Abstract

Fibrosis is an important component of large conduit artery disease in hypertension. The endogenous tetrapeptide N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SDKP) has anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects in the heart and kidney. However, it is not known whether Ac-SDKP has an anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effect on conduit arteries such as the aorta. We hypothesize that in ANG II-induced hypertension Ac-SDKP prevents aortic fibrosis and that this effect is associated with decreased protein kinase C (PKC) activation, leading to reduced oxidative stress and inflammation and a decrease in the profibrotic cytokine transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and phosphorylation of its second messenger Smad2. To test this hypothesis we used rats with ANG II-induced hypertension and treated them with either vehicle or Ac-SDKP. In this hypertensive model we found an increased collagen deposition and collagen type I and III mRNA expression in the aorta. These changes were associated with increased PKC activation, oxidative stress, intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 mRNA expression, and macrophage infiltration. TGF-β1 expression and Smad2 phosphorylation also increased. Ac-SDKP prevented these effects without decreasing blood pressure or aortic hypertrophy. Ac-SDKP also enhanced expression of inhibitory Smad7. These data indicate that in ANG II-induced hypertension Ac-SDKP has an aortic antifibrotic effect. This effect may be due in part to inhibition of PKC activation, which in turn could reduce oxidative stress, ICAM-1 expression, and macrophage infiltration. Part of the effect of Ac-SDKP could also be due to reduced expression of the profibrotic cytokine TGF-β1 and inhibition of Smad2 phosphorylation.

Keywords: arteriosclerosis, vascular hypertrophy, inflammation, protein kinase C, transforming growth factor-β1/Smad

hypertension is associated with large conduit artery hypertrophy and an increase in extracellular matrix (ECM) content, especially collagen. Fibrosis is a major component of hypertensive vascular disease, causing vascular stiffness and arteriosclerosis (20, 37). Angiotensin II (ANG II) contributes to vascular injury by inducing inflammation, oxidative stress, excessive deposition of ECM, and hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (10). ANG II via its type 1 (AT1) receptor initiates activation of intracellular signaling cascades, including protein kinase C (PKC) activation. PKC-dependent activation of NAD(P)H oxidase leads to increased oxidative stress and inflammation, which play essential roles in vascular disease (1, 10, 19, 36). ANG II also induces vascular fibrosis by stimulating transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), which mediates its profibrotic effects by activating receptor-associated Smads (R-Smads, including Smad2 and Smad3) (35). Inhibitory Smads (I-Smads, i.e., Smad6 and Smad7) block TGF-β signaling by binding to TGF-β receptor type 1 receptors or by competing with activated R-Smad for binding to Smad4 (48).

N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SDKP) is an endogenous tetrapeptide originally described as a natural inhibitor of pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell proliferation (29). In vitro Ac-SDKP prevents collagen synthesis, cell proliferation, and TGF-β1-stimulated Smad2 phosphorylation in cardiac fibroblasts (42, 46). Ac-SDKP appears to act via a receptor that we have recently characterized (62) but not yet cloned. Furthermore, chronic blockade of endogenous Ac-SDKP with a specific prolyl oligopeptidase inhibitor promotes collagen accumulation (7).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors prevent degradation of endogenous Ac-SDKP, raising its circulating concentrations approximately fivefold (2, 3, 23). In ANG II-induced hypertension Ac-SDKP mediates anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects of ACE inhibitors (41). In hypertensive rats, long-term treatment with Ac-SDKP decreases inflammatory cell infiltration as well as cardiac and renal fibrosis (40, 41, 47). Furthermore, in rats with ANG II-induced hypertension Ac-SDKP also decreases the number of TGF-β-positive cells and Smad2 activation in the heart (41). Although the anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects of Ac-SDKP are well documented in the heart and kidney, it is not known whether Ac-SDKP has similar effects on conduit arteries such as the aorta. Thus we hypothesize that in ANG II-induced hypertension Ac-SDKP prevents aortic fibrosis. We also hypothesize that this effect is associated with decreased PKC activation, leading to reduced oxidative stress and inflammation and a decrease in the profibrotic cytokine TGF-β1 and phosphorylation of its second messenger Smad2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental groups.

This protocol was approved by the Henry Ford Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250–300 g (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were housed under controlled conditions and randomly divided into four groups: 1) vehicle; 2) Ac-SDKP (800 μg·kg−1·day−1); 3) ANG II (750 μg·kg−1·day−1); and 4) ANG II + Ac-SDKP. Ac-SDKP and ANG II were dissolved in 0.01 N acetic acid in saline. The dose of ANG II and Ac-SDKP was selected based on previous studies (21, 28, 40, 45). All treatments were carried out for 7 days by subcutaneous implantation of miniosmotic pumps (Alzet 2ML1). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was measured by tail cuff (IITC/Life Science) on day 0 (basal) and then at 3 and 6 days after miniosmotic pump implantation.

Morphological analysis.

After 7 days of treatment, rats were anesthetized with 50 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium. For histological studies the aortas were perfused via the left ventricle with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 5 min, followed by 10% buffered formalin for 5 min under pressure (150 mmHg). A 6-mm ring from the thoracic aorta obtained halfway between the left subclavian artery and the diaphragm was embedded in paraffin and cut into 6-μm sections. Extreme care was used to ensure that the aorta was not stretched on dissection. Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and photographed at ×40. Briefly, cross-sectional area and radial thickness of the media were measured with Sigma Scan Pro 5.0 software (Jandel Scientific) by an investigator unaware of the group assignment (32).

