Abstract

Reverse line blot hybridization assays (RLB) have been used for the rapid diagnosis and genotyping of many pathogens. The leishmaniases are caused by a large number of species, and rapid, accurate parasite characterization is important in deciding on appropriate therapy. Fourteen oligonucleotide probes, 2 genus specific and 12 species specific (2 specific for Leishmania major, 3 for L. tropica, 1 for L. infantum, 3 for L. donovani, and 3 for L. aethiopica), were prepared by using DNA sequences in the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) region of the rRNA genes. Probe specificity was evaluated by amplifying DNA from 21 reference strains using biotinylated ITS1 PCR primers and the RLB. The genus-specific probes, PP and PP3′, recognized all Leishmania species examined, while the species-specific probes were able to distinguish between all the Old World Leishmania species. Titrations using purified parasite DNA showed that the RLB is 10- to 100-fold more sensitive than ITS1 PCR and can detect <0.1 pg DNA. The RLB was compared to kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) and ITS1 PCR by using 67 samples from suspected cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) patients in Israel and the West Bank. The RLB accurately identified 58/59 confirmed positive samples as CL, a result similar to that found by kDNA PCR (59/59) and better than that by ITS1 PCR (50/59). The positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the RLB were 95.1% and 83.3%, respectively. L. major or L. tropica was identified by the RLB in 55 of the confirmed positive cases, a level of accuracy better than that of ITS1 PCR with restriction fragment length polymorphism (42/59). Thus, RLB can be used to diagnose and characterize Old World CL.

Leishmaniasis is a spectrum of diseases found in more than 88 countries worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 12 million people have leishmaniasis, and more than 350 million people living in regions of endemicity are at risk of infection (7, 29). The main forms of disease are cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis. Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) presents as a lesion or multiple skin lesions that self-heal within a few months to years. This disease generally responds well to treatment. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is a chronic disfiguring and debilitating disease with extensive destruction of the nasopharynx region that does not respond well to drug treatment. Finally, visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is in general fatal if not rapidly diagnosed and treated (7, 23).

There are at least 20 different species and subspecies of Leishmania. While many species are frequently associated with certain types of clinical pathology, other species can cause several forms of disease (7). This is further complicated by the fact that regions where different diseases and species are endemic may overlap, and leishmaniasis appears to be spreading into new regions previously free of disease (8). Since laboratories in regions where leishmaniasis is not endemic also see patients with different clinical syndromes and species, Leishmania species identification is important for disease prognosis and for the prescription of appropriate treatment for patients (4, 21).

Many different diagnostic techniques are being developed for the identification and characterization of Leishmania spp. Until recently, the “gold standard” was examination of stained microscope slides and/or parasite culture followed by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) analysis of the parasites (14, 21, 25). However, molecular techniques based on DNA amplification by PCR of various targets, either nuclear DNA or kinetoplast DNA (kDNA), are gradually replacing standard classical methods in many laboratories (2, 24). kDNA PCR using universal minicircle primers is considered the most sensitive diagnostic tool to date for detecting leishmaniasis. Diagnostic PCR using the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) region, located between the 18S and 5.8S rRNA genes, has been shown to be a sensitive and specific method for detecting Leishmania DNA in patients with CL or VL (2, 18, 26, 27). In addition, digestion of the PCR product (amplicon) with restriction enzymes allows identification of almost all pathogenic Leishmania species, thus enabling direct, rapid characterization of the infecting parasite (26). We have now taken advantage of the DNA sequence polymorphism in the ITS1 region to develop a reverse line blot hybridization assay (RLB) that allows the identification of Old World Leishmania species simultaneously in a large number of samples. In RLBs, biotinylated PCR products hybridize specifically to oligonucleotide probes coupled to a membrane support. Using appropriate hybridization conditions, it is possible to differentiate between amplicons whose DNA sequences differ by only one nucleotide, allowing rapid identification of species and organisms. Hybridization between the biotinylated amplicon and the probe on the membrane is detected by either colorimetric or chemiluminescent procedures (15).

Oligonucleotide probes specific for Leishmania donovani, L. infantum, L. major, L. tropica, and L. aethiopica were designed and covalently coupled to a membrane. Probe specificity was examined using Leishmania reference strains. Finally, the specificity and sensitivity of the ITS1 RLB were compared with those of both kDNA PCR and ITS1 PCR by using samples from putative CL patients from Israel and the West Bank. Our results show that the ITS1 RLB will be useful for the specific and sensitive diagnosis of leishmaniasis in patient samples and for epidemiological studies where a large number of humans, animals, or sand flies need to be analyzed.

(This publication counts toward the partial fulfillment by A. Nasereddin of Ph.D. requirements at the Charité University Medicine, Berlin, Germany.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling.

Samples were taken from 67 patients referred to the Dermatology Department of the Hadassah Hospital, Jerusalem, Israel, with suspected CL. All of the patients were infected in Israel or the West Bank region. Ages ranged from 2 to 75 years. Males comprised 60% and females 40% of the population.

Procedures for sampling patient lesions, culturing parasites, staining tissue smears with Wright's Giemsa stain, and preparing filter papers have been described previously (2). Filter papers were stored with silica gel at 4°C until the DNA was extracted and samples were analyzed by PCR blindly. The Helsinki Committee for Human Research of the Hadassah Hospital, Ein Kerem, Jerusalem, approved this study.

DNA extraction and PCR.

