Abstract

We tested the ability of healthy elderly persons to use anticipatory synergy adjustments (ASAs) prior to a self-triggered perturbation of one of the fingers during a multi-finger force production task. An index of a force-stabilizing synergy was computed reflecting co-variation of commands to fingers. The subjects produced constant force by pressing with the four fingers of the dominant hand on force sensors against constant upward directed forces. The middle finger could be unloaded either by the subject pressing the trigger or unexpectedly by the experimenter. In the former condition, the synergy index showed a drop (interpreted as ASA) prior to the time of unloading. This drop started later and was smaller in magnitude as compared to ASAs reported in an earlier study of younger subjects. At the new steady-state, a new sharing pattern of the force was reached. We conclude that aging is associated with a preserved ability to explore the flexibility of the mechanically redundant multi-finger system but a decreased ability to use feed-forward adjustments to self-triggered perturbations. These changes may contribute to the documented drop in manual dexterity with age.

Keywords: hand, force production, coordination, human

Introduction

Several recent papers described anticipatory synergy adjustments (ASAs) during multi-finger force production tasks (Kim et al. 2006; Olafsdottir et al. 2005; Olafsdottir et al. 2007; Shim et al. 2005). In those studies, synergies were defined as patterns of co-variation among finger forces or finger modes (hypothetical independent control signals to individual fingers that are manipulated by the controller (Danion et al. 2003), across repetitive trials that stabilized the total force (Latash et al. 2002; Shim et al. 2005; Scholz et al. 2002). In tasks, where the level of force had to be changed quickly in a predictable manner, a change in the index of finger force co-variation has been observed prior to the change in the total force (Kim et al. 2006; Olafsdottir et al. 2005; Shim et al. 2005). This phenomenon, ASA started approximately 100-150 ms prior to the earliest change in the total force. ASAs have been assumed to reflect a feed-forward control mechanism similar to anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs, Kim et al. 2006; Massion, 1992). APAs are seen as changes in the activity of postural muscles in preparation to an action that is associated with a perturbation to balance (Bouisset & Zattara, 1987).

Aging is associated with a variety of changes in the muscles, their motor unit composition, and neural control mechanisms (reviewed in Reeves et al. 2006). In particular, APAs have been reported to be reduced in magnitude and delayed in elderly (Woollacott & Manchester, 1993). A recent study documented similar age-related changes in ASAs prior to a fast action (Olafsdottir et al. 2007). However, that study did not involve any perturbation making comparisons with reports on APA changes with age difficult. The main purpose of the current study has been to investigate possible anticipatory changes of indices of finger coordination prior to a predictable perturbation in elderly individuals. We hypothesized that ASAs would be observed in elderly, but that they would be smaller and delayed as compared to ASAs reported in a recent study of young persons (Kim et al. 2006).

Methods

Thirteen elderly individuals volunteered to participate in the study (seven males and six females). Their average age, height and mass was 77 ± 4 years, 175.5 ± 6.6 cm and 84.8 ± 12.1 kg for the males and 77 ± 4 years, 160.4 ± 10.1 cm and 60.5 ± 7.8 kg respectively for the females. The subjects were recruited from a local retirement community and passed a screening process that involved a cognition test (mini-mental status exam ≥24 points), a depression test (Beck depression inventory ≤ 20 points), a quantitative sensory test (monofilaments ≤ 3.22) and a general neurological examination. All the subjects were right-handed according to their preferred hand use during eating and writing. We purposefully selected for the study elderly subjects who exercised regularly and were in a generally good physically shape (self-reported). All subjects gave informed consent according to the procedures approved by the Office for Research Protection of The Pennsylvania State University.

