Abstract

A 62-year-old male with a history of Wegener's granulomatosis and immunosuppressive therapy presented with chronic olecranon bursitis. A black velvety mould with brown septate hyphae and tapered annellides was isolated from a left elbow bursa aspirate and was identified as an Exophiala species. Internal transcribed sequence rRNA sequencing showed the isolate to be identical to Exophiala oligosperma. The patient was successfully treated with aspiration and intrabursal amphotericin B.

Exophiala species are dematiaceous, or dark-pigmented, dimorphic hyphomycetes that are found at low density in relatively extreme microniches, such as oligotrophic waters or preservative-treated wood. The species most commonly involved in human infection are Exophiala jeanselmei complex members, Exophiala spinifera, and Exophiala dermatitidis, with other species at low frequency (4, 6, 28). They are generally associated with phaeohyphomycosis, which encompasses a heterogeneous group of infections that are histologically defined by the presence of yeast-like or hyphal forms of the fungus in superficial subcutaneous locations or disseminated systemic disease. The increased detection of Exophiala species as agents of human disease is also believed to be related to the increased number of immunocompromised hosts (2, 10, 24, 26, 27). We report an unusual case of olecranon bursitis attributed to the newly recognized species Exophiala oligosperma (7).

(Presented at the 102nd General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, 21 May 2002 [abstract F-80].)

Case report.

A 62-year-old male with Wegener's granulomatosis presented to the University of Iowa rheumatology clinic in July 2001 with chronic painless left elbow swelling. The patient was known to rest his elbows on a sink while irrigating his sinuses twice daily for chronic sinusitis. The elbow was not warm or erythematous. Raised scabbed areas were observed on the skin over the olecranon process that had been present for at least 8 months. The patient exhibited no other signs of infection, and his white blood cell count was within normal limits. The patient's vasculitis had been treated with prednisone, 20 mg daily, which was tapered to 5 mg every other day, and cyclophosphamide, 100 mg daily, for several months. The olecranon bursa was aspirated, and 15 ml of fluid was removed.

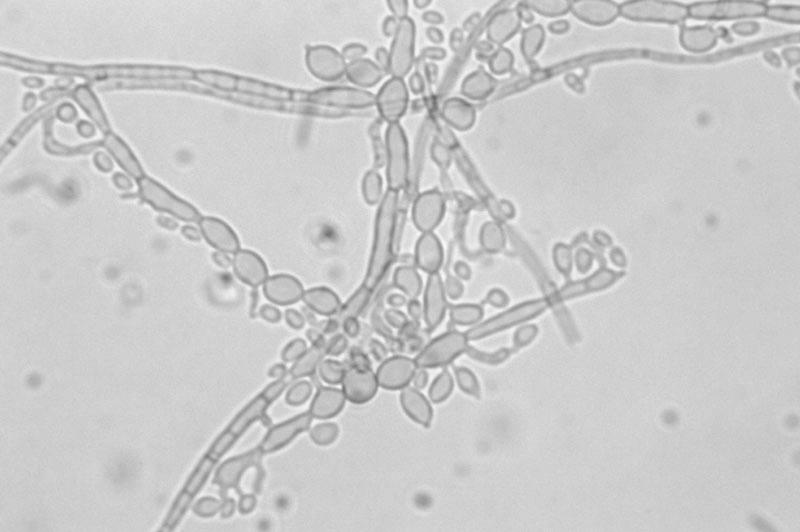

No organisms were seen on Gram or calcofluor white stains. Fungal cultures on potato dextrose agar initially grew yeast-like colonies that developed into an olivaceous black velvety mould with aerial hyphae and a black reverse (Fig. 1). Microscopically, the hyphae were septate and pale brown. Conidia were formed in small clusters both from intercalary loci along undifferentiated hyphae and from tapered annellidic conidiogenous cells (Fig. 2), features characteristic of Exophiala species. Two subsequent aspirations from the left olecranon bursa ∼1 month apart (3 and 7 weeks after the initial aspiration) also grew Exophiala species.

FIG. 1.

Growth of E. oligosperma on potato flake agar for 16 days at 25°C.

FIG. 2.

