Abstract

Study Objectives:

To explore age differences in the relationship between sleep duration and mortality by conducting analyses stratified by age. Both short and long sleep durations have been found to be associated with mortality. Short sleep duration is associated with negative health outcomes, but there is little evidence that long sleep duration has adverse health effects. No epidemiologic studies have published multivariate analyses stratified by age, even though life expectancy is 75 years and the majority of deaths occur in the elderly.

Design:

Multivariate longitudinal analyses of the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey using Cox proportional hazards models.

Setting:

Probability sample (n = 9789) of the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the United States between 1982 and 1992.

Participants:

Subjects aged 32 to 86 years.

Measurements and Results:

In multivariate analyses controlling for many covariates, no relationship was found in middle-aged subjects between short sleep of 5 hours or less and mortality (hazards ratio [HR] = 0.67, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.43–1.05) or long sleep of 9 hours or more and mortality (HR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.66–1.65). A U-shaped relationship was found only in elderly subjects, with both short sleep duration (HR = 1.27, 95% CI 1.06–1.53) and long sleep duration (HR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.15–1.60) having significantly higher HRs.

Conclusions:

The relationship between sleep duration and mortality is largely influenced by deaths in elderly subjects and by the measurement of sleep durations closely before death. Long sleep duration is unlikely to contribute toward mortality but, rather, is a consequence of medical conditions and age-related sleep changes.

Citation:

Gangwisch JE; Heymsfield SB; Boden-Albala B; Buijs RM; Kreier F; Opler MG; Pickering TG; Rundle AG; Zammit GK; Malaspina D. Sleep duration associated with mortality in elderly, but not middle-aged, adults in a large US sample. SLEEP 2008;31(8):1087-1096.

Keywords: Sleep, mortality, epidemiology

A U-SHAPED RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SLEEP DURATION AND MORTALITY, WITH BOTH SHORT AND LONG SLEEP DURATIONS BEING ASSOCIATED WITH higher mortality, has been called a ubiquitous finding in epidemiologic studies.1 These results are not surprising for short sleep duration, since short sleep duration has been linked to diabetes,2–5 obesity,6–9 and hypertension10–13 in both experimental and epidemiologic studies. The association between short sleep duration and morbidity therefore provides plausible arguments for a causal connection between short sleep and mortality.

The association between long sleep duration and increased mortality consistently found in epidemiologic studies has posed a conundrum, since there is little evidence to suggest that sleeping for longer than 8 hours has adverse health effects. No published laboratory or epidemiologic studies have demonstrated a possible mechanism identifying long sleep as a cause of either morbidity or mortality.14 Despite this, the association between long sleep and mortality has been viewed as justification by some investigators to recommend sleep restriction to decrease mortality risk.1 The popular press also has used these findings to warn the public against “oversleeping.” 14,15 There are a number of problems with using these findings to make the inference that sleeping more than 8 hours is detrimental to health. First, no published epidemiologic studies on the association between sleep duration and mortality have reported multivariate analyses stratified by age even though the majority of the deaths in these studies presumably occurred among the elderly, since the average life expectancy in the developed world is about 75 years. Second, these studies have relatively brief follow-up durations of typically about 10 years, so, in those who died over the follow-up periods, sleep durations were measured rather shortly before these subjects died. The elderly subjects' reported sleep durations shortly before they died were unlikely to have been reflective of their sleep durations over the course of their lifetimes when they could have been developing chronic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension that eventually contributed toward their deaths. Third, as age increases, the risk of death, a universal outcome, obviously increases. Advanced age is also associated with changes in sleep architecture with increased difficulties in sleep initiation and maintenance.16 Age has been shown to act as an effect modifier in the relationship between sleep duration and obesity8 and between sleep duration and hypertension incidence.12 Age could therefore also act as an effect modifier in the relationship between sleep length and mortality, and multivariate analyses stratified by age could help shed light on the question of why long sleep duration might be associated with increased mortality.

In this study, we explored the relationship between sleep duration and mortality over an 8- to 10-year follow-up period between 1982 and 1992 among subjects who participated in the Epidemiologic Follow-up Studies of the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I).17–20 We hypothesized that there would be a U-shaped relationship between length of sleep and mortality in the total sample of subjects. We theorized that diabetes, body weight, and hypertension, potent risk factors for mortality, act as partial mediators of this relationship. We also hypothesized that the relationship between sleep duration and mortality would differ between middle-aged and elderly subjects in analyses stratified by age.

METHODS

Participants

Subjects for this study were participants in the 1982–1984, 1986, 1987, and 1992 Epidemiologic Follow-up Studies of the NHANES I. The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study is a longitudinal study of adults originally examined and interviewed in 1971–1975 as part of the NHANES I. The primary purpose of the follow-up study is to investigate the longitudinal effects of clinical, environmental, and behavioral factors on health conditions. The 1982–1984 wave of data collection followed all medically examined respondents who had been 25 to 74 years of age in 1971–1975 (n = 14,407). Eighty-five percent of all eligible subjects were successfully recontacted (n = 12,220). The measures of self-reported sleep duration were taken from the 1982–1984 survey when the following question was asked: “How many hours of sleep do you usually get a night (or when you usually sleep)?” Data from individuals who were deceased (n = 1697) or who did not answer the sleep-duration question (n = 734) were excluded from the analyses, yielding a final sample size of 9789 subjects. The 1986 wave focused on subjects who had been 55 to 74 years of age at their baseline examinations in 1971–1975, whereas the 1987 and 1992 waves followed all medically examined respondents who had been 25 to 74 years of age in 1971–1975. Mortality was determined over an 8- to 10-year follow-up period from death certificates and proxy interviews at the 1986, 1987, and 1992 Follow-up Studies. This study involved analyses of a publicly available dataset that did not include identifying information and therefore met federal guidelines for exemption from review by an institutional review board.

