Abstract

A monophyletic group of black yeast-like fungi containing opportunistic pathogens around Exophiala spinifera is analyzed using sequences of the small-subunit (SSU) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) domains of ribosomal DNA. The group contains yeast-like and annellidic species (anamorph genus Exophiala) in addition to sympodial taxa (anamorph genera Ramichloridium and Rhinocladiella). The new species Exophiala oligosperma, Ramichloridium basitonum, and Rhinocladiella similis are introduced and compared with their morphologically similar counterparts at larger phylogenetic distances outside the E. spinifera clade. Exophiala jeanselmei is redefined. New combinations are proposed in Exophiala: Exophiala exophialae for Phaeococcomyces exophialae and Exophiala heteromorpha for E. jeanselmei var. heteromorpha.

A significant portion of the species of black yeasts and their filamentous relatives, anamorphs of members of the order Chaetothyriales, are regularly encountered as causative agents of human mycoses (9). They exhibit a relatively high degree of molecular diversity (10) but seem to possess common factors which enable them to invade the human host, resulting in a bewildering diversity of mycoses, such as chromoblastomycosis, mycetoma, brain infection, and other types of phaeohyphomycosis (9). In harboring a wide array of clinically relevant species, the Chaetothyriales are unique in the fungal kingdom: they are only matched by the Onygenales, the order containing the dermatophytes and the dimorphic pathogens. Understanding the species diversity of the Chaetothyriales and their specific ecology is of considerable medical relevance.

This wide species spectrum is only poorly understood, as until recently insufficient markers were available for a reliable distinction of taxa. Morphology is poorly developed in these fungi, and when present, very similar microscopic structures can be expressed in phylogenetically remote species (15). Sequencing studies of the ribosomal operon have shown that this gene can be successfully applied to species delimitation and identification. A large number of new taxa have to be introduced; many of these have a pathogenic potential.

In an extended 18S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequencing study of black yeasts and their allies, Haase et al. (15) showed that the phylogenetic tree of the Chaetothyriales is poorly resolved, which indicates a radiation of taxa within a relatively short evolutionary period. All anamorph genera concerned proved to be polyphyletic (15); the morphological entities were nevertheless maintained for practical reasons. The single teleomorph genus in the order, Capronia, was found throughout the tree but appeared to have limited clinical relevance.

One of the few recognizable clades with convincing statistical support was the Exophiala spinifera-E. jeanselmei complex. Detailed studies of the small-subunit (SSU) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rDNA domains of this group (11, 43) demonstrated that the clade contains the known species E. spinifera (Nielsen et Conant) McGinnis, E. jeanselmei (Langer) McGinnis et Padhye, E. attenuata Vitale et de Hoog, Phaeococcomyces exophialae de Hoog, and a hitherto unidentified Exophiala sp. represented by strain CBS 725.88 from a systemic mycosis in an adult (38). E. jeanselmei has been associated with human mycetoma (19) and with a chromoblastomycosis-like skin disorder (28), whereas E. spinifera causes local skin infections in adults or disseminated disease in adolescents (11). Thus, this clade comprises species with considerable opportunistic potential.

E. jeanselmei has long been recognized as heterogeneous. Based on morphology, de Hoog (7) recognized three varieties, which are now known to represent separate, distantly related species (15, 45). E. jeanselmei-like strains may show two dissimilar phenotypes: one is annellidic, as in Exophiala, and the other is sympodial, as in Rhinocladiella (7). Similar observations have been made in Rhinocladiella atrovirens (Nannf.) de Hoog, where the two types of conidiation were observed to be located even on a single hypha (7). For this reason, some sympodial species classified in Rhinocladiella and Ramichloridium, including some undescribed isolates, are included in the present taxonomic study. The molecular interrelationships of the taxa discussed above were studied using 18S rDNA and ITS sequence analyses, and an investigation was done to determine whether the various mycoses caused by these organisms can consistently be attributed to specific taxonomic entities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and morphology.

The strains studied are listed in Table 1. This list comprises strains of the E. spinifera clade (15) supplemented with strains which were morphologically or phylogenetically supposed to belong to the group. Stock cultures were maintained on slants of 2% malt extract agar and oatmeal agar at 24°C. For morphological observation, slide cultures were made of strains grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and mounted in lactophenol cotton blue.

TABLE 1.

Strains examineda

| Original name | CBS no. | Statusb | Other reference(s) | GenBank no. | Source | Final identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exophiala sp. | 109807 | DH 12229 = Ej5 Attili | AY163557 | Fungemiac, Brazil | E. oligosperma | |

| M. oligospermus | 265.49 | AUT | MUCL 9905 | AY163555 | Honey, France (5) | E. oligosperma |

| AF050289 | ||||||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 12700 = Tm 01.109-II | Silicone solution, Netherlands | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 12701 = Tm 01.109-IIA | Silicone solution, Netherlands | E. oligosperma | |||

| E. jeanselmei | 463.80 | Scholer D-5014 | AY163552 | Prosthetic eye lense, Switzerland | E. oligosperma | |

| E. jeanselmei | 715.76 | UAMH 2627 = GHP 1406 | Cedar wood of cooling tower, Canada | E. oligosperma | ||

| Exophiala sp. | IFM 5386 | Unknown source | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 12896 | Water, Germany | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 12713 = GHP 2097 | Plastic foil, Germany | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 12586 = Mayr 131 | Sauna, Austria | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala sp. | 725.88 | T | AY163551 | Sphenoid tumorc, female, Germany (38) | E. oligosperma | |

| Rhinocladiella sp. | RKI 384 II/02 | Skin lesionc, Germany | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala aff. spinifera | DH 12578 | Skin lesion of sharkc, Zoo Rotterdam, Netherlands | E. oligosperma | |||

| E. jeanselmei | 814.95 | AY163549 | Soil biofilter, Netherlands (6) | E. oligosperma | ||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 11646 = IWW 533 | Swimming pool, Germany | E. oligosperma | |||

| E. jeanselmei | UTHSC 98-911 = Nucci 10 = dH 12909 | Sinus drain (30, 31) | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 12589 = Mayr 192 | Sauna, Austria | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 12587 = Mayr 141 | Sauna, Austria | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 12585 = Mayr 130 | Sauna, Austria | E. oligosperma | |||

| Exophiala sp. | IFM 41701 | AY163548 | Soil | E. oligosperma | ||

| Exophiala sp. | UTHSC 01-1637 | AY231163 | Olecranon Bursac, Texas (2) | E. oligosperma | ||

| E. jeanselmei | 835.95 | AY163550 | Mycetomac, Germany (29) | E. oligosperma | ||

| E. jeanselmei | DH 12841 | Bronchoalveolar lavage, Netherlands | E. oligosperma | |||

