Abstract

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) occurs normally during carcinoma invasion and metastasis, but not during early tumorigenesis. Microarray data demonstrated elevation of vimentin, a mesenchymal marker, in intestinal adenomas from ApcMin/+ (Min) mice. We have tested the involvement of EMT in early tumorigenesis in mammalian intestines by following EMT-associated markers. Elevated vimentin RNA expression and protein production were detected within neoplastic cells in murine intestinal adenomas. Similarly, vimentin protein was detected in both adenomas and invasive adenocarcinomas of the human colon, but not in the normal colonic epithelium or in hyperplastic polyps. Expression of E-cadherin varied inversely with vimentin. In addition, the expression of fibronectin was elevated while that of E-cadherin decreased. Canonical E-cadherin suppressors, such as Snail, were not elevated in the same tumor. Elevated vimentin expression in the adenoma was not correlated with persistent Ras signaling, but was strongly correlated with reduced proliferation indices, active Wnt signaling, and TGF-β signaling, as demonstrated by its dependence on Smad3. We designate our observations of expression of only some of the canonical features of EMT as “truncated EMT”. These unexpected observations are interpreted as reflecting the involvement of a core of the EMT system during the tissue remodeling of early tumorigenesis.

Keywords: vimentin, ApcMin, intestinal adenoma, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition, E-cadherin

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer remains a major life-threatening cancer in the Western world. More than 52,000 people in the United States will die of this cancer in 2007 (American Cancer Society 2007). Although the burden of this disease has been substantially reduced by the early detection of benign colonic adenomas (Smith et al. 2001), treatments are very ineffective against invasive and metastatic colonic tumors. Since most, if not all, cancer deaths, are caused by metastasis (Sporn 1996), it is important to elucidate the mechanisms involved in tumor invasion and metastasis.

Loss of wild-type Apc function is the most frequent mutational event in human colon cancer (Wood et al. 2007). Animal models for intestinal neoplasia, such as the ApcMin mouse model (Moser et al. 1990) and the ApcPirc rat model (Amos-Landgraf et al. 2007), involve germline mutations in the Apc gene. Neoplastic cells undergo a series of changes in morphology and gene expression as colorectal adenomas progress to invasive adenocarcinomas (Hanahan and Weinberg 2000). One major change is the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Gotzmann et al. 2004; Bates and Mercurio 2005). In this process, neoplastic cells lose common epithelial features, including cell polarity, adhesion junctions between adjacent cells, and well-organized cell layers. At the same time, these cells acquire mesenchymal features such as cell motility and plasticity. In addition, these morphological transitions are accompanied by the loss of epithelium-associated markers, such as E-cadherin, and a gain of mesenchymal proteins, including vimentin and fibronectin (Yang et al. 2004). The EMT process, first identified in embryonic development (Greenburg and Hay 1982), is now considered by some to be a critical event for the invasion and metastasis of epithelial tumors (Savagner 2001; but see Tarin et al. 2005 and Christiansen and Rajasekaran 2006). The morphological alterations during EMT would allow neoplastic cells to escape from the epithelial cohort and migrate through different tissue barriers to reach neighboring lymph nodes or enter the circulation (Kang and Massague 2004).

The EMT process and EMT-like alterations have been described in human carcinomas of several types (Gotzmann et al. 2004), including breast (Reeves et al. 2001), prostate (Park et al. 2000), pancreas (Menke et al. 2001) and colon (Bates et al. 2005). A number of models have recently been established to study EMT in advanced neoplastic cells (Gotzmann et al. 2004). Because of the difficulty in distinguishing normal mesenchymal cells from those transformed from epithelium by the EMT in the intact animal, most of these models use established cancer cell lines or organotypic cultures in vitro, in which the EMT is generated by exogenous inducers, such as TGF-β (Gotzmann et al. 2004; Bates and Mercurio 2005). Here we report the unexpectedly early appearance of several molecular alterations characteristic of EMT in benign adenomas from an autochthonous mouse intestinal cancer model. This discovery opens the way to the further study of elements of EMT in tissue remodeling in an in vivo setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse maintenance

Mouse colonies were bred and maintained in the AALAC-approved animal facility of the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research. Husbandry and genotyping for ApcMin, Apc1638N and Smad3 was carried out as described previously (Su et al. 1992; Fodde et al. 1994; Zhu et al. 1998).

Tissue collection and preparation

Min mice were euthanized between 65 and 250 days of age. After removal of the colon, tumors were isolated and fixed immediately in RNAlater® stabilization reagent (10 ml/g of wet weight; Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For histology, the tumors from the small intestine, the cecum, and the colon, along with adjacent normal tissues, were isolated, put immediately into 10% formalin solution for overnight fixation and stored in 70% ethanol. Tissues were then dehydrated and processed under RNase-free conditions to produce 5µm paraffin sections on positively-charged slides in the histology facility of the McArdle Laboratory. Tumor sections from Apc1638N/+ (1638N) mice, Smad3-deficient mice and Smad3-deficient Min mice were prepared in the same way. The embedded murine colonic tumors induced by AOM were kindly provided by Dr. David Threadgill at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Human materials

Anonymous archived sections of human colonic tissues were kindly provided by Dr. Jose Torrealba at Department of Pathology, University of Wisconsin at Madison, WI.

RT-PCR and in situ hybridization (ISH)

Gene-specific primers (20 bp) were designed to generate DNA templates to synthesize probes by RT-PCR. These included:

vimentin forward (5′-ATGTCTACCAGGTCTGTGTC-3′),

vimentin reverse (5′-TCCTGCAATTTCTCTCGCAG-3′),

E-cadherin forward (5′-CATCAGTGTGCTCACCTCTG-3′),

E-cadherin reverse (5′-CTCTCGAGCGGTATAAGATG-3′),

fibronectin forward (5′-GTGGAAGTGTGAGCGACATG-3′), and

fibronectin reverse (5′-GATCGGCATCGTAGTTCTGG-3′). The Titan One® RT-PCR system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was used to generate corresponding cDNA fragments with total RNA from colonic tumors according to the manufacturer's protocol. The resulting cDNA fragments were used to generate DNA templates by PCR for probes for ISH. PCR was performed with gene-specific primers with a tag of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter (5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) on the 5′ end of one primer or the other. The resulting templates were gel-purified and transcribed in vitro with T7 polymerase (Roche), using a digoxygenin-labeled NTP mix (Roche) to synthesize cRNA probes (antisense and sense) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The synthesized probes were sized by electrophoresis. Non-radioactive ISH was then performed on paraffin sections as previously described (Chen et al. 2003).

Antibodies and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Antibodies against vimentin (monoclonal biotin-conjugated, clone 3B4, RDI, Flanders, NJ; polyclonal, AbCam, Cambridge, UK), Ki67 (monoclonal, BD Pharmagen, Chicago, IL), phospho-Smad2 (pSmad2; polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), phosphorylated-p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (pMAPK; monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology), Snail (monoclonal, a generous gift from Dr. I. Virtanen of University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland) (Franci et al. 2006), Slug, twist, and ILK (polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Santa Cruz, CA) were used as primary antibodies for immunohistochemistry. The procedure was performed on paraffin sections of mouse and human tumors with the Histostain® Plus (DAB) kit (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For antibodies that did not show expected staining, antigen-retrieval protocols using citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and Tris-HCl buffer (pH 10.5) were tested.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Paraffin sections (5 µm) were dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated in an ethanol:H2O series (100%, 90%, 70%, 50%), and antigen-retrieved by microwaving in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 25 min at full power. Normal goat serum was used to reduce nonspecific binding. Monoclonal antibody against β-catenin (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA; 1:200 dilution) or monoclonal antibody against E-cadherin (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA; 1:100 dilution), and affinity-purified polyclonal antibody against wild-type Apc (serum 3122; 1:100 dilution) or polyclonal antibody against vimentin (AbCam, Cambridge, UK; 1:100) were incubated on sections at 4°C overnight. Excess antibody was removed by washing three times (5 min each) with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST). The secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit FITC, (Invitrogen; 1:200 dilution) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor® 594 (Invitrogen; 1:200 dilution), were then applied for 1 h at room temperature. Excess antibodies were washed away with PBST and sections were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1 µg/ml; Sigma), followed by the addition of coverslips without dehydration.

