Abstract

A total of 54 Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains including pandemic O3:K6 strains and newly emerged O4:K68, O1:K25, O1:K26, and O1:K untypeable strains (collectively referred to as the “pandemic group”) were examined for their pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) profiles and for the presence or absence of genetic marker DNA sequences, toxRS/new or orf8, that had been reported elsewhere to be specific for the pandemic group. Both PFGE and AP-PCR analyses indicated that all strains of the pandemic group formed a distinct genotypic cluster, suggesting that they originated from the same clone. In addition to the pandemic group, four O3:K6 strains that did not possess the thermostable direct hemolysin (tdh) gene also belonged to this cluster and possessed the toxRS/new sequence. However, three O3:K6 strains that clearly belonged to the pandemic group by PFGE and AP-PCR did not possess the orf8 sequence. The evidence suggests that neither the toxRS/new nor the orf8 sequence is a reliable gene marker for definite identification of the pandemic group. We therefore developed a novel multiplex PCR assay specific for the pandemic group. The assay successfully distinguished pandemic group strains from other V. parahaemolyticus strains by yielding two distinct PCR products for tdh (263 bp) and the toxRS/new sequence (651 bp).

Vibrio parahaemolyticus causes one of the major forms of seafood-borne gastroenteritis, often associated with the consumption of raw or undercooked seafood (4). Past epidemiological studies (7, 8, 14) revealed a strong association between the thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH) and another hemolysin termed TDH-related hemolysin (TRH), which are produced by members of V. parahaemolyticus, and its pathogenicity. Both hemolysins are thus considered major virulence factors of V. parahaemolyticus. The structural genes for the hemolysins, tdh and trh, respectively, are encoded chromosomally; and PCR-based methods for the detection of the genes have been successfully developed (16, 19). V. parahaemolyticus can be classified into 13 O serotypes and 71 K serotypes (9). Although various serovars of the bacterium can cause infections, O3:K6 has been recognized as the predominant serovar responsible for most outbreaks worldwide since 1996 (5, 13, 17).

Past molecular studies based on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (1, 20) and arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) (13, 17) revealed that those pandemic strains and other recently emerged serovars such as O4:K68 and O1:K untypeable (O1:KUT) showed almost identical fragment patterns, suggesting that these strains are clonally related and form what is referred to as the “pandemic group.” Furthermore, Matsumoto et al. (13) reported that the members of the pandemic group exhibit a unique sequence within the toxRS operon which encodes transmembrane proteins in the regulation of virulence-associated genes conserved in the genus Vibrio. However, we have recently shown that not only the pandemic group but also several PFGE-untypeable TDH-nonproducing O3:K6 strains were positive for the toxRS sequence (18). Meanwhile, Nasu et al. (15) isolated filamentous phage possessing a unique open reading frame, orf8, from a pandemic strain. Moreover, Iida et al. (10) also found orf8 in another recently emerging serovar (i.e., O4:K68), claiming that orf8 is a useful genetic marker for the pandemic group. Nevertheless, Bhuiyan et al. (3) reported that they did not detect orf8 in several O3:K6 strains clinically isolated between 1998 and 2000. These findings suggest that neither the toxRS nor the orf8 sequence is specific enough to distinguish the pandemic group. A more reliable genetic maker is therefore sought. Here we describe the molecular profiles of the pandemic group through PFGE and AP-PCR and reevaluate the use of the genetic markers described above. On the basis of the results obtained, we have developed a multiplex PCR-based assay for the successful identification of pandemic group strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 54 strains of V. parahaemolyticus with known serological identities that had been isolated from various sources were used in the present study and are listed in Table 1. These included 34 strains of O3:K6 consisting of 17 strains isolated before 1996 and 17 strains isolated after 1996, 6 strains of O4:K68 isolated after 1998, 3 strains belonging to O1:KUT, 3 strains belonging to O1:K25, and another 8 strains belonging to diverse serotypes, as listed in Table 1. The strains were maintained on heart infusion agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing NaCl (final concentration, 2%) until use.

TABLE 1.

