Abstract

Post-transcriptional modification is a ubiquitous feature of ribosomal RNA in all kingdoms of life. Modified nucleotides are generally clustered in functionally important regions of the ribosome, but the functional contribution to protein synthesis is not well understood. Here we describe high resolution crystal structures for the N2-guanine methyltransferase RsmC that modifies residue G1207 in 16 S rRNA near the decoding site of the 30 S ribosomal subunit. RsmC is a class I S-adenosyl-l-methionine-dependent methyltransferase composed of two methyltransferase domains. However, only one S-adenosyl-l-methionine molecule and one substrate molecule, guanosine, bind in the ternary complex. The N-terminal domain does not bind any cofactor. Two structures with bound S-adenosyl-l-methionine and S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine confirm that the cofactor binding mode is highly similar to other class I methyltransferases. Secondary structure elements of the N-terminal domain contribute to cofactor-binding interactions and restrict access to the cofactor-binding site. The orientation of guanosine in the active site reveals that G1207 has to disengage from its Watson-Crick base pairing interaction with C1051 in the 16 S rRNA and flip out into the active site prior to its modification. Inspection of the 30 S crystal structure indicates that access to G1207 by RsmC is incompatible with the native subunit structure, consistent with previous suggestions that this enzyme recognizes a subunit assembly intermediate.

Post-transcriptional modification is a ubiquitous feature of rRNA in all kingdoms of life. The position of many modified nucleotides is conserved and generally located in functionally important regions in the ribosome (1), although the functions have been identified for few of the modifications. There are three basic types of rRNA modifications as follows: pseudouridylation, base methylation, and ribose methylation. N2-Methylation of guanine is the second most abundant modification in rRNA after pseudouridine formation (reviewed in Ref. 2). Complete modification maps of bacterial rRNA have been constructed for only two species, Escherichia coli and Thermus thermophilus (3). Given the divergent conditions for growth of these organisms, it was unexpected that they differ little in their 16 S rRNA modifications. E. coli 16 S rRNA has 11 modifications, whereas T. thermophilus has 14, with 9 modifications being identical between the two species. A similar situation applies to the 23 S rRNA (4). Thus, it is predicted that there will be significant similarity in the enzymology of modification of these two organisms.

A number of enzymes responsible for rRNA modification in E. coli have been identified and characterized, and several structures have been solved. However, little is known about how these enzymes recognize their substrates or, in many instances, what those substrates actually are. Some methyltransferases, such as KsgA, recognize subunit assembly intermediates (5), whereas others, such as RsmG, appear to methylate subunits once assembly has been completed (6–8). Only the structures of the 5-methyluridine methyltransferases RlmD and TrmA are known in complex with their respective RNA substrates (9, 10).

RsmC (EC 2.1.1.52) is an AdoMet2-dependent methyltransferase responsible for N2-methylation of G1207 in 16 S rRNA and was first described in 1999 (11). AdoMet-dependent methyltransferases are divided into five structurally different classes (12, 13). RsmC belongs to the largest class I family, which is characterized by a central seven-stranded β-sheet that is flanked by three helices on each side and is structurally similar to Rossmann-fold domains. Class I methyltransferases modify a wide variety of substrates, including nucleic acids and proteins. Substrate specificity is achieved by additional substrate recognition domains in many of these enzymes (14).

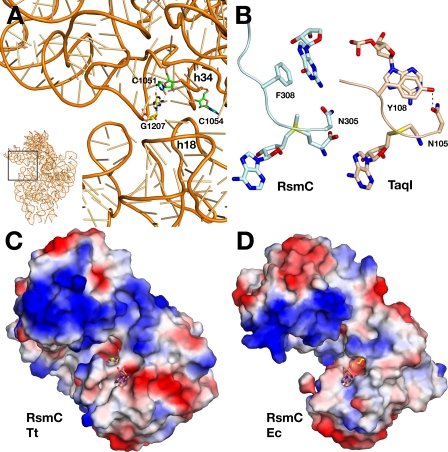

The target of RsmC, G1207 (E. coli numbering), is situated in helix 34 of 16 S rRNA (15), a component of the ribosome long known to be involved in codon recognition, and forms a Watson-Crick base pair with C1051. Substitutions at C1054 or C1200 act as suppressors of nonsense mutations (16, 17), whereas a number of substitutions at or near these positions have been shown to influence decoding accuracy (18). These data can now be rationalized using crystal structures of the 30 S subunit from T. thermophilus in which C1054 can be seen to participate directly in codon recognition through interactions with the codon-anticodon complex (19). Thus, like a number of methylated nucleotides of 16 S rRNA, G1207 is in a position to potentially influence the fidelity of codon recognition. Substitutions at G1207 produce dominant-lethal phenotypes (20), although this may result more from effects on local RNA structure than on the methylation status of this base because rsmC is dispensable (21). A role for RsmC in 30 S subunit assembly has been suggested based on the observation that the enzyme most efficiently methylates 30 S subunits at low magnesium concentrations, although the physiological relevance of this observation is far from clear (11).