Measures

The dependent variable used in this study was death at some time over the 8- to 10-year follow-up period, as determined from death certificates and proxy interviews. The independent variable was the subject's self-reported average sleep duration in hours. The sleep-duration question was asked only at baseline, the time of the 1982–1984 wave, and was not asked again at the times of the 1986, 1987, and 1992 follow-ups. We categorized the sleep-duration variable, as opposed to retaining it as a continuous variable, because each additional hour of sleep was not associated with the same change in the dependent variable.

We included, in our multivariate models, variables that were associated with both sleep duration and mortality, variables that therefore could have acted as either confounders or mediators in the relationship between sleep duration and mortality. Covariates were drawn from the 1982–1984 wave, which included questions on age (continuous variable), history of diabetes (yes, no), body weight (body mass index = kg/m2, with the following definitions: underweight < 18.5 kg/m2, lean ≥ 18.5 kg/m2and < 25 kg/m2, overweight ≥ 25 kg/m2 and < 30 kg/m2, obese ≥ 30 kg/m2 and < 40 kg/m2, or morbidly obese ≥ 40 kg/m2), history of hypertension (yes, no), history of cancer (yes, no), smoking (0, 1–5, 6–10, 11–20, or > 20 cigarettes per day), depression (yes, no), sex, education (high school graduate or < high school graduate), living alone (alone or with others), low income (< $10,000 or ≥ $10,000), daytime sleepiness (never/rarely, sometimes, often, or almost always), nighttime awakening (never/rarely, sometimes, often, or almost always), ethnicity (Caucasian, African-American, or other), and sleeping pill use (continuous variable—average per day). To measure the presence of depressive symptoms, we used the standard cutoff score of 16 out of a total possible score of 60 on the 20-question Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).21 We measured the subject's level of physical activity by adding the scores from 2 questions that asked the subjects to estimate how much physical activity they obtained in recreational and nonrecreational activities. The first question asked: “In things you do for recreation, for example, sports, hiking, dancing, etc., do you get much exercise, moderate exercise, or little/no exercise?” The second question asked: “In your usual day, aside from recreation, are you physically very active, moderately active, or quite inactive?” We assigned a score of 3 if they got much exercise or were very active, 2 if they got moderate exercise or were moderately active, and 1 if they got little or no exercise or were inactive. After the scores from the 2 questions were added together, the total physical activity scores ranged from 2 to 6, with increasing scores representing increasing levels of physical activity. To compute body mass index, we used heights from medical examinations conducted between 1971 and 1975 and actual body weights measured with scales at the 1982–1984 interviews. There were 198 subjects, representing 2% of the sample, who had missing values on measured body weight. For subjects with missing values on measured body weight, we substituted their self-reported body weight for measured body weight. The measured and self-reported body weights obtained in 1982–1984 for the entire sample had a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.975, indicating a reasonable level of accuracy for the self-reported weights. Missing values for other covariates, which for all covariates represented less than 1% of the total sample size, were imputed using mean and mode substitution.

Statistical Analyses

After performing preliminary univariate and bivariate analyses, we used Cox proportional hazards models to examine the effect of sleep duration upon the risk for death over the 8- to 10-year follow-up period. The time duration to death was determined from the baseline date to the reported date of death. We chose 7 hours as the reference category for 3 reasons. First, 7 hours of sleep has consistently been shown to have the lowest mortality risk.1 Second, the mean sleep duration is 7 hours in this sample and in adults in the US.22 Third, the choice of this category eased interpretation of the hazards ratios (HR), since subjects who reported getting 7 hours of sleep had the lowest mortality. Covariates in the first adjusted multivariate model (Model 2) included age, physical activity, smoking, depression, sex, education, living alone, low income, daytime sleepiness, nighttime awakening, ethnicity, and sleeping pill use. Covariates in the second adjusted model (Model 3) included the variables in Model 2 plus body weight, diabetes, and hypertension to test whether these variables acted as partial mediators of the relationship between sleep duration and mortality. The final model (Model 4) included the variables in Model 3 plus general health and cancer to test whether these variables acted as partial mediators. The significance of individual coefficients in the Cox proportional hazards models were determined by the 95% confidence limits for HR.

To test whether there would be differences between middle-aged and older adults in the relationship between sleep duration and mortality, we divided the sample into 2 age groups with subjects who, at the time of the 1982–1984 wave, were between the ages of 32 and 59 years in one group and subjects who where between the ages of 60 and 86 years in another group. After subjects who had died before the 1982–1984 wave or who did not answer the sleep-duration question were excluded, there were 5806 subjects between the ages of 32 and 59 years and 3983 subjects between the ages of 60 and 86 years for the analyses. We also conducted analyses stratified by sex. To investigate whether age and sex acted as effect modifiers in the relationship between sleep duration and mortality, we included interaction terms between age (ages 32–59 vs 60–86) and sleep duration (≤ 5 hours vs 7, and ≥ 9 hours vs 7) and between sex and sleep duration in regression models using the GENMOD procedure with SAS Software.23 Due to the U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and mortality, we conducted separate analyses for short and long sleep durations.

The NHANES I included weights to account for the complex sampling design and to allow approximations of the US population. We conducted both unweighted analyses using SAS software and weighted analyses using SUDAAN24 software. We chose to present only the unweighted results for 4 reasons. First, the weighted results were generally consistent with minimal effects of the complex survey design on the main conclusions derived from the unweighted estimates. Second, our objective was not to provide national estimates, but to look at the relationship between sleep duration and mortality. Third, our study's baseline measures were taken from the 1982–1984 Follow-up to the NHANES I, so the weights created for baseline measures taken from the 1971–1975 NHANES I did not account for subjects who were lost to follow-up between the 2 waves. Fourth, there have been differences of opinion regarding the appropriateness of using the sample weights with the NHANES.25