| R. aquaspersa | 313.73 | T | ATCC 24410 = FMC 241 | Chromomycosisc, Mexico (1) | R. aquaspersa | |

| R. atrovirens | 109135 | DH 11842 | AY163558 | Endoscope, Netherlands | R. similis | |

| R. atrovirens | 111763 | T | DH 11329 = HC-1 | AY040855 | Foot lesionc, Brazil (Resende et al., Abstr. 14th ISHAM) | R. similis |

| Unidentified | AJ279469 | R. similis | ||||

| Exophiala sp. | DH 12894 | Water | R. similis | |||

| Geniculosporium sp. | 101460 | T | IFM 47593 | AY163561 | Subcutaneous lesionc, Japan (37) | R. basitonum |

| E. nishimurae | 101538 | T | AY163560 | Contaminant (43) | E. nishimurae | |

| P. jeanselmei | 528.76 | ATCC 10224 | Skinc, United Status | |||

| E. jeanselmei | 507.90 = 664.76 | T | IHM 283 = ATCC 34123 = NCMH 1235 | AF05027 | Mycetomac, Martinique (19) | E. jeanselmei |

| E. spinifera | 109635 | UTMB 2670 = UTHSC 86-72 | Arm lesionc, Texas | E. jeanselmei | ||

| E. jeanselmei | 116.86 | AY163556 | Skin lesionc, Japan (28) | E. jeanselmei | ||

| E. jeanselmei | 677.76 | IHM 1586 | AY163553 | Mycetomac, United Kingdom (27) | E. jeanselmei | |

| M. eumetabolus | 264.49 | AUT | MUCL 9904 | AY163554 | Honey, France (3, 4) | R. atrovirens |

| R. anceps | 181.65 | NT | ATCC 18655 = IMI 134453 = MUCL 8233 | Soil, Canada | R. anceps |

For data on strains of E. spinifera and E. exophialae, see De Hoog et al. (11). ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.; CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; DH, G. S. de Hoog private collection; IFM, Research Institute for Pathogenic Fungi, Chiba, Japan; IHM, Laboratory of Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, Montevideo Institute of Epidemiology and Hygiene, Montevideo, Uruguay; IMI, International Mycological Institute, London, United Kingdom; IWW, Rheinisch Westfählisches Institut für Wasserforschung, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany; GHP, G. Haase private collection; MUCL, Mycotheque de l'Université de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium; NCMH, North Carolina Memorial Hospital, Chapel Hill, N.C.; RKI, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany; UAMH, Microfungus Herbarium and Collection, Edmonton, Canada; UTHSC, Fungus Testing Laboratory, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Tex.; UTMB, Medical Mycology Research Center, Galveston, Tex.; aff., with affinity to.

T, former type culture; NT, former neotype culture; AUT, authentic culture.

Confirmed etiological agent.

DNA extraction.

Mycelia (∼1 cm2 each) of 30-day-old cultures were transferred to 2-ml Eppendorf tubes containing 300 μl of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide buffer and ∼80 mg of a silica mixture (silica gel H [catalog no. 7736; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany] or Kieselguhr Celite 545 [Machery, Düren, Germany]) (2:1 [wt/wt]). The cells were disrupted mechanically with a tight-fit sterile pestle for ∼1 min. Subsequently, 200 μl of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide buffer was added, and the mixture was vortexed and incubated for 10 min at 65°C. After the addition of 500 μl of chloroform, the solution was mixed and centrifuged for 5 min at 20,800 × g, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube with 2 volumes of ice-cold 96% ethanol. DNA was allowed to precipitate for 30 min at −20°C, and then the solution was centrifuged again for 5 min at 20,800 × g rpm. Subsequently, the pellet was washed with cold 70% ethanol. After drying at room temperature, it was resuspended in 97.5 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer (14) plus 2.5 μl of 20-U · ml−1 RNase and incubated for 5 min at 37°C.

Sequencing and phylogenetic reconstruction.

ITS amplicons were generated for all strains using primers V9D and LS266 (14) and cleaned using Microspin S-300 HR columns (Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany). Sequencing was performed on an ABI 310 automatic sequencer. SSU amplicons were generated with primers NS1 and NS24 and sequenced with primers Oli1, Oli5, Oli9, Oli10, BF951, BF963, Oli2, Oli3, Oli13, Oli14, BF 1419, BF 1438, and Oli15 (9); spacer domains were amplified with V9G and LS266 and sequenced with ITS1 and ITS4. Sequences were verified using the SeqMan package (DNAStar Inc., Madison, Wis.) and aligned using BioNumerics version 3.0 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). The specificities of ITS sequence signatures were verified by developing specific primers and subsequently testing them by PCR. The Treecon package version 1.3b (41) was applied to generate a distance tree using the neighbor-joining algorithm with Kimura correction; only unambiguously aligned positions were taken into account. One hundred bootstrap replicates were used for analysis. The topologies of the resulting trees were verified using the parsimony option in BioNumerics. SSU sequences were aligned using DCSE (13), and a tree of Chaetothyriales was constructed using Treecon with the algorithm mentioned above.