Collagen and elastin deposition.

To quantify collagen density, 6-μm sections were stained with a modified picrosirius red method (41). Elastin deposition was determined by staining with Verhoeff Van Giesson (56). Images were obtained under light microscopy (×200) and quantified with a computerized image analysis system (Microsuite Biological Imaging software, Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) by an investigator unaware of the groups. Collagen and elastin deposition were expressed as percentage of positively stained area to medial area.

Immunohistochemistry for lipid oxidation (4-hydroxy-2-nonenal) and macrophage infiltration.

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (33). Briefly, paraffin-embedded sections were incubated with primary antibodies against 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE, 1:200, OXIS), nitrotyrosine (1:50, Millipore), or ED-1 (a marker for macrophages; 1:500, Chemicon) overnight at 4°C. Immunoreactivity was detected with a Vectastain Elite ABC peroxidase kit (Vector Labs) and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole solution (AEC, Zymed Labs). A reddish-brown color was considered a positive stain. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were captured at ×400 magnification with an inverted microscope (1X81, Olympus America) and a digital camera (DP70, Olympus America). Quantitative analysis was performed by an investigator unaware of the groups. 4-HNE and nitrotyrosine quantification was assessed by measuring the positively stained area and expressed as a percentage of the medial plus intimal area. Macrophage infiltration was expressed as the number of macrophages per square millimeter of medial plus intimal area (adventitia not included because it did not remain intact).

Gene expression of collagen type I, collagen type III, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and 18S.

Another group of rats on each treatment (n = 6) was used for these studies, since formalin-fixed tissues cannot be used for assessing gene and protein expression. The thoracic aorta was immediately excised, rinsed briefly with PBS precooled at 4°C, dissected from adherent fat and connective tissues, and then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Frozen aortic tissue was homogenized with mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated with a RNeasy Fibrous Tissue minikit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed with an Omniscript Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). Semiquantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with the following specific primers: collagen type I: forward 5′-TCACCTACAGCACGCTTG-3′, reverse 5′-GGTCTGTTTCCAGGGTTG-3′ (245 bp); collagen type III: forward 5′-ATATCAAACACGCAAGGC-3′, reverse 5′-GATTAAAGCAAGAGGAACAC-3′ (175 bp); intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1: forward 5′-AGAAGGACTGCTTGGGGAA-3′, reverse 5′-CCTCTGGCGGTAATAGGTG-3′ (332 bp); 18S rRNA: forward 5′-AGGAATTGACGGAAGGGCAC-3′, reverse 5′-GTGCAGCCCCGGACATCTAAG-3′ (327 bp). 18S was used as internal control. The 28-cycle PCR program consisted of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 58°C, and 40 s of extension at 72°C. The PCR products were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining. Results are expressed as arbitrary densitometric units relative to 18S.

Western blot for phosphorylated PKC, TGF-β1, phosphorylated Smad2, and Smad7.

Aortic protein was extracted from frozen tissue (51) and concentration was determined with a Micro BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). Aliquots were separated by electrophoresis under nonreducing conditions, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with specific antibodies to phosphorylated (p-)PKC-α/βII (1:1,000, Cell Signal Technology), TGF-β1 (1:1,000, MAB240, R&D Systems), p-Smad2 (1:250, Cell Signal Technology), and Smad7 (1:250, Santa Cruz). Signals were revealed with chemiluminescence (ECL kit, Amersham Pharmacia) and visualized by autoradiography. Membranes were then stripped (Pierce) and reprobed with β-actin (1:1,000, Santa Cruz) or total Smad2 (T-Smad2, 1:500, Cell Signal Technology) to verify equal loading. Optical band density was quantified and expressed as arbitrary units relative to corresponding β-actin or T-Smad2. The molecular masses of positive bands were p-PKC-α/βII, 80 and 82 kDa; TGF-β1, 25 kDa; p-Smad2 and T-Smad2, 60 kDa; and Smad7, 51 kDa.

Statistical analysis.

All values are expressed as mean ± SE, with n indicating the number of animals in each group. For all parameters, Student's two-sample t-test was used to compare differences between groups, such as control vs. ANG II or ANG II vs. ANG II + Ac-SDKP. Hochberg's method of adjusting the α-level was used to control the possibility of making an incorrect decision across multiple tests. The type I error rate was set as α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Systolic blood pressure.

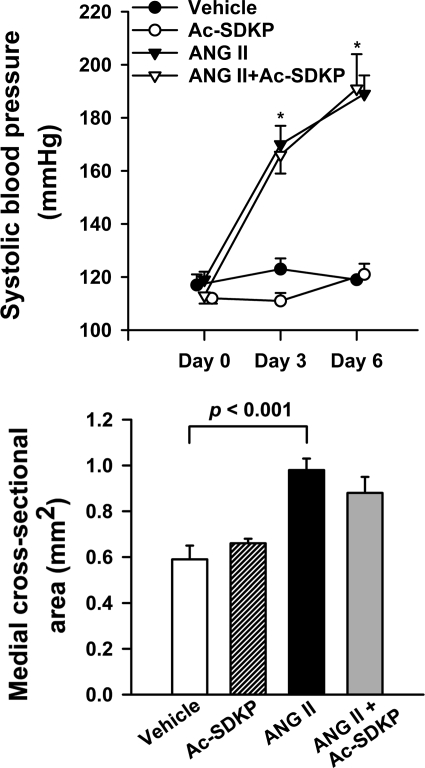

Baseline SBP was similar in all groups. At days 3 and 6, SBP increased significantly (P < 0.0001) in rats receiving ANG II compared with vehicle. There was no significant difference in SBP between ANG II and ANG II plus Ac-SDKP, indicating that Ac-SDKP did not alter ANG II-induced hypertension (Fig. 1, top).

