Abstract

Heart valve (HV) culture is one of the major Duke criteria for the diagnosis of definite infectious endocarditis (IE). However, previous series suggest that heart valve culture does not have good sensitivity (7.8 to 17.6%) and may be contaminated during manipulation. Our goal was to establish the value of routine cultures of heart valves in patients with and without IE. From 2004 to 2006, resected heart valves were systematically cultured according to standard procedures. The definition and etiology of IE were based on the Duke criteria and on valve PCR of specimens from blood culture-negative patients. Bacterial and fungal broad-range PCR was performed. A total of 1,101 heart valves were studied: 1,030 (93.6%) from patients without IE and 71 (6.4%) from patients with IE (42 patients). Overall, 321 (29.2%) cultures were positive (28/71 [39.4%] IE cases and 293/1,030 [28.4%] non-IE). All IE patients with negative heart valve cultures had received antimicrobial therapy. The yield of culture of heart valves for IE diagnosis was as follows: sensitivity, 25.4%; specificity, 71.6%; positive predictive value (PPV), 5.8%; and negative predictive value, 93.3%. Because of its poor sensitivity and PPV, valve cultures should not be performed for patients without a clinical suspicion of IE. For patients with confirmed IE, heart valve cultures should be interpreted with caution.

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a relatively uncommon disease (1.7 to 6.2 cases/100,000 persons per year in Europe and the United States). However, it is extremely severe and has a mortality of 20 to 26% during initial hospital admission (5, 24, 28). Management can be optimized if an etiological diagnosis is made, but blood cultures are negative in 2.5 to 31% of patients (15, 22).

Heart surgery is necessary in 25 to 42% of patients with IE (5, 22, 27) and is usually performed when patients are already receiving antibiotics. IE is occasionally an unexpected finding during heart surgery performed for other indications (27).

A vegetation-positive culture is a major diagnostic criterion for IE (3, 24), although some authors have reported contaminant microorganisms growing in valve or endocardial tissue cultures (4, 13, 18). Some institutions recommend systematic culture of all surgically removed valve samples, but the value of this approach has not been sufficiently assessed or the criteria for assessment do not include clear clinical, microbiological, or molecular criteria (8-10).

The aim of our study was to analyze the value of systematic valve culture in a large series of patients with and without IE at a tertiary health care center.

(This study was presented in part at the 47th Annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Chicago, IL, 17 to 20 September, 2007.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective study was carried out from January 2004 to December 2006 in a tertiary reference center (1,750 beds) with a large heart surgery program. Surgical prophylaxis consisted of cefazolin or vancomycin in patients allergic to penicillin. Surgical prophylaxis was administered 30 to 60 min prior to incision. For procedures lasting more than 4 h, a second intraoperative dose was administered.

During the study period, heart surgeons were asked to submit to the microbiology laboratory all valve samples, with or without vegetations, from patients requiring valve replacement, regardless of the preoperative diagnosis. Patients were classified as having or not having IE; the modified Duke criteria were followed without taking into account the valve culture result (3). Demographic, clinical, diagnostic, and outcome data were collected according to a preestablished data entry sheet. All patients with endocarditis, especially patients with problematic diagnoses (negative blood cultures, dubious images in the echocardiography, etc.), were prospectively classified by the multidisciplinary endocarditis group (Group for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the Gregorio Marañón Hospital), which met regularly every 2 weeks. Cultures were classified as true/false positive/negative according to the results of blood culture, serology, and PCR. We systematically cultured all heart valves according to standard procedures. Valves were transported to the microbiology laboratory at the end of the operation in a sterile container. They were then divided under aseptic conditions in a laminar flow biological safety cabinet, and one part was transported to the pathology laboratory. Next, they were aseptically disrupted in a sterile mortar in the biological safety cabinet. Cultures were performed immediately after the valve tissue was ground on brain heart broth and on three types of agar media: Columbia sheep blood agar, chocolate agar supplemented with IsoVitaleX, and Brucella agar. Brain heart broth was incubated for up to 20 days, and a subculture of the broth was performed when turbidity was detected. Identification and susceptibility testing of the isolated bacteria were performed using Microscan panels (Dade Behring Inc., West Sacramento, CA) and conventional microbiological procedures.

A real-time broad-range 16S rRNA gene PCR followed by direct sequencing from heart valve tissue was performed on samples from all patients with heart valve surgery during the first 9 months (January 2004 to September 2004); from September 2004 to December 2006, PCR was performed only on samples from patients with a positive valve culture and/or clinical suspicion of IE. The methodology followed with the valve PCR has been previously reported by our group (20).

