Abstract

Glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (GISA) and, in particular, heterogeneous GISA (hGISA) are difficult to detect by standard MIC methods, and thus, an accurate detection method for clinical practice and surveillances is needed. Two prototype Etest strips designed for hGISA/GISA resistance detection (GRD) were evaluated using a worldwide collection of hGISA/GISA strains covering the five major clonal lineages. A total of 150 strains comprising 15 GISA and 60 hGISA strains (defined by population analysis profiles-area under the curve [PAP-AUC]), 70 glycopeptide-susceptible S. aureus (GSSA) strains, and 5 S. aureus ATCC reference strains were tested. For standardized Etest vancomycin (VA) MIC testing, the modified Etest macromethod with VA and teicoplanin (TP) strips tested with a heavier inoculum using brain heart infusion agar (BHI) and two glycopeptide screening agar plates (6 μg/ml VA/BHI and 5 μg/ml Mueller-Hinton agar [MHA]) were tested in parallel with the two new Etest GRD strips: a VA 32 (0.5-μg/ml)-TP 32 (0.5-μg/ml) double-sided gradient (E-VA/TP) with one prototype overlaid with a nutrient (E-VA/TP+S) to enhance the growth of hGISA. The Etest GRD strips were tested with a standard 0.5-McFarland standard inoculum using MHA and MHA plus 5% blood (MHB) and were read at 18 to 24 and 48 h. The interpretive MIC cutoffs used for the new Etest GRD strips at 24 and 48 h were as follows: for GISA, TP or VA, ≥8, and a standard VA MIC of ≥6; for hGISA, TP or VA, ≥8, and a standard VA MIC of ≤4. The results on MHB at 48 h showed that E-VA/TP+S had high specificity (94%) and sensitivity (95%) in comparison to PAP-AUC and was able to detect all GISA (n = 15) and 98% of hGISA (n = 60) strains. In contrast, the glycopeptide screening plates performed poorly for hGISA. The new Etest GRD strip (E-VA/TP+S), utilizing standard media and inocula, is a simple and acceptable tool for detection of hGISA/GISA for clinical and epidemiologic purposes.

The first reports of glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (GISA) strains raised some complex and challenging questions with respect to their clinical significance, methods for the detection of these phenotypes, and the definition of this “resistance,” all issues that persist today (10, 23). Additionally, a heterogeneous form of the resistance (heterogeneous GISA [hGISA]) is frequently seen in which only a small proportion of the population (approximately 10−6) expresses the resistant phenotype, creating even further detection dilemmas (10). It took over 10 years for heterogeneous methicillin-resistant S. aureus (hMRSA) to be considered the same phenotype (and genotype) as MRSA, and this may prove to be the case for hGISA, as well (4).

hGISA and GISA have been the subjects of many recent reviews covering their mechanisms of resistance, clinical relevance, treatment challenges, and detection methods (3, 7, 9, 15, 19, 20, 22, 23). It now appears that hGISA and GISA have common structural and clinical features, leading many researchers to feel that they are almost identical and should be reported as such (12). Generally speaking, both hGISA and GISA possess thickened cell walls, are associated with prolonged glycopeptide therapy and low glycopeptide serum concentrations, and often share a number of genetic expression markers, e.g., atl and mrpB (8, 15, 18, 27, 28, 30). More importantly, there are an increasing number of studies alluding to the clinical significance of hGISA and its association with vancomycin (VA) failures (5, 13, 14, 27).