RESULTS

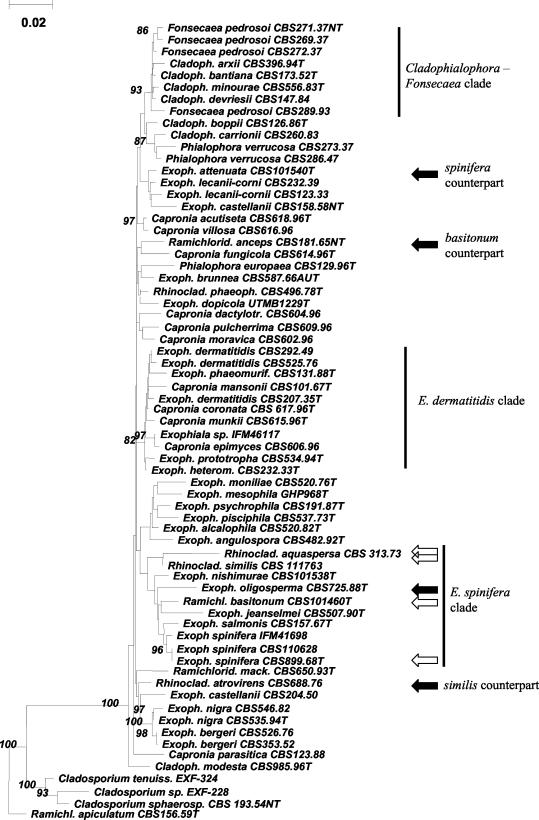

An SSU rDNA neighbor-joining tree containing 71 purported ana- and teleomorphic members of the Chaetothyriales and some related species is presented in Fig. 1. Ramichloridium apiculatum (CBS 156.59) was taken as the outgroup, as it is known to cluster among Dothideales (G. S. de Hoog, unpublished data). The E. spinifera clade comprised strains IFM 41855, CBS 725.88, CBS 101460, CBS 507.90, CBS 157.67, IFM 41698, CBS 668.76, CBS 101538, and CBS 899.68. The clade did not contain any teleomorph. Most species were annellidic and therefore morphologically classified in Exophiala; HC-1 and CBS 101460 were sympodial and were attributed to the genera Rhinocladiella and Ramichloridium, respectively. Relevant species of Rhinocladiella and Ramichloridium, viz., Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, R. atrovirens, and Ramichloridium anceps, were found outside the E. spinifera clade.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of SSU rDNAs of 71 members of the black yeasts and relatives, constructed with the neighbor-joining algorithm in the Treecon package with Kimura-2 correction and 100 bootstrap replicates (values of >80 are shown with the branches). R. apiculatum CBS 156.59, known to be related to Cladosporium, is taken as the outgroup. The E. dermatitidis, Cladophialophora-Fonsecaea, and E. spinifera clades are shown. The open and solid arrows indicate new species and their morphologically similar but phylogenetically remote counterparts. Cladoph., Cladophialophora; Exoph., Exophiala; Ram., Ramichloridium; Rhinoclad., Rhinocladiella. The nomenclature used is according to our conclusions (see Table 1).

For the ITS tree (Fig. 2), the same species listed above in the SSU E. spinifera clade could be aligned with confidence, except for IFM 41698, a hitherto-unidentified Exophiala species. Nine more or less clearly delimited clusters or single strains were found, four of which contained ex-type cultures of existing species. Cluster 9 contained CBS 264.49, the ex-type culture of the invalidly described species Melanchlenus eumetabolus (3), and a number of strains identified as R. atrovirens from coniferous wood in the northern hemisphere. The cluster was aligned with difficulty with the remaining strains studied. CBS 101358, the ex-type culture of E. nishimurae, and CBS 101460, which was morphologically a Ramichloridium species originally referred to as Geniculosporium sp. (37), were paraphyletic to the remaining members of the E. spinifera SSU clade, as was cluster 8 containing strains with E. jeanselmei-like morphology, which apparently represents a further, undescribed species. Cluster 3 contained CBS 668.76, the ex-type culture of P. exophialae. Cluster 4 contained CBS 889.68, the ex-type culture of E. spinifera. E. attenuata, with an E. spinifera-like morphology (43) was found outside the SSU E. spinifera clade; its ITS sequence could not be aligned with confidence. The large ITS cluster 1 contained the ex-type strain of the invalidly described species Melanchlenus oligospermus. It had a morphology close to that of E. jeanselmei, with slightly differentiated, rocket-shaped conidiogenous cells (see Fig. 4). A specific primer was developed for cluster 1 (5′-GGTAGGCCTGGTCTATCTGTTAT-3′). It was found to be consistently positive with members of this group but gave negative results or nonspecific reactions with the remaining species (see Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of ITS rDNAs of 42 strains belonging to the E. spinifera clade constructed with the neighbor-joining algorithm in the Treecon package with Kimura-2 correction and 100 bootstrap replicates (values of >85 are shown with the branches).

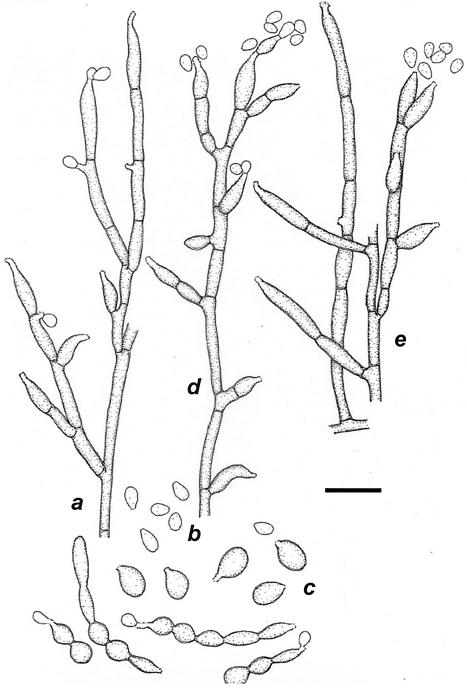

FIG. 4.

E. oligosperma CBS 245.49 (shown are the conidial apparatus [a and e], conidia [b], and germinating cells [c]) and E. jeanselmei UTMB 2670 (shown is the immature conidial apparatus [d]). Bar = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

General.

Comparisons using the nuclear SSU ribosomal gene have become the “gold standard” for fungal phylogeny (9). However, resolution at the species level may be inadequate. This is particularly the case in the order Chaetothyriales, containing the genus Capronia as well as the black yeasts and their filamentous relatives (15). The anamorph genera Cladophialophora, Cyphellophora, Exophiala, Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Rhinocladiella, Ramichloridium, and Veronaea are morphologically distinct but do not form separate clades in SSU phylogeny (15).

It is also remarkable that the teleomorphs in this family, though producing Exophiala, Phialophora, and Ramichloridium anamorphs in culture (39), are rarely observed to give rise to anamorphs that can be identified with known anamorph species (15, 40). In part, this may be due to different ecological preferences. Capronia species are mostly found colonizing other fungi, while the anamorphs without known teleomorphs are assimilators of aromatic compounds (26, 44) and are frequent opportunists on vertebrates (9). Generally, this is associated with differences in maximum growth temperatures. Most Capronia species are unable to grow above 35°C, and some are even psychrophilic (40), as are certain Exophiala species from cold water and/or fish, like E. psychrophila and E. mesophila (9). Two of the three Capronia species able to grow at 37°C, Capronia epimyces and Capronia munkii, cluster in the E. dermatitidis clade, which has an obvious thermophilic tendency (21). Fish pathogens and strictly environmental species are infrequent among the thermotolerant series containing Cladophialophora bantiana and Fonsecaea pedrosoi (Fig. 1).

