Abstract

Two hundred twenty isolates of Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139 collected from 1994 to 2002 in Hong Kong were analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Chromosomal DNAs from all V. cholerae isolates in agarose plugs were digested with the restriction enzyme NotI, resulting in 20 to 27 bands. Sixty distinctive PFGE patterns in the range of 10 to 300 kb were noted among 213 isolates typeable by PFGE. By comparing the common PFGE patterns obtained from four well-defined outbreaks of V. cholerae O1 and O139 with those obtained from other, epidemiologically unrelated isolates during the study period, indistinguishable and similar PFGE patterns were identified, indicating their close relatedness, in agreement with the results of epidemiological investigations. Heterogeneous PFGE patterns (with four to six banding differences), however, were identified among strains that were imported from other parts of Asia, including Indonesia, India, and Pakistan. Correlations with epidemiological information further support the usefulness of PFGE as an epidemiological tool in laboratory investigations of suspected outbreaks. Standardization of PFGE methodology will allow international comparison of fingerprint patterns and will form the basis of a laboratory network for tracking V. cholerae.

Serious pandemics of cholera have occurred throughout the known history of humankind. More recent data (12) from taxonomical evidence, epidemiological evidence, laboratory-based survival studies, and environmental isolations of Vibrio cholerae have provided evidence for the existence of an environmental reservoir which may be substantially influenced by climatic conditions (7). This has led to a better understanding of the epidemiological behavior of the organism. With the advent of molecular techniques, various DNA-based subtyping methods have been used to study interrelationships among V. cholerae strains at the genetic level. In particular, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) has been demonstrated in previous studies to be capable of analyzing relatedness (1, 15, 23).

Hong Kong is situated in the Pearl River delta and surrounded by brackish waters. The main water supply provides a safe water source for the whole local population, but cases of cholera still occur sporadically. Since the postwar years, cholera has been a notifiable disease in Hong Kong: the law requires that cholera cases be reported to the Department of Health. The Public Health Laboratory has examined specimens collected from patients as well as food samples from case investigations and has performed bacterial subtyping by conventional methods. In this study, the PFGE technique was used to examine and analyze the genetic interrelationships in our collection of V. cholerae strains, and results were correlated with epidemiological findings for defined outbreaks that have occurred where secondary spread of the organism is limited. Through this approach, we aimed to assess how PFGE can be useful in a longitudinal study of a collection of isolates in one defined locality. We report here the findings of this 9-year study of V. cholerae strains isolated during the period from 1994 to 2002 in Hong Kong.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

When the Department of Health received notifications of cases of V. cholerae infection, a team of health staff would initiate epidemiological investigation into each case. Information was collected by use of a standardized questionnaire. Isolation and treatment of cases, as well as disinfection of the environment, were immediately performed by health office staff. Data have been computerized into a database since 1989. These epidemiological data were retrieved from the database for analysis. Both local and imported cases were included in these investigations.

Bacterial strains.

All V. cholerae O1 and O139 strains isolated from patient specimens in clinical laboratories and from environmental samples in Hong Kong were sent to the Public Health Laboratory of the Department of Health for confirmation. The laboratory participated in the investigations of sporadic cholera cases as well as of outbreaks whenever they occurred in the territory. It has performed phenotypic characterizations, such as serotyping and biotyping, of V. cholerae isolates since 1969.

All bacterial identifications of V. cholerae strains were confirmed by conventional biochemical tests (4, 9) and the commercial API 20E and Vitek identification systems (bioMerieux, Lyon, France). Serotyping was determined by slide agglutination with polyvalent O1 and monospecific Inaba and Ogawa antisera (Murex, Dartford, United Kingdom) and was checked with an O139 antiserum (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan). Biotyping was performed by known standard methods (4). All strains were maintained at −80°C by using Protec beads (TSC Ltd., Heywood, Lancashire, United Kingdom).

PFGE.

PFGE was performed according to the PulseNet 1-day standardized PFGE protocol for subtyping Escherichia coli O157:H7 (6) with modifications. Briefly, an isolated colony from an individual V. cholerae strain was streaked onto Columbia agar with 5% horse blood and incubated at 37°C for 14 to 18 h. Agarose plugs were prepared by mixing equal volumes of bacterial suspensions with molten 1% SeaKem Gold (FMC Bioproducts)-1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (Boehringer Mannheim) agarose. Cells were lysed and washed before restriction digestion, which was carried out with 30 U of NotI at 37°C for 4 h and with 30 U of SfiI at 50°C for 4 h (both from Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The DNA size standard consisted of lambda ladder concatemers from 48.5 to 1,000 kbp (FMC Bioproducts). Restriction fragments were separated on a CHEF MAPPER (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). The run time was 18 h, with a voltage gradient of 6 V per cm and a linear ramp of 2.16 to 17.33 s. The gel was stained with 1 mg of ethidium bromide solution (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml and destained with reagent grade water. Images were captured with a Gel Doc 2000 system (Bio-Rad).