Each specimen was cut from the filter paper with a disposable sterile scalpel and incubated in 250 μl cell lysis buffer as previously described (2). DNA was extracted from the lysates with phenol-chloroform, and the pellets were air dried. After the DNA was dissolved in 50 μl TE buffer (10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), it was kept at 4°C until analysis by PCR. Clean filter paper was used as a negative control for DNA extraction. kDNA PCR was carried out as previously described (2) using primers 13A (5′-GTG GGG GAG GGG CGT TCT-3′) and 13B (5′-ATT TTC CAC CAA CCC CCA GTT-3′). ITS1 PCR was carried out using the 5′-biotinylated primers LITSR (5′-CTG GAT CAT TTT CCG ATG-3′) and L5.8S (5′-TGA TAC CAC TTA TCG CAC TT-3′) essentially as described by Schonian et al. (26), except that 300 nM primers, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 2.5% dimethyl sulfoxide were used. Leishmanial DNA (20 ng) isolated from reference strains (see below) was used as a positive control. Reaction buffers without leishmanial DNA were also included as negative controls in each PCR analysis. All PCRs were carried out in a 50-μl volume, using the optimal annealing temperatures, concentrations of primers, deoxynucleoside triphosphates, Mg ions, Taq polymerase, and additives as necessary. Inhibition was monitored when all PCRs were negative by adding a control plasmid as described previously (2) to patient DNA extracted from the filter papers and carrying out separate PCRs.

ITS1 or kDNA PCR amplicons were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gels (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, ME) by electrophoresis at 100 V in 1× TAE buffer (0.04 M Tris acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) and visualized by UV light after staining with ethidium bromide (0.3 μg/ml). A PCR result was considered positive when a ∼ 300- to 350-bp (ITS1) or 120-bp (kDNA) band was observed. The product size of the ITS1 PCR differs with the Leishmania species (26).

Reference parasite DNA was prepared as previously described (26) from promastigotes of L. aethiopica (MHOM/ET/1972/LRC-L149 and MHOM/ET/1985/LRC-L495), L. donovani (MHOM/IN/1980/DD8, MHOM/ET/1967/HU3, MHOM/SD/1962/1S-Cl D2, MHOM/IN/??/WR352, MHOM/IL/1998/LRC-L740, and MHOM/IL/1979/LRC-L264), L. guyanensis (MHOM/BR/1975/LRC-L326), L. infantum (MHOM/TN/1980/IPT1, MHOM/PS/1999/LRC-L773, MCAN/IL/1997/LRC-L720, MCAN/IL/1999/LRC-L760, and MCAN/IL/1997/LRC-L716), L. major (MHOM/SU/1973/5ASKH, MHOM/PS/1998/LRC-L749, MHOM/PS/1998/LRC-L750, MHOM/IL/1986/LRC-L509, and IPAP/IL/1998/LRC-L746), and L. tropica (MHOM/IL/1997/LRC-L725 and MHOM/IL/1959/LRC-L22). Strains were obtained from the WHO Reference Centre, Jerusalem, Israel.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis.

ITS1 PCR products (8 to 20 μl) were digested with BsuRI (Fermentas, MBI), an HaeIII prototype, according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the restriction fragments were analyzed by gel electrophoresis at 120 V in 1× TAE buffer in 2.5% agarose gels. The fragments were visualized by UV light, and the sizes of the restriction products were determined.

RLB oligonucleotide probes.

DNA sequences for the Leishmania ITS1 region were compared by multialignment (ClustalW2; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html). All ITS1 sequences used for analysis except four were obtained from the NCBI nucleotide database. Genomic DNAs from these Leishmania strains (LRC-L149, LRC-L495, LRC-L784, and LRC-L758; accession no. EU683619, EU683620, EU683618, and EU683617, respectively) and Leptomonas seymouri ATCC 30220 (accession no. EU623433) were amplified by ITS1 PCR and sequenced at the Center for Genomic Technologies, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The melting temperature (Tm) of each probe was calculated using the BioMath calculator at the Promega website, and the specificity of each probe was examined by searching a nonredundant nucleotide database (Megablast, NCBI) for highly similar sequences.

ITS1 RLB.

The 5′-amine-labeled oligonucleotide probes used in this study are shown in Table 1. The probes were covalently coupled to negatively charged membranes (Biodyne C; Pall Life Sciences, MI) following activation of the membrane for 15 to 30 min at room temperature with 10% (wt/vol) 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide essentially as described previously (15). The activated membrane was rinsed with distilled water and placed in a miniblotter (MN45; Immunetics, Cambridge, MA). Each leishmanial species probe (7 pmol/μl, 0.5 M NaHCO3 [pH 8.4]) was applied to a separate slot for 1 min; the solutions were removed; and the membrane was then inactivated by incubation in 0.1 M NaOH for 5 min. Membranes were washed several times with excess distilled water, dried 15 to 20 min, and stored in sealed plastic bags at 4°C until use.

TABLE 1.

Probes used in RLB analysis of ITS1 PCR amplicons

| Name | DNA sequence | Length (bp) | Tm (°C) | Leishmania specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | TTT CCG ATG ATT ACA CC | 17 | 42 | Genus |