The current differentiation of hGISA from GISA appears to imply that GISA possesses a homogeneously VA-resistant population, in contrast to hGISA. However, population studies of strains with reduced susceptibility to VA (MICs, 2 to 16 μg/ml) have shown that this is indeed not the case and that GISA strains often present with a nonhomogeneous or heterogeneous VA kill curve. The obvious difference seen between hGISA and GISA is that the GISA isolates more often produce enough of the subpopulation expressing the intermediate level of “resistance” that the cells will grow on VA at 4 μg/ml when tested with standard inoculum equivalent to 0.5 McFarland standard. Accordingly, there is much debate over whether the current CLSI VA-intermediate breakpoint of 4 to 8 μg/ml is appropriate for detecting all hGISA/GISA phenotypes. A recent study in which VA MICs for 20 GISA, 157 hGISA, and 106 non-GISA isolates were determined indicated that the current intermediate breakpoint of 4 μg/ml should be reduced to 2 μg/ml to better identify the hGISA/GISA strains (31). This notion is further supported by the CDC, which has revised its S. aureus/VA algorithm, accommodating VA-intermediate S. aureus stains that do not express high levels of VA resistance (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/ar_visavrsa.html). This initiative was adopted by the CLSI in 2005, and appropriate amendments were subsequently made to Tables 2C, M2, and M7 on their website (http://www.clsi.org).

TABLE 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of E-VA/TP+/-S on MHA and MHB, and E-M for detection of hGISA/GISA phenotypes characterized by PAP-AUC

| Test | Medium | Time of reading (h) | Detection (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |||

| Etest GRD strips | ||||

| E-VA/TP | MHA | 24 | 53 | 100 |

| 48 | 80 | 95 | ||

| MHB | 24 | 55 | 100 | |

| 48 | 89 | 95 | ||

| E-VA/TP+S | MHA | 24 | 63 | 100 |

| 48 | 84 | 95 | ||

| MHB | 24 | 70 | 100 | |

| 48 | 94 | 95 | ||

| E-M | BHI/2 McFarland | 24 | 80 | 87 |

| 48 | 94 | 96 | ||

| Agar screens | VA/BHI | 48 | 27 | 100 |

| TP/MH | 48 | 65 | 95 | |

Since their advent nearly 10 years ago, many methods have been advocated for detecting hGISA/GISA (6). Automated methods have been modified to try to detect high-level VA-resistant S. aureus (MIC > 32 μg/ml); however, these methods struggle to detect GISA and are inappropriate for detecting hGISA (1, 2). As disk diffusion testing was quickly recognized to be unsuitable (16), other methods have been proposed, such as glycopeptide screening plates (6) and various population studies (11, 29). Other techniques, such as the modified Etest method (macromethod [E-M]), have also been introduced, but E-M requires nonstandard media (brain heart infusion [BHI]) and 2.0-McFarland standard inoculum, i.e., variations that are beyond the standard susceptibility-testing praxis (26). Accordingly, we investigated a new Etest hGISA/GISA resistance detection (GRD) strip (E-VA/teicoplanin [TP]), one with a growth nutrient incorporated into the strip (E-VA/TP+S) and one without. The GRD strip uses a standard inoculum and agar, and in this study, we tested it against an international collection of hGISA/GISA/non-GISA strains comprising different multilocus sequence-typing profiles and established genetic lineages (17).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The following reference organisms were used and were tested in quintuplicate: S. aureus ATCC 29213 and 25923 (non-MRSA), ATCC 43300 (MRSA), ATCC 700698 (Mu3; hGISA), and ATCC 700699 (Mu50; GISA). The clinically derived test strains comprised the following: 15 GISA, 60 hGISA (defined by a positive population analysis profile-area under the curve [PAP-AUC]), and 70 glycopeptide-susceptible S. aureus (GSSA) strains. These isolates comprised an international collection of unique strains (different clones) including all five major endemic MRSA clonal lineages (17).

Media and antibiotics.

BHI and Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) were obtained from BBL (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD). VA and TP antibiotic powders were obtained from Fagron (Barsbuttel, Germany) and Molcan Corp. (Richmond Hill, Canada), respectively.

E-M.

E-M was performed as described by Walsh et al. (26). A suspension of colonies from an overnight culture on a blood plate was prepared in Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth, and the turbidity was adjusted to 2.0 McFarland standard, after which 200 μl of the suspension was pipetted and evenly streaked out on the surface of a 90-mm BHI agar plate. The Etest standard procedure for MIC testing of VA was performed using an inoculum suspension in 0.9% saline (0.5 McFarland standard) that was streaked onto MHA plates (BBL). After the plates were dried for approximately 10 min, Etest strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) for VA (0.016 to 256 μg/ml) and TP (0.016 to 256 μg/ml) were applied to the BHI plate and VA was applied to the MH plate. The agar plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 to 24 and 48 h and were read by two different laboratory technicians.