PFGE patterns were analyzed by Molecular Analyst Fingerprinting Plus software. Pattern profiles were compared by using the Dice coefficient and UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages) clustering with a 1.3% tolerance window. Indistinguishable patterns were confirmed visually. The percentage of band tolerance and the range of restriction fragments used for analysis were based on the results of different runs of single isolates of V. cholerae El Tor O1 Ogawa from our culture collection. PFGE pattern numbers were assigned to distinctive restriction fragment patterns based on the order in which the patterns were observed. Patterns numbers were assigned solely for discussion purposes and do not imply any relatedness between isolates.

RESULTS

During the 9-year period from 1994 to 2002, a total of 235 V. cholerae O1 and O139 isolates from human stool specimens and another 11 from environmental sources were confirmed by the Public Health Laboratory. Twenty-seven human isolates and 1 isolate from fish tank water were irrecoverable, so that 218 V. cholerae strains from our culture collection were available for study. In addition, two strains from India (V. cholerae El Tor O1 Ogawa strains KC and KS, kindly provided by G. B. Nair, National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases, Calcutta, India) were also included in this study. A total of 220 V. cholerae O1 and O139 strains were subsequently analyzed by PFGE.

Of the 218 V. cholerae isolates from our culture collection, 208 strains were isolated from human stool specimens and 10 strains were from environmental sources: 7 from fish tank water, 1 from seawater, 1 from raw turtle, and 1 from raw shrimp. There is no apparent epidemiological link between strains from individuals and strains from environmental sources, except for one isolate from fish tank water that was recovered during a cholera case investigation in 1994. The number of V. cholerae isolates was highest in the year 1998, followed by 2001 and 1994.

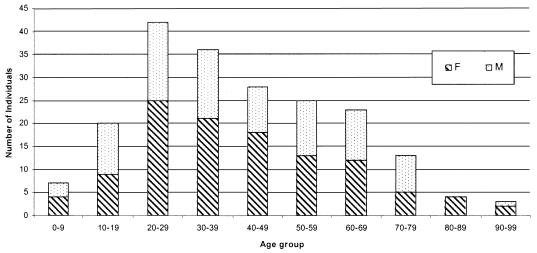

Information on the age and sex of individual patients was available for 201 isolates. The age range of patients was 7 months to 91 years (median, 38 years), and 65% of the individuals from whom V. cholerae O1 or O139 isolates were recovered were in the 20-to-39-year or 40-to-59-year age group (Fig. 1). The female-to-male ratio of affected patients was 1.28:1.

FIG. 1.

Age and sex distributions of individuals from whom V. cholerae was isolated in Hong Kong from 1994 to 2002.

Bacterial isolates.

From 1994 to 2002, no V. cholerae O1 Classical isolate was found. Within this 9-year period, 200 V. cholerae El Tor O1 and 18 V. cholerae O139 strains were analyzed (Table 1). Among the 200 V. cholerae El Tor O1 strains, 156 belonged to serotype Ogawa and 44 belonged to serotype Inaba. No serotype Inaba strain was isolated in 1995, 1996, 1997, or 2002. Interestingly, V. cholerae O139 strains were isolated from clinical or environmental specimens every 2 years starting from 1994.

TABLE 1.

Serotype distribution of 218 V. cholerae isolates obtained from 1994 to 2002 in Hong Kong

| Yr of isolation | No. of isolates from stool specimens of patients

|

No. of isolates from environmental sources

|

Total no. of isolates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | ||

| 1994 | 28 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 42 | ||

| 1995 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| 1996 | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| 1997 | 15 | 15 | |||||

| 1998 | 62 | 1 | 9 | 72 | |||

| 1999 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 15 | |||

| 2000 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 13 | ||

| 2001 | 14 | 26 | 6 | 46 | |||

| 2002 | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Total | 149 | 43 | 16 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 218 |

During the study period, 208 V. cholerae O1 and O139 isolates from humans were analyzed. Of the 208 isolates, 124 were recovered from patients who had no history of overseas travel (local cases), 80 were recovered from patients who had just returned from other countries (imported cases), and the remaining 4 were recovered from three asymptomatic carriers found during case investigations and from one patient whose source of contracting the pathogen was unknown (Table 2). Epidemiological data showed that the imported cholera cases were from different countries in this region: 19 from other provinces of mainland China, 1 from India, 3 from Indonesia, 1 from Nepal, 4 from Pakistan, 12 from the Philippines, 30 from Thailand, and 10 from other countries. Most (81%) of the V. cholerae O1 strains isolated in imported cases belonged to serotype Ogawa. Only 5 V. cholerae O1 serotype Inaba strains and 10 O139 strains have been isolated from patients with histories of overseas travel. Imported cholera cases were not uncommon in Hong Kong except in 1997. The lowest and highest percentages of imported cases relative to all cases were 12 and 60%, seen in 1994 and 1998, respectively. Apparently, an increasing percentage of cases was found to be imported from places outside Hong Kong.

TABLE 2.

