Dev. Biol. 1988;125:158–167. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spofford CM, Chilian WM. The elastin-laminin receptor functions as a mechanotransducer in vascular smooth muscle. Am.J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001;280:H1354–H1360. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dogra C, Changotra H, Wergedal JE, Kumar A. Regulation of phosphatidyl 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and Nuclear Factor-Kappa B signaling pathways in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle in response to mechanical stretch. J. Cellular Physiol. 2006;208:575–585. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osses N, Brandan E. ECM is required for skeletal muscle differentiation independently of muscle regulatory factor expression. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:383–394. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00322.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.