| PP3′ | GAT AAC GGC TCA CAT AAC GTG T | 22 | 53 | Genus |

| LmP28 | GAT TAC ACC CCA AAA AAC AT | 20 | 46 | L. major |

| RLmE1 | TAT CCA CGC GCA CGC A | 16 | 49 | L. major |

| RLtP | TCC ACA CAC ACG CAC CC | 17 | 52 | L. tropica |

| LtE1 | TCC CAC ACA TAC ACA GC | 17 | 47 | L. tropica |

| LtP28a | AAA ACA TAT ACA AAA CTC GGG | 21 | 47 | L. tropica |

| Ld | GAT GAT TAC ACC AAA AAA AAC | 21 | 45 | L. donovani |

| Ldn | CGA TGA TTA CAC CAA AAA AAC | 21 | 47 | L. donovani |

| Ld2 | TTA CAC CAA AAA AAA CAT ATA C | 22 | 44 | L. donovani |

| Li | TTA CAC CCA AAA AAC ATA TAC | 21 | 45 | L. infantum |

| Laet1 | GCG CGC CTA TAC ACA CAA | 18 | 50 | L. aethiopica |

| Laet1a | CAC CGC GCG CCT ATA CA | 17 | 52 | L. aethiopica |

| Laet2 | TTT CCG TCT TTT GTT GGC G | 19 | 49 | L. aethiopica |

Prior to use, the membranes were rotated 90° and cut into 0.5-cm strips such that each strip contains parallel lanes from each probe. The strips were washed and incubated separately at 46°C for 30 min in hybridization buffer (30 mM sodium citrate-0.3 M NaCl [pH 7.0] [2× SSC] containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]). The biotinylated PCR products (20 μl) were boiled for 10 min and rapidly placed on ice (2 min). Hybridization was carried out by adding one PCR product per strip in 5 ml 2× SSC-0.1% SDS buffer for 1 h at 46°C. The membrane strips were then washed with 0.75× SSC-0.1% SDS for 30 min at 46°C and incubated with streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:3,500 dilution in 2× SSC-0.1% SDS [Roche]) for 20 min at room temperature. The strips were then washed three times, for 2 min each time, at room temperature with 2× SSC-0.1% SDS and then three times with 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 5.0). The positive reactions were detected by development for 10 min with a solution containing 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl benzidine (0.1 mg/ml; Sigma Life Science) in sodium citrate buffer containing 30% H2O2 (1/10,000 dilution).

Statistics.

Specimens were considered confirmed positive (C-pos) when cultures or stained tissue smears were positive for parasites or at least two PCR assays were positive for leishmanial DNA. When all the assays were negative or only one PCR was positive for parasite DNA, specimens were considered confirmed negative (C-neg). These values were used as the “consensus standards” against which each individual diagnostic assay was compared. Data were analyzed using the on-line statistics calculator at the GraphPad Software website. Cohen's kappa coefficient (κ) is a measure of the agreement between two tests beyond that expected by chance, where 0 is chance agreement and 1 is perfect agreement (19).

RESULTS

Selection of RLB probes.

Forty leishmanial DNA sequences for the ITS1 region, located between the 16S and 5.8S rRNA genes, were compared by multialignment. Sequences from L. donovani (21), L. infantum (7), L. major (4), L. tropica (5), and L. aethiopica (3) were used. Strains from different foci were selected in order to compensate for potential variation in the ITS1 sequence among Leishmania species that are distributed over wide geographical regions. For example, the L. tropica sequences were from strains originating in Namibia, Kenya, Tunisia, the Palestinian Authority, and Israel, while the L. donovani sequences came from Sudanese, Kenyan, Ethiopian, and Indian strains. Calculated Tms for the designed probes ranged from 42 to 53°C, and length ranged from 17 to 22 bp. Probes were designed so that the unique nucleotides were in the middle or on the 3′ end of the sequence. An amino group was added to the 5′ end for coupling to the activated membrane. Except in the case of L. infantum, several specific probes were made for each species (Table 1). In addition, two genus-specific probes, PP and PP3′, were designed to recognize all Leishmania species, both Old and New World species. Searches of the NCBI nucleotide database for Leishmania ITS sequences found 188 hits; however, several of these included only the ITS2 and not the ITS1 region. A more restricted search for only the ITS1 region found 148 sequences. A Megablast search of PP3′ against the NCBI nucleotide database identified 176 Leishmania ITS1 sequences with 100% identity and no gaps over the full probe length (perfect match), including both New and Old World species such as L. donovani, L. infantum, L. major, L. tropica, L. aethiopica, L. amazonensis, L. braziliensis, L. guyanensis, L. panamensis, L. naiffi, L. lainsoni, and L. chagasi. This search using the PP3′ probe sequence found additional Leishmania ITS1 sequences, because some database entries do not include ITS1 in the title. Similar results were obtained for the PP probe sequence, except that fewer ITS1 sequences (117 perfect matches) were identified. Therefore, both PP and PP3′ are potentially useful as genus-specific probes for identifying Leishmania species. Importantly, sequences from Trypanosoma cruzi or African trypanosomes were not included in the Megablast results using either PP or PP3′. It should also be noted that the ITS1 PCR does not amplify DNA from these human parasites (reference 26 and unpublished data).

Megablast searches were also carried out with the Old World Leishmania-specific probes listed in Table 1 for sequences showing 100% identity. Probes LmP28 and RLmE1 were highly specific for L. major, identifying 17/18 and 18/18, respectively, of the sequences recognized by PP3′. Likewise, probes RLtP, LtE1, and LtP28a together identified all seven L. tropica ITS1 sequences in the data bank. The latter two probes, LtE1 and LtP28a, also gave high sequence identity with a few L. infantum strains, 1/32 and 2/32, respectively. The three L. aethiopica probes, Laet1, Laet1a, and Laet2, showed perfect matches only with this species.

Three L. donovani probes and one L. infantum probe were also designed based on multialignment using 28 available sequences for these species. Megablast analysis using Ld or Ld2 sequences showed 100% identity with 24/59 sequences listed as L. donovani in the NCBI nucleotide database. Probe Ldn retrieved six additional strains missed by the other two probes; thus, together the three probes identified 30/59 putative perfect matches for L. donovani strains. Ld also showed high identity (100% over 20/21 bp, with no gaps) with two additional strains missed by Ldn and Ld2.