Three sets of aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures were obtained from all patients with fever or suspected IE. Blood was cultured using the Bactec 9240 system (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD), and bottles were incubated at 37°C for a maximum period of 20 days. Positive samples were characterized by Gram staining and subcultured on Columbia sheep blood agar, chocolate agar supplemented with IsoVitaleX, and Brucella agar before incubation for 5 days at 37°C in air, 5% CO2, and an anaerobic atmosphere, respectively. All microorganisms were identified following standard procedures.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of valve cultures were calculated using modified Duke criteria as the gold standard to define or rule out IE and the microorganisms isolated by blood culture and/or detected by PCR to establish an etiological diagnosis (3). A true-positive culture was defined as one in which the valve culture showed the etiological microorganism(s) in a patient with endocarditis. A false-positive culture was one in which a microorganism was recovered from a patient without endocarditis. A true-negative culture was when the valve culture from a patient without endocarditis was sterile, and a false-negative result was when the valve culture of a patient with endocarditis was sterile or yielded a contaminant microorganism in a patient with endocarditis that was different from the real cause of the endocarditis. These were not included as false positives since they belonged to patients with endocarditis. We used descriptive statistics to define the frequencies of microorganisms obtained from the valve culture. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for the diagnosis of endocarditis were assessed using the modified Duke criteria. These were calculated before and after surgery.

RESULTS

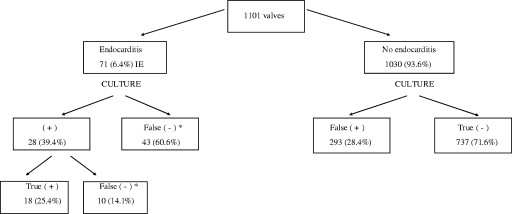

A total of 1,101 valves were studied: 71 (6.4%) from patients with IE and 1,030 (93.6%) from patients without IE (Fig. 1). The etiologies of the 42 IE episodes (71 valves) were established by a positive blood culture (37/42; 88.1%) and/or real-time broad-range 16S rRNA gene PCR of the valve tissue (34/37). The predominant causal microorganisms in our series were Streptococcus spp. (33.8% of the 71 valves), Staphylococcus aureus (23.9%), and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species (16.9%) (Table 1). The five patients with negative blood cultures (12 valves) had endocarditis caused by Tropheryma whipplei, Peptostreptococcus micros, Streptococcus gallolyticus, Candida albicans with coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, and S. gallolyticus. In these cases the diagnosis was provided by the PCR of the valve tissue.

FIG. 1.

Results of the culture of 1,101 valves from patients with and without IE. *, a valve culture was considered a false negative when the valve culture of a patient with endocarditis was sterile or yielded a contaminant microorganism.

TABLE 1.

Definitive etiology of the 71 valves from patients with IE

| Microorganism(s) | No. (%) of isolates | No. (%a) positive

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definite etiology

|

Positive valve cultures (n = 18)d | |||

| Blood cultures (n = 57)b | Positive PCR (n = 58)c | |||

| Gram-positive bacteria | ||||

| Streptococcus spp. | 24 (33.8)e | 17 (23.9) | 21 (29.6) | 5 (7.0) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 17 (23.9) | 17 (23.9) | 16 (22.5) | 5 (7.0) |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 12 (17)f | 12 (16.9) | 4 (5.6) | 3 (4.2) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 5 (7.0)g | 5 (7.0) | 4 (5.6) | 0 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) | 0 |

| Tropheryma whipplei | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 0 |

| Other | 2 (2.8)h | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | 0 |

| Gram-negative bacterium | ||||

| Neisseria sicca | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) | 0 |

| Fungi | ||||

| Candida albicans | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| Mixed | ||||

| C. albicans and coagulase-negative staphylococci | 5 (7.0) | 0 | 5 (7.0) | 4 (5.6) |

Percentages are expressed as number of positive samples of the 71 samples included.

Blood cultures were negative for five patients (12 valves).

PCR was performed on 61 valves and showed a false-negative result in three cases.

Only the 18 true-positive valve culture results are included in this table. The 10 discordant valve culture results are displayed in Table 2.

Streptococcus bovis, 6; S. gallolyticus, 6; S. mutans, 4; S. pyogenes, 3; S. acidominimus, 1; S. agalactiae, 1; S. gordoni, 1; S. mitis, 1; viridans group Streptococcus species, 1.