True hyphae (top), inflated cells of pseudohyphae (left), and annelloconidia from prominent intercalary conidiogenous loci (right) of E. oligosperma.

The isolate was submitted for species identification to the Fungus Testing Laboratory, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and accessioned into their stock collection as UTHSC 01-1637. Subcultures onto potato flake agar incubated at 25°C produced small dark yeast-like colonies within 6 days. With extended incubation, the colonies became more filamentous, and at 16 days they were brown pigmented and measured ∼18 mm in diameter. Temperature studies on potato flake agar indicated growth at 25 and 30°C but no growth at 35°C. The isolate was positive for nitrate assimilation and grew on media containing cycloheximide. Microscopically, single-celled, small apiculate annelloconidia (1 to 1.5 by 1.5 to 2.5 μm) were produced from relatively short, somewhat inflated annellides, as well as from intercalary loci. The yeast cells were larger (4 by 5.5 to 8 μm), somewhat inflated like those of Exophiala pisciphila, and had prominent annellated projections. As this isolate did not appear to represent any of the known Exophiala species, it was referred to A. Grooters for sequencing.

A segment of the nuclear rRNA gene that included the entire internal transcribed sequence 1 (ITS1) region and portions of the 18S and 5.8S subunits was amplified using primers EXO1 (5′-CTCAGAGCCGGAAACTTGGTC-3′) and EXO2 (5′-CCGCCGTCATTGTCTTTGG-3′), which had been designed by one of the authors (A.M.G.) for amplification of Exophiala species. The resultant products were sequenced from both the 5′ and 3′ ends with a dye-labeled terminator kit and automated sequencer. The sequence of this isolate, GenBank accession number AY231163, was compared with those of other isolates recently described and clustered by G. S. de Hoog et al. (7). The isolate was found to be strictly identical to the newly defined type strain E. oligosperma Calandron ex de Hoog et Tintelnot (7, 29).

Susceptibility testing.

Antifungal susceptibility was determined in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory at the University of Iowa using a broth microdilution assay according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines (22). The MIC endpoints were read visually after 48 h of incubation at 35°C. The MICs of flucytosine, itraconazole, and voriconazole were defined at ∼50% inhibition. The amphotericin B endpoint was read at complete inhibition of growth. Quality control testing was performed with Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019. The isolate showed in vitro susceptibility to flucytosine, itraconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B, with corresponding MICs of 4.0, 0.25, 0.12, and 1.0 μg/ml, respectively. Even though NCCLS antimicrobial susceptibility breakpoints have not been set for these fungal species, the low MICs suggest that the isolate would be susceptible to all of these antifungal agents.

Therapy was initiated 2 months after the initial positive culture and consisted of weekly aspiration of bursal fluid and intrabursal injection of 1 (initial dose) or 2 mg of amphotericin B once a week for 4 weeks (total dose, 7 mg). The patient initially received a test dose of 0.1 mg of amphotericin B with significant pain. Thereafter, the patient received 1% lidocaine 10 to 30 min before the amphotericin injection. Calcofluor stains and cultures of fluid aspirated prior to the third injection and 11 weeks after the final injection were negative for fungal organisms. Cool swelling of the left olecranon bursa continued to be noted 5 months after completion of therapy, but complete resolution of the bursitis was documented 10 months after the final amphotericin injection.

Discussion.

This report describes the case of a rare infection of the olecranon bursa by the newly recognized species E. oligosperma. Twenty-three isolates of E. oligosperma have been identified, and the majority are from environmental sources (honey, swimming pool, and soil) (7). Of the seven other human E. oligosperma isolates, three were originally considered E. jeanselmei, one was named Rhinocladiella sp., and the remaining three were not given a species designation (7). Exophiala species are dematiaceous hyphomycetes exhibiting a black yeast synanamorph and conidial production predominantly via annellidic conidiogenous cells. They are related to the phaeoid moulds, including Fonsecaea, Cladophialophora, Phialophora, Rhinocladiella, and Ramichloridium. E. jeanselmei was the first species identified, from a mycetoma of the foot in 1928 by Jeanselme on Martinique Island (20, 26), and it was given the name Torula jeanselmei by Langeron. The Exophiala genus was erected by Carmichael in 1966, describing an aquatic hyphomycete of trout fry, Exophiala salmonis (1). In 1977, after many changes in nomenclature, T. jeanselmei was transferred to the Exophiala genus (19) based on its conidiogenesis, which has remained a defining criterion for the genus. The type strain of E. oligosperma, Melanchlenus oligospermus, was isolated by Calendron in 1953 and is defined by molecular methods in this issue (7).