Fig. 1.

Effect of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SDKP) on angiotensin II (ANG II)-induced hypertension and aortic hypertrophy. Rats were treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, ANG II, or ANG II + Ac-SDKP. Top: systolic blood pressure (n = 9 or 10/group). Bottom: aortic medial cross-sectional area (n = 5/group). Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.0001, vehicle vs. ANG II.

Morphological analysis.

ANG II significantly increased medial cross-sectional area (Fig. 1, bottom) and wall thickness of the thoracic aorta (vehicle 99.81 ± 7.37 vs. ANG II 157.71 ± 7.64 μm, P < 0.01). Ac-SDKP had no significant effect on arterial wall morphology.

Collagen and elastin deposition and collagen mRNA expression.

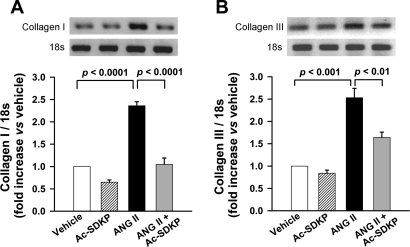

Picrosirius red staining was performed to assess collagen deposition in the aortic wall. As illustrated in Fig. 2, in ANG II-induced hypertension collagen deposition in the aorta media was significantly increased (P < 0.001, vehicle vs. ANG II). Ac-SDKP prevented these increases (P < 0.001, ANG II vs. ANG II + Ac-SDKP). Similarly, semiquantitative PCR analysis showed that ANG II significantly increased collagen type I and III mRNA expression, which was inhibited by Ac-SDKP (Fig. 3). Verhoeff Van Giesson staining of the aorta revealed increased elastin deposition within the media of ANG II-infused rats (P < 0.001, vehicle vs. ANG II). As shown in Fig. 4, this increase was blocked by coadministration of Ac-SDKP (P < 0.001, ANG II vs. ANG II + Ac-SDKP). Ac-SDKP alone had no effect on elastin density. The ratio of aortic elastin to collagen density (E/C) had a tendency to decrease in the ANG II group and increase in the ANG II plus Ac-SDKP group; however, these differences were not statistically significant (vehicle 2.10 ± 0.31, ANG II 1.78 ± 0.23, and ANG II + Ac-SDKP 2.19 ± 0.40).

Fig. 2.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on ANG II-induced collagen deposition in the aortic media. Top: representative images showing collagen deposition (red) stained with picrosirius red in aortas from rats treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, ANG II, or ANG II + Ac-SDKP. Magnification ×200. Bottom: collagen deposition in the aortic media was quantified with Olympus Microsuite Biological imaging software; positively stained area is expressed as % of the medial area. n = 5–8/group.

Fig. 3.

mRNA expression of collagen type I and III in rat aorta by semiquantitative PCR. Rats were treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, ANG II, or ANG II + Ac-SDKP. A: collagen type I mRNA expression. B: collagen type III mRNA expression. Bar graphs show mRNA expression of collagen type I or III indicated as the density ratio of collagen I or III to 18S. Data are means ± SE; n = 6 rats/group.

Fig. 4.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on ANG II-induced elastin deposition in the aortic media. Top: representative images showing elastic fibers (purple) stained with Verhoeff van Giesson in aortas from rats treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, ANG II, or ANG II + Ac-SDKP. Magnification ×200. Bottom: quantitative evaluation of elastin density in the aortic media. The stained area is indicated as % of the medial area. n = 8 or 9/group.

PKC phosphorylation.

ANG II significantly increased PKC phosphorylation (P < 0.05, vehicle vs. ANG II); Ac-SDKP prevented such increase (P < 0.05, ANG II vs. ANG II + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Western blot for protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylation in aortas. Rats were treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, ANG II, or ANG II + Ac-SDKP. The bands of phosphorylated (p-)PKC and β-actin were measured by densitometric analysis, and the quantitative data are indicated as the ratio of p-PKC to β-actin. Data are means ± SE; n = 5 or 6 rats/group.

In situ reactive oxygen species detection.

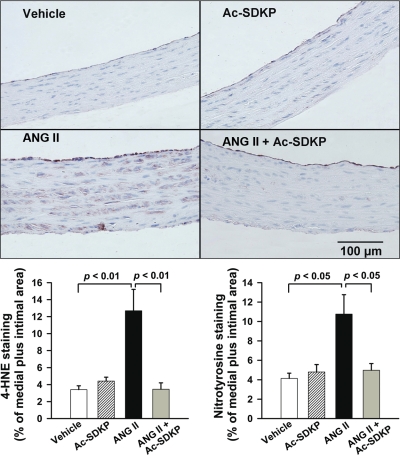

As expected, ANG II-induced hypertension caused a significant increase in oxidative stress as indicated by the immunohistochemical staining for 4-HNE. Staining was present across the media in the ANG II group (P < 0.01, vehicle vs. ANG II) (Fig. 6A). Similarly, staining for nitrotyrosine (a marker of peroxynitrite) was also significantly increased in the ANG II group (vehicle vs. ANG II, P < 0.05) (Fig. 6B). The increase in these oxidative stress markers was prevented by Ac-SDKP (Fig. 6). These data indicate that Ac-SDKP had an inhibitory effect on ANG II-induced oxidative stress.