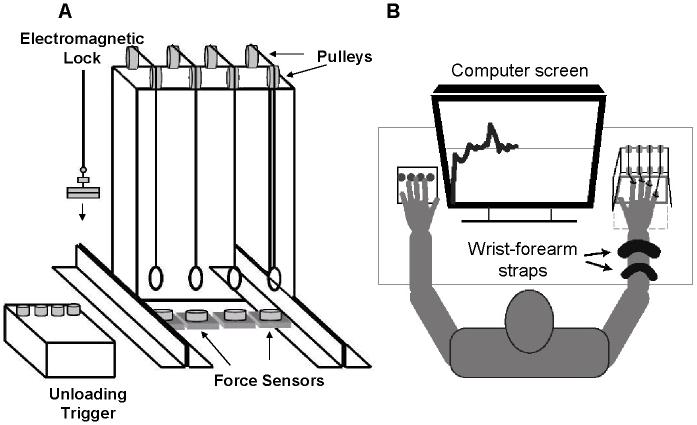

Four electromagnetic locks were suspended with plastic strings over an inverted U-shaped metal frame via a pulley system (Figure 1). The other end of each plastic string had a loop through which a finger could be inserted. Each electromagnetic lock had a load attached to it (200 g for males, 100 g for females); a load could be released by pressing a button on the trigger box. Four piezoelectric force sensors (Model 208A03, Piezotronic, Inc. Depew, NY, USA) were placed inside a metal frame and under the fingertips of the right hand. The four sensors were medio-laterally distributed 3 cm apart and could be adjusted in the forward-backward direction within 6 cm to fit individual subject’s hand anatomy. Once a comfortable position of the sensors had been found, double sided tape was used to keep them in place. The sensors measured the pressing force produced by the fingers. The plastic loops were positioned under the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers so that the loads caused vertical forces acting on each finger. As a result, the subjects had to produce a flexion force by each finger to touch the force sensors.

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of the experimental setup. A. The metal frame with the pulley system that the loads were suspended over. The force sensor positions were adjusted to fit the individual subject’s anatomy. The electromagnetic locks could be turned off by pressing a button, which released the load. The trigger box was located to the left of the subject in self-triggered trials and behind a screen during experimenter-triggered trials. B. The position of the subject and an example of its performance.

During the experiment, subjects sat on a chair facing the testing table with their right shoulder at about 45° of abduction and 45° of flexion, the elbow flexed approximately 45° and the wrist in neutral position. A dome shaped wooden piece was placed under the subject’s palm to help maintain a constant hand configuration. A 17” computer monitor, located about 80 cm away from the subject, displayed the task (see later) and the actual total force produced by all four fingers. A black cardboard divider was used to block both the loads and the trigger box from the subject’s view. During trials with self-triggered perturbations, the trigger box was placed to the left of the subjects and their left index finger was placed on the load releasing button. A LabVIEW-based program was used for data acquisition. The data were collected at 1000 Hz with a 12-bit resolution.

The experiment consisted of two series of trials, with self-triggered (SELF) and experimenter-triggered (EXP) perturbations of the middle finger. Before each trial, the subject was instructed to place the fingers on the force sensors but refrain from pressing down. The computer generated two “beeps” (get ready) and a cursor showing the total force produced by all four fingers started to move across the screen. The screen also showed a horizontal template line at the 8 N force level. Note that, although the task was set similarly for the males and females, the difference in the weight of the loads required the males to produce about 33% larger downward forces as compared to the females. This partly reflected the gender related difference in the maximal voluntary force (Shinohara et al. 2003; Olafsdottir et al. 2007). The subjects were asked to press on the force sensors with all four fingers and match the total force output to the horizontal line. Each trial lasted 10 s. During a 3-s interval, starting 3 s after the beginning of the trial, the middle finger (the task finger) was unloaded by pushing the corresponding load-release button, either unexpectedly by the experimenter or by the subject at a self-selected time. Unloading the finger caused its recorded level of force to increase. Subjects were asked to try to maintain the total force level at 8 N at all times and return to it as quickly as possible following a perturbation. Each subject performed 15 trials within each condition with 10 s intervals between trials and 3 min interval between the conditions. The order of conditions was balanced across the subjects and 4-7 practice trials were given prior to each condition.

The data were analyzed off-line using a MatLab-based software (MathWorks Inc. Natick, MA). The force data were filtered at 100 Hz using a 2-order, zero-lag low-pass Butterworth filter. When the trigger button was pushed, a rectangular electrical pulse was recorded. The data were aligned in time by the time of the ascending edge of the pulse, t0.

The average time profiles of the individual finger forces, Fi(t) (i = I, M, R, L) and of the total force, FTOT(t) were computed across trials within each condition for each subject. The average time profiles of the force of the middle finger (FM(t)) and the total force of other fingers (FIRL(t)) were computed. To compare the sharing of the total force between the M and IRL fingers before and after the perturbation, FM(t) and FIRL(t) and the total force, FTOT(t) were averaged across two 200 ms time intervals, from 700 ms to 500 ms prior to t0 and from 1500 to 1700 ms after t0. These time intervals were selected to reflect steady-states unaffected by the task initiation and the perturbation.

