Abstract

A real-time PCR for the ABI Prism 7000 system targeting the 23S-5S spacer of Legionella spp. was developed. Simultaneous detection and differentiation of Legionella spp. and Legionella pneumophila within 90 min and without post-PCR melting-curve analysis was achieved using two TaqMan probes. In sputum samples from 23 controls and 17 patients with legionellosis, defined by positive culture, urinary antigen testing, or seroconversion, 94% sensitivity and 100% specificity were observed.

Legionellae, the causative agents of legionellosis, are fastidious, slow-growing bacteria that are ubiquitous in freshwater systems. Although 48 different Legionella species have been described, 90% of all recorded cases of legionellosis are due to Legionella pneumophila (6). The prognosis for legionellosis depends partially on rapid and accurate diagnosis (8). However, conventional diagnostic techniques—like culture on selective media; direct and indirect immunoassays of pulmonary secretions and serum, respectively; and urinary antigen tests—lack either speed or sensitivity (6). Therefore, direct detection of Legionella DNA in clinical samples is a challenging alternative, and much effort has been put into developing PCR and, more recently, real-time PCR assays. These molecular techniques have targeted the mip gene, e.g. (1, 7), 5S ribosomal DNA (7), 16S ribosomal DNA (11, 12, 14, 16), and the 23S-5S spacer (15). While the mip gene was initially used as an L. pneumophila-specific marker (2), other legionellae were also found to harbor this gene (3, 13). The 5S and 16S rRNA genes are such well-conserved regions that it is difficult to differentially detect L. pneumophila and other Legionella species on a real-time basis without subsequent tests (7, 14) or that there is a risk of amplification of the DNAs of other than Legionella species (4). All the real-time PCR protocols described above use the LightCycler system.

Here, we describe a dual-color, real-time PCR assay for the ABI Prism 7000 system to detect and quantitate legionellae. By using two different TaqMan probes on one amplicon in the more variable 23S-5S spacer region previously described (15), we were able to differentiate in real time between L. pneumophila and other Legionella species.

All available 23S-5S spacer sequences of Legionella were manually aligned with the DCSE software (5), and primers that would specifically amplify the smallest possible fragment of all Legionella species were chosen. The resulting primer set, LegF (5′-CTA ATT GGC TGA TTG TCT TGA C-3′) and LegR (5′-GGC GAT GAC CTA CTT TCG-3′) (15), amplified a 259-bp DNA fragment which was detected in real time by a Legionella genus probe, which was conjugated to a minor groove binder (5′-VIC-CGA ACT CAG AAG TGA AAC-3′) to raise the annealing temperature. To differentiate between L. pneumophila and other legionellae, a second, L. pneumophila-specific probe (5′-FAM-ATC GTG TAA ACT CTG ACT CTT TAC CAA ACC TGT GG-3′) was chosen on the same amplicon.

DNAs were isolated from 40 strains of Legionella, including reference strains and clinical isolates from all 14 serogroups of L. pneumophila and 13 reference strains of other legionellae, by incubation at 95°C for 5 min in 100 μl of DNase-free water (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). A set of 52 DNA samples from reference strains and clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, Aeromonas hydrophila, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Bordetella parapertussis, Bordetella pertussis, Candida albicans, Eikenella corrodens, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Lactobacillus spp., Moraxella catarrhalis, Morganella morganii, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Proteus mirabilis, Proteus vulgaris, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Streptococcus salivarius served as negative controls.

Real-time PCR was performed in triplicate on an ABI Prism 7000 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) in mixtures of 12.5 μl of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix containing AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase, AmpErase uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG), deoxynucleoside triphosphates with dUTP, a passive reference dye, optimized buffer components (Applied Biosystems), 200 nM (each) primer, 200 nM (each) probe, 400 μg of bovine serum albumin (New England BioLabs)/ml, and 2.5 μl of template DNA in a total volume of 25 μl. After activation of AmpErase UNG (2 min; 50°C) and Taq polymerase (10 min; 95°C), 45 cycles of denaturation (15 s; 95°C) and elongation (1 min; 60°C) were passed.

With all L. pneumophila strains, both the genus and L. pneumophila probe detected the DNA fragment. Non-pneumophila strains were detected only with the genus probe. All experiments with negative controls showed no digestion of either probe (data not shown).

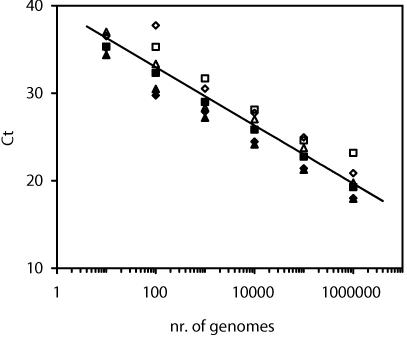

For quantitative analysis, suspensions of L. pneumophila serogroups 1, 4, and 10 (ATTC 33152, 33156, and 43283, respectively), L. bozemannii serogroup 1, L. israeliensis, and L. longbeachae serogroup 1 (ATCC 33217, 43119, and 33462, respectively) in DNase-free water (Sigma-Aldrich) were counted by DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining (10). DNA was then extracted from a known number of bacteria, and threshold cycles were determined in serial 10-fold dilutions ranging from 106 to 10 genomes per reaction well (Fig. 1). The PCR efficacies calculated from the threshold cycle standard curves were >95% for all six strains. In limiting-dilution assays, L. pneumophila was detected in all wells containing 10 genomes and in 17% of the wells theoretically containing 1 genome. This implies a detection limit of one copy per well.

FIG. 1.