Fig. 6.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on ANG II-induced oxidative stress in the aorta, as indicated by staining for 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE; a marker for lipid peroxidation) and nitrotyrosine (a marker for peroxynitrite). Top: representative images showing 4-HNE staining (brown) in aortas from rats treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, ANG II, or ANG II + Ac-SDKP. Magnification ×400. Bottom: quantification graphs for 4-HNE (left) and nitrotyrosine (right) staining. The positively stained area is expressed as % of the medial + intimal area. Values are means ± SE; n = 7 or 8/group (4-HNE) or 8 or 9/group (nitrotyrosine).

Macrophage infiltration and ICAM-1 mRNA expression.

The infiltrating macrophages were measured with ED-1 (a marker for macrophages) immunohistochemical staining and ICAM-1 mRNA expression with semiquantitative PCR. ED-1-positive cells in the aortic wall stained reddish-brown. Specificity of this immunostaining was confirmed by a negative staining in the absence of primary antibody in serial sections. Quantitative cell count analysis showed that ANG II significantly increased the number of ED-1-positive cells in the aortic wall (P < 0.01, vehicle vs. ANG II) and Ac-SDKP attenuated this effect (P < 0.05, ANG II vs. ANG II + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 7). Semiquantitative PCR showed that ANG II produced a twofold increase in aortic ICAM-1 mRNA expression, which was significantly prevented by Ac-SDKP treatment (P < 0.05, ANG II vs. ANG II + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on ANG II-induced macrophage infiltration in the aorta. Top: representative cross sections of aortas from rats treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, ANG II, or ANG II + Ac-SDKP. ED-1-positive cells (stained reddish-brown) are indicated by arrows. Magnification ×400. Bottom: quantitative analysis of macrophage infiltration, represented by the number of ED-1-positive cells per mm2 of intimal + medial area. n = 5/group.

Fig. 8.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on ANG II-induced aortic intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 mRNA expression. Rats were treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, ANG II, or ANG II + Ac-SDKP. Top: representative bands for ICAM-1 and 18S by semiquantitative PCR. Bottom: expression of ICAM-1 in the aorta, expressed as the density ratio of ICAM-1 to 18S. Data are means ± SE; n = 6/group.

TGF-β1/Smad signaling.

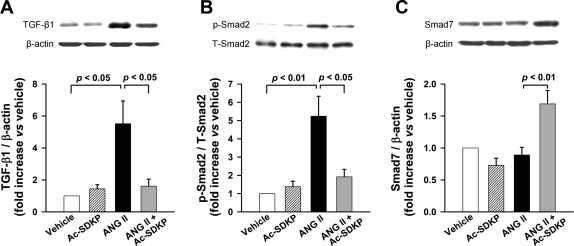

TGF-β1 expression increased significantly with ANG II administration (P < 0.05, vehicle vs. ANG II). This increase was significantly prevented by Ac-SDKP (P < 0.05, ANG II vs. ANG II + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 9A). ANG II induced a 5.2-fold increase in Smad2 phosphorylation compared with vehicle (P < 0.01), and Ac-SDKP significantly prevented this increase (P < 0.05, ANG II vs. ANG II + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 9B). I-Smad7 did not change in ANG II-treated rats compared with vehicle, whereas treatment with both ANG II and Ac-SDKP resulted in increased aortic I-Smad7 expression (P < 0.01, ANG II vs. ANG II + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 9.

TGF-β1 and Smad2 and -7 expression in the aortas of rats treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, ANG II, or ANG II + Ac-SDKP. Top: representative immunoblots. Bottom: quantification graphs. A: TGF-β1 expression. B: Smad2 phosphorylation. T-Smad2, total Smad2. C: Smad7 expression. Values are means ± SE; n = 5 or 6/group.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies from our group (40, 41, 47) have found that Ac-SDKP decreases cardiac and renal inflammation and fibrosis in various models of hypertension and in heart failure after myocardial infarction. We have now found that in the aorta of rats with ANG II-induced hypertension Ac-SDKP prevented increases in 1) collagen and elastin deposition and collagen type I and type III mRNA expression, 2) PKC activation, 3) oxidative stress, 4) ICAM-1 mRNA expression and macrophage infiltration, and 5) TGF-β1 expression and Smad2 activation, but it enhanced I-Smad7 expression. The present study provides the first in vivo evidence that Ac-SDKP plays an important role in preventing ANG II-induced aortic fibrosis. This protective effect may be mediated via inhibition of PKC activation that causes a decrease in oxidative stress, aortic inflammation, and activation of the TGF-β1/Smad2 pathway.