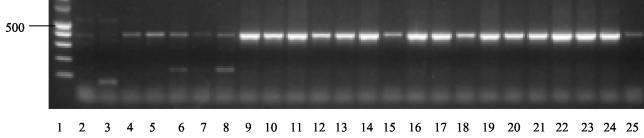

The value of the ITS domain for inferring phylogeny has been questioned by Lieckfeldt and Seifert (20). These authors found the marker to have insufficient variation to discriminate species in the evolutionarily recently diversified order Hypocreales. However, in the present study, the taxa analyzed show clear-cut delimitation, and the sequences of many species cannot even be aligned, indicating that the Chaetothyriales have a longer evolutionary history than the Hypocreales. Another argument against taxonomic use of ITS was particularly put forward by O'Donnell and Cigelnik (32), who pointed to the existence of paralogues in ITS2. This phenomenon has been reported repeatedly (16, 35, 42), sometimes with as many as three nonorthologous sequences being detected within the same repeat (34). We used two approaches to establish whether ITS sequences were likely to be orthologous. First, we verified that all entities distinguished by ITS (Fig. 2) also were markedly different by SSU rDNA (Fig. 1). This was invariably the case. Comparable independent sequence data are known in the mitochondrial cytochrome b protein, for which a similar taxonomic diversity of one of the umbrella species analyzed in the present article, E. jeanselmei, was found (44). Second, we developed specific primers for each of the entities with clearly different ITS sequences but lacking obvious phenetic characters. E. oligosperma PCR resulted in products different from those of the morphologically similar species E. jeanselmei and its annellidic counterpart species Rhinocladiella similis (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

PCR products of strains after using primers selective for E. oligosperma based on ITS sequences. Lanes: 1, size marker; 2 to 5, E. jeanselmei; 2, CBS 507.90; 3, CBS 528.76; 4, CBS 109635; 5, CBS 116.86; 6 to 8, R. similis; 6, DH 11329 = HC1; 7, CBS 109135; 8, DH 12894; 9 to 24, E. oligosperma; 9, CBS 463.80; 10, CBS 835.95; 11, DH 12578; 12, CBS 715.76; 13, DH 12586; 14, CBS 814.95; 15, CBS 725.88; 16, CBS 265.49; 17, DH 12713; 18, IFM 5386; 19, UTHSC 98-911; 20, DH 11646; 21, DH 12589; 22, DH 12587; 23, DH 12585; 24, DH 12896; 25, negative control.

The SSU rDNA-based E. spinifera clade as recognized by Haase et al. (15) was confirmed in the present study, with a larger number of strains. The sole exception was CBS 157.57, the former type strain of E. salmonis Carmichael, which previously took an isolated position in Haase's study (15). The ITS sequence of this species could not be aligned with confidence with the remaining members of the clade; rather, it was found to be close to a number of cold-water-inhabiting species, such as E. pisciphila McGinnis et Ajello (de Hoog, unpublished).

A large portion of the strains analyzed in the present study originated from environmental sources, but nearly all species also contained some clinical isolates. Consequently, it may be stated that the entire clade has an opportunistic potential and that clinical strains are likely to have basically the same genetic makeup as their environmental counterparts of the same species (43).

E. spinifera.

The clade under investigation contained three Exophiala species with more or less differentiated conidiogenous cells. E. spinifera in particular had erect, multicellular, dark-brown stalks producing conidia from terminal and intercalary cells (43). E. jeanselmei and E. oligosperma had nonseptate, rocket-shaped, slightly darkened conidiogenous cells. E. attenuata, which can be viewed as a distantly related counterpart of E. spinifera also having highly differentiated conidiophores, is located outside the E. spinifera clade (43). Otherwise, no Exophiala species are known to have such differentiated conidiogenous cells. Sixteen strains were identified as E. spinifera sensu stricto on the basis of morphology and ITS sequence similarity (Fig. 2).

E. exophialae.

P. exophialae de Hoog was originally introduced as a morphological umbrella species covering strictly budding yeasts with only some undifferentiated hyphae, which thus at that time could not be assigned to any known Exophiala species (7). De Hoog et al. (8) noted that E. exophialae and E. spinifera were identical in their physiological patterns, including the ability to grow at 37°C. In their ITS sequences, the three known strains of P. exophialae were closely related to but significantly different from E. spinifera. It was suggested that two separate species might be involved (11). Combination in Exophiala is morphologically confirmed, because the two strains later recognized as E. exophialae on the basis of sequence data were not strictly yeast-like but produced an annellidic anamorph consistent with the genus Exophiala. This anamorph lacked characteristic features that would allow identification on the basis of microscopy. Unlike E. spinifera, E. exophialae has never been found to have well-differentiated conidiophores. It should be noted, however, that a few strains identified as E. spinifera by their ITS sequences lacked differentiated conidiophores. E. exophialae is introduced formally below.

E. jeanselmei and E. heteromorpha.

The SSU-based clade under investigation further contained the ex-type strain of E. jeanselmei, CBS 507.90. According to the literature, E. jeanselmei has been among the black yeasts most commonly isolated from the environment, as well as from cases of mycosis. However, the species is known to be heterogeneous (17, 18, 22, 45). De Hoog (7) introduced three morphological varieties within the species. In an SSU phylogeny (15), later confirmed by Wang et al. (45) using mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences, E. jeanselmei var. lecanii-corni was found to be remote from E. jeanselmei and was therefore brought to species level as E. lecanii-corni (Benedek et Specht) Haase et De Hoog. E. jeanselmei var. heteromorpha was found to be a member of the E. dermatitidis clade, with 46 ITS nucleotides differing from those of E. jeanselmei CBS 507.90 (15) (Fig. 1). McKemy et al. (25) introduced the name Wangiella heteromorpha (Benedek et Specht) McKemy for this taxon. However, we believe that maintenance of the generic name Wangiella for just one of the Chaetothyrialean SSU clades containing annellidic anamorphs would be a random choice; moreover, there is no diagnostic character available for phenetic recognition of this clade (25). We therefore maintain the E. dermatitidis clade within Exophiala, which necessitates a new combination for Trichosporium heteromorphum Nannf. provided below.

Only two strains (UTMB 2670 and CBS 116.86 [Fig. 2]) showed <1% ITS sequence difference compared to the former type strain of E. jeanselmei, CBS 507.90, and thus were regarded as identical with this species. The infraspecific variability within the three strains is 3 bp in ITS1 and 6 bp (mainly indels) in ITS2. Strain CBS 507.90 originated from a well-described case of mycetoma in a patient in France originating from Martinique (19) but was not unequivocally confirmed as an etiologic agent. Strain CBS 116.86 was originally reported from a case referred to as chromoblastomycosis (28). Muriform cells were seen histopathologically in tissue, which is taken to be the hallmark of chromoblastomycosis (23). Thus, the tissue form is extremely different from that of the grains described by Langeron (19). However, despite the chronic nature (10 years) of the infection provoked by isolate CBS 116.86, swelling of the stratum spinosum with elevation of the lesion remained unremarkable. Some hyperkeratosis and hyperplasia were present (19). The case of CBS 116.86 infection is therefore evaluated as a very aberrant form of chromoblastomycosis. A further, unpublished case concerned a phaeohyphomycotic arm lesion caused by strain UTHSC 86-72 (43; D. Sutton, personal communication). CBS 677.76 originated from a black-grain mycetoma in a patient from Pakistan (27) and formed grains in vivo that were morphologically identical to those formed by CBS 507.90 (19). It had some sympodial conidiogenesis in addition to annellides and was therefore identified by de Hoog (7) as a poorly sporulating strain of R. atrovirens. However, sequencing revealed it to be close to E. jeanselmei (13 mutations or indels in ITS1 and 8 in ITS2). In contrast, sequences of four R. atrovirens strains could only partly be aligned to CBS 677.76 (de Hoog, unpublished). Also a significant SSU difference was noted (Fig. 1).