Species identification has historically involved separation based on morphological and biochemical assimilative properties (3, 5). The colony morphology of E. oligosperma most closely resembles those of E. jeanselmei and E. spinifera, with an olivaceous black color, a black reverse, and a velvety appearance due to the aerial mycelium (28). Other species, such as E. dermatitidis, have a colony morphology that is flat with a scar-like annellated zone of brown pigment diffused into the agar, while E. pisciphila has a dry and hairy appearance. Microscopically, annelloconidiation is a defining morphological feature of Exophiala species. Septate hyphae form tapered tubes, or annellides, that eventually bear ovoid conidiogenous daughter cells (annelloconidia) from their ends (Fig. 2). The annelloconidia are usually one celled and can be found at the tapered ends of the annellides or along the sides of the hyphae in small clusters of cells (28). Some of the biochemical characteristics that separate E. oligosperma from E. jeanselmei, though tested with a limited number of isolates, are the ability to utilize xylose and creatinine and the absence of growth with lactose, inositol, or citrate (29). E. oligosperma differs from E. dermatitidis in that it assimilates nitrate, nitrite, creatinine, and creatine but not inositol. Physiologically, E. oligosperma most closely resembles E. pisciphila, differing only in its inability to utilize lactose and inositol. More recently, molecular techniques have been employed for species identification and genus comparison, including restriction fragment length polymorphism (32), random amplified polymorphic DNA (31), and DNA sequencing. Sequencing of rRNA genes, ITS sequences, and small-subunit genes has proven particularly robust because of the ability to show relatedness of the dematiaceous fungi and still separate the individual species at a fundamental level (4, 12, 33). The rRNA ITS results were used to confirm the identity of this isolate as E. oligosperma (7).

Exophiala species are most commonly isolated clinically from cutaneous lesions or subcutaneous nodules following traumatic inoculation or contamination of a wound or surgical site (8, 26). Phaeohyphomycosis, or the presence of pigmented yeast-like or hyphal forms in tissue, is the most common presentation. However, some species occasionally appear as thick-walled muriform cells with intersecting cross walls (sclerotic bodies) in superficial or subcutaneous nodules, referred to as chromoblastomycosis. Mycetoma is another form of infection by dematiaceous fungi defined by the presence of black mycotic granules, usually with subcutaneous tumefaction.

Exophiala species have been isolated from several human tissues besides superficial and subcutaneous sites, including ophthalmologic, cardiac, bone, and central nervous system tissues (14, 26, 31). Pulmonary infection is associated with inhalation of the organism (18), and the organism has been isolated from the sputa of patients with cystic fibrosis (11, 23). Reports of central nervous system infection have been published particularly for E. dermatitidis (13, 30) and for the Exophiala species now recognized as E. oligosperma (7, 29). Review of the literature reveals only one report of isolation of an Exophiala species, E. jeanselmei, from a joint (knee) (A. J. Roncoroni and J. Smayevsky, Letter, Ann. Intern. Med. 108:773, 1988). Roncoroni and Smayevsky describe a complex case of E. jeanselmei infection of the right knee synovium and of a ventricular septal defect patch in a patient who presented with multiple bouts of septic fungal emboli to the lungs and heart. His treatment with up to 3,000 mg of amphotericin B and 200 mg of ketoconazole/day for over a year was not successful in eradicating the fungus. Postmortem examination revealed an abscess of the interventricular septum and multiple pulmonary emboli with mycotic granulomas in the parenchyma. The tissue origin of the infection could not be determined, as initial knee aspirates failed to grow any fungus and no direct trauma to the knee was ever reported.