The structure of the apo-form of E. coli RsmC was recently solved (21) revealing that the enzyme is composed of two domains with nearly identical folds, presumably the result of a gene duplication event. It was not clear from this structure precisely how the cofactor AdoMet or the substrate guanosine would dock into the active site. To gain insights into the substrate recognition mechanism, we determined high resolution crystal structures of RsmC from the extreme thermophile T. thermophilus in a ternary complex with AdoMet and guanosine bound in the active site as well as in complexes with AdoMet or AdoHcy. The orientation of the guanine base in the active site clearly shows that the substrate G1207 needs to disengage from its Watson-Crick interaction with C1051 in the context of the 16 S rRNA structure. In addition, the base orientation is guided by hydrophobic stacking interactions with protein residues in a manner similar to class I N6-adenine DNA methyltransferases, and the modified nitrogen atom is located in a similar position in the active site. However, the direction of base insertion into the active site is dissimilar, and the mechanism of overall substrate recognition is unlikely to be related between the two enzymes. Structural comparison with RsmC from E. coli reveals a conserved positively charged surface region in the noncatalytic domain that is not detected by sequence alignment but may function in rRNA binding.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning—The full-length rsmC gene (GenBank™ accession number YP_143799) from T. thermophilus HB8 genomic DNA was amplified by PCR using a forward primer containing an NdeI restriction site (GGAATTCATATGAGCCTGAC-GCGGGAAGC) and a reverse primer containing a NotI restriction site (GGGTGCGGCCGCCCTCCCTCGCTTTTCCGCGAAC). PCRs were performed using a touchdown protocol in the presence of 4% DMSO. The amplified insert of rsmC gene was cloned into the expression vector pET26b (Novagen) and transformed into E. coli DH5α cloning strain and plated onto LB-kanamycin plates. The plasmid was isolated and transformed into an E. coli BL21 DE3 star expression strain (Invitrogen). The expression construct contained a C-terminal hexahistidine tag.

Protein Expression and Purification—Bacterial cells were grown to mid-log phase in LB media at 37 °C in the presence of 35 μg/ml kanamycin. Protein expression was induced at 20 °C by introduction of 400 μm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. Cells were pelleted after 18 h by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. Bacterial cells were lysed by ultrasonification on ice in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris (pH 8.5), 300 mm NaCl, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 5% glycerol. Cell debris and membranes were pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. The soluble proteins were heat-treated at 65 °C for 30 min to precipitate E. coli proteins. Heat-denatured E. coli proteins were separated by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min. The soluble C-terminally hexahistidine-tagged T. thermophilus RsmC was further purified by affinity chromatography with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen). Untagged proteins were removed with a buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) and 250 mm NaCl and 10 mm imidazole (pH 8.5). Recombinant RsmC was then eluted with the same buffer containing 150 mm imidazole, and eluted protein was immediately mixed with 5% v/v glycerol. RsmC was unstable and aggregated in the absence of glycerol. The protein was further purified with anion exchange chromatography (QFF) (GE Healthcare) at pH 8.5, using a linear gradient of 10 mm to 1 m NaCl concentration. RsmC fractions were pooled and concentrated and applied to a size exclusion chromatography S200 column (GE Healthcare) at pH 8.5 and 200 mm NaCl. The purified RsmC was concentrated to 24 mg/ml in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris (pH 8.5), 200 mm NaCl, and 5% v/v glycerol for crystallization trials. The C-terminal hexahistidine tag was not removed for crystallization. For the production of selenomethionyl proteins, the expression construct was transformed into B834(DE3) cells (Novagen). The bacterial growth was carried out in defined LeMaster medium (22), and the protein was purified using the same protocol as for the wild-type protein. To form the RsmC-AdoHcy complex, purified RsmC was mixed with 2 mm AdoHcy, incubated at 50 °C for 10 min, and slowly cooled down to room temperature. To form the RsmC-AdoMet-guanosine complex, purified RsmC was mixed with 2 mm chloride salt of AdoMet and 1 mm guanosine hydrate and incubated at 50 °C for 10 min before performing crystallization experiments.

Crystallization—Crystals of RsmC complexed with AdoMet and AdoHcy were obtained with the microbatch technique under oil at 4 °C. 1 μl of protein solution was mixed with the reservoir solution, which contained 0.1 m HEPES (pH 7.5) and 1.5 m lithium sulfate monohydrate. Initial crystals grew over the course of 3–5 days with maximum dimensions of 0.6 × 0.6 × 0.6 mm. Crystals of RsmC in complex with AdoMet and guanosine hydrate were obtained with the microbatch technique under oil at 4 °C. 1 μl of protein solution was mixed with the reservoir solution, which contained 0.17 m lithium sulfate monohydrate, 0.085 m Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 25.5% w/v PEG4000, and 15% glycerol. Crystals grew over the course of 3–5 days with maximum dimensions of 0.6 × 0.6 × 0.6 mm. Crystals of the RsmC-AdoMet-guanosine ternary complex were flash-frozen by plunging into liquid nitrogen directly from their mother liquor, whereas RsmC-AdoMet and RsmC-AdoHcy crystals were cryo-protected by rapid soaking into a solution containing mother liquor supplemented with the addition of 30% v/v glycerol before freezing.