Etest GRD strip.

The two new Etest prototype strips evaluated were a VA 32-0.5-μg/ml-TP 32-0.5-μg/ml double-sided gradient (E-VA/TP), with one prototype having a nutrient incorporated into the strip (E-VA/TP+S) to enhance the growth of hGISA. Both strips were tested with standard inoculum (0.5 McFarland standard) using MHA (BBL) ± 5% blood (MHB) and read at 18 to 24 and 48 h. The endpoints read from the Etest GRD strips should not be regarded as true MICs, but rather as modified results with interpretive cutoffs defined for the phenotypic detection of glycopeptide resistance phenotypes in S. aureus. The preliminary interpretive cutoffs used for the Etest GRD prototype strips read at 24 and 48 h were as follows: GISA, E-M values for TP or VA of ≥8 and a standard VA MIC of ≥6; hGISA, E-M values for TP or VA of ≥8 and a standard VA MIC of ≤4.

VA screening plate.

The VA (6 μg/ml) BHI screening plate (21, 24, 26) recommended by the CDC (http://www.cdc.gov) was used. All plates were spot inoculated with 10 μl of an inoculum suspension prepared with growth from an overnight blood agar plate, with a turbidity equivalent to 0.5 McFarland standard. The plates were incubated for 48 h, and growth was reported after both 24 and 48 h.

TP screening plate.

The TP (5 μg/ml) MHA screening plate recommended by the Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie (CA-SFM) (http://www.sfm.asso.fr) was used. All plates were spot inoculated with 10 μl of an inoculum suspension prepared with growth from an overnight blood agar plate, with a turbidity equivalent to 2 McFarland standard. The plates were incubated for 48 h, and growth was reported after both 24 and 48 h.

PAP-AUC.

The method described by Wootton et al. was used (29) for PAP-AUC. After 24 h of incubation in tryptone soya broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom), an undiluted culture and dilutions of 1/108 and 1/105 were inoculated, using a spiral plater (Don Whitley, Shipley, United Kingdom), onto BHI agar (Oxoid) plates containing 0.5, 1, 2.5, 4, and 8 μg/ml of VA. Colonies were counted after 48 h of incubation. The number of CFU/ml was plotted against the VA concentration using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA). The AUC was plotted for each test strain and compared with the curves for Mu3, Mu50, and S. aureus ATCC control strains. A ratio was then calculated by dividing the AUC of the test strain by the AUC of Mu3. The isolates used had their PAP-AUCs calculated prior to commencement of the study; however, a random sample (50 isolates) was chosen to ensure that the PAP-AUC value, i.e., the hGISA/GISA phenotype, had been maintained.

Statistical analysis.

The performance of each method in detecting hGISA/GISA was evaluated by comparison with the PAP-AUC ratio. Each method was assessed for its specificity and sensitivity in discriminating hGISA/GISA from GSSA, as previously described (26). The specificity was based on the number of correct negative results, i.e., the true number of GSSA strains that were correctly identified. The sensitivity was based on the number of hGISA/GISA strains that were correctly identified.