Local and imported case distribution of 208 V. cholerae isolates obtained from 1994 to 2002 in Hong Kong

| Origin or definition of case | No. of strains with the indicated serotype recovered in:

|

Total no. of isolatesa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994

|

1995

|

1996

|

1997

|

1998

|

1999

|

2000

|

2001

|

2002 (Ogawa) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | Ogawa | Inaba | O139 | |||

| Local | 24 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 15 | 27 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 24 | 2 | 124 | |||||||||

| Mainland China | 1 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||

| India | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Indonesia | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nepal | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pakistan | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philippines | 11 | 1 | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thailand | 29 | 1 | 30 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other countries | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carrier | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 28 | 11 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 62 | 1 | 9 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 14 | 26 | 0 | 4 | |

The total number of isolates recovered in each study year was as follows: 41 in 1994, 5 in 1995, 5 in 1996, 15 in 1997, 72 in 1998, 14 in 1999, 12 in 2000, 40 in 2001, and 4 in 2002.

Epidemiological information from four well-defined cholera outbreaks which occurred in three years—one in 1994 (13), two in 1998, and one in 2001—was available. In three of these outbreaks, only V. cholerae O1 El Tor strains were isolated, while V. cholerae O139 strains were isolated in the remaining outbreak, in 1998 (14). An outbreak of 12 cholera cases occurred in Hong Kong during a 3-week period in June and July 1994 (13). Epidemiological investigations showed linkage in all cases with consumption of seafood, including shellfish, mantis shrimp, and crabs. Microbiological findings demonstrated that contaminated seawater in fish tanks used for keeping the seafood alive is the most likely vehicle of transmission. In March 1998, a total of 29 cholera cases, caused by V. cholerae O1 El Tor Ogawa, were identified among four tour groups returning from Thailand that had similar itineraries organized by the same travel agency (10). In early September 2001, 11 cholera cases were confirmed microbiologically in a group of individuals who had joined a tour group to the Philippines with 30 collateral travelers. They had common meals, including various kinds of seafood, throughout the trip. Seven V. cholerae O139 isolates were isolated from another group of individuals who had traveled to Zhuhai in Guangdong province, mainland China, in May 1998 (14). A variety of seafood consumed by the tour members was suspected as the source of contamination.

During the cholera outbreak investigations, there had been instances in which different V. cholerae El Tor O1 serotypes (both the Ogawa and Inaba serotypes) were isolated from the stool specimens of a single individual. In 1994, V. cholerae El Tor O1 Inaba was isolated from the stool specimen of an individual, followed 1 day later by an Ogawa isolate recovered from another stool specimen of the same patient. Among the tour groups that traveled to Thailand in 1998 and to the Philippines in 2001, both Ogawa and Inaba isolates have been found in the stool specimens of single individuals who had just returned from these trips.

PFGE.

The choice of restriction endonuclease in PFGE testing was one of the important factors affecting our results. In previous PFGE studies of V. cholerae, NotI (5′-GCGGCCGC-3′) was the most common restriction endonuclease used, followed by SfiI (5′-GGCCNNN-3′). Both enzymes were used to perform PFGE analysis at the beginning of this study. However, our previous findings (data not shown) showed that SfiI digestion almost always gave indistinguishable PFGE patterns for our V. cholerae strains, so that they had to be confirmed by NotI digestion, which produced patterns with higher discrimination. Consequently, NotI was employed as the enzyme of choice for this study.

To assess the genetic interrelationship of V. cholerae strains, 220 V. cholerae O1 and O139 strains were subtyped by PFGE using the restriction endonuclease NotI. Seven V. cholerae El Tor O1 Ogawa strains isolated in 2001 could not be typed by PFGE and consistently appeared as a smear on the gel, even when thiourea was added to the running buffer (8, 19). Among the seven strains that were not typeable by PFGE, two were isolated from stool specimens of individuals (one from a carrier and one from a patient) while five were isolated from environmental samples (four from fish tank water and one from raw shrimp). There is no apparent epidemiological link between the strains isolated from individuals and those obtained from environmental sources. PFGE patterns remained stable and reproducible when the analyses of V. cholerae strains were repeated within the study period.