V. parahaemolyticus isolates used in this study

| Group and strain no. | Serotype | Yr of isolation | Country of isolation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3:K6, isolated since 1996 | ||||

| KE10495 | O3:K6 | 1996 | Japan | Human |

| KE10457 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Japan | Human |

| KE10472 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Japan | Human |

| KE10481 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Japan | Human |

| KE10484 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Japan | Human |

| KE10524 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Japan | Seawater |

| KE10527 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Japan | Food |

| KE10531 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Japan | Human |

| NIID 956-98 | O3:K6 | 1998 | USA | Human |

| NIID K7 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Japan | Human |

| AN-2416 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AN-7410 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AN-8373 | O3:K6 | 1998 | Bangladesh | Human |

| NIID 59-99 | O3:K6 | 1999 | Thailand | Human |

| AO-97 | O3:K6 | 1999 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AP-9251 | O3:K6 | 2000 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AP-14861 | O3:K6 | 2000 | Bangladesh | Human |

| O3:K6, isolated before 1996 | ||||

| KE9967 | O3:K6 | 1981 | Japan | Human |

| KE9971 | O3:K6 | 1981 | Japan | Food |

| KE9984 | O3:K6 | 1981 | Japan | Human |

| KE10461 | O3:K6 | 1982 | Japan | Seawater |

| KE10491 | O3:K6 | 1983 | Japan | Human |

| KE10492 | O3:K6 | 1984 | Japan | Human |

| KE10465 | O3:K6 | 1985 | Japan | Human |

| KE10462 | O3:K6 | 1986 | Japan | Food |

| KE10463 | O3:K6 | 1987 | Japan | Food |

| KE10464 | O3:K6 | 1988 | Japan | Food |

| KE10443 | O3:K6 | 1995 | Japan | Human |

| KE10466 | O3:K6 | 1995 | Japan | Human |

| TVP 1919 | O3:K6 | Before 1996 | Japan | Human |

| TVP 1908 | O3:K6 | Before 1996 | Japan | Human |

| TVP 1841 | O3:K6 | Before 1996 | Japan | Human |

| TVP 1499 | O3:K6 | Before 1996 | Japan | Human |

| TVP 1894 | O3:K6 | Before 1996 | Japan | Human |

| Other serovars | ||||

| AN-2189 | O4:K68 | 1998 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AN-11127 | O4:K68 | 1998 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AN-14142 | O4:K68 | 1998 | Bangladesh | Human |

| KE10545 | O4:K68 | 1999 | Indonesia | Human |

| NIID 181-99 | O4:K68 | 1999 | Thailand | Human |

| NIID 242-200 | O4:K68 | 2000 | Korea | Human |

| AN-16000 | O1:KUT | 1998 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AP-11243-2 | O1:KUT | 2000 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AP-32241 | O1:KUT | 2000 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AO-24491 | O1:K25 | 1999 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AP-18000 | O1:K25 | 2000 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AP-18296 | O1:K25 | 2000 | Bangladesh | Human |

| AP-11243-1 | O1:K26 | 2000 | Bangladesh | Human |

| KE10471 | O4:K6 | 1997 | Japan | Human |

| KE10460 | O3:K56 | 1998 | Japan | Human |

| KE10538 | O4:K8 | 1999 | Thailand | Human |

| KE10540 | O3:K46 | 1999 | Thailand | Human |

| KE10541 | O8:K41 | 1999 | Thailand | Human |

| KE10542 | O3:K48 | 1999 | Thailand | Human |

| KE10579 | O1:K1 | 2000 | Japan | Seawater |

PFGE.

PFGE typing of strains was performed with genomic DNAs digested with the restriction enzyme NotI, as described elsewhere (12), with minor modifications. Briefly, bacterial cells on 2% NaCl heart infusion agar (Difco) were directly embedded in low-melting-temperature agarose (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine). The DNAs in each plug were then digested with 30 U of NotI (Takara Shuzo, Tokyo, Japan) at 37°C for 7.5 h. PFGE was performed with a 1% agarose gel (L03; Takara) on a CHEF DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) in 0.5× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer at 14°C and 200 V. Electrophoresis was performed for 18 h at 6 V/cm with a 2- to 40-s linear ramp time. After PFGE, the gels were stained with ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml) and were photographed under UV transillumination.

DNA preparation.

For subsequent PCR-based assays, the whole genomic DNAs of the strains were prepared in Tris-EDTA buffer (TE; pH 8.0) essentially as described elsewhere (2). The purity and the amount of DNA in each preparation were estimated colorimetrically, and the DNAs were stored at 4°C until use.

AP-PCR.

AP-PCR was performed with the genomic DNAs essentially by the method described by Okuda et al. (17). An oligonucleotide primer, primer 2 (5′-GTTTCGCTCC-3′), provided with the Ready-To-Go RAPD analysis kit (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, N.J.), is used with this method. The PCR mixture was heated at 95°C for 4 min prior to 45 cycles of PCR amplification in a DNA thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR System 2700; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.); one PCR cycle consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 36°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min; after the last cycle, the PCR mixtures were incubated at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed in a 2.0% agarose gel and were visualized by UV illumination for specifically amplified fragments after ethidium bromide staining.