RESULTS

There were 1877 deaths over the 8- to 10-year follow-up period, representing 19% of the sample. The average time duration from baseline to death was 4.9 years (SD = 2.7) and the average age at death was 76.6 years (SD = 11.0). The majority (86%) of the deaths (n = 1604) occurred among older subjects who were between the ages of 60 and 86 years at baseline. More men (n = 947) than women (n = 930) died over the follow-up period, despite the fact that women (n = 6152) outnumbered men (n = 3637) in the sample. Among subjects who died over the follow-up period, the longest average length of time until death (5.1 years) was for subjects with 7-hour sleep durations, whereas the shortest average lengths of time until death were for subjects with short (4.8 years) and long (4.8 years) sleep durations, but the differences between these sleep-duration categories were not statistically significant. Table 1 shows the causes of death by age group. The 2 leading causes of death in middle-aged and elderly subjects were major cardiovascular diseases and cancers. These 2 disease categories accounted for 75% of the deaths in elderly subjects and 70% in middle-aged subjects. More middle-aged subjects died from diabetes, liver disease, and external causes, whereas more elderly subjects died from pneumonia and influenza.

Table 1.

Cause of death by age category

| Cause of death (no.) | Subject age, ya |

X2 (P value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 32–59 | 60–86 | ||

| Tuberculosis (3) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) | 106.40 |

| (< 0.0001) | |||

| Residual of infectious and parasitic disease (26) | 5 (1.8) | 21 (1.3) | |

| Malignant neoplasms/cancers (475) | 97 (35.5) | 378 (23.6) | |

| Diabetes mellitus (45) | 11 (4.0) | 34 (2.1) | |

| Major cardiovascular diseases (917) | 95 (34.8) | 822 (51.3) | |

| Pneumonia and influenza (69) | 3 (1.1) | 66 (4.1) | |

| COPD and allied conditions (83) | 7 (2.6) | 76 (4.7) | |

| Ulcer of stomach and duodenum (7) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (0.4) | |

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis (20) | 13 (4.8) | 7 (0.4) | |

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, nephrosis (19) | 2 (0.7) | 17 (1.1) | |

| Congenital anomalies (1) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| All other diseases (164) | 20 (7.3) | 144 (9.0) | |

| External causesb (48) | 16 (5.9) | 32 (2.0) | |

Data are provided as number (% of total).

External causes include accidents, suicide, and homicide.

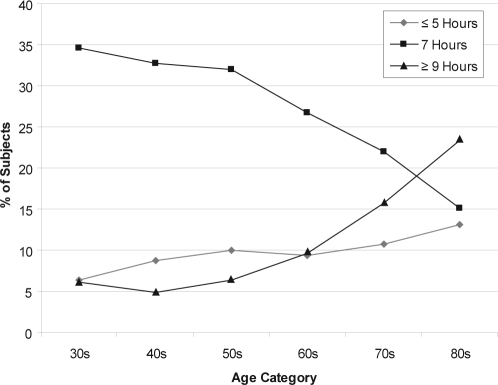

Figure 1 shows the percentages of subjects in each 10-year age group who reported various sleep durations. As the age of the subjects increased, the percentages of subjects who reported 7-hour sleep durations decreased, the percentages who reported long sleep durations ( ≥ 9 hours) increased, and the percentages who reported short sleep durations (≤ 5 hours) had an increasing trend. The percentages who reported 8-hour and 6-our sleep durations (not shown in table) stayed relatively stable.

Figure 1.

Percentages of subjects in each 10-year age group who reported various sleep durations

Results for the bivariate analyses are shown in Tables 2, 3, and 4. In Table 2 male sex, older age, less than a high-school education, low income, lower physical activity, depression, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, living alone, African American ethnicity, increased daytime sleepiness, increased nighttime awakening, sleeping pill use, and poorer general health were all associated with increased mortality over the follow-up period. Increased smoking and higher body mass index were paradoxically associated with decreased mortality. Subjects who smoked a pack or more of cigarettes per day were less likely to die over the follow-up period than were those who did not smoke at all or who smoked less. Subjects who were morbidly obese and obese were the first and second least likely to die over the follow-up period, respectively, compared with the subjects in the other weight categories. Table 3 shows the baseline characteristics of the entire sample according to their sleep-duration categories. Sleep durations of both 5 hours or less and 9 hours or more were associated with older age, lower physical activity, higher body mass index, poorer general health, increased daytime sleepiness, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, depression, less than a high-school education, non-Caucasian ethnicity, living alone, low income, and higher use of sleeping pills. Nighttime awakening was associated with shorter sleep durations. Table 4 shows significant differences between sleep-duration categories and mortality over the follow-up period for the total sample of subjects between the ages of 32 and 86 years. The relationships differed though between the middle-aged and older subjects; the older subjects had a more highly statistically significant association between mortality and sleep duration, with higher percentages of deaths over the follow-up period among subjects who reported both short (≤ 5 hours) and long ( ≥ 9 hours) sleep durations.

Table 2.

Relationship Between Risk Factors for Mortality and Baseline Characteristics by Survival Over Follow-Up Period

| Baseline characteristic | Dead | Alive | X2 (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Women | 930 (15) | 5222 (85) | 175.90 (P < 0.0001) |