RESULTS

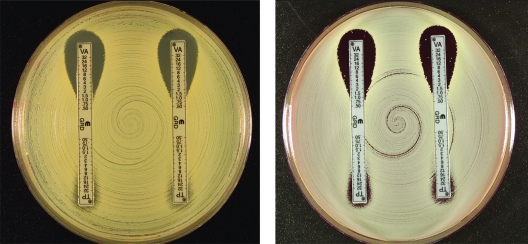

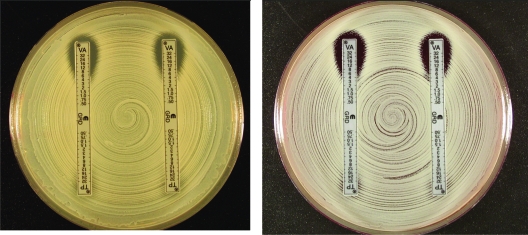

Figures 1 to 3 show examples of results with the new Etest VA/TP+S strips for S. aureus ATCC 29213, ATCC 700698 (Mu3), and ATCC 700699 (Mu50), respectively. Table 1 shows the MIC range for each of the methods. Typically, the GRD values for the negative control GSSA strain, S. aureus ATCC 29213, for VA and TP varied between 0.5 and 1 μg/ml on both MHA and MHB. For hGISA and GISA, the MIC ranges were higher after 48 h, and the resistance was enhanced by the presence of both the blood and the growth supplement (Table 1). S. aureus ATCC 700698 (Mu3) gave low VA values and discernibly high TP values (≥32 μg/ml), and small-colony variants (SCVs) were clearly visible within the TP inhibition ellipses on MHA and MHB. S. aureus ATCC 700699 (Mu50) gave high VA values (12 μg/ml) compared to Mu3, with SCVs clearly visible in the VA inhibition ellipse, particularly on MHB. Predictably, the Mu50 GISA phenotype had a very high TP value (>32 μg/ml) and almost no inhibition ellipse.

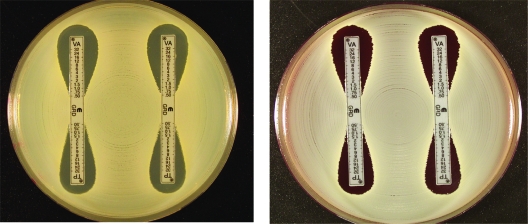

FIG. 1.

E-VA/TP and E-VA/TP+S with MHA and MHB for S. aureus ATCC 29213. (Left panel) MHA, E-VA/TP (left) and E-VA/TP+S (right). (Right panel) MHB.

FIG. 2.

E-VA/TP and E-VA/TP+S with MHA (left) and MHB (right) for S. aureus ATCC 700698 (Mu3; hGISA).

FIG. 3.

E-VA/TP and E-VA/TP+S with MHA (left) and MHB (right) for S. aureus ATCC 700699 (Mu50/GISA).

TABLE 1.

MIC ranges for GRD Etest and standard MICs compared with the Etest macro-method and PAP-AUC

| Phenotype | MIC range at indicated time (h)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRD MHAa

|

GRD MHBb

|

GRD + S MHAc

|

GRD + S MHBd

|

E-M

|

PAP-AUC | VAe | TPe | ||||||||||||||||

| VA

|

TP

|

VA

|

TP

|

VA

|

TP

|

VA

|

TP

|

VA

|

TP

|

||||||||||||||

| 24g | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | ||||

| MSSAf | 0.5-0.75 | 0.75-1.5 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.5-2.0 | 0.5-0.75 | 0.75-1.5 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.75-1.5 | 0.5-1.5 | 0.5-2.0 | 0.75-1.0 | 0.75-2.0 | 0.5-0.75 | 0.75-1.5 | 0.75-1.5 | 1.0-3 | 2-3 | 2-4 | 1.5-3 | 2-6 | 0.32-0.84 | 0.25-1 | 1-2 |

| MRSA | 0.5-0.75 | 0.75-1.0 | 0.5-1.0 | 1.5-2 | 0.75-1.0 | 1.0-1.5 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.75-1.5 | 0.5-0.75 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.5-2.0 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.75-1.5 | 0.75-1.5 | 1.0-3.0 | 1.5-3 | 1.5-3 | 2-4 | 1.5-4 | 0.48-0.86 | 0.5- 1 | 1.5-2 |

| hGISA | 0.75-1.0 | 1-4 | 1-8 | 2-32 | 0.75-2 | 0.75-12 | 1.5-32 | 2-32 | 0.75-2 | 1-8 | 2-12 | 4-24 | 1-8 | 2-16 | 2-32 | 6-32 | 3-12 | 3-12 | 1.5-12 | 12-32 | 0.91-1.25 | 1.5- 6 | 1- 12 |

| GISA | 6-12 | 6-12 | 32->32 | >32 | 6-12 | 12-16 | 16-32 | 32->32 | 8-12 | 24-32 | 16-32 | 32->32 | 8-16 | 16-24 | 16->32 | >32 | 4-16 | 8-32 | 12-24 | 16-32 | 1.08-1.55 | 4-8 | 4-16 |

GRD with MHA.