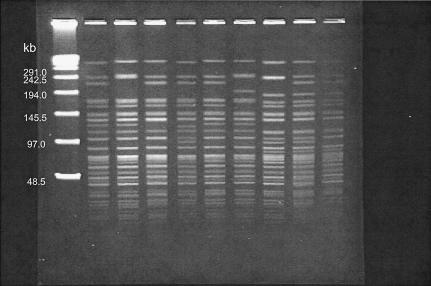

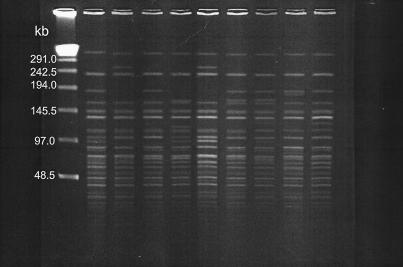

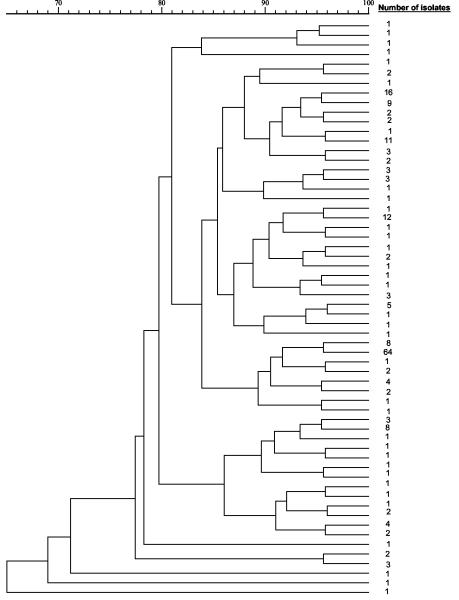

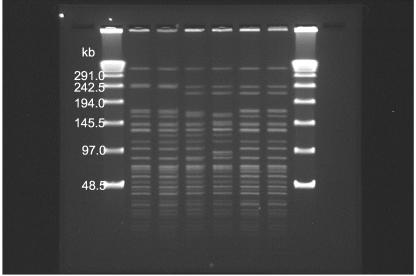

As shown in Fig. 4 and 5, the largest band present is above 300 kb. All but two of the V. cholerae El Tor O1 Ogawa strains consistently gave this band. However, inclusion of this band made the computer program misinterpret even identical fingerprints of the same isolates from different runs as different fingerprints. One possible explanation is that this band (300 kb) is out of range of lambda ladder size markers, thus leading to extrapolation of molecular sizes, which resulted in unreliable measurements. Consequently, this band was excluded from analysis by use of the computer program. The range of restriction fragments used for analysis was therefore 10 to 300 kb. A total of 60 different PFGE patterns were identified among 213 isolates typeable by PFGE (Fig. 2). The number of restriction fragments generated by NotI within the analytical zone ranged from 20 to 27. All, except three, consistently gave 12 identical banding patterns in the range of 10 to 75 kb. The most apparent differences among distinguishable strains were the larger restriction fragments ranging from 80 to 250 kb.

FIG. 4.

PFGE fragment patterns of NotI-digested total cellular DNAs from representative V. cholerae O1 strains isolated in Hong Kong. Lanes, from left to right, are as follows: multimers of phage lambda DNA (48.5 kb) as molecular size markers, VCEIN0801 (pattern 1), VETOG12A94 (pattern 28), VCEIN0199 (pattern 13), VCEIN0301 (pattern 6), VCEOG0701 (pattern 7; the Philippines), VETOG0195 (pattern 37; Indonesia), VIB7-0003 (pattern 46; Pakistan), VCEOG0396 (pattern 56; Nepal), and VCEOG0101 (pattern 57; India).

FIG. 5.

PFGE fragment patterns of NotI-digested total cellular DNAs from representative V. cholerae O139 strains isolated in Hong Kong. Lanes, from left to right, are as follows: multimers of phage lambda DNA (48.5 kb) as molecular size markers, VCO1390294 (pattern 51), VCO1390198 (pattern 42), VCO1390298 (pattern 48), VCO1390398 (pattern 40), VCO1390898 (pattern 43), VCO1390998 (pattern 52), VCO1390200 (pattern 47), VCO1390300 (pattern 50), and VCO1390500 (pattern 49).

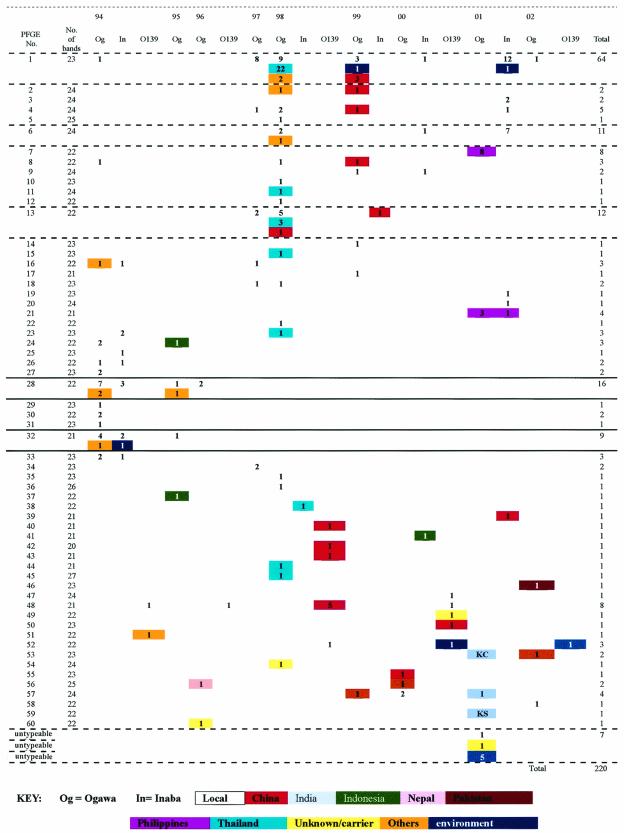

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of 60 PFGE subtype patterns of 213 V. cholerae strains isolated in Hong Kong between 1994 and 2002.