| Men | 947 (26) | 2690 (74) | |

| Age, y | |||

| 32–39 | 20 (1) | 1366 (99) | 2668.88 (P < 0.0001) |

| 40–49 | 79 (3) | 2263 (97) | |

| 50–59 | 174 (7) | 1904 (93) | |

| 60–69 | 336 (18) | 1249 (81) | |

| 70–79 | 812 (43) | 883 (57) | |

| 80–86 | 456 (60) | 247 (40) | |

| High-school graduate | |||

| Yes | 737 (12) | 5279 (88) | 482.82 (P < 0.0001) |

| No | 1140 (30) | 2633 (70) | |

| Income, $ | |||

| ≥ 10,000 | 967 (14) | 6132 (86) | 513.99 (P < 0.0001) |

| < 10,000 | 910 (34) | 1780 (66) | |

| Physical activitya | |||

| 6 | 118 (13) | 806 (87) | 514.28 (P < 0.0001) |

| 5 | 180 (11) | 1449 (89) | |

| 4 | 662 (17) | 3346 (83) | |

| 3 | 398 (20) | 1578 (80) | |

| 2 | 519 (40) | 733 (60) | |

| Cigarettes smoked/day | |||

| 0 | 1430 (20) | 5649 (80) | 38.55 (P < 0.0001) |

| 1 | 42 (18) | 194 (82) | |

| 5 | 51 (22) | 178 (78) | |

| 10 | 131 (21) | 493 (79) | |

| 20 | 223 (14) | 1398 (86) | |

| Depression | |||

| No | 1430 (18) | 6569 (82) | 47.51 (P < 0.0001) |

| Yes | 447 (25) | 1343 (75) | |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 1578 (17) | 7502 (83) | 260.85 (P < 0.0001) |

| Yes | 299 (42) | 410 (58) | |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight | 103 (44) | 133 (56) | 97.45 (P < 0.0001) |

| Normal weight | 791 (19) | 3329 (81) | |

| Overweight | 647 (19) | 2841 (81) | |

| Obese | 307 (18) | 1442 (82) | |

| Morbidly obese | 29 (15) | 167 (85) | |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 388 (10) | 3665 (90) | 411.44 (P < 0.0001) |

| Yes | 1489 (26) | 4247 (74) | |

| Cancer | |||

| No | 1556 (17) | 7358 (83) | 190.12 (P < 0.0001) |

| Yes | 321 (37) | 554 (63) | |

| Living arrangements | |||

| With others | 1302 (16) | 6921 (84) | 370.20 (P < 0.0001) |

| Alone | 575 (37) | 991 (63) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 1578 (19) | 6791 (81) | 11.10 (P = 0.0039) |

| African American | 273 (22) | 959 (78) | |

| Other | 26 (14) | 162 (86) | |

| Daytime sleepiness | |||

| Never | 505 (16) | 2677 (84) | 476.08 (P < 0.0001) |

| Rarely | 313 (12) | 2227 (88) | |

| Sometimes | 422 (18) | 1910 (82) | |

| Often | 273 (31) | 594 (69) | |

| Almost always | 364 (42) | 504 (58) | |

| Nighttime awakeninga | |||

| Never | 449 (20) | 1843 (80) | 118.80 (P < 0.0001) |

| Rarely | 378 (14) | 2317 (86) | |

| Sometimes | 472 (18) | 2098 (82) | |

| Often | 294 (24) | 931 (76) | |

| Almost always | 284 (28) | 723 (72) | |

| Sleeping pill use | |||

| No | 1656 (18) | 7353 (82) | 45.87 (P < 0.0001) |

| Yes | 221 (28) | 559 (72) | |

| General healtha | |||

| Excellent | 162 (8) | 1876 (92) | 821.37 (P < 0.0001) |

| Very Good | 319 (12) | 2313 (88) | |

| Good | 546 (19) | 2321 (81) | |

| Fair | 533 (33) | 1067 (67) | |

| Poor | 317 (49) | 335 (51) |

Data are presented as number (%).

Activity level is rated from 6, high, to 2, low. Depression yes and no correspond with a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale of ≥ 16 and < 16, respectively.

Table 4.

Relationship between sleep duration at baseline and mortality over follow-up period

| Amount of sleep, h (no.) | Status at follow-up |

X2 (P value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dead | Alive | ||

| Total sample (9789) | |||

| ≤ 5 (912) | 233 (12) | 679 (9) | 278.03 (P < .0001) |

| 6 (1949) | 298 (16) | 1651 (21) | |

| 7 (2852) | 377 (20) | 2475 (31) | |

| 8 (3188) | 647 (34) | 2541 (32) | |

| ≥ 9 (888) | 322 (17) | 566 (7) | |

| Aged 32–59 (5806) | |||

| ≤ 5 (493) | 31 (11) | 462 (8) | 12.64 (P = 0.0132) |

| 6 (1247) | 50 (18) | 1197 (22) | |

| 7 (1921) | 81 (30) | 1840 (33) | |

| 8 (1816) | 85 (31) | 1731 (31) | |

| ≥ 9 (329) | 26 (10) | 303 (5) | |

| Aged 60–86 (3983) | |||

| ≤ 5 (419) | 202 (13) | 217 (9) | 83.57 (P < .0001) |

| 6 (702) | 248 (15) | 454 (19) | |

| 7 (931) | 296 (18) | 635 (27) | |

| 8 (1372) | 562 (35) | 810 (34) | |

| ≥ 9 (559) | 296 (18) | 263 (11) | |

Data are represented as number (%).

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics and Risk Factors for Mortality by Self Reported Sleep Duration

| Total subjects, no. (%) | Sleep, h |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 5 912 (9.3) | 6 1949 (19.9) | 7 2852 (29.1) | 8 3188 (32.6) | ≥ 9 888 (9.1) | ||

| Continuous variablesa | F(P value) | |||||

| Age, y | 58.9 (14.6) | 55.3 (14.2) | 54.1 (13.7) | 57.1 (14.7) | 64.1 (15.4) | 93.1 (P < 0.0001) |

| Physical activity, score | 3.6 (1.2) | 4.0 (1.1) | 4.0 (1.1) | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | 38.6 (P < 0.0001) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.3 (7.4) | 26.9 (7.7) | 26.2 (6.5) | 26.3 (6.5) | 27.0 (11.7) | 6.5 (P < 0.0001) |

| General health | 3.2 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.2) | 115.4 (P < 0.0001) |

| Daytime sleepiness | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.4) | 23.0 (P < 0.0001) |

| Nighttime awakening | 3.3 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.3) | 101.7 (P < 0.0001) |

| Categorical variablesb | X2 (P value) | |||||

| Diabetes | 10.2 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 7.1 | 10.8 | 41.8 (P < 0.0001) |