Similarities among PFGE and AP-PCR patterns.

The PFGE and AP-PCR patterns were converted to PICT files and entered into the GelComparII program (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) to generate a dendrogram based on the Dice coefficient (6) by using the unweighted pair group method with 1% position tolerance.

tdh and trh assays.

The presence of tdh and trh in the strains was determined by PCR with a set of primers for tdh, 5′-GGTACTAAATGGCTGACATC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCACTACCACTCTCATA-TGC-3′ (antisense), and another set of primers for trh, 5′-GGCTCAAAATGGTTAAGCG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CATTTCCG-CTCTCATATGC-3 (antisense), by the protocols established by Tada et al. (19).

toxRS-targeted PCR.

PCR was performed as described by Matsumoto et al. (13) with the genomic DNAs of the strains in order to detect the toxRS sequence of the new O3:K6 clone (toxRS/new) and that of the old O3:K6 clone (toxRS/old) with primers 5′-TAATGAGGTAGAAACA-3′ (primer GS-V1) (13) and 5′-ACGTAACGGGCCTACA-3′ (primer GS-V2) (13) and primers 5′-TAATGAGGTAGAAACG-3′ and 5′-ACGTAACGGGCCTACG-3′, respectively.

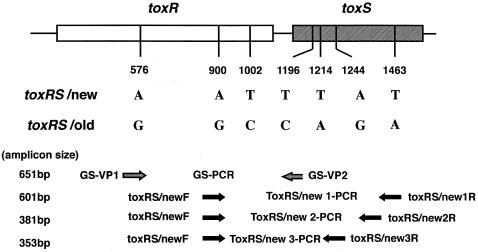

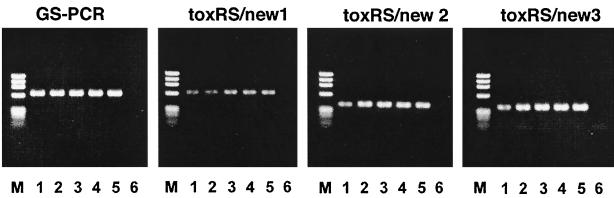

As reported previously (18), four tdh-negative O3:K6 strains produced the PCR amplicon specific for toxRS/new. It was thus necessary to confirm whether the strains indeed possessed the unique DNA sequence. We therefore designed three additional sets of primers to amplify the sequences containing other group-specific bases described by Matsumoto et al. (13) (toxRS/new 1, 2, and 3; Fig. 1). The three primer sets used the sequence 5′-ACTCGTTACCAGTGGAAGTA-3′ (primer toxRS/newF; positions 881 to 900 in the work of Lin et al. [11]; GenBank accession no. L11929) as a sense primer and the sequences 5′-AATTCGGCGGCTTTGTTCA-3′ (primer toxRS/new1R; positions 1481 to 1463 in the work of Lin et al. [11]; GenBank accession no. L11929), 5′-ATGTAATCGCCATTCGGT-3′ (primer toxRS/new2R; positions 1261 to 1244 in the work of Lin et al. [11]; GenBank accession no. L11929), and 5′-CGTTCGACTCCACATTCACA-3′ (primer toxRS/new3R′; positions 1233 to 1214 in the work of Lin et al. [11]; GenBank accession no. L11929) as the three antisense primers, respectively. PCR amplification was then performed in a DNA thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR System 2700; Applied Biosystems) with the genomic DNAs of all strains by the methodology described by Matsumoto et al. (13), except that the annealing temperature was 47°C instead of 45°C. The PCR products were electrophoresed in a 1.5% agarose gel, and after ethidium bromide staining, the specifically amplified fragments were visualized by UV illumination.

FIG. 1.

Target positions of the PCR primers used to amplify the toxRS/new and the toxRS/old sequences with essential base differences. Numerals indicate the base positions that correspond to those in the toxRS sequence of strain AQ3815 reported by Lin et al. (11) (GenBank accession no. L11929). The figure was drawn with reference to Fig. 1 of Matsumoto et al. (13).

orf8- and other orf-targeted PCR.