Interestingly, 21/59 ITS1 sequences listed in the nucleotide database as “L. donovani” and isolated from VL patients in India were not retrieved by Blast analysis using any of the L. donovani probes. These strains showed relatively low sequence identity (45% over 396 bp) with the ITS1 sequence (accession no. AJ000292) of the WHO reference strain of L. donovani (MHOM/IN/1980/DD8). Further analysis showed that the DNA sequences for these 21 strains are essentially the same (99% identical over 396 bp) as that of Leptomonas seymouri ATCC 30220 (accession no. EU623433), indicating that these parasites are not Leishmania spp. As such, it is not surprising that they show low-level sequence similarity with the L. donovani probes. Finally, 6/59 “L. donovani” strains, five from Sudan and one from China, showed only partial identity with the L. donovani probes. These strains all have ITS sequence type C (17) and were perfect matches with the L. infantum probe Li.

Good results were also found using the L. infantum probe, Li, which gave perfect matches with 27/34 (79%) of the L. infantum (synonym, L. chagasi) sequences deposited in the database. All the European and South American strains (n = 27) representing “true zoonotic L. infantum” (17) were retrieved. Interestingly, the remaining seven “L. infantum” strains missed by the probe were from Sudan and were retrieved by BLAST analysis with L. donovani probe sequences. In the past, characterization of visceralizing species in East Africa was based exclusively on MLEE analysis, which separated these strains into three species: L. donovani, L. infantum, and L. archibaldi. Studies showed that this classification was based on a single-nucleotide polymorphism that affected the migration of one enzyme, glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (13). Recently, the status of these species was newly evaluated in a series of publications (13, 16, 20). Based on microsatellite markers and the phylogenetic analysis of other gene sequences, it was concluded that the name L. archibaldi is invalid and that isoenzymes cannot be used to distinguish between L. donovani and L. infantum in Sudan. Therefore, the L. donovani and L. infantum probes correctly identified 97.2% of the strains causing VL.

ITS1 RLB standardization.

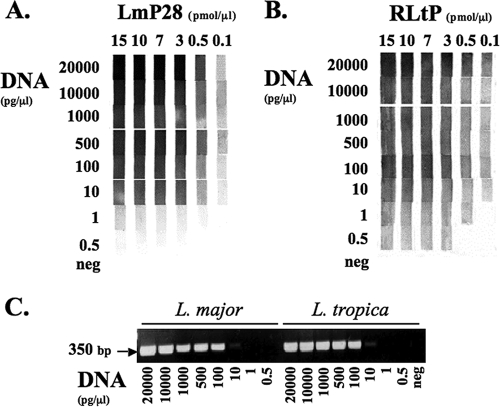

The optimal probe concentration for coupling to the Biodyne C membrane was determined by cross titration using decreasing concentrations of leishmanial DNA in the ITS1 PCR (Fig. 1 and data not shown), followed by the RLB. A typical result is shown for two probes, LmP28 and RLtP (Fig. 1A and B, respectively). When 3 pmol/μl probe was coupled to the membrane, good reactions were observed down to 10 pg/μl L. major or L. tropica DNA. Weak but distinct positive reactions were still present even when 1 or 0.5 pg/μl L. major or L. tropica DNA, respectively, was used in the PCR. No increase in the sensitivity or color reaction was observed if higher probe concentrations were used for coupling. However, when lower concentrations were used (0.5 or 0.1 pmol/μl probe), losses in both ITS1 RLB sensitivity and color intensity were observed. Similar results were obtained with the other probes, though the intensity of the colorimetric product differed for each probe. Therefore, in order to ensure optimal sensitivity, 3 pmol/μl probe was used in all subsequent RLB studies.

FIG. 1.

Standardization of the Leishmania RLB probe binding concentration and comparison of the sensitivities of the ITS1 RLB and PCR. Decreasing concentrations of leishmanial DNA were amplified by ITS1 PCR using biotinylated primers (LITSR and L5.8S). PCR products were analyzed either by the RLB or by gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide. Cross titration shows the effect of probe coupling and DNA concentrations on the sensitivity of the RLB. (A) L. major probe (LmP28) with L. major (LRC-L746) DNA; (B) L. tropica probe (RLtP) with L. tropica (LRC-L22) DNA; (C) ITS1 PCR analysis of L. major and L. tropica DNAs by agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5%) and staining with ethidium bromide. The negative control (neg) contained no DNA in the PCR.

The sensitivities of the ITS1 RLB and PCR were compared (Fig. 1 and data not shown) by carrying out parallel PCRs on decreasing dilutions of Leishmania DNA. PCR products could be easily detected by gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining down to 100 pg/μl L. major or L. tropica DNA, and faint bands were still visible at 10 pg/μl DNA. However, bands were not observed when PCR was carried out with lower DNA concentrations (Fig. 1C). Detection by the RLB was at least 10-fold higher, since for both species (L. major [LmP28] and L. tropica [RLtP]), bands were clearly detected down to at least 1 pg/μl DNA (Fig. 1A and B).