| Hypertension | 68.1 | 59.2 | 53.3 | 57.6 | 68.2 | 102.7 (P < 0.0001) |

| Cancer | 10.2 | 8.5 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 12.7 | 20.7 (P = 0.0004) |

| Cigarette smoker | 28.6 | 30.0 | 27.7 | 24.8 | 20.8 | 35.7 (P < 0.0001) |

| Depression | 35.9 | 20.0 | 13.2 | 15.8 | 21.6 | 261.3 (P < 0.0001) |

| Women | 65.9 | 61.5 | 62.7 | 63.5 | 61.0 | 6.9 (P = 0.1407) |

| High-school graduate | 49.2 | 64.1 | 69.4 | 60.7 | 45.6 | 234.0 (P < 0.0001) |

| Non-Caucasian | 20.9 | 17.1 | 11.1 | 13.3 | 17.3 | 76.7 (P < 0.0001) |

| Living alone | 21.3 | 16.6 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 23.3 | 76.3 (P < 0.0001) |

| Low income | 40.6 | 25.0 | 20.7 | 27.5 | 41.2 | 233.7 (P < 0.0001) |

| Sleeping pill use | 16.6 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 9.5 | 114.6 (P < 0.0001) |

Data for continuous variables are shown as mean (SD). Activity level is rated from 6, high, to 2, low. Daytime sleepiness and nighttime awakening are rated 1–5, correlating with never, rarely, sometimes, often, or almost always, respectively. BMI refers to body mass index.

Data for categorical variables are shown as percentage of total subjects.

Table 5 shows the HR for mortality over the 8- to 10-year follow-up period, as computed with Cox proportional hazards models. In the unadjusted results (Model 1) for the total sample between the ages of 32 and 86 years, subjects with both short and long sleep durations were significantly more likely to die over the follow-up period than were subjects who reported sleeping 7 hours. The results were attenuated with the inclusion of the demographic and other variables in Model 2 and were further attenuated with the inclusion of diabetes, body weight, and hypertension in Model 3, but both short and long sleep durations continued to be significantly associated with increased mortality. The inclusion of the general health variable and cancer in Model 4 further attenuated the results, and the association between short sleep duration and mortality fell just out of statistical significance. The results differ though between the middle-aged and older subjects. In the unadjusted model with middle-aged subjects between the ages of 32 and 59, short sleep duration was associated with a statistically insignificant increased mortality risk (HR = 1.51, 95% CI 0.96–2.28), but, after adjusting for the covariates in the multivariate models, the association changed to a statistically insignificant decreased mortality risk (HR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.43–1.05). Long sleep duration was associated with a significantly increased mortality risk in the unadjusted model with middle-aged subjects, but, after adjusting for the covariates, the association was dramatically attenuated and fell out of statistical significance (HR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.66–1.65). Older subjects between the ages of 60 and 86 who reported sleeping 5 hours or less and who reported sleeping 9 hours or more were significantly more likely to die over the follow-up period. After adjusting for the potential mediators and confounders (Model 4), those who slept 5 hours or less per night (HR = 1.27, 95% CI 1.06–1.53) and those who slept 9 hours or more per night (HR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.15–1.60) continued to be significantly more likely to die over the follow-up period. The interaction term included in regression models to investigate whether age (ages 32 to 59 vs 60 to 86 years) acted as an effect modifier in the relationship between short sleep duration (≤ 5 hours vs 7 hours) and mortality was significant (p = .03), whereas the interaction term for age and long sleep duration (≥ 9 hours vs 7 hours) was not (p = .19).

Table 5.

Hazards Ratios (95% Confidence Interval) for Mortality Over the Follow-Up Period by Sleep Duration at Baseline

| Amount of sleep, h | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 9789) | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 2.08 (1.77–2.45) | 1.28 (1.08–1.52) | 1.26 (1.06–1.49) | 1.17 (0.99–1.39) |

| 6 | 1.17 (1.01–1.36) | 0.98 (0.84–1.14) | 0.96 (0.83–1.12) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) |

| 7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8 | 1.60 (1.41–1.82) | 1.23 (1.08–1.39) | 1.22 (1.07–1.39) | 1.23 (1.08–1.39) |

| ≥ 9 | 3.18 (2.74–3.69) | 1.40 (1.20–1.62) | 1.37 (1.17–1.59) | 1.34 (1.15–1.56) |

| Aged 32–59 (n = 5806) | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 1.51 (0.96–2.28) | 0.82 (0.53–1.28) | 0.76 (0.49–1.19) | 0.67 (0.43–1.05) |

| 6 | 0.95 (0.67–1.36) | 0.84 (0.59–1.19) | 0.81 (0.56–1.15) | 0.75 (0.53–1.08) |

| 7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8 | 1.11 (0.82–1.51) | 1.09 (0.80–1.47) | 1.05 (0.77–1.43) | 1.02 (0.75–1.38) |

| ≥ 9 | 1.90 (1.22–2.96) | 1.35 (0.86–2.12) | 1.19 (0.76–1.88) | 1.04 (0.66–1.65) |

| Aged 60–86 (n = 3983) | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 1.72 (1.44–2.06) | 1.36 (1.13–1.64) | 1.34 (1.11–1.61) | 1.27 (1.06–1.53) |

| 6 | 1.14 (0.96–1.35) | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 0.99 (0.84–1.18) | 0.98 (0.83–1.17) |

| 7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8 | 1.38 (1.20–1.59) | 1.25 (1.08–1.44) | 1.24 (1.08–1.43) | 1.25 (1.09–1.44) |

| ≥ 9 | 1.98 (1.68–2.32) | 1.41 (1.19–1.66) | 1.38 (1.17–1.63) | 1.36 (1.15–1.60) |

Model 1 – Unadjusted.

Model 2 – Adjusted for age, physical activity, smoking, depression, sex, education, living alone, low income, daytime sleepiness, nighttime awakening, ethnicity, and sleeping pill use.