GRD with MHB.

GRD plus supplements with MHA.

GRD plus supplements with MHB.

MICs were read at 18 h.

MSSA, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus.

After 24 or 48 h.

Table 2 compares the sensitivity and specificity of the Etest GRD strips (E-VA/TP ± S) with the E-M for the 150 PAP-AUC phenotypically characterized strains. For the detection of hGISA/GISA, the E-VA/TP+S strip tested on MHB and read at 48 h had the highest sensitivity (94%) and was comparable to the E-M. The addition of 5% blood to MHA (MHB) increased the 48-h detection sensitivity for E-VA/TP and E-VA/TP+S from 80 to 89% and from 84 to 94%, respectively. The sensitivity for the 24-h reading was appreciably lower than that for 48 h, confirming the need for extended incubation to optimize the detection of glycopeptide resistance. After 48 h of incubation, all methods gave a specificity of 95 to 96%.

The VA screening plate, VA/BHI, missed most hGISA/GISA strains (overall sensitivity, 27%) (Table 2), with 12% sensitivity for hGISA and 87% sensitivity for GISA. The CA-SFM screening plate (TP/MHA) was better than VA/BHI, with an overall sensitivity of 65% and a specificity of 95%. However, while it was able to detect most GISA strains (93% sensitivity), it had a sensitivity of only 58% for hGISA strains.

All strains were independently tested in triplicate under blind conditions to examine the robustness of each method. Table 3 summarizes the reproducibility of the Etest GRD strips (E-VA/TP and E-VA/TP+S) and E-M to the two agar screening plates. For the GISA strains (n = 15), the E-VA/TP and E-VA-TP+S strips and E-M had 100% reproducibility compared to the agar screens, VA/BHI and TP/MHA, which had 87 and 93%, respectively. The screening plates were unreliable for the detection of hGISA (n = 60), with VA/BHI and TP/MHA having poor reproducibilities of 12% and 58%, respectively. The best performance for the repeated detection of hGISA was found with the E-VA/TP+S strip on MHB, which had a reproducibility of 98% at 48 h. The addition of blood to MHA proved very effective in increasing the reproducibility of hGISA detection from 81 to 95% and from 89 to 98% for the E-VA/TP and EVA/TP+S strips, respectively (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Reproducibility of Etest GRD, E-M, and agar screening for detection of hGISA/GISA/GSSA

| Strain(s)a | % Correct phenotype

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etest GRD (48 h)

|

E-M (BHI/2 McFarland) | Agar screen

|

|||||

| E-VA/TP

|

E-VA/TP+S

|

||||||

| MH | MHB | MH | MHB | VA/BHI | TP/MH | ||

| GISA | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 87 | 93 |

| hGISA | 81 | 95 | 89 | 98 | 92 | 12 | 58 |

| 5 ATCC strains | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 |

For GISA, 15 isolates were tested in triplicate; for hGISA, 60 isolates were tested in triplicate; and for the five ATCC reference strains, 25 isolates were tested in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