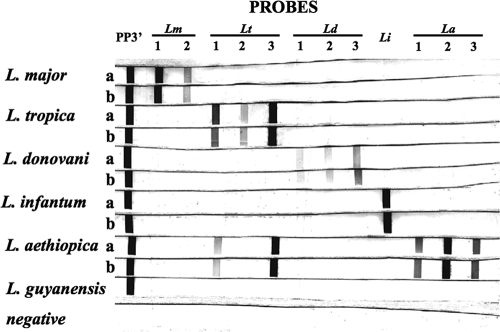

Differences in the sensitivity of the ITS1 RLB were seen depending on the probe used (Fig. 2). The abilities of the L. tropica probes, RLtP, LtE1, and LtP28a, to detect products from PCRs carried out using decreasing amounts of L. tropica DNA (500 pg/μl to 0.03 pg/μl) were compared. The sensitivities of all three RLB probes were at least as good as that of the ITS1 PCR (10 pg/μl). LtE1 was the least sensitive probe, giving faint bands at 5 and 10 pg/μl DNA. RLtP showed intermediate sensitivity, detecting 0.5 pg/μl of L. tropica DNA, while probe LtP28a had the highest sensitivity, easily detecting the PCR product at 0.06 pg/μl DNA. The RLB with probe LtP28a was at least 166-fold more sensitive than detection by gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide.

FIG. 2.

Effects of different L. tropica probes on the ability of the RLB to detect DNA. ITS1 PCR was carried out with biotinylated primers (LITSR and L5.8S) using decreasing concentrations of L. tropica DNA. The PCR products were incubated with membrane strips containing each of the L. tropica probes RLtP, LtE1, and LtP28a (3 pmol/μl). The RLB was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. The negative control (neg) contained no DNA in the PCR.

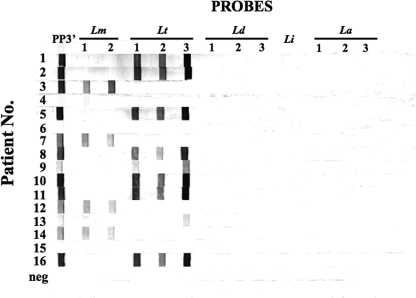

The specificities of the probes (Fig. 3 and data not shown) were examined by carrying out the ITS1 RLB with DNAs purified from two strains each of different Old World leishmaniae: L. major, L. tropica, L. infantum, L. donovani, and L. aethiopica. L. guyanensis, a New World Leishmania species, was also included. The genus-specific probes PP and PP3′ recognized all of the different Leishmania spp. examined (Fig. 3 and data not shown); however, PP3′ gave a much stronger signal than PP (data not shown). Differences in the intensity of the reaction with the horseradish peroxidase substrate, as already described, were seen between probes, with some giving much stronger bands under identical hybridization conditions. All of the species probes, except for two L. tropica probes, were highly specific, hybridizing only with PCR products amplified from the same species. LmP28 and RLmE1 reacted only with DNA amplified from L. major (Fig. 3, Lm 1 and 2, respectively). Likewise, L. donovani probes (Ld, Ldn, and Ld2 [Fig. 3, Ld 1 to Ld 3) recognized only PCR amplicons from L. donovani, and Li recognized only the L. infantum ITS1 PCR products. The L. aethiopica probes (Laet1, Laet1a, and Laet2 [Fig. 3, La 1 to La 3) hybridized exclusively with amplicons from this species. The L. tropica probes (Fig. 3, Lt 1 to Lt 3) hybridized to PCR products of L. tropica but not to those of L. major, L. donovani, or L. infantum; however, two probes, RLtP and LtP28a (Fig. 3, Lt 1 and Lt 3, respectively), showed clear reactions with DNA amplified from L. aethiopica. Comparison of the ITS1 DNA sequences of L. tropica and L. aethiopica showed that the RLtP probe sequence is present in both species; however the LtP28a sequence was found only in L. tropica. While it is not surprising that RLtP recognizes DNA amplified from L. aethiopica, the reason for the unexpected hybridization of LtP28a with this PCR product is unclear. Increasing the hybridization temperature to 48°C did not eliminate the nonspecific hybridization (data not shown). Even taking into account the cross-reaction of LtP28a and RLtP with L. aethiopica DNA, these parasites were easily distinguished from L. tropica, since the L. aethiopica probes reacted only with the latter species. Together these results demonstrate that a set of RLB probes is available to identify and distinguish between the Old World Leishmania species.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of RLB specificity for Old World Leishmania spp. RLB membranes were prepared by coupling each of the species-specific probes and the genus-specific probe PP3′. Species-specific probes are as follows: for L. major, Lm 1 (LmP28) and Lm 2 (RLmE1); for L. tropica, Lt 1 (RLtP), Lt 2 (LtE1), and Lt 3 (LtP28a); for L. donovani, Ld 1 (Ld), Ld 2 (Ldn), and Ld 3 (Ld2); for L. infantum, Li (Li); and for L. aethiopica, La 1 (Laet1), La 2 (Laet1a), and La 3 (Laet2). ITS1 PCRs using biotinylated primers (LITSR and L5.8S) were carried out using DNA (500 pmol/reaction) from L. major (rows a and b, LRC-L749 and -L746, respectively), L. tropica (rows a and b, LRC-L22 and -L725, respectively), L. donovani (rows a and b, LRC-L264 and -L740, respectively), L. infantum (rows a and b, LRC-L720 and -L716, respectively), L. aethiopica (rows a and b, LRC-L149 and -L495, respectively), or L. guyanensis. The RLB was carried out by incubating each PCR product with a membrane strip containing all the probes. A negative control containing no DNA in the PCR was also used in the RLB.

Diagnosis of Old World CL by ITS1 RLB and PCR.