The rise in recovery of and recognition of infections by Exophiala and other dematiaceous fungi appears to parallel the increase in the number of immunocompromised patients. Multiple reports describe the infection of organ transplant recipients on high-dose steroids and other immunosuppressive agents by Exophiala species (9, 25, 26, 27). In addition, partial defects in cell-mediated immunity have been associated with both human infection and infection in animal models (16, 17).

Most reports of curative therapy describe the use of surgical debridement and long-term antifungal medication and illustrate the difficulty in treating these types of fungal infections. Long-term therapy that is interrupted or prematurely terminated raises the concern for developing antifungal resistance. Meletiadis et al. reported that 11 clinical isolates of E. spinifera, E. dermatitidis, and Exophiala castellani were susceptible to miconazole, terbinafine, itraconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B, with MICs at which 90% of isolates were inhibited ranging from 0.125 to 1.0 μg/ml (21). They found that terbinafine was the most active drug against all of the isolates. Others have reported susceptibility to commonly used antifungal agents as well (9, 18; D. Whittle and I. S. Kominos, Letter, Clin. Infect. Dis. 21:1068, 1995). However, one report by Rath et al. (23) found that the 30% inhibitory concentration (the concentration required to reduce growth to 30% of the growth control) for 11 strains of E. dermatitidis indicated susceptibility to amphotericin B, ketoconazole, and itraconazole but not to fluconazole or flucytosine. Another report by Kotylo et al. (15) described flucytosine and amphotericin B resistance in E. spinifera. At present, it appears that the difficulty of infection eradication is not likely to be due to antifungal resistance as measured in vitro. Notably, the isolate in the present case was quite susceptible to all agents tested, and the infection was managed by aspiration and local instillation of amphotericin B into the bursa.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number for the E. oligosperma nuclear rRNA gene segment reported in this paper is AY231163.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carmichael, J. W. 1966. Cerebral mycetoma of trout due to a Phialophora-like fungus. Sabouraudia 5:120-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clancy, C. J., J. R. Wingard, and M. H. Nguyen. 2000. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in transplant recipients: review of the literature and demonstration of in vitro synergy between antifungal agents. Med. Mycol. 38:169-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Hoog, G. S., A. H. G. Gerrits van den Ende, J. M. J. Uijthof, and W. A. Untereiner. 1995. Nutritional physiology of type isolates of currently accepted species of Exophiala and Phaeococcomyces. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 68:43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Hoog, G. S., B. Bowman, Y. Graser, G. Haase, M. el Fari, A. H. G. Gerrits van den Ende, B. Melzer-Kricks, and W. A Untereiner. 1998. Molecular phylogeny and taxonomy of medically important fungi. Med. Mycol. 36:52-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Hoog, G. S., N. Poonwan, and A. H. G. Gerrits van den Ende. 1999. Taxonomy of Exophiala spinifera and its relationship to E. jeanselmei. Stud. Mycol. 43:133-142. [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Hoog, G. S., J. Guarro, M. J. Figueras, and J. Gené. 2000. Atlas of clinical fungi, 2nd ed. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- 7.de Hoog, G. S., V. Vicente, R. B. Caligiorne, S. Kantarcioglu, K. Tintelnot, A. H. G. Gerrits van den Ende, and G. Haase. 2003. Species diversity and polymorphism in the Exophiala spinifera clade containing opportunistic black yeast-like fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4767-4778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Fothergill, A. W. 1996. Identification of dematiaceous fungi and their role in human disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22:S179-S184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gold, W. L., H. Vellend, I. E. Salit, O. Campbell, R. Summerbell, M. Rinaldi, and A. E. Simor. 1994. Successful treatment of systemic and local infections due to Exophiala species. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19:339-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groll, A. H., and T. J. Walsh. 2001. Uncommon opportunistic fungi: new nosocomial threats. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7:8-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haase, G., H. Skopnik, T. Groten, G. Kusenbach, and H.-G. Posselt. 1991. Long-term fungal cultures from sputum of patients with cystic fibrosis. Mycoses 34:373-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haase, G., L. Sonntag, Y. van de Peer, J. M. J. Uijthof, A. Podbielski, and B. Melzer-Krick. 