Abstract

In the medullary thick ascending limb, inhibiting the basolateral NHE1

Na+/H+ exchanger with nerve growth factor (NGF) induces

actin cytoskeleton remodeling that secondarily inhibits apical NHE3 and

transepithelial  absorption. The

inhibition by NGF is mediated 50% through activation of extracellular

signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Here we examined the signaling pathway

responsible for the remainder of the NGF-induced inhibition. Inhibition of

absorption. The

inhibition by NGF is mediated 50% through activation of extracellular

signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Here we examined the signaling pathway

responsible for the remainder of the NGF-induced inhibition. Inhibition of

absorption was reduced 45% by the

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors wortmannin or LY294002 and 50%

by rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a

downstream effector of PI3K. The combination of a PI3K inhibitor plus

rapamycin did not cause a further reduction in the inhibition by NGF. In

contrast, the combination of a PI3K inhibitor plus the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126

completely eliminated inhibition by NGF. Rapamycin decreased NGF-induced

inhibition of basolateral NHE1 by 45%. NGF induced a 2-fold increase in

phosphorylation of Akt, a PI3K target linked to mTOR activation, and a

2.2-fold increase in the activity of p70 S6 kinase, a downstream effector of

mTOR. p70 S6 kinase activation was blocked by wortmannin and rapamycin,

consistent with PI3K, mTOR, and p70 S6 kinase in a linear pathway.

Rapamycin-sensitive inhibition of NHE1 by NGF was associated with an increased

level of phosphorylated mTOR in the basolateral membrane domain. These

findings indicate that NGF inhibits

absorption was reduced 45% by the

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors wortmannin or LY294002 and 50%

by rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a

downstream effector of PI3K. The combination of a PI3K inhibitor plus

rapamycin did not cause a further reduction in the inhibition by NGF. In

contrast, the combination of a PI3K inhibitor plus the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126

completely eliminated inhibition by NGF. Rapamycin decreased NGF-induced

inhibition of basolateral NHE1 by 45%. NGF induced a 2-fold increase in

phosphorylation of Akt, a PI3K target linked to mTOR activation, and a

2.2-fold increase in the activity of p70 S6 kinase, a downstream effector of

mTOR. p70 S6 kinase activation was blocked by wortmannin and rapamycin,

consistent with PI3K, mTOR, and p70 S6 kinase in a linear pathway.

Rapamycin-sensitive inhibition of NHE1 by NGF was associated with an increased

level of phosphorylated mTOR in the basolateral membrane domain. These

findings indicate that NGF inhibits

absorption in the medullary thick

ascending limb through the parallel activation of PI3K-mTOR and ERK signaling

pathways, which converge to inhibit NHE1. The results identify a role for mTOR

in the regulation of Na+/H+ exchange activity and

implicate NHE1 as a possible downstream effector contributing to mTOR's

effects on cell growth, proliferation, survival, and tumorigenesis.

absorption in the medullary thick

ascending limb through the parallel activation of PI3K-mTOR and ERK signaling

pathways, which converge to inhibit NHE1. The results identify a role for mTOR

in the regulation of Na+/H+ exchange activity and

implicate NHE1 as a possible downstream effector contributing to mTOR's

effects on cell growth, proliferation, survival, and tumorigenesis.

The Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE12 is expressed ubiquitously in the plasma membrane of nonpolarized cells and in the basolateral membrane of epithelial cells, where it plays essential roles in basic cell functions such as the maintenance of intracellular pH (pHi) and cell volume (1–3). NHE1 is involved in other important cellular processes, including proliferation, survival, adhesion, migration, and tumor formation (2–7). These specialized functions involve regulation of NHE1 by a variety of receptor-mediated signaling networks as well as physical interactions of NHE1 with the actin cytoskeleton (2, 3, 5). By comparison, the role of NHE1 in epithelial function remains poorly understood. In particular, the contributions of NHE1 to transcellular acid-base transport and the possible mechanisms involved are largely undefined.

The medullary thick ascending limb (MTAL) of the mammalian kidney

participates in acid-base regulation by reabsorbing most of the filtered

not reabsorbed by the proximal

tubule (8,

9). Absorption of

not reabsorbed by the proximal

tubule (8,

9). Absorption of

by the MTAL depends on

H+ secretion mediated by the apical membrane NHE3

Na+/H+ exchanger

(8,

10–13)

and basolateral

by the MTAL depends on

H+ secretion mediated by the apical membrane NHE3

Na+/H+ exchanger

(8,

10–13)

and basolateral  efflux, which

involves Cl-/

efflux, which

involves Cl-/ exchange

(14). The MTAL also expresses

basolateral NHE1, and we have recently identified a novel role for this

exchanger in transepithelial

exchange

(14). The MTAL also expresses

basolateral NHE1, and we have recently identified a novel role for this

exchanger in transepithelial  absorption. Inhibition of NHE1 with amiloride or nerve growth factor (NGF) or

by NHE1 knock-out results secondarily in inhibition of apical NHE3, thereby

decreasing

absorption. Inhibition of NHE1 with amiloride or nerve growth factor (NGF) or

by NHE1 knock-out results secondarily in inhibition of apical NHE3, thereby

decreasing  absorption

(15–17).

NHE1 modulates NHE3 activity by regulating the organization of the actin

cytoskeleton (18). The rate of

luminal H+ secretion and transepithelial

absorption

(15–17).

NHE1 modulates NHE3 activity by regulating the organization of the actin

cytoskeleton (18). The rate of

luminal H+ secretion and transepithelial

absorption in the MTAL thus

depends on a regulatory interaction between the basolateral and apical

membrane Na+/H+ exchangers, whereby basolateral NHE1

enhances the activity of apical NHE3

(15–18).

absorption in the MTAL thus

depends on a regulatory interaction between the basolateral and apical

membrane Na+/H+ exchangers, whereby basolateral NHE1

enhances the activity of apical NHE3

(15–18).

Based on the above findings, a key to understanding the role of NHE1 in

epithelial function lies in identifying cell signals that modify transcellular

acid transport through effects on basolateral NHE1 activity. Recently we

demonstrated that NGF inhibits  absorption in the MTAL by inhibiting NHE1 through activation of the

extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway

(19). However, blocking ERK

activation eliminated only ∼50% of the NGF-induced transport regulation

(19). Thus, an additional

signaling pathway must play a role in mediating the inhibition of NHE1 by

NGF.

absorption in the MTAL by inhibiting NHE1 through activation of the

extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway

(19). However, blocking ERK

activation eliminated only ∼50% of the NGF-induced transport regulation

(19). Thus, an additional

signaling pathway must play a role in mediating the inhibition of NHE1 by

NGF.

The present study was designed to identify the signaling pathway

responsible for the remainder of NGF-induced inhibition of NHE1 and

absorption in the MTAL. We show

that NGF decreases

absorption in the MTAL. We show

that NGF decreases  absorption

through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-mammalian target of rapamycin

(mTOR)-dependent signaling pathway that functions in parallel with ERK to

inhibit NHE1. These studies identify a previously unrecognized role for mTOR

in regulating Na+/H+ exchange activity and the

absorptive function of renal tubules. The results implicate NHE1 as a possible

downstream effector contributing to mTOR's effects on cell growth,

proliferation, and tumorigenesis.

absorption

through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-mammalian target of rapamycin

(mTOR)-dependent signaling pathway that functions in parallel with ERK to

inhibit NHE1. These studies identify a previously unrecognized role for mTOR

in regulating Na+/H+ exchange activity and the

absorptive function of renal tubules. The results implicate NHE1 as a possible

downstream effector contributing to mTOR's effects on cell growth,

proliferation, and tumorigenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tubule Perfusion and Measurement of Net

Absorption—MTALs from

male Sprague-Dawley rats (50–100 g body wt; Taconic, Germantown, NY)

were isolated and perfused in vitro as previously described

(16,

20). Tubules were dissected

from the inner stripe of the outer medulla at 10 °C in control bath

solution (see below), transferred to a bath chamber on the stage of an

inverted microscope, and mounted on concentric glass pipettes for perfusion at

37 °C. For

Absorption—MTALs from

male Sprague-Dawley rats (50–100 g body wt; Taconic, Germantown, NY)

were isolated and perfused in vitro as previously described

(16,

20). Tubules were dissected

from the inner stripe of the outer medulla at 10 °C in control bath

solution (see below), transferred to a bath chamber on the stage of an

inverted microscope, and mounted on concentric glass pipettes for perfusion at

37 °C. For  transport

experiments, the tubules were perfused and bathed in control solution that

contained 146 mm Na+, 4 mm K+, 122

mm Cl-, 25 mm

transport

experiments, the tubules were perfused and bathed in control solution that

contained 146 mm Na+, 4 mm K+, 122

mm Cl-, 25 mm

, 2.0 mm

Ca2+, 1.5 mm Mg2+, 2.0 mm

phosphate, 1.2 mm

, 2.0 mm

Ca2+, 1.5 mm Mg2+, 2.0 mm

phosphate, 1.2 mm  , 1.0

mm citrate, 2.0 mm lactate, and 5.5 mm

glucose (equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2, pH 7.45, at 37

°C). Bath solutions also contained 0.2% fatty acid-free bovine albumin.