Among the 60 distinctive PFGE patterns, pattern 1, containing 23 bands, was the predominant pattern, found in 50 V. cholerae O1 Ogawa and 14 V. cholerae O1 Inaba strains (Fig. 3). The next three dominant patterns were patterns 28, 13, and 6, consisting of 22, 22, and 24 bands, respectively. Strains isolated from 1994 to 1996 appeared to cluster mainly between patterns 16 and 33, while those isolated from 1997 to 2002 mainly clustered between patterns 1 and 13. The uncommon occurrence of 1994-to-1996 PFGE patterns among isolates found recently may be due to natural shifts in Vibrio populations or to enforcement of regulations prohibiting the use of contaminated fish tank water after the 1994 outbreak. Moreover, patterns 40 to 60 were mainly found in strains from carriers (all O1 strains from carriers and all O139 strains had one of these PFGE patterns) and those recovered from imported cases. The wide differences in PFGE pattern between O1 and O139 strains appear to suggest that the evolution of these clones followed quite different pathways. Nine distinctive PFGE patterns were found among the 18 V. cholerae O139 strains, and this diversity was not observed among isolates of V. cholerae O1. Further follow-up and PFGE examination of future strains will help to elucidate their interrelationships.

FIG. 3.

Distribution of 60 PFGE patterns of V. cholerae in Hong Kong (1994 to 2002).

In order to better understand how epidemiologically defined outbreak isolates were related to each other at the genetic level, PFGE patterns of isolates from each outbreak were studied and compared. For outbreaks with an identified source of contamination such as that in 1994, the PFGE pattern of the isolate from the source (fish tank water) was designated as the reference outbreak pattern for comparison with other isolates obtained from that outbreak. Because the source of contamination could not be confirmed microbiologically for the other three, imported outbreaks, the predominant PFGE pattern in each outbreak was selected and designated as the common pattern for further comparison with the epidemiologically related strains. The numbers of banding differences among these outbreak strains were then enumerated (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Numbers of band differences between PFGE patterns of V. cholerae strains and that of a designated type strain obtained with the restriction enzyme NotI

| Mo and yr of outbreak | Description of isolates (no. tested) | Designated outbreak pattern no. or common pattern no. | No. (%) of isolates with the following no. of differences from the reference or common pattern:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| June 1994 | Fish tank water-associated outbreak (7) | 32 | 2 (28.6) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (28.6) | 0 | 0 |

| March 1998 | Tour group to Thailand (29) | 1 | 22 (75.9) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 2 (6.9) |

| May 1998 | Tour group to Zhuhai, China (7) | 48 | 5 (71.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (28.6) |

| September 2001 | Tour group to the Philippines (11) | 7 | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

From 12 cholera cases caused by V. cholerae O1 El Tor Inaba found during the local cholera outbreak in 1994, 7 V. cholerae O1 El Tor Inaba strains (6 from patients and 1 from a fish tank water sample) were analyzed by PFGE. The PFGE patterns of an isolate recovered from restaurant fish tank water and an isolate from a patient who had eaten shrimp in that restaurant were indistinguishable (pattern 32). A one-band difference at 122 kb was observed when the patterns of isolates from three other patients were compared with pattern 32. The PFGE patterns of the two remaining patient isolates were closely related to, but distinct from, the outbreak pattern and each other. Specifically, the PFGE pattern of one strain (VETIN0294) differed from pattern 32 by two bands: it had two additional bands at 124 and 94 kb. The other strain (VETIN2394) had two extra bands, at 122 and 118 kb, relative to pattern 32.

Of 29 V. cholerae O1 El Tor Ogawa strains isolated during the imported outbreak of March 1998 that were subtyped by PFGE, 22 appeared to have the same banding pattern, pattern 1 (Fig. 4). Patterns of the remaining seven patient isolates were distinct from pattern 1 and from each other. One missing band at 122 kb was noted for PFGE pattern 13 (three isolates) relative to pattern 1. Two band differences were observed between pattern 15 and pattern 1: pattern 15 had one additional band at 136 kb and one missing band at 122 kb. Pattern 23 differed from pattern 1 by two bands: one missing band at 212 kb and one additional band at 94 kb. Patterns 44 and 45 were each distinguishable from pattern 1 by four-band differences.

In addition, different but closely related PFGE patterns were observed among isolates from a group of 11 patients who visited the Philippines in September 2001. For 11 V. cholerae O1 El Tor Ogawa isolates subtyped by PFGE, two PFGE patterns (pattern 7 and pattern 21) were seen. An additional band at 121 kb was present in pattern 7 relative to pattern 21.

Three different PFGE patterns were noted among the seven V. cholerae O139 strains isolated from individuals who traveled in the same tour group to Zhuhai in Guangdong province, mainland China, in May 1998. Five of the seven patient isolates displayed indistinguishable PFGE patterns (pattern 48) (Fig. 5). The PFGE patterns of the remaining two patient isolates were different from pattern 48 and from each other. Four band differences were detected between the PFGE pattern of strain VCO1390398 and PFGE pattern 48, viz., two missing bands at 180 and 81 kb and two additional bands at 122 and 94 kb (Fig. 5). The PFGE pattern of strain VCO1390898 differed from pattern 48 by four bands: two additional bands at 259 and 96 kb and two missing bands at 180 and 81 kb (Fig. 5).