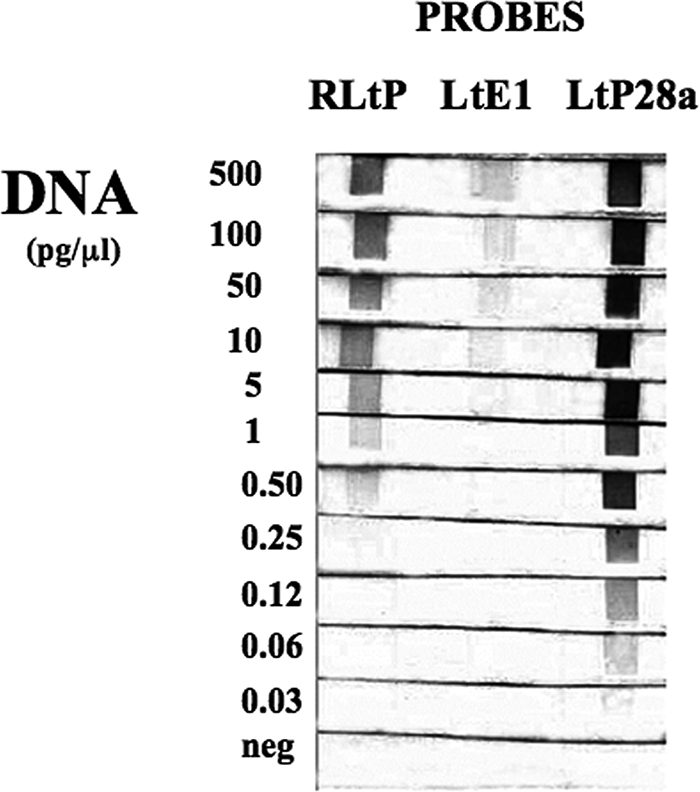

Samples from 67 putative CL patients in Israel and the West Bank were analyzed by kDNA PCR, ITS1 PCR, ITS1 RLB, parasite culturing, and microscopic examination of stained smears. According to the consensus criteria, 59 (88%) and 8 (12%) of the samples received for diagnosis were C-pos and C-neg, respectively. Typical results for the RLB are shown in Fig. 4. The RLB was considered positive, even in the absence of a reaction with one of the Leishmania species probes, as long as the genus-specific probe showed a clear reaction. The specificity and sensitivity for each molecular assay are given in Table 2.

FIG. 4.

Diagnosis of Old World CL by the ITS1 RLB. DNA was extracted from filter papers containing lesion material previously aspirated from patients in Israel or the West Bank with putative CL. ITS1 PCR was carried out using biotinylated primers (LITSR and L5.8S), and the denatured PCR product (rows 1 to 16) was incubated with membrane strips containing oligonucleotide probes specific to the covalently linked species (n = 12) and the genus Leishmania (n = 1) (see Fig. 3 for individual probe specificities). After 1 h at 46°C, the strips were washed several times at the same temperature and then incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (1:3,500 dilution) at room temperature for 20 min. After several washes, the hybridized DNA bound to the membrane was detected by adding the substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl benzidine (2 mg/ml) in sodium citrate buffer containing 30% H2O2 (1/10,000 dilution). A negative control (neg) containing no DNA in the PCR was also used in the RLB.

TABLE 2.

Detection of Old World CL by PCR and RLB

| Assaya | No. of samples

|

% of samples

|

Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos | Neg | C-pos | C-neg | |||||

| kDNA PCR | 60 | 7 | 89.6 | 10.4 | 100 | 87.5 | 98.3 | 100 |

| ITS1 PCR | 50 | 17 | 74.6 | 25.4 | 84.7 | 100 | 100 | 47.0 |

| ITS1 RLB | 61 | 6 | 91.0 | 9.0 | 98.3 | 62.5 | 95.1 | 83.3 |

| Total | 59 | 8 | 88.0 | 12.0 | ||||

“Total” represents the results for the C-pos and C-neg samples. C-pos samples were positive by at least two molecular diagnostic assays (PCR or RLB) or by parasite culture and/or microscopic examination of tissue smears. C-neg samples were positive by only one molecular diagnostic assay and no other technique.

By the kDNA PCR, 60 of the 67 patient samples were positive (89.6%). This included all 49 samples that were positive either by culture and/or by microscopy. This PCR had the best sensitivity (100%) and specificity (87.5%) of the three molecular tests, correctly diagnosing all the C-pos samples and misdiagnosing only (false positive) one of the eight C-neg samples. The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) for this assay were 98.3 and 100%, respectively, and Cohen's kappa coefficient (κ = 0.925 ± 0.146) indicated very good agreement between kDNA PCR and diagnosis based on the consensus criteria, C-pos and C-neg.

The ITS1 PCR correctly identified 50/67 (74.6%) of the samples (50 C-pos and 8 C-neg). Its sensitivity, as expected from previous studies, was somewhat lower (84.7%) than that of the kDNA PCR, but its specificity was excellent (100%). No false positives were seen, but nine positive patient samples detected by the kDNA PCR were missed (false negatives). These included six samples that were positive either by culture and/or by microscopic examination. The PPV and NPV for the ITS1 PCR were 100% and 47%, respectively. The agreement between the confirmed results and the ITS1 PCR was only moderate (κ = 0.576 ± 0.261).

By the ITS1 RLB, 61 (91%) of the 67 samples were positive. Typical results for the RLB using patient samples are shown in Fig. 4, where positive results are seen with samples 1 to 3, 5, 7 to 14, and 16, and negative results are seen with samples 4, 6, and 15. The sensitivity (98.3%) of the RLB approached that observed with kDNA PCR, and only one false-negative (1/59 C-pos samples) was encountered. This sample was positive by both microscopic examination and kDNA PCR. Eight C-pos samples missed by ITS1 PCR were positive by the RLB. The specificity (62.5%) of the RLB was somewhat lower than those of the PCR assays. This was due to three false-positive results, for two of which the sample reacted weakly only with the genus-specific probe PP3′, suggesting that a sample should be considered positive only when two probes, at least one of which is a species-specific probe, are positive. The PPV and NPV for the RLB were 95.1% and 83.3%, respectively. Agreement with the confirmed results (κ = 0.686 ± 0.302) was considered good.