Fibrosis in the large-capacitance arteries occurs in hypertension and with aging, and it may contribute to the development of arteriosclerosis and isolated systolic hypertension (9, 22). We evaluated aortic collagen deposition with a histomorphometric approach that closely approximates hydroxyproline concentrations within tissue (4). Consistent with previous reports (6, 58), we found that ANG II increased aortic collagen deposition, associated with marked upregulation of collagen type I and III mRNA expression. The effects of Ac-SDKP occurred without significant changes in blood pressure or aortic hypertrophy (indicated by aortic wall thickness and medial cross-sectional area). In parallel with this, we previously reported (40, 41, 45, 47, 61) that Ac-SDKP, despite decreasing cardiac inflammation and fibrosis, changed neither blood pressure nor left ventricular hypertrophy.

Elastin is a vessel wall component with a low elastic modulus (5 × 106 dyn/cm3) that contributes to aortic distensibility (11). Contradictory results have been reported concerning elastin density in the aorta of hypertensive animals, but such discrepancies may be explained by differences in the models studied. Elastin was reportedly increased in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) (4) and in ANG II-induced hypertension (11, 30). On the other hand, elastin was reportedly decreased in rats with renovascular hypertension, which is a model of high renin (55). In the present study, we observed that in ANG II-induced hypertension elastin levels increased and Ac-SDKP prevented this increase. In agreement with our findings, it has been reported that the ACE inhibitor enalapril (increases plasma Ac-SDKP concentrations) prevented elastin accumulation in young Wistar rats (26). Since elastin provides vascular elasticity while collagen provides tensile strength (11), the ratio of aortic elastin to collagen density (E/C) has been proposed to predict corresponding changes in vessel stiffness in vivo. In the present study, the E/C had a tendency to decrease in the ANG II group and increase in the ANG II plus Ac-SDKP group; however, these differences are not statistically significant. The E/C were reportedly decreased in SHR (31) and renovascular hypertension (55) and were normalized by ACE inhibition (which increases Ac-SDKP). However, it must be noted that the hypertension and the treatment were more chronic (months) than in our study (1 wk). Also, the decrease in E/C is not a uniform finding (5, 11, 25).

We also investigated whether Ac-SDKP decreases PKC-α/β phosphorylation in ANG II-induced hypertension. PKC has been implicated in NADPH activation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in ANG II models of hypertension (15, 17, 50). PKC-α selectively regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced macrophage activation, and PKC-β participates in differentiation of monocytes to macrophages (49, 53). Furthermore, we showed previously (52) that in vitro Ac-SDKP decreases the transformation of monocytes to macrophages and also inhibits macrophage activation. In VSMCs and mesangial cells, PKC has also been implicated in induction of TGF-β1 gene expression and activity in response to ANG II (12, 59). PKC-β inhibition attenuates macrophage infiltration, interstitial fibrosis, TGF-β1 expression, and Smad2 phosphorylation in kidneys of diabetic rats (27). In the present study, we found that ANG II induced a significant increase in PKC-α/βII phosphorylation, and Ac-SDKP prevented this increase. Thus it is possible that enhanced aortic PKC activation contributes to ANG II-induced oxidative stress, macrophage infiltration, and activation of the TGF-β1/Smad2 pathway, which in turn stimulates collagen production.

Evidence supports the association between oxidative stress and fibrosis. ROS may stimulate ECM deposition (collagen and elastin) by increasing proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β1 that, via the Smad system, induce collagen synthesis (43). In the present model of ANG II-induced hypertension, we explored whether Ac-SDKP affects arterial oxidative stress. Consistent with other reports (8, 44, 57), we found that ANG II induced an increase in oxidative stress in the aorta as evidenced by increased 4-HNE (a product of lipid oxidation by H2O2, OONO−, and OH−) and nitrotyrosine expression, and that Ac-SDKP prevented these increases. It is also known that hypertension can induce oxidative stress through its effect on vessel wall stretching (18); however, in the present study Ac-SDKP did not lower blood pressure in ANG II-induced hypertension. Thus it could be proposed that the inhibitory effect of Ac-SDKP on arterial oxidative stress is independent of changes in blood pressure.

Although we previously reported that Ac-SDKP inhibited macrophage infiltration in the heart and in the kidney, it is not certain whether the same effect will occur in the aorta (39, 41, 45, 61). Indeed, it has been recognized that macrophages isolated from different anatomic sites display a diversity of phenotypes and capabilities. Because macrophage function is dependent in part on signals received from the immediate microenvironment (tissues), it is suggested that macrophage heterogeneity may arise from unique conditions within specific tissues (13, 14, 54). Studies have suggested a proinflammatory role for ROS in the vasculature, including increased adhesion molecule expression, release of cytokines, and chemoattraction of leukocytes to the aorta at sites of endothelial damage (16, 34). Thus in the present study, we measured ICAM mRNA expression and macrophage infiltration as indicators of inflammation. Consistent with previous reports that Ac-SDKP decreases cardiac and renal inflammatory cell infiltration in hypertensive rats (40, 41, 47), here we found that in the aorta of rats with ANG II-induced hypertension Ac-SDKP significantly prevented both ICAM-1 mRNA expression and the increase in ED-1-positive cells (macrophages) in the aorta. Macrophages have been identified as a major source of the profibrotic growth factor TGF-β1 (60). Taken together with our data regarding oxidative stress, the present study suggests that Ac-SDKP may attenuate ANG II-induced aortic fibrosis, partially by inhibiting oxidative stress, macrophage infiltration, and TGF-β1 expression.