Data Collection—X-ray diffraction data for all crystals were collected on a MAR CCD detector at the X4C beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source in Brookhaven. For the initial structure determination, a selenomethionyl single wavelength anomalous dispersion data set to 1.9 Å resolution was collected at a wavelength of 0.979 Å at -180 °C. A single crystal was used for each data set. The diffraction images were processed and scaled with the HKL2000 package (23). To obtain higher resolution data, a second data set was collected on a larger crystal to 1.55 Å resolution. The crystals belong to the space group P212121, with cell dimensions of a = 50.7 Å, b = 88.4 Å, and c = 95.4 Å. There is a single molecule in the asymmetric unit, giving a Vm of 2.53 Å3/dalton. Cell dimensions of the ternary complex were a = 50.9 Å, b = 86.2 Å, and c = 95.1 Å. Diffraction data for the AdoHcy-bound form were collected to 1.55 Å resolution from a crystal grown in the presence of 2 mm AdoHcy at 4 °C. The data processing statistics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| RsmC1 AdoMet + guanosine | RsmC2 AdoHcy | RsmC3 AdoMet | RsmC4 anomalous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 50.9, 86.2, 95.1 | 51.0, 88.0, 94.9 | 50.7, 88.4, 95.4 | 51.1, 86.5, 95.1 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30 to 1.55 (1.61 to 1.55) | 30 to 1.55 (1.61 to 1.55) | 30 to 1.58 (1.64 to 1.58) | 30 to 1.9 (1.97 to 1.90) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.066 (0.418) | 0.059 (0.357) | 0.051 (0.398) | 0.035 (0.198) |

| I/σI | 23.8 (2.2) | 24.7 (2.6) | 27.3 (3.0) | 50.2 (8.5) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.8 (81.6) | 99.1 (96.5) | 98.6 (92.4) | 100 (100) |

|

Redundancy

|

5.7 (3.1)

|

5.5 (4.6)

|

5.9 (4.2)

|

6.4 (5.5)

|

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 1.55 (1.59 to 1.55) | 1.55 (1.59 to 1.55) | 1.58 (1.62 to 1.58) | |

| No. of reflections | 57,244 (3603) | 58,855 (4186) | 55,718 (3766) | |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.19/0.23 (0.30/0.32) | 0.18/0.22 (0.27/0.30) | 0.18/0.22 (0.26/0.29) | |

| No. of atoms | ||||

| Protein | 2842 | 2867 | 2868 | |

| Ligands | 45 | 26 | 27 | |

| Sulfate ions | 10 | 30 | 30 | |

| Water | 502 | 729 | 699 | |

| B-factors | ||||

| Protein | 22.66 | 23.78 | 24.43 | |

| Ligands | 21.02 | 14.96 | 17.78 | |

| Sulfate ions | 35.07 | 49.27 | 41.95 | |

| Water | 33.44 | 37.25 | 38.16 | |

| r.m.s.d. | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.010 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

Structure Determination and Refinement—The locations of three selenium atoms (out of four expected selenium atoms) were determined with the program Solve (24) based on the anomalous differences in the single wavelength anomalous data set. Reflection phases to 1.9 Å were calculated with Solve. An initial model was built by Resolve (25), and ARP/wARP (26, 27) was used for subsequent model building. The atomic coordinates from the first model were then used as initial models for refinement against all three complex data sets. All models were checked and completed with Coot (28). Crystallographic refinement was performed with the program Refmac (29) from the CCP4 package (30). Final models of all three structures contain residues 3–372 in chain A. Residues of the C-terminal hexahistidine tag were disordered and not included in the final models. The stereochemical quality of the models was assessed with Procheck (31). The Ramachandran statistics (most favored/additionally allowed/generously allowed/disallowed) are 94.5/4.9/0.6/0.0% for RsmC1, 94.2/5.2/0.6/0.0% for RsmC2, and 94.5/4.9/0.6/0.0% for RsmC3. The refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. Figures were generated using Pymol (32) and JalView (33). Sequence alignments were generated with ClustalW2 (34) and Staccato (35).

Atomic Coordinates—The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 3DMH, 3DMG, and 3DMF for RsmC1, RsmC2, and RsmC3, respectively.

RESULTS

Overall Structure of RsmC—The structure of RsmC (375 amino acids) was solved by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion methods from seleno-methionine-labeled protein in space group P212121 initially to 1.9 Å resolution (data set RsmC4). We report three high resolution structures (up to 1.55 Å) for the enzyme in complex with guanosine and AdoMet, in complex with AdoHcy, and in complex with AdoMet (referred to as RsmC1, RsmC2, and RsmC3, respectively). The crystallographic R/Rfree factors are 0.19/0.23, 0.18/0.22, and 0.18/0.22 for the data sets, respectively. The structures are highly similar with an overall root mean square deviation of 0.19 Å between RsmC1 and RsmC2. There is one molecule in the asymmetric unit. The majority of residues (94.5/94.2/94.5%) are in the most favored region of the Ramachandran plot, and there are no residues in the disallowed region. In all three structures, electron density was well defined except for the first two and last three residues and for residues 309–314 in a loop region near the active site (discussed below). The data collection and refinement statistics are given in Table 1.