The increasing debate over the clinical significance of GISA, and in particular hGISA, has been compounded by the difficulty of detecting them. The clinical failure attributable to glycopeptide use may in part be due to their physical and chemical properties, high protein binding, and potentially insufficient drug levels at the infection site due to poor pharmacokinetics properties of the drug and difficulties in optimizing the dose and dosing regimen relative to concentration-related toxicities of the drugs (25). However, despite subtherapeutic drug levels, it is now known that staphylococci can respond to the presence of low levels of glycopeptide, which can subsequently select for low-level resistance. This type of heterogeneous and variable resistance in staphylococci, which is expressed at various frequencies within the population, is not detectable by either disk diffusion (16, 27) or automated susceptibility testing systems (8, 24), a phenomenon recognized by numerous expert groups, including the CDC (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/ar_visavrsa.html), CLSI (http://www.clsi.org), the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (http://www.bsac.org.uk), and CA-SFM (http://www.sfm.asso.fr). To address the limitations of disk diffusion and automated systems, agar screening plates have been developed as simple alternatives to screen for hGISA/GISA strains, since PAP methods are highly specialized and unsuitable for use in clinical laboratories. The PAP-AUC used as the reference method in this study, while labor-intensive, is sensitive. The VA/BHI plate, initially developed for VA resistance screening of enterococci, is commercially available and is widely used in the United States. However, this study and various others have clearly shown that this method is poor at detecting hGISA and occasionally fails to detect GISA strains. TP, a more sensitive marker for the detection of hGISA/GISA, is not available as a commercial reagent in the United States, thus precluding the TP/MHA plate as a viable option for screening of hGISA/GISA.

The E-M was first introduced as a potential screening method for detecting hGISA/GISA and thereafter was further investigated in a controlled study (26). The new Etest GRD strip with double-sided VA and TP concentration gradients across seven dilutions (E-VA/TP) was designed to be used with normal media and at a standard inoculum, circumventing some of the perceived problems that arose with the macromethod. GISA and hGISA strains are notoriously slow growing, and their standard features are a thickened cell wall and a pleomorphic appearance, often involving SCVs. Accordingly, in order to detect all SCVs, a growth supplement that enhances their growth and thus their detection has been added. The two prototypes (E-VA/TP and E-VA/TP+S) were examined using the standard inoculum of 0.5 McFarland standard on two different agar plates (MHA and MHB) that are readily available in the clinical laboratory. The sensitivity at 48 h is greater than that at 24 h (Table 2), as the SCVs are large enough to be seen with the naked eye and are visible as a light growth within the Etest ellipse (Fig. 1 to 3). Given that VA is often used for an extended period (some studies report hGISA being treated for a period of 18 weeks), we feel that the 48-h incubation period for improved sensitivity is appropriate and does not overtly affect the clinical outcome (27). Results for E-VA/TP+S read after 18 to 24 h of incubation, if positive for hGISA/GISA, can be reported as such, although negative results should be confirmed after 48 h of incubation, since sensitivity was highest at 48 h, detecting all GISA (n = 15) and 98% of hGISA (n = 60) strains on MHB.