Model 3 – Adjusted for variables in Model 2 plus body weight, diabetes, and hypertension.

Model 4 – Adjusted for variables in Model 3 plus general health and cancer.

In analyses stratified by sex, short sleep duration was associated with mortality in women in the unadjusted model (Model 1) (HR = 2.04, 95% CI 1.63–2.55) but not in the fully adjusted model (Model 4) (HR = 0.99, 95% CI 0.77–1.24). Other studies have shown mixed results in the relationship between short sleep duration and mortality in women in fully adjusted models, with some showing significant results26,27 and others showing nonsignificant results.28,29 Short sleep duration in men and long sleep duration in both men and women were associated with mortality in fully adjusted models. The interaction term included in regression models to explore whether sex acted as an effect modifier in the relationship between short sleep duration and mortality was significant (p = .02), whereas the interaction term for sex and long sleep duration was not (p = .85).

Contrary to the results from the bivariate analyses, an increased number of cigarettes smoked and higher body mass index were not associated with decreased mortality in fully adjusted multivariate analyses. Smoking a pack or more of cigarettes per day was associated with a significantly increased risk for mortality (HR = 1.59, 95% CI 1.36–1.85), in comparison with abstinence from smoking. In comparison with subjects who had normal bodyweights, subjects who were underweight were significantly more likely to die over the follow-up period (HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.26–1.91), and subjects who were overweight were significantly less likely to die over the follow-up period (HR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.75–0.92). Obese and morbidly obese subjects were not more likely nor less likely than normal weight subjects to die over the follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with the results from other epidemiologic studies on the relationship between sleep duration and mortality, in multivariate analyses that included subjects of all ages, we found a U-shaped relationship, with both short and long sleep durations being associated with higher mortality. Our results differ, though, in multivariate analyses stratified by age. We found a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and mortality in elderly subjects between the ages of 60 and 86 but found no relationship in fully adjusted models in middle-aged subjects between the ages of 32 and 59. The lack of an association between short sleep duration and mortality in middle-aged subjects was surprising in light of evidence from previously conducted experimental and epidemiologic studies, which identified links between short sleep and diabetes, obesity, and hypertension, conditions that are associated with increased mortality risk. Short sleep duration is associated with increased incidences of these conditions in middle-aged subjects, but perhaps new cases of these chronic conditions do not ultimately lead to death until later in the subjects' lives, when they are elderly. In elderly subjects, the association between short sleep duration and mortality was only modestly attenuated with the inclusion of diabetes, body weight, and hypertension in Model 3. The small degree of change in the HR could have been due to the fact that sleep duration has been found not to be associated with hypertension incidence12 and obesity8 in elderly subjects in the NHANES I. Short sleep duration has also been theorized to mediate the association between socioeconomic status and poor health,30 so the attenuation in the HR resulting from the inclusion of variables such as low income and education in Model 2 could have been partially attributable to the association between these socioeconomic variables and diabetes, body weight, and hypertension.

The subjects' sleep durations that they reported an average of 4.9 years before their deaths were unlikely to have been indicative of their sleep durations over the course of their lifetimes, which would have been when they were developing the chronic diseases that eventually contributed toward their deaths. If we presume that sleep durations are stable, then, as individuals age and pass away, we would expect that, due to the lower mortality associated with 7-hour sleep durations and the higher mortality associated with short and long sleep durations, progressively older age groups would have increasingly higher percentages of subjects reporting 7-hour sleep durations and increasingly lower percentages of subjects reporting short and long sleep durations. However, the data from this study show the opposite trends. We found that progressively older age groups had increasingly lower percentages of subjects who reported 7-hour sleep durations and increasingly higher percentages who reported long and short sleep durations. The most likely explanations for this finding are a cohort effect and changes in sleep durations over time, whereby, as individuals age, they become less likely to sleep 7 hours and more likely to sleep 5 hours or less or 9 hours or more.

One plausible explanation for the U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and mortality in elderly subjects relates to the close proximity in time between the sleep-duration measurement and death. Sleep durations measured closely to the time of death may be influenced by the presence of medical conditions that eventually contributed toward the subjects' deaths. More than 75% of the deaths in elderly subjects were attributable to major cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes. The inflammatory process has been shown to play key roles in both the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of cancer31 and of metabolic disorders such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.32,33 The human immune response involves a dynamic and ever-shifting balance between proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines.34 Proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-2 have been shown to promote sleep, whereas antiinflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 have been shown to inhibit sleep.35,36 The sleep durations of elderly subjects at baseline may therefore have been either shortened or lengthened as a result of inflammatory responses to medical conditions, conditions that, over follow-up, ultimately played a part in the subjects' deaths. The ability of the potentially mediating variables (diabetes, body weight, hypertension, general health, and cancer) to attenuate the associations between sleep duration and mortality when added to the multivariate models may therefore have been due to the influence of medical conditions on sleep duration.

The associations between short and long sleep durations and mortality in the elderly may be reflective of disturbances in the central biologic clock or suprachiasmatic nucleus. The suprachiasmatic nucleus evolved to rely upon repeated physiologic cues from both the external and internal environments in order to synchronize rest and activity to the circadian and seasonal cycles that change in a precise and predictable fashion. The cumulative effects of repeated and prolonged exposures to alterations in the timing and duration of light, sleep, and activity during the last century in industrialized countries could disturb the functioning of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in elderly subjects. Disturbances in the suprachiasmatic nucleus have been shown to contribute toward diseases associated with the metabolic syndrome,37,38 so these disturbances could have contributed to both premature death and changes in average sleep duration.