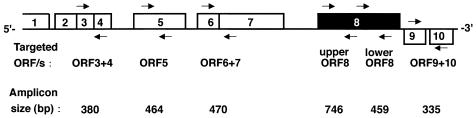

A PCR amplification (10) which is designed to amplify a partial DNA sequence of orf8 (upper orf8 in Fig. 2) was performed with the genomic DNAs by using a set of primers, 5′-GTTCGCATACAGTTGAGG-3′ (primer ORF8A) and 5′-AAGTACAGCAGGAGTGAG-3′ (primer ORF8B). In the present study, three tdh-positive O3:K6 strains whose PFGE fragment patterns belonged to that of the pandemic clone did not produce any amplicon by the orf8-targeted PCR. In order to determine whether the strains had lost the phage encoding orf8 entirely, we performed PCRs with five additional sets of primers that were designed to amplify different parts of orf8 or other orf genes of the lysogenized phage genome (Fig. 2). The primer sets that were designed by referring to the work of Nasu et al. (15) (GenBank accession no. AP000581) were as follows: 5′-CGTCGTTAACCAGTATGGCAA-3′ (primer ORF3 + 4/F) and 5′-TTAGCTTGACCACCGGATACC-3′ (primer ORF3 + 4/R) for partial amplification of the sequence including open reading frames (ORFs) 3 and 4; 5′-ACCCATCATTCCACCGGATA-3′ (primer ORF5/F) and 5′-CACCAAGCCCTTTTAAATCG-3′ (primer ORF5/R) for partial amplification of ORF 5; 5′-TGCTCGAAGAATATGGCGT-3′ (primer ORF6 + 7/F) and 5′-AAACCT-GCATTGACCGAGAA-3′ (primer ORF6 + 7/R) for partial amplification of the sequence including ORFs 6 and 7; 5′-GGGACTTTAAAGAAACAACGA-3′ (primer ORF8C) and 5′-TGCTTCTTCTAGCGATAATCC-3′ (primer ORF8D) for partial amplification of sequence of ORF8 (primer lower ORF8); and 5′-TATCCCATTCTTTGACCGTCC-3′ (primer ORF9 + 10/F) and 5′-AAAGCAAAAACGCACGAAGC-3′ (primer ORF9 + 10/R) for partial amplification of the sequence including orf9 and orf10. PCR amplification was then performed in a DNA thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR System 2700; Applied Biosystems) with the genomic DNAs of all strains by the methodology described by Iida et al. (10), with slight modifications, in which the annealing temperature, the extension time, and the PCR cycles were set at 60°C, 30 s, and 25 cycles, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Target positions of the PCR primers used to amplify the ORF genes specific for the pandemic group. The numerals in the blocks denote ORF numbers. See the text for the base positions of the primers. The figure was drawn with reference to the ORFs of pO3K6 in Fig. 2 of Nasu et al. (15).

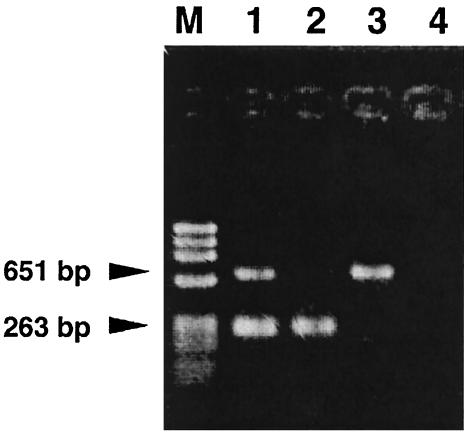

Pandemic group-specific multiplex PCR with primer sets targeting tdh and toxRS/new.

As will be shown below, strains giving positive PCR results for both tdh and toxRS/new were found to belong to the pandemic group. In this context, we developed a novel multiplex PCR targeting both gene markers. The oligonucleotide primers used in the multiplex PCR were 5′-TGACTGTGAACATTAATGA-3′ (sense primer) and 5′-CGATTCTTTGTTGGATATAC-3′(antisense primer), which are specific for positions 451 to 469 and 713 to 694 in tdh, respectively (position numbers are according to Honda et al. [8]; GenBank accession no. D90238), and which yield a 263-bp fragment, and 5′-TAATGAGGTAGAAACG-3′ (sense primer) and 5′-ACGTAACGGGCCTACA-3′(antisense primer), which are specific for positions 561 to 576 and 1211 to 1196 in toxRS/new, respectively (position numbers are according to Lin et al. [11]; GenBank accession no. L11929), and which yield a 651-bp fragment. PCR amplification was performed in a total volume of 20 μl. Two microliters of each genomic DNA preparation (1 ng of DNA/μl of TE) was added to the PCR master mixture, which consisted of 2 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Mg2+ free; Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.), 2.4 μl of 25 mM MgCl2 (final concentration, 3.0 mM), 0.25 μl of a deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture (0.125 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate), 0.125 μl of each primer (0.125 μM each primer), and 0.125 μl (0.625 U) of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega), with the remaining volume consisting of distilled water. A GeneAmp PCR System 2700 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) was used for PCR amplification, which consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min; 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 45°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 60 s; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Five microliters of the PCR products was electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide (0.25 μg/ml), and photographed under UV light.