TGF-β1 is an important ECM regulator in the cardiovascular system. In VSMCs and fibroblasts, TGF-β1 increases synthesis of ECM proteins such as fibronectin and collagens. Also, TGF-β1 mediates ANG II-induced vascular fibrosis via activation of R-Smads (including Smad2 and Smad3), which are counterregulated by I-Smads (Smad6 and Smad7) (48). Therefore, in the present study we focused on the TGF-β1/Smad pathway to address possible mechanisms by which Ac-SDKP prevents ANG II-induced aortic fibrosis. Consistent with our previous reports that Ac-SDKP administration in hypertensive models decreases cardiac TGF-β expression and Smad2 activation (38, 41, 61), we found that Ac-SDKP significantly attenuated ANG II-induced aortic TGF-β1 expression and Smad2 phosphorylation. Interestingly, Ac-SDKP increased I-Smad7 expression in aortas of ANG II hypertensive rats, whereas Ac-SDKP or ANG II alone did not alter I-Smad7. It could be that I-Smad7 partially accounts for the inhibitory effect of Ac-SDKP on ANG II-induced Smad2 activation. In agreement with our findings, Kanasaki et al. (24) demonstrated that in human mesangial cells Ac-SDKP inhibits TGF-β signal transduction through suppression of R-Smad activation via nuclear export of I-Smad7. However, in contrast to our present findings in the vasculature, we previously reported (41) that Ac-SDKP did not affect I-Smad7 expression in the heart after 4 wk of ANG II infusion, possibly because of low cardiac expression of I-Smad7.

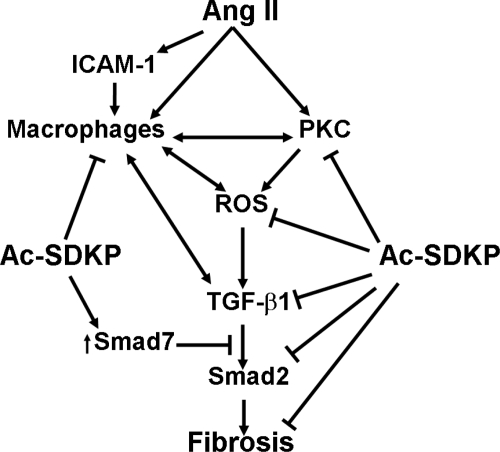

Taken together, our data indicate that Ac-SDKP has an antifibrotic effect on the aorta of ANG II hypertensive rats. This effect may be mediated by inhibiting aortic PKC activation, causing a decrease in oxidative stress, inflammation, and the TGF-β1/Smad2 pathway (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Hypothesized mechanism by which Ac-SDKP inhibits aortic fibrosis in ANG II-induced hypertension. As illustrated, ANG II activates PKC and also induces ICAM-1 expression and macrophage activation. PKC activates macrophages and also NADPH, both of which can increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Macrophages and ROS induce expression of TGF-β1, which, via receptor-associated Smads (Smad2 and -3), induces fibrosis. Ac-SDKP acts by decreasing PKC activation, ROS generation, macrophage infiltration, TGF-β1 expression, and inhibition of Smad2 phosphorylation. Ac-SDKP increases inhibitory Smad7, which blocks the effects of TGF-β1. Ac-SDKP may also directly inhibit fibrosis by blocking collagen synthesis and fibroblast proliferation (46).