Experimental agents were added to the bath solution as described under

“Results.” Solutions containing experimental agents were prepared

as described (19,

21). Equal concentrations of

vehicle were added to control solutions in all protocols.

, 1.0

mm citrate, 2.0 mm lactate, and 5.5 mm

glucose (equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2, pH 7.45, at 37

°C). Bath solutions also contained 0.2% fatty acid-free bovine albumin.

Experimental agents were added to the bath solution as described under

“Results.” Solutions containing experimental agents were prepared

as described (19,

21). Equal concentrations of

vehicle were added to control solutions in all protocols.

The protocol for study of transepithelial

absorption was as described

(16,

20). Tubules were equilibrated

for 20–30 min at 37 °C in the initial perfusion and bath solutions,

and the luminal flow rate (normalized per unit tubule length) was adjusted to

1.5–1.9 nl/min/mm. One to three 10-min tubule fluid samples were then

collected for each period (initial, experimental, and recovery). The tubules

were allowed to re-equilibrate for 5–10 min after an experimental agent

was added to or removed from the bath solution. The absolute rate of

absorption was as described

(16,

20). Tubules were equilibrated

for 20–30 min at 37 °C in the initial perfusion and bath solutions,

and the luminal flow rate (normalized per unit tubule length) was adjusted to

1.5–1.9 nl/min/mm. One to three 10-min tubule fluid samples were then

collected for each period (initial, experimental, and recovery). The tubules

were allowed to re-equilibrate for 5–10 min after an experimental agent

was added to or removed from the bath solution. The absolute rate of

absorption

(

absorption

( , pmol/min/mm) was calculated

from the luminal flow rate and the difference between total CO2

concentrations measured in perfused and collected fluids

(20). An average

, pmol/min/mm) was calculated

from the luminal flow rate and the difference between total CO2

concentrations measured in perfused and collected fluids

(20). An average

absorption rate was calculated for

each period studied in a given tubule. When repeat measurements were made at

the beginning and end of an experiment (initial and recovery periods), the

values were averaged. Single tubule values are presented in Figs.

1,

2,

3,

4 and

6. Mean values ± S.E.

(n = number of tubules) are presented under

“Results.”

absorption rate was calculated for

each period studied in a given tubule. When repeat measurements were made at

the beginning and end of an experiment (initial and recovery periods), the

values were averaged. Single tubule values are presented in Figs.

1,

2,

3,

4 and

6. Mean values ± S.E.

(n = number of tubules) are presented under

“Results.”

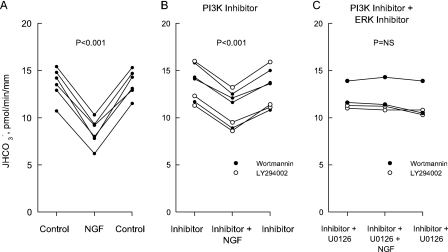

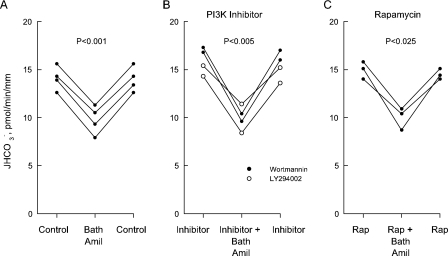

FIGURE 1.

Inhibition of  absorption by

NGF is reduced by PI3K inhibitors. Rat MTALs were isolated and

perfusedin vitroin control solution (A), bathed with 100

nm wortmannin or 20 μm LY294002 (B), or

bathed with a PI3K inhibitor plus the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 (15

μm) (C). NGF (0.7 nm) was then added to and

removed from the bath solution. Data points are average values for single

tubules. Lines connect paired measurements made in the same tubule.

p values are for paired t tests. NS, not

significant.

absorption by

NGF is reduced by PI3K inhibitors. Rat MTALs were isolated and

perfusedin vitroin control solution (A), bathed with 100

nm wortmannin or 20 μm LY294002 (B), or

bathed with a PI3K inhibitor plus the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 (15

μm) (C). NGF (0.7 nm) was then added to and

removed from the bath solution. Data points are average values for single

tubules. Lines connect paired measurements made in the same tubule.

p values are for paired t tests. NS, not

significant.  , absolute rate of

, absolute rate of

absorption. Mean values are given

under “Results.”

absorption. Mean values are given

under “Results.”

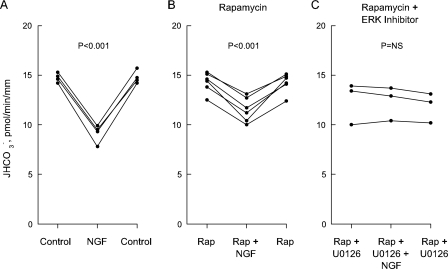

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of  absorption by

NGF is reduced by rapamycin. MTALs were studied in control solution

(A), bathed with 20 nm rapamycin (Rap,

B), or bathed with rapamycin + 15 μm U0126

(C). NGF (0.7 nm) was then added to and removed from the

bath solution.

absorption by

NGF is reduced by rapamycin. MTALs were studied in control solution

(A), bathed with 20 nm rapamycin (Rap,

B), or bathed with rapamycin + 15 μm U0126

(C). NGF (0.7 nm) was then added to and removed from the

bath solution.  , data points,

lines, and p values are as in Fig.

1. Mean values are given under “Results.”

, data points,

lines, and p values are as in Fig.

1. Mean values are given under “Results.”

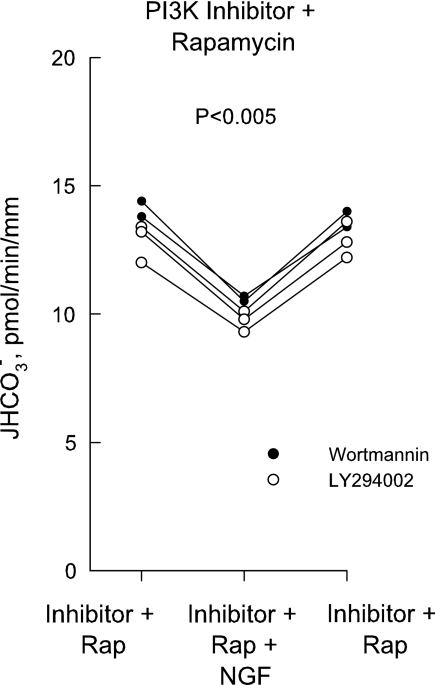

FIGURE 3.

Effect of PI3K inhibitors plus rapamycin on inhibition of

absorption by NGF. MTALs were

bathed with wortmannin (100 nm) or LY294002 (20 μm) +

rapamycin (Rap, 20 nm), and then NGF (0.7 nm)

was added to and removed from the bath solution.

absorption by NGF. MTALs were

bathed with wortmannin (100 nm) or LY294002 (20 μm) +

rapamycin (Rap, 20 nm), and then NGF (0.7 nm)

was added to and removed from the bath solution.

, data points, lines, and

p values are as in Fig.

1. Mean values are given under “Results.”

, data points, lines, and

p values are as in Fig.

1. Mean values are given under “Results.”

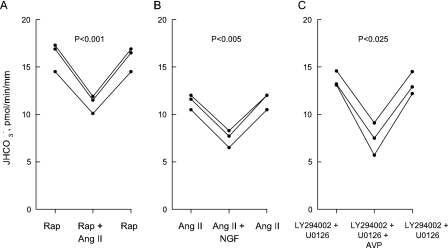

FIGURE 4.

Specificity of inhibitors in regulation of

absorption. A, MTALs

were bathed with rapamycin (Rap, 20 nm), and then

angiotensin II (Ang II, 10 nm) was added to and removed

from the bath solution. B, MTALs were bathed with angiotensin II (10

nm), and then NGF (0.7 nm) was added to and removed from

the bath solution. C, MTALs were bathed with LY294002 (20

μm) + U0126 (15 μm), and then arginine vasopressin

(AVP, 0.1 nm) was added to and removed from the bath

solution.

absorption. A, MTALs

were bathed with rapamycin (Rap, 20 nm), and then

angiotensin II (Ang II, 10 nm) was added to and removed

from the bath solution. B, MTALs were bathed with angiotensin II (10

nm), and then NGF (0.7 nm) was added to and removed from

the bath solution. C, MTALs were bathed with LY294002 (20

μm) + U0126 (15 μm), and then arginine vasopressin

(AVP, 0.1 nm) was added to and removed from the bath

solution.  , data points, lines,

and p values are as in Fig.

1. Mean values are given under “Results.”

, data points, lines,

and p values are as in Fig.

1. Mean values are given under “Results.”

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of  absorption by

bath amiloride is not affected by PI3K inhibitors or rapamycin. MTALs were

studied in control solution (A), bathed with 100 nm

wortmannin or 20 μm LY294002 (B), or bathed with 20

nm rapamycin (Rap, C). Amiloride (Amil,

10 μm) was then added to and removed from the bath solution.

absorption by

bath amiloride is not affected by PI3K inhibitors or rapamycin. MTALs were

studied in control solution (A), bathed with 100 nm

wortmannin or 20 μm LY294002 (B), or bathed with 20

nm rapamycin (Rap, C). Amiloride (Amil,

10 μm) was then added to and removed from the bath solution.