Furthermore, we also compared the PFGE patterns of V. cholerae El Tor O1 Ogawa and Inaba isolates from the stool specimens of single individuals during the cholera outbreaks. In the 1994 local outbreak, a one-band difference in the restriction fragment pattern was noted between Inaba and Ogawa isolates from two stool specimens of a single individual: an extra band of 119 kb was present in the Ogawa isolate relative to the Inaba isolate (Fig. 6). Moreover, a three-band difference in the PFGE pattern was also found between Ogawa and Inaba isolates from the same stool specimen of an individual in the Thai tour group in 1998, viz., two missing bands at 159 and 162 kb and one additional band at 89 kb. On the other hand, indistinguishable restriction fragment patterns were observed for Ogawa and Inaba isolates from the stool of a single individual in the tour group visiting the Philippines in 2001.

FIG. 6.

PFGE fragment patterns of NotI-digested total cellular DNAs from representative V. cholerae O1 strains isolated in Hong Kong. Leftmost and rightmost lanes, multimers of phage lambda DNA (48.5 kb) as molecular size markers. Inner lanes, from left to right, are as follows: VETIN1294 and VETOG0294 are the first pair of Inaba and Ogawa isolates from the 1994 outbreak, VCEOG4598 and VCEIN0198 are the second pair of Ogawa and Inaba isolates from the 1998 outbreak, and VCEOG0801 and VCEIN2301 are the third pair of Ogawa and Inaba isolates from the 2001 outbreak.

Indistinguishable PFGE patterns were also sometimes observed when we compared our local sporadic Hong Kong V. cholerae O1 strains with isolates from different Asian countries (Fig. 3). Most notably, indistinguishable PFGE patterns were found for Hong Kong O1 strains and some O1 strains from Thailand as well as those from other parts of mainland China (pattern 1). This constitutes evidence that sporadic cases caused by closely related strains of V. cholerae occurred regularly, and it would be difficult to interpret PFGE fingerprints based on banding patterns alone. Therefore, information on strain relatedness based on PFGE banding differences should be interpreted in light of epidemiological findings.

One PFGE pattern obtained from V. cholerae O139 strains from China was shared with our local O139 strains: pattern 48. In addition, one- to two-band differences in the PFGE pattern were noted between local strains and those from the Philippines in 2001. On the other hand, much heterogeneity was observed (four to six band differences) when PFGE patterns identified among our local strains (pattern 1) were compared with those found in imported strains from India, Indonesia, and Pakistan which were isolated within the same year.

Three V. cholerae O1 El Tor Ogawa strains from apparently local cases (two from 2000, with pattern 57, and one from 2002, with pattern 58) displayed PFGE patterns very different from those of other local strains (Fig. 3). Further epidemiological information revealed that the two strains isolated in 2000 were from children who were epidemiologically linked to another patient who had just returned from Pakistan and whose strain showed PFGE pattern 56. The remaining strain was isolated from a senior citizen who also suffered from other, chronic diseases.

DISCUSSION

PFGE has previously been proven to be a worthwhile method for investigating the clonal relationship among enteric pathogens, such as E. coli O157:H7, Campylobacter jejuni, Listeria monocytogenes, and Clostridium perfringens (2, 3, 17, 18). The power of this typing technique for V. cholerae has also been demonstrated in previous studies (1, 5, 20, 22). In this study, we attempted to perform molecular subtyping of V. cholerae O1 and O139 by PFGE in Hong Kong and to correlate the results with epidemiological events within a 9-year period.

With the epidemiological data collected, we were able to analyze the PFGE patterns of isolates in an outbreak situation and to correlate their relatedness in terms of the number of band differences in PFGE patterns. These results are in close agreement with those previously proposed for PFGE typing of bacterial strains in general (21). Because the existing infrastructure, viz., provision of a safe main water supply for the whole population, in Hong Kong does not allow secondary spread of cholera, our collection of V. cholerae isolates in this study accurately reflects the true occurrence of pathogenic V. cholerae organisms in the brackish-water environmental reservoir that can directly contaminate food sources. This epidemiological situation is different from that seen in areas of hyperendemicity, where V. cholerae may spread easily beyond its natural reservoir. The results of this study further support the utility of PFGE in evaluating V. cholerae strain interrelationships at the genomic DNA level, particularly in epidemiological situations where good infrastructure limits secondary spread of the organism beyond its primary infecting source, therefore possibly limiting chances for further changes in PFGE patterns.