Clinicians and laboratories alike are becoming increasingly aware that patients on long-term VA therapy and cases of recurrent MRSA bacteremia (5, 12) may signal the presence and potential spread of hGISA/GISA strains. The extent of the problem is still unknown, as laboratories are not equipped with appropriate and sensitive test methods that can reliably detect these phenotypes in their clinical routines. Here, we have presented a new method, the Etest GRD strip with VA and TP, that performs as well as the E-M and the reference PAP-AUC assay but with the simplicity of a standard routine diagnostic test that can be used daily for clinical and epidemiological purposes.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. 2004. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—New York, 2004. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 53322-323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 2002. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—Pennsylvania, 2002. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appelbaum, P. C. 2006. The emergence of vancomycin-intermediate and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12(Suppl. 1)16-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger-Bachi, B. 2002. Resistance mechanisms of gram-positive bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 29227-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charles, P. G., P. B. Ward, P. D. Johnson, B. P. Howden, and M. L. Grayson. 2004. Clinical features associated with bacteremia due to heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38448-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosgrove, S. E., K. C. Carroll, and T. M. Perl. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39539-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fridkin, S. K. 2001. Vancomycin-intermediate and -resistant Staphylococcus aureus: what the infectious disease specialist needs to know. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32108-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fridkin, S. K., J. Hageman, L. K. McDougal, J. Mohammed, W. R. Jarvis, T. M. Perl, and F. C. Tenover. 2003. Epidemiological and microbiological characterization of infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin, United States, 1997-2001. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36429-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiramatsu, K. 2001. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a new model of antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 1147-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiramatsu, K., L. Cui, M. Kuroda, and T. Ito. 2001. The emergence and evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 9486-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiramatsu, K., H. Hanaki, T. Ino, K. Yabuta, T. Oguri, and F. C. Tenover. 1997. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40135-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howden, B. P. 2005. Recognition and management of infections caused by vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) and heterogenous VISA (hVISA). Intern. Med. J. 35(Suppl. 2)S136-S140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howden, B. P., P. G. Charles, P. D. Johnson, P. B. Ward, and M. L. Grayson. 2005. Improved outcomes with linezolid for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: better drug or reduced vancomycin susceptibility? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 494816. (Author's reply, 49:4816-4817.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howden, B. P., P. D. Johnson, P. G. Charles, and M. L. Grayson. 2004. Failure of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 391544. (Author's reply, 39:1544-1545.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howden, B. P., P. B. Ward, P. D. Johnson, P. G. Charles, and M. L. Grayson. 2005. Low-level vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus—an Australian perspective. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24100-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howe, R. A., K. E. Bowker, T. R. Walsh, T. G. Feest, and A. P. MacGowan. 1998. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 351602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howe, R. A., A. Monk, M. Wootton, T. R. Walsh, and M. C. Enright. 2004. Vancomycin susceptibility within methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10855-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howe, R. A., M. Wootton, T. R. Walsh, P. M. Bennett, and A. P. Macgowan. 2000. Heterogeneous resistance to vancomycin in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45130-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeltz, R. F., and B. J. Wilkinson. 2004. The escalating challenge of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 4273-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tenover, F. C. 1999. Implications of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Hosp. Infect. 43(Suppl.)S3-S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tenover, F. C., J. W. Biddle, and M. V. Lancaster. 2001. Increasing resistance to vancomycin and other glycopeptides in Staphylococcus aureus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7327-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenover, F. C., M. V. Lancaster, B. C. Hill, C. D. Steward, S. A. Stocker, G. A. Hancock, C. M. O'Hara, S. K. McAllister, N. C. Clark, and K. Hiramatsu. 1998. Characterization of staphylococci with reduced susceptibilities to vancomycin and other glycopeptides. J. Clin. Microbiol. 361020-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tenover, F. C., and L. C. McDonald. 2005. Vancomycin-resistant staphylococci and enterococci: epidemiology and control. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18300-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tenover, F. C., M. J. Mohammed, J. Stelling, T. O'Brien, and R. Williams. 2001. Ability of laboratories to detect emerging antimicrobial resistance: proficiency testing and quality control results from the World Health Organization's external quality assurance system for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39241-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turnidge, J., and M. L. Grayson. 1993. Optimum treatment of staphylococcal infections. Drugs 45353-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh, T. R., A. Bolmstrom, A. Qwarnstrom, P. Ho, M. Wootton, R. A. Howe, A. P. MacGowan, and D. Diekema. 2001. Evaluation of current methods for detection of staphylococci with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides. J. Clin. Microbiol. 392439-2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh, T. R., and R. A. Howe. 2002. The prevalence and mechanisms of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56657-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wootton, M., P. M. Bennett, A. P. MacGowan, and T. R. Walsh. 2005. Reduced expression of the atl autolysin gene and susceptibility to autolysis in clinical heterogeneous glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hGISA) and GISA strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56944-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wootton, M., R. A. Howe, R. Hillman, T. R. Walsh, P. M. Bennett, and A. P. MacGowan. 2001. A modified population analysis profile (PAP) method to detect hetero-resistance to vancomycin in Staphylococcus aureus in a UK hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47399-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wootton, M., A. P. Macgowan, and T. R. Walsh. 2005. Expression of tcaA and mprF and glycopeptide resistance in clinical glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (GISA) and hetero-resistant GISA strains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1726326-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wootton, M., T. R. Walsh, and A. P. MacGowan. 2005. Evidence for reduction in breakpoints used to determine vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 493982-3983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]