One main advantage of both the ITS1 RLB and ITS1 PCR over kDNA PCR is their ability to identify Leishmania species causing CL. ITS1 PCR, followed by restriction enzyme analysis (RFLP), was able to identify the parasite species (L. major [n = 21] or L. tropica [n = 21]) in 42/59 C-pos samples (71.2%). The RLB (Fig. 4 and data not shown) identified the species causing disease in 53/59 C-pos samples (89.8%), including 11 C-pos samples classified as undetermined by RFLP. In 52/53 samples, at least two species-specific probes, either for L. major (n = 27) or for L. tropica (n = 26), were positive in addition to the genus-specific probe PP3′. There was 100% agreement between RFLP and the RLB where the Leishmania species were determined by both assays. For five patients for whom the species could not be determined by the RLB, a reaction was observed only with the genus probe. These undetermined positives were confirmed by kDNA PCR and/or ITS1 PCR, and one sample was also smear positive. No cases of CL caused by L. infantum, L. donovani, or L. aethiopica were seen in these patient samples.

DISCUSSION

Molecular techniques are gradually supplanting classical techniques such as promastigote culture and microscopic smear examination in the diagnosis of leishmaniasis (24). While serological assays have proved useful for diagnosing VL (5), PCR is now the diagnostic method of choice for CL or mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, and kDNA PCR is the gold standard against which all new techniques should be compared (2, 24). However, the inability or at best limited ability of kDNA PCR to characterize Leishmania spp. at the species level is a major drawback (1, 9). Several PCRs against polymorphic regions, such as the spliced leader mini-exon (10 parasites/reaction), gp63, heat shock protein 70 (30 parasites/reaction), and ITS1 (0.2 parasite/reaction) PCRs, have been developed (12, 22, 26, 28). When combined with RFLP, they can identify the infecting Leishmania species, but the sensitivities of these assays do not compare to that of kDNA PCR (2, 18).

The Leishmania RLB takes advantage of polymorphism in the ITS1 region to identify Old World Leishmania species (3, 11, 17, 26). Detection of a positive reaction via hybridization of the biotinylated amplicon to a species-specific probe and subsequent signal amplification by streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase increases the limit of detection 10- to >100-fold over that of RFLP. The sensitivity of the RLB (98.3%) was comparable to that obtained using the kDNA PCR (100%) and significantly better than that of the ITS1 PCR, detecting several positive patients missed by the latter assay. In addition, the RLB successfully characterized the Leishmania species in ∼90% of the positive cases, also confirming reactions observed with the genus probe. All of the CL patients examined in this study were infected with either L. tropica or L. major. This finding is not surprising, since CL caused by L. infantum, L. donovani, or L. aethiopica in Israel and the Palestinian Authority is either extremely rare or not found. Studies in foci where the latter species are endemic would be useful for further validation of the RLB assay.

Colorimetric or chemiluminescent substrates can be used interchangeably, allowing either direct detection of the reaction product or further enhancement using exposure to X-ray film, respectively. The latter technique also allows stripping and reuse of the same RLB membrane several times, which can reduce costs. In addition, RLB membranes can be stored sealed at 4°C for at least 4 months with no loss of sensitivity (reference 15 and data not shown).

Differences in the intensity of the colorimetric product were observed between the different probes available for the same species. Similar results have been reported for RLBs with other organisms (30), and variability does not seem to be correlated with either the probe length or the Tm. Instead, it may be associated with the internal folding and secondary structure of the single-strand DNA product, interfering with probe annealing to the DNA during the hybridization step of the RLB.

The Leishmania RLB is simple to carry out and, except for a PCR thermocycler, does not require any additional equipment for gel electrophoresis, UV detection, and image capturing or for disposal of ethidium bromide, a carcinogen. While PCR with RFLP requires about 3 h for analysis of the reaction product and determination of the parasite species of positive samples, RLB takes <2 h. In addition, it should be possible to further simplify RLB by using PCR-oligochromatography and developing dipsticks, similar to those used to detect animal and human trypanosomes or toxoplasmosis, where detection can be obtained within 5 min of completion of the PCR. This would further simplify the analysis of CL samples (6, 10).

The Leishmania RLB will be useful for epidemiological studies where large number of samples need to be screened. It has been used successfully to screen potential reservoir hosts and vectors in Israel (Alon Warburg and Laor Orshan, personal communication).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the U.S. Middle East Regional Cooperation (MERC) Project, NIH-NIAID contract TA-MOU-030M23-015.