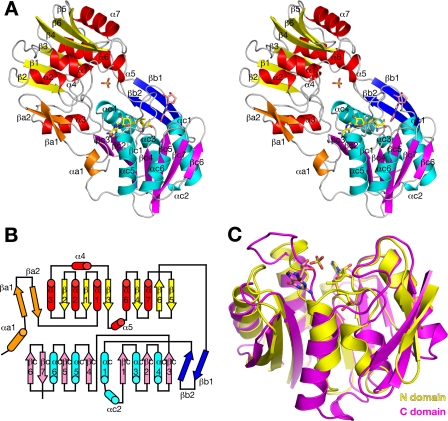

The overall structure of RsmC consists of two structurally related domains (residues 3–175 and residues 187–373) connected by a short linker region (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2A), probably the result of a gene duplication event followed by domain subfunctionalization (21). Both domains form a canonical Rossmann-like methyltransferase fold with minor variations (Fig. 2B). The N-terminal domain consists of a six-stranded β-sheet that is flanked on both sides by six helices of varying length. The C-terminal domain consists of a seven-stranded β-sheet flanked by five helices. Both domains contain an additional β-hairpin that is also observed in other methyltransferases and forms a highly conserved hydrophobic interface with the core domain. There is one AdoMet and one guanosine molecule bound to the C-terminal catalytic domain, whereas the N-terminal domain contains a bound sulfate ion (from the precipitant used for crystallization). The first helixαa1 is the only unique secondary structure element observed. It connects to the side of the C-terminal domain and contributes to the cofactor-binding site. The two domains in RsmC, including the β-hairpin, align with a least squares r.m.s.d. of 1.7 Å (Fig. 2C). Although the secondary structure elements generally align quite well, many small variations are observed especially in the loop regions flanking the cofactor- and substrate-binding sites of the catalytic domain.

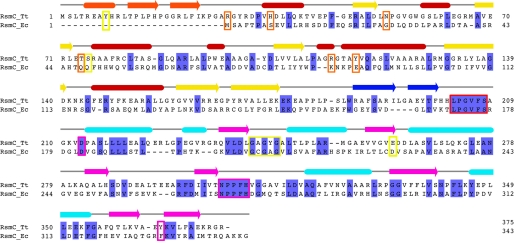

FIGURE 1.

Structure-based sequence alignment. Sequence alignment of RsmC from T. thermophilus and E. coli. Secondary structure elements of T. thermophilus RsmC are indicated on top. The color scheme for secondary structure elements is as in Fig. 2A. The position of conserved methyltransferase signature motifs is marked with red boxes. Residues occupying the N-terminal active site region in the N-terminal domain are marked with orange boxes; residues interacting with the cofactor are marked with yellow boxes, and residues interacting with guanosine are marked with magenta boxes.

FIGURE 2.

Overall structure of RsmC. A, stereo diagram showing a schematic representation of the overall structure. Secondary structure elements are colored in orange, yellow, and red in the N-terminal domain and in blue, cyan, and purple in the C-terminal domain. AdoMet is shown as yellow sticks with atoms colored by elements; guanosine is shown as salmon sticks, and a sulfate molecule bound in the noncatalytic domain is shown in yellow. B, topology diagram with secondary structure elements colored as in A. C, least squares superposition of the two subdomains. The catalytic domain is shown in magenta, and the N-terminal domain is shown in yellow. AdoMet and guanosine bound to the catalytic subdomain are shown as sticks.

Cofactor Binding in the Active Site of RsmC—In contrast to other methyltransferases, recombinant RsmC retains AdoMet tightly bound throughout purification and crystallization (data set RsmC3). AdoMet could be displaced only during crystallization in the presence of an excess of AdoHcy as observed in data set RsmC2. This in part may reflect the thermostable nature of this enzyme.

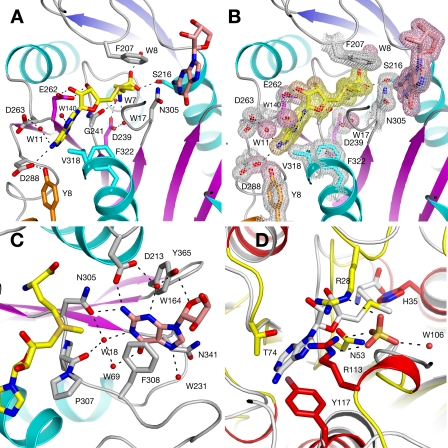

As in other class I methyltransferases, AdoMet is bound in a canonical conformation above the β-sheet and close to the conserved GXGXG methyltransferase signature motif (residues 241–245 between strand βc1 and helix αc3, see Fig. 1 and Fig. 3, A and B). The adenine ring is located in a mainly hydrophobic pocket that is lined by residues Phe-322 and Val-318 on one side and the main chain and C-β atom of Asp-263 on the other side. The presence of the charged aspartate in this position is unusual when compared with other methyltransferases; however, its participation in a hydrogen bond to the main-chain nitrogen of Arg-76 and the Ser-75 side chain might further stabilize the interdomain coordination in the thermophilic enzyme. The N6 atom of the adenine group is coordinated by a hydrogen bond to Asp-288, which also interacts with the Tyr-8 hydroxyl group from the N-terminal helix αa1. Both ribose hydroxyl groups form hydrogen bonds to Glu-262. This represents another variation in this structure, as position 262 in methyltransferases is typically occupied by an aspartate residue (as in RsmC from E. coli; a more comprehensive sequence alignment of RsmC homologs is given in supplemental Fig. S1). The Ser-216 side chain coordinates the methionine carboxyl group of the cofactor, and the methionine amino group interacts with the main-chain carbonyl of Gly-241 and with Asp-239 via solvent water molecules. Asn-305, which is also a conserved signature residue in the class I methyltransferase cofactor-binding site, engages in a hydrogen bond to the guanine N2 atom (2.9 Å), and its amino group nitrogen atom is located at a distance of 3.5 Å from the methionine carboxylate oxygen. The hydrophobic Phe-207 approaches the AdoMet sulfur atom and might contribute to the enzymatic function by destabilizing the cofactor. The presence of the noncatalytic N-terminal domain restricts the accessibility of the cofactor-binding site significantly. Helix αa1 and the loop region connecting βa2 with α1 effectively extend the adenine-binding pocket and create a deep cofactor-binding site that is likely only accessible in the absence of substrate rRNA. Both AdoMet and AdoHcy are bound in an identical manner. Phe-207 is the only residue that is shifted in the two structures, with the phenyl ring translating laterally by 0.6 Å (a comparison of AdoMet- and AdoHcy-binding is given in supplemental Fig. S2A).