One of the isolates from the 1994 cholera outbreak was obtained from a seawater sample in a fish tank used for keeping seafood alive. Indistinguishable PFGE patterns shared by this strain and an isolate from a patient strongly showed that the fish tank water was the source of transmission. Although among 12 cholera patients only 6 V. cholerae O1 El Tor Inaba strains were available for PFGE analysis, these 6 patients' isolates represented different phases of isolation during the 3-week period of the outbreak. What were seen as one- to two-band differences between the PFGE patterns of V. cholerae isolates from the five other patients and the outbreak pattern suggested that genetically closely related clones were responsible for this outbreak (Table 3). The one- to two-band differences in PFGE patterns within the five strains related to the outbreak suggested a single genetic event such as a point mutation, an insertion, or a deletion (21). Similarly, a common PFGE pattern was also displayed by the majority of V. cholerae O1 El Tor Ogawa isolates in an imported cholera outbreak in 1998. Five patient isolates had PFGE patterns distinct from, but closely related to, the predominant pattern (differing in one to two bands). The heterogeneous PFGE patterns (differences of as many as four bands) of the remaining two human isolates relative to the predominant PFGE pattern in this outbreak can be explained by two independent genetic events such as simple insertions or deletions with gains or losses in restriction sites. This suggests that the two patients may have been subjected to different sources of contamination, but it was not possible to confirm this conjecture epidemiologically. More detailed information on the tour group to which these patients belonged and a comparison of tour itineraries may help to explain this dissimilarity.

The recent imported cholera outbreak in 2001 further demonstrated the usefulness of PFGE analysis in supporting epidemiological findings in our study of tour groups. Two similar restriction fragment patterns (with a one-band difference) were noted for the 11 individuals who traveled together to the Philippines. For the outbreak caused by V. cholerae O139, indistinguishable PFGE patterns were observed for five V. cholerae O139 isolates from individuals who traveled together to Zhuhai, China. Very distinct patterns, however, were found for two isolates from patients in the same tour group. No further epidemiological information was available to explain the very distinct PFGE patterns that were identified for these two individuals. A previous study showed that cholera outbreaks can be caused by a single clone or very closely related clones with very similar PFGE patterns (15). It has been postulated that our finding might be caused by different strains or by a single strain that has undergone genetic changes at sites specific for the restriction enzyme.

Nearly simultaneous appearances of isolates of both O1 serotypes, Ogawa and Inaba, from the stool of a single individual were observed during the study period. Since only three such events occurred, it seemed that these were more apparent during cholera outbreaks. However, this has to be confirmed by additional studies. It is known that V. cholerae O1 strains can undergo serotype conversion between Ogawa and Inaba (16). A three-band difference in PFGE patterns between the O1 Ogawa and Inaba isolates from the same individual in the 1998 imported outbreak may suggest coinfection with two V. cholerae clones belonging to different serotypes. On the other hand, the indistinguishable PFGE patterns of the O1 Ogawa and Inaba strains isolated from the same individual after travel to the Philippines suggested that these strains were from the same clone or very closely related clones. In addition, O1 Ogawa and Inaba isolates recovered from the same individual in 1994 differed by only one band, which indicated that they were genetically very closely related. DNA sequencing of the wbeT region will help to elucidate whether the isolation of both serotypes from the stool of a single individual is due to true serotype switching between the Ogawa and Inaba serotypes (24). Further subtyping work will help to address whether indigenous V. cholerae O1 strains can acquire toxin genes or other properties that render them pathogenic or bear epidemic potential.

The sharing of a prominent PFGE banding pattern (pattern 1) by V. cholerae O1 El Tor Ogawa strains isolated in 1998 and in 1999 and V. cholerae O1 El Tor Inaba strains isolated in 2001, but not by Inaba strains isolated in 1994, implies that the Inaba strains that emerged recently are similar to the prevailing O1 Ogawa strains (11). The fact that this local clone possesses a PFGE pattern indistinguishable from those from Thailand and mainland China may suggest that this is a prevailing strain in the South China Sea region (1). Nonetheless, in comparison with our locally predominant strains, heterogeneous PFGE patterns from other Asian countries, such as India, Indonesia, and Pakistan, are likely to be due to epidemiological differences as well as to the selective pressures that exist in different localities. Future collaboration with more countries, particularly those in Asia, will definitely contribute to our understanding in this important area of cholera epidemiology.