There has been much debate about what sleep durations in humans should be considered “normal” or “natural.” Consideration of the circadian and seasonal rhythms of early humans can help address this issue. The length of the daily photoperiod at the equator is 12 hours, and, as the distance from the equator increases, the length of the longest summer light exposure increases to the extreme of 24 hours at the poles. Early humans who lived away from the equator would therefore have been exposed on a circannual basis to both shortened and lengthened photoperiods, inducing shorter sleep durations in summer and longer sleep durations in winter. Periodic exposure to photoperiods of longer or shorter than 12 hours would have been expected, but prolonged or year-round exposure to either of these extremes would have been anomalous. Since the circadian rhythms of early humans were more closely synchronized to the rising and setting of the sun, it is likely that their sleep durations were longer than 8 hours during a majority of the year. In a study with healthy male subjects, exposure to a cycle of 10 hours of light and 14 hours of darkness for 4 weeks resulted in a natural tendency to sleep more than 8 hours when there was ample time in bed with no distractions.39

Although the findings from this study show differences by age in the association between sleep duration and mortality, a number of limitations to these analyses must be considered as well. An important question is whether there was an adequate sample size in middle-aged subjects to detect an association between sleep duration and mortality in multivariate analyses. The sample size of middle-aged subjects (n = 5806) was high relative to the sample size of elderly subjects (3983), but the average age at death was 76.6 years, and, as would be expected, the majority of deaths occurred among the elderly (n = 1604), whereas comparatively few deaths occurred among the middle-aged subjects (n = 273). The lack of an association between sleep duration and mortality in multivariate models in the middle-aged subjects could therefore be due to a lack of statistical power and, therefore, could represent a type II error. The use of self-reported sleep durations, as opposed to measured sleep durations, represents another limitation of this study. Although some studies have found good agreement between self-reported sleep durations and those measured through actigraphic monitoring,40,41 other studies have found self-reported sleep durations to overestimate those measured through actigraphic42 and polysomnographic43 monitoring. The NHANES I also lacked repeated measures of sleep duration, so we have no way of knowing how representative the baseline sleep measure was of the sleep duration over the follow-up period. Changes in sleep patterns over the follow-up period could have weakened the association between sleep duration reported at baseline and mortality. We were also unable to fully control in our analyses for the presence of sleep disordered breathing, which has been found to be associated with mortality.44 Subjects with sleep disorders could be more likely to self report short sleep durations due to poor sleep quality or, conversely, could be more likely to self report long sleep durations due to increased time in bed to compensate for poor sleep quality. The NHANES I Follow-up survey did not include questions on sleep disorders but did include questions on daytime sleepiness and nighttime awakening, which are associated with sleep disordered breathing.45 Our multivariate models included variables for daytime sleepiness and nighttime awakening, therefore at least partially controlling for sleep disorders. Other limitations include possible bias arising from loss to follow-up and missing data on baseline risk variables.

The question arises whether the timing of the deaths in this cohort were premature or were simply reflective of the normal variability in an outcome that is universal. Everyone will eventually die, and the average life expectancy in the industrialized world is about 75 years. The longest recorded life spans have been around 120 years, and the ability to live longer lives depends upon numerous genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors. When exploring whether clinical and behavioral exposures are risk factors for premature death, subjects would ideally be followed over the course of their lives to obtain repeated measures of exposures to gauge their ultimate influence over the life course upon morbidity and mortality. It would also be preferable to have repeated measurements of all potential confounders and mediators of the relationship between the exposure of interest and mortality. Single measurements of exposures closely before death can result in unadjusted findings that are counterintuitive. We found morbid obesity and smoking a pack or more of cigarettes per day to be associated with a lower probability of death over the follow-up period in unadjusted analyses. Controlling for potential confounders and mediators in multivariate analyses removed any impression that these well-established risk factors for mortality were protective against premature death. Just as we would not conclude from unadjusted results that morbid obesity and cigarette smoking are protective against premature death, we should look with skepticism on unadjusted findings generated from data gathered so closely to the time of death. We found sleep duration to be related to mortality in middle-aged and elderly subjects in unadjusted analyses, but, after controlling for covariates in multivariate analyses, sleep duration was associated with mortality only in elderly subjects. These findings call into question the appropriateness of recommending sleep restriction to all age groups in an effort to lower mortality risk.