FIGURE 3.

The RsmC active site. A, AdoMet binding in the active site. AdoMet and guanosine are shown as yellow and salmon sticks, respectively. Solvent water molecules are shown as red spheres. B, final SigmaA-weighted 2Fo - Fc electron density map of the active site region contoured at 1σ. C, guanosine binding in the active site. D, comparison of side chain orientation in the noncatalytic N-terminal domain with the active site region of the catalytic domain. Residues in the N-terminal domain are colored red and yellow. The C-terminal domain and AdoMet bound in the catalytic domain are shown in gray for reference.

The comparison of the cofactor-binding site in the catalytic domain with the equivalent region in the N-terminal domain shows the key differences rendering the N-terminal domain noncatalytic (Fig. 3D). Hydrophobic interactions of Val-318 and Glu-262 with the adenine base have been replaced with hydrogen-bonding Tyr-117 and Thr-74. More significantly, Arg-28, Arg-113, Asn-53, and His-35 extend into the cofactor-binding pocket precluding any AdoMet binding in the N-terminal domain. Instead, the role of this domain may be to engage in substrate-rRNA interactions. Consistent with this notion, Arg-28 and Arg-113 cooperate to bind the sulfate ion in the N-terminal domain and by analogy might function in coordinating a phosphate group from the substrate rRNA.

Guanosine Binding in the RsmC Active Site—The position of the guanosine molecule in the active site is mainly determined by a hydrophobic stacking interaction with the Phe-308 side chain and two hydrogen bonds of Asn-305 and Asp-213 with the substrate N2 nitrogen atom (Fig. 3C). Another hydrogen bond is established between Tyr-365 and the ribose oxygen atoms, and several solvent water-mediated hydrogen bonds are formed to the other nitrogen atoms and the carbonyl group of the base. The two hydroxyl groups of the ribose moiety are oriented toward the protein surface and are not engaged in hydrogen bonds with ordered solvent water molecules. Comparison of the guanosine-bound RsmC1 structure with the substrate-free RsmC2 structure shows that the Asn-341 side chain occupies the position of the guanosine N7 atom and that the Asn-341 side chain rotates by about 120° upon guanosine binding. In addition, the side chains of Asp-213, Phe-308, and Tyr-365 reorient slightly when guanosine is bound (supplemental Fig. S2C). To investigate the possibility that adenosine might also bind in the active site of RsmC, we performed the same experiment with adenosine instead of guanosine. However, there was no indication of adenosine binding in a 2.2-Å diffraction data set from crystals obtained under the same conditions as the guanosine-bound crystals (data not shown).

The RsmC-AdoMet-guanosine complex structure gives some insights into the recognition of the ribosome substrate. Guanosine is bound in a catalytically inactive state, as indicated by the distance (4.7 Å) between the AdoMet methyl group and the substrate N2 atom. The observed position of the guanine base suggests that a small shift may be sufficient to trigger catalysis (Fig. 3B). In our RsmC structure, the quality of the electron density for the loop region between residues 309 and 314 is notably weaker than anywhere else in the structure, and B-factors are higher for this region. Considering that the real substrate for RsmC consists of at least several nucleotides surrounding the G1207 base, a shift of the guanosine position toward the AdoMet methyl group might be accomplished by an induced-fit mechanism when the larger substrate is bound to RsmC. Thus, our structural data show how enzymatic activity is achieved specifically for a guanosine within the context of a larger rRNA substrate without sacrificing guanosine-binding interactions within the active site region.

DISCUSSION

Comparison with Structurally Related Methyltransferases—A data base search with the SSM algorithm (36) showed that the structure most closely related to T. thermophilus RsmC is E. coli RsmC (21) followed by a structure of unknown function (Protein Data Bank code 1DUS) from Methanococcus jannaschii, which has been proposed to represent the RsmC homolog from this organism (37). RsmC from E. coli is the only structure with the same two-domain architecture, whereas other structurally related methyltransferases share structural similarity for only the catalytic domain. RsmC from T. thermophilus and E. coli share only 26% identical residues with each other in the structure-based sequence alignment (Fig. 1), but the two structures can be superimposed with an r.m.s.d. of 1.6 Å for 292 C-α atoms. The RsmC C-terminal domain by itself also shows strong similarity to the catalytic domains of protein methyltransferases such as the ribosomal protein L11 trimethyltransferase PrmA (38). The r.m.s.d. of the catalytic domain with the T. thermophilus PrmA is 1.5 Å for 147 C-α atoms.