The variance of individual finger forces, VarFi(t), and the variance of the total force, VarFTOT(t), were computed across trials for each point in time. Further the sum of the variances of individual finger forces, ∑VarFi(t), was computed. Co-variation among finger forces was estimated using an index ΔV(t) = [∑VarFi(t) - VarFTOT(t)]/ ∑VarFi(t). Note that ΔV(t) > 0 corresponds to negative co-variation among finger forces, and the variance of the total force is lower than if the individual finger force deviations varied independently (Bienaymé theorem). Therefore, ΔV(t) > 0, can be interpreted as reflecting a synergy stabilizing the total force. To study deviations of ΔV from its steady-state level across subjects, we computed an index ΔΔV(t) that reflected changes in ΔV as compared to its value 200 ms prior to the time of perturbation (t0). The 200 ms time interval was selected based on earlier studies (Kim et al. 2006; Olafsdottir et al. 2007) that have shown no changes in the ΔV index earlier than 150 ms prior to an action or to a perturbation.

The data are presented in the text as means and standard errors of the mean. Mixed-effects two-way ANOVA with factors Task (two levels: SELF and EXP) and Time (two levels: before and after the perturbation) was used to quantify differences in the steady-state level of FM(t), FIRL(t) and FTOT(t) before and after t0. For statistical analysis of the time evolution of ΔΔV, the time interval from 200 ms before t0 until t0 was divided into eight 25 ms time intervals. ANOVA with repeated measures with factors Task (two levels: SELF and EXP) and Time (eight levels corresponding to time intervals from 200 ms before t0 until t0) was used. Multiple comparisons with Bonferroni corrections were used to further analyze the effects of the ANOVAs. Level of significance was set at p = 0.05.

Results

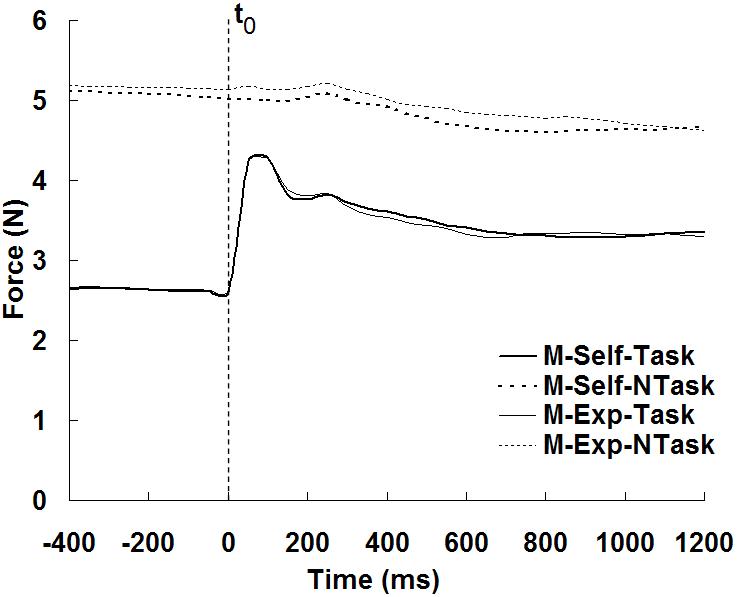

The unloading of the middle finger caused its pressing force to increase sharply. Following the force increase, an adjustment of all finger forces was observed until the prescribed force level was reached again. Figure 2 shows the time profiles of FM and FIRL in both SELF and EXP conditions, averaged across subjects. Prior to the unloading, the middle finger produced, on average, one-third of the total force in both conditions, SELF: 34.2 ± 1.8 %; EXP: 33.8 ± 2.4 %. Following the perturbation, the adjustment of finger forces caused a new sharing pattern at the new steady-state. M finger increased its contribution to about 40% (SELF: 42.3 ± 1.8 %; EXP: 40.1 ± 2.2 %) while the other fingers (IRL) decreased their force output. This effect was confirmed by a two-way ANOVA that showed significant effects of Time on both FM and FIRL (FM: F1,48 = 16.43, p < 0.001; FIRL: F1,48 = 5.94, p < 0.05) but no effect of Task (FM: p = 0.78; FIRL: p = 0.58). The total force, FTOT(t) was slightly larger after the perturbation than before in both conditions (SELF: 7.83 ± 0.03 N vs. 8.09 ± 0.12 N; EXP: 7.80 ± 0.03 N vs. 8.21 ± 0.13 N) but only in the experimenter-triggered condition did this difference reach significance (p< 0.01).