Timely laboratory typing results are of paramount importance in helping outbreak investigators to trace the source of contamination so that appropriate preventive measures may be taken to stop further spread of illnesses. Consequently, rapid PFGE protocols for various enteric pathogens have been evaluated and standardized by the PulseNet of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (6). To demonstrate the possibility of employing a rapid PFGE protocol for V. cholerae, PFGE was performed by the PulseNet method with modifications in this study and showed promising results. The rapid protocol allows restricted DNA plugs to be run within 1 day. With the running conditions provided by the PulseNet (B. Swaminathan, personal communication), restricted fragments were spaced suitably to show the distinguishable differences in patterns among strains. Similar, if not unified, PFGE procedures for important enteric pathogens such as isolates of E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., and V. cholerae will facilitate the work of the public health laboratories that perform these tests by diminishing the costs and problems associated with using different reagent preparations, as well as those associated with carrying out different PFGE procedures that may be dedicated for use with an individual pathogen only. In order to promote effective bacterial and epidemiological tracking and control of the disease, internationally standardized typing procedures and an international PFGE fingerprint database should be set up for public health laboratories.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the scientific and technical staff working in the Public Health Laboratories, Department of Health, for excellent support of this study, and the Director of Health, Margaret Chan, for permission to publish this report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakawa, E., T. Murase, S. Matsushita, T. Shimada, S. Yamai, T. Ito, and H. Watanabe. 2000. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis-based molecular comparison of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolates from domestic and imported cases of cholera in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:424-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autio, T., S. Hielm, M. Miettinen, A.-M. Sjöberg, K. Aarnisalo, J. Björkroth, T. Mattila-Sandholm, and H. Korkeala. 1999. Sources of Listeria monocytogenes contamination in a cold-smoked rainbow trout processing plant detected by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:150-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett, T. J., H. Lior, J. H. Green, R. Khakhria, J. G. Wells, B. P. Bell, K. D. Greene, J. Lewis, and P. M. Griffin. 1994. Laboratory investigation of a multistate food-borne outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and phage typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:3013-3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, A. K., C. A. Bopp, and J. G. Wells. 1994. Isolation and identification of Vibrio cholerae O1 from fecal specimens, p. 3-26. In I. K. Wachsmuth, P. A. Blake, and Ø. Olsvik (ed.), Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 5.Cameron, D. N., F. M. Khambaty, I. K. Wachsmuth, R. V. Tauxe, and T. J. Barrett. 1994. Molecular characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1685-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000. Standardized molecular subtyping of foodborne bacterial pathogens by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: training manual. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

- 7.Colwell, R. R., and A. Huq. 1994. Vibrios in the environment: viable but nonculturable Vibrio cholerae, p. 117-133. In I. K. Wachsmuth, P. A. Blake, and Ø. Olsvik (ed.), Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Corkill, J. E., R. Graham, C. A. Hart, and S. Stubbs. 2000. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of degradation-sensitive DNAs from Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 1 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2791-2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowan, S. T., and K. J. Steel. 1974. Manual for the identification of medical bacteria, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 10.Department of Health, Hong Kong Government. 1998. Imported cholera cases among tours returning from Thailand. Public Health Epidemiol. Bull. 7: 2-5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg, P., R. K. Nandy, P. Chaudhury, N. R. Chowdhury, K. De, T. Ramamurthy, S. Yamasaki, S. K. Bhattacharya, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2000. Emergence of Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor serotype Inaba from the prevailing O1 Ogawa serotype strains in India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4249-4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Islam, M. S., B. S. Drasar, and R. B. Sack. 1996. Ecology of Vibrio cholerae: role of aquatic fauna and flora, p. 187-227. In B. S. Drasar and B. D. Forrest (ed.), Cholera and the ecology of Vibrio cholerae. Chapman and Hall, London, United Kingdom.

- 13.Kam, K. M., T. H. Leung, P. Y. Ho, K. Y. Ho, and T. A. Saw. 1995. Outbreak of Vibrio cholerae O1 in Hong Kong related to contaminated fish tank water. Public Health 109:389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kam, K. M., K. Y. Luey, T. L. Cheung, K. Y. Ho, K. H. Mak, and P. T. A. Saw. 1999. Ofloxacin-resistant Vibrio cholerae O139 in Hong Kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:595-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahalingam, S., Y. M. Cheong, S. Kan, R. M. Yassin, J. Vadivelu, and T. Pang. 1994. Molecular epidemiologic analysis of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2975-2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manning, P. A., U. H. Stroeher, and R. Morona. 1994. Molecular basis for O-antigen biosynthesis in Vibrio cholerae O1: Ogawa-Inaba switching, p. 77-94. In I. K. Wachsmuth, P. A. Blake, and Ø. Olsvik (ed.), Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 17.Maslanka, S. E., J. G. Kerr, G. Williams, J. M. Barbaree, L. A. Carson, J. M. Miller, and B. Swaminathan. 1999. Molecular subtyping of Clostridium perfringens by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to facilitate food-borne-disease outbreak investigations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2209-2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribot, E. M., C. Fitzgerald, K. Kubota, B. Swaminathan, and T. J. Barrett. 2001. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for subtyping of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1889-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Römling, U., and B. Tümmler. 2000. Achieving 100% typeability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:464-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha, S., R. Chakraborty, K. De, A. Khan, S. Datta, T. Ramamurthy, S. K. Bhattacharya, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2002. Escalating association of Vibrio cholerae O139 with cholera outbreaks in India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2635-2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vadivelu, J., L. Iyer, B. M. Kshatriya, and S. D. Puthucheary. 2000. Molecular evidence of clonality among Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor during an outbreak in Malaysia. Epidemiol. Infect. 124:25-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wachsmuth, K., Ø. Olsvik, G. M. Evins, and T. Popovic. 1994. Molecular epidemiology of cholera, p. 357-370. In I. K. Wachsmuth, P. A. Blake, and Ø. Olsvik (ed.), Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 24.Yamasaki, S., S. Garg, G. B. Nair, and Y. Takeda. 1999. Distribution of Vibrio cholerae O1 antigen biosynthesis genes among O139 and other non-O1 serogroups of Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]