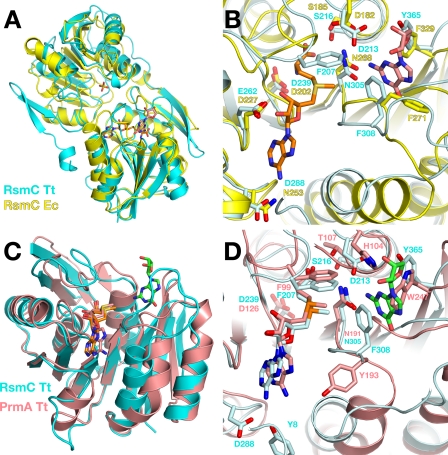

It is interesting to note that the thermophilic RsmC represents a complete domain duplication, whereas the mesophilic RsmC has lost the leading N-terminal β-hairpin (and the single N-terminal helix; Fig. 4A). These additional secondary structure elements contribute to the cofactor-binding site and create a better-defined binding pocket in our RsmC structure. The RsmC structure from E. coli was reported in the absence of cofactor or substrate suggesting that cofactor binding is significantly weaker in the absence of the N-terminal extension. Conversely, the higher cofactor-binding affinity of the Thermus enzyme is clearly reflected in our observation that the enzyme always co-purifies with bound cofactor. In addition, we found that extended dialysis of the cofactor-bound enzyme (up to 3 days in large volumes at 4 °C) did not suffice to remove the cofactor. The remaining interacting residues in the cofactor-binding site and the major determinants for guanosine placement are well conserved between both enzymes (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of cofactor binding with structurally related methyltransferases. A and B, comparison of RsmC from T. thermophilus and E. coli. The structure from T. thermophilus and E. coli are colored in cyan and in yellow, respectively. AdoMet is shown as orange sticks, and guanosine is shown as salmon sticks. C and D, comparison with the PrmA protein lysine methyltransferase. PrmA and its bound cofactor are colored in salmon; RsmC is colored in cyan, and guanosine is colored in green.

A significant difference between both structures is seen in the loop region surrounding Phe-207. The side chain of this residue approaches the AdoMet reactive methyl group, and the hydrophobic environment in the active site might contribute to catalysis. Phe-207 is conserved in the sequence alignment, but the location of the corresponding Phe-176 in E. coli is further removed from the AdoMet-binding site. In addition, the Phe-176 side chain was not modeled in the E. coli structure, suggesting that this loop region is flexible in the absence of cofactor. A similar structural flexibility of this loop has also been observed for the PrmA trimethyltransferase (discussed below). The side chain conformations for residues equivalent to Asp-213 and Phe-308 in the guanosine-binding region are different in the E. coli structure in the absence of guanosine suggesting a structural rearrangement upon substrate binding. Tyr-365 is replaced with Phe-329 in E. coli, and the formation of the hydrophobic cavity for base insertion seems therefore more important than the hydrogen bond formation with the substrate ribose oxygen observed in the Thermus structure. Overall, the active site is more constricted, and there are more hydrogen bond interactions found in RsmC from T. thermophilus, which is consistent with the general observation that there are more bonding interactions present in thermophilic enzyme structures.

Comparison with Functionally Unrelated Methyltransferases—Structural comparison with the functionally unrelated protein trimethyltransferase PrmA illustrates the degree of conservation among class I methyltransferases with respect to cofactor binding (Fig. 4, C and D). The similarity of the overall geometry is striking. The position of the AdoMet cofactor remains identical, and most of the binding interactions are conserved. Not surprisingly, side chains involved in guanosine placement in RsmC are not conserved in PrmA. Replacement of Tyr-365 with Trp-247 effectively closes off the guanosine-binding site in PrmA. Phe-308 is replaced with Tyr-193 in PrmA that is oriented in the opposite direction and interacts with the AdoMet base as a functional replacement of Tyr-8 in RsmC (the N-terminal β-hairpin is not present in PrmA).

The position of Phe-207 in RsmC is equivalent to Phe-99 in PrmA. The loop region surrounding Phe-99 contains several glycine residues and is disordered in several structures in the absence of cofactor. A highly similar loop and phenylalanine placement are also observed in the PrmC protein methyltransferase (39). These combined observations led us to propose a functional significance for the observed flexibility and the induced fit of this loop upon cofactor binding. In combination with the significant difference of this loop region in the apo-RsmC structure from E. coli, it seems likely that a similar induced fit mechanism is present in these enzymes. Further studies will be required to determine the functional significance of these observations.

Implications for rRNA Binding—The RsmC target site, G1207, is located in helix 34 of 16 S rRNA and base pairs with C1051 (Fig. 5A). The orientation of guanosine in our RsmC-AdoMet-guanosine ternary complex structure shows that G1207 has to disengage from its Watson-Crick pairing with C1051 and flip out of the helix to insert into the RsmC active site. Such base flipping in RNA-enzyme complexes has been observed previously. The TruB pseudouridine synthase-RNA complex revealed that three bases flip from the tRNA analog T loop to insert U55 into the active site for pseudouridylation (40). A number of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-tRNA co-crystal structures indicate that these enzymes differentiate among tRNAs by flipping out and monitoring the anticodon bases (reviewed in Ref. 41). The flipping out of G1207 is unique in that this base engages in Watson-Crick pairing in the context of the ribosome.