RESULTS

Genotypes determined by PFGE.

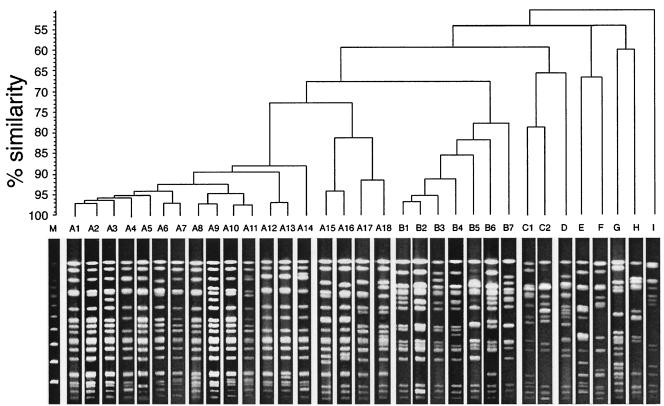

A total of 33 PFGE patterns were observed with the strains examined (Fig. 3). Software analysis of the PFGE profiles revealed the presence of nine distinct genotypes (genotypes A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and I) at the 70% similarity level (Fig. 3). PFGE type A could be further subdivided into two clusters at the 75% similarity level. One cluster consisted of 14 patterns (patterns A1 to A14) for the tdh-positive O3:K6, O4:K68, O1:K25, O1:K26, and O1:KUT strains isolated since 1996; and the other cluster consisted of 4 patterns (patterns A15 to A18) for the tdh-negative O3:K6 strains isolated in the 1980s (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The strains with the patterns assigned to type B that were indistinguishable from the strains with type A patterns at the 65% similarity level included the tdh-negative O3:K6 strains isolated in the 1980s and the trh-positive O3:K6 strains (Fig. 3 and Table 2).

FIG. 3.

Representative PFGE patterns for V. parahaemolyticus genomic DNAs digested with NotI and dengrogram illustrating the clustering of patterns by percent similarity (shown at the left of the dendrogram). Lane M, molecular size marker (bacteriophage lambda ladder PFG Marker; New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.).

TABLE 2.

Genotypic characteristics of V. parahaemolyticus isolates

| Group and strain no. | Serotype | Genotype determined by:

|

Results of PCR targeting the following gene(s)c:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFGEa | AP-PCRb | tdh | trh | toxRS/new | toxRS/old | orf8 | tdh and toxRS/newd | ||

| O3:K6, isolated since 1996 | |||||||||

| KE10495 | O3:K6 | A2 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| KE10457 | O3:K6 | A1 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| KE10472 | O3:K6 | A1 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| KE10481 | O3:K6 | A1 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| KE10484 | O3:K6 | A8 | a2 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| KE10524 | O3:K6 | A9 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| KE10527 | O3:K6 | A3 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| KE10531 | O3:K6 | A1 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| NIID 956-98 | O3:K6 | A5 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| NIID K7 | O3:K6 | A1 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AN-2416 | O3:K6 | A1 | a1 | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| AN-7410 | O3:K6 | A1 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AN-8373 | O3:K6 | A6 | a1 | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| NIID 59-99 | O3:K6 | A10 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AO-97 | O3:K6 | A1 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AP-9251 | O3:K6 | A6 | a3 | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| AP-14861 | O3:K6 | A1 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| O3:K6, isolated before 1996 | |||||||||

| KE9967 | O3:K6 | B7 | d3 | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| KE9971 | O3:K6 | B7 | d3 | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| KE9984 | O3:K6 | B1 | c1 | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| KE10461 | O3:K6 | G | f | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| KE10491 | O3:K6 | A18 | a4 | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| KE10492 | O3:K6 | B6 | c1 | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| KE10465 | O3:K6 | A16 | a4 | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| KE10462 | O3:K6 | A17 | a4 | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| KE10463 | O3:K6 | B5 | c1 | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| KE10464 | O3:K6 | A15 | a4 | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| KE10443 | O3:K6 | B1 | c1 | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| KE10466 | O3:K6 | B2 | c1 | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| TVP 1919 | O3:K6 | B1 | c1 | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| TVP 1908 | O3:K6 | B1 | c1 | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| TVP 1841 | O3:K6 | B4 | c1 | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| TVP 1499 | O3:K6 | B3 | c1 | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| TVP 1894 | O3:K6 | B3 | c1 | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| Other serovars | |||||||||