E. oligosperma.

A group of 23 strains (Table 1) were found to differ consistently from E. jeanselmei CBS 507.90 (Fig. 2) in 19 positions in ITS1 and an indel of 8 versus 20 bp in ITS2. The separation of the group was statistically supported, with high bootstrap values (Fig. 2). The group contains the ex-type strain of M. oligospermus Calendron (5), which was, however, simply mentioned in the text without any formal description and is therefore taxonomically invalid. Like E. jeanselmei, members of the group under consideration have rocket-shaped conidiogenous cells inserted laterally on hyphae, with a single terminal annellated zone which often is somewhat irregularly flared. Thus, the species can be phenetically closely similar to E. jeanselmei and has mostly been confused with that taxon (29, 30); less well-differentiated strains of the two species may be morphologically indistinguishable (Fig. 4). However, in characteristic cultures of E. jeanselmei, the conidiogenous cells arise at right angles from creeping hyphae and are somewhat darker than the remaining thallus (Fig. 5). Naka et al. (28) reported a granular morphotype in E. jeanselmei which is very similar to that seen in E. oligosperma by Neumeister et al. (29). Despite these similarities, we believe it is advisable to keep them apart, particularly because ITS sequencing, by which the two species are clearly separated, is becoming the diagnostic standard for black yeasts. Most strains of E. oligosperma are strongly yeast-like and hence are not morphologically distinctive. The few hyphal annellidic cells found are stouter than those found in E. jeanselmei when it produces regular, rocket-shaped conidiogenous cells. The annellated zone in E. oligosperma is short and irregular, while that of E. jeanselmei is pronounced and tapering, with annellations that are nearly invisible in light microscopy (9) (Fig. 5). E. nishimurae is morphologically identical to E. oligosperma and also produces large chlamydospores; it is unable to assimilate erythritol (43), unlike E. oligosperma and E. jeanselmei (8, 38).

FIG. 5.

E. jeanselmei CBS 507.90. Shown are characteristic rocket-shaped conidiogenous cells on a mature thallus. Bar = 10 μm.

E. oligosperma contained strain CBS 725.88, originating from a fatal cerebral infection in an otherwise healthy woman (38); CBS 463.80 from a human keratitis; UTHSC 01-1637 from an olecranon bursitis (2); CBS 835.95 from a human mycetoma (29); and some additional clinical isolates (Table 1). The environmental strains clustering in this group mostly originated from low-nutrient or sugary substrates, such as honey or silicone, or were found on damp surfaces on inert material in saunas and swimming pools (Table 1). Nucci et al. (30, 31) reported a nosocomial outbreak of 19 cases of fungemia caused by E. jeanselmei and originating from contaminated hospital water. All of the strains were shown to be strictly identical. Their reference strain, UTHSC 98-811, was shown to be E. oligosperma by ITS sequencing. There is an apparent link between waterborne contamination by this species and opportunistic infection in humans. The combination of clinical isolates and isolates from low-nutrient or slightly osmotic substrates is known to occur for the black yeast E. dermatitidis (12, 21), as well as for E. spinifera (11). This phenomenon has not been explained, and virulence testing is recommended for the environmental isolates. The Phialophora-like, disinfectant-refractory strains reported by Phillips et al. (33) from hospital water tubes belong to the as-yet-undescribed species of cluster 8 (Fig. 2).

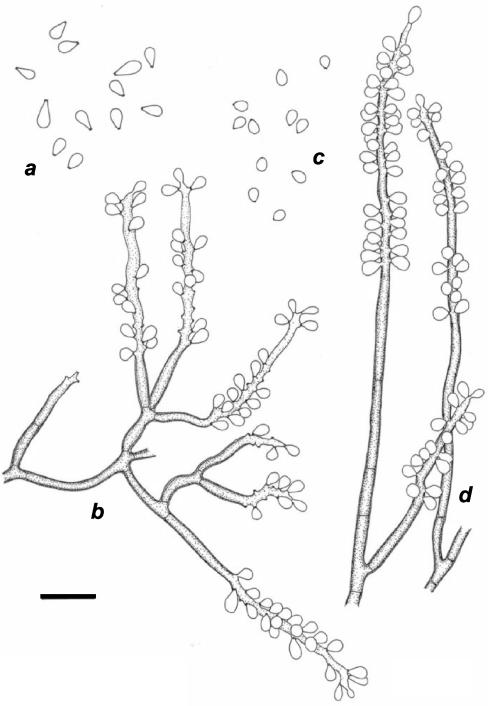

Ramichloridium basitonum.

By 18S rDNA phylogeny, strain CBS 101460 was found to be located within the E. spinifera clade (Fig. 1). On the basis of ITS sequence data, the strain was close to E. jeanselmei (Fig. 2). The strain was monomorphic with a basitonously branched system of dark-brown conidiophores densely packed with sympodial conidia in the apical part (Fig. 6). Originally, the strain was reported as the cause of a human phaeohyphomycosis under the name “Geniculosporium sp.” (37). However, Geniculosporium is an anamorph genus of Xylariales and hence is located at a large phylogenetic and taxonomic distance from the Chaetothyriales. The order Xylariales exclusively contains species occurring on wood, while Chaetothyriales contains both pathogens and environmental species. Morphologically, Xylariaceous anamorphs are characterized by having rhexolytic conidial secession, thus leaving distinct frills at the base of the conidium, as well as on the conidiophore. CBS 101460 morphologically and phylogenetically fits the Chaetothyriaceous genus Ramichloridium; its pathogenicity also fits this overall picture. The species is formally introduced below as a new taxon. It differs from R. anceps (ex-neotype strain CBS 181.65) by its basitonously branched conidiophores and triangular conidia (Fig. 7). R. anceps is found far outside the E. spinifera clade (Fig. 1); its ITS sequence could not be aligned with confidence and was omitted from further analysis. Apparently, the Ramichloridium type of conidial apparatus is polyphyletic.

FIG. 6.

(a and b) R. basitonum CBS 101460. Shown are the conidia (a) and conidial apparatus (b). (c and d) R. anceps CBS 181.65. Shown are the conidia (c) and conidial apparatus (d). Bar = 10 μm.