Statistics

All staining results were scored by the same investigator (XC). The p values were calculated using the two-sided Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

Ectopic expression and production of vimentin in intestinal tumors of Min mice

A study of transcript abundance in colonic tumors conducted in the laboratories of B. Aronow, R. Coffey, T. Doetschman, W. Dove, J. Groden, and D. Threadgill of the Mouse Models for Human Cancer Consortium, has indicated that the expression of vimentin is strongly elevated in colonic tumors of the Min mouse (Kaiser et al. 2007). Vimentin is an established marker for mesenchymal cells (Ngai et al. 1985) and is not expressed in the normal intestinal epithelium. Therefore, we have further investigated the temporal and spatial patterns of vimentin expression during intestinal adenomagenesis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of vimentin expression in murine and human intestinal lesions

| Species | Genotype/carcinogen | Location | Histology | Method* | Vimentin expression† | Positive rate (N of tumors) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | B6 ApcMin/+ | Colon | normal crypts and hyperplastic polyps | ISH | − | 0% (> 100) |

| adenomas | ISH | ++++ | 94% (79) | |||

| microadenomas | ISH | +++ | 100% (3) | |||

| Small intestine | adenomas | ISH | +++ | 79% (57) | ||

| (BR × B6) F1 ApcMin/+ | Colon | adenocarcinomas | IHC | +++ | 100% (2) | |

| B6 Apc1638N | Small intestine | adenomas | ISH | + | 20% (10) | |

| B6 AOM | Colon | adenomas | ISH | ++++ | 83% (12) | |

| BTBR ApcMin/+ | Colon | adenomas | IHC | +++ | 80% (5) | |

| 129 ApcMin/+ | Small intestine | adenomas | IHC | +++ | 82% (11) | |

| 129 Smad3−/− | Colon, cecum | adenomas | IHC | − | 0% (13) | |

| 129 ApcMin/+, Smad3−/− | Small intestine | adenomas | IHC | + | 13% (8) | |

| Human | N/A | Colon | normal crypts and hyperplastic polyps | IHC | − | 0% (7) |

| tubular adenomas | IHC | ++ | 50% (2) | |||

| villous adenomas | IHC | ++ | 50% (4) | |||

| adenocarcinomas | IHC | +++ | 67% (3) | |||

ISH: in situ hybridization; IHC: immunohistochemistry

Vimentin expression levels were estimated by relative intensity and coverage of staining. ++++ represents very strong and widely distributed staining as in Figure 1A +++ represents strong staining with relatively limited coverage as in Figure 1B left panel. ++ represents apparent signals in small numbers of tumors cells as in Figure 2F. + represents barely detectable staining in small numbers of tumor cells as inFigure 3K.– represents no detectable staining as in the lower part of Figure 4A.

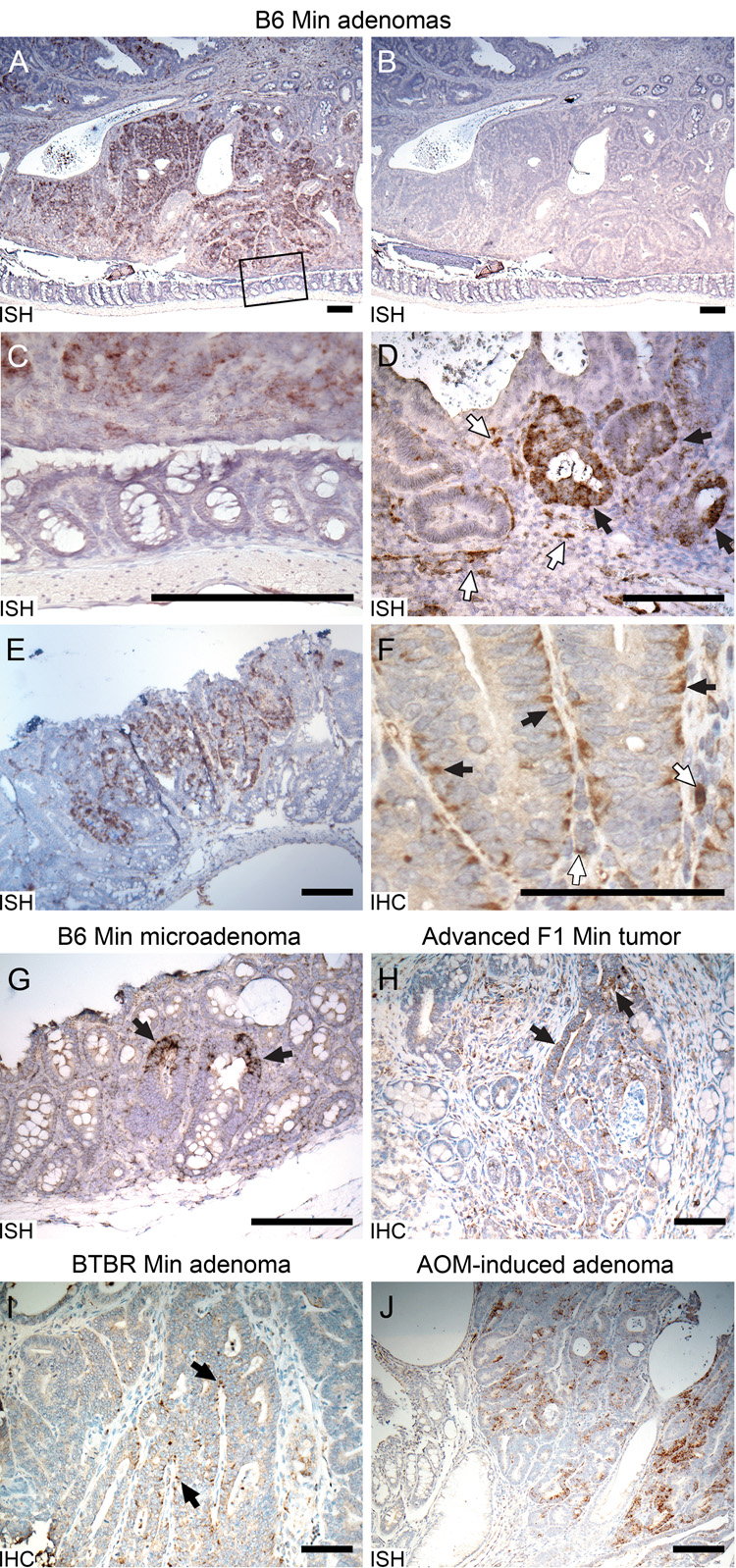

Colonic tumors from C57BL/6J (B6) Min mice were tested for vimentin expression using in situ hybridization (ISH). Strong signals were observed in 74 out of 79 tumors (94%; Figure 1A), but were undetectable in the adjacent normal epithelium (Figure 1C, magnified from the box in 1A). Microscopy at higher magnification revealed that strong vimentin staining was localized to the cytoplasm of colonic neoplastic cells with characteristic epithelial organization (Figure 1D, black arrows). As expected, the expression of vimentin can also be detected in normal mesenchymal cells (Figure 1D, white-filled arrows). Strong expression was also observed in adenomas from the small intestine, although at a lower frequency than in the colon [45 out of 57 (79%) Figure 1E, 79% vs. 94%, p < 0.05].