Figure 2.

Averaged across subjects time profiles of the forces produced by the middle finger (FM, solid traces) and other fingers (FIMR, dashed traces) in both self-(thick traces) and experimenter-triggered (thin traces) trials. All trials were aligned by the time of unloading, t0.

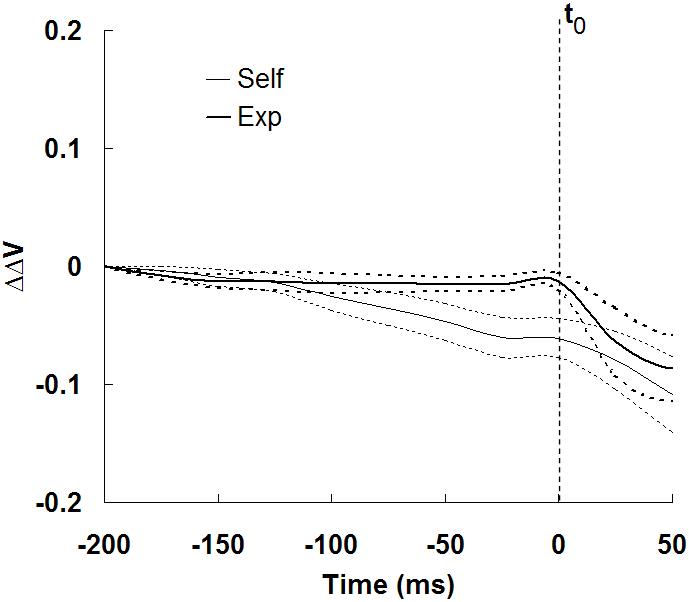

During the steady-state before the perturbation, the subjects showed predominantly negative co-variation among finger forces. This was reflected in positive values of ΔV, 0.89 ± 0.02 in SELF and 0.95 ± 0.01 in EXP. In the EXP condition, ΔV maintained its level until the time of perturbation (t0), whereas in the SELF condition, an early decrease in ΔV could be seen, starting approximately 50 to 100 ms prior to t0. Figure 3 shows the average change in ΔV (ΔΔV) over all subjects in both SELF and EXP conditions with standard errors. A repeated-measures ANOVA confirmed significant effects of Task (F1,12 = 6.182, p < 0.05), Time (F3.247,38.958 = 8.754, p < 0.001) and Task × Time interaction (F2.440,29.283 = 6.250, p <0.05). Multiple comparisons with Bonferroni corrections confirmed that ΔΔV in the SELF condition was significantly smaller than in the EXP condition over three time intervals, starting 75 ms before t0 until t0 (p < 0.05). In SELF condition ΔV dropped, on average, by 0.06 ± 0.01 by t0, while in EXP condition no change in ΔV was seen (on average, under 0.01).

Figure 3.

Time profile of changes (ΔΔV) in the index of finger force co-variation (ΔV) averaged across all subjects with standard errors. Thick solid and dashed lines show the average and standard error for the experimenter-triggered condition and thin solid and dashed lines show the corresponding data for the self-triggered condition. Time zero (t0) is the time of the middle finger unloading.

Discussion

The main finding of the experiment is that, when a finger force was perturbed by the subjects themselves (SELF), they were able to modify the pattern of finger force co-variation in advance, that is, show ASAs, while no ASAs were seen when a similar perturbation was triggered unexpectedly (EXP). Hence, elderly subjects are able to use feed-forward adjustments in multi-finger synergies in anticipation of a self-triggered perturbation. The pattern of change in the index of co-variation (ΔV) was similar to a pattern reported in a similar study of young subjects (Kim et al. 2006). However, in the study of younger persons, the magnitude of ΔV drop was significant 125 ms prior to the time of perturbation and its magnitude was about 0.2. In the current study, ΔV changes in the elderly emerged later (75 ms prior to t0), and their magnitude (0.06) was about one-third of that in younger persons.