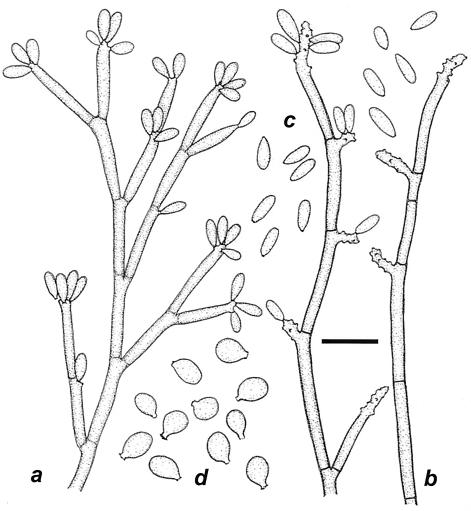

FIG. 7.

R. similis CBS 111763. (a) Immature conidial apparatus; (b) differentiated conidiogenous cells with sympodial conidia; (c) conidia; (d) germinating cells with annellated zones. Bar = 10 μm.

R. similis.

Based on SSU rDNA data, the position of CBS 11176 (HC-1) (M. A. Resende, R. B. Caligiorne, C. R. Aguilar, and M. M. Gontijo, Abstr. 14th Congr. Int. Soc. Human Anim. Mycol., p. 274, 2000) is within the E. spinifera clade (Fig. 1). By ITS sequence data, it is found to be close to E. jeanselmei, but it has preponderantly sympodial conidiogenesis. It has a profusely branched conidial apparatus of the same texture and pale-brown pigmentation as its mycelium. This feature is the hallmark of Rhinocladiella, and the species is therefore morphologically attributed to that genus. The morphologically indistinguishable species R. atrovirens is found at a large SSU distance (Fig. 1), and its ITS sequences could not be aligned (data not shown). The former type strain CBS 317.33 is not consistent with Rhinocladiella, as it consists of a Phialophora-like fungus that differs from the holotype specimen (15). Thus, Rhinocladiella is also a solely morphologically defined polyphyletic genus. The above-mentioned data show that striking polyphyly is also observed in Exophiala (E. spinifera versus E. attenuata) and in Ramichloridium (R. anceps versus R. basitonum). In the order Chaetothyriales, genera are maintained on the basis of morphology for practical reasons (15). The ITS rDNA sequence of Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, a rare agent of human chromoblastomycosis (1), could not be aligned with confidence. Schell et al. (36) regarded Ramichloridium cerophilum, originating from leaf litter (24), as a synonym of R. aquaspersa, but its ITS sequence could not confidently be aligned (data not shown). Only few strains of R. aquaspersa are known (Table 1), and therefore it is difficult to speculate on its pathogenic potential. The former type strain was described as the etiologic agent in a human chromoblastomycotic lesion (1).

Taxonomy.

Table 2 shows an approximate phenetic key to the species of the E. spinifera clade.

TABLE 2.

Approximate phenetic key to the species of the E. spinifera cladea

| No. | Characteristic | ITS cluster |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Conidiogenesis preponderantly annellidic | 2 |

| 1b | Conidiogenesis preponderantly sympodial | 9 |

| 2a | Erect, multicellular conidiophores present that are darker than the supporting mycelium | 3 |

| 2b | Erect, dark, multicellular conidiophores absent | 4 |

| 3a | Annellated zones long with clearly visible, frilled annellations | E. spinifera |

| 3b | Annellated zones inconspicuous, degenerate | E. attenuata |

| 4a | Mature conidiogenous cells rocket shaped, slightly darker than the supporting hyphae, with regular, tapering annellated zone | E. jeanselmei |

| 4b | Mature conidiogenous cells otherwise remaining concolorous with supporting hyphae | 5 |

| 5a | Conidiogenous cells intercalary, conidia being produced from repent hyphae | E. lecanii-corni |

| 5b | Conidiogenous cells intercalary and lateral, the latter being elongate, flask to rocket shaped | 6 |

| 6a | Budding cells only; hyphal fragments mostly without marked conidiation | E. exophialae |

| 6b | Hyphae producing conidia are preponderant | 7 |

| 7a | Annellated zones minute, tooth shaped | E. heteromorpha |

| 7b | Annellated zones having the appearance of inconspicuous flat scars | 8 |

| 8a | Large chlamydospore-like cells present | E. nishimurae |

| 8b | Chlamydospore-like cells absent | E. oligosperma |

| 9a | Dark-brown, thick-walled conidiophores present | 10 |

| 9b | Conidiophores only slightly darker than the remaining mycelium | 11 |

| 10a | Conidiophores unbranched | R. anceps |

| 10b | Conidiophores composing a basitously branched system | R. basitonum |

| 11a | Conidia broadly ellipsoidal, pale brown | R. aquaspersa |

| 11b | Conidia cylindrical, hyaline | R. atrovirens; R. similis |

For reliable species identification, ITS rDNA sequencing remains necessary.

(i) Exophiala oligosperma Calendron ex de Hoog et Tintelnot, sp. nov.

(Melanchlenus oligospermus Calendron [reference 4, without Latin diagnosis]. Exophiala sp. [38].) Exophiala conidiophoris cylindricis, annellatis aut globis et catenatis. Conidia obovoidea, subhyalina. Ab Exophialae jeanselmei differt conidiophoris majoris. Typus (vivus et exsiccatus) CBS 725.88 in herbarium CBS preservatur (Fig. 4).

Colonies on PDA at 28°C after 10 days are restricted; they are initially slimy and slightly wrinkled at the center, later developing floccose aerial mycelium, and olivaceous grey to brownish black with olivaceous black reverse. Colonies on malt extract agar are velvety, olivaceous grey, and dry, mostly with an insignificant yeast phase. No diffusible pigment is produced on any medium. Budding cells are abundant, pale olivaceous, broadly ellipsoidal, 3 by 2.5 μm, and without capsule in India ink, often inflating and developing into broadly ellipsoidal brown germinating cells, ∼ 6 by 5 μm, that often bear a short, irregular annellated zone. Hyphae are pale olivaceous to brown, somewhat inflated, 1.5 to 3.2 μm wide, and irregularly septate every 20 to 40 μm. Conidiogenous cells mostly arise at acute angles as part of a slightly differentiated conidial apparatus, also arising at right angles from creeping hyphae. Conidial branches are the same color as the hyphae or only slightly darker and one to three celled; the ultimate cells have rocket-shaped or cylindrical tapering ends with a flaring, irregular annellated zone. Conidia adhere in small groups and are subhyaline, obovoidal, and 3 to 5 by 2.2 to 3.2 μm. Spherical, subhyaline chlamydospores up to 13 μm in diameter may be present. The teleomorph is unknown.

Type (living and dried): CBS 725.88, isolated from fatal cerebral mycosis with hyphae and circular grains in tissue in an otherwise healthy 45-year-old female, Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, 1988 (38).

(ii) Rhinocladiella similis de Hoog et Caligiorne, sp. nov.