Figure 1. Expression of vimentin in murine intestinal tumors.

A. Vimentin expression detected in the intestinal adenomas of B6 Min mice at 100d. Very strong vimentin RNA signals (dark brown signals) detected by ISH in a Min colonic adenoma. B. The sense control. C. Magnification of box in upper panel showing no vimentin signal in the adjacent normal epithelium. D. Magnification of the same Min colonic adenoma demonstrating vimentin RNA in some neoplastic cells (black arrows) as well as in mesenchymal cells (white-filled arrows). E. Elevated vimentin RNA detected by ISH within an adenoma from small intestines. F. Vimentin protein detected by IHC in basal and lateral sides of B6 Min neoplastic colonic cells (black arrows) and mesenchymal cells (white-filled arrows). G. Vimentin expression detected by ISH in B6 Min microadenomas (indicated by arrows). H. Vimentin signals detected by IHC in the neoplastic cells (arrows) invaded into submucosa of advanced tumors from (BR × B6) F1 mice. I. Vimentin antigen detected by IHC in BTBR Min colonic neoplastic cells. J. Very strong vimentin expression detected by ISH in colonic tumors induced by AOM. Size bars for panels A–E and G–J, 200 µm. Size bar for panel F, 100 µm.

Immunohistochemistry on colonic tumor sections detected strong protein signals in the same regions where the vimentin RNA was detected. In those neoplastic cells maintaining epithelial morphology, vimentin protein was localized mainly to the basolateral regions of the cytoplasm (Figure 1F black arrows) while mesenchymal cells gave the expected signals (Figure 1F white-filled arrows).

Temporal, biological and spatial patterns of tumor-associated vimentin expression

Intestinal lesions can be defined as hyperplastic polyps, microadenomas, adenomas, or adenocarcinomas. Hyperplastic polyps(Bond 2000) can frequently be found in the colons of Min mice (XC, unpublished observations) but ISH showed that these lack detectable vimentin expression (n = 5, data not shown). By contrast, microadenomas involving only 3–5 crypts in the colon and small intestine have strongly elevated vimentin RNA (3/3 tumors; Figure 1G arrows). Thus, vimentin expression becomes detectable at an early stage of tumorigenesis. These lesions show features typical of adenomas, including enlarged nuclei and dysplasia.

Min mice on the tumor-resistant (C57BR/cdcJ (BR) × B6) F1 genetic background have reduced tumor multiplicities and hence longer life spans. Some mice as old as 250 days develop locally invasive intestinal tumors, reaching into the submucosa and/or musculature layers. In these tumors, immunohistochemistry (IHC) demonstrated strong vimentin expression not only in the epithelia of the primary tumor but also in the neoplastic cells invading the submucosa and muscular layer (2/2 tumors; Figure 1H arrows).

Ectopic vimentin expression was not evenly distributed in all neoplastic cells, but was patchy in tumor sections with varied intensity within a single tumor. These patches were found in both central and peripheral tumor regions.

Vimentin expression is robust to genetic background effects on the Min phenotype

The Min phenotype is dramatically affected by genetic background. On the inbred B6 background, Min mice develop an average of 100 intestinal tumors. On the inbred BTBR/Pas (BTBR) strain, however, the number is nearly 5-fold higher (Kwong et al. 2007), while on the inbred 129S6/SvEvTac (129) strain the number is reduced to about 50 (RBH, unpublished data). On each of these genetic backgrounds vimentin expression is similar: in BTBR.Min, 4/5 tumors, 80%, Figure 1I arrows; in 129 Min 9/11 tumors, 82%, Figure 4B, and B6.Min 74/79, 94% (three pairwise p-values are each greater than 0.05). Thus, vimentin expression is not restricted to the B6 genetic background, but is likely to be a general characteristic of early Min tumorigenesis.

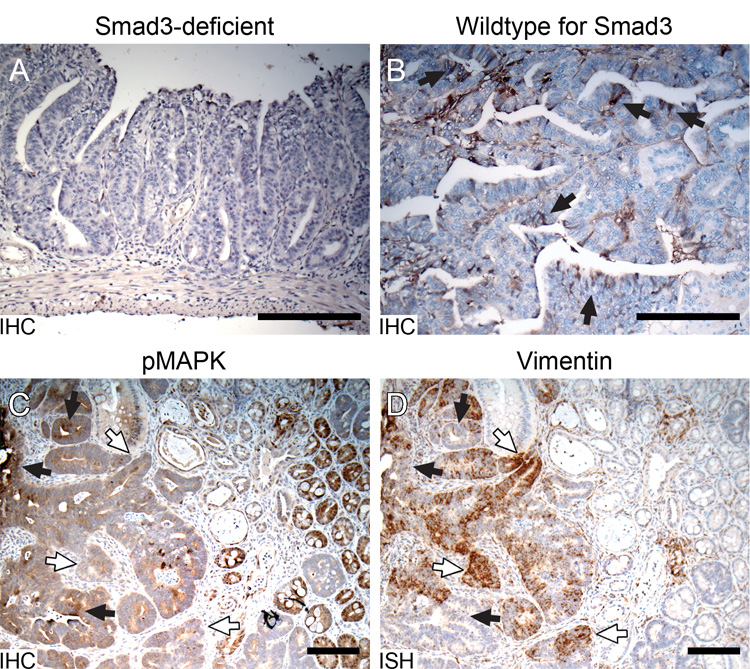

Figure 4. TGF-β and Ras signaling associated with vimentin expression.

A. No vimentin signal detected by IHC in a Smad-3-deficient 129 Min adenoma. B. Vimentin (brown) detected by IHC in a Smad-3 wildtype 129 Min adenoma. Comparison of the Ras signaling pathway indicated by (C) IHC for pMAPK and (D) vimentin expression by ISH in a B6 Min adenoma. Black arrows, regions with strong pMAPK staining and weak vimentin expression. White-filled arrows, regions with weak pMAPK staining and strong vimentin expression. Size bars, 200 µm.

Vimentin expression in murine intestinal tumors induced by azoxymethane (AOM)

Chemical carcinogens have been used to investigate intestinal tumorigenesis in the mouse. The intestinal tumors induced by AOM have been regarded as a model of spontaneous colonic tumors (Takahashi and Wakabayashi 2004). AOM-induced colonic tumors, established on the B6 background by David Threadgill (Chapel Hill), also demonstrate aberrant Wnt signaling in neoplasms (Kaiser et al. 2007). ISH for vimentin detected strong positive signals in AOM-induced colonic tumors (10/12 tumors, 83%, Figure 1J), not significantly different from colonic tumors in Min mice (83% vs. 94%, p > 0.2). The expression pattern of vimentin in AOM-induced tumors was quite similar to that in Min colonic tumors. Thus, ectopic production of vimentin is not restricted to the familial intestinal adenomas of Min mice.