Perspectives

Increased ECM deposition is an important feature of target organ damage in hypertension. In the present study, we found that Ac-SDKP attenuates aortic fibrosis in ANG II-induced hypertension, possibly by preventing PKC activation, oxidative stress, inflammation, and TGF-β1/Smad2 activation. These findings will help us understand some of the mechanisms by which vascular fibrosis develops in hypertension and arteriosclerosis and also in aging subjects. Design of nonpeptidic analogs of Ac-SDKP would be useful for treating fibrosis in large vessels.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-28982 (O. A. Carretero) and HL-071806 (N.-E. Rhaleb).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander RW Theodore Cooper Memorial Lecture. Hypertension and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Oxidative stress and the mediation of arterial inflammatory response: a new perspective. Hypertension 25: 155–161, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azizi M, Ezan E, Nicolet L, Grognet JM, Menard J. High plasma level of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline: a new marker of chronic angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Hypertension 30: 1015–1019, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azizi M, Rousseau A, Ezan E, Guyene TT, Michelet S, Grognet JM, Lenfant M, Corvol P, Ménard J. Acute angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition increases the plasma level of the natural stem cell regulator N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline. J Clin Invest 97: 839–844, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benetos A, Levy BI, Lacolley P, Taillard F, Duriez M, Safar ME. Role of angiotensin II and bradykinin on aortic collagen following converting enzyme inhibition in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 3196–3201, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bezie Y, Lamaziere JM, Laurent S, Challande P, Cunha RS, Bonnet J, Lacolley P. Fibronectin expression and aortic wall elastic modulus in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18: 1027–1034, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brassard P, Amiri F, Schiffrin EL. Combined angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptor blockade on vascular remodeling and matrix metalloproteinases in resistance arteries. Hypertension 46: 598–606, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavasin MA, Liao TD, Yang XP, Yang JJ, Carretero OA. Decreased endogenous levels of Ac-SDKP promote organ fibrosis. Hypertension 50: 130–136, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cifuentes ME, Rey FE, Carretero OA, Pagano PJ. Upregulation of p67phox and gp91phox in aortas from angiotensin II-infused mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H2234–H2240, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dao HH, Essalihi R, Bouvet C, Moreau P. Evolution and modulation of age-related medial elastocalcinosis: impact on large artery stiffness and isolated systolic hypertension. Cardiovasc Res 66: 307–317, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Ciuceis C, Amiri F, Brassard P, Endemann DH, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reduced vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries of angiotensin II-infused macrophage colony-stimulating factor-deficient mice. Evidence for a role in inflammation in angiotensin-induced vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 2106–2113, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitch RM, Rutledge JC, Wang YX, Powers AF, Tseng JL, Clary T, Rubanyi GM. Synergistic effect of angiotensin II and nitric oxide synthase inhibitor in increasing aortic stiffness in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1190–H1198, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbons GH, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy vs. hyperplasia: autocrine transforming growth factor-β1 expression determines growth response to angiotensin II. J Clin Invest 90: 456–461, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon S Macrophage heterogeneity and tissue lipids. J Clin Invest 117: 89–93, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 953–964, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griendling KK, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 74: 1141–1148, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grisham MB, Granger DN, Lefer DJ. Modulation of leukocyte-endothelial interactions by reactive metabolites of oxygen and nitrogen: relevance to ischemic heart disease. Free Radic Biol Med 25: 404–433, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heitzer T, Wenzel U, Hink U, Krollner D, Skatchkov M, Stahl RAK, Macharzina R, Bräsen JH, Meinertz T, Münzel T. Increased NAD(P)H oxidase-mediated superoxide production in renovascular hypertension: evidence for an involvement of protein kinase C. Kidney Int 56: 252–260, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard AB, Alexander RW, Nerem RM, Griendling KK, Taylor WR. Cyclic strain induces an oxidative stress in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 272: C421–C427, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoguchi T, Nawata H. NAD(P)H oxidase activation: a potential target mechanism for diabetic vascular complications, progressive β-cell dysfunction and metabolic syndrome. Curr Drug Targets 6: 495–501, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Intengan HD, Schiffrin EL. Vascular remodeling in hypertension. Roles of apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Hypertension 38: 581–587, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwamoto T, Kita S, Zhang J, Blaustein MP, Arai Y, Yoshida S, Wakimoto K, Komuro I, Katsuragi T. Salt-sensitive hypertension is triggered by Ca2+ entry via Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type-1 in vascular smooth muscle. Nat Med 10: 1193–1199, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izzo JL, Levy D, Black HR. Clinical Advisory Statement. Importance of systolic blood pressure in older Americans. Hypertension 35: 1021–1024, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Junot C, Gonzales MF, Ezan E, Cotton J, Vazeux G, Michaud A, Azizi M, Vassiliou S, Yiotakis A, Corvol P, Dive V. RPX 407, a selective inhibitor of the N-domain of angiotensin I-converting enzyme, blocks in vivo the degradation of hemoregulatory peptide acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro with no effect on angiotensin I hydrolysis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297: 606–611, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanasaki K, Koya D, Sugimoto T, Isono M, Kashiwagi A, Haneda M. N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline inhibits TGF-β-mediated plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression via inhibition of Smad pathway in human mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 863–872, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karam H, Heudes D, Hess P, Gonzales MF, Löffler BM, Clozel M, Clozel JP. Respective role of humoral factors and blood pressure in cardiac remodeling of DOCA hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc Res 31: 287–295, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keeley FW, Elmoselhi A, Leenen FHH. Enalapril suppresses normal accumulation of elastin and collagen in cardiovascular tissues of growing rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H1013–H1021, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Hepper C, Gow RM, Jaworski K, Kemp BE, Wilkinson-Berka JL, Gilbert RE. Protein kinase C beta inhibition attenuates the progression of experimental diabetic nephropathy in the presence of continued hypertension. Diabetes 52: 512–518, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiarash A, Pagano PJ, Tayeh M, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA. Upregulated expression of rat heart intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in angiotensin II- but not phenylephrine-induced hypertension. Hypertension 37: 58–65, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenfant M, Wdzieczak-Bakala J, Guittet E, Prome JC, Sotty D, Frindel E. Inhibitor of hematopoietic pluripotent stem cell proliferation: purification and determination of its structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 779–782, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy BI, Benessiano J, Henrion D, Caputo L, Heymes C, Duriez M, Poitevin P, Samuel JL. Chronic blockade of AT2-subtype receptors prevents the effect of angiotensin II on the rat vascular structure. J Clin Invest 98: 418–425, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy BI, Michel JB, Salzmann JL, Azizi M, Poitevin P, Camilleri JP, Safar ME. Arterial effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in renovascular and spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens Suppl 6: S23–S25, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, Ormsby A, Oja-Tebbe N, Pagano PJ. Gene transfer of NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor to the vascular adventitia attenuates medial smooth muscle hypertrophy. Circ Res 95: 587–594, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Yang F, Yang XP, Jankowski M, Pagano PJ. NAD(P)H oxidase mediates angiotensin II-mediated vascular macrophage infiltration and medial hypertrophy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 776–782, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marui N, Offermann MK, Swerlick R, Kunsch C, Rosen CA, Ahmad M, Alexander RW, Medford RM. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) gene transcription and expression are regulated through an antioxidant-sensitive mechanism in human vascular endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 92: 1866–1874, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massague J TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 67: 753–791, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C82–C97, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ooshima A, Fuller GC, Cardinale GJ, Spector S, Udenfriend S. Increased collagen synthesis in blood vessels of hypertensive rats and its reversal by antihypertensive agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 71: 3019–3023, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng H, Carretero OA, Brigstock DR, Oja-Tebbe N, Rhaleb NE. Ac-SDKP reverses cardiac fibrosis in rats with renovascular hypertension. Hypertension 42: 1164–1170, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng H, Carretero OA, Liao TD, Peterson EL, Rhaleb NE. Role of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline in the antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor captopril in hypertension. Hypertension 49: 695–703, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng H, Carretero OA, Raij L, Yang F, Kapke A, Rhaleb NE. Antifibrotic effects of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline on the heart and kidney in aldosterone-salt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 37: 794–800, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng H, Carretero OA, Vuljaj N, Liao TD, Motivala A, Peterson EL, Rhaleb NE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. A new mechanism of action. Circulation 112: 2436–2445, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pokharel S, Rasoul S, Roks AJM, van Leeuwen REW, van Luyn MJA, Deelman LE, Smits JF, Carretero OA, van Gilst WH, Pinto YM. N-acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro inhibits phosphorylation of Smad2 in cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 40: 155–161, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poli G, Parola M. Oxidative damage and fibrogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med 22: 287–305, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajagopalan S, Kurz S, Münzel T, Tarpey M, Freeman BA, Griendling KK, Harrison DG. Angiotensin II-mediated hypertension in the rat increases vascular superoxide production via membrane NADH/NADPH oxidase activation. Contribution to alterations of vasomotor tone. J Clin Invest 97: 1916–1923, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasoul S, Carretero OA, Peng H, Cavasin MA, Zhuo J, Sanchez-Mendoza A, Brigstock DR, Rhaleb NE. Antifibrotic effect of Ac-SDKP and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in hypertension. J Hypertens 22: 593–603, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhaleb NE, Peng H, Harding P, Tayeh M, LaPointe MC, Carretero OA. Effect of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline on DNA and collagen synthesis in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 37: 827–832, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rhaleb NE, Peng H, Yang XP, Liu YH, Mehta D, Ezan E, Carretero OA. Long-term effect of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline on left ventricular collagen deposition in rats with 2-kidney, 1-clip hypertension. Circulation 103: 3136–3141, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruiz-Ortega M, Rodriguez-Vita J, Sanchez-Lopez E, Carvajal G, Egido J. TGF-β signaling in vascular fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res 74: 196–206, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schultz H, Engel K, Gaestel M. PMA-induced activation of the p42/44ERK- and p38RK-MAP kinase cascades in HL-60 cells is PKC dependent but not essential for differentiation to the macrophage-like phenotype. J Cell Physiol 173: 310–318, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seshiah PN, Weber DS, Rocic P, Valppu L, Taniyama Y, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II stimulation of NAD(P)H oxidase activity: upstream mediators. Circ Res 91: 406–413, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharifi AM, Schiffrin EL. Apoptosis in vasculature of spontaneously hypertensive rats: effect of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and a calcium channel antagonist. Am J Hypertens 11: 1108–1116, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma U, Rhaleb NE, Pokharel S, Harding P, Rasoul S, Peng H, Carretero OA. Novel anti-inflammatory mechanisms of N-acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro in hypertension-induced target organ damage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1226–H1232, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.St-Denis A, Chano F, Tremblay P, St-Pierre Y, Descoteaux A. Protein kinase C-α modulates lipopolysaccharide-induced functions in a murine macrophage cell line. J Biol Chem 273: 32787–32792, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stvrtinova V, Jakubovsky J, Hulin I. Inflammation and fever. In: Pathophysiology: Principles of Disease. Academic Electronic Press, 1995.