Rhinocladiella conidiophoris sympodialis bene ramosis, denticulatis. Conidia elongata, non-catenata. Typus (vivus et exsiccatus) CBS 111763 in herbarium CBS preservatur (Fig. 7).

Colonies on PDA at 28°C after 10 days are restricted, mostly dry or initially with some black slime at the centre, velvety, and olivaceous grey with olivaceous black reverse. No diffusible pigment is produced on any medium. Budding cells are abundant, pale olivaceous, broadly ellipsoidal, ∼5 by 3 μm, and without capsule in India ink, often inflating and developing into broadly ellipsoidal brown germinating cells, ∼5 by 4 μm, that often bear a clearly discernible truncate extension which bears a very short annellated zone. Hyphae are pale olivaceous to brown, evenly 1.5 μm wide, and regularly septate every 20 to 40 μm. Conidiogenous cells arise at acute angles in a profusely branched conidial apparatus which is brown, somewhat darker than the sterile hyphae; conidiogeneous cells are cylindrical, 12 to 20 by 2 μm apically, with an elongating sympodial part bearing conidia on small denticles mainly at the apices of the cells. Conidia are subhyaline, noncatenate, cylindrical, narrowed toward the base, and 4 to 7 by 1.5 μm, with a small but clearly visible scar. Chlamydospores are absent. The teleomorph is unknown.

Type (living and dried): CBS 111763 = DH 11329 = HC-1, isolated from chronic cutaneous ulcer with hyphae in tissue in a 72-year-old Caucasian male, Minas Gerais, Brazil (Resende et al., Abstr. 14th ISHAM).

(iii) Ramichloridium basitonum de Hoog, sp. nov.

(Geniculosporium sp. [37].) Ramichloridium monomorphum, conidiophoris basitonis ramosis. Ab Ramichloridii anceps differt conidiis trangularis. Typus (vivus et exsiccatus) CBS 101460 in herbarium CBS preservatur (Fig. 6).

Colonies on PDA at 28°C after 10 days are smooth, compact, and slightly elevated at the center, flat toward margin, locally with some submerged mycelium, and olivaceous black with black reverse. No diffusible pigment is produced. Budding and germinating cells are absent. Hyphae are regular, rather thick walled, olivaceous brown, ∼2 μm wide, and septate every 15 to 20 μm. The conidial apparatus is profusely branched with flexuose cells arising at acute angles, the lower cells often being shorter than the ultimate ones and concolourous with the hyphae. Conidiogenous cells are cylindrical, with the apical part of variable length, producing numerous conidia in sympodial sequence; denticles are truncate, with a slightly darkened scar without a hilum. Conidia are hyaline, smooth walled and thin walled, triangular with a rounded apex, and 3.5 to 4.5 by 2.2 μm with a clearly discernible basal scar. Chlamydospores are absent. The teleomorph is unknown.

Type (living and dried): CBS 101460, isolated from asymptomatic subcutaneous nodule histopathologically with formation of hyphae in tissue in otherwise healthy 70-year-old timber mill worker, Hamamatsu, Japan, 1994 (37).

Etymology: named after basitonous branching system, i.e., with branches inserted in the lower parts of the main conidiophore.

(iv) Exophiala heteromorpha (Nannf.) de Hoog et Haase, comb. nov.

[Trichosporium heteromorphum Nannf. (25a) (basionym) = Margarinomyces heteromorpha (Nannf.) Mangenot (20a) = Phialophora heteromorpha (Nannf.) Wang (46) = Exophiala jeanselmei (Langer.) McGinnis et Padhye var. heteromorpha (Nannf.) (7) = Wangiella heteromorpha (Nannf.) McKemy (25).]

(v) Exophiala exophialae (de Hoog) de Hoog, comb. nov.

[Phaeococcus exophialae (7) (basionym) = Phaeococcomyces exophialae (de Hoog) (12a) (change made because of preexisting generic name Phaeococcus Borzi 1892—brown algae).]

Acknowledgments

The curator of the IFM culture collection (Chiba, Japan) is acknowledged for sending strains. We thank K. F. Luijsterburg and K. Luyk for technical assistance, R. C. Summerbell for comments on the text, and A. Aptroot for preparing the Latin diagnoses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borelli, D. 1972. Acrotheca aquaspersa nova species agente de Cromomicosis. Acta Cient. Venez. 23:193-196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bossler, A. D., S. S. Richter, A. J. Chavez, S. A. Vogelgesang, D. A. Sutton, A. M. Grooters, M. G. Rinaldi, G. S. de Hoog, and M. A. Pfaller. 2003. Exophiala oligosperma causing olecranon bursitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 4779-4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Calendron, A. 1953. Melanchlenus eumetabolus n. sp. Rev. Mycol. Suppl. Colon. 17:190-196. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calendron, A. 1953. Multiconjugaisons chez les champignons levuriformes à pigment noir. C. R. Acad. Sci. 236:1598-1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calendron, A. 1953-1954. Étude bibliographique des champignons levuriformes à pigment noir. Ann. École Nat. Agric. Rennes 15:76-87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox, H. H. J., J. H. M. Houtman, H. J. Doddema, and W. Harder. 1993. Growth of the black yeast Exophiala jeanselmei on styrene and styrene-related compounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39:372-376. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Hoog, G. S. 1977. Rhinocladiella and allied genera. Stud. Mycol. 15:1-144. [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Hoog, G. S., A. H. G. Gerrits van den Ende, J. M. J. Uijthof, and W. A. Untereiner. 1995. Nutritional physiology of type isolates of currently accepted species of Exophiala and Phaeococcomyces. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 68:43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Hoog, G. S., J. Guarro, J. Gené, and M. J. Figueras. 2000. Atlas of clinical fungi, 2nd ed. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- 10.De Hoog, G. S., J. M. J. Uijthof, A. H. G. Gerrits van den Ende, M. J. Figge, and X. O. Weenink. 1997. Comparative rDNA diversity in medically significant fungi. Microbiol. Cult. Collect. 13:39-48. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Hoog, G. S., N. Poonwan, and A. H. G. Gerrits van den Ende. 1999. Taxonomy of Exophiala spinifera and its relationship to E. jeanselmei. Stud. Mycol. 43:133-142. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Hoog, G. S., and G. Haase. 1993. Nutritional physiology and selective isolation of Exophiala dermatitidis. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 64:17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.de Hoog, G. S. 1979. Nomenclatural notes on some black yeast-like Hyphomycetes. Taxon 28:347-348.