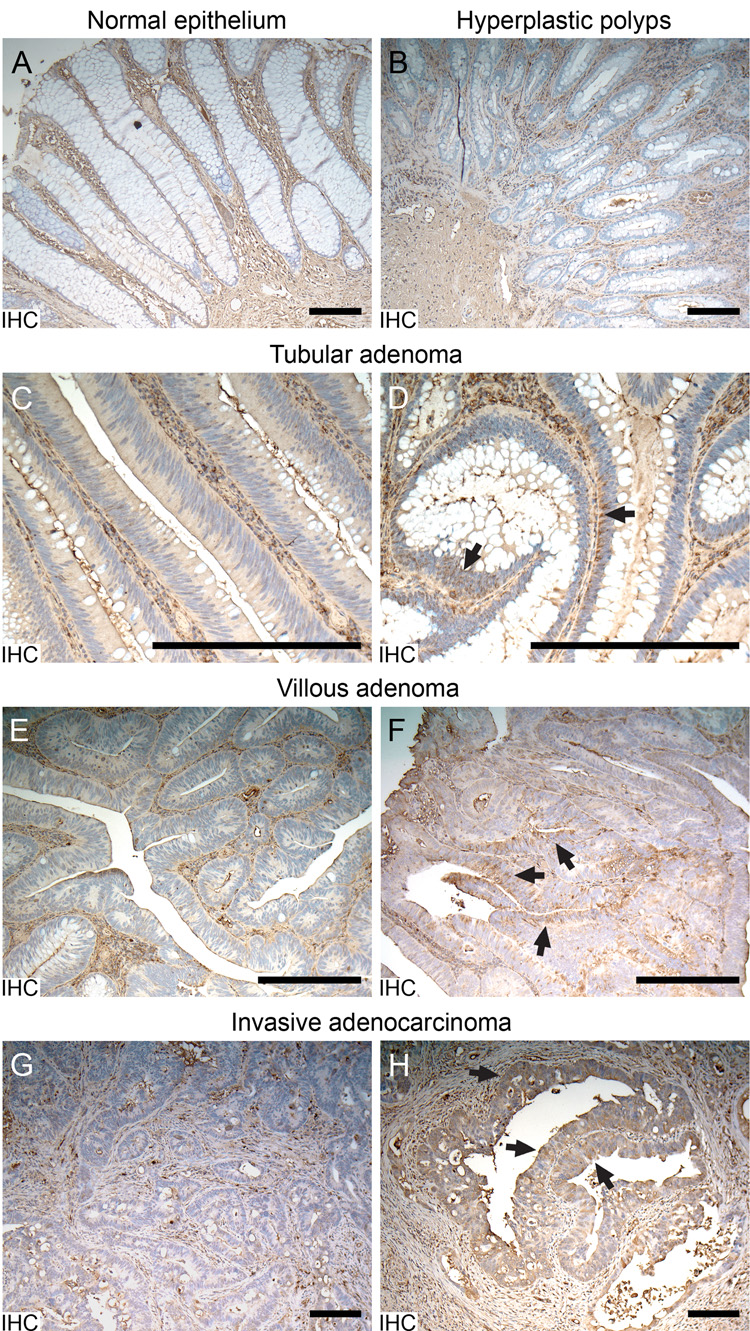

Discrimination between the human colonic adenoma and the hyperplastic polyp by IHC for vimentin

Previous reports of EMT in human colorectal cancers have described this event only in invasive/metastatic adenocarcinomas or in cell lines derived from such adenocarcinomas (Bates et al. 2005; Brabletz et al. 2005). Therefore, we examined early benign human colorectal tumors for vimentin expression using a monoclonal antibody against human vimentin. Hyperplastic polyps are abnormalities in the human colon of unknown neoplastic potential (Bond 2000). Normal human epithelium (n = 3 anonymous sections) and hyperplastic polyps (n = 4 anonymous sections) did not exhibit ectopic production of vimentin (Figure 2A–B), but strong vimentin staining was detected in cells of mesenchymal origin in the same sections (serving as an internal control). Benign human colonic tumors are classified histologically as either tubular or villous adenomas. Although vimentin protein was absent in most neoplastic cells of tubular adenomas (Figure 2C), it was detected in the cytoplasm of a subset of neoplastic cells within this adenoma type (Figure 2D). Villous adenomas, which show high grade dysplasia, are considered more advanced than the tubular lesions. Some such tumors were free of vimentin (Figure 2E), while others showed strong staining (Figure 2F), exhibiting a patchy distribution. As in murine adenomas, a patchy pattern of vimentin expression could be observed in both the peripheral and central regions of human villous adenomas. However, the distribution pattern of vimentin differed between murine and human tumors. In the human adenomas, vimentin was not restricted to the basolateral region of neoplastic cells.

Figure 2. Vimentin production detected by IHC in human colonic tumors.

A. Vimentin signal (brown) detected in mesenchymal cells, but not in the normal human colonic epithelium. B. Lack of detectable vimentin signal in the epithelium of hyperplastic polyps. C. A region of tubular adenoma without epithelial production of vimentin. D. A few tubular adenoma cells showing positive signals of vimentin (arrows). E. A region of villous adenoma without epithelial production of vimentin. F. A region of villous adenoma showing apparent positive signals of vimentin (arrows). G. A region of invasive adenocarcinoma showing production of vimentin only in mesenchymal cells. H. A region of invasive adenocarcinoma showing production of vimentin (arrows) in invading epithelial neoplastic cells. Size bars, 200 µm

Vimentin in the invasive adenocarcinoma of the human colon

Three invasive human adenocarcinomas were included in our study. In these cancers, invasion extended into the submucosa and the muscular layer. Interestingly, vimentin production was not uniform as the tumor invaded into deeper structures. Some invading neoplastic cells gave no detectable vimentin signals (Figure 2G), while others from the same tumor expressed strong signals (Figure 2H arrows). Compared with villous adenomas, the vimentin signals in invading neoplastic cells were more evenly distributed in the cytoplasm, indicating that these cells were less polarized. Stromal cells and other mesenchymal cells in human sections served as positive controls, showing strong uniform vimentin staining.