We thank Lee Schnur for maintaining the WHO Jerusalem Reference Center for Leishmaniases (WHO-LRC) and providing the reference strains used in this study. We also thank Flory Jonas, Department of Dermatology, for help in obtaining the patient samples.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders, G., C. L. Eisenberger, F. Jonas, and C. L. Greenblatt. 2002. Distinguishing Leishmania tropica and Leishmania major in the Middle East using the polymerase chain reaction with kinetoplast DNA-specific primers. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96(Suppl. 1)S87-S92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bensoussan, E., A. Nasereddin, F. Jonas, L. F. Schnur, and C. L. Jaffe. 2006. Comparison of PCR assays for diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 441435-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berzunza-Cruz, M., N. Cabrera, M. Crippa-Rossi, T. Sosa Cabrera, R. Pérez-Montfort, and I. Becker. 2002. Polymorphism analysis of the internal transcribed spacer and small subunit of ribosomal RNA genes of Leishmania mexicana. Parasitol. Res. 88918-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum, J., P. Desjeux, E. Schwartz, B. Beck, and C. Hatz. 2004. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis among travellers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53158-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chappuis, F., S. Rijal, A. Soto, J. Menten, and M. Boelaert. 2006. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of the direct agglutination test and rK39 dipstick for visceral leishmaniasis. BMJ 333723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claes, F., S. Deborggraeve, D. Verloo, P. Mertens, J. R. Crowther, T. Leclipteux, and P. Buscher. 2007. Validation of a PCR-oligochromatography test for detection of Trypanozoon parasites in a multicenter collaborative trial. J. Clin. Microbiol. 453785-3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desjeux, P. 2004. Leishmaniasis: current situation and new perspectives. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desjeux, P. 2001. The increase in risk factors for leishmaniasis worldwide. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95239-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disch, J., M. J. Pedras, M. Orsini, C. Pirmez, M. C. de Oliveira, M. Castro, and A. Rabello. 2005. Leishmania (Viannia) subgenus kDNA amplification for the diagnosis of mucosal leishmaniasis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 51185-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edvinsson, B., S. Jalal, C. E. Nord, B. S. Pedersen, and B. Evengard. 2004. DNA extraction and PCR assays for detection of Toxoplasma gondii. APMIS 112342-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elfari, M., L. F. Schnur, M. V. Strelkova, C. L. Eisenberger, R. L. Jacobson, C. L. Greenblatt, W. Presber, and G. Schönian. 2005. Genetic and biological diversity among populations of Leishmania major from Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Microbes Infect. 793-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia, L., A. Kindt, H. Bermudez, A. Llanos-Cuentas, S. De Doncker, J. Arevalo, K. W. Quispe Tintaya, and J. C. Dujardin. 2004. Culture-independent species typing of neotropical Leishmania for clinical validation of a PCR-based assay targeting heat shock protein 70 genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 422294-2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamjoom, M. B., R. W. Ashford, P. A. Bates, M. L. Chance, S. J. Kemp, P. C. Watts, and H. A. Noyes. 2004. Leishmania donovani is the only cause of visceral leishmaniasis in East Africa; previous descriptions of L. infantum and “L. archibaldi” from this region are a consequence of convergent evolution in the isoenzyme data. Parasitology 129399-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalter, D. C. 1994. Laboratory tests for the diagnosis and evaluation of leishmaniasis. Dermatol. Clin. 1237-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong, F., and G. L. Gilbert. 2006. Multiplex PCR-based reverse line blot hybridization assay (mPCR/RLB)—a practical epidemiological and diagnostic tool. Nat. Protoc. 12668-2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhls, K., L. Keilonat, S. Ochsenreither, M. Schaar, C. Schweynoch, W. Presber, and G. Schonian. 2007. Multilocus microsatellite typing (MLMT) reveals genetically isolated populations between and within the main endemic regions of visceral leishmaniasis. Microbes Infect. 9334-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhls, K., I. L. Mauricio, F. Pratlong, W. Presber, and G. Schonian. 2005. Analysis of ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer sequences of the Leishmania donovani complex. Microbes Infect. 71224-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar, R., R. A. Bumb, N. A. Ansari, R. D. Mehta, and P. Salotra. 2007. Cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica in Bikaner, India: parasite identification and characterization using molecular and immunologic tools. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76896-901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis, J. R., and G. G. Koch. 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33159-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukes, J., I. L. Mauricio, G. Schonian, J. C. Dujardin, K. Soteriadou, J. P. Dedet, K. Kuhls, K. W. Tintaya, M. Jirku, E. Chocholova, C. Haralambous, F. Pratlong, M. Obornik, A. Horak, F. J. Ayala, and M. A. Miles. 2007. Evolutionary and geographical history of the Leishmania donovani complex with a revision of current taxonomy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1049375-9380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magill, A. J. 2005. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in the returning traveler. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 19241-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marfurt, J., I. Niederwieser, N. D. Makia, H. P. Beck, and I. Felger. 2003. Diagnostic genotyping of Old and New World Leishmania species by PCR-RFLP. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 46115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearson, R. D., and A. Q. Sousa. 1996. Clinical spectrum of leishmaniasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 221-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reithinger, R., and J. C. Dujardin. 2007. Molecular diagnosis of leishmaniasis: current status and future applications. J. Clin. Microbiol. 4521-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rioux, J. A., G. Lanotte, E. Serres, F. Pratlong, P. Bastien, and J. Perieres. 1990. Taxonomy of Leishmania. Use of isoenzymes. Suggestions for a new classification. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 65111-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schonian, G., A. Nasereddin, N. Dinse, C. Schweynoch, H. D. Schallig, W. Presber, and C. L. Jaffe. 2003. PCR diagnosis and characterization of Leishmania in local and imported clinical samples. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 47349-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strauss-Ayali, D., C. L. Jaffe, O. Burshtain, L. Gonen, and G. Baneth. 2004. Polymerase chain reaction using noninvasively obtained samples, for the detection of Leishmania infantum DNA in dogs. J. Infect. Dis. 1891729-1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Victoir, K., S. De Doncker, L. Cabrera, E. Alvarez, J. Arevalo, A. Llanos-Cuentas, D. Le Ray, and J. C. Dujardin. 2003. Direct identification of Leishmania species in biopsies from patients with American tegumentary leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 9780-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO. 2007, posting date. Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/burden/en/.

- 30.Zwart, G., E. J. van Hannen, M. P. Kamst-van Agterveld, K. Van der Gucht, E. S. Lindstrom, J. Van Wichelen, T. Lauridsen, B. C. Crump, S. K. Han, and S. Declerck. 2003. Rapid screening for freshwater bacterial groups by using reverse line blot hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 695875-5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]