Staphylococcus epidermidis, 4; other coagulase-negative staphylococci, 8.

Enterococcus faecalis, 4; Enterococcus spp., 1.

Abiotrophia defectiva, 1; Peptostreptococcus micros, 1.

Culture of the 71 valves from patients with IE was positive in only 28 samples (39.4%), and of these only 18 (25.4%) were true positives. The remaining 43 cases had a negative valve culture (Fig. 1). All these patients were receiving antimicrobial therapy (100%), and in one case endocarditis was caused by a nonculturable microorganism (T. whipplei). Of the 28 positive valve cultures from patients with IE, culture showed a different microorganism from blood and valve PCR in 10 cases (35.7% of the 28 positive valve cultures and 14.1% from the 71 valves), which were classified as contaminants (positive predictive value of 5.8%). Blood cultures and real-time broad-range 16S rRNA gene PCR on valve tissue were concordant in all these problematic cases, which are detailed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Data on the 10 patients with IE who had a false-positive heart valve culture

| Case | Valve | Organism identified by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart valve culture | Blood culture | Valve PCR | ||

| 1 | Mitral, native | Enterococcus faecium | S. aureus | S. aureus |

| 2 | Aortic, native | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Streptococcus mutans | S. mutans |

| 3 | Aortic, native | S. aureus | S. mutans | S. mutans |

| 4 | Aortic, native | Coagulase-negative staphylococci | S. mutans | S. mutans |

| 5 | Mitral, native | Coagulase-negative staphylococci | E. faecalis | E. faecalis |

| 6 | Mitral, native | Coagulase-negative staphylococci | Negative | Streptococcus infantarius |

| 7 | Mitral, prosthetic | S. epidermidis | Listeria monocytogenes | L. monocytogenes |

| 8 | Aortic, native | Viridans group Streptococcus species | S. aureus | S. aureus |

| 9 | Aortic, prosthetic | S. epidermidis | S. aureus | S. aureus |

| 10 | Aortic, prosthetic | Propionibacterium acnes | S. aureus | S. aureus |

For patients without endocarditis, culture of the 1,030 valves was positive in 293 cases (false positives) (28.4%). The most commonly isolated microorganisms were S. epidermidis (52; 5%), other coagulase-negative staphylococci (49; 4.8%), other gram-positive microorganisms (45; 4.4%), and Enterococcus species (43; 4.2%) (Table 3). Blood cultures were obtained from all these patients and were always negative. Valve tissue was analyzed with PCR for 205 of the 293 valves with a false-positive culture and was negative for 200 and positive for 5. These five amplified between 28 and 31 cycles; they gave mixed, noninterpretable sequences and were considered PCR negative according to our standards. According to previous data from our group, for the diagnosis of IE the PCR result was considered a true positive when amplification was obtained before the 27th PCR cycle (19). An exhaustive review of the clinical records and evolution of these patients indicated that all the positive cultures were considered contaminants, and the five PCR-positive results were considered false positives.

TABLE 3.

Significance of all microorganisms isolated from the culture of 311 valves from patients without and with IE

| Microorganism(s) on valve culture | No. (%) of isolates

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients without IE (false positive) (n = 293) | Patients with IE (true positive) (n = 18) | Total (n = 311) | |

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 52 (100) | 0 | 52 |

| Other coagulase-negative staphylococci | 49 (94.2) | 3 (5.8) | 52 |

| Other gram-positive bacteria | 45 (100) | 0 | 45 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 43 (100) | 0 | 43 |

| Streptococcus spp. | 27 (84.4) | 5 (15.6) | 32 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 15 (75.0) | 5 (25.0) | 20 |

| Corynebacterium spp. | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 11 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | |||

| Gram-negative bacilli | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | 32 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 5 (100) | 0 | 5 |

| Eikenella corrodens | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Fungi | |||

| Candida spp. | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 9 |

| Aspergillus spp. | 4 (100) | 0 | 4 |

| Mixed | |||

| C. albicans with coagulase-negative staphylococci | 0 | 4 (100) | 4 |

Overall, 48.9% of microorganisms isolated from the 321 valves with a positive culture were recovered from broth medium only and the remaining 50.1% from both broth and solid media. Growth only in the broth medium provided 4/18 (22.2%) true-positive cultures (patients with endocarditis) but also 153/303 (50.5%) false-positive cultures, and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.03 by Fisher exact test).