1995. Phylogenetic analysis of ten black yeast species using nuclear small subunit rRNA gene sequences. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 68:19-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jotsinkasa, V., H. S. Nielsen, and N. F. Conant. 1970. Phialophora dermatitidis, its morphology and biology. Sabouraudia 8:98-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenney, R. T., K. J. Kwon-Chung, A. T. Waytes, D. A. Melnick, H. I. Pass, M. J. Merino, and J. I. Gallin. 1992. Successful treatment of systemic Exophiala dermatitidis infection in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotylo, P. K., K. S. Israel, J. S. Cohen, and M. S. Bartlett. 1989. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis of the finger caused by Exophiala spinifera. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 91:624-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahgoub, E. S., S. A. Bumaa, and A. M. El Hassan. 1977. Immunological status of mycetoma patients. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. Filiales 70:48-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahgoub, E. S. 1978. Experimental infection of athymic nude New Zealand mice, nu nu strain with mycetoma agents. Sabouraudia 16:211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manian, F. A., and M. J. Brischetto. 1993. Pulmonary infection due to Exophiala jeanselmei: successful treatment with ketoconazole. Clin. Infect. Dis. 16:445-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGinnis, M. R. 1977. Wangiella, a new genus to accommodate Hormiscium dermatitidis. Mycotaxon 5:353-367. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGinnis, M. R. 1978. Taxonomy of Exophiala jeanselmei (Langeron) McGinnis and Padhye. Mycopathologia 65:79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meletiadis, J., J. F. G. M. Meis, G. S de Hoog, and P. E. Verweij. 2000. In vitro susceptibilities of 11 clinical isolates of Exophiala species to six antifungal drugs. Mycoses 43:309-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaller, M. A., M. S. Bartlett, A. Espinal-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, F. C. Odds, J. H. Rex, M. G. Rinaldi, and T. J. Walsh. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi; approved standard M38-P. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 23.Rath, P.-M., K. D. Muller, H. Dermoumi, and R. Ansorg. 1997. A comparison of methods of phenotypic and genotypic fingerprinting of Exophiala dermatitidis isolated from sputum samples of patients with cystic fibrosis. Med. Mycol. 46:757-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossman, S. N., P. L. Cernoch, and J. R. Davis. 1996. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh, N., F. Y. Chang, T. Gayowski, and I. R. Marino. 1997. Infections due to dematiaceous fungi in organ transplant recipients: case report and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:369-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sudduth, E. J., A. J. Crumbley, and W. E. Farrar. 1992. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala species: clinical spectrum of disease in humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:639-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sughayer, M., P. C. DeGirolami, U. Khettry, D. Korzeniowski, A. Grummney, L. Pasarell, and M. R. McGinnis. 1991. Human infection caused by Exophiala pisciphila: case report and review. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:379-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutton, D. A., A. W. Fothergill, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1998. Guide to clinically significant fungi, p. 170-183. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 29.Tintelnot, K., G. S. de Hoog, E. Thomas, W.-I. Steudel, K. Huebner, and H. P. R. Seeliger. 1991. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis caused by an Exophiala species. Mycoses 34:239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai, C. Y., Y. C. Lu, L. T. Wang, T. L. Hsu, and J. L. Seng. 1966. Systemic chromoblastomycosis due to Hormodendrum dermatitidis (Kano) Conant. Report of the first case in Taiwan. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 46:103-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uijthof, J. M. J., G. S. de Hoog, A. W. de Cock, K. Takeo, and K. Nishimura. 1994. Pathogenicity of strains of the black yeast Exophiala (Wangiella) dermatitidis: an evaluation based on polymerase chain reaction. Mycoses 37:235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uijthof, J. M. J., and G. S. de Hoog. 1995. PCR-ribotyping of type isolates of currently accepted Exophiala and Phaeococcomyces species. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 68:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uijthof, J. M. J., A. van Belkum, G. S. de Hoog, and G. Haase. 1998. Exophiala dermatitidis and Sarcinomyces phaeomuriformis: ITS1-sequencing and nutritional physiology. Med. Mycol. 36:143-151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]