In the earlier study of younger persons (Kim et al. 2006), the most independent (index) and least independent (ring) fingers were perturbed to explore possible difference across the fingers that could be due to their degree of individuation (cf. Zatsiorsky et al. 2000). The ASA characteristics were very similar for the perturbations applied to these two fingers suggesting that the main result could be generalized to all other fingers of the hand. Only one finger was perturbed in this study to shorten the experiment and help avoid fatigue in the elderly participants. The middle finger was selected as an “in-between” finger, which is neither most nor least independent. Because of these reasons, we view comparison of the presented data to the data reported by Kim and colleagues as valid.

The findings of smaller and delayed ASAs resemble closely the observations of the smaller and delayed anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs) in the elderly (Woollacott & Manchester, 1993). In both studies, feed-forward adjustments to a self-triggered perturbation could be generated by the elderly subjects, but these adjustments were smaller and closer in time to the action initiation. This age-related change may contribute to the well documented impairment of the manual dexterity and quality of life with age (Francis & Spirduso, 2000; Giampaoli et al. 1999).

Another potentially important finding is the change in the sharing pattern of the total force between the perturbed finger (M) and other fingers (IRL) after the perturbation. The perturbed finger increased its share by approximately 7-8% which is similar to the change in sharing pattern reported in an earlier study of younger subjects (Kim et al. 2006). This result reflects the preserved ability of elderly persons to explore the flexibility of the mechanically redundant multi-finger system and find different solutions for the task of force production.

Acknowledgments

The screening process of the elderly subjects was conducted at the General Clinical Research Center (The Pennsylvania State University).

The study was in part supported by NIH grants AG-018751, NS-035032, AR-048563, and M01 RR-10732.

References

- Bouisset S, Zattara M. Biomechanical study of the programming of anticipatory postural adjustments associated with voluntary movement. Journal of Biomechanics. 1987;20:735–742. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danion F, Schöner G, Latash ML, Li S, Scholz JP, Zatsiorsky VM. A force mode hypothesis for finger interaction during multi-finger force production tasks. Biological Cybernetics. 2003;88:91–98. doi: 10.1007/s00422-002-0336-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis KL, Spirduso WW. Age differences in the expression of manual asymmetry. Experimental Aging Research. 2000;26:169–180. doi: 10.1080/036107300243632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giampaoli S, Ferrucci L, Cecchi F, Lo Noce C, Poce A, Dima F, Santaquilani A, Vescio MF, Menotti A. Hand-grip strength predicts incident disability in non-disabled older men. Age and Ageing. 1999;28:283–288. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW, Shim JK, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Anticipatory adjustments of multi-finger synergies in preparation for self-triggered perturbations. Experimental Brain Research. 2006;174:604–612. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Scholz JP, Schöner G. Motor control strategies revealed in the structure of motor variability. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2002;30:26–31. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massion J. Movement, posture and equilibrium: Interaction and coordination. Progress in Neurobiology. 1992;38:35–56. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90034-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir H, Yoshida N, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Anticipatory covariation of finger forces during self-paced and reaction time force production. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;381:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir H, Yoshida N, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Elderly show decreased adjustments of motor synergies in preparation to action. Clinical Biomechanics (Bristol, Avon. 2007;22:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves ND, Narici MV, Maganaris CN. Myotendious plasticity to ageing and resistance exercise in humans. Experimental Physiology. 2006;91:483–498. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Danion F, Latash ML, Schöner G. Understanding finger coordination through analysis of the structure of force variability. Biological Cybernetics. 2002;86:29–39. doi: 10.1007/s004220100279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JK, Olafsdottir H, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. The emergence and disappearance of multi-digit synergies during force production tasks. Experimental Brain Research. 2005;164:260–270. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2248-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JK, Latash ML, Zatsiorsky VM. Prehension synergies. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;93:766–776. doi: 10.1152/jn.00764.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M, Li S, Kang N, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Effects of age and gender on finger coordination in maximal contractions and submaximal force matching tasks. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;94:259–270. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00643.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woollacott MH, Manchester DL. Anticipatory postural adjustments in older adults: are changes in response characteristics due to changes in strategy? Journal of Gerontology. 1993;48:M64–M70. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.2.m64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatsiorsky VM, Li Z-M, Latash ML. Enslaving effects in multi-finger force production. Experimental Brain Research. 2000;131:187–195. doi: 10.1007/s002219900261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]