Overall, heart valve culture showed a sensitivity of 25.4%, a specificity of 71.6%, a positive predictive value of 5.8%, and a negative predictive value of 93.3%.

DISCUSSION

According to our study, heart valves or endocardial material should not be routinely sent to the microbiology laboratory for culture. This applies both to patients without diagnostic criteria of IE and to patients with IE documented by blood cultures. For patients with no etiological diagnosis at the time of valve resection, valves should be cultured only under specific circumstances and results should be interpreted with caution, especially when microorganisms are recovered only from broth media. Our data, following precise criteria for interpretation, indicate that PCR of valve tissue is a much more reliable technique (12, 19, 20).

Recent changes in the epidemiology and etiology of IE mean that it is increasingly necessary to establish an accurate etiological diagnosis, since conventional susceptible pathogens are far less common. This is due to a higher proportion of nosocomial IE that affects debilitated patients and to the fact that many patients are treated with antimicrobial agents before an etiological diagnosis is made (29).

The etiology of endocarditis is generally determined using blood cultures, but 12% to 31% may have negative blood cultures (5, 10, 14, 16), mainly due to the use of antibiotics in the previous 2 weeks (22). Negative blood cultures may also be due to IE caused by fastidious or nonculturable microorganisms such as Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella species, Legionella species, Mycoplasma species, and Tropheryma whipplei.

When neither blood cultures nor serology is positive, the microbiological diagnosis relies on the valve tissue specimen, if available. IE requires surgical replacement of the affected valves in 25 to 42% of cases, thus providing the clinical microbiologist with an opportunity to establish the etiological diagnosis (5, 22, 27).

Culture of valve tissue with vegetations is one of the major diagnostic criteria for endocarditis. In this situation, a positive culture is considered a confirmation of endocardial infection and as such is recognized by the Duke criteria, although the very few studies addressing this issue in depth found frequent false-positive valve cultures (8, 9, 11, 23). It is important to note, however, that data on the specificity and positive predictive value of the valve culture are not provided in these studies. A more complete analysis was performed by Greub et al. (13) and by Bosshard et al. (4), although the number of patients was much smaller than in our series.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the largest series performed to date analyzing the value of culture of heart valves, from patients both with and without endocarditis, in a general hospital. We evaluated 1,101 valve specimens, 71 of which were from patients with IE. Our results demonstrate the low sensitivity (25.4%) and specificity (71.6%) of the technique. Moreover, valve culture alone did not establish the diagnosis in any of our patients with endocarditis. When patients without endocarditis are considered, 28.4% of valve cultures were (false) positive.

Previous antimicrobial therapy is the main reason for the very high rate of false-negative results in patients with endocarditis (85 to 87.5%) (25, 30). Morris et al. demonstrated that only 16% of the valves from patients who had received more than 25% of the standard antimicrobial therapy were culture positive at the time of surgery (23).

The explanation for the surprisingly high rate of contamination of valve cultures (7 to 17.7%) is more intriguing (11, 13, 17, 25). The possibility of latent IE was considered by Chuard et al., who reported 48 positive cultures in patients with no clinical suspicion of endocarditis, but a single unsuspected case of IE was disclosed by heart valve cultures over a 5-year period (9). Other possibilities include contamination in the operating room, during handling, or during laboratory processing. We homogenize most tissue samples with a sterile mortar following the recommended standard microbiological procedures. It may be argued that using a stomacher for homogenization of microbiological samples could be associated to a lower rate of contamination, although this has never been proven. In fact, Albon et al., using a stomacher, described a rate of contamination of 29% when culturing human corneas (1). As reported by other authors, a high proportion of the false-positive cultures in this study come from growth in thioglycolate or brain heart broth and not from agar plates (11). Atkins et al., using agar plates and broth, reported a similar high rate of contamination in cultures of normally sterile tissues obtained from noninfected patients during prosthetic joint surgery (2, 6). It is well known that liquid media can become positive in the presence of very small quantities of viable organisms. However, liquid medium is not the only explanation, since when using only agar plates, 34% of the cultures obtained at the end of 229 cardiovascular interventions were positive, although only seven patients developed postsurgical mediastinitis (2, 6).

Systematic heart valve culture is time-consuming and expensive and may have deleterious effects on the patient, to the extent that it can result in unnecessary overtreatment (8, 9). This overtreatment is understandable, since contaminated cultures usually yield microorganisms compatible with endocarditis, such as coagulase-negative staphylococci, viridans group Streptococcus species, Enterococcus species, and S. aureus and may be difficult for the surgeon not to treat when receiving the valve culture result (8, 11).