- 55.Veniant M, Gray GA, Heudes D, Menard J, Clozel JP. Structural changes and cyclic GMP content of the aorta after calcium antagonism or angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in renovascular hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 13: 731–737, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verhoeff FH Some new staining methods of wide applicability including a rapid differential stain for elastic tissue. JAMA 50: 876–877, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang HD, Johns DG, Xu S, Cohen RA. Role of superoxide anion in regulating pressor and vascular hypertrophic response to angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1697–H1702, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weisberg AD, Albornoz F, Griffin JP, Crandall DL, Elokdah H, Fogo AB, Vaughan DE, Brown NJ. Pharmacological inhibition and genetic deficiency of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 attenuates angiotensin II/salt-induced aortic remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 365–371, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weiss RH, Ramirez A. TGF-β- and angiotensin-II-induced mesangial matrix protein secretion is mediated by protein kinase C. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 2804–2813, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu LL, Cox A, Roe CJ, Dziadek M, Cooper ME, Gilbert RE. Transforming growth factor β1 and renal injury following subtotal nephrectomy in the rat: role of the renin-angiotensin system. Kidney Int 51: 1553–1567, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang F, Yang XP, Liu YH, Xu J, Cingolani O, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA. Ac-SDKP reverses inflammation and fibrosis in rats with heart failure after myocardial infarction. Hypertension 43: 229–236, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhuo JL, Carretero OA, Peng H, Li XC, Regoli D, Neugebauer W, Rhaleb NE. Characterization and localization of Ac-SDKP receptor binding sites using 125I-labeled Hpp-Aca-SDKP in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H984–H993, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]