The results from this study suggest that the U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and mortality is heavily influenced by deaths in elderly subjects and by the measurement of sleep durations closely before death. It is possible that the sleep durations of the elderly subjects who died were affected by the presence of medical conditions that eventually contributed toward the subjects' deaths. The elderly subjects' immune responses to these conditions could have resulted in a predominance of either proinflammatory or antiinflammatory cytokines that functioned to shorten or lengthen sleep. The association between short sleep duration and mortality could also be partially attributable to the influence of short sleep duration on insulin sensitivity, body weight, and blood pressure. The potential for sleep duration to function as a surrogate marker of medical conditions that are associated with increased mortality and the close proximity between the exposure of sleep and the outcome of mortality weaken our ability to infer whether sleep duration is associated with mortality in elderly subjects. Future studies on the relationship between sleep duration and mortality would ideally include repeated measures of sleep duration and long follow-up durations to appropriately assess the influence of sleep length on health over the life course. The results from this study, coupled with the lack of evidence that sleeping longer than 8 hours is detrimental to health, imply that long sleep duration is unlikely to contribute toward mortality but, rather, is a consequence of conditions associated with chronic inflammation and age-related sleep changes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support for this study was provided by R24 HL76857 from the NIH/National Heart Blood and Lung Institute to Columbia University's Behavioral Cardiovascular Health & Hypertension Program. Work was performed at Columbia University, New York, NY.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Heymsfield is an Executive Director, Clinical Studies, at Merck and Co. Dr. Zammit has received research support from Ancile Pharmaceuticals, Arena, Aventis, Cephalon, Elan, Epix, Evotec, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, H. Lundbeck A/S, King, Merck, Neurim, Neurocrine Biosciences, Neurogen, Organon, Orphan Medical, Pfizer, Respironics, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Somaxon, Takeda, Transcept, UCB Pharma, Predix, Vanda, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has consulted for Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cephalon, Elan, GlaxoSmithKline, Jazz, King, Merck, Neurocrine Biosciences, Organon, Pfizer, Renovis, Sanofi-Aventis, Select Comfort, Sepracor, Shire, and Takada; has received honoraria from Neurocrine Biosciences, Kink, McNeil, Sanofi-Aventis, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Sepracor, Shire, and Takeda; and has ownership/Directorship in Clinilabs, Inc., Clinilabs IPA, Inc., and Clinilabs Physician Services, PC. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Youngstedt SD, Kripke DF. Long sleep and mortality: rationale for sleep restriction. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:159–74. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.VanHelder T, Symons JD, Radomski MW. Effects of sleep deprivation and exercise on glucose tolerance. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1993;6:487–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet. 1999;354:1435–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaggi HK, Araujo AB, McKinlay JB. Sleep duration as a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:657–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, et al. Sleep duration as a risk factor for diabetes incidence in a large U.S. sample. Sleep. 2007;30:1667–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:845–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gangwisch JE, Malaspina D, Boden-Albala B, Heymsfield SB. Inadequate sleep as a risk factor for obesity: Analyses of the NHANES I. Sleep. 2005;28:1289–96. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel SR, Malhotra A, White DP, Gottlieb DJ, Hu FB. Association between reduced sleep and weight gain in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;16:947–54. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tochikubo O, Ikeda A, Miyajima E, Ishii M. Effects of insufficient sleep on blood pressure monitored by a new multibiomedical recorder. Hypertension. 1996;27:1318–24. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lusardi P, Zoppi A, Preti P, Pesce RM, Piazza E, Fogari R. Effects of insufficient sleep on blood pressure in hypertensive patients: a 24-h study. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:63–8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, et al. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension: Analyses of the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension. 2006;47:833–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217362.34748.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappuccio FP, Stranges S, Kandala NB, et al. Gender-specific associations of short sleep duration with prevalent and incident hypertension. The Whitehall II Study. Hypertension. 2007;50:694–701. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knutson KL, Turek FW. The U-shaped association between sleep and health: the 2 peaks do not mean the same thing. Sleep. 2006;29:878–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.7.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gisquet V. Ten ways to live longer. [Accessed on May 22, 2008]; Available at: http://www.forbes.com/2006/04/28/cx_vg_0501featslide2.html?thisSpeed=6000.

- 16.Webb WB. Age-related changes in sleep. Clin Geriatr Med. 1989;52:275–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (distributor); 1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I: Epidemiologic Followup Study, 1982–1984 (computer file). 2nd release. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Services (producer), 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research distributor; 1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I: Epidemiologic Followup Study, 1986 computer file. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Services producer, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research distributor; 1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I: Epidemiologic Followup Study, 1987 computer file. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Services producer, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research distributor; 1997. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I: Epidemiologic Followup Study, 1992 computer file. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Services producer, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff LS, Locke BZ. The community mental health assessment survey and the CES-D scale. In: Weissman MM, Myers JK, Ross CE, editors. Community Surveys of Psychiatric Disorders. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1986. pp. 177–89. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Sleep Foundation. Executive summary of the 2003 Sleep in America Poll. [Accessed on May 22, 2008]; Available at: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/site/c.huIXKjM0IxF/b.2417365/k.1460/2003_Sleep_in_America_Poll.htm.

- 23.SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC: The SAS System for Windows, Version 9.0. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Research Triangle Institute (2002) Research Triangle Park, NC: SUDAAN Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data, Release 8.0.1 for PCs SAS Callable Version, [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingram DD, Makuc DM. Statistical issues in analyzing the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Series 2: Data evaluation and methods research. Vital Health Stat 2. 1994;121:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y. Self-reported sleep duration as a predictor of all-cause mortality: results from the JACC Study, Japan. Sleep. 2004;27:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J. Sleep complaints predict coronary artery disease mortality in males: a 12-year follow-up study of a middle-aged Swedish population. J Intern Med. 2002;251:207–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel SR, Ayas NT, Malhotra MR, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women. Sleep. 2004;27:440–4. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Cauter E, Spiegel K. Sleep as a mediator of the relationship between socioeconomic status and health: A hypothesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;896:254–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dranoff G. Cytokines in cancer pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev. 2004;4:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haffner SM. The metabolic syndrome: Inflammation, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:3A–11A. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Opal SM, DePalo VA. Anti-inflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;117:1162–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.4.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krueger JM, Majide JA. Humoral links between sleep and the immune system. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;992:9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krueger JM, Obal FG, Fang J, Kubota T, Taishi P. The role of cytokines in physiological sleep regulation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;933:211–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kreier F, Kalsbeek A, Sauerwein HP, Fliers E, Romijn JA, Buijs RM. “Diabetes of the elderly” and type 2 diabetes in younger patients: possible role of the biological clock. Exper Gerontol. 2007;42:22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kreier F, Yilmaz A, Kalsbeek A, et al. Hypothesis: Shifting the equilibrium from activity to food leads to autonomic unbalance and the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2003;52:2652–56. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wehr TA, Moul DE, Barbato G, et al. Conservation of photoperiod-responsive mechanisms in humans. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R846–57. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.4.R846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lockley SW, Skene DJ, Arendt J. Comparison between subjective and actigraphic measurement of sleep and sleep rhythms. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:175–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hauri PJ, Wisbey J. Wrist Actigraphy in insomnia. Sleep. 1992;15:293–301. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, et al. Objectively measured sleep characteristics among early-middle-aged adults. The CARDIA Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:5–16. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsleben JA, Kapur VK, Newman AB, et al. Sleep and reported daytime sleepiness in normal subjects: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2004;27:293–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levie P, Herer P, Peled R, Berger I, Yoffe N, Zomer J, Rubin AH. Mortality in sleep apnea patients: a multivariate analysis of risk factors. Sleep. 1995;18:149–57. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.3.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malhotra A, White DP. Obstructive sleep apnea. Lancet. 2002;360:237–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09464-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]