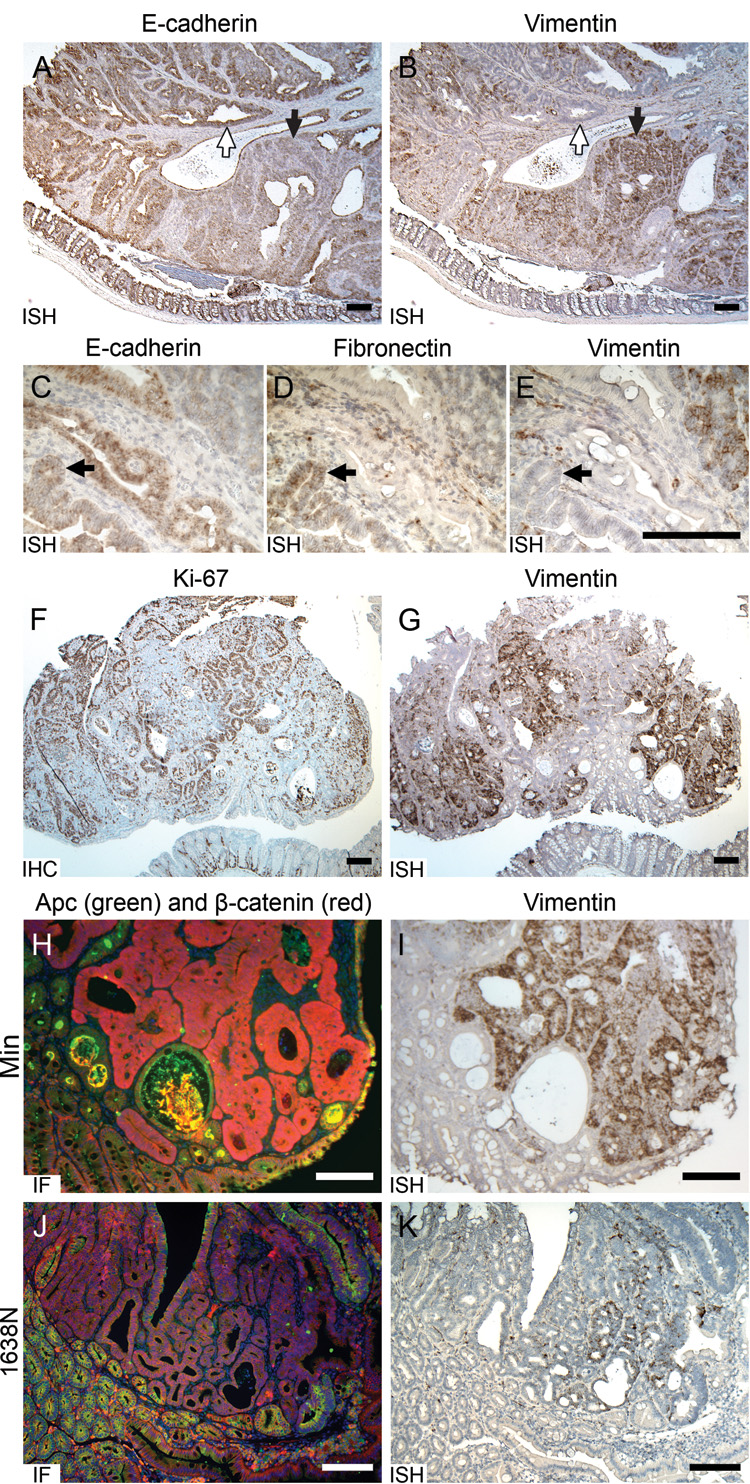

The EMT core: vimentin and fibronectin expression and E-cadherin extinction

Expression of vimentin, a classical mesenchymal marker, in neoplastic cells derived from the colonic epithelium suggests that these cells are initiating the molecular program associated with EMT. One of the hallmarks of EMT is loss of the epithelial marker, E-cadherin. ISH showed that E-cadherin RNA is present in most neoplastic cells as well as in normal intestinal epithelium (Figure 3A). However, the expression level varied greatly in different regions of colonic tumors. Vimentin and E-cadherin RNA staining in adjacent sections of Min colonic tumors revealed reciprocal expression patterns (Figure 3A–B): E-cadherin was much lower in regions where vimentin was strongly expressed (Figure 3A–B black arrows), while vimentin was barely detectable in most regions maintaining strong E-cadherin expression (Figure 3A–B white-filled arrows). This reciprocal pattern was observed in all tumors examined (n = 7), although rare neoplastic cells maintained moderate expression of both genes. These results further support the suggestion that some neoplastic cells of early intestinal adenomas in Min mice are initiating EMT.

Figure 3. Molecular and cellular phenotypes associated with vimentin expression in B6 intestinal tumors.

A. E-cadherin and (B) vimentin demonstrated reciprocal RNA expression pattern in a Min colonic adenoma. White-filled arrows, the region with strong E-cadherin and weak vimentin expression. Black arrows, the region carrying reduced E-cadherin and elevated vimentin expression. C. Comparison of fibronectin RNA expression with (D) E-cadherin and (E) vimentin in Min colonic adenomas. Black arrows, a region carrying elevated fibronectin expression, moderate E-cadherin expression and weak vimentin expression. F. Comparison of Ki-67 by IHC with (G) vimentin expression by ISH in a Min colonic adenoma. H. A Min adenoma with immunofluorescent (IF) staining of wild-type APC (green) and β-catenin (red), and (I) an adjacent section stained by ISH for vimentin RNA (brown). J. An adenoma induced by 1638N mutation stained by IF with wild-type APC (green) and β-catenin (red), and (K) an adjacent section stained by ISH for vimentin RNA (brown). Size bars, 200 µm.

Fibronectin is an extracellular adhesion molecule, serving as an anchor to connect cells with the extracellular matrix (Wierzbicka-Patynowski and Schwarzbauer 2003). This protein is often used as a mesenchymal marker, since it is usually expressed in cells of mesenchymal origin (Limper and Roman 1992) as well as in some types of epithelial neoplastic cells undergoing EMT (Maschler et al. 2005). To investigate whether fibronectin is expressed in murine colonic neoplastic cells, ISH was performed with fibronectin-specific probes. Some epithelial-like neoplastic cells demonstrated weak to moderate expression (Figure 3D), although most neoplastic cells, as well as normal epithelial cells adjacent to the tumor, were fibronectin-free. We compared the expression of fibronectin with adjacent sections stained for vimentin and E-cadherin. To our surprise, the regions showing fibronectin expression were different from those staining strongly for vimentin. Instead, fibronectin-positive regions showed reduced but moderate expression of E-cadherin and weak expression of vimentin (Figure 3C–E, arrows). The stromal cells and other mesenchymal cells within the tumor sections were used as internal positive controls, and, as expected, expressed both fibronectin and vimentin.

Truncation of the EMT system in adenomas: Lack of Snail expression

Snail is a zinc-finger transcription factor. It suppresses expression of E-cadherin, contributing to the initiation of classical EMT (Cano et al. 2000). To determine whether Snail is involved in the reduction of E-cadherin and elevation of vimentin that we have observed in adenomas, ISH and IHC were performed on the Min colonic tumor sections. Both approaches detected weak signals, localized mainly in normal mesenchymal cells (data not shown). A mouse blastocyst section, used as positive control for the Snail antibody (Franci et al. 2006) in the same experiment, demonstrated strong staining of Snail in the extra-embryonic cells (data not shown). Since Snail is not expressed in the tumor cells that show a reduction of E-cadherin and an increase of vimentin levels, we concluded that the elements of EMT that we have observed in adenomas are not associated with Snail. We have also examined by ISH and IHC other known E-cadherin suppressors/EMT inducers, including slug (Nieto et al. 1994), Smad interacting protein 1 (SIP1) (Comijn et al. 2001), twist (Yang et al. 2004), and integrin-like kinase (ILK) (Li et al. 2003). None of these molecules demonstrated a clear association with E-cadherin reduction within colonic tumors, indicating that E-cadherin in Min colonic adenomas is suppressed by a suppressor distinct from the regulator of canonical EMT. We characterize our observations of expression of some but not all of the canonical features of EMT as “truncated EMT”.

Cell proliferation and signaling associated with truncated EMT

To investigate the relationship of cell proliferation to the cells showing vimentin expression in Min colonic tumors, we used IHC to detect Ki67, a marker for proliferating cells. As expected, many cells both in tumors and in the proliferation zones near the bottom of normal crypts demonstrated strong Ki67 staining (Figure 3F). Consistent with previous reports on the EMT (Brabletz et al. 2001), our results comparing Ki67 and vimentin on adjacent sections revealed a mutually exclusive pattern of expression of these two markers: regions with strong vimentin expression showed a relatively low density of proliferating cells, while those with a high density of proliferating cells contained little vimentin (5/5 tumors; Figure 3F–G).

Intensity of Wnt signaling and vimentin expression in intestinal tumors induced by two different Apc mutations

Loss of wild-type Apc function in intestinal neoplastic cells of Min mice constitutively activates the Wnt signaling pathway and results in accumulation of cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin (Behrens et al. 1998; Chen et al. 2003). Dual-immunofluorescent staining for β-catenin and Apc protein was performed on sections of Min tumors. In the normal intestinal epithelium maintaining wild-type Apc, β-catenin was detected along cell membranes. By contrast, in neoplastic cells, where Apc was inactive, β-catenin accumulated throughout the cell, including both cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure 3H). Comparison with ISH for vimentin RNA on an adjacent section showed that neoplastic cells expressing EMT markers all lay in regions that showed loss of Apc protein and strong cytoplasmic/nuclear staining of β-catenin (Figure 3H–I). However, some neoplastic cells with strong cytoplasmic β-catenin staining were vimentin-negative. A previous study of cultured breast cancer cells has shown that vimentin can be directly transactivated by the accumulation and translocation of cytoplasmic β-catenin (Gilles et al. 2003). Our study, by contrast, focuses on the early intestinal adenoma, in vivo.