| AN-2189 | O4:K68 | A7 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AN-11127 | O4:K68 | A7 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AN-14142 | O4:K68 | A7 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| KE10545 | O4:K68 | A7 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| NIID 181-99 | O4:K68 | A11 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| NIID 242-200 | O4:K68 | A7 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AN-16000 | O1:KUT | A12 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AP-11243-2 | O1:KUT | A12 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AP-32241 | O1:KUT | A13 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AO-24491 | O1:K25 | A4 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AP-18000 | O1:K25 | A4 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AP-18296 | O1:K25 | A14 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| AP-11243-1 | O1:K26 | A12 | a1 | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| KE10471 | O4:K6 | E | e | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| KE10460 | O3:K56 | I | c3 | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| KE10538 | O4:K8 | H | c2 | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| KE10540 | O3:K46 | C1 | d1 | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| KE10541 | O8:K41 | D | d4 | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| KE10542 | O3:K48 | C2 | d2 | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| KE10579 | O1:K1 | F | b | + | + | − | + | − | − |

Genotypes determined by AP-PCR.

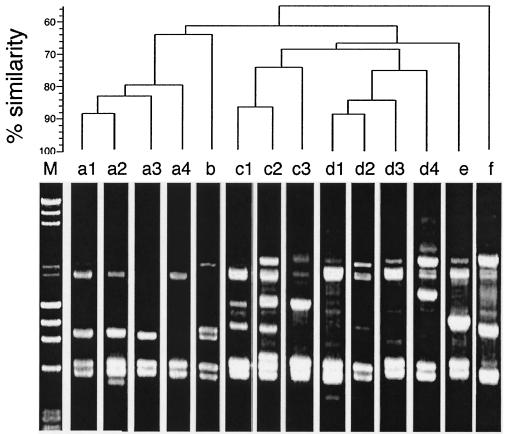

A total of 14 AP-PCR patterns were observed among the strains examined (Fig. 4). Software analysis of the profiles distinguished six distinct genotypes (genotypes a, b, c, d, e, and f at the 70% similarity level) (Fig. 4). The AP-PCR patterns designated type a consisted of four patterns (patterns a1, a2, a3, and a4) for the tdh-positive O3:K6, O4:K68, O1:K25, O1:K26, and O1:KUT strains isolated since 1996 and the four tdh-negative O3:K6 strains isolated in the 1980s (Fig. 4 and Table 2), all of which belonged to PFGE type A, as described above.

FIG. 4.

Representative AP-PCR patterns for V. parahaemolyticus genomic DNAs and dendrogram illustrating the clustering of patterns by percent similarity (shown at the left of the dengrogram). Lane M, molecular size marker (a mixture of phage λ DNA digested with HindIII and phage φX174 DNA digested with HaeIII).

Prevalence of conventional gene markers specific to the pandemic group.

The presence or absence of toxRS/new, toxRS/old, and orf8 in the strains determined by the PCR-based assays is shown in Table 2. The toxRS/new sequence was detected in all strains belonging to PFGE type A or AP-PCR type a, while the rest of the strains were found to possess the toxRS/old sequence. The toxRS/new-positive strains included the four tdh-negative O3:K6 strains (strains KE10462, KE10464, KE10465, and KE10491) isolated in the 1980s. Subsequent PCR-based analyses with primer sets targeting different sites specific for the toxRS/new sequence revealed that those tdh-negative O3:K6 strains possessed the whole sequence (Fig. 5). The orf8 gene was detected in all O3:K6 strains belonging to PFGE type A or AP-PCR type a except for the three tdh- and toxRS/new-positive strains (strains AN-2416, AN-8373, and AP-9251) that had been isolated from clinical cases in Bangladesh between 1998 and 2000 and the four tdh-negative O3:K6 strains (strains KE10462, KE10464, KE10465, and KE10491). These orf8-negative strains were further assayed by the PCR methods targeting other ORF genes and were found to be devoid of all ORF sequences (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Agarose gel electrophoresis showing the results of four different PCR amplifications (with the GS, toxRS/new1, toxRS/new2, and toxR/new3 sets of primers) targeting toxRS/new. Lanes M, molecular size markers (phage φX174 DNA digested with HaeIII); lanes 1, NIID 956-98 (O3:K6, isolated after 1996) as a positive control; lanes 2, KE10491 (O3:K6, isolated before 1996); lanes 3, KE10465 (O3:K6, isolated before 1996); lanes 4, KE10462 (O3:K6, isolated before 1996); lanes 5, KE10464 (O3:K6, isolated before 1996); lanes 6, KE 9967 (O3:K6, isolated before 1996) as a negative control. See Fig. 1 for the primer positions and the amplicon size for each PCR.