- 13.De Rijk, P., and R. De Wachter. 1993. DCSE v. 2.54, an interactive tool for sequence alignment and secondary structure research. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 9:735-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerrits van den Ende, A. H. G., and G. S. De Hoog. 1999. Variability and molecular diagnostics of the neurotropic species Cladophialophora bantiana. Stud. Mycol. 43:151-162. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haase, G., L. Sonntag, B. Melzer-Krick, and G. S. De Hoog. 1999. Phylogenetic inference by SSU-gene analysis of members of the Herpotrichielllaceae with special reference to human pathogenic species. Stud. Mycol. 43:80-97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jobst, J., K. King, and V. Hemleben. 1998. Molecular evolution of the internal transcribed spacers (ITS1 and ITS2) and phylogenetic relationships among species of the family Cucurbitaceae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 9:204-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawasaki, M., H. Ishizaki, T. Matsumoto, T. Matsuda, K. Nishimura, and M. Miyaji. 1999. Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Exophiala jeanselmei var. lecanii-corni and Exophiala castellanii. Mycopathologia 146:75-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawasaki, M., H. Ishizaki, K. Nishimura, and M. Miyaji. 1990. Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Exophiala jeanselmei and Exophiala dermatitidis. Mycopathologia 110:107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langeron, M. 1928. Mycétome à Torula jeanselmei Langeron, 1928. Nouveau type de mycétome à grains noirs. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 6:385-403. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieckfeldt, E., and K. A. Seifert. 2000. An evaluation of the use of ITS sequences in the taxonomy of the Hypocreales. Stud. Mycol. 45:35-44. [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Mangenot, F. 1952. Recherches sur les champignons de certains bols en décomposition. Lib. Gén. Enseign., Paris, France.

- 21.Matos, T., G. S. De Hoog, A. G. De Boer, I. De Crom, and G. Haase. 2002. High prevalence of the neurotrope Exophiala dermatitidis and related oligotrophic black yeasts in sauna facilities. Mycoses 45:373-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuda, M., W. Naka, S. Tajima, T. Harada, T. Nishikawa, L. Kaufman, and P. Standard. 1989. Deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization studies of Exophiala dermatitidis and Exophiala jeanselmei. Microbiol. Immunol. 33:631-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto, T., A. A. Padhye, L. Ajello, and P. G. Standard. 1984. Critical review of human isolates of Wangiella dermatitidis. Mycologia 76:232-249. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsushima, T. 1975. Icones fungorum a Matushima lectorum. Privately printed, Kobe, Japan.

- 25.McKemy, J. M., S. O. Rogers, and C. J. K. Wang. 1999. Emendation of the genus Wangiella and a new combination, W. heteromorpha. Mycologia 91:200-205. [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Melin, E., and J. A. Nannfeldt. 1934. Researches into the blueing of ground wood-pulp. Svenska Skogsvför. Tidskr. 32:397-616.

- 26.Middelhoven, W. J., G. S. De Hoog, and S. Notermans. 1989. Carbon assimilation and extracellular antigens of some yeast-like fungi. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 55:165-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray, I. G., G. E. Dunkerley, and K. E. A. Hughes. 1963. A case of Madura foot caused by Phialophora jeanselmei. Sabouraudia 3:175-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naka, W., T. Harada, T. Nishikawa, and R. Fukushiro. 1986. A case of chromoblastomycosis with special reference to the mycology of the isolated Exophiala jeanselmei. Mykosen 29:445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neumeister, B., T. M. Zollner, D. Krieger, W. Sterry, and R. Marre. 1995. Mycetoma due to Exophiala jeanselmei and Mycobacterium chelonae in a 73-year-old man with idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia. Mycoses 38:271-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nucci, M., T. Akiti, G. Barreiros, F. Silveira, S. G. Revankar, B. L. Wickes, D. A. Sutton, and T. F. Patterson. 2002. Nosocomial outbreak of Exophiala jeanselmei fungemia associated with contamination of hospital water. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:1475-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nucci, M., T. Akiti, G. Barreiros, F. Silveira, S. G. Revankar, D. A. Sutton, and T. F. Patterson. 2001. Nosocomial fungemia due to Exophiala jeanselmei var. jeanselmei and a Rhinocladiella species: newly described causes of bloodstream infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:514-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Donnell, K., and E. Cigelnik. 1997. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the genus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 7:103-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips, G., H. McEwan, I. McKay, G. Crowe, and J. McBeath. 1998. Black pigmented fungi in the water pipe-work supplying endoscope washer disinfectors. J. Hosp. Infect. 40:250-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritland, C. E., K. Ritland, and N. A. Strauss. 1993. Variation in the ribosomal internal transcribed spacers (ITS1 and ITS2) among eight taxa of the Mimulus guttatus species complex. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10:1273-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders, I. R., M. Alt, K. Groppe, T. Boller, and A. Wiemken. 1995. Identification of ribosomal DNA polymorphisms among and within spores of the Glomales: application to studies on the genetic diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. New Phytol. 130:419-427. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schell, W. A., M. R. McGinnis, and D. Borelli. 1983. Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, a new combination for Acrotheca aquaspersa. Mycotaxon 17:341-348. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki, Y., S. Udagawa, H. Wakita, N. Yamada, H. Ichikawa, F. Furukawa, and M. Takigawa. 1998. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by Geniculosporium species; a new fungal pathogen. Br. J. Dermatol. 138:346-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tintelnot, K., G. S. De Hoog, E. Thomas, W.-I. Steudel, K. Huebner, and H. P. R. Seeliger. 1991. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis caused by an Exophiala species. Mycoses 34:239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Untereiner, W. A. 2000. Capronia and its anamorphs: exploring the value of morphological and molecular characters in the systematics of the Herpotrichiellaceae. Stud. Mycol. 45:141-149. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Untereiner, W. A., A. H. G. Gerrits van den Ende, and G. S. De Hoog. 1999. Nutritional physiology of species of Capronia.. Stud. Mycol. 43:98-106. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van de Peer, Y., and R. De Wachter. 1994. Treecon for Windows: a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the Microsoft Windows environment. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 10:569-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Virtudazo, E. V., H. Nakamura, and M. Kakishima. 2001. Ribosomal DNA-ITS sequence polymorphism in the sugarcane rust, Puccinia kuehnii. Mycoscience 42:447-453. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vitale, R. G., and G. S. De Hoog. 2002. Molecular diversity, new species and antifungal susceptibilities in the Exophiala spinifera clade. Med. Mycol. 40:545-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, C. J. K., and R. A. Zabel. 1990. Identification manual for fungi from utility poles in the Eastern United States. Allen Press, Lawrence, Kans.

- 45.Wang, L., K. Yokoyama, M. Miyaji, and K. Nishimura. 2001. Identification, classification, and phylogeny of the pathogenic species Exophiala jeanselmei and related species by mitochondrial cytochrome b gene analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4462-4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, C. J. K. 1964. Studies on Trichosporium heteromorphum Nannfeldt. Can. J. Bot. 42:1011-1016.