A second genetic mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis carries the Apc1638N insertion allele (1638N) (Fodde et al. 1994). Compared to Min mice, carriers of this mutation develop substantially fewer tumors in the small intestine (Fodde et al. 1994). Tumors in congenic B6-1638N mice appear to acquire only low levels of Wnt-signaling, unlike the strong signaling of Min mice. Immunofluorescent staining of tumors for both Apc and β-catenin revealed cells in which wild-type Apc was absent, yet, unlike Min tumors, cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin staining in these tumors was very weak (Figure 3J). ISH detected positive vimentin signals within neoplastic cells in only two out of ten 1638N tumors (20%, compared to 79% in Min tumors from the small intestine, p < 0.01). Further, the spatial distribution of vimentin signals (Figure 3K) was relatively narrow in these tumors compared to Min, while control vimentin signals could be detected in stromal cells of all tumors. Finally, a comparison of staining for vimentin RNA and Apc/ β-catenin on adjacent sections demonstrated that the vimentin-expressing cells in 1638N tumors were located within the tumor regions as defined by the absence of wild-type Apc (Figure 3J–K). Thus, ectopic expression of vimentin is positively associated with aberrant Wnt signaling within intestinal adenomas.

Dependence of vimentin expression on the TGF-β signaling pathway

The TGF-β signaling pathway plays an important role in intestinal tumorigenesis (Bachman and Park 2005). This pathway appears to work through the phosphorylation of Smad-family transducers (Kaklamani and Pasche 2004). Thus, pSmad2 protein provides a marker for active TGF-β signaling (Heldin et al. 1997). Immunostaining of Min colonic tumors demonstrated strong positive pSmad2 signals in most nuclei of neoplastic cells as well as in normal epithelia (data not shown), including the neoplastic cells showing strong vimentin expression. Therefore, neoplastic cells expressing vimentin maintain active TGF-β signaling.

We investigated further whether vimentin expression was dependent upon TGF-β signaling by examining Smad3-deficient mice which develop spontaneous tumors of the cecum and colon (Zhu et al. 1998), but not the small intestine. Smad3 is one of the important intracellular effectors in the TGF-β signaling pathway (Roberts et al. 2003). Immunohistochemistry to detect vimentin antigen in these tumors revealed no such protein in neoplastic cells of 7 cecal and 6 colonic tumors induced by Smad3 (data not shown). We next investigated whether Min-induced tumors from the small intestine of Smad3-deficient Min mice expressed vimentin. Compared with the Min-induced tumors on the same 129 background but wild-type for Smad3 (Figure 4A–B), the Smad3-deficient Min tumors showed a significantly lower frequency of expression (13% vs. 82% of tumors, p < 0.01) and much smaller regions of vimentin production. These results suggest that the strong vimentin signals we observed in Min tumors are at least partially dependent on TGF-β signaling via Smad3. The rare but finite cases of vimentin positivity (1 out of 8 Smad3-deficient Min tumors) can perhaps be explained by a functional redundancy in the Smad family.

Dependence of vimentin expression on the Ras signaling pathway

Activated Ras signaling has been reported to be a key condition for EMT initiation in most in vitro studies (Janda et al. 2002; Gotzmann et al. 2004). To investigate the Ras signaling pathway, immunohistochemistry was performed with a monoclonal antibody against phosphorylated-p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (pMAPK), a marker for active Ras signaling (Marais and Marshall 1996). The Min tumors demonstrated positive pMAPK staining in some regions (Figure 4C). Surprisingly, staining of pMAPK in these colonic tumors did not correlate with vimentin expression (Figure 4D). Instead, positive pMAPK staining is correlated in general with a low expression of vimentin (Figure 4C–D, black arrows), and strong vimentin expression was correlated in general with weak pMAPK staining (Figure 4C–D, white-filled arrows). This in vivo result indicates that although Ras signaling may be needed to induce vimentin expression, persistent signaling through MAPK phosphorylation is not required for vimentin expression.

DISCUSSION

As summarized in Table 1, we have observed strongly elevated expression of vimentin, a traditional mesenchymal marker, during the earliest stage of tumorigenesis in three different mouse models of human intestinal cancer. Similar observations in spontaneous benign human colonic adenomas indicate that our observations in the mouse may also be relevant to the human disease. Along with elevated vimentin expression, we have also observed several molecular events in neoplastic cells commonly associated with cancer-associated EMT, including loss of the epithelial marker E-cadherin, increase of the mesenchymal marker fibronectin, decrease of proliferation, and strong associations of vimentin expression with Wnt and TGF-β signaling.

Only a subset of the neoplastic cells in the three invasive human colonic adenocarcinomas we have tested demonstrated production of vimentin. Thus, perhaps vimentin expression is elevated only at early stages of tumorigenesis before the gene is silenced by hypermethylation. Indeed, hypermethylation and possible silencing of the vimentin gene have been detected in colonic cancer cells within stool samples of some adenocarcinoma patients (Chen et al. 2005). Further investigation is needed to clarify whether the vimentin gene is hypermethylated in the human adenocarcinoma cells lacking vimentin expression.

The mesenchymal features gained in EMT, such as enhanced motility, facilitate tumor invasion and metastasis. Therefore, this process is generally assumed to be an event associated with the late stages of tumorigenesis (Gotzmann et al. 2004; Bates and Mercurio 2005). In fact, cells undergoing EMT in human cancers have usually been found on the invasion front of a malignant tumor (Gotzmann et al. 2004). What is the functional significance of these molecular EMT signatures for neoplastic cells of early Min-induced dysplastic epithelial adenomas which lack signs of invasion and metastasis (Figure 1A, 2C–F)? Truncated EMT may be important in tissue remodeling.

Rapid proliferation leads to dramatic morphological changes of the intestinal epithelium during adenomagenesis, including loss of the cellular monolayer. Consequently, such cells lose their polarity and intercellular tight junctions. Although adenomas have not acquired the morphological features of mesenchyme, some have started to lose their epithelial features, as in the initial steps of EMT. Thus, the molecular alterations we have observed may cause or reflect the morphological changes involved in dysplasia, but not in the hyperplastic polyp. Yet, the end result of typical EMT – tumor cells with mesenchymal morphology and nuclear translocation of β-catenin – are absent in mouse and human intestinal adenomas. Accordingly, we hypothesize that the adenoma cells expressing elevated vimentin are undergoing truncated EMT, which would promote tissue remodeling, but would not necessarily lead to complete EMT.

Tissue remodeling occurs continuously during tumorigenesis (Herzig and Christofori 2002). Some genes whose functions in neoplasia were initially thought to be associated with metastasis may also play an important role in tissue remodeling at the dysplastic adenoma stage. One such example is matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7), which had been expected to be involved in tumor invasion. Instead, loss of this metalloproteinase in an Mmp7 knockout allele strongly reduces the multiplicity of Min intestinal adenomas (Wilson et al. 1997). Boudreau and colleagues (2007) have suggested that the loss of tight junctional communication in the epithelium, owing to a deficiency in cathepsin L, accounts for a major increase in the multiplicity of Min adenomas. Thus, the core molecular alterations traditionally associated with EMT may also act to increase the plasticity of early tumors and facilitate their dysplastic expansion from the epithelial sheet.

Other observations in adenomas, besides the expression of vimentin and loss of E-cadherin, reinforce the resemblance to EMT. The Wnt pathway is involved in both developmental(Kemler et al. 2004) and invasive EMT (Taki et al. 2003; Brabletz et al. 2005). We observed a positive association of vimentin expression with activated Wnt signaling, consistent with recent reports of a strong association between EMT and Wnt-signaling (Eger et al. 2000). Members of the TGF-β family can induce and maintain EMT through Smad-dependent pathways in several models (Zavadil and Bottinger 2005). Thus, our results are also consistent with a positive effect of the TGF-β signaling pathway on EMT (Janda et al. 2002). Further, we observed a negative correlation between cell proliferation and vimentin expression, consistent with previous reports on EMT (Brabletz et al. 2001).

Certain of our observations, however, are inconsistent with canonical EMT. For example, Ras signaling, critical for complete EMT (Janda et al. 2002; Gotzmann et al. 2004), is silenced in the neoplastic cells expressing vimentin (Figure 4C–D). Further, expression of fibronectin, another mesenchymal marker normally associated with EMT (Yang et al. 2004), did not show a consistent correlation with expression of vimentin. Finally, Snail and several other canonical E-cadherin suppressors/EMT inducers did not demonstrate association with reduction of E-cadherin and increase of vimentin in murine colonic adenomas. Perhaps these exceptions mark the difference between full EMT involved in metastasis and truncated EMT involved only in tissue remodeling.

This truncated EMT hypothesis can be actively addressed in mouse models by combining array analysis with constitutive or conditional inactivation of genes of interest. In particular, a cluster analysis of genes whose expression in adenomas mirrors those of vimentin and E-cadherin may lead to the identification of molecules that participate in the hypothesized dysplastic remodeling process.

Recent reports indicated that the tendency of tumors to metastasize may be predetermined by molecular changes during early tumorigenesis (van de Vijver et al. 2002) or by host polymorphisms (Hunter 2005). A possible relationship between truncated EMT and metastasis could be investigated given a mouse model with predictable invasive and metastatic colon cancer. Progress toward obtaining such a model of invasive tumors may exist in Min mice deficient in the ephrin receptor (Batlle et al. 2005). Further, transgenesis for genes required for typical EMT, such as activated Ras, Snail and integrin-like kinase, may contribute to EMT and the invasion/metastasis potential of mouse models. In such animals, conditional overexpression or ablation of related genes, including vimentin, fibronectin, and E-cadherin could be used to test their individual effects in the causation of the EMT.

In the present report, we have succeeded in using cellular markers to identify molecular alterations associated with EMT in neoplastic cells of epithelial origin. This extensive study provides an important initial insight into the cell biology of early stages in tumorigenesis. The power of contemporary mouse genetics can now be brought to bear to evaluate the mechanisms and importance of truncated EMT.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank our colleagues in the Mouse Models for Human Cancer Consortium for the microarray analysis that has provided the starting point for this investigation. We thank Ismo Virtanen for providing the antibody to Snail. David Threadgill has generously provided sections of appropriately fixed AOM tumors for our ISH analysis. Jose Torrealba has generously provided sections of human colonic lesions. The Histotechnology Facility of the McArdle Laboratory (Jane Weeks, leader) has provided sections of high quality for this study. Cheri Pasch and Kathy Helmuth have provided fastidious assistance in ISH and Dawn Albrecht in the maintenance of pedigreed mouse kindreds and Alexandra Shedlovsky for BTBR Min tumors. Linda Clipson has provided both skilled assistance in organizing the manuscript but also, in conjunction with Alexandra Shedlovsky, detailed critique. Finally, we thank other members of the Dove laboratory for helpful discussion. Our research was supported by grants R37-CA63677 and U01-CA84227 from the NCI to WFD. This is publication #3638 from the Laboratory of Genetics, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Abbreviations

- 1638N

Apc1638N insertion allele

- 129

129S6/SvEvTac

- AOM

azoxymethane

- BTBR

BTBR/Pas

- B6

C57BL/6J

- BR

C57BR/cdcJ

- DAB

3,3′-Diaminobenzidine

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- IF

immunofluorescence

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- ISH

in situ hybridization

- Min

ApcMin/+

- MMP7

matrix metalloproteinase 7

- pMAPK

phosphorylated-p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase

- pSmad2

phosphorylated Smad2

REFERENCES

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2007. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Amos-Landgraf JM, Kwong LN, Kendziorski CM, Reichelderfer M, Torrealba J, Weichert J, Haag JD, Chen KS, Waller JL, Gould MN, Dove WF. A target-selected Apc-mutant rat kindred enhances the modeling of familial human colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4036–4041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611690104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman KE, Park BH. Duel nature of TGF-β signaling: tumor suppressor vs. tumor promoter. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17:49–54. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000143682.45316.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates RC, Bellovin DI, Brown C, Maynard E, Wu B, Kawakatsu H, Sheppard D, Oettgen P, Mercurio AM. Transcriptional activation of integrin β6 during the epithelial-mesenchymal transition defines a novel prognostic indicator of aggressive colon carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:339–347. doi: 10.1172/JCI23183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates RC, Mercurio AM. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and colorectal cancer progression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:365–370. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.4.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batlle E, Bacani J, Begthel H, Jonkeer S, Gregorieff A, van de BM, Malats N, Sancho E, Boon E, Pawson T, Gallinger S, Pals S, Clevers H. EphB receptor activity suppresses colorectal cancer progression. Nature. 2005;435:1126–1130. doi: 10.1038/nature03626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J, Jerchow BA, Wurtele M, Grimm J, Asbrand C, Wirtz R, Kuhl M, Wedlich D, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of an axin homolog, conductin, with β-catenin, APC, and GSK3β. Science. 1998;280:596–599. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond JH. Polyp guideline: diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance for patients with colorectal polyps. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3053–3063. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau F, Lussier CR, Mongrain S, Darsigny M, Drouin JL, Doyon G, Suh ER, Beaulieu JF, Rivard N, Perreault N. Loss of cathepsin L activity promotes claudin-1 overexpression and intestinal neoplasia. FASEB J. 2007;21:3853–3865. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8113com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabletz T, Hlubek F, Spaderna S, Schmalhofer O, Hiendlmeyer E, Jung A, Kirchner T. Invasion and metastasis in colorectal cancer: epithelial-mesenchymal transition, mesenchymal-epithelial transition, stem cells and β-catenin. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;179:56–65. doi: 10.1159/000084509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabletz T, Jung A, Reu S, Porzner M, Hlubek F, Kunz-Schughart LA, Knuechel R, Kirchner T. Variable β-catenin expression in colorectal cancers indicates tumor progression driven by the tumor environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10356–10361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171610498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WD, Han ZJ, Skoletsky J, Olson J, Sah J, Myeroff L, Platzer P, Lu S, Dawson D, Willis J, Pretlow TP, Lutterbaugh J, Kasturi L, Willson JK, Rao JS, Shuber A, Markowitz SD. Detection in fecal DNA of colon cancer-specific methylation of the nonexpressed vimentin gene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1124–1132. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Halberg RB, Ehrhardt WM, Torrealba J, Dove WF. Clusterin as a biomarker in murine and human intestinal neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9530–9535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1233633100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen JJ, Rajasekaran AK. Reassessing epithelial to mesenchymal transition as a prerequisite for carcinoma invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8319–8326. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comijn J, Berx G, Vermassen P, Verschueren K, van Grunsven L, Bruyneel E, Mareel M, Huylebroeck D, van Roy F. The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eger A, Stockinger A, Schaffhauser B, Beug H, Foisner R. Epithelial mesenchymal transition by c-Fos estrogen receptor activation involves nuclear translocation of β-catenin and upregulation of β-catenin/lymphoid enhancer binding factor-1 transcriptional activity. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:173–188. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodde R, Edelmann W, Yang K, van Leeuwen C, Carlson C, Renault B, Breukel C, Alt E, Lipkin M, Khan PM, Kucherlapati R. A targeted chain-termination mutation in the mouse Apc gene results in multiple intestinal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8969–8973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franci C, Takkunen M, Dave N, Alameda F, Gomez S, Rodriguez R, Escriva M, Montserrat-Sentis B, Baro T, Garrido M, Bonilla F, Virtanen I, Garcia dH. Expression of Snail protein in tumor-stroma interface. Oncogene. 2006;25:5134–5144. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles C, Polette M, Mestdagt M, Nawrocki-Raby B, Ruggeri P, Birembaut P, Foidart JM. Transactivation of vimentin by beta-catenin in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2003;63:2658–2664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotzmann J, Mikula M, Eger A, Schulte-Hermann R, Foisner R, Beug H, Mikulits W. Molecular aspects of epithelial cell plasticity: implications for local tumor invasion and metastasis. Mutat Res. 2004;566:9–20. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(03)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenburg G, Hay ED. Epithelia suspended in collagen gels can lose polarity and express characteristics of migrating mesenchymal cells. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:333–339. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-β signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390:465–471. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig M, Christofori G. Recent advances in cancer research: mouse models of tumorigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1602:97–113. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter K. The intersection of inheritance and metastasis: the role and implications of germline polymorphism in tumor dissemination. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1719–1721. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.12.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda E, Lehmann K, Killisch I, Jechlinger M, Herzig M, Downward J, Beug H, Grunert S. Ras and TGFβ cooperatively regulate epithelial cell plasticity and metastasis: dissection of Ras signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser S, Park YK, Franklin JL, Halberg RB, Yu M, Jessen WJ, Freudenberg J, Chen X, Haigis K, Jegga AG, Kong S, Sakthivel B, Xu H, Reichling T, Azhar M, Boivin GP, Roberts RB, Bissahoyo AC, Gonzales F, Bloom GC, Eschrich S, Carter SL, Aronow JE, Kleimeyer J, Kleimeyer M, Ramaswamy V, Settle SH, Boone B, Levy S, Graff JM, Doetschman T, Groden J, Dove WF, Threadgill DW, Yeatman TJ, Coffey RJ, Jr, Aronow BJ. Transcriptional recapitulation and subversion of embryonic colon development by mouse colon tumor models and human colon cancer. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R131. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaklamani VG, Pasche B. Role of TGF-β in cancer and the potential for therapy and prevention. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2004;4:649–661. doi: 10.1586/14737140.4.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Massague J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: twist in development and metastasis. Cell. 2004;118:277–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemler R, Hierholzer A, Kanzler B, Kuppig S, Hansen K, Taketo MM, de Vries WN, Knowles BB, Solter D. Stabilization of β-catenin in the mouse zygote leads to premature epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the epiblast. Development. 2004;131:5817–5824. doi: 10.1242/dev.01458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong LN, Shedlovsky A, Biehl BS, Clipson L, Pasch CA, Dove WF. Identification of Mom7, a novel modifier of ApcMin/+ on mouse Chromosome 18. Genetics. 2007;176:1237–1244. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.071217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yang J, Dai C, Wu C, Liu Y. Role for integrin-linked kinase in mediating tubular epithelial to mesenchymal transition and renal interstitial fibrogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:503–516. doi: 10.1172/JCI17913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limper AH, Roman J. Fibronectin. A versatile matrix protein with roles in thoracic development, repair and infection. Chest. 1992;101:1663–1673. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marais R, Marshall CJ. Control of the ERK MAP kinase cascade by Ras and Raf. Cancer Surv. 1996;27:101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschler S, Wirl G, Spring H, Bredow DV, Sordat I, Beug H, Reichmann E. Tumor cell invasiveness correlates with changes in integrin expression and localization. Oncogene. 2005;24:2032–2041. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke A, Philippi C, Vogelmann R, Seidel B, Lutz MP, Adler G, Wedlich D. Down-regulation of E-cadherin gene expression by collagen type I and type III in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3508–3517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser AR, Pitot HC, Dove WF. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247:322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngai J, Capetanaki YG, Lazarides E. Expression of the genes coding for the intermediate filament proteins vimentin and desmin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;455:144–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb50409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto MA, Sargent MG, Wilkinson DG, Cooke J. Control of cell behavior during vertebrate development by Slug, a zinc finger gene. Science. 1994;264:835–839. doi: 10.1126/science.7513443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BJ, Park JI, Byun DS, Park JH, Chi SG. Mitogenic conversion of transforming growth factor-β1 effect by oncogenic Ha-Ras-induced activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3031–3038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R, Edberg DD, Li Y. Architectural transcription factor HMGI(Y) promotes tumor progression and mesenchymal transition of human epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:575–594. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.575-594.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AB, Russo A, Felici A, Flanders KC. Smad3: a key player in pathogenetic mechanisms dependent on TGF-β. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;995:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savagner P. Leaving the neighborhood: molecular mechanisms involved during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Bioessays. 2001;23:912–923. doi: 10.1002/bies.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, von Eschenbach AC, Wender R, Levin B, Byers T, Rothenberger D, Brooks D, Creasman W, Cohen C, Runowicz C, Saslow D, Cokkinides V, Eyre H. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. Also: update 2001--testing for early lung cancer detection. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:38–75. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn MB. The war on cancer. Lancet. 1996;347:1377–1381. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Preisinger AC, Moser AR, Luongo C, Gould KA, Dove WF. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Wakabayashi K. Gene mutations and altered gene expression in azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in rodents. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:475–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taki M, Kamata N, Yokoyama K, Fujimoto R, Tsutsumi S, Nagayama M. Down-regulation of Wnt-4 and up-regulation of Wnt-5a expression by epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human squamous carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:593–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarin D, Thompson EW, Newgreen DF. The fallacy of epithelial mesenchymal transition in neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5996–6000. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van't Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AA, Voskuil DW, Schreiber GJ, Peterse JL, Roberts C, Marton MJ, Parrish M, Atsma D, Witteveen A, Glas A, Delahaye L, van d V, Bartelink H, Rodenhuis S, Rutgers ET, Friend SH, Bernards R. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka-Patynowski I, Schwarzbauer JE. The ins and outs of fibronectin matrix assembly. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3269–3276. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CL, Heppner KJ, Labosky PA, Hogan BLM, Matrisian LM. Intestinal tumorigenesis is suppressed in mice lacking the metalloproteinase matrilysin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1402–1407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjoblom T, Leary RJ, Shen D, Boca SM, Barber T, Ptak J, Silliman N, Szabo S, Dezso Z, Ustyanksky V, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Karchin R, Wilson PA, Kaminker JS, Zhang Z, Croshaw R, Willis J, Dawson D, Shipitsin M, Willson JK, Sukumar S, Polyak K, Park BH, Pethiyagoda CL, Pant PV, Ballinger DG, Sparks AB, Hartigan J, Smith DR, Suh E, Papadopoulos N, Buckhaults P, Markowitz SD, Parmigiani G, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE, Vogelstein B. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavadil J, Bottinger EP. TGF-β and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. Oncogene. 2005;24:5764–5774. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Richardson JA, Parada LF, Graff JM. Smad3 mutant mice develop metastatic colorectal cancer. Cell. 1998;94:703–714. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]