, data points, lines, and

p values are as in Fig.

1. Mean values are given under “Results.”

, data points, lines, and

p values are as in Fig.

1. Mean values are given under “Results.”

Measurement of Intracellular pH (pHi) and Basolateral

Na+/H+ Exchange

Activity—pHi was measured in isolated, perfused

MTALs by use of the pH-sensitive dye BCECF

(2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein) as described

(16,

22). For

pHi experiments, tubules were perfused and bathed in

Na+-free HEPES-buffered solution that contained 145 mm

N-methyl-d-glucammonium, 4 mm K+,

147 mm Cl-, 2.0 mm Ca2+, 1.5

mm Mg2+, 1.0 mm phosphate, 1.0 mm

, 1.0 mm citrate, 2.0

mm lactate, 5.5 mm glucose, and 5 mm HEPES

(equilibrated with 100% O2; titrated to pH 7.4). Basolateral

Na+/H+ exchange activity was determined by measurement

of the initial rate of pHi increase after the addition of

145 mm Na+ to the bath solution (Na+ replaced

N-methyl-d-glucammonium), the intracellular buffering

power, and cell volume as described

(16,

19). Interruption of

pHi recovery at various points along the recovery curve

permits determination of the Na+/H+ exchange rate over a

range of pHi values, with appropriate corrections for a

variable background acid loading rate

(16,

22). The

Na+-dependent pHi recovery rate was inhibited

≥90% by bath ethylisopropyl amiloride (50 μm) under all

experimental conditions.

, 1.0 mm citrate, 2.0

mm lactate, 5.5 mm glucose, and 5 mm HEPES

(equilibrated with 100% O2; titrated to pH 7.4). Basolateral

Na+/H+ exchange activity was determined by measurement

of the initial rate of pHi increase after the addition of

145 mm Na+ to the bath solution (Na+ replaced

N-methyl-d-glucammonium), the intracellular buffering

power, and cell volume as described

(16,

19). Interruption of

pHi recovery at various points along the recovery curve

permits determination of the Na+/H+ exchange rate over a

range of pHi values, with appropriate corrections for a

variable background acid loading rate

(16,

22). The

Na+-dependent pHi recovery rate was inhibited

≥90% by bath ethylisopropyl amiloride (50 μm) under all

experimental conditions.

Inner Stripe Tissue Preparation and Immunoblotting—The inner

stripe tissue preparation used to study signaling proteins has been previously

described (19,

21,

23). In brief, thin strips of

tissue were microdissected at 10 °C from the inner stripe of the outer

medulla, the region of the kidney highly enriched in MTALs. The tissue strips

were then divided into four samples of equal amount and incubated in

vitro at 37 °C in the same solutions used for

transport experiments

(19,

21,

23). The specific protocols

used for incubations are given under “Results” (Figs.

7 and

9D). After incubation,

the tissue was resuspended in ice-cold modified radioimmune precipitation

assay lysis buffer, pH 7.5, plus 1 mm NaF, 1 mm

Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride,

and protease inhibitor mixture (1:400; Sigma), homogenized, and lysed for 4 h

at 4 °C. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (4000 × g

for 10 min), and supernatants were separated into aliquots and stored at -80

°C. Samples of equal protein content were separated by SDS-PAGE on 8 or

10% gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes

were blocked with Tris-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween 20 + 1–5% bovine

serum albumin at 4 °C and incubated overnight at 4 °C with

antiphospho-Akt-Ser-473 (1:1000) or anti-Akt (1:2500) antibodies (Cell

Signaling Technology), or with antiphospho-mTOR-Ser-2448 (1:500; BIOSOURCE) or

anti-mTOR (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. After washing in

Tris-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween 20, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody was applied, and immunoreactive bands were

detected by chemiluminescence (Luminol Reagent, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Band intensities were quantified by densitometry.

transport experiments

(19,

21,

23). The specific protocols

used for incubations are given under “Results” (Figs.

7 and

9D). After incubation,

the tissue was resuspended in ice-cold modified radioimmune precipitation

assay lysis buffer, pH 7.5, plus 1 mm NaF, 1 mm

Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride,

and protease inhibitor mixture (1:400; Sigma), homogenized, and lysed for 4 h

at 4 °C. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (4000 × g

for 10 min), and supernatants were separated into aliquots and stored at -80

°C. Samples of equal protein content were separated by SDS-PAGE on 8 or

10% gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes

were blocked with Tris-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween 20 + 1–5% bovine

serum albumin at 4 °C and incubated overnight at 4 °C with

antiphospho-Akt-Ser-473 (1:1000) or anti-Akt (1:2500) antibodies (Cell

Signaling Technology), or with antiphospho-mTOR-Ser-2448 (1:500; BIOSOURCE) or

anti-mTOR (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. After washing in

Tris-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween 20, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody was applied, and immunoreactive bands were

detected by chemiluminescence (Luminol Reagent, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Band intensities were quantified by densitometry.

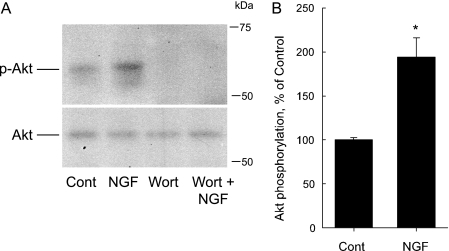

FIGURE 7.

NGF increases Akt phosphorylation. A, inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro at 37 °C in the absence (Cont) and presence of 100 nm wortmannin (Wort) for 15 min, then treated with 0.7 nm NGF for 15 min. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antiphospho-Akt-Ser-473 antibody (p-Akt) to analyze Akt phosphorylation and anti-Akt antibody for total Akt level. Data are representative of three independent experiments. B, phosphorylated Akt was analyzed by densitometry and presented as a percentage of the control level measured in the same experiment. Bars are means ± S.E. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 versus Control.

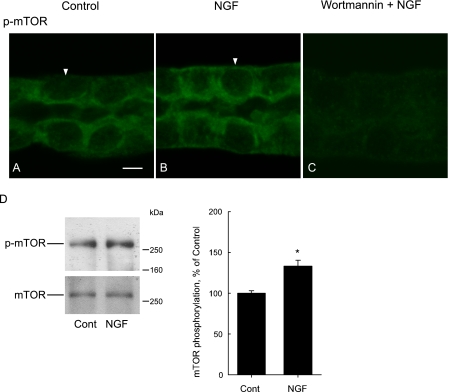

FIGURE 9.

NGF increases p-mTOR labeling in the basolateral membrane domain. A–C, MTALs were incubated in vitro in control solution (A), 0.7 nm NGF (B), or 100 nm wortmannin + NGF (C) for 15 min, then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with antiphospho-mTOR-Ser-2448 antibody (p-mTOR). Tubules were analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Images are z-axis sections (<0.4 μm) taken through a plane at the center of the tubule showing a cross-sectional view of cells in the lateral tubule walls (18). NGF increased p-mTOR labeling in the basolateral membrane domain (arrowheads). Quantification of membrane fluorescence intensity is given under “Results.” Images are representative of five independent experiments. Bar, 5 μm. D, inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro at 37 °C in the absence (Cont) and presence of 0.7 nm NGF for 15 min. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antiphospho-mTOR-Ser-2448 (p-mTOR) and anti-mTOR (mTOR) antibodies. Blots are representative of three separate experiments. Bars show densitometric analysis of mTOR phosphorylation, presented as a percentage of the control level measured in the same experiment. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 versus control.

p70 S6 Kinase (S6K) Assay—Inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro at 37 °C in the absence and presence of NGF and various inhibitors, and cell lysates were prepared as described above. The specific incubation conditions are indicated under “Results” (Fig. 8). For immunoprecipitation, equal amounts of sample protein (500 μg) were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with 4 μg of rabbit anti-p70 S6K antibody (Upstate Biotechnology) coupled to protein A/G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz). The immune complexes were then washed 3 times in Triton X-100 lysis buffer and one time in assay dilution buffer (20 mm MOPS, pH 7.2, 25 mm sodium β-glycerophosphate, 5 mm EGTA, 1 mm Na3VO4, and 1 mm dithiothreitol). Kinase activity in immunoprecipitates was measured using a p70 S6K assay kit (Upstate). In brief, immunoprecipitates were incubated for 15 min at 30 °C in 50 μl final volume of assay dilution buffer containing 5 μm S6K substrate peptide 2 (KKRNRTLTK), inhibitor mixture containing protein kinase C and A and CdK inhibitors, magnesium acetate/ATP mixture, and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. Sample aliquots (25 μl) were then spotted onto P81 phosphocellulose paper. The paper was washed 5 times with 0.75% phosphoric acid and 1 time with acetone, and phosphorylated substrate was quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Results were corrected for background determined in each experiment by a negative control assay in which endogenous peptide substrate was omitted from the reaction mixture. Experimental values are presented as a percentage of the control value measured in the same experiment. Equal amounts of S6K in immunoprecipitates were verified within experiments by immunoblotting. We have demonstrated previously that changes in kinase activities measured in the inner stripe preparation reproduce accurately changes measured in the MTAL (19, 21, 23, 24).