FIGURE 5.

Implications for substrate binding. A, schematic representation of the 16 S rRNA. The substrate G1207, the base-pairing C1051, and the functionally important C1054 are shown as sticks. The position of the close-up figure in the rRNA structure is indicated in the lower left figure. The positions of helices 34 and 18 are indicated. B, comparison of substrate base orientation between RsmC (left) and TaqI (right). The cofactor (cofactor homolog in TaqI) is shown at the bottom and the substrate base at the top of each figure. C and D, surface representation colored by electrostatic charge for RsmC from T. thermophilus and E. coli. AdoMet is shown as yellow sticks and guanosine as salmon sticks. AdoMet and guanosine from the Thermus structure are shown with the E. coli structure for comparison.

Nucleotide flipping has also been observed for DNA methyltransferases such as the C5-cytosine methyltransferase M.HhaI (42) or the N6-adenine methyltransferase TaqI (43, 44). A functional similarity between RsmC and N6-adenine methyltransferases has been proposed based on sequence analysis and the conservation of the 305NPPF308 signature motif (105NPPY108 in TaqI, Protein Data Bank code 1G38 (45)). Phe-308 provides the base stacking interaction for the substrate guanine in RsmC. The structural comparison of this region with TaqI shows that Tyr-108 provides the same hydrophobic interaction for the substrate base (Fig. 5B). However, the tyrosine hydroxyl group engages in a hydrogen bond with Asn-105 that repositions the tyrosine side chain and results in a substantially different orientation of the substrate base. Thus, simple replacement of Phe with Tyr results in a significantly different base insertion direction and contributes to the differing catalytic activity between these two enzyme families.

Implications for Ribosome Binding—Inspection of the 30 S subunit crystal structure (46) indicates that access to G1207 by RsmC would be occluded in the native structure by helix 18 (Fig. 5A) and would require either rotation of the 30 S head around the neck region or a substantial backward motion toward the solvent side of the subunit. Movement of the head relative to the rest of the 30 S subunit occurs with the open-closed transition during codon recognition (47) suggesting that the capacity of this structure to engage in such motions is an intrinsic feature. The observation that methylation of 30 S subunits by RsmC is more efficient at low magnesium concentration (0.9 mm) than at high magnesium concentration (6 mm) has been taken to imply that a subunit assembly intermediate is the actual substrate (11). Alternatively, low magnesium conditions may allow greater freedom of motion of the head. What would facilitate such motion in vivo is unclear, although restriction of head motion might be established by one or more late binding proteins, such as S2, which has binding sites on both the head and the body of the 30 S subunit (46). Other methyltransferases, such as KsgA, modify the ribosome prior to completion of assembly, and negative determinants for modification are the incorporation of one or more ribosomal proteins (5). In this context, it is interesting to note that the noncatalytic domains of both RsmC structures place a positively charged surface area close to the active site that suggests a functional contribution of the duplicated N-terminal domain for substrate rRNA binding (Fig. 5, C and D). Although this observation is consistent with the functional requirements for these enzymes, the residues contributing to the charged surface patch are not conserved between RsmCs from different organisms (supplemental Fig. S1).

Despite the presence of RsmC orthologs among bacteria and the proximity of G1207 to C1054 and the site of codon recognition, the base identity at position 1207 of bacterial 16 S rRNAs is somewhat variable. The 1051:1207 base pair is found almost entirely as G-C and C-G at similar frequencies (15), raising the obvious question as to the function of RsmC in species havingaCat position 1207. Substitutions at G1207 produce dominant-lethal phenotypes in E. coli (20) suggesting that Watson-Crick pairing of G1207 and C1051 is essential for maintaining a conformation of C1054 suitable for participation in codon recognition. The local structure of this helix is quite remarkable as it contains several bases splayed out of the helix as well as two sharp reversals of backbone trajectory that are established by multiple noncanonical base pairings and several base-triple interactions. One possible role for the interaction of RsmC with helix 34 may be to aid in pre-organization of this highly unorthodox structure and prevent misfolding during 30 S subunit assembly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ashwin Cadambi, Megha Katti, Siqing He, and Holly Careskey for their assistance with crystallization experiments; John Schwanof and Randy Abramowitz for access to the X4C beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source; and Hua Li for help with data collection at the synchrotron.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3DMF, 3DMG, and 3DMH) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM19756 (to A. E. D.). This work was also supported by Brown University (to G. J.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: AdoMet, S-adenosyl-l-methionine; AdoHcy, S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine; r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation.