The introduction and validation of broad-range PCR to target commonly shared bacterial 16S rRNA genes and detect and differentiate bacteria in valve specimens have greatly improved the diagnosis of blood culture-negative endocarditis (12, 19, 20). Considering its sensitivity (41.2 to 96%) and specificity (95.3 to 100%) (4, 7, 13, 20), a positive heart valve tissue PCR is currently proposed by many authors to be a major criterion for the diagnosis of IE (19-21, 26). Furthermore, PCR may help in the clarification of unexpected or discordant valve culture results.

We have demonstrated that routine culture of heart valves must be avoided and that, even in patients with IE, their results should be interpreted with caution. We believe that the criterion of a positive bacteriology of vegetations that establishes a definite diagnosis of IE should be revised. Due to the cost and confounding nature of these cultures, firm statements against their use should be included in guidelines and procedures.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Thomas O'Boyle for his revision of the English in the manuscript.

This study was partially financed by the Programa de Centros de Investigación Biomédica en Red (CIBER) de Enfermedades Respiratorias CB06/06/0058, by Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) PI 061188, and by Fundación BBVA-Fundación Carolina for the research fellowship of Maricela Valerio.

This study does not present any conflicts of interest for the authors.

Members of the Group for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the Gregorio Marañón Hospital are E. Bouza, M. Desco, M. A. García-Fernández, M. Marín, M. Martínez-Selles, M. C. Menarguez, M. Moreno, P. Muñoz, B. Pinilla, A. Pinto, V. Ramallo, M. Rodríguez-Créixems, I. Tamallo, J. L. Vallejo, and F. Diaz.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albon, J., M. Armstrong, and A. B. Tullo. 2001. Bacterial contamination of human organ-cultured corneas. Cornea 20260-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkins, B. L., N. Athanasou, J. J. Deeks, D. W. Crook, H. Simpson, T. E. Peto, P. McLardy-Smith, A. R. Berendt, et al. 1998. Prospective evaluation of criteria for microbiological diagnosis of prosthetic-joint infection at revision arthroplasty. J. Clin. Microbiol. 362932-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baddour, L. M., W. R. Wilson, A. S. Bayer, V. G. Fowler, Jr., A. F. Bolger, M. E. Levison, P. Ferrieri, M. A. Gerber, L. Y. Tani, M. H. Gewitz, D. C. Tong, J. M. Steckelberg, R. S. Baltimore, S. T. Shulman, J. C. Burns, D. A. Falace, J. W. Newburger, T. J. Pallasch, M. Takahashi, and K. A. Taubert. 2005. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation 111e394-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosshard, P. P., A. Kronenberg, R. Zbinden, C. Ruef, E. C. Bottger, and M. Altwegg. 2003. Etiologic diagnosis of infective endocarditis by broad-range polymerase chain reaction: a 3-year experience. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouza, E., A. Menasalvas, P. Muñoz, F. J. Vasallo, M. del Mar Moreno, and M. A. Garcia Fernandez. 2001. Infective endocarditis—a prospective study at the end of the twentieth century: new predisposing conditions, new etiologic agents, and still a high mortality. Medicine (Baltimore) 80298-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouza, E., P. Muñoz, L. Alcala, M. J. Perez, C. Rincon, J. M. Barrio, and A. Pinto. 2006. Cultures of sternal wound and mediastinum taken at the end of heart surgery do not predict postsurgical mediastinitis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 56345-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitkopf, C., D. Hammel, H. H. Scheld, G. Peters, and K. Becker. 2005. Impact of a molecular approach to improve the microbiological diagnosis of infective heart valve endocarditis. Circulation 1111415-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell, W. N., W. Tsai, and L. A. Mispireta. 2000. Evaluation of the practice of routine culturing of native valves during valve replacement surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 69548-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuard, C., C. M. Antley, and L. B. Reller. 1998. Clinical utility of cardiac valve Gram stain and culture in patients undergoing native valve replacement. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 122412-415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Salvo, G., F. Thuny, V. Rosenberg, V. Pergola, O. Belliard, G. Derumeaux, A. Cohen, D. Iarussi, R. Giorgi, J. P. Casalta, P. Caso, and G. Habib. 2003. Endocarditis in the elderly: clinical, echocardiographic, and prognostic features. Eur. Heart J. 241576-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giladi, M., O. Szold, A. Elami, D. Bruckner, and B. L. Johnson, Jr. 1997. Microbiological cultures of heart valves and valve tags are not valuable for patients without infective endocarditis who are undergoing valve replacement. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24884-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldenberger, D., A. Kunzli, P. Vogt, R. Zbinden, and M. Altwegg. 1997. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis by broad-range PCR amplification and direct sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 352733-2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greub, G., H. Lepidi, C. Rovery, J. P. Casalta, G. Habib, F. Collard, P. E. Fournier, and D. Raoult. 2005. Diagnosis of infectious endocarditis in patients undergoing valve surgery. Am. J. Med. 118230-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoen, B., C. Selton-Suty, F. Lacassin, J. Etienne, S. Briancon, C. Leport, and P. Canton. 1995. Infective endocarditis in patients with negative blood cultures: analysis of 88 cases from a one-year nationwide survey in France. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20501-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houpikian, P., and D. Raoult. 2005. Blood culture-negative endocarditis in a reference center: etiologic diagnosis of 348 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 84162-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamas, C. C., and S. J. Eykyn. 2003. Blood culture negative endocarditis: analysis of 63 cases presenting over 25 years. Heart 89258-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang, S., R. W. Watkin, P. A. Lambert, R. S. Bonser, W. A. Littler, and T. S. Elliott. 2004. Evaluation of PCR in the molecular diagnosis of endocarditis. J. Infect. 48269-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang, S., R. W. Watkin, P. A. Lambert, W. A. Littler, and T. S. Elliott. 2004. Detection of bacterial DNA in cardiac vegetations by PCR after the completion of antimicrobial treatment for endocarditis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10579-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lisby, G., E. Gutschik, and D. T. Durack. 2002. Molecular methods for diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 16393-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marin, M., P. Muñoz, M. Sanchez, M. Del Rosal, L. Alcala, M. Rodriguez-Creixems, and E. Bouza. 2007. Molecular diagnosis of infective endocarditis by real time broad-range polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing directly from heart valve tissue. Medicine (Baltimore) 86195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millar, B., J. Moore, P. Mallon, J. Xu, M. Crowe, R. McClurg, D. Raoult, J. Earle, R. Hone, and P. Murphy. 2001. Molecular diagnosis of infective endocarditis—a new Duke's criterion. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 33673-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreillon, P., and Y. A. Que. 2004. Infective endocarditis. Lancet 363139-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris, A. J., D. Drinkovic, S. Pottumarthy, M. G. Strickett, D. MacCulloch, N. Lambie, and A. R. Kerr. 2003. Gram stain, culture, and histopathological examination findings for heart valves removed because of infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36697-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prendergast, B. D. 2004. Diagnostic criteria and problems in infective endocarditis. Heart 90611-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renzulli, A., A. Carozza, C. Marra, G. P. Romano, G. Ismeno, M. De Feo, A. Della Corte, and M. Cotrufo. 2000. Are blood and valve cultures predictive for long-term outcome following surgery for infective endocarditis? Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 17228-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rice, P. A., and G. E. Madico. 2005. Polymerase chain reaction to diagnose infective endocarditis: will it replace blood cultures? Circulation 1111352-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shapira, N., O. Merin, E. Rosenmann, I. Dzigivker, D. Bitran, A. M. Yinnon, and S. Silberman. 2004. Latent infective endocarditis: epidemiology and clinical characteristics of patients with unsuspected endocarditis detected after elective valve replacement. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 781623-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace, S. M., B. I. Walton, R. K. Kharbanda, R. Hardy, A. P. Wilson, and R. H. Swanton. 2002. Mortality from infective endocarditis: clinical predictors of outcome. Heart 8853-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, A., E. Athan, P. A. Pappas, V. G. Fowler, Jr., L. Olaison, C. Pare, B. Almirante, P. Muñoz, M. Rizzi, C. Naber, M. Logar, P. Tattevin, D. L. Iarussi, C. Selton-Suty, S. B. Jones, J. Casabe, A. Morris, G. R. Corey, and C. H. Cabell. 2007. Contemporary clinical profile and outcome of prosthetic valve endocarditis. JAMA 2971354-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watkin, R. W., S. Lang, P. A. Lambert, W. A. Littler, and T. S. Elliott. 2003. The microbial diagnosis of infective endocarditis. J. Infect. 471-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]