Evaluation of multiplex PCR assay.

We subsequently analyzed the strains by the multiplex PCR assay targeting both tdh and toxRS/new. All PFGE type A (or AP-PCR type a) strains except the four toxRS/new-positive and tdh-negative O3:K6 strains (strains KE10462, KE10464, KE10465, and KE10491) gave the toxRS/new-specific amplicon of 651 bp as well as the tdh-specific amplicon of 263 bp, while other strains failed to produce either or both amplicons (Fig. 6 and Table 2).

FIG. 6.

Agarose gel electrophoresis showing the representative results of multiplex PCR amplification targeting tdh and toxRS/new. The PCR amplicon sizes for tdh and toxRS/new are 263 and 651 bp, respectively. Lane M, molecular size marker (phage φX174 DNA digested with HaeIII); lane 1, NIID 956-98 (O3:K6, isolated after 1996; tdh positive, toxRS/new positive); lane 2, KE9967 (O3:K6, isolated before 1996; tdh positive, toxRS/new negative); lane 3, KE10462 (O3:K6, isolated before 1996; tdh negative, toxRS/new positive); lane 4, KE10460 (O3:K56; tdh negative, toxRS/new negative).

DISCUSSION

Our PFGE analysis of V. parahaemolyticus strains revealed that the tdh-positive strains of O3:K6, O4:K68, O1:K25, O1:K26, and O1:KUT isolated since 1996 (collectively referred to as the “pandemic group”) were all within a distinct genotypic cluster that included 14 PFGE profiles (A1 to A14). It is noteworthy that many Bangladeshi and Japanese O3:K6 strains presented an identical PFGE profile (profile A1), implying some epidemiological linkage between these two countries. The results of our AP-PCR analysis were also consistent with these findings; the pandemic strains formed a homogeneous cluster distinct from any of the other strains. This evidence supports the view presented by other workers (1, 13, 17, 20) that the pandemic group might have originated from the same clone. However, both analyses indicated that the four tdh-negative O3:K6 strains isolated well before 1996 were included in the pandemic strain cluster (>75% similarity level), although their PFGE profiles (profile A15 to A18) were slightly distant from those of the pandemic strains. Furthermore, our PCR test indicated that the strains possessed toxRS/new. These findings suggest that the presence of the toxRS/new sequence is not a newly emerged genetic profile in members of the species V. parahaemolyticus. The pandemic group might have stemmed from those nonpathogenic strains with toxRS/new after acquisition of the tdh gene, although this hypothesis is highly speculative. Meanwhile, the PCR assays targeting orf8 and other ORFs that were reportedly encoded by the genome of a filamentous bacteriophage specifically lysogenized in the pandemic strains (15) failed to produce any amplicon from several strains of the pandemic group, indicating that they were not lysogenized by the phage. Whether the strains had been accidentally cured of the phage during laboratory processing has yet to be determined.

On the basis of the results of our investigation, it can be seen that neither toxRS/new nor orf8 is a reliable genetic marker for PCR-based identification of the pandemic strains; detection of toxRS/new is necessary but not always sufficient for the identification of the pandemic strains, while detection of orf8 is sufficient but not always necessary for the identification of pandemic strains. This in turn suggests that a strain possessing both tdh and toxRS/new can be considered a pandemic strain. On this basis, we have developed a novel PCR-based assay for the successful identification of pandemic strains. The assay uses a multiplex PCR designed to amplify either toxRS/new or orf8 or both toxRS/new and orf8 simultaneously, in which only pandemic strains including orf8-negative strains produce two specific fragments. Although the assay needs to be evaluated further for its reliability with more strains of a much wider range of serologies or sources, it can be a useful diagnostic or epidemiological tool for investigating outbreaks of food poisoning caused by V. parahaemolyticus, with specific reference to the pandemic group.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by health science research grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