References

- 1.Decatur, W. A., and Fournier, M. J. (2002) Trends Biochem. Sci. 27 344-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sergiev, P. V., Bogdanov, A. A., and Dontsova, O. A. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35 2295-2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guymon, R., Pomerantz, S. C., Crain, P. F., and McCloskey, J. A. (2006) Biochemistry 45 4888-4899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mengel-Jorgensen, J., Jensen, S. S., Rasmussen, A., Poehlsgaard, J., Iversen, J. J. L., and Kirpekar, F. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 22108-22117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu, Z., O'Farrell, H. C., Rife, J. P., and Culver, G. M. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15 534-536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okamoto, S., Tamaru, A., Nakajima, C., Nishimura, K., Tanaka, Y., Tokuyama, S., Suzuki, Y., and Ochi, K. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 63 1096-1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura, K., Johansen, S. K., Inaoka, T., Hosaka, T., Tokuyama, S., Tahara, Y., Okamoto, S., Kawamura, F., Douthwaite, S., and Ochi, K. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189 6068-6073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishimura, K., Hosaka, T., Tokuyama, S., Okamoto, S., and Ochi, K. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189 3876-3883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee, T. T., Agarwalla, S., and Stroud, R. M. (2005) Cell 120 599-611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alian, A., Lee, T. T., Griner, S. L., Stroud, R. M., and Finer-Moore, J. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 6876-6881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tscherne, J. S., Nurse, K., Popienick, P., and Ofengand, J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 924-929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozbial, P. Z., and Mushegian, A. R. (2005) BMC Struct. Biol. 5

- 13.Schubert, H. L., Blumenthal, R. M., and Cheng, X. D. (2003) Trends Biochem. Sci. 28 329-335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin, J. L., and McMillan, F. M. (2002) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12 783-793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannone, J. J., Subramanian, S., Schnare, M. N., Collett, J. R., D'Souza, L. M., Du, Y. S., Feng, B., Lin, N., Madabusi, L. V., Muller, K. M., Pande, N., Shang, Z. D., Yu, N., and Gutell, R. R. (2002) BMC Bioinformatics 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Goringer, H. U., Hijazi, K. A., Murgola, E. J., and Dahlberg, A. E. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88 6603-6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregory, S. T., and Dahlberg, A. E. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res. 23 4234-4238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moine, H., and Dahlberg, A. E. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 243 402-412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogle, J. M., Brodersen, D. E., Clemons, W. M., Tarry, M. J., Carter, A. P., and Ramakrishnan, V. (2001) Science 292 897-902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jemiolo, D. K., Taurence, J. S., and Giese, S. (1991) Nucleic Acids Res. 19 4259-4265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunita, S., Purta, E., Durawa, M., Tkaczuk, K. L., Swaathi, J., Bujnicki, J. M., and Sivaraman, J. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35 4264-4274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendrickson, W. A., Horton, J. R., and Lemaster, D. M. (1990) EMBO J. 9 1665-1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otwinowski, Z., and Minor, W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276 307-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terwilliger, T. C., and Berendzen, J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55 849-861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwilliger, T. C. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56 965-972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen, S. X., Morris, R. J., Fernandez, F. J., Ben Jelloul, M., Kakaris, M., Parthasarathy, V., Lamzin, V. S., Kleywegt, G. J., and Perrakis, A. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60 2222-2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perrakis, A., Morris, R., and Lamzin, V. S. (1999) Nat. Struct. Biol. 6 458-463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emsley, P., and Cowtan, K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60 2126-2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A., and Dodson, E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53 240-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey, S. (1994) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50 760-763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S., and Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26 283-291 [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeLano, W. L. (2004) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA

- 33.Clamp, M., Cuff, J., Searle, S. M., and Barton, G. J. (2004) Bioinformatics (Oxf.) 20 426-427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larkin, M. A., Blackshields, G., Brown, N. P., Chenna, R., McGettigan, P. A., McWilliam, H., Valentin, F., Wallace, I. M., Wilm, A., Lopez, R., Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J., and Higgins, D. G. (2007) Bioinformatics (Oxf.) 23 2947-2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shatsky, M., Nussinov, R., and Wolfson, H. J. (2006) Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinformat. 62 209-217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krissinel, E., and Henrick, K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60 2256-2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bujnicki, J. M., and Rychlewski, L. (2002) BMC Bioinformatics 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Demirci, H., Gregory, S. T., Dahlberg, A. E., and Jogl, G. (2007) EMBO J. 26 567-577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schubert, H. L., Phillips, J. D., and Hill, C. P. (2003) Biochemistry 42 5592-5599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoang, C., and Ferre-D'Amare, A. R. (2001) Cell 107 929-939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cusack, S., Yaremchuk, A., and Tukalo, M. (1998) in The Many Faces of RNA (Eggleston, D. S., Prescott, C. D., and Pearson, N. D. eds) pp. 55-65, Academic Press, London

- 42.Shieh, F. K., Youngblood, B., and Reich, N. O. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 362 516-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lenz, T., Bonnist, E. Y. M., Pljevaljcic, G., Neely, R. K., Dryden, D. T. F., Scheidig, A. J., Jones, A. C., and Weinhold, E. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 6240-6248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goedecke, K., Pignot, M., Goody, R. S., Scheidig, A. J., and Weinhold, E. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 121-125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bujnicki, J. M. (2000) FASEB J. 14 2365-2368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wimberly, B. T., Brodersen, D. E., Clemons, W. M., Morgan-Warren, R. J., Carter, A. P., Vonrhein, C., Hartsch, T., and Ramakrishnan, V. (2000) Nature 407 327-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogle, J. M., Murphy, F. V., Tarry, M. J., and Ramakrishnan, V. (2002) Cell 111 721-732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.