Threshold cycles (Ct) and means for serial 10-fold dilutions of different Legionella strains detected with the genus probe. The PCR efficacy was calculated from the slopes of individual strains. ♦, L. pneumophila serogroup 1; ▪, L. pneumophila serogroup 4; ▴, L. pneumophila serogroup 10; ⋄, L. bozemannii serogroup 1; □, L. israeliensis; ▵, L. longbeachae serogroup 1.

DNA was isolated from respiratory samples from 17 patients with legionellosis and 23 controls. Cases of legionellosis were defined by positive culture, urinary antigen (9), or seroconversion in paired serum samples measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Virion-Serion, Würzburg, Germany). Control patients had pneumonia caused by agents other than Legionella, and mainly S. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and H. parainfluenzae were cultured. The samples were collected in 2001 and 2002 and retrospectively evaluated. DNA isolations were done with the QIAamp tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and isolation controls were processed using DNase-free water (Sigma-Aldrich). Although in 2002, up to 10 to 70% contamination of QIAamp columns with Legionella spp. was reported (A. van der Zee, M. Peeters, C. de Jong, H. Verbakel, J. W. Crielaard, E. C. Claas, and K. E. Templeton, Letter, J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1126, 2002), we found no contamination with Legionella spp. in these 40 samples. PCR results were positive for both genus and L. pneumophila probes in 16 patients and no controls, demonstrating 100% assay specificity and 94% sensitivity in these specimens. In all culture-positive specimens, PCR detected L. pneumophila. Obviously, prospective testing in a larger population is warranted for full clinical evaluation.

Our results show that the described assay is able to correctly detect L. pneumophila and to distinguish it from other legionellae in real time. In comparison to previously described real-time PCR assays (7, 12, 14), the more diverse 23S-5S target region allows these results without post-PCR sequencing or melting-curve analysis. In a clinical context, this implies 40 min of personnel hands-on time, including DNA isolation, followed by a maximum of 90 min of stand-alone assay time before the results are known. This rapid diagnostic testing and differentiation of clinical specimens provides a valuable tool in the evaluation of suspected legionellosis with the ABI Prism 7000.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballard, A. L., N. K. Fry, L. Chan, S. B. Surman, J. V. Lee, T. G. Harrison, and K. J. Towner. 2000. Detection of Legionella pneumophila using a real-time PCR hybridization assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4215-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cianciotto, N. P., B. I. Eisenstein, C. H. Mody, G. B. Toews, and N. C. Engleberg. 1989. A Legionella pneumophila gene encoding a species-specific surface protein potentiates initiation of intracellular infection. Infect. Immun. 57:1255-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cianciotto, N. P., W. O'Connell, G. A. Dasch, and L. P. Mallavia. 1995. Detection of mip-like sequences and Mip-related proteins within the family Rickettsiaceae. Curr. Microbiol. 30:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cloud, J. L., K. C. Carroll, P. Pixton, M. Erali, and D. R. Hillyard. 2000. Detection of Legionella species in respiratory specimens using PCR with sequencing confirmation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1709-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Rijk, P., and R. De Wachter. 1993. DCSE, an interactive tool for sequence alignment and secondary structure research. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 9:735-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields, B. S., R. F. Benson, and R. E. Besser. 2002. Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:506-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayden, R. T., J. R. Uhl, X. Qian, M. K. Hopkins, M. C. Aubry, A. H. Limper, R. V. Lloyd, and F. R. Cockerill. 2001. Direct detection of Legionella species from bronchoalveolar lavage and open lung biopsy specimens: comparison of LightCycler PCR, in situ hybridization, direct fluorescence antigen detection, and culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2618-2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heath, C. H., D. I. Grove, and D. F. Looke. 1996. Delay in appropriate therapy of Legionella pneumonia associated with increased mortality. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 15:286-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helbig, J. H., S. A. Uldum, P. C. Luck, and T. G. Harrison. 2001. Detection of Legionella pneumophila antigen in urine samples by the BinaxNOW immunochromatographic assay and comparison with both Binax Legionella Urinary Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) and Biotest Legionella Urine Antigen EIA. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:509-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porter, K. G., and Y. S. Feig. 1980. The use of DAPI for identifying and counting aquatic microflora. Limnol. Oceanogr. 25:943-948. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raggam, R. B., E. Leitner, G. Muhlbauer, J. Berg, M. Stocher, A. J. Grisold, E. Marth, and H. H. Kessler. 2002. Qualitative detection of Legionella species in bronchoalveolar lavages and induced sputa by automated DNA extraction and real-time polymerase chain reaction. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 191:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rantakokko-Jalava, K., and J. Jalava. 2001. Development of conventional and real-time PCR assays for detection of Legionella DNA in respiratory specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2904-2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratcliff, R. M., S. C. Donnellan, J. A. Lanser, P. A. Manning, and M. W. Heuzenroeder. 1997. Interspecies sequence differences in the Mip protein from the genus Legionella: implications for function and evolutionary relatedness. Mol. Microbiol. 25:1149-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reischl, U., H. J. Linde, N. Lehn, O. Landt, K. Barratt, and N. Wellinghausen. 2002. Direct detection and differentiation of Legionella spp. and Legionella pneumophila in clinical specimens by dual-color real-time PCR and melting curve analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3814-3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson, P. N., B. Heidrich, F. Tiecke, F. J. Fehrenbach, and A. Rolfs. 1996. Species-specific detection of Legionella using polymerase chain reaction and reverse dot-blotting. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 140:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wellinghausen, N., C. Frost, and R. Marre. 2001. Detection of legionellae in hospital water samples by quantitative real-time LightCycler PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3985-3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]