We thank S. Yamai and T. Okitsu of Kanagawa Prefectural Health Laboratory, H. Matsushita of Tokyo Metropolitan Health Laboratory, and G. B. Nair of the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research for kindly providing us with a part of their culture collection. We are also grateful to R. A. Whiley of the Department of Oral Microbiology, St. Bartholomew's and Royal London School of Medicine and Dentistry, for valuable comments on an earlier draft of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakawa, E., T. Murase, T. Shimada, T. Okitsu, S. Yamai, and H. Watanabe. 1999. Emergence and prevalence of novel Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 clone in Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 52:246-247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bej, A. K., D. P. Patterson, C. W. Brasher, M. C. Vickery, D. D. Jones, and C. A. Kaysner. 1999. Detection of total and hemolysin-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish using multiplex PCR amplification of tl, tdh and trh. J. Microbiol. Methods 36:215-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhuiyan, N. A., M. Ansaruzzaman, M. Kamruzzaman, K. Alam, N. R. Chowdhury, M. Nishibuchi, S. M. Faruque, D. A. Sack, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2002. Prevalence of the pandemic genotype of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and significance of its distribution across different serotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:284-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blake, P. A., R. E. Weaver, and D. G. Hollis. 1980. Disease of humans (other than cholera) caused by vibrios. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 34:341-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1998. Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections associated with eating raw oysters and clams harvested from Long Island Sound—Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. JAMA 281:603-604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dice, L. R. 1945. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology 26:297-302. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honda, T., Y. Ni, and T. Miwatani. 1988. Purification and characterization of a hemolysin produced by a clinical isolate of Kanagawa phenomenon-negative Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related to the thermostable direct hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 56:961-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honda, T., M. A. Abad-Lapuebla, Y. X. Ni, K. Yamamoto, and T. Miwatani. 1991. Characterization of a new thermostable direct haemolysin produced by a Kanagawa-phenomenon-negative clinical isolate of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:253-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iguchi, T., S. Kondo, and K. Hisatune. 1995. Vibrio parahaemolyticus O serotypes from O1 to O13 all produce R-type lipopolysaccharide: SDS-PAGE and compositional sugar analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 130:287-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iida, T., A. Hattori, K. Tagomori, H. Nasu, R. Naim, and T. Honda. 2001. Filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:477-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin, Z., K. Kumagai, K. Baba, J. J. Mekalanos, and M. Nishibuchi. 1993. Vibrio parahaemolyticus has a homolog of the Vibrio cholerae toxRS operon that mediates environmentally induced regulation of the thermostable direct hemolysin gene. J. Bacteriol. 175:3844-3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall, S., C. G. Clark, G. Wang, M. Mulvey, M. T. Kelly, and W. M. Johnson. 1999. Comparison of molecular methods for typing Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2473-2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto, C., J. Okuda, M. Ishibashi, M. Iwanaga, P. Garg, T. Rammamurthy, H.-C. Wong, A. DePaola, Y. B. Kim, M. J. Albert, and M. Nishibuchi. 2000. Pandemic spread of an O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and emergence of related strains evidenced by arbitrarily primed PCR and toxRS sequence analyses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:578-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyamoto, Y., T. Kato, Y. Obara, S. Akiyama, K. Takizawa, and S. Yamai. 1969. In vitro hemolytic characteristic of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: its close correlation with human pathogenicity. J. Bacteriol. 100:1147-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nasu, H., T. Iida, T. Sugahara, Y. Yamaichi, K.-S. Park, K. Yokoyama, K. Makino, H. Shinagawa, and T. Honda. 2000. A filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2156-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuda, J., M. Ishibashi, S. L. Abbott, J. M. Janda, and M. Nishibuchi. 1997. Analysis of the thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH) gene and the TDH-related hemolysin (trh) genes in urease-positive strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated on the West Coast of the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1965-1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okuda, J., M. Ishibashi, E. Hayakawa, T. Nishino, Y. Takeda, A. K. Mukhopadhyay, S. Garg, S. K. Bhattacharya, G. B. Nair, and M. Nishibuchi. 1997. Emergence of a unique O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Calcutta, India, and isolation of strains from the same clonal group from Southeast Asian travelers arriving in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3150-3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osawa, R., A. Iguchi, E. Arakawa, and H. Watanabe. 2002. Genotyping of pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 still open to question J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2708-2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tada, J., T. Ohashi, N. Nishimura, Y. Shirasaki, H. Ozaki, S. Fukushima, J. Takano, M. Nishibuchi, and Y. Takeda. 1992. Detection the thermostable direct hemolysin gene (tdh) and the thermostable direct hemolysin-related hemolysin gene (trh) of Vibrio parahaemolyticus by polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Cell. Probes 6:477-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong, H.-C., S.-H. Liu, T.-K. Wang, C.-L. Lee, C.-S. Chiou, D.-P. Liu, M. Nishibuchi, and B.-K. Lee. 2000. Characteristics of Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 from Asia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3981-3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]