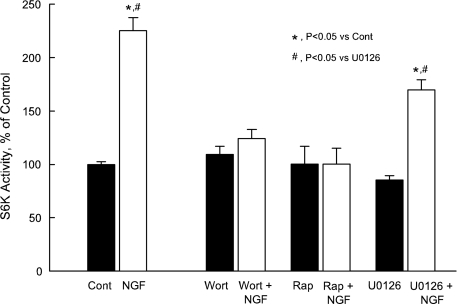

FIGURE 8.

NGF increases S6K activity. Inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro at 37 °C in the absence (Cont) and presence of 100 nm wortmannin (Wort), 20 nm rapamycin (Rap), or 15 μm U0126 for 15 min, then treated with 0.7 nm NGF for 15 min. S6K was immunoprecipitated, and in vitro kinase activity determined by phosphorylation of S6 peptide substrate (see “Experimental Procedures”). Phosphorylated products were spotted onto phosphocellulose paper and quantified by scintillation counting. Phosphotransferase activity of S6K is presented as a percentage of control activity measured in the same experiment. Bars are means ± S.E. for five independent experiments.

Confocal Immunofluorescence Microscopy—MTALs were studied by

confocal microscopy as previously described

(18). MTALs were

microdissected and mounted on Cell-Tak-coated coverslips at 10 °C. The

tubules were then incubated in the absence and presence of NGF for 15 min at

37 °C in a flowing bath using the same solutions as in

transport experiments. After

incubation, the tubules were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS),

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, and permeabilized with 0.3%

Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. The tubules were incubated in Image-iT FX

signal enhancer (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature, washed, and

blocked in phosphate-buffered saline + 0.25% Tween 20 + 10% normal goat serum

for 1 h at room temperature. The tubules were then incubated overnight at 4

°C with a 1:50 dilution of antiphospho-mTOR-Ser-2448 antibody, washed, and

then incubated for 1 h at room temperature in Alexa 488-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:100; Invitrogen). Fluorescence staining was

examined in the UTMB Optical Imaging Core using a Zeiss laser-scanning

confocal microscope (LSM 510 UV META) as described

(18). Tubules were imaged

longitudinally, and z-axis optical sections (<0.4 μm) were

obtained through a plane at the center of the tubule, which provides a

cross-sectional view of cells in the lateral tubule walls

(18). For individual

experiments, two to four tubules from the same kidney for each experimental

condition were fixed and stained identically and imaged in a single session at

identical settings of illumination, gain, and exposure time. Two-dimensional

image analysis was performed using MetaMorph software in which boxes (4.5

× 1.2 μm) were positioned on linear regions of basolateral and apical

membrane domains, and pixel intensity per unit area was determined for each

region. Two to four cells were analyzed in each tubule, and the values were

averaged. Fluorescence intensity for NGF-treated tubules was expressed as a

percentage of the control value measured in the same experiment.

transport experiments. After

incubation, the tubules were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS),

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, and permeabilized with 0.3%

Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. The tubules were incubated in Image-iT FX

signal enhancer (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature, washed, and

blocked in phosphate-buffered saline + 0.25% Tween 20 + 10% normal goat serum

for 1 h at room temperature. The tubules were then incubated overnight at 4

°C with a 1:50 dilution of antiphospho-mTOR-Ser-2448 antibody, washed, and

then incubated for 1 h at room temperature in Alexa 488-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:100; Invitrogen). Fluorescence staining was

examined in the UTMB Optical Imaging Core using a Zeiss laser-scanning

confocal microscope (LSM 510 UV META) as described

(18). Tubules were imaged

longitudinally, and z-axis optical sections (<0.4 μm) were

obtained through a plane at the center of the tubule, which provides a

cross-sectional view of cells in the lateral tubule walls

(18). For individual

experiments, two to four tubules from the same kidney for each experimental

condition were fixed and stained identically and imaged in a single session at

identical settings of illumination, gain, and exposure time. Two-dimensional

image analysis was performed using MetaMorph software in which boxes (4.5

× 1.2 μm) were positioned on linear regions of basolateral and apical

membrane domains, and pixel intensity per unit area was determined for each

region. Two to four cells were analyzed in each tubule, and the values were

averaged. Fluorescence intensity for NGF-treated tubules was expressed as a

percentage of the control value measured in the same experiment.

RESULTS

PI3K Inhibitors Reduce Inhibition of

Absorption by NGF—Under

control conditions, adding 0.7 nm NGF to the bath decreased

Absorption by NGF—Under

control conditions, adding 0.7 nm NGF to the bath decreased

absorption in isolated MTALs by

39%, from 13.7 ± 0.6 to 8.4 ± 0.6 pmol/min/mm

(Fig. 1A). In MTALs

bathed with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (100 nm) or LY294002 (20

μm), NGF decreased

absorption in isolated MTALs by

39%, from 13.7 ± 0.6 to 8.4 ± 0.6 pmol/min/mm

(Fig. 1A). In MTALs

bathed with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (100 nm) or LY294002 (20

μm), NGF decreased  absorption only by 21%, from 13.5 ± 0.8 to 10.6 ± 0.7

pmol/min/mm (Fig. 1B).

The net decrease in

absorption only by 21%, from 13.5 ± 0.8 to 10.6 ± 0.7

pmol/min/mm (Fig. 1B).

The net decrease in  absorption

induced by NGF was reduced 45% by the PI3K inhibitors (5.3 ± 0.3

pmol/min/mm without inhibitors versus 2.9 ± 0.3 pmol/min/mm

with inhibitors; p < 0.001). In previous studies, inhibition of

absorption

induced by NGF was reduced 45% by the PI3K inhibitors (5.3 ± 0.3

pmol/min/mm without inhibitors versus 2.9 ± 0.3 pmol/min/mm

with inhibitors; p < 0.001). In previous studies, inhibition of

absorption by NGF was reduced

50–60% by inhibitors of ERK activation

(19). As shown in

Fig. 1C, the

combination of a PI3K inhibitor plus a MEK/ERK inhibitor (U0126) completely

eliminated the inhibition by NGF, indicating that the inhibitory effects of

PI3K and ERK are additive. These results support the view that NGF inhibits

absorption by NGF was reduced

50–60% by inhibitors of ERK activation

(19). As shown in

Fig. 1C, the

combination of a PI3K inhibitor plus a MEK/ERK inhibitor (U0126) completely

eliminated the inhibition by NGF, indicating that the inhibitory effects of

PI3K and ERK are additive. These results support the view that NGF inhibits

absorption through the parallel

activation of PI3K- and ERK-dependent signaling pathways.

absorption through the parallel

activation of PI3K- and ERK-dependent signaling pathways.

Rapamycin Reduces Inhibition of

Absorption by NGF—An

important downstream effector of PI3K in growth factor signaling is mTOR,

which is specifically inhibited by the immunosuppressive drug rapamycin

(25). Similar to the preceding

results with PI3K inhibitors, NGF decreased

Absorption by NGF—An

important downstream effector of PI3K in growth factor signaling is mTOR,

which is specifically inhibited by the immunosuppressive drug rapamycin

(25). Similar to the preceding

results with PI3K inhibitors, NGF decreased

absorption by 38% under control

conditions (from 14.8 ± 0.4 to 9.2 ± 0.5 pmol/min/mm) but only

by 19% (from 14.3 ± 0.4 to 11.6 ± 0.6 pmol/min/mm) in MTALs

bathed with 20 nm rapamycin

(Fig. 2, A and

B). The net decrease in

absorption by 38% under control

conditions (from 14.8 ± 0.4 to 9.2 ± 0.5 pmol/min/mm) but only

by 19% (from 14.3 ± 0.4 to 11.6 ± 0.6 pmol/min/mm) in MTALs

bathed with 20 nm rapamycin

(Fig. 2, A and

B). The net decrease in

absorption induced by NGF was

reduced 50% by rapamycin (p < 0.001). The combination of rapamycin

plus U0126 again completely eliminated the inhibition by NGF

(Fig. 2C). These

results support a role for mTOR in mediating the inhibition of

absorption induced by NGF was

reduced 50% by rapamycin (p < 0.001). The combination of rapamycin

plus U0126 again completely eliminated the inhibition by NGF

(Fig. 2C). These

results support a role for mTOR in mediating the inhibition of

absorption by NGF and show that

inhibition via the rapamycin-sensitive pathway is additive to inhibition

mediated through ERK.

absorption by NGF and show that

inhibition via the rapamycin-sensitive pathway is additive to inhibition

mediated through ERK.

Effects of PI3K Inhibitors and Rapamycin Are Not

Additive—Because PI3K inhibitors and rapamycin reduced the

inhibition of  absorption by NGF by

a similar amount, further experiments were carried out to test whether these

agents block a common pathway. In MTALs bathed with a PI3K inhibitor plus

rapamycin, NGF decreased

absorption by NGF by

a similar amount, further experiments were carried out to test whether these

agents block a common pathway. In MTALs bathed with a PI3K inhibitor plus

rapamycin, NGF decreased  absorption by 22%, from 13.4 ± 0.3 to 10.4 ± 0.1 pmol/min/mm

(Fig. 3), a decrease similar to

that observed with either inhibitor alone (Figs.

1B and

2B). Thus, combining a

PI3K inhibitor with rapamycin does not cause a further reduction in the

inhibition by NGF, consistent with these agents blocking a common regulatory

pathway. These results support the view that PI3K and mTOR are components of a

common signaling pathway that inhibits

absorption by 22%, from 13.4 ± 0.3 to 10.4 ± 0.1 pmol/min/mm

(Fig. 3), a decrease similar to

that observed with either inhibitor alone (Figs.

1B and

2B). Thus, combining a

PI3K inhibitor with rapamycin does not cause a further reduction in the

inhibition by NGF, consistent with these agents blocking a common regulatory

pathway. These results support the view that PI3K and mTOR are components of a

common signaling pathway that inhibits

absorption.

absorption.

Specificity of Inhibitors in Regulation of

Absorption—To assess

the specificity of rapamycin actions on

Absorption—To assess

the specificity of rapamycin actions on

absorption, we examined factors

that inhibit

absorption, we examined factors

that inhibit  absorption through

signaling pathways not involving PI3K. Angiotensin II inhibits

absorption through

signaling pathways not involving PI3K. Angiotensin II inhibits

absorption in the MTAL through

cytochrome P450 (26). In MTALs

bathed with rapamycin, angiotensin II decreased

absorption in the MTAL through

cytochrome P450 (26). In MTALs

bathed with rapamycin, angiotensin II decreased

absorption by 32 ± 1%

(Fig. 4A), an effect

similar to that observed under identical conditions in the absence of the

inhibitor (26). In previous

studies we found that rapamycin also has no effect on inhibition of

absorption by 32 ± 1%

(Fig. 4A), an effect

similar to that observed under identical conditions in the absence of the

inhibitor (26). In previous

studies we found that rapamycin also has no effect on inhibition of

absorption by aldosterone, which

is mediated through ERK (24).

Thus, rapamycin selectively reduces inhibition of

absorption by aldosterone, which

is mediated through ERK (24).

Thus, rapamycin selectively reduces inhibition of

absorption by NGF that depends on

PI3K. Consistent with these findings, the inhibition of

absorption by NGF that depends on

PI3K. Consistent with these findings, the inhibition of

absorption by NGF is additive to

inhibition by angiotensin II (Fig.

4B) and aldosterone

(27), further confirming that

these factors act through distinct signaling pathways. Additional experiments

evaluated the specificity of the PI3K inhibitor + ERK inhibitor combination by

examining arginine vasopressin, which inhibits

absorption by NGF is additive to

inhibition by angiotensin II (Fig.

4B) and aldosterone

(27), further confirming that

these factors act through distinct signaling pathways. Additional experiments

evaluated the specificity of the PI3K inhibitor + ERK inhibitor combination by

examining arginine vasopressin, which inhibits

absorption via cAMP

(20). In MTALs bathed with

LY294002 plus U0126, vasopressin decreased

absorption via cAMP

(20). In MTALs bathed with

LY294002 plus U0126, vasopressin decreased

absorption by 45 ± 5%

(Fig. 4C), an effect

similar to that observed in the absence of the inhibitors

(20). Thus, the effect of the

PI3K-ERK inhibitor combination to eliminate inhibition of

absorption by 45 ± 5%

(Fig. 4C), an effect

similar to that observed in the absence of the inhibitors

(20). Thus, the effect of the

PI3K-ERK inhibitor combination to eliminate inhibition of

absorption is selective for NGF

(Fig. 1C) and is not

the result of nonspecific metabolic or cytotoxic effects on the tubule

cells.

absorption is selective for NGF

(Fig. 1C) and is not

the result of nonspecific metabolic or cytotoxic effects on the tubule

cells.

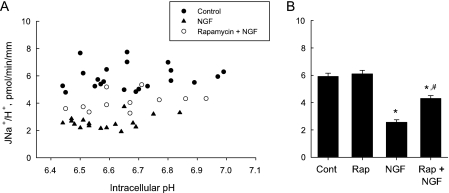

Rapamycin Reduces Inhibition of Basolateral

Na+/H+ Exchange by NGF—In

the MTAL, NGF decreases  absorption

through primary inhibition of the basolateral NHE1

Na+/H+ exchanger

(16,

17). To determine whether the

PI3K-mTOR pathway is involved in mediating inhibition of basolateral

Na+/H+ exchange, we examined the effects of NGF in the

absence and presence of rapamycin. Under control conditions, NGF decreased

basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity at all

pHi values studied (control versus NGF;

Fig. 5A). In MTALs

bathed with rapamycin, the inhibition by NGF was significantly reduced

(rapamycin + NGF, Fig.

5A). Overall, the net decrease in basolateral

Na+/H+ exchange activity induced by NGF was reduced 45%

by rapamycin (p < 0.05; Fig.

5B). Rapamycin alone did not affect basolateral

Na+/H+ exchange activity

(Fig. 5B). These

results demonstrate that NGF inhibits basolateral Na+/H+

exchange via a rapamycin-sensitive pathway and are consistent with mTOR acting

downstream of PI3K to mediate NGF-induced inhibition of NHE1 and

absorption

through primary inhibition of the basolateral NHE1

Na+/H+ exchanger

(16,

17). To determine whether the

PI3K-mTOR pathway is involved in mediating inhibition of basolateral

Na+/H+ exchange, we examined the effects of NGF in the

absence and presence of rapamycin. Under control conditions, NGF decreased

basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity at all

pHi values studied (control versus NGF;

Fig. 5A). In MTALs

bathed with rapamycin, the inhibition by NGF was significantly reduced

(rapamycin + NGF, Fig.

5A). Overall, the net decrease in basolateral

Na+/H+ exchange activity induced by NGF was reduced 45%

by rapamycin (p < 0.05; Fig.

5B). Rapamycin alone did not affect basolateral

Na+/H+ exchange activity

(Fig. 5B). These

results demonstrate that NGF inhibits basolateral Na+/H+

exchange via a rapamycin-sensitive pathway and are consistent with mTOR acting

downstream of PI3K to mediate NGF-induced inhibition of NHE1 and

absorption.

absorption.

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of basolateral Na+/H+ exchange by NGF is reduced by rapamycin. A, MTALs were studied under control conditions and with NGF (0.7 nm) or NGF + rapamycin (Rap, 20 nm) in the bath solution. Basolateral Na+/H+ exchange rates (JNa+/H+) were determined at various pHi values from initial rates of pHi increase after the addition of Na+ to the bath solution (see “Experimental Procedures”). Data points are from 11 control tubules, 11 tubules with NGF, and 7 tubules with rapamycin + NGF. B, mean basolateral Na+/H+ exchange rates for the three conditions in panel A plus additional data from seven tubules studied with rapamycin alone. *, p < 0.05 versus control or rapamycin; #, p < 0.05 versus NGF (analysis of variance).

PI3K Inhibitors and Rapamycin Do Not Affect Inhibition By Bath

Amiloride—Inhibiting basolateral Na+/H+

exchange decreases  absorption in

the MTAL by inducing actin cytoskeleton remodeling that secondarily inhibits

apical Na+/H+ exchange

(18). Thus, an additional

mechanism through which PI3K-mTOR signaling could affect

absorption in

the MTAL by inducing actin cytoskeleton remodeling that secondarily inhibits

apical Na+/H+ exchange

(18). Thus, an additional

mechanism through which PI3K-mTOR signaling could affect

absorption is by modifying the

regulatory interaction between basolateral and apical

Na+/H+ exchangers. To test this, we took advantage of

our previous finding that the interaction between exchangers and the resulting

inhibition of

absorption is by modifying the

regulatory interaction between basolateral and apical

Na+/H+ exchangers. To test this, we took advantage of

our previous finding that the interaction between exchangers and the resulting

inhibition of  absorption can be

induced directly by inhibiting basolateral NHE1 with bath amiloride

(16–18).

Under control conditions, the addition of 10 μm amiloride to the

bath decreased

absorption can be

induced directly by inhibiting basolateral NHE1 with bath amiloride

(16–18).

Under control conditions, the addition of 10 μm amiloride to the

bath decreased  absorption by 31%,

from 14.1 ± 0.6 to 9.7 ± 0.7 pmol/min/mm

(Fig. 6A). This

inhibition was not affected by either PI3K inhibitors

(Fig. 6B) or rapamycin

(Fig. 6C). These

results indicate that PI3K and mTOR are not involved in mediating the

regulatory interaction between the basolateral NHE1 and apical NHE3

Na+/H+ exchangers. Taken together, our findings indicate

that the role of the PI3K-mTOR pathway in inhibition of

absorption by 31%,

from 14.1 ± 0.6 to 9.7 ± 0.7 pmol/min/mm

(Fig. 6A). This

inhibition was not affected by either PI3K inhibitors

(Fig. 6B) or rapamycin

(Fig. 6C). These

results indicate that PI3K and mTOR are not involved in mediating the

regulatory interaction between the basolateral NHE1 and apical NHE3

Na+/H+ exchangers. Taken together, our findings indicate

that the role of the PI3K-mTOR pathway in inhibition of

absorption is to mediate the

effect of NGF to decrease basolateral Na+/H+ exchange

activity.

absorption is to mediate the

effect of NGF to decrease basolateral Na+/H+ exchange

activity.

NGF Activates Akt and S6K—Further studies were carried out

to examine the effects of NGF on additional signaling components in the

PI3K-mTOR pathway. The serine/threonine kinase Akt is a downstream target of

PI3K that links PI3K to activation of mTOR

(25). To test whether NGF

activates Akt, inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro in the

absence and presence of NGF for 15 min, and Akt phosphorylation was analyzed

by immunoblotting using antiphospho-Akt-Ser-473 antibody. As shown in

Fig. 7, NGF increased Akt

phosphorylation 2-fold without a change in total Akt expression. The

phosphorylation of Akt was blocked by wortmannin

(Fig. 7A), consistent

with a requirement for PI3K in the NGF-induced Akt activation. These results

are consistent with a role for Akt in mediating PI3K-dependent inhibition of

absorption in the MTAL.

absorption in the MTAL.

In contrast to Akt, which functions as an upstream activator of mTOR, S6K

is an important downstream effector of mTOR

(25). To test the effect of

NGF on S6K, inner stripe tissue was exposed to NGF in vitro for 15

min, and S6K activity was measured by immune complex assay. As shown in

Fig. 8, NGF increased S6K

activity 2.2-fold. This activation was blocked by wortmannin or rapamycin,

consistent with PI3K, mTOR, and S6K in a linear signaling pathway. In

contrast, S6K activation was not blocked by the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126,

confirming further that activation of the PI3K-mTOR-S6K pathway by NGF occurs

independently of the activation of ERK. These results indicate that NGF

increases S6K activity via a PI3K- and mTOR-dependent pathway and suggest that

S6K may be a downstream effector of PI3K and mTOR in mediating NGF-induced

inhibition of NHE1 and  absorption

(see “Discussion”).

absorption

(see “Discussion”).

NGF Increases Phosphorylated mTOR Level in the Basolateral Membrane

Domain—The sensitivity to rapamycin (Figs.

2 and

5) suggests that the inhibition

of NHE1 and  absorption by NGF

depends on activation of mTOR. To verify mTOR regulation, we examined the

effects of NGF on the level and subcellular location of phosphorylated mTOR.

Microdissected MTALs were incubated in vitro in the absence and

presence of NGF for 15 min, stained with antiphospho-mTOR-Ser-2448 antibody

(p-mTOR), and then analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence. Phosphorylation of

mTOR at Ser-2448 correlates with growth factor stimulation of the

PI3K-mTOR-S6K pathway (28). In

control tubules, staining for p-mTOR was seen in the cytoplasm and along the

plasma membranes (Fig.

9A). Stimulation with NGF induced a clear increase in

p-mTOR labeling along the basolateral membrane domain

(Fig. 9B).

Two-dimensional image analysis (see “Experimental Procedures”)

showed that NGF increased the intensity of p-mTOR staining in the basolateral

membrane 1.5 ± 0.1-fold (n = 5; p < 0.05) with no

effect on signal intensity in the apical membrane (1.1 ± 0.1-fold;

p = NS). The phosphorylation of mTOR was inhibited by wortmannin

(Fig. 9C). The effect

of NGF on mTOR phosphorylation was examined further by immunoblot analysis of

inner stripe tissue. As shown in Fig.

9D, NGF increased mTOR phosphorylation 1.3-fold without a

change in total mTOR level. These results confirm NGF-induced regulation of

mTOR in the MTAL and show that the PI3K-mTOR-dependent inhibition of

basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity is associated with

an increased level of phosphorylated mTOR in the basolateral membrane

domain.

absorption by NGF

depends on activation of mTOR. To verify mTOR regulation, we examined the

effects of NGF on the level and subcellular location of phosphorylated mTOR.

Microdissected MTALs were incubated in vitro in the absence and

presence of NGF for 15 min, stained with antiphospho-mTOR-Ser-2448 antibody

(p-mTOR), and then analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence. Phosphorylation of

mTOR at Ser-2448 correlates with growth factor stimulation of the

PI3K-mTOR-S6K pathway (28). In

control tubules, staining for p-mTOR was seen in the cytoplasm and along the

plasma membranes (Fig.

9A). Stimulation with NGF induced a clear increase in

p-mTOR labeling along the basolateral membrane domain

(Fig. 9B).

Two-dimensional image analysis (see “Experimental Procedures”)

showed that NGF increased the intensity of p-mTOR staining in the basolateral

membrane 1.5 ± 0.1-fold (n = 5; p < 0.05) with no

effect on signal intensity in the apical membrane (1.1 ± 0.1-fold;

p = NS). The phosphorylation of mTOR was inhibited by wortmannin

(Fig. 9C). The effect

of NGF on mTOR phosphorylation was examined further by immunoblot analysis of

inner stripe tissue. As shown in Fig.

9D, NGF increased mTOR phosphorylation 1.3-fold without a

change in total mTOR level. These results confirm NGF-induced regulation of

mTOR in the MTAL and show that the PI3K-mTOR-dependent inhibition of

basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity is associated with

an increased level of phosphorylated mTOR in the basolateral membrane

domain.

DISCUSSION

Previously we identified a novel role for the basolateral NHE1

Na+/H+ exchanger in transepithelial

absorption in the renal MTAL

(15–17).

In the present study we examined the effects of NGF to identify signal

transduction pathways that regulate transcellular H+ secretion

through effects on NHE1 activity. The results reveal a new role for PI3K-mTOR

signaling in the acute regulation of NHE1 and provide the first evidence that

mTOR is involved in regulating the absorptive function of renal tubules.

absorption in the renal MTAL

(15–17).

In the present study we examined the effects of NGF to identify signal

transduction pathways that regulate transcellular H+ secretion

through effects on NHE1 activity. The results reveal a new role for PI3K-mTOR

signaling in the acute regulation of NHE1 and provide the first evidence that

mTOR is involved in regulating the absorptive function of renal tubules.

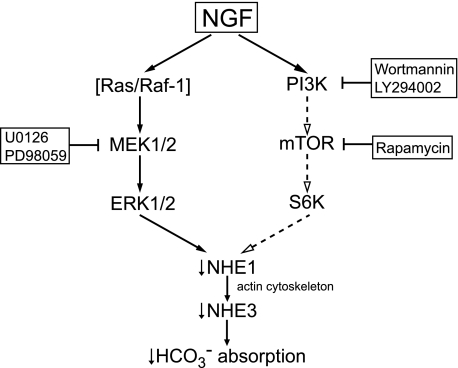

A model for NGF-induced regulation in the MTAL based on our current and

previous

(16–19)

findings is presented in Fig.

10. Binding of NGF to its basolateral cell surface receptor (TrkA)

induces parallel activation of PI3K and ERK signaling cascades. Activation of

PI3K leads to the downstream activation of Akt, mTOR, and S6K. The PI3K-mTOR

and ERK pathways converge to inhibit basolateral NHE1. This in turn induces

actin cytoskeleton remodeling that secondarily inhibits apical NHE3, resulting

in decreased luminal H+ secretion and transepithelial

absorption

(16,

18). The PI3K-mTOR and ERK

pathways function independently to inhibit NHE1, with each pathway accounting

for ∼50% of the NGF-induced transport inhibition.

absorption

(16,

18). The PI3K-mTOR and ERK

pathways function independently to inhibit NHE1, with each pathway accounting

for ∼50% of the NGF-induced transport inhibition.

FIGURE 10.

Model of signaling pathways mediating inhibition of NHE1 and

absorption by NGF in the MTAL.

NGF induces parallel activation of PI3K-mTOR and ERK signaling pathways, which

function independently to inhibit basolateral NHE1. Inhibition of NHE1 induces

actin cytoskeleton remodeling that secondarily inhibits apical NHE3, resulting

in decreased luminal H+ secretion and transepithelial

absorption by NGF in the MTAL.

NGF induces parallel activation of PI3K-mTOR and ERK signaling pathways, which

function independently to inhibit basolateral NHE1. Inhibition of NHE1 induces

actin cytoskeleton remodeling that secondarily inhibits apical NHE3, resulting

in decreased luminal H+ secretion and transepithelial

absorption. S6K is proposed to

function downstream of mTOR to inhibit NHE1. Regulatory steps linked by

arrows are not necessarily direct and may involve additional

signaling proteins.

absorption. S6K is proposed to

function downstream of mTOR to inhibit NHE1. Regulatory steps linked by

arrows are not necessarily direct and may involve additional

signaling proteins.

The role of NHE1 in processes such as proliferation and survival, adhesion

and migration, and the motile and invasive properties of tumor cells

(1–7)

has led to extensive investigation of cell signaling pathways that regulate

NHE1 activity. NHE1 is regulated by diverse stimuli acting through receptor

tyrosine kinases, G protein-coupled receptors, and integrin receptors

(2,

3). Activation of NHE1 in

response to growth factors and other stimuli involves phosphorylation of the

exchanger by various kinases, including the ERK-regulated kinase

p90RSK (29), the

RhoA target p160 Rho-associated kinase 1 (p160ROCK)

(30), and the serine/threonine

kinase Nck-interacting kinase (NIK)

(31). NHE1 also is modulated

through physical interactions with other regulatory proteins such as

Ca2+-calmodulin and calcineurin B homologous proteins (CHIPs)

(32–34).

A signaling molecule importantly involved in the control of cell growth,

proliferation, motility, and transformation is PI3K

(25,

35–37).

Although PI3K has been implicated in regulation of

Na+/H+ exchange activity in mammary epithelial cells and

breast tumor cells (38,

39), PI3K signaling generally

has not been ascribed a significant role in regulating NHE1 and its

physiological functions

(1–3,

5). In the present study we

demonstrate that PI3K plays a major role in NGF-induced inhibition of

absorption, mediated through

inhibition of NHE1. Thus, PI3K signaling is importantly involved in regulating

the epithelial function of NHE1 to control transcellular H+

secretion in MTAL cells. Of significance, we found that PI3K signaling

inhibits NHE1 activity, contrary to the stimulation of NHE1 by other

growth-related signaling pathways

(1–3).

It remains to be determined whether PI3K inhibits NHE1 in other epithelial or

nonepithelial cells or if this represents a specialized response of the MTAL.

It is conceivable that PI3K could function in a negative feedback or

compensatory pathway that serves to modulate the stimulation of NHE1 by other

mitogenic pathways. Such a system would be analogous to the role of PI3K-Akt

signaling in innate immune regulation, where it serves as a negative regulator

of immune receptor signaling to limit the magnitude of proinflammatory

responses that can lead to organ damage

(40,

41). Consistent with this

possibility, inhibiting PI3K potentiated activation of

Na+/H+ exchange that was responsible for increased

motility and invasion of breast epithelial tumor cells during serum

deprivation (39). These

results support a role for PI3K in suppressing NHE1 stimulation that leads to

tumor cell transformation and metastasis.

absorption, mediated through

inhibition of NHE1. Thus, PI3K signaling is importantly involved in regulating

the epithelial function of NHE1 to control transcellular H+

secretion in MTAL cells. Of significance, we found that PI3K signaling

inhibits NHE1 activity, contrary to the stimulation of NHE1 by other

growth-related signaling pathways

(1–3).

It remains to be determined whether PI3K inhibits NHE1 in other epithelial or

nonepithelial cells or if this represents a specialized response of the MTAL.

It is conceivable that PI3K could function in a negative feedback or

compensatory pathway that serves to modulate the stimulation of NHE1 by other

mitogenic pathways. Such a system would be analogous to the role of PI3K-Akt

signaling in innate immune regulation, where it serves as a negative regulator

of immune receptor signaling to limit the magnitude of proinflammatory

responses that can lead to organ damage

(40,

41). Consistent with this

possibility, inhibiting PI3K potentiated activation of

Na+/H+ exchange that was responsible for increased

motility and invasion of breast epithelial tumor cells during serum

deprivation (39). These

results support a role for PI3K in suppressing NHE1 stimulation that leads to

tumor cell transformation and metastasis.

mTOR plays a central role in the control of cell growth, survival, and

proliferation, with abnormal elevation of PI3K-mTOR signaling a contributing

factor in tumorigenesis (25,

37,

42). To our knowledge, no

previous studies have reported a role for mTOR in the regulation of

Na+/H+ exchange activity. Results of the present study

indicate that mTOR functions downstream of PI3K to mediate NGF-induced

inhibition of NHE1 and  absorption.

This conclusion is supported by several lines of evidence. 1) Inhibition of

absorption.

This conclusion is supported by several lines of evidence. 1) Inhibition of

absorption by NGF was reduced by

wortmannin or LY294002, two chemically unrelated PI3K inhibitors with

different mechanisms of action shown previously to block PI3K-dependent

transport regulation in the MTAL

(21). Wortmannin was studied

at a concentration that selectively inhibits PI3K, with no significant effects

against mTOR, other PI3K-related kinases, and a broad range of protein kinases

(43–45).

2) NGF increased wortmannin-sensitive phosphorylation of the PI3K substrate

Akt, confirming PI3K activation. 3) Inhibition of NHE1 and

absorption by NGF was reduced by

wortmannin or LY294002, two chemically unrelated PI3K inhibitors with

different mechanisms of action shown previously to block PI3K-dependent

transport regulation in the MTAL

(21). Wortmannin was studied

at a concentration that selectively inhibits PI3K, with no significant effects

against mTOR, other PI3K-related kinases, and a broad range of protein kinases

(43–45).

2) NGF increased wortmannin-sensitive phosphorylation of the PI3K substrate

Akt, confirming PI3K activation. 3) Inhibition of NHE1 and

absorption were reduced by

rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTOR signaling (see below). 4) The effects

of PI3K inhibitors and rapamycin to reduce inhibition by NGF were similar in

magnitude and not additive, consistent with PI3K and mTOR as components of a

common inhibitory pathway. 5) Rapamycin selectively blocked PI3K-dependent

inhibition by NGF but had no effect on inhibition of

absorption were reduced by

rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTOR signaling (see below). 4) The effects

of PI3K inhibitors and rapamycin to reduce inhibition by NGF were similar in

magnitude and not additive, consistent with PI3K and mTOR as components of a

common inhibitory pathway. 5) Rapamycin selectively blocked PI3K-dependent

inhibition by NGF but had no effect on inhibition of

absorption by stimuli that act

through pathways not involving PI3K (angiotensin II and aldosterone). 6)

Inhibition of NHE1 by NGF was associated with an increased level of

phosphorylated mTOR in the basolateral membrane domain. 7) NGF-induced

stimulation of the mTOR target S6K was blocked by both PI3K inhibitors and

rapamycin. Taken together, these results support PI3K and mTOR as components

of a common signaling pathway that inhibits NHE1 and

absorption by stimuli that act

through pathways not involving PI3K (angiotensin II and aldosterone). 6)

Inhibition of NHE1 by NGF was associated with an increased level of

phosphorylated mTOR in the basolateral membrane domain. 7) NGF-induced

stimulation of the mTOR target S6K was blocked by both PI3K inhibitors and

rapamycin. Taken together, these results support PI3K and mTOR as components

of a common signaling pathway that inhibits NHE1 and

absorption. In mammalian cells,

the biochemical link between PI3K and mTOR involves Akt-induced

phosphorylation and inactivation of the protein tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2),

which negatively regulates mTOR through the small G protein Rheb

(25,

42,

46). Whether TSC2 and Rheb

play a role in mediating PI3K-mTOR-dependent regulation of NHE1 in the MTAL

remains to be determined. Inactivating mutations in the TSC2 gene lead to the

development of renal tumors that are sensitive to rapamycin, indicating an

important role for TSC suppression of mTOR signaling in renal cells

(25,

47,

48). The results of the

present study raise the possibility that mTOR-mediated regulation of NHE1

could play a role in mTOR-dependent renal cell proliferation and tumor

development.

absorption. In mammalian cells,

the biochemical link between PI3K and mTOR involves Akt-induced

phosphorylation and inactivation of the protein tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2),

which negatively regulates mTOR through the small G protein Rheb

(25,

42,

46). Whether TSC2 and Rheb

play a role in mediating PI3K-mTOR-dependent regulation of NHE1 in the MTAL

remains to be determined. Inactivating mutations in the TSC2 gene lead to the

development of renal tumors that are sensitive to rapamycin, indicating an

important role for TSC suppression of mTOR signaling in renal cells

(25,

47,

48). The results of the

present study raise the possibility that mTOR-mediated regulation of NHE1

could play a role in mTOR-dependent renal cell proliferation and tumor

development.

Rapamycin specifically inhibits mTOR by forming an inhibitory complex with

FKBP12, the intracellular rapamycin receptor. The rapamycin-FKBP12 complex

binds directly to mTOR, which destabilizes multiprotein mTOR signaling

complexes and inhibits the ability of mTOR to activate S6K and other

downstream signals (25,

46). The efficacy of rapamycin

in suppressing cell proliferation and the mammalian immune system has led to

its use in multiple clinical settings, including as an immunosuppressant in

kidney transplants, to prevent restinosis in cardiovascular stents, and as an

antitumor agent (25,

37,

42,

49,

50). Beneficial effects of

rapamycin to prevent progression of chronic kidney disease also have been

reported in experimental models

(51). Our study provides new

evidence that rapamycin at therapeutic concentrations influences the

regulation of NHE1 and its cell functions through inhibition of PI3K-mTOR

signaling. Rapamycin had no significant effect on NHE1 activity or

absorption under basal conditions

but impaired their regulation by NGF. In view of the defined roles of NHE1 in

cell growth, proliferation, and migration, it will be important in future

studies to determine whether the ability of rapamycin to modify NHE1

regulation via mTOR may contribute to the antiproliferative,

immunosuppressive, or antitumor properties of this drug. Our findings in the

MTAL also raise the possibility that rapamycin could impair the regulation of

renal tubule functions such as Na+ absorption and H+

secretion that depend on Na+/H+ exchange activity.

absorption under basal conditions

but impaired their regulation by NGF. In view of the defined roles of NHE1 in

cell growth, proliferation, and migration, it will be important in future

studies to determine whether the ability of rapamycin to modify NHE1

regulation via mTOR may contribute to the antiproliferative,

immunosuppressive, or antitumor properties of this drug. Our findings in the

MTAL also raise the possibility that rapamycin could impair the regulation of

renal tubule functions such as Na+ absorption and H+

secretion that depend on Na+/H+ exchange activity.

The two major downstream effectors of mTOR are S6K1, which enhances

translational efficiency, and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein

(4E-BP1), a translational repressor protein

(25,

46). We propose that S6K1

functions downstream of PI3K-mTOR to mediate NGF-induced inhibition of NHE1 in

the MTAL based on the following observations. First, NGF increased S6K

activity under conditions similar to those used in

transport experiments. Second, the

stimulation of S6K was blocked by wortmannin and rapamycin but not by the

MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126. Thus, the inhibitor sensitivity of S6K activation

correlates directly with that observed for PI3K-dependent inhibition of

transport experiments. Second, the

stimulation of S6K was blocked by wortmannin and rapamycin but not by the

MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126. Thus, the inhibitor sensitivity of S6K activation

correlates directly with that observed for PI3K-dependent inhibition of

absorption. Third, the

PI3K-mTOR-dependent transport regulation occurs within a time frame (<15

min) that correlates with increased S6K activity but is unlikely to be

mediated through mTOR-dependent up-regulation of transcriptional factors and

protein synthesis. Fourth, S6K is a member of the AGC family of

serine/threonine kinases that includes several well defined regulators of

epithelial transport proteins, including protein kinases A, C, and G, serum-

and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase, and p90 ribosomal S6 kinase

(52,

53). Our study is the first to

implicate a role for S6K in regulating Na+/H+ exchange

activity and the transport function of renal tubules. Because of the lack of

selective S6K inhibitors, we were unable to evaluate the functional

significance of S6K activation for Na+/H+ exchange

regulation in the perfused MTAL. Future studies using cell systems that enable

constitutive activation and/or knockdown of S6K will be required to establish

directly a role for S6K in NHE1 regulation. Additional mTOR-associated

proteins, such as protein phosphatase 2

(25,

54,

55), also could be involved in

mTOR regulation of NHE1 activity.

absorption. Third, the

PI3K-mTOR-dependent transport regulation occurs within a time frame (<15

min) that correlates with increased S6K activity but is unlikely to be

mediated through mTOR-dependent up-regulation of transcriptional factors and

protein synthesis. Fourth, S6K is a member of the AGC family of

serine/threonine kinases that includes several well defined regulators of

epithelial transport proteins, including protein kinases A, C, and G, serum-

and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase, and p90 ribosomal S6 kinase

(52,

53). Our study is the first to

implicate a role for S6K in regulating Na+/H+ exchange

activity and the transport function of renal tubules. Because of the lack of

selective S6K inhibitors, we were unable to evaluate the functional

significance of S6K activation for Na+/H+ exchange

regulation in the perfused MTAL. Future studies using cell systems that enable

constitutive activation and/or knockdown of S6K will be required to establish

directly a role for S6K in NHE1 regulation. Additional mTOR-associated

proteins, such as protein phosphatase 2

(25,

54,

55), also could be involved in

mTOR regulation of NHE1 activity.

Regulatory interactions between the PI3K-mTOR and ERK signaling pathways

have been described in other systems. For example, ERK1/2 can induce

p90RSK-catalyzed phosphorylation and inactivation of TSC2,

resulting in increased mTOR signaling and S6K activation independent of PI3K

(46,

56,

57). Conversely, rapamycin has

been shown to diminish growth factor-induced ERK activation in some cells, an

effect that may involve mTOR modulating ERK phosphorylation through PP2A

(55). Several findings suggest

that these interactions are minimal or absent in the MTAL, at least with

respect to NGF-induced inhibition of NHE1 and

absorption. First, the effect of

ERK inhibitors to diminish inhibition by NGF is quantitatively similar in the

absence or presence of a functional PI3K-mTOR pathway (Figs.

1 and

2) (Ref.

19), arguing against a

contribution of mTOR to ERK activation. Second, PI3K inhibitors reduce

NGF-induced inhibition by an amount virtually identical to that observed with

rapamycin (Figs. 1,

2,

3), arguing against an effect

of ERK to activate mTOR-dependent regulation independently of PI3K. Third,

activation of S6K by NGF was similar in the absence and presence of a MEK/ERK

inhibitor (Fig. 8). Thus, our

results provide no evidence for significant cross-talk between the PI3K-mTOR

and ERK pathways and suggest that these pathways function independently to

inhibit NHE1 and

absorption. First, the effect of

ERK inhibitors to diminish inhibition by NGF is quantitatively similar in the

absence or presence of a functional PI3K-mTOR pathway (Figs.

1 and

2) (Ref.

19), arguing against a

contribution of mTOR to ERK activation. Second, PI3K inhibitors reduce

NGF-induced inhibition by an amount virtually identical to that observed with

rapamycin (Figs. 1,

2,

3), arguing against an effect

of ERK to activate mTOR-dependent regulation independently of PI3K. Third,

activation of S6K by NGF was similar in the absence and presence of a MEK/ERK

inhibitor (Fig. 8). Thus, our

results provide no evidence for significant cross-talk between the PI3K-mTOR

and ERK pathways and suggest that these pathways function independently to

inhibit NHE1 and  absorption.

Previous studies also have identified an internal feedback loop within the

PI3K-mTOR-S6K pathway involving phosphorylation of mTOR by S6K. In this

mechanism, S6K is primarily activated downstream of PI3K via the

Akt-TSC1/2-Rheb-mTOR pathway. Activated S6K in turn directly phosphorylates

mTOR at Ser-2448 (28,

58). It is presently unclear

whether this feedback loop functions as a positive or negative regulator of

mTOR signaling (28,

58). In the MTAL we found that

NGF activates S6K via a PI3K- and mTOR-dependent pathway and that NGF

stimulation results in increased Ser-2448 phosphorylation of mTOR in the

basolateral membrane domain, consistent with feedback regulation of mTOR

through S6K. Further studies will be required to confirm this and to evaluate

the possibility that phosphorylation of mTOR by S6K may be involved in

basolateral mTOR targeting and/or in mTOR-dependent regulation of NHE1

activity.

absorption.

Previous studies also have identified an internal feedback loop within the

PI3K-mTOR-S6K pathway involving phosphorylation of mTOR by S6K. In this

mechanism, S6K is primarily activated downstream of PI3K via the

Akt-TSC1/2-Rheb-mTOR pathway. Activated S6K in turn directly phosphorylates

mTOR at Ser-2448 (28,

58). It is presently unclear

whether this feedback loop functions as a positive or negative regulator of

mTOR signaling (28,

58). In the MTAL we found that

NGF activates S6K via a PI3K- and mTOR-dependent pathway and that NGF

stimulation results in increased Ser-2448 phosphorylation of mTOR in the

basolateral membrane domain, consistent with feedback regulation of mTOR

through S6K. Further studies will be required to confirm this and to evaluate

the possibility that phosphorylation of mTOR by S6K may be involved in

basolateral mTOR targeting and/or in mTOR-dependent regulation of NHE1

activity.

PI3K has been shown to play a role in acute regulation of the epithelial

Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 by growth factors and other

stimuli (59,

60). In the MTAL,

hyposmolality increases NHE3 activity and

absorption through activation of

PI3K (13,

21). These effects are blocked

by rapamycin, indicating that mTOR functions downstream of PI3K to stimulate

NHE3 and

absorption through activation of

PI3K (13,

21). These effects are blocked

by rapamycin, indicating that mTOR functions downstream of PI3K to stimulate

NHE3 and  absorption in MTAL cells

(61). These findings can be

contrasted directly with the regulatory effects of NGF; activation of

PI3K-mTOR signaling by NGF results in inhibition of

absorption in MTAL cells

(61). These findings can be

contrasted directly with the regulatory effects of NGF; activation of

PI3K-mTOR signaling by NGF results in inhibition of

absorption through primary

inhibition of NHE1, with no direct coupling to NHE3

(Fig. 5) (Ref.

16). Thus, in the MTAL the

PI3K-mTOR pathway can be targeted specifically to inhibit basolateral NHE1 or

stimulate apical NHE3 depending on the physiological stimulus. The exact

mechanisms that target PI3K-mTOR signals to regulate different

Na+/H+ exchangers in different epithelial membrane

domains will be important to identify. The NGF-induced inhibition of NHE1 is

associated with an increase in phosphorylated mTOR in the basolateral

membrane. Thus, targeted activation of mTOR may be a component of PI3K-mTOR

signal specificity in MTAL cells.

absorption through primary

inhibition of NHE1, with no direct coupling to NHE3

(Fig. 5) (Ref.

16). Thus, in the MTAL the

PI3K-mTOR pathway can be targeted specifically to inhibit basolateral NHE1 or

stimulate apical NHE3 depending on the physiological stimulus. The exact

mechanisms that target PI3K-mTOR signals to regulate different

Na+/H+ exchangers in different epithelial membrane

domains will be important to identify. The NGF-induced inhibition of NHE1 is

associated with an increase in phosphorylated mTOR in the basolateral

membrane. Thus, targeted activation of mTOR may be a component of PI3K-mTOR

signal specificity in MTAL cells.

Neurotrophins and their receptors are highly expressed in the kidney, but

their roles in kidney function are not understood

(16). Our studies establish

directly that NGF can influence the transport function of renal tubules. The

change in  absorption induced by