Abstract

The discovery that botanical cannabinoids such as delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol exert some of their effect through binding specific cannabinoid receptor sites has led to the discovery of an endocannabinoid signaling system, which in turn has spurred research into the mechanisms of action and addiction potential of cannabis on the one hand, while opening the possibility of developing novel therapeutic agents on the other. This paper reviews current understanding of CB1, CB2, and other possible cannabinoid receptors, their arachidonic acid derived ligands (e.g. anandamide; 2 arachidonoyl glycerol), and their possible physiological roles. CB1 is heavily represented in the central nervous system, but is found in other tissues as well; CB2 tends to be localized to immune cells. Activation of the endocannabinoid system can result in enhanced or dampened activity in various neural circuits depending on their own state of activation. This suggests that one function of the endocannabinoid system may be to maintain steady state. The therapeutic action of botanical cannabis or of synthetic molecules that are agonists, antagonists, or which may otherwise modify endocannabinoid metabolism and activity indicates they may have promise as neuroprotectants, and may be of value in the treatment of certain types of pain, epilepsy, spasticity, eating disorders, inflammation, and possibly blood pressure control.

Keywords: Cannabis, Endocannabinoid system, Therapeutics, Dependence

Throughout much of the twentieth century discourse on marijuana was framed principally in sociopolitical terms throughout much of the world, and most especially in the US. The official, governmental point of view in the US, Canada, and Western Europe was that marijuana was an addicting drug devoid of therapeutic benefits. Hence, it was classified as a ‘Schedule 1’ agent, i.e. a dangerous drug of no medical value.

An opposing view, which gradually gained currency from the 1960 s onward, was that marijuana was a relatively harmless naturally occurring substance. Most users experienced marijuana as having calming, perhaps soporific effects, causing transient memory and other cognitive impairment, and stimulating appetite. While occasional untoward effects were acknowledged (e.g. anxiety reactions; psychotic phenomena), the general view was that any alterations in mood and cognition were transient and that marijuana had little or no addiction potential, at least as evidenced by apparent lack of physiological withdrawal symptoms on its discontinuation.

Gaoni and Mechoulam’s [1] characterization of some of marijuana’s cannabinoid constituents, and in particular, the identification of delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) as the prime psychoactive drug, stimulated laboratory, animal model, and human research; however, whereas, some of the animal studies probed various physiological properties of the cannabinoids, including some that might have therapeutic values, human studies generally concentrated on the addictive and adverse affects of THC and marijuana. As a result, by the last decade of the twentieth century it remained an open question whether the cannabinoids could have any therapeutic value whatever.

1. Discovery of the endocannabinoid system

A major paradigmatic shift occurred with the discovery [2] and cloning [3,4] of delta-9 THC binding sites. The first discovered cannabinoid receptor was termed CB1. Subsequently, a second receptor, termed CB2 was characterized [5]. Thereafter, anandamide and 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG), derivatives of arachidonic acid, were identified as endogenous ligands to CB1 and CB2 [6–8].

The CB1 receptor is heavily concentrated in the central nervous system, but is found in other tissues as well, including liver, gut, uterus, prostate, adrenals, and the cardiovascular system. CB2 tends to be localized to cells of immune origin. In the brain the CB1 receptors tend to be concentrated in sub cortical structures including cerebellum, basal ganglia, and other limbic lobe circuitries, as well as in the hippocampus. Though less concentrated, CB1 receptors are also found in other parts of the cortex. As noted above, other tissues are also populated by CB1, and in particular, these include the pituitary, adrenal, GI tract, urinary bladder, and heart and blood vessels. Of the botanically derived cannabinoids, delta-9 THC, which is the most potent psychoactively, binds to both CB1 and CB2 receptors. Delta-8 THC also binds to both, though somewhat less strongly. Cannabidiol binds to none of the receptors, is devoid of psychoactive effect, yet may have some anti-inflammatory and smooth muscle contraction inhibitory actions mediated either by a yet uncharacterized CB receptor or another mechanism entirely.

2. Structure and function of CB receptors

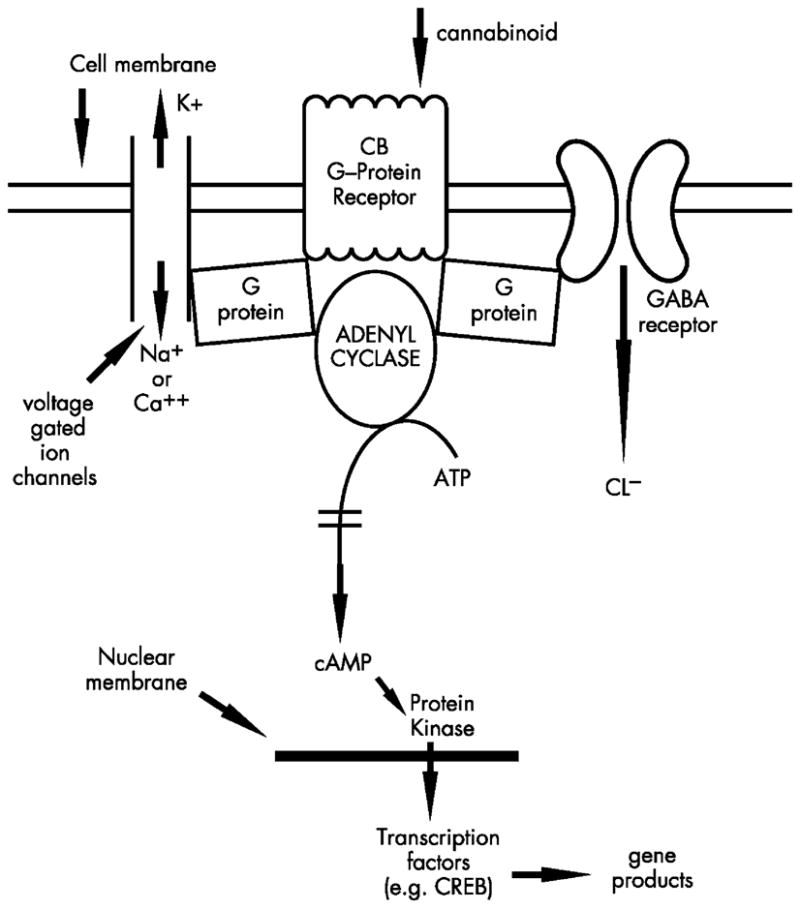

The CB receptors are part of the super family of G-protein coupled receptors. Common features of such receptors are that they consist of a protein with seven transmembrane regions that can couple to stimulatory or inhibitory intracellular G-proteins. Such G-proteins can then up or down regulate enzymes such as adenyl cyclase which can then increase or decrease cyclic AMP (c-AMP) production. c-AMP in turn can activate protein kinase to phosphorylate transcription factors such as cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB), which can in turn activate gene expression through production of various messenger RNAs. In the case of activation of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor, the typical action is actually inhibitory, that is reduction of c-AMP formation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of CB receptor

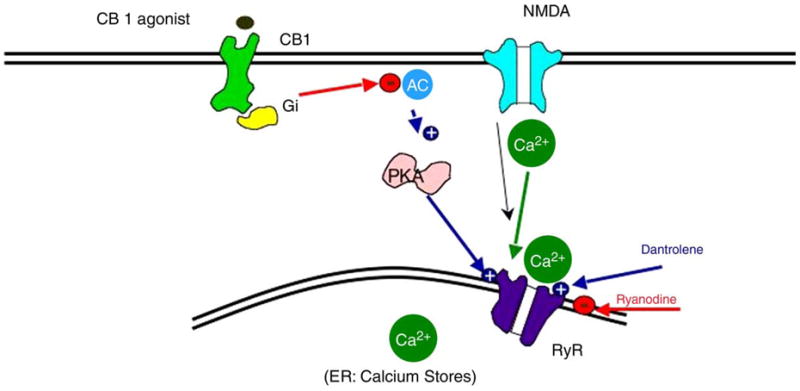

Such down regulation of c-AMP is one possible explanation for the putative neuroprotective actions of CB1 agonists. Neurons can be injured by activation of NMDA receptors that permit entry of calcium, which in turn can activate calcium channel receptors (ryanodine receptors) intracellularly on the endoplasmic reticulum. Ryanodine receptors, when activated by calcium can cause further release of calcium into the cytoplasm producing a toxic cascade. CB1 agonists may act through two mechanisms to ‘protect’ the neuron; first, through a G-protein coupled mechanism they may reduce NMDA-controlled calcium influx; second, since protein kinase A (PKA) can stimulate the ryanodine receptor, CB1 agonists, by reducing PKA may effectively reduce efflux of calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 2) [9].

Fig. 2.

Possible mechanism of CB 1 agonist neuroprotection Modified from Zhuang.et.Al.J Neuropharmacology.2005;48:1086–1096

Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are located at many of the sites associated with peripheral and central processing of nociceptive messages including medium and large-sized cells of rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [10] and spinal interneurons [11]. Immunostaining studies report strong coexpression of CB1 receptors and vanilloid VR1 receptors in adult rat DRG neurons, which is of particular interest given that anandamide is an agonist both at inhibitory cannabinoid receptors and at pronociceptive VR1 receptors [12]. The antinociceptive activity of cannabinoids is mediated through both central and peripheral mechanisms, as antinociceptive effects of cannabinoids have been widely reported following peripheral, spinal and intracerebroventricular administration of different classes of cannabinoid receptor agonists [13]. While the CB1 receptor has been most commonly thought of as the important receptor in antinociceptive actions of cannabinoids, recent evidence also suggests the peripheral CB2 receptor agonism can elicit anti-nociceptive effects [14], and there may be other, as yet unidentified CB receptor or non-receptor based mechanisms.

The CB1 receptor has also been implicated as essential in the development of the feeding response in mice pup neonates—in the absence of CB1 receptor signaling, mediated either by CB1 antagonism or genetic CB1 deletion, mice pups do not draw milk from the mother and die [15,16]. These data suggest that endocannabinoids play a critical role in survival of the newborn mouse by controlling milk ingestion. Combined with the finding that the level of 2-AG in rodent pup brains peaks immediately after birth [17], it has been suggested that the clinical application of cannabinoids in treating infant failure to thrive deserves investigation as well [15].

CB1 receptors are expressed at high levels in brain regions such as the amygdala, which are implicated in the control of anxiety and fear [18–20]. Pharmacological [21,22] or genetic [23,24] disruption of CB1 receptor activity elicits anxiety-like behaviors in rodents, suggestive of the existence of an intrinsic anxiolytic tone mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. Further, mice lacking CB1 receptors show strongly impaired extinction but unaffected acquisition and consolidation of aversive memories. These effects are associated with elevated levels of endocannabinoids in the basolateral amygdala [25], and suggest that endocannabinoids are crucial for the extinction of aversive memories.

CB1 receptors have been detected on enteric nerves, and pharmacological effects of their activation include gastro-protection, reduction of gastric and intestinal motility and reduction of intestinal secretion [26]. The digestive tract also contains endogenous cannabinoids (i.e. the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-aracidonylglycerol) and mechanisms for endocannabinoid inactivation (i.e. endocannabinoid uptake and enzymatic degradation by fatty acid amide hydrolase—FAAH).

The CB1 receptor is present in cholinergic nerve terminals of the myenteric and submucosal plexus of the stomach, duodenum and colon, and it is probable that cannabinoid-induced inhibition of digestive tract motility is caused by blockade of acetylcholine release in these areas. There is also evidence that cannabinoids act on CB1 receptors that are localized in the dorsal–vagal complex of the brainstem—the region of the brain that controls the vomiting reflex, explaining anti-emetic effects [27]. Endocannabinoids and their inactivating enzymes are present in the gastrointestinal tract and may also play a physiological role in the control of emesis, although evidence suggests that the central effects may be activated at lower doses of cannabinoids than the peripheral effects [28].

3. Clinical effects of the CB agonists

3.1. Acute effects

Much of our understanding of the acute effects of CB agonists in humans comes from clinical observations and anecdotal reports of persons consuming marijuana. The time course will differ depending on dose and mode of administration; for example, onset of effects will be more rapid following smoking than oral ingestion. However, the qualitative features tend to have similar profiles.

After ingestion by smoking, typical early effects may include light-headedness, dizziness, euphoria, and sometimes visual-perceptual changes. Tachycardia and hypotension may be prominent in some individuals. With passage of time, psychomotor slowing, mild cognitive impairment, especially in the learning of new information, and change in sense of time, are frequently reported. Some individuals experience profound calm and a state of reverie. Others simply feel somewhat sedated or may experience affective lability. Uncommon acute effects include anxiety, panic, paranoia, and psychotic experiences. Many individuals report increase in appetite.

Following ingestion through smoking, initial effects may appear within the first minute, peak at 30–60 min, and gradually dissipate over the next few hours. Oral ingestion has slower onset (e.g. initial effects in 15–30 min, peak effects in 1–3 h, and resolution several hours thereafter).

In animal models, the effects of CB agonists such as THC or synthetic agonists such as WIN-55, 212 and HU 210 produce a characteristic ‘tetrad’ of neurophysiologic changes which include (1) reduced ambulation and rearing, (2) immobility on an elevated ring, (3) hot plate analgesia, and (4) reduction in core body temperature.

In anesthetized rats and dogs, delta-9-THC produces a transient pressor response followed by long-lasting hypotension and bradycardia [29]. The hypotensive effect of delta-9-THC is mimicked by various cannabinoids with a rank order of potency that correlates well with the affinity of the same ligands for the CB1 receptor [30]. Administration of the endocannabinoid anandamide (AEA) to anesthetized rats also produces a brief pressor response that is followed by a more prolonged decrease in blood pressure [31]. The depressor response to AEA is inhibited by coadministration of the SR141716A CB1 receptor antagonist [31] and is absent in CB1 receptor null mice [32] reinforcing the notion that the CB1 receptor is indeed the molecular target responsible for these observed cardiovascular effects.

3.2. Longer-term clinical effects

If the cannabinoids and their analogs become therapeutic agents, and particularly, if they are useful for the treatment of chronic conditions, then the possibility of cumulative toxicity must be considered. In the instance of drugs with psychoactive properties, such as the cannabinoids, the additional issue that their potential for behavioral reinforcement might lead to symptoms of addiction or abstinence syndrome after drug discontinuation must also be considered.

The long-term toxicity of cannabinoids in humans remains largely unknown. The principal reason is that unlike medically used drugs, for which there is a gradual accumulation of information based on reasonably accurate knowledge of cumulative dosage, circumstances of use, and characteristics of patients, most of our knowledge regarding the long-term effects of cannabinoids on humans comes from their uncontrolled recreational use in the form of marijuana. There are some obvious limitations to information gathered in this manner.

3.2.1. Multiple constituents

Human experience with the cannabinoids is based largely on ingestion of plant material, typically in its smoked form. Beyond the major active ingredient, THC, this plant material may consist of as many as 60 other cannabinoids, whose biological properties are not all fully understood. Additionally, there may be other biologically active substances. Thus, even if one were to have accurate estimates of exposure, whatever, effects were observed could not necessarily be attributed to THC or some other molecule. The fact that marijuana is typically smoked also introduces the possible deleterious effects of various products of combustion of plant material, toxicities that may have nothing to do with the cannabinoids per se.

The mix of cannabinoids in plant material poses another challenge. It is possible that in addition to whatever unique action each of these molecules has; they may have effects that interact with each other, either synergistically or antagonistically. For example, cannabidiol, a common constituent of marijuana is known to antagonize THC’s depressant effects on smooth muscle contractility [33]. There are also unconfirmed reports that cannabidiol may antagonize the psychotogenic and anxiogenic effects of higher doses of THC.

3.2.2. THC concentration is variable in plant material

The concentration of THC varies within and across plants. THC can be highly concentrated in mature female unseeded flowers (e.g. 15% of the dry weight of such flowers can be THC and THC-A [34]) with percentage of dry weight declining to 0.8% in the leaves, 0.3% in the stems, and 0% in roots and seeds [34]. The cannabinoid content also differs according to variety of plant, and such potency can be increased by crossbreeding. For instance, it is believed that modern varieties of cannabis grown for recreational use contain ten times the concentration of THC of wild varieties. Secular trends have also been evident. Thus, the typical THC content of a street ‘joint’ is probably several times more potent now than it was several decades ago. These complexities illustrate another level of difficulty in extrapolating from human, naturalistic exposure to marijuana to possible adverse effects. Even if the recall of amount of exposure were accurate, the composition of the material consumed would be difficult to establish.

3.2.3. Developmental stage

The long-term effects of cannabinoids must also depend on the developmental stage at which an organism is exposed. Thus, while there is no solid evidence that adults who smoke marijuana regularly suffer major long-term neurological effects [35] it cannot be concluded that marijuana is ‘safe’ under all circumstances (see Long-term effects on development, below).

3.3. Host factors

The exploration of untoward effects of drugs of abuse, particularly, the neuropsychiatric effects, is complicated by the fact that those who enter careers of use of illicit substances are more prone to have psychiatric disorders to begin with. The comorbidity between heavy substance use and mood disorders, as well as other psychiatric disorders, is well documented. In this sense, it may be difficult to attribute mood disorders to cannabis if the mood disorders actually contributed to initiation of cannabis use in the first place. Similarly, individuals with learning disabilities and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder may experience scholastic and social frustrations that increase their likelihood to experiment with drugs such as cannabis. Again, it is difficult to sort out neurocognitive phenomena that preceded drug use as opposed to those that may be consequences of such.

3.3.1. Comorbid drug use

Regular use of cannabis tends to occur in people who have experience with other legal and illegal recreation drugs. Heavier cannabis users will more likely be tobacco smokers, alcohol users, and a subset of heavy cannabis users will be experienced also with central stimulants, opioids, central nervous system depressants, hallucinogens, and inhalants. Sorting out the individual and joint effects of all these substances is challenging, to say the least.

With these caveats in mind, what is known about the long-term effects of cannabinoids on the nervous system and tissues?

3.4. Long-term effects in adults

In terms of neurologic or neurocognitive effects, it has been difficult to show that there is a consistent, substantial effect of chronic use on neuropsychological functioning. While individual studies sometimes have reported deleterious effects on memory in particular, meta-analytic studies have shown that such effects, if present, are extremely small [35]. This suggests that if agonist compounds were to become medicines, we would expect them to have a good margin of safety even under conditions of longer-term prescription use. Of course, it may be the case that more potent synthetic CB agonists could have deleterious effects that have not been possible to demonstrate with THC and marijuana, either because THC is not as potent a CB binder, or because of some other unique pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.

Cannabinoids can increase susceptibility to viral and protozoal infection in animal models, presumably through their immunosuppressive effects on macrophages, T-lymphocytes, and natural killer cells [36]. Interestingly, even in some animal models the effects on viral infection can differ, depending on the model. For example, Peterson et al. [37] noted that the synthetic cannabinoid agonist WIN 55,212-2 inhibited HIV-1 expression in CD4 and lymphocyte and microglial cell cultures. Nonetheless, the safety of administration of these agents to AIDS and cancer patients might be questioned. Encouragingly, long-term surveys of HIV-positive patients have shown no link between dronabinol (synthetic THC) use or cannabis smoking and average T-cell counts or progression to AIDS [38,39]; and a clinical study in which marijuana was administered under controlled conditions to HIV positive patients also showed no adverse effects on immune functioning [40].

3.5. Long-term effects on development

While observations of adult humans who are regular users of marijuana have failed to demonstrate unequivocal long-term toxicity, it is evident that the cannabinoids, or any other psychoactive drug for that matter, might not be so benign in developing organisms. The few sets of human observations will be reviewed below; however, because of the obvious difficulties in controlling all of the important sources of variation in human studies, animal models might be particularly informative in this instance.

A series of rodent studies have been conducted, generally exposing rats to varying concentrations of THC for differing periods of time during their pre-pubertal stage. Although some studies have failed to detect longer-term impacts on adult behavior, the majority tend to show that chronic high dose exposure of developing rats to THC can produce learning and performance deficits of a type that is similar to that found in animals with certain types of hippocampal lesions [41]. Further, morphometric and neurochemical studies of animals sacrificed after such exposure indicate there may be neuronal injury in the hippocampus as evidenced by breakage of axonodendritic contact regions, with increases in extracellular space, and reduction in synaptic density in the hippocampal CA3 region [41]. Neuronal culture models suggest that THC may produce DNA fragmentation and nuclear shrinkage suggestive of apoptosis [42,43].

The translation of these rodent and in vitro experiments to our understanding of the effects of cannabis, as it is used by people, on child and adolescent development is not straightforward. First, it is evident that even in rodents the demonstration of some of these effects requires prolonged high dosage exposure to THC or its analogs during the maturational period. In terms of dose, typical daily administration ranges from 10–60 mg per kilogram per day of THC. For a 70 kg human, this would mean administering up to 4.2 kg of THC daily (or smoking 420 high quality joints containing 10% THC and delivering 100% bioavailability). While it is recognized that such simple linear transformations are not appropriate given our understanding of higher metabolic rates and generally different kinetics and dynamics in smaller animals, nevertheless, even after such caveats are taken into account, the daily dosages required to produce these effects must be considered impressive.

The proportion of the developing animals’ time exposed to such large amounts of THC must also be noted when considering relevance to the human situation. Rodents must typically be dosed for 3–6 months, i.e. up to 20% of their lifespan. In human terms, considering a life expectancy of 70 years, this would translate into a child or adolescent being exposed daily at high doses for 7–14 years of their developing life, a highly unlikely scenario.

Species differences must also be considered. For example, similar behavioral and neuroanatomic changes have been difficult to demonstrate consistently in primate models of chronic cannabis exposure. Furthermore, rodents may respond more than some other species with significant release of corticosterone to THC administration. Corticosterone itself can produce injury to the hippocampus, which may be difficult to sort out from the direct effects of the cannabinoids.

Given difficulties in extrapolating from animal models, what can be gleaned from the few studies that have been conducted with human development? The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS) has produced several reports that have examined the link between prenatal exposure to cannabis and subsequent child development. Neither in a 5–6-year-old follow-up [44] nor in the 9–12-year-old follow-up [45] did the authors note any relationship between prenatal marijuana exposure and various school achievement measures. Data from the Maternal Health Practices and Child Development study (MHPCD) in Pittsburgh reported possible weak effects for impairment in some measures of academic achievement related to mothers’ use of marijuana in the first and second trimester [46]. However, in that study the authors believed that the child’s anxiety and depression mediated some of this underachievement, and it was not clear what role prenatal marijuana exposure played in such mood changes in the child. Furthermore, though mothers’ education was included in a multivariate model, it was not clear from the report whether parental IQ, which may have an independent effect on child intellectual performance, as well the mother’s decision to use marijuana while pregnant was considered. The complex bidirection-alities of cannabis and neurodevelopmental trajectory were illustrated in a report by Pedersen et al. [47], which was based on a prospective longitudinal study of a national sample of 2436 adolescents in Norway. The authors found that early conduct problems in children were significant predictors of later initiation of cannabis use. While neurocognitive measures were not reported, based on other research it might be expected that children with early conduct problems may score worse on scholastic and neuropsychological tests. As these would also be the children more likely to initiate cannabis use, a difficulty arises in subsequently sorting out the effects of dispositional factors and drug on adolescent intellectual development.

In summary, rodent models suggest that heavy prolonged exposure of developing animals to THC can produce neurobehavioral deficits and neuroanatomic changes, particularly in the hippocampus. There are insufficient data from primate models to reach conclusions on THC’s effect on primate development. The translation from animal models to typical human experience, given species-specific differences, large dosages and chronicity of use required, is questionable. Current human observations on the effects of marijuana on development are sparse and contradictory.

4. Addiction potential of cannabinoids

It is a common observation that humans find their experience with the cannabinoids in the form of marijuana to be sufficiently rewarding that some of them choose to revisit the experience at least on an occasional basis, with a smaller proportion becoming regular users. Increasingly, animal models have begun to delineate the molecular and physiological bases for this reinforcement; however, translation from such models to the human experience has proved difficult. Initially, animal models based on administration of THC provided inconclusive results, depending on species and exact conditions of administration. The discovery of CB receptor antagonists provided the first clear-cut demonstrations that animals chronically exposed to THC or synthetic agonists could be precipitated into a withdrawal state by such antagonists.

The lines of evidence from animal models indicating that THC and the CB1 agonists share some of the motivational and reinforcing properties of other drugs of abuse have been summarized by Maldonado and Rodríguez de Fonseca [48]. Thus, THC can be demonstrated to provide selective discriminative stimulus effects, which can be prevented by the CB1 antagonist SR141716A. Under suitable conditions, animals will demonstrate preference for THC, which can also be suppressed by CB1 blockade. Interestingly, conditioned place preference is suppressed in μ-opioid receptor knockout mice, indicating interplay between the opioid and the cannabinoid systems. It should be noted that preference is dose dependent (animals find higher doses of THC to be aversive) and also dependent on pre-exposure (naïve animals tend to find THC aversive).

To a variable degree THC can be shown to enhance intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS), the magnitude of the effect differing across species. Once again, CB1 blockade reduces THC induced ICSS and naloxone can block THC enhancement of ICSS. While intravenous self-administration (IVSA) paradigms involving THC itself have proved to be unreliable, experiments with synthetic CB1 agonists such as WIN 55 212-2 can produce IVSA, which is prevented by CB1 antagonists, and, in some species by opioid antagonists, as well.

Animal models also indicate that tolerance develops to the chronic administration of CB1 agonists. This tolerance extends to their hypothermic, analgesic, anticonvulsant, cataleptic, and cardiovascular effects. Chronic administration of CB1 agonists results in reduced density and sensitivity of CB1 receptors.

In terms of withdrawal phenomena, animal experiments with chronic THC administration were not able reliably to produce an abstinence syndrome. However, sudden discontinuation of the synthetic agonists can produce such a syndrome, which is best elicited through administration of CB1 antagonists. In rodents, various locomotor signs of withdrawal have been observed including ‘wet dog shakes’, hyperlocomotion, ataxia, front paw rubbing, licking, biting, and scratching.

There are fewer data in regard to tolerance and withdrawal symptoms in humans. Evidence from a handful of interview and clinical laboratory studies indicate that sudden discontinuation of regular use of marijuana can result in irritability, nervousness, tension, restlessness, reduced appetite, sleep difficulties, dysphoria, and possibly craving [49,50]. These data are reviewed in detail by Budney et al. [51].

These symptoms have some characteristics in common with, albeit are much less severe than those experienced in opioid withdrawal. A notable difference between cannabinoid abstinence and opioid abstinence is the presence of severe physiological manifestations in the latter, not found in the former. These include opioid withdrawal related symptoms such as achiness, piloerection, diarrhea, sweating, stuffy nose, muscle spasms, etc.

In summary, tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal effects can be demonstrated in certain animal models, and have also been reported in humans. The pharmacokinetics, and perhaps the pharmacodynamics of THC (e.g. slow elimination of THC and its byproducts) may attenuate withdrawal to a subclinical level among humans, thus the effect not being notable in any except very heavy users who suddenly discontinue. As cannabinoids advance into medical practice, the synthetic CB agonists, having different kinetics and dynamics, may produce more (or perhaps less) signs of tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal. As such agents are developed and evaluated, the complex interactions between the cannabinoid and opioid systems will require continued study.

5. Marijuana and cannabinoids as medicine

Although references to potential medicinal properties of cannabis date to ancient times, and despite cannabis being included as a medication in Western pharmacopeias from the nineteenth through the early twentieth centuries, there is still no body of reliable information on possible indications or efficacy. In part, slow progress can be attributed to difficulties in identifying the active ingredients in cannabis; THC was not actually characterized and identified as the main psychoactive substance until 1965. The chemical properties of the cannabinoids, for example their virtual insolubility in water, and the fact that they consist of oily liquids at room temperature has posed further challenges in formulation and administration. Increased governmental concerns about the abuse potential of marijuana and hashish also created a regulatory climate in many Western countries that emphasized the negative properties of these substances and absence of any documented medicinal properties, thus discouraging research into therapeutics.

Cultural and attitude changes in the latter half of the twentieth century in many Western countries resulted in large groups of ‘mainstream’ adults and adolescents experimenting with marijuana. The scarcity of obvious acute serious toxic effects, and lack of consistent information on longer-term adverse effects has lead to more recent attitudinal changes in many Western societies that have re-opened the possibility of use of cannabis as a medication.

For example, the ninth report for the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology of the British Parliament in 1998 concluded that cannabis most probably did have genuine medical applications that clinical trials of cannabis for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and chronic pain should be mounted as a matter of urgency, that cannabis should be reclassified to a less restrictive schedule, and that research should be promoted into alternative modes of administration [52]. Similarly, the report of the Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs of the Parliament of Canada recommended that Health Canada amend the Marijuana Medical Access Regulations to allow compassionate access to cannabis and its derivatives. More specifically, the Committee called for new rules regarding eligibility, production, and distribution with respect to cannabis for therapeutic purposes, and stated that research on cannabis for therapeutic purposes was ‘essential’[53]. More recently still, the Netherlands in March 2003 changed its opium law to allow doctors to prescribe cannabis through pharmacies. In the USA, an increasing number of states, mostly in the West passed laws or initiatives permitting patients to have access to marijuana for medicinal purposes with physician prescription. The status of these state laws remains in doubt as contradictory court decisions continue to try to resolve whether state or federal statutes are preeminent. In California, one spin-off of the voter passed ‘Compassionate Use Act’(Proposition 215), which envisions access to marijuana for patients under medical supervision, was the establishment in 1999 by the legislature of the State of California of the Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research (CMCR) at the University of California. The CMCR represents the first comprehensive program in clinical research on marijuana ever to be conducted in the United States and is currently supporting approximately 12 clinical studies with patients with various disorders including severe AIDS (and other) related peripheral neuropathy, spasticity in multiple sclerosis, and delayed nausea and vomiting in cancer. Similarly, as a follow-on to Canada’s Senate Report, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research is considering applications for the first modern era clinical trials of cannabis in that country.

5.1. Results of earlier research with cannabis, THC, and its synthetic analogs (1970s–early 1990 s)

The results of earlier clinical studies have been reviewed thoroughly in several reports, and will not be presented in detail here [52–55]. In brief, there were contradictory findings in human studies on pain, with some research suggesting that THC relieved cancer pain about as well as 60 mg of codeine [56,57] and that levonantrodol, a synthetic THC-like cannabinoid was effective in post-operative and trauma pain [58]. On the other hand, Raft et al. [59] found no effect of THC on the pain of tooth extraction, and Clark et al. [60] found some suggestion that moderate to high doses of THC actually produced hyperalgesia.

A number of the earlier studies examined the effects of THC and its analogs on chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. Generally speaking, THC and its analogs were found to be somewhat effective [61,62]. The efficacy of THC, nabilone, and levonantrodol (synthetic analogs of THC) was comparable to that of prochlorperazine [63–66], but not as good as that of metoclopramide [67]. The results were sufficiently favorable that in 1985 the US FDA approved dronabinol (synthetic THC) for use in nausea and vomiting.

In the 1990 s, clinical trials indicated that dronabinol could improve appetite and increase weight in cancer cachexia [68] and was useful in improving the nutritional status and appetite in persons with advanced HIV disease and AIDS wasting [69–71]. The FDA approved dronabinol as an appetite stimulant for AIDS related weight loss in 1992.

Considerable anecdotal evidence and some animal studies have suggested that the cannabinoids might be useful in treatment of spasticity, movement disorders, or dystonias. Until recently, there have been very few properly designed studies, and their results have been contradictory [54]. Anecdotal reports of possible marijuana benefits have been particularly numerous in regard to spasticity and tremor of multiple sclerosis. However, prior to the early 1990 s only one placebo controlled trial was completed with patients with multiple sclerosis [72]. This study involved 13 patients with MS and spasticity. The authors concluded that doses of THC at 7.5 mg daily or above produced significant improvement in spasticity, compared to placebo.

5.2. Recent and on-going studies with cannabis, THC, and their synthetic analogs

Stimulated by the increased pace of discoveries related to the endocannabinoid system, and supported by changes in social acceptance of the possibility of the cannabinoids as medicines in many industrialized countries, there has been a renewal of interest and activity in clinical research on cannabis and related substances. The results of an entire program of research from the Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research at the University of California should be forthcoming in the next several years. These studies involve primarily smoked marijuana. In the United Kingdom and Europe several trials have been conducted with novel oral-mucosally administered extracts of cannabis, involving approximately equal amounts of THC and cannabidiol (approximately 2.5 mg of each) delivered through a metered dose device (Sativex-GW Pharmaceuticals). The initial results of experience with Sativex are beginning to be reported.

In a study of 160 outpatients with multiple sclerosis, there was no significant benefit for Sativex versus placebo on the primary outcome measure, a visual analog scale score for the patient’s most troublesome symptom. However, the authors do report significant reduction in self-reported spasticity. A second group of patients with MS were evaluated for changes in symptoms of bladder dysfunction during an open label study [73]. Improvement was noted in number of incontinence episodes, urinary frequency, and nocturia.

Three other studies with cannabinoids and multiple sclerosis have recently been reported. The results have been marginal or ineffective. A study of 16 patients found no treatment benefit for spasticity and worsened patient global impression score [74.] A study of 57 patients by Vaney et al. [75] found no statistically significant difference to placebo in the intention to treat analysis, although sub-analyses suggested some benefit for spasticity ratings. Similarly, a large multi-site study of 630 patients randomly assigned to receive THC, cannabis extract, or placebo failed to demonstrate improvement in spasticity on objective rating. However, self-report ratings did suggest some benefit, and there was a suggestion that the THC group had improvement in walking [76]. In summary, newer studies on multiple sclerosis spasticity continued to show inconsistent, and, at best, modest results. Two CMCR studies are still ongoing and these may help determine whether it might be useful to pursue molecules based on the cannabinoids in future MS studies.

In regard to newer studies on pain, Berman et al. [77] reported on the results of two GW produced mucosal sprays, Sativex (about equal composition THC and cannabidiol) and GW2000-02 (primarily THC) in 48 patients with neuropathic pain from brachial plexus avulsion. Based on the primary outcome measure, which was a fall of at least 2 points in a mean pain severity score, both active treatments were not effective. There were, however, were some improvements both in pain and sleep measures. Again, these data suggest at best modest therapeutic efficacy of these cannabinoid preparations.

In regard to movement disorders, historic data have not been promising. A recent study of cannabis extract failed to show improvement in Parkinsonian dyskinesia [78].

5.3. Potential therapeutic opportunities with novel agonists, antagonists and modifiers of endocannabinoid transport and metabolism

Following the discovery of the cannabinoids and some of their molecular targets, it is now clear that in theory, at least, the diseases and illnesses that may be susceptible to treatment via modulation of cannabinoid system are many. This is evidenced by the recent proliferation of lengthy reviews on the clinical implications for cannabinoid therapeutics [38,79–86]. The list of conditions includes gastrointestinal disorders (including inflammatory bowel disease), obesity, asthma, glaucoma, cancer, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis and other diseases of defective immunomodulation, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, cystic fibrosis, stress-related disorders, nausea, vomiting, drug addiction, and pain. A brief review of the main possibilities and their possible molecular mechanisms follow below.

5.4. Appetite

Anandamide is capable of increasing food intake in rats [87], while the antagonist SR-141716A inhibits the intake of food [88–90] and is currently being evaluated as an anti-obesity treatment with good results (see below). The underlying circuitry responsible for the therapeutic efficacy of cannabinoids in stimulating appetite is not yet known, although it is probably related to the fact that the CB1 receptor, anandamide, and 2-AG are present in the hypothalamus, which is known to be associated with feeding [91]. It is of note that evidence for a function of the endogenous cannabinoid system in feeding has been obtained for the primitive invertebrate Hydra vulgaris [92], pointing to a very ancient history of the endocannabinoid system in the regulation of feeding, greatly preceding the evolution of the hypothalamic control of appetite seen in vertebrates.

One of the currently accepted uses of cannabinoid therapy in the US and many European countries is a synthetic delta-9-THC preparation (dronabinol, Marinol) and its synthetic analogue LY109514 (nabilone, Cesamet), both of which are approved in several counties primarily for nausea and emesis associated with cancer chemotherapy but also used for the stimulation of appetite in cancer and HIV infection. Studies have found dronabinol to be effective in stimulating appetite in both cancer patients [93] and HIV infected patients [94]. Interestingly, endocannabinoids are present in breast milk, 2-AG levels being much higher than those of anandamide [95].

Regarding possible treatment for obesity mediated through the cannabinoid system, the Sanofi-Synthelabo Research group recently presented the results of a phase III clinical trial on the effects of the selective CB1 antagonist SR141716A (Rimonabant) in obese patients with hyperlipidemia [96]. While Rimonabant had no effect on taste, it induced a significant decrease of hunger, caloric intake, and body weight in obese patients in comparison with placebo—72% of the patients showed at least a 5% reduction in weight and 44% of patients at least a 10% reduction. Impressively there was also an increase in HDL cholesterol, a decrease in triglyceride values and reductions in both glucose and insulin values after an oral glucose tolerance test. These results indicate that Rimonabant may become a therapeutic drug in obesity in the near term.

5.5. Gastrointestinal

Historically, marijuana was prescribed for the treatment of diarrhea as well as inflammatory diseases of the bowel [97]. It now appears that the range of gastrointestinal disorders that may be amenable to treatment with cannabinoid therapeutics is quite broad, including nausea and vomiting, gastric ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, secretory diarrhea, paralytic ileus and gastroesophageal reflux disease [26,98].

The therapeutic possibilities of cannabinoids have been demonstrated in a number of these diseases in both animal models and clinical trials. For example, a recent report showed that experimental colitis is more severe in CB1-deficient mice than in wild-type littermates, and furthermore, that pre-treatment with a CB1 antagonist in wild-type mice elicits a similar potentiated susceptibility to this experimental colitis model [97]. Further recent evidence suggests the possibility that CB2 receptors in the rat intestine can help reduce the increase of intestinal motility induced by endotoxic inflammation [99]. By minimizing the adverse psychotropic effects associated with brain cannabinoid receptors, the CB2 receptor represents a promising molecular target for the treatment of motility disorders from the perspective of reduced side effects.

5.6. Cardiovascular

It has been long recognized that the cannabinoids produce cardiovascular effects in vivo. In humans, the most consistent cardiovascular effects of both marijuana smoking and i.v. administration of delta-9-THC are peripheral vasodilation and tachycardia [29]. These effects manifest themselves as an increase in cardiac output, increased peripheral blood flow, and variable changes in blood pressure (usually reduced).

What is less well recognized, but of potential clinical importance, is that a variety of observations suggest that endocannabinoids have protective effects on the cardiovascular system particularly in shock and myocardial ischaemia [100]. For example, CB1 antagonism increases blood pressure and decreases survival time in rats, which are in hemorrhagic shock as a result of the removal of 50% of blood volume whereas cannabinoid agonists increase survival [101]. Recent evidence suggests that cannabinoids reduce infarct size associated with ischaemia/reperfusion in rat-isolated hearts and the effect is blocked by CB antagonists SR141716A or SR144528 [100]. In the next few years, there is likely to be a concerted effort to uncover the molecular determinants of this cardioprotective effect, opening up the doorway to the application of cannabinoidergic modulators in the treatment of cardiovascular disease.

5.7. Cancer

The antiproliferative properties of cannabis compounds were first reported almost 30 years ago by Munson et al. [102], who showed that THC inhibits lung–adenocarcinoma cell growth in vitro and after oral administration in mice. Further studies in this area were not carried out until the late 1990 s. Several plant-derived (for example, THC and cannabidiol), synthetic (for example, WIN-55, 212-2 and HU-210) and endogenous cannabinoids (for example, anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol) are now known to exert antiproliferative actions on a wide spectrum of tumour cells in culture [103,104]. More importantly, cannabinoid administration slows the growth of various tumour xenografts, including lung carcinomas, gliomas, thyroid epitheliomas, skin carcinomas and lymphomas. The molecular determinants for these processes is not yet known and quite complicated, varying depending on the cancer cell type or process studied. One process that has been observed in both in vivo and in vitro studies of glioma is that cannabinoid agonists were shown to activate apoptosis in transformed cells through ERK signaling and AKT pathways, resulting the production of ceramide and subsequent apoptotic cell death [105,106]. Other observed processes in conjunction with reduced cancerous growth include sustained adenylyl cyclase inactivation and ERK activation with decreased growth-factor receptor signaling and decreased angiogenesis and metalloproteinase expression [103]. As these processes are delineated, the possible role of phyto and synthetic cannabinoids and other CB1 agonists as antineoplastics will need to be explored.

5.8. Neuroprotection

There is evidence supporting a neuroprotective role for cannabinoids, and some of this is presented in the subsequent section on Multiple Sclerosis. It seems that the endocannabinoid system facilitates neuroprotective activity at baseline and can be upregulated when injury occurs [107–109]. In support of the general finding that cannabinoids act in a neuroprotective manner, glutamate toxicity has been shown to be reduced in mice pretreated with either THC or cannabidiol [110,111]. In support of the role of the endocannabinoid system in providing neuroprotective relieffrom brain injury, it has been reported that rat neonatal brain produces significantly more anandamide and its phospholipid precursor after injury than controls [112] whereas, experimental stroke has been found to cause the induction of CB1 receptor expression [113]. After a relatively mild head trauma, anandamide, but not 2-AG, levels in young rat brains were found to be significantly elevated [114]. In addition, others have found that closed head injury (CHI) in mice causes strong enhancement of 2-AG production and that exogenous 2-AG administration after CHI in mice leads to significant reduction of brain edema, better clinical recovery, reduced infarct volume and reduced hippocampal cell death compared with controls [115]. In farct volumes of spontaneously hypertensive rats subjected to permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion were smaller in animals treated with dexanabinol [116]. In sum, it appears that the cannabinoid system is upregulated in response to various brain insults, perhaps representing an attempt to provide endogenous neuroprotective actions, and it is likely that therapeutic strategies based on modifying endocannabinoid activity will prove useful.

5.9. Multiple sclerosis

The studies on neuroinflammation in animal models of multiple sclerosis have been encouraging. Data from experiments with rats and guinea-pigs [117,118] have indicated that cannabinoid agonists decrease signs of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a mouse model of MS. Mouse studies of EAE have shown decreased neurodegeneration from the administration of cannabinoid agonists and greatly increased susceptibility to the disease in CB1-Knock out mice, and the important neuroprotective role of CB1 (as evidenced by greatly increased neurodegeneration in CB1-KO mice) has been a focus in such studies [119]. A variant of EAE and second model of MS, chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (CREAE), has shown very robust sensitivity to cannabinoid agents as well. For example, Baker et al. [120] have investigated the role of CB1 vs. CB2 cannabinoid receptors in cannabinoid-induced suppression of the spasticity and tremor of mice with CREAE, reporting that both CB1 and CB2 receptors may play a role—CB2 possibly through their presence on immune cells in the CNS which may be signaled to down-regulate their reactivity through cannabinoid agonism [120,121].

Clinical studies on marijuana and cannabinoids in the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) have focused on the reduction of muscle spasticity and pain. Unlike the preclinical data, human studies have shown mixed results, as noted above. It remains to be seen whether novel molecules, optimized for modifying neural excitability, inflammation, or both may be useful in MS treatment. Future trials may need to differentiate patients who have more signs of inflammation (e.g. relapsing–-remitting cases) versus neuronal injury (e.g. progressive cases). For example, is it possible that upregulation of microglial CB2 receptors early in the course of disease might reduce inflammatory injury in the CNS? [122].

5.10. Pain

The cannabinoid signaling system functions as a parallel but distinct mechanism from the opioids in modulating pain responses. Once again, the preclinical research which indicates strong anti-nociceptive effects in a number of animal models is much more convincing than the clinical trials to date. For example, in the animal models the antinociceptive potency of delta-9-THC is no less than that of morphine, an agent known to induce receptor-mediated analgesia, and a number of cannabinoids show even greater potency than delta-9-THC in specific pain tests [123].

Human pain studies with marijuana and THC analogues have produced results that are weaker than animal data would predict. Evident sources of variation that need to be addressed are nature of pain (e.g. surgical, inflammatory, neuropathic) and the possibility that there is an inverted U shaped effect (e.g. medium dose is antinociceptive, high dose is hyperalgesic), and the possibility that for some types of pain the cannabinoid agonists exert their effects through non-CB receptor mechanisms. In this regard, Salim et al. [124] have shown that a synthetically modified compound derived from the THC metabolite THC-11-oic acid, termed ajulemic acid, may have analgesic and anti-allodynic effects. Ajulemic acid does not bind strongly to CB receptors and does not have psychotropic effects. Salim et al. [124] suggest that its antinociceptive action might involve inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. Similarly, the endogenous anandamide analogue N-palmatoylethanolamine (PEA) appears to exhibit anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects in experimental models of neuropathic, inflammatory and visceral pain through non-CB1 or CB2 receptor mechanisms [28].

5.11. Stress and anxiety

Several converging lines of evidence suggest cannabinoid therapeutic possibilities in the treatment of stress-related disorders. One study of animal models using a fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitor to potentiate endogenous levels of cannabinoid signaling has substantiated this. FAAH inhibitors interfere with hydrolysis of anandamide, increasing its availability. The FAAH Inhibitor URB597 does not display a typical cannabinoid profile in live animals but does exert several pharmacological effects that might be therapeutically relevant. One such effect, the ability to reduce anxiety-like behaviors in rats, was demonstrated in the elevated ‘zero maze’ test, and the isolation-induced ultrasonic emission test [125]. The ‘zero maze’ is based on the conflict between an animal’s instinct to explore its environment and its fear of open spaces where it may be attacked by predators. Benzodiazepines and other clinically used anxiolytic drugs increase the proportion of time spent in, and the number of entries made into, the open compartments and in a similar fashion, URB597 elicits anxiolytic-like responses at a dose (0.1 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) that corresponds to that required to inhibit brain FAAH activity. These effects are prevented by the CB1-selective antagonist SR141761A. Similar results were obtained in the ultrasonic vocalization emission test, which measures the number of stress-induced vocalizations emitted by rat pups removed from their nest. These results suggest that inhibition of intracellular FAAH activity may offer an innovative target for the treatment of anxiety [126], which is also a feature of marijuana withdrawal [50,51,127]. Forebrain sites that might be implicated in such actions include the basolateral amygdala, the anterior cingulate cortex and the prefrontal cortex, all key elements of an ‘emotion circuit’ that contains high densities of CB1 receptors [18,19].

5.12. Drug addiction

While the development of a rodent model of delta-9-THC self-administration has so far been unsuccessful [128], it is clear that the endocannabinoid system, acting through CB1, is actively involved in the dopaminergic mesolimbic brain reward circuit [128,129]. Cannabinoids enhance the release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, an effect due to an enhanced firing of mesolimbic dopaminergic neurons [130]. Within the central nervous system, the D2 and CB1 receptors are densely expressed in the basal ganglia [131] and recent results indicate that the acute drug-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) is in fact mediated by CB1 receptors for a wide class of abused drugs [128,132]. For example, alcohol-induced increase in dopamine in nucleus accumbens dialysates in C57BL/6 mice was completely inhibited by pre-treatment with the SR141716A or deletion of CB1 receptors in mice (CB1 receptor knockout), suggesting an interaction between the cannabinoidergic and dopaminergic systems in the reinforcing properties of alcohol addiction [132,133].

Findings from preclinical studies suggest that ligands blocking CB1 receptors (e.g. SR 14176A/Rimonabant) might offer a novel and possibly efficacious approach for patients suffering from drug dependence that may be efficacious across different classes of abused drugs.

5.13. Glaucoma

Cannabinoids have the potential of becoming a useful treatment for glaucoma, as they seem to have neuroprotective properties and effectively reduce intraocular pressure. The converging evidence supporting their use for not only intraocular pressure but also for their neuroprotective effects has prompted a number recent reviews highlighting their promise for this eye disorder [134–136]. Pharmacological and histological studies support the direct role of ocular CB1 receptors in the intra-ocular pressure (IOP) reduction induced by cannabinoids. The anatomical distribution of cannabinoid receptors suggests a possible influence of endogenous cannabinoids on aqueous humour outflow and on aqueous humour production. Despite the earlier belief in a central mediation of the effects of cannabinoids on IOP, recent work has now shown that it the effects are local in nature—for example, two groups have shown that the IOP-lowering effect of topically-applied synthetic CB1 agonists can be antagonized by topically pretreating the animals with the CB1 antagonist SR [137,138].

5.14. Summary

The discovery of an endocannabinoid signaling system has opened new possibilities for research into understanding the mechanisms of marijuana actions, the role of the endocannabinoid system in homeostasis, and the development of treatment approaches based either on the phytocannabinoids or novel molecules. CB1 agonists may have roles in the treatment of neuropathic pain, spasticity, nausea and emesis, cachexia, and potentially neuroprotection after stroke or head injury. Agonists and antagonists of peripheral CB receptors may be useful in the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, as well as hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases. CB1 antagonists may find utility in management of obesity and drug craving. Other novel agents that may not be active at CB receptor sites, but might otherwise modify cannabinoid transport or metabolism, may also have a role in therapeutic modification of the endocannabinoid system. While the short and long term toxicities of the newer compounds are not known, one must expect that at least some of the acute effects (psychotropic effects; hypotension) may be shared by CB agonists. While there are few, long-term serious toxicities attributable to marijuana, extrapolation to newer and more potent agonists, antagonists, and cannabinoid system modulators cannot be assumed. CB1 agonists have the potential in animal models to produce drug preference and drug seeking behaviors as well as tolerance and abstinence phenomena similar to, though not generally as severe as those of other drugs of addiction. There is increasing evidence from human observations that withdrawal from the phytocannabinoids can produce an abstinence syndrome characterized primarily by irritability, sleep disturbance, mood disturbance, and appetite disturbance in chronic heavy users, therefore, such possible effects will need to be considered in the evaluation of newer shorter acting and more potent agonists.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the University of California Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research and in part by the NIGMS Medical Scientist Training Grant #T32 GM07198.

References

- 1.Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. Isolation, structure and partial synthesis of an active constituent of hashish. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:1646–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlett AC, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Milne GM. Nonclassical cannabinoid analgetics inhibit adenylate cyclase: development of a cannabinoid receptor model. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;33(3):297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–4. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, et al. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munro SK, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannbinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–5. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanus L, Gopher A, Almog S, Mechoulam R. Two new unsaturated fatty acid ethanolamides in brain that bind to the cannabinoid receptor. J Med Chem. 1993;36:3032–4. doi: 10.1021/jm00072a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugiura T, Kondo S. Sukagawa A2-Ar. rachidonylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;215:89–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mechoulam R, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, et al. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang SY, Bridges D, Gigorenko E, McCloud S, Boon A, Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA. Cannabinoids produce neuroprotection by reducing intracellular calcium release from ryanodine-sensitve stores. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1086–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hohmann AG, Herkenham M. Localization of central cannabinoid CB1 receptor messenger RNA in neuronal subpopulations of rat dorsal root ganglia: a double-label in situ hybridization study. Neuroscience. 1999;90:923–31. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farquhar-Smith WP, Egertova M, Bradbury EJ, McMahon SB, Rice AS, Elphick MR. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor expression in rat spinal cord. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;15:510–21. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahluwalia J, Urban L, Capogna M, Bevan S, Nagy I. Cannabinoid 1 receptors are expressed in nociceptive primary sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 2000;100:685–8. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iversen L, Chapman V. Cannabinoids: a real prospect for pain relief? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2(1):50–5. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(01)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malan TP, Ibrahim MM, Deng H, Liu Q, Mata HP, Vanderah T, Porreca F, Makriyannis A. CB2 cannabinoid receptor-mediated peripheral antinocieption. Pain. 2001;93:239–45. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fride E, Shahomi E. The endocannabinoid system: function in survival of the embryo, the newborn and the neuron. NeuroReport. 2002;13(15):1833–41. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200210280-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fride E, Ginzburg Y, Breuer A, Bisogno T, Di Marzo V, Mechoulam R. Critical role of the endogenous cannabinoid system in mouse pup suckling and growth. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;419:207–14. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berrendero F, Sepe N, Ramos JA, Di Marzo V, Fernández-Ruiz JJ. Analysis of cannabinoid receptor binding and mRNA expression and endogenous cannabinoid contents in the developing rat brain during late gestation and early postnatal period. Synapse. 1999;33:181–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990901)33:3<181::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Little MD, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1932–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glass M, Dragunow M, Faull RL. Cannabinoid receptors in the human brain: a detailed anatomical and quantitative autoradiographic study in the fetal, neonatal and adult human brain. Neuroscience. 1997;77:299–318. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00428-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katona I, Rancz EA, Acsady L, Ledent C, Mackie K, Hajos N, Freund TF. Distribution of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in the amygdala and their role in the control of GABAergic transmission. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9506–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09506.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arévalo C, de Miguel R, Hernández-Tristán R. Cannabinoid effects on anxiety-related behaviours and hypothalamic neurotransmitters. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:123–31. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Carrera MRA, Navarro M, Koob GF, Weiss F. Activation of corticotropin-releasing factor in the limbic system during cannabinoid withdrawal. Science. 1997;276:2050–4. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Maldonado R, Valverde O. Involvement of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in emotional behaviour. Psychopharmacology. 2002;159:379–87. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haller J, Bakus N, Szirmay M, Ledent C, Freund TF. The effects of genetic and pharmacological blockade of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor on anxiety. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1395–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marsicano G, Wotjak CT, Azad SC, et al. The endogenous cannabinoid system controls extinction of aversive memories. Nature. 2002;418:530–4. doi: 10.1038/nature00839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Carlo G, Izzo AA. Cannabinoids for gastrointestinal diseases: potential therapeutic applications. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12(1):39–49. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Sickle MD, Oland LD, Ho W, et al. Cannabinoids inhibit emesis through CB1 receptors in the brainstem of the ferret. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:767–74. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darmani NA, Izzo AA, Degenhardt B, Valenti M, Scaglione G, Capasso R, Sorrentini I, Di Marzo V. Implication of the cannabimimetic compound, N-palmitoylethanolamine, in inflammatory and neuropathic conditions. A review of the available preclinical data, and first human studies. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1154–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dewey WL. Cannabinoid pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1986;38:151–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lake KD, Compton DR, Varga K, Martin BR, Kunos G. Cannabinoid induced hypotension and bradycardia in rats mediated by CB1-like cannabinoid receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:1030–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varga K, Lake K, Martin BR, Kunos G. Novel antagonist implicates the CB1 cannabinoid receptor in the hypotensive action of anandamide. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;278:279–83. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00181-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarai Z, Wagner JA, Varga K, et al. Cannabinoid-induced mesenteric vasodilation through an endothelial site distinct from CB1 or CB2 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14136–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pertwee RG, Thomas A, Stevenson LA, Maor Y, Mechoulam R. (−)-7-hydroxy-4’-dimethylheptyl-cannabidiol activates a non-CB1, non-CB2, non-TRPV1 target in the mouse vas deferens in a cannabidiol-sensitive manner. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potter D. Growth and morphology of medicinal cannabis. In: Guy GW, Whittle BA, Robson PJ, editors. The medicinal uses of cannabis and cannabinoids. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2004. pp. 17–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant I, Gonzalez R, Carey C, Natarajan L, Wolfson T. Non-acute (residual) neurocognitive effects of cannabis use: A meta-analysis study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9:679–89. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703950016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cabral GA, Dove Pettit DA. Drugs and immunity: cannabinoids and their role in decreased resistance to infectious disease. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;83(1–2):116–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterson PK, Gekker G, Hu S, Cabral G, Lokensgard JR. Cannabinoids and morphine differentially affect HIV-1 expression in CD4(+) lymphocyte and microglial cell cultures. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;147(1–2):123–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robson P. Therapeutic aspects of cannabis and cannabinoids. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:107–15. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh D, Nelson KA, Mahmoud FA. Established and potential therapeutic applications of cannabinoids in oncology. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11:137–43. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abrams DI, Hilton JF, Leiser RJ, et al. Short-term effects of cannabinoids in patients with HIV-1 infection: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(4):258–66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-4-200308190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scallet AC. Neurotoxicology of cannabis and THC: A review of chronic exposure studies in animals. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:671–6. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90380-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan GCK, Hinds TR, Impey S, Storm DR. Hippocampal neurotoxiticy of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5322–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05322.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ameri A. The effects of cannabinoids on the brain. Progress in Neurobiology. 1999;58:315–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fried PA, O’Connell CM, Watkinson B. 60- and 72-month follow-up of children prenatally exposed to marijuana, cigarettes, and alcohol: cognitive and language assessment. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1992;13(6):383–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fried PA, Watkinson B, Siegel LS. Reading and language in 9- to 12-year olds prenatally exposed to cigarettes and marijuana. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1997;19(3):171–83. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(97)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Cornelius MD, Day NL. Prenatal marijuana and alcohol exposure and academic achievement at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:521–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pedersen W, Mastekaasa A, Wichstrom L. Conduct problems and early cannabis initiation: a longitudinal study of gender differences. Addiction. 2001;96(3):415–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9634156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maldonado R, Rodríguez de Fonseca F. Cannabinoid addiction: Behavioral models and neural correlates. J of Neuroscience. 2002;22(9):3326–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03326.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Budney AJ, Novy PL, Hughes JR. Marijuana withdrawal among adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 1999;94:1311–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kouri EM, Pope HG., Jr Abstinence symptoms during withdrawal from chronic marijuana use. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8(4):483–92. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, Vandrey R. Review of the validity and significance of cannabis withdrawal syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1967–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cannabis: The scientific and medicinal evidence. Stationery Office; London: 1998. House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology. Ninth Report. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Canadian Senate Report. Cannabis: Our position for a Canadian public policy - report of the Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs, Canadian Parliament. 2002 http://www.parl.gc.ca/common/Committee_SenRep.asp?Language=E&Parl=37&Ses=1&comm_id=85.

- 54.National Academy of Science, Institute of Medicine. The medical value of marijuana and related substances. In: Joy JE, Watson SJ Jr, editors. Marijuna and Medicine, Assessing the Science Base. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guy GW, Whittle BA, Robson PJ. The medicinal uses of cannabis and cannabinoids. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noyes R, Jr, Brunk SF, Baram DA, Canter A. Analgesic effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;15(2–3):139–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1975.tb02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noyes R, Jr, Brunk SF, Avery DH, Canter A. The analgesic properties of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and codeine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1975;18:84–9. doi: 10.1002/cpt197518184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jain AK, Ryan JR, McMahon FG, Smith G. Evaluation of intramuscular levonantradol and plecebo in acute postoperative pain. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:320S–36. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raft D, Gregg J, Ghia J, Harris L. Effects of intravenous tetrahydrocannabinol on experimental and surgical pain: Psychological correlates of the analgesic response. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977;21:26–33. doi: 10.1002/cpt197721126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark WC, Janal MN, Zeidenberg P, Nahas GG. Effects of moderate and high doses of marihuana on thermal pain: A sensory decision theory analysis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:299S–3310. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang AE, Shiling DJ, Stillman RC, et al. A prospective evaluation of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in patients receiving adriamycin and cytoxan chemotherapy. Cancer. 1981;47:1746–51. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810401)47:7<1746::aid-cncr2820470704>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vinciguerra V, Moore T, Brennan E. Inhalation marijuana as an antiemetic for cancer chemotherapy. N Y State J Med. 1988;88(10):525–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orr LE, McKernan JF, Bloome B. Antiemetic effect of tetrahydrocannabinol. Compared with placebo and prochlorperazine in chemotherapy-associated nausea and emesis. Arch of Internal Medicine. 1980;140:1431–3. doi: 10.1001/archinte.140.11.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sallan SE, Cronin C, Zelen M, Zinberg NE. Antiemetics in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer: a randomized comparison of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and prochlorperazine. N Engl J Med. 1980;302(3):135–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198001173020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steele N, Gralla RJ, Braun DW, Jr, Young CW. Double-blind comparison of the antiemetic effects of nabilone and prochlorperazine on chemotherapy-induced emesis. Cancer Treat Rep. 1980;64(2–3):219–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tyson LB, Gralla RJ, Clark RA, Kris MG, Bordin LA, Bosl GJ. Phase 1 trial of levonantradol in chemotherapy-induced emesis. Am J Clin Oncol. 1985;8(6):528–32. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198512000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gralla RJ, Tyson LB, Bordin LA, et al. Antiemetic therapy: A review of recent studies and a report of a random assignment trial comparing metoclopramide with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Cancer Treat Rep. 1984;68:163–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gorter R. Management of anorexia-cachexia associated with cancer and HIV infection. Oncology Suppl. 1991;5:13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Struwe M, Kaempfer SH, Geiger CJ, et al. Effect of dronabinol on nutritional status in HIV infection. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27(7–8):827–31. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beal JE, Olson RLL, Morales JO, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beal JE, Olson R, Lefkowitz L, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dronabinol for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated anorexia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14:7–14. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(97)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ungerleider JT, Andyrsiak T, Fairbanks L, Ellison GW, Myers LW. Delta-9-THC in the treatment of spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis. Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse. 1987;7(1):39–50. doi: 10.1300/j251v07n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brady CM, DasGupta R, Dalton C, Wiseman OJ, Berkley KJ, Fowler CJ. An open-label pilot study of cannabis-based extracts for bladder dysfunction in advanced multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10(4):425–33. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1063oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Killestein J, Hoogervorst EL, Reif M, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally administered cannabinoids in MS. Neurology. 2002;58:1404–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.9.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vaney C, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Jobin P, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of an orally administered cannabis extract in the treatment of spasticity in patients with multiple sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Mult Scler. 2004;10(4):417–24. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1048oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zajicek J, Fox P, Sanders H, et al. UK MS Research Group. Cannabinoids for treatment of spasticity and other symptoms related to multiple sclerosis (CAMS study): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;10(4):417–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Berman JS, Symonds C, Birch R. Efficacy of two cannabis based medicinal extracts for relief of central neuropathic pain from brachial plexus avulsion: results of a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2004;112(3):299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carroll CB, Bain PG, Teare L, et al. Cannabis for dyskinesia in Parkinson disease: a randomized double-blind crossover study. Neurology. 2004;63(7):1245–50. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140288.48796.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carlini EA. The good and the bad effects of (−) trans-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Delta 9-THC) on humans. Toxicon. 2004;44(4):461–7. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Croxford JL. Therapeutic potential of cannabinoids in CNS disease. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(3):179–202. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iversen L. Cannabis and the brain. Brain